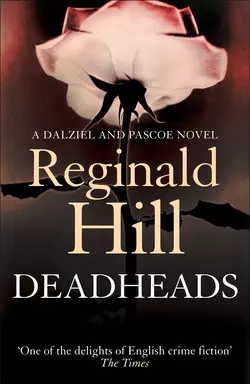

Deadheads

Reginald Hill

‘Humour and topicality along a cold enigmatic trail of murder’ ObserverLife is on the up for Patrick Aldermann: his Great Aunt Florence has collapsed into her rose bed leaving him Rosemont House with its splendid gardens.But when his boss, ‘Dandy’ Dick Elgood, suggests to Peter Pascoe that Aldermann is a murderer – then later retracts the accusation – the detective inspector is left with a thorny problem.Not only have the police already dug up some interesting information about Aldermann’s beautiful wife; it also appears that his rapid promotion has been helped by the convenient deaths of some of his colleagues…

REGINALD HILL

DEADHEADS

A Dalziel and Pascoe novel

Copyright (#ulink_d7ea4fe6-fed0-5ba5-becb-5b1910e5855b)

Harper An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1983

Copyright © Reginald Hill 1983

Reginald Hill asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source: 9780586072523

Ebook Edition © July 2015 ISBN: 9780007370290

Version 2015-06-22

‘There is a splendid kind of indolence, where a man, having taken an aversion to the wearisomeness of a business which properly belongs to him, neglects not, however, to employ his thoughts, when they are vacant from what they ought more chiefly to be about, in other matters not entirely unprofitable to life, the exercise of which he finds he can follow with more abundant ease and satisfaction.’

DEFOE: The Life and Adventures ofMr Duncan Campbell

‘I shall never be friends again with roses.’

SWINBURNE: The Triumph of Time

Table of Contents

Cover (#ufe4839d6-186d-544b-8cf5-b6515f9349dc)

Title Page (#u0b136a1f-902c-5efe-a6e2-067da5d7d8b2)

Copyright (#u20f6186e-4464-546a-ad41-74546161c9f8)

Epigraph (#u46f832da-84fa-53e7-8da5-7095d35e0672)

PART ONE (#u4d6c1dd6-7d9a-5372-bf6f-c876000324c7)

1: MISCHIEF (#ub63c0901-24a1-58cc-b4cf-8b6bfaff66aa)

PART TWO (#u6067d1ed-b262-5eae-bb2f-8267856fc4d2)

1: DANDY DICK (#u4cbcd5f7-c5f7-5a67-8ae9-291c1bc4222e)

2: BLESSINGS (#u2032873e-3028-5948-93db-fcfdeda63c26)

3: YESTERDAY (#ubac79347-e04c-5b25-82ca-6e1781a4a97e)

4: CAFÉ (#u694219e5-0784-5006-860a-41cec352b164)

5: PERFECTA (#u578f7684-ef57-597c-90c6-abb43aae06ee)

6: RIPPLES (#u6780171a-8f32-5a0e-bcfb-ae8f337ee315)

7: COPPER DELIGHT (#ua00072ae-3923-5bd4-824b-4f03fc230580)

8: BLUE MOON (#uec1e164c-1fcc-50a4-8a98-db38c607d020)

9: ESCAPADE (#litres_trial_promo)

10: MOONLIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

11: DESPERADO (#litres_trial_promo)

12: EVENSONG (#litres_trial_promo)

13: MASQUERADE (#litres_trial_promo)

14: NEMESIS (#litres_trial_promo)

PART THREE (#litres_trial_promo)

1: NEWS (#litres_trial_promo)

2: MEMORIAM (#litres_trial_promo)

3: BLACK BOY (#litres_trial_promo)

4: BLUSH RAMBLER (#litres_trial_promo)

5: ICEBERG (#litres_trial_promo)

6: CLYTEMNESTRA (#litres_trial_promo)

7: EMOTION (#litres_trial_promo)

8: INNOCENCE (#litres_trial_promo)

9: PENELOPE (#litres_trial_promo)

PART FOUR (#litres_trial_promo)

1: HAPPINESS (#litres_trial_promo)

2: SOUVENIR D’UN AMI (#litres_trial_promo)

3: WILL SCARLET (#litres_trial_promo)

4: SUMMER SUNSHINE (#litres_trial_promo)

5: DAYBREAK (#litres_trial_promo)

6: FÉLICITÉ ET PERPÉTUE (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PART ONE (#ulink_a9bb69c6-9749-5c2c-abae-7fda4b622003)

Or, quick effluvia darting through the brain, Die of a rose in aromatic pain.

POPE: Essay on Man

1 MISCHIEF (#ulink_25c8caa5-c773-5920-952a-abc540c681f6)

(Hybrid tea, coral and salmon, sweetly scented, excellent in the garden, susceptible to black spot.)

Mrs Florence Aldermann was distressed by the evidence of neglect all around her. Old Caldicott and his gangling son, Dick, had been surly ever since she had made it clear last autumn that far from being willing to admit the latter’s insolent, nose-picking fifteen-year-old to the payroll, she was contemplating charging his elders for the barrowloads of fruit he had stolen from the orchard. Scrumping, old Caldicott had said. Theft, she had replied, and as she knew from her connections with the Bench that young Brent Caldicott had made several appearances in juvenile court already, she was not to be disputed with.

After that the youth had disappeared, but his father and grandfather had clearly been nursing a grievance ever since. Her recent indisposition had given them their chance.

There would have to be words. More than words. If she could find somebody to take their place, heads would roll. The thought fathered the deed.

Angrily seizing a Mme Louis Laperrière in her gloved hand, grasping it firmly to prevent unsightly spillage, she picked her spot, applied the razor-edged knife expertly, and with a single smooth slice removed the sadly drooping head which she dropped into a plastic bucket.

Only then did she become aware that she was being watched.

Behind the mazy frame of sweet peas which divided the main rose-garden from the long lawn running down to the orchard (and which, she noted angrily, had been allowed to form seed-pods that, unremoved, would pre-empt flower growth) lurked a slight figure completely still.

‘Patrick!’ called Mrs Aldermann sharply. ‘Come here!’

Slowly the boy emerged.

Aged about eleven, small still for his age, he had large brown eyes in a pale oval face which was almost oriental in its lack of expression. Mrs Aldermann regarded him with distaste. It wasn’t just that he belonged to the same ghastly subspecies as Brent Caldicott, though that would have been enough. But in addition she could never look upon Patrick without thinking of his origins, and then the anger came welling up. It took little to uncap her vast pool of wrath, and in particular any display of human weakness brought it fountaining forth.

She had been angry eleven years earlier when her niece, Penelope, had announced that she was pregnant. She had been angrier when the feckless girl had refused to name the father, and angriest of all when she had calmly announced her intention of bringing up the child single-handed. Even Penelope’s feckless mother, Florence Aldermann’s younger sister, had had the wit to get a wedding ring from the object of her particular folly, George Highsmith, carpet salesman, though neither this nor the fact that they were both dead prevented Mrs Aldermann from still feeling angry with them. No, death was no barrier to anger; indeed it could be a cause of it. She still felt furious at her own husband’s display of weakness in dying of a coronary thrombosis, with so much still to do, so much still to expiate, in these very gardens two years before.

And finally her anger had turned upon herself when she collapsed in Knightsbridge on a pre-Christmas shopping expedition six months earlier. To be taken ill was deplorable; to have suffered a heart-attack, which she’d come to regard as a typically masculine form of weakness, was unforgivable.

Fortunately (she saw this now, though at the time she’d tended to blame her, as if ‘weakness’ were an infectious condition) she’d been with Penelope at the time, good-natured, unflappable Penny who had not taken the least offence (indeed, why should she?) when told after her Uncle Eddie’s death that the charitable allowance he’d been making her for so many years would have to stop, times and taxes being so hard, and who had seemed quite satisfied with the substitution of tea at Harrod’s on her Aunt Flo’s bi-annual London visits.

A few weeks later the ’sixties dawned. Could Mrs Aldermann have foreseen flower-power, pop-art, swinging London and all the age’s other lunar and lunatic achievements, she would have greeted it with vast indignation. As it was, the best she could manage in her state of ignorance and intensive care was vast indifference. Shortly afterwards she recovered enough to transfer to a luxurious private clinic. Her first real emotion and almost her second heart-attack occurred when she was well enough to enquire how much it was costing her. As soon as possible thereafter she declared herself fit enough to return to Rosemont, her Yorkshire home, to convalesce. Clearly unable to look after herself properly, she, with her doctor’s help, persuaded her easy-going untied-down niece to accompany her, a large saving on a professional nurse. And during the weeks that followed, Mrs Aldermann had come to value Penelope for more than purely economic considerations. She was what all self-regarding, moderately wealthy ladies of the middle class long for: a treasure. Hard-working, easy-going, entertaining of speech and unresentful of indignity, she fell short only in the department of subservient gratitude. And, of course, of Patrick.

But even with these deficiencies admitted, Mrs Aldermann as she recovered had begun to toy with the idea of offering Penny a permanent place at Rosemont which was far too large for one old woman living by herself. There would be no question of salary, of course – they were after all blood relations – but a small allowance would be in order, and there would be the large inducement of a change of will substantially in Penny’s favour.

The proposal had been made. To her amazement and irritation, instead of jumping gratefully at the chance, the feckless girl had looked dubious and talked rather nostalgically of London. What had London to compare with this pleasant old house of Rosemont with its fine gardens, beautiful views, and all of Yorkshire’s loveliest towns within easy striking distance? She had once seen the kind of place her niece lived in, a dingy two-roomed basement flat in a district where the bus queue looked like an audition for the Black and White Minstrel Show. Why should she need time to think about so incredibly generous an offer which had even included the not altogether unselfish undertaking to place Patrick at a modest though decent private boarding-school?

So now the sight of the boy spying on her added its weight to her already great burden of anger and she opened her mouth to utter a peremptory dismissal.

But before she could speak, he said, ‘Uncle Eddie used to do that.’

Taken by surprise – this was after all to the best of her recollection the first time the boy, in any of his visits, had ever actually initiated an exchange with her – she replied almost as if he were a real person.

‘Yes, he did,’ she said. ‘And Caldicott might have done it. But he didn’t. So now I have to do it.’

Her intonation placed old Caldicott and her dead husband in the same category of duty-neglecters. She sliced off another sweet-smelling but overblown Mme Louis Laperrière with emphatic deftness.

‘Why do you do it?’ demanded Patrick.

His tone was a trifle brusque but she graciously put this down to the awkwardness of a tyro.

‘Because,’ she lectured, ‘once the flowers have bloomed and begun to die, they inhibit – that is to say, they stop – other young flowers from developing and blooming. Also the petals fall and make the bush and the flower-beds look very untidy. So we cut off the blooms. It’s called deadheading.’

‘Deadheading,’ he echoed.

‘Yes,’ she said, beginning to enjoy the pedagogic mood. ‘Because you cut off the deadheads, you see.’

‘So the young flowers can grow?’ he said, frowning.

‘That’s right.’

This was the first time she had ever seen the boy really interested in anything. His expression was almost animated as he watched her work. She felt quite pleased with herself, like a scientist making an unexpected breakthrough. Not that she had ever felt it as a loss that she and the boy did not communicate. On the contrary, it suited her very well. But this particular form of intercourse which underlined her own superiority was far from unpleasant. She almost forgot to be angry, though the evidence of old Caldicott’s indolence was there in her plastic bucket to keep her wrath nicely warm. As though touched by her thought, the boy held up the bucket to catch the falling blooms.

She regarded him with the beginnings of approval. It occurred to her that she might by chance have stumbled on the key to his soul. Surprised by such a fanciful metaphor, she hesitated for a moment. But then her unexpected fantasy, like a bird released from the narrow cage in which it has been all its life confined, went soaring. Suppose that in Patrick’s urban bed-sit-conditioned body there lurked a natural gardener, longing to be called forth? This would make him in the instant a valuable – and costless – labourer! Then, as he grew richer in experience and knowledge, he could take over more and more responsibility for the real work of planning and propagation. In a few short years, perhaps, old Caldicott’s surly reign could be brought to a satisfying abrupt end, and with it the assumed succession of the gangling Dick and the unspeakable Brent.

For the first time in her life, she bestowed the full glow of her smile on the small boy and said in a tone of unprecedented warmth, ‘Would you like to try, Patrick? Here, let me show you. You take hold of the deadhead firmly so that you don’t let any petals fall and at the same time you have a good grip on the stem. Then look down the stem till you see a leaf, preferably with five leaflets and pointing out from the centre of the bush. There’s one, you see? And look, just where the leaf joins the stem you can see a tiny bud. That’s the bud we want to encourage to grow. So about a quarter-inch above it, we cut the stem at an angle, with one clean slice of the knife. So. There. You see? No raggedness to encourage disease. A clean cut. Some people use secateurs but I think that no matter how good they are, there’s always the risk of some crushing. I prefer a knife. The very finest steel – never stint on your tools, Patrick – and with the keenest edge. Here now, would you like to try? Take the knife, but be careful. It’s very sharp indeed. It was your Great-uncle Eddie’s. He planted most of these roses all by himself, did you know that? And he never used anything but this knife for pruning and deadheading. Here, take the handle and see what you can do.’

She handed the boy the pruning knife. He took it gingerly and examined it with a pleasing reverence.

‘Now let’s see you remove this deadhead,’ she commanded. ‘Remember what I’ve told you. Grasp the flower firmly. Patrick! Grasp the flower. Patrick! Are you listening, boy?’

He raised his big brown eyes from the shining blade which he had been examining with fascinated care. The animation had fled from his face and it had become the old, indifferent, watchful mask once more. But not quite the same. There was something new there. Slowly he raised the knife so that the rays of the sun struck full on the burnished steel. He ignored the dead rose she was holding towards him and now she let go of it so that it flapped back into the bush with a force that sent its fading petals fluttering to the ground.

‘Patrick,’ she said taking a step back. ‘Patrick!’

There was a sting on her bare forearm as the thorns of the richly scented bush dug into the flesh. And then further up, along the upper arm and in the armpit, there was a series of sharper, more violent stings which had nothing to do with the barbs of mere roses.

Mrs Aldermann shrieked once, sent a skinny parchment-skinned hand to her shrunken breast and fell backwards into the rose-bed. Petals showered down on her from the shaken bushes.

Patrick watched, expressionless, till all was still.

Then he let the knife fall beside the old woman and set off running up to the house, shouting for his mother.

PART TWO (#ulink_976124ca-bba5-5354-a066-d568cf7c9f0e)

The rose saith in the dewy morn: I am most fair; Yet all my loveliness is born Upon a thorn.

CHRISTINA ROSSETTI:

Consider the Lilies of the Field

1 DANDY DICK (#ulink_c75c5066-1eec-5ac9-8542-f7f01f6d528d)

(Floribunda. Clear pink, erect carriage, almost an H.T.)

Richard Elgood was a small dapper man with tiny feet to which his highly polished, fine leather shoes clung like dancing pumps.

Indeed, despite his sixty years, he advanced across the room with a dancer’s grace and lightness, and Peter Pascoe wondered if he should shake the outstretched hand or pirouette beneath it.

He shook the hand and smiled.

‘Sit down, Mr Elgood. How can I help you?’

Elgood did not return the smile, though he had a round cheerful face which Pascoe could imagine being very attractive when lit up with good humour. Clearly whatever had brought him here was no smiling matter.

‘I’m not sure how to begin, Inspector, though begin I must, else there’s not much point in coming here.’

His voice had the ragtime rhythms of industrial South Yorkshire, Pascoe noticed, rather than the oracular resonances of the rural north. He settled back in his chair, put his fingers together in the Dürer position, and nodded encouragingly.

Elgood ran his fingers down his silk tie as if to check the gold pin were still in position, and then appeared to count the mother-of-pearl buttons on the brocaded waistcoat beneath his soberly expensive business suit.

The buttons confirmed, he flirted with his fly for a moment, then said, ‘What I’m going to say is likely libellous, so I’ll not admit to saying it outside this room.’

‘My word against yours, you mean,’ said Pascoe amiably.

He didn’t feel particularly amiable. He’d spent much of the previous night in the midst of a rhododendron bush waiting for a gang of housebreakers who hadn’t kept their date. There’d been three break-ins recently at large houses in the area, all empty while the owners were on holiday, and all protected by alarm systems which had been circumvented by means not yet apparent to the CID. So a ‘hot’ tip on Sunday that Monday night was marked down for this particular house had had to be followed up. Pascoe had crawled out of his bush at dawn, returned to the station where, feeling too weary to write his report immediately, he had caught a couple of hours sleep on a camp bed. A pint of coffee in the canteen had then given him strength to complete his report and he’d just been on the point of heading home for a real sleep when Detective-Superintendent Andrew Dalziel had dropped this refugee from a Warner Brothers musical into his lap.

‘Please, Mr Elgood,’ he said. ‘You can be frank with me, I assure you.’

Elgood took a deep breath.

‘There’s this fellow,’ he said. ‘In our company. I think he’s killing people.’

Pascoe rested his nose on the steeple of his fingers. He would have liked to rest his head on the desk.

‘Killing people,’ he echoed wearily.

‘Dead!’ emphasized Elgood, as if piqued at the lack of response.

Pascoe sighed, took out his pen and poised it above a sheet of paper.

‘Could you be just a touch more specific?’ he wondered.

‘I can,’ said Elgood. ‘I will.’

The affirmation seemed to release the tension in him for suddenly he relaxed, smiled with great charm, displaying two large gold fillings, and produced a matching cigarette case with legerdemainic ease.

‘Smoke?’ he said.

‘I don’t,’ said Pascoe virtuously. ‘But go ahead.’

Elgood fitted his cigarette into an ebony holder with a single gold band. A gold lighter shaped like a lighthouse appeared from nowhere, twinkled briefly and vanished. He drew on his cigarette twice before ejecting it into an ashtray.

‘Mr Dalziel spoke very highly of you when I rang,’ said Elgood. ‘Either you’re very good or you owe him money.’

Again he smiled and Pascoe felt the charm again.

He returned the smile and said, ‘Mr Dalziel’s a very perceptive man. He apologizes again for not being able to see you himself.’

‘Aye, well, I won’t hide that I’d rather be talking to him. I’ve known him a long time, you see.’

‘He’d probably be available tomorrow,’ said Pascoe hopefully.

‘No, I’m here now, and I might as well speak while it’s fresh in my mind. If Andy Dalziel says you’re all right to talk to, then that’s good enough for me.’

‘And Mr Dalziel told me that anything you had to say was bound to be worth listening to,’ said Pascoe, hoping to achieve brevity if he couldn’t manage postponement.

What Dalziel had actually said was, ‘I haven’t got time to waste on Dandy Dick this morning, but he’s bent on seeing someone pretty quick, so I’ve landed him with you. Look after him, will you? I owe him a favour.’

‘I see,’ said Pascoe. ‘And you repay favours by not letting people see you?’

Dalziel’s eyes glittered malevolently in his bastioned face like a pair of medieval defenders wondering where to pour the boiling oil, and Pascoe hastily added, ‘What precisely does this chap Elgood want to talk to us about?’

‘Christ knows,’ said Dalziel, ‘and you’re going to find out. Take him serious, lad. Even if he goes round the houses, as he can sometimes, and you start getting bored, or if you’re tempted to have a superior little laugh at his fancy waistcoats and gold knick-knacks, take him serious. He came up from nowt, he’s sharp, he’s influential, he’s not short of a bob or two, and he’s a devil with the ladies! I’ve bulled you up to him, so don’t let me down by showing your ignorance.’

At that moment Dalziel had been summoned to the urgent meeting with the ACC which was his excuse for not seeing Elgood.

‘Here, I’ll need some background,’ Pascoe had protested in panic. ‘Who is he, anyway? What’s he do?’

But Dalziel had only smiled from the doorway, showing yellow teeth like a reef through sea-mist, ‘You’ll have seen his name, lad,’ he said. ‘I’ll guarantee that.’

Then he’d gone. Pascoe was still none the wiser, so now he put on a serious, no-nonsense expression.

‘Can we get down to details, Mr Elgood? This man we’re talking about, he works for your company, you say? Now, your work … what does that involve precisely?’

‘My work?’ said Elgood. ‘I’ll tell you about my work. I went into the army at eighteen, right at the start of the war. I could’ve stayed out easy enough, I was down the pit at the time, coal-face, and that was protected. But I thought, bugger it, I can spend the rest of my life hacking coal. So I took the king’s shilling and went off to look at the world through a rifle sight. Well, among all the bad times, I managed a few good times, and I wasn’t ready to go back down the pit when I came out. I’d put a bit of cash together one way and another, and I had a mate who was thinking the same way as me. We put our heads together to try to work out what’d be best to do. There was a shortage of everything in them years, so there was no shortage of opportunity, if you follow me. In the end, we settled on something to do with the building trade. Reconstruction, modernization, no matter how you looked at it, that was a trade that had to flourish.’

‘So you went into building,’ said Pascoe, with a sense of achievement.

‘Did I buggery!’ protested Elgood. ‘Do you know nowt about me? Me and my mate thought about it, I admit. But then we stumbled on this little business just about closed down during the war. They made pot-ware. Mainly them old jug-and-basin sets, you’ll likely have seen ’em in the antique shops. Jesus, the price they ask! It makes me weep sometimes to think …’

‘Elgood-ware!’ exclaimed Pascoe triumphantly. ‘On the lavatory bowls. I’ve seen it!’

‘I’ve no doubt you have if you’ve been around these parts long enough to pee,’ said Elgood smugly. ‘Though them with the name on’s becoming collectors’ pieces too. Lavs, washbasins, baths, sinks, we did the lot. It was hard to keep up with demand. Too many regulations, too little material, that was the trouble, but once you got the stuff, you stuffed the rules, I tell you. We expanded like mad. Then the technology began to change. It was all plastic and fibreglass and new composition stuff and we needed to refit throughout to keep up. There was no shortage of finance, we were a go-ahead business with a first-class record and reputation, but once the word gets out you’re after money, the big boys start moving in. To cut a long story short, we got taken over. We could have gone it alone, I was all for it myself, but my partner wanted out, and I.C.E. made a hell of a generous offer, with me guaranteed to stay in charge. Of course, the name disappeared from the company paper, but so what? I can take you to a hundred places round here where you can still see it. Some people write their names on water, Mr Pascoe. I wrote mine under it, mainly, and it’s still there when the water runs away!’

Pascoe smiled. Despite Elgood’s prolixity and his own weariness, he was beginning to like the man.

‘And the company’s name. Was it I.C.E. you said?’ he asked.

‘Industrial Ceramics of Europe, that means,’ said Elgood. ‘The UK domestic division’s my concern. Brand name Perfecta.’

‘Of course,’ said Pascoe. ‘I’ve driven past the works. And it’s there that these er-killings are taking place?’

‘I never said that. But he’s there. Some of the time.’

‘He?’

‘Him as does the killings.’

Pascoe sighed.

‘Mr Elgood, I know you’re concerned about confidentiality. And I can understand you’re worried about making a serious allegation against a colleague. But I’ve got to have some details. Can we start with a name? His name. The one who’s doing the killings.’

Elgood hesitated, then seemed to make up his mind.

Leaning forward, he whispered, ‘It’s Aldermann. Patrick Aldermann.’

2 BLESSINGS (#ulink_acf6b402-4882-56f1-a6e0-a84b1c8739c5)

(Hybrid tea. Profusely bloomed, richly scented, strongly resistant to disease and weather.)

Patrick Aldermann stood in his rose-garden, savoured the rich bouquet of morning air and counted his Blessings.

There were more than a dozen of them. It was one of his favourite HTs, but there were many close rivals: Doris Tysterman, so elegantly shaped, glowing in rich tangerine; Wendy Cussons, wine-red and making the air drunk with perfume; Piccadilly, its gold and scarlet bi-colouring dazzling the gaze till it was glad to alight on the clear rich yellow of King’s Ransom.

In fact it was foolish to talk of favourites either of variety or type. The dog-roses threading through the high hedge which ran round his orchard filled him with almost as much delight as the dawn-red blooms of the huge Eos bush towering over the lesser shrubs which surrounded it. It was beginning to be past its best now as June advanced, but the gardens of Rosemont were geared to bring on new growth and colour at every season so there was little time for regret.

He strolled across a broad square of lawn which was the only part of the extensive garden which fell short of excellence. Here his son David, eleven now and in his first year at boarding-school, played football in winter and cricket in summer. Here his daughter Diana, bursting with a six-year-old’s energy, loved to splash in the paddling pool, burrow in the sand-pit and soar on the tall swing. There would be a time when these childish pleasures would be left behind and the lawn could be carefully brought back to an uncluttered velvet perfection. Something lost, something gained. Nature, properly viewed, ruled by her own laws of compensation. She was the great artist, though permitting man sometimes to be her artisan.

Now in his early thirties, Patrick Aldermann presented to the world a face unscarred by either the excoriant lavas of ambition or the slow leprosies of indulgence. It was a gentle, almost childish face, given colour from without by wind and weather rather than from within. His characteristic expression was a blank touched with just a hint of secret amusement. His deep brown eyes in repose were alert and watchful, but when his interest was aroused, they opened wide to project a beguiling degree of innocence, frankness and vulnerability.

They opened wide now as his daughter appeared on the terrace outside the french windows and shouted shrilly over the fifty yards that separated them, ‘Daddy! Mummy says we’re ready to go now or else I’ll be late and Miss Dillinger will be unpleased with me.’

Aldermann smiled. Miss Dillinger was Diana’s teacher at St Helena’s, a small private primary school which made much use in its advertising of the word exclusive. Miss Dillinger’s expression of displeasure, I am unpleased, had passed into local monied middle-class lore.

‘Tell Mummy I just want a word with Mr Caldicott, then we’ll be on our way.’

He’d seen the Caldicotts’ old green van bumping along the drive round the side of the house and coming to a halt beside the brick built garden store. His great-aunt, Florence, would have been not unpleased to learn that old Caldicott had been carried off some few years after herself by septicaemia brought on by first ignoring, then home-treating, a nasty scratch received during his gardening duties. But gangling Dick had taken over the business and, in partnership with the delinquent Brent, had dignified it with the title ‘Landscape Gardeners’, and Patrick Aldermann now paid more for the firm’s services two days a week than Aunt Flo had paid old Caldicott full time for a month. They did have greater overheads, of course, including a pair of occasional assistants, a tall youth in his mid-twenties who answered to Art and a miniature Caldicott, in his mid-teens and almost dwarfish of stature, who generally refused to answer to Pete. Aldermann’s wife, Daphne, able on occasion to turn a nice phrase, referred to them as Art longa and Peter brevis.

The gardeners had already got down to their essential preparations for work by the time Aldermann joined them. Art was heading up to the house to beg a kettle of water and cajole whatever was spare in the way of biscuits or cake out of Daphne or Diana; Brent was leaning against the van smoking a butt end; the dwarf Peter had vanished; and Dick, now a grizzled fifty-five-year-old, was studying which of the two keys he held would open the huge padlock which he opened every Tuesday and Wednesday of the year from March to November.

‘Mr Caldicott,’ said Aldermann. ‘A quick word. Someone went into my greenhouse yesterday and they left the inner door ajar. It’s essential that both doors are closed and that there’s never more than one open at a time.’

‘But there was only one left open, you said,’ replied Caldicott with a note of triumph.

‘Yes, but the other would have to be opened to get out, or, indeed, when I went in, so then they’d both be open, wouldn’t they?’ said Aldermann patiently. ‘In any case, there’s no need that I see for anyone to enter the greenhouse.’

Art returned from the house bearing water and a biscuit tin.

‘Mrs Aldermann says, will you be long?’ he said cheerfully.

Aldermann nodded an acknowledgment and made for the house. Behind him, Caldicott tried the wrong key.

Aldermann’s daughter and his wife were already sitting in the dusty green Cortina. Normally Daphne Aldermann drove her daughter to school in her own VW Polo, but two days earlier it had been scratched by vandals in a car park and had had to be taken in for a respray.

‘Sorry,’ said Aldermann, sliding into the driving seat. ‘I wanted a word with Caldicott.’

‘And I wanted to get to school in time to have a word with Miss Dillinger,’ said Daphne with a frown, but only a slight one. She was used to coming second to horticulture.

‘The postman’s been,’ she said. ‘There were some letters for you. I’ve put them in the glove compartment in case you have a quiet moment during the day.’

‘I’ll see if I can find one,’ he murmured and set the car in motion.

Daphne Aldermann gazed unseeingly over the extensive gardens of Rosemont as the Cortina moved down the gravelled drive. She was a good-looking woman in that rather toothy English middle-class way which lasts while firm young flesh and rangily athletic movement divert the eye from the basic equininity of the total bone structure. Four years younger than her husband, she still had some way to go. She had married young, announcing her engagement on her eighteenth birthday to the mild perturbation of her widowed father, a Church of England Archdeacon with fading episcopal ambitions. A wise man, he had not exerted his authority to break the engagement but merely applied his influence to stretching it out as long as possible in the hope that it would either prove equal to the strain, or snap. Instead, death had snapped at him, and his objections and presumably his ambitions had been laid to rest with him in the grave.

After a short but distressingly intense period of mourning, Daphne had embraced the comforts and supports of marriage. Her elderly relatives had not approved the haste. There had been talk and reproving glances and even some accusatory hints, though with that magnanimity for which upper-middle-class High Anglicans are justly renowned, a comfortable majority agreed that Daphne’s contribution to her father’s untimely death had been one of manslaughter by distraction rather than murder by design.

Happily Daphne, even in the guilt of grief, was clear-headed enough to feel conscientiously disconnected from the slab of rotten masonry which, falling from the tower of the sadly neglected early Perpendicular parish church he was inspecting with a view to launching a restoration appeal, had dispatched the Archdeacon. Now, twelve years and two children later, she too was aware she had many blessings to count, but close communion with her husband was not one of them. He wore around him an unyielding carapace of courtesy against which her anxieties beat in vain. Perhaps ‘carapace’ was the wrong image. It was more like an invisible but impenetrable time-capsule that he inhabited, which hovered in, but did not belong to, simple mortal linear chronology. He treated the future as if it were as certain as the past. It was odd that in the end such certainties should have driven her to the edge of panic. And over.

The leaky byways which formed their winding route from Rosemont were awash with morning sunshine, but clouds were waiting above the main trunk road and by the time they entered the stately outer suburb in which St Helena’s stood, the sky was black. Aldermann regarded it with the complacency of one whose application of systemic insecticide the previous evening would already have been absorbed into the capillaries of his roses.

Daphne said, ‘Oh bother.’

‘I can easily wait and drive you into the town centre,’ offered Aldermann, thinking she was referring to the weather.

‘Thanks, but don’t worry. I rather fancy the walk and I’m sure it’ll only be a shower. No, it was that lot I was oh-bothering about.’

Aldermann had already observed ‘that lot’ with some slight curiosity as he slowed down outside the large Victorian villa which had been converted into St Helena’s School. The ‘lot’ consisted of four women each carrying a hand-painted placard which read variously: WHAT DO YOU THINK YOU’RE PAYING FOR? WHAT PRICE EQUALITY? PRIVATE SCHOOLS = PUBLIC SCANDALS and, at more length, ST HELENA FOUND THE TRUE CROSS, THE REST OF US ARE BEARING IT. Two of the women were carrying small children in papoose baskets.

Aldermann drove slowly along a row of child-delivering Volvos till he found a kerbside space.

‘Isn’t it illegal?’ wondered Aldermann as he parked. ‘Obstruction, perhaps?’

‘Evidently not. They don’t get in the way and they only speak if someone addresses them first. But it could upset the children.’

Aldermann looked at his daughter. She did not seem upset. Indeed she looked very impatient to be out of the car. She also looked very pretty in her blue skirt, blue blazer with cream piping, cream blouse, and little straw boater with the cream and blue ribbon.

‘As long as they don’t try to talk to them,’ he said. ‘Goodbye, dear.’

He kissed his wife and daughter and watched as they walked along the pavement together. As forecast, none of the picketing group made any movement more menacing than a slight uplifting of their placards. At the school gate, Daphne and Diana turned and waved.

Aldermann waved back and drove away, thinking that he was indeed a well-blessed man. Even the rain which was now beginning to fall quite heavily was exactly what the garden needed after nearly a fortnight of dry weather. He switched the windscreen-wipers on.

Daphne Aldermann coming out of St Helena’s fifteen minutes later did not feel quite so philosophical about the rain. Her talk with Miss Dillinger, albeit brief, had isolated her from potential lift-givers just long enough for the kerbside crowd of cars to have almost entirely disappeared.

Turning up the collar of her light cotton jacket, she put her head down into the rising wind and, hugging the shelter of the pavement trees, headed townwards. There was a car still parked about fifty yards ahead, a green Mini some five or six years old. A woman was leaning over the front seat putting a baby of about nine months into a baby seat at the rear. The woman was long-limbed, athletically slender, with short black hair and positive, clear-cut features which just stopped this side of wilfulness. There was something familiar about her and Daphne smiled hopefully as she completed her task and straightened up at her approach.

The woman regarded her with clear grey eyes and a half smile as the rain came lashing down.

‘You look as though you’d like a lift,’ she said.

‘Thanks awfully. That’s really most kind of you,’ said Daphne, making round to the passenger door with no further ado. But as she stooped to get in, her eye caught something on the rear seat under the baby. Upside down, the words St Helena jumped out at her. It was a protest placard.

‘It’s all right,’ said the woman behind the wheel. ‘No proselytizing. Just a lift. But it’s up to you.’

She started the engine. The wind wrapped damp fingers around Daphne’s trailing leg.

She pulled it in and shut the car door.

‘What a lovely little boy,’ she said brightly, nodding at the blue-clad baby who nodded back as the car accelerated over a bumpy patch of road.

‘No,’ said the driver.

‘No?’

‘Little, I’ll grant you. But not lovely. And not a boy. My daughter, Rose.’

‘Oh, I’m sorry.’

‘Don’t be. It’s a nice test of anti-stereotyping.’

‘Really? Well, I still think she’s lovely.’

The woman rolled her grey eyes briefly, but Daphne caught the contumely. It was not a safe way in which to treat an Archdeacon’s daughter.

‘And you,’ she resumed with increased brightness. ‘Are you Rose’s mother? Or her father?’

The woman looked at her in surprise, then threw back her head and laughed so fervently that the car did a little chicanery on the straight road, and Rose, stimulated by either the movement or the laughter, suddenly chortled merrily.

‘Mother,’ said the woman. ‘I’m Ellie. Ellie Pascoe.’

‘Daphne Aldermann,’ said Daphne. ‘How d’you do?’

‘How d’you do,’ said Ellie gravely. ‘You know, I came out so quick this morning that I didn’t have time for any breakfast. Do you fancy a coffee and a bacon buttie?’

‘Why not?’ said Daphne, determined to meet boldness with boldness.

‘Why not, indeed?’ said Ellie, and laughed again.

3 YESTERDAY (#ulink_d45a51e3-bf00-5412-ab5f-9b4e38956d7b)

(Floribunda. Multitudinous tiny lilac-pink flowers with an olde-worlde fairy-tale air.)

‘So Dandy Dick’s finally gone doolally,’ repeated Detective Chief Superintendent Andrew Dalziel, apparently much taken by the assonance and alliteration.

‘I didn’t say that,’ protested Pascoe.

‘Look, lad,’ said Dalziel, ‘you spent the best part of yesterday morning with the man. Have them gold fillings finally rotted his brain or not? It wouldn’t surprise a lot of folk. There’s always been something not quite right about Elgood. Not marrying, and all those fancy waistcoats.’

‘Queer, you mean?’ said Pascoe

Dalziel looked at him in disgust.

‘Don’t be daft,’ he said. ‘He’s tupped more typists in his in-tray than you’ve had hot dinners. There’s many won’t use a lav with his name on it for fear it makes a grab at them. No, he’s just a bit eccentric, that’s all. Nothing you’d look twice at in one of them walking adenoids from Eton; but from a miner’s lad out of Barnsley, you expect plain dressing, plain speaking, and likely a plain wife and six plain kids.’

‘He must be a great disappointment to all his friends,’ agreed Pascoe. ‘But he didn’t strike me as at all unbalanced yesterday. I think he was genuinely reluctant to be making the accusation. He got it out very quick in general terms to start with, almost as though he wanted to commit himself. After that, it took a bit more time, but mainly because, once there was no going back, he relaxed and reverted to what by your account is his more normal mode of speaking.’

‘Oh aye, he goes round the houses like a milkman’s horse, Dick,’ said Dalziel.

Pascoe smiled. His stomach suddenly rumbled and he recalled that he had missed his breakfast that morning. Ellie had been in a hurry, and when he discovered the cause and hinted a doubt whether a picket line was the right place for a nine-month-old-baby, what little time there might have been for the preparation of toast and coffee had been consumed in a heated discussion. Very heated, though not quite at flaming row temperature. Rain beat at the window of Dalziel’s office. He hoped that Ellie wasn’t still striding round somewhere with a banner above and little Rosie behind, dripping in her papoose basket. His stomach rumbled again.

‘You should get up early enough to eat a cooked breakfast,’ commented Dalziel. ‘You’re like something out of Belsen. Me, I was built up on eggs and rashers.’

He beat his stomach complacently and belched. Diets had failed to make any inroads on his waist and recently he had taken to citing his stoutness as evidence of health rather than the cause for concern his doctor believed.

‘I should hope to learn from your example, sir. Now, about Elgood, what do you want me to do?’

It was a blunt question, arising from Pascoe’s determination not to be left with the responsibility for examining or ignoring Dandy Dick’s allegations.

‘Let’s have an action replay of what you’ve got so far,’ said Dalziel, leaning back and closing his eyes.

Pascoe risked a long-suffering sigh and said in a rapid and expressionless voice, ‘The two alleged victims are Brian Bulmer, Perfecta’s financial director, and Timothy Eagles, the Chief Accountant. Bulmer died in a car accident after the office Christmas party. No other vehicles involved, icy road, and his bloodstream showed up at nearly two hundred over the limit. Eagles had a heart attack in a washroom next to his office. The cleaner found him dead.’

‘What’s Dick say Aldermann’s got to do with this?’ interrupted Dalziel.

‘I was getting to that. Aldermann was drinking with Bulmer at the party, or rather plying him with drink, according to Elgood. And he shared the washroom with Eagles.’

‘Post mortem reports?’

‘In Bulmer’s case, death from multiple injuries, and the alcohol level noted. In Eagles’s case, no post mortem. There was a previous history and his doctor was content to issue the certificate. No chance of back-tracking. They’re both ash now.’

‘Just as well, mebbe,’ said Dalziel, yawning, ‘Motive?’

Pascoe said, ‘Ambition. Or rather, money.’

‘Make up your mind!’

‘Well, he doesn’t reckon Aldermann’s interested enough in his work to be ambitious, but he thinks he needs more money. Getting on the Board would shove his income up considerably.’

‘But he must have known that he’d be competing against his immediate boss, this fellow, Eagles,’ said Dalziel. ‘Why not knock Eagles off first?’

‘Elgood had worked all that out. His theory is that what Aldermann was after initially was just Eagles’s job. He saw his chance to get Bulmer out of the way which would probably mean Eagles’s elevation, leaving a gap for Aldermann to fill. It wasn’t till after Bulmer’s death, when certain anti-Elgood elements on the Board started talking about nominating Aldermann merely in order to annoy and embarrass the Chairman, that he got the scent of a bigger prey.’

‘Bloody hell,’ said Dalziel, opening his eyes and sitting upright. ‘And Dick really believes this?’

‘That’s why he was here. Though I think the more he talked it through – which was a great deal more, I’ve cut it down by at least ninety-nine per cent – the dafter it sounded to him. But he stuck to his guns.’

‘Oh, he’d do that all right, would Dick,’ grunted Dalziel. ‘But there must’ve been something brought it on in the first place.’

‘Two things,’ said Pascoe. ‘Evidently he had some kind of row with Aldermann last Friday. He made it clear to Aldermann that even though Eagles was dead, he was still going to block his elevation to the Board. He had to go out to a meeting then, leaving Aldermann in his office. Later he returned and worked well into the evening, long enough to need his desklamp on. It’s one of those Anglepoise things. He pressed the switch and got hit by an electric shock which knocked him out of his chair. He recovered pretty quickly – he’s very fit for his age, he says, does a lot of swimming – and he put it down to a bad connection. But yesterday morning something else happened. He went to get his car out of the garage. It’s got one of those up-and-over doors. It seemed to be a bit stiff so he gave it a big heave and next thing, it came crashing down on top of him. Fortunately he’s a pretty nifty mover. He dropped flat and the door crashed on to the boot of his car. I’ve seen the dent it made and he can count himself lucky. So he crawled out a bit shaken and that’s when he rang you and started shouting murder.’

‘You’ve examined the garage door, I take it?’ said Dalziel.

‘Yes. It weighs a ton, but it just looked like the decrepitude of age to me. Still, the tech boys are taking a really close look at it, and I had someone collect the lamp from Elgood’s office too. At a glance, nothing shows. Just wires working loose and shorting. But I’ve told them to double check everything, seeing as he’s such a good friend of yours, sir.’

Dalziel ignored the gibe, looked towards his closed door and bellowed. ‘Tea! Two!’

The door rattled and even the disregarded telephone shifted uneasily on its rest and let out a plaintive ping.

‘Coffee for me,’ said Pascoe without hope.

‘Tea,’ said Dalziel. ‘Caffeine clogs the blood. That’s why all them Frog painters’ ears fell off, and God knows what else besides. Did Dick say he’d had another encounter with Aldermann on Monday? I mean, had he expressed surprise to see him still alive or anything?’

‘No. In fact, Mr Elgood seems to have kept out of the office on Monday. He went down to some cottage he owns on the coast. Presumably that’s how he keeps so fit swimming.’

‘Aye, that’s the least strenuous form of exercise that goes on down there, I gather,’ chortled Dalziel. ‘It’s stuck on the edge of a cliff that’s being eaten away by the sea. They say that every time Dick takes a new fancy woman down there, another bit gets shaken off.’

‘Too much caffeine, perhaps,’ said Pascoe. ‘Anyway, Aldermann wouldn’t need to see him to know he was still alive, would he? He’d have heard in the office if anything had happened.’

‘So you think there’s something in it, do you, Peter?’ asked Dalziel.

‘I didn’t say that,’ said Pascoe emphatically. ‘It all sounds very far-fetched to me.’

There was a perfunctory knock at the door, which opened immediately to admit a tin tray bearing two mugs and borne by a man distinguished by the elegant cut of his sober grey suit and the extreme ugliness of his asymmetrical features.

‘Either we’re overmanned or undermanned, Sergeant Wield,’ said Dalziel sarcastically. ‘Where’s that young tea-wallah?’

‘Police-Cadet Singh is receiving instructions on traffic duties at the market roundabout, sir,’ said Wield.

Cadet Shaheed Singh was the city’s first Asian police recruit, who had brought out all that was colonial in Dalziel. The boy came from a Kenyan Asian family and had been born and bred in Yorkshire, but neither bits of information affected Dalziel’s comments, which were at best geographically inaccurate, at worst criminally racist.

‘Well, it’ll make a change from rickshaws for the lad,’ he said, taking the larger of the two mugs and sipping noisily.

‘Tea,’ he diagnosed. ‘The cup that cheers.’

Pascoe took his mug and drank. It was coffee. He smiled his thanks at Sergeant Wield, winning a suspicious glance from Dalziel.

‘What’s Dick got against Aldermann, anyway?’ asked the Superintendent. ‘Why doesn’t he want him on the Board?’

‘Two reasons,’ said Pascoe. ‘First is, because it’s become a test of his authority as chairman. Aldermann’s appointment would be a serious defeat for him. Second, because he honestly doesn’t think Aldermann’s up to it. He reckons he cruises along, with only a token interest in the firm and his job.’

‘Is that right? Might be worth taking a look at this paragon,’ said Dalziel. ‘I could likely find him a slot in CID.’

Pascoe ignored this and said, ‘We can hardly just go barging in to his house, sir, and say we’re checking an allegation that he’s committed a couple of murders.’

Dalziel looked surprised, as if he could see no real objection to this way of proceeding. Sergeant Wield coughed and handed Pascoe a list of names and addresses.

‘That trouble in the multi-storey on Monday, sir,’ he offered as explanation. Dalziel looked exasperated. The ‘trouble’ referred to had been the vandalization of some parked cars by scratching their paintwork with a sharp metal instrument. It was not the kind of thing a sergeant was expected to interrupt his CID chief’s conference with.

Pascoe had more confidence in Wield. He examined the list. One of the names was underlined in red.

Mrs Daphne Aldermann. Rosemont House, nr. Garfield. VW Polo, metallic green, scratchings on bonnet.

He looked interrogatively at Wield, who said, ‘It’s his wife, sir, I checked.’

Pascoe showed the list to Dalziel who said, ‘So what?’

Pascoe said, ‘It’s an excuse to call, sir. Take a look at this Aldermann without him knowing.’

Dalziel continued to look doubtful. Wield tactfully withdrew.

‘Still,’ continued Dalziel, ‘if it’s your considered opinion that we should nose around a bit more, Peter …’

‘I didn’t necessarily mean …’

‘Sharp lad, that Wield,’ continued Dalziel. ‘Him and that darkie would make a grand pair on night patrol. The villains wouldn’t stand a chance. They’d not see one of ’em and one look at t’other would frighten the buggers to death! What else did he say when you discussed Dandy Dick with him?’

Suspecting a reproach, Pascoe said, ‘I trust his discretion as well as his judgement, sir. It’ll go no further. What he said was he’d rarely heard such feeble reasons for suspicion as those given by Elgood. Then he went off and came back an hour later to say that from what he’d been able to learn about Elgood, for him to come to us on such weak grounds he must either in your own phrase have gone doolally, or else there was something he hadn’t told us.’

Dalziel thought about this for a moment and then inclined his head in what Pascoe hoped might be the beginning of a nod but turned out to be only the beginning of a right-handed scratch down his spinal column, then across the left shoulder-blade.

Muffled, and apparently emerging from the stubble of greying hair which was all that Pascoe could see of the huge head, came Dalziel’s voice.

‘It’s your case, Peter. Keep me in touch, that’s all I ask. Just keep me in touch.’

‘Yes, sir,’ said Pascoe rising. ‘I will.’

When he left he took his mug with him, not doubting else that Dalziel would soon have been examining the grounds with all the keenness of a sadistic fortune-teller in search of disaster.

4 CAFÉ (#ulink_69f73162-ffdb-5a32-ba1e-74808d663f63)

(Floribunda. Unusual blend of coffee and cream in the opened bloom, useful in floral arrangements, sweet aroma.)

Ellie Pascoe dunked a gobbet of bread roll in her coffee, tested the temperature and then applied the soggy wad to her baby’s lips which sucked at it greedily.

Daphne Aldermann regarded the proceeding with some alarm.

‘Isn’t she rather young?’ she ventured.

‘Ignore all else but not this teaching,’ said Ellie, ‘that life is reached by over-reaching.’

‘What’s it mean?’ wondered Daphne.

‘Christ knows,’ said Ellie. ‘But don’t worry. The coffee in this place is mostly milk, sugar and chicory. But the bacon butties are divine, don’t you agree?’

This place had turned out to be a café, or more definitely, THE MARKET CAFF, a title printed in fading letters along a sagging lintel above a steamed-up window mistily overlooking the open-air market. Stall-holders drifted in and out, each, so far as Daphne could make out, on some personal timetable which meant that every combination of food, from breakfast fry-ups through tea-time cake-and-scones to cocoa-and-sandwich suppers, was in demand.

Ellie and Rose were obviously known here and it struck Daphne that Ellie greeted the many expressions of delight in the baby with none of that instant put-downery her own enthusiasm had provoked. She doubted if the balance of sincerity and conventionality here was much different from her own, so the solution could only lie in the source, but she had not plucked up courage to make this observation to this rather formidable woman when Ellie, whose grey eyes had been observing her with some amusement, said, ‘You’re quite right. Working-class crap is much more tolerable than middle-class crap because they’ve not had the chance to know better. On the other hand, my husband says thinking like that is itself a form of condescension and therefore divisive.’

‘He sounds a clever man. I wonder. Does he earn half as much as most of these workers who’ve not had the chance to know better?’

Ellie smiled. This blonde, horsey, country-set woman might turn out to be worth a smoking.

‘Probably not. But money’s not the really important thing in our class matrix, is it? And it’s certainly not brains, and it’s only incidentally birth. It’s education, not in the strict sense, but in a kind of masonic way. It’s learning all those little signals which say to other people look here, recognize me, I’m a member of the club. You start learning them in a very small way at places like St Helena’s, which is why I’m agin them. Also I can’t smoke and wave a banner at the same time and I’m trying to cut down on smoking. Have one.’

She offered Daphne a filter-tip which she took. They lit up. Ellie dragged deep on hers and said, ‘First of the day.’ Daphne took a quick, short puff, coughed violently and gasped, ‘First of the year.’

‘Why’d you take it then?’ said Ellie.

‘It’s hardly the most offensive thing I’ve taken from you this morning,’ said Daphne.

Ellie said, ‘You’re a sharp lady, lady.’

The door opened and Daphne who was facing it saw two policemen enter, removing capes dripping from the still pelting rain. One was an older man in the traditional tall helmet; the other wore the flat cap of a cadet beneath which a good-looking young Indian face peered out at the momentarily silenced customers, whose chatter instantly resumed when it became clear all that the newcomers were after was a cup of tea.

‘If I’m sharp, then it’s a sharpness I picked up at places like St Helena’s,’ said Daphne.

‘And boarding-school?’

‘I was a day-girl. It was only in Harrogate, but yes, it was a boarding-school.’

‘Well, to quote my husband again, that’s one thing you’ve got to give the English single-sex boarding-school. It teaches you to hold your own.’

The two policemen were coming up behind Ellie in search of a table. The elderly constable glanced down and to Daphne’s surprise his stern hello-hello-hello face broke into a smile.

‘Hello, Mrs Pascoe,’ he said. ‘How are you?’

Ellie looked up.

‘Well, hello, Mr Wedderburn,’ she said. ‘I’m fine.’

‘Haven’t seen you in here for a long time,’ continued the constable. ‘How’s the kiddy?’

Ellie’s eyes flickered towards her companion to see if she’d caught the implication of the policeman’s remark. She had.

‘Oh, she’s blooming. Blooming this, blooming that.’

‘Isn’t she good,’ said Wedderburn, impressed by the baby’s sang-froid.

‘In crowds and company and public places, yes,’ said Ellie. ‘She saves up her bad side for private performance only. She’ll make a good cop. Who’s your friend?’

‘This is Police Cadet Shaheed Singh,’ said Wedderburn gravely. ‘He’s just been learning that hell is the rush-hour on market days. Singh, this is Mrs Pascoe, Detective-Inspector Pascoe’s wife.’

The cadet smiled. He looked like one of those elegant handsome young princes who at one time always seemed to be playing cricket for England.

‘Nice to meet you, missus,’ he said in a broad Yorkshire accent which made Wedderburn’s sound like Eton and the Guards.

‘You too, Mr Singh,’ said Ellie. ‘Won’t you join us?’

Singh was clearly willing but Wedderburn said, ‘No, thanks, Mrs Pascoe. We’ll sit over here. There’s one or two of the finer points of traffic control I need to discuss with the lad here and you’d likely find it a bit boring. Nice to see you.’

They moved away.

‘Well!’ said Daphne. ‘So I’m in with the fuzz.’

The word sounded alien on her tongue, perhaps because her upper-class accent squeezed it almost into fozz.

‘And,’ she continued, pursuing her advantage, ‘far from being your daily port of call, this elegant establishment is merely a stage-setting to soften up your victims!’

‘Not quite,’ grinned Ellie. ‘But, OK, I did choose it specially this morning.’

‘To turn me into a Trot? Or, with your police connections, are you really an agent provocateur?’

‘What’s your husband do?’ asked Ellie.

‘He’s an accountant with Perfecta, you know, the bathroom people.’

Ellie looked momentarily surprised, then said, ‘And how’s your long division?’

‘Terrible,’ admitted Daphne. ‘But I don’t see … ah!’

‘We may be one flesh, but the minds have an independent existence, or should have. We are not our husbands, nor even our husbands’ keepers.’

‘I agree, to an extent,’ said Daphne. ‘But it’s not quite as simple as that, is it? I mean, if for instance, I told you my husband had committed a crime, wouldn’t you feel it necessary to tell your husband?’

Ellie considered this.

Finally she said, ‘I don’t know about necessary. Suppose I told you my husband was investigating your husband, would you feel it necessary to tell him?’

Now Daphne considered, but before she could answer she was interrupted by a large, handsome, middle-aged woman, rather garishly dressed and with an ornate rose-tinted hair-do, like a mosque at sunset, who was coming from the counter with a coffee in one hand and a wedge of chocolate gateau in the other.

‘Hello!’ she cried. ‘It’s Daphne Aldermann, isn’t it? Not often we see you in here. I always meant to keep in touch, dear, but it’s all so hectic, one mad round after another, time just flies, just flies. And so must I. What a lovely baby. Coming, darlings, coming.’

This last was in response to a chorus of Mandy! from a distant table where three men were sitting. The woman made a valedictory gesture with her gateau and went to join them.

‘So you’re not so out of your depth here as I thought,’ said Ellie. ‘I’ll have to look for somewhere really low. You should have asked your friend to sit down. She sounded interesting.’

‘You think so? Well, for a start, she’s hardly a friend. And in any case, there’s no way you’ll get Mandy Burke to join two women and a child when there’s anything in trousers imminent. Just flies is the perfect motto for her.’

‘Miaow!’ said Ellie, grinning broadly. ‘Mandy Burke? I’ve a feeling I’ve seen her around.’

‘She runs a stall in the old covered market. Cane and mats and curios, that sort of thing. It’s a little goldmine, I believe,’ said Daphne. ‘Mandy’s Knick-Knacks it’s called. That’s where you’ve probably seen her, unless your husband wines, dines and dances you at the best night spots a lot.’

‘And what makes you think he doesn’t?’ wondered Ellie. ‘But you’re right. I know the stall. And in which of her milieux did you meet her?’

‘Neither. Her husband used to work with mine, or the other way round really. He died about four or five years ago. I don’t think I’ve run into her more than a couple of times since. Widowhood seems to become her. I should imagine women like her are a bit of an embarrassment to the feminist movement. So confident, so secure, so able, but absolutely anchored in a masculine world.’

She spoke challengingly and Ellie was again surprised at the vein of aggression she was finding in this superficially stereotyped bourgeois housewife. But before she could reply, Rose suddenly let out an enormous burp, then smiled complacently at her admiring audience.

The two women laughed and Ellie said, ‘Let’s have another coffee.’

‘All right,’ said Daphne. ‘No, I’ll get them. Don’t worry, I won’t embarrass you by pushing to the front of the queue.’

She rose and made her way to the counter where Ellie was both amused and irritated to see four horny-handed sons of toil step back and wave this long, elegantly dressed, fair-haired lady to receive service before them.

5 PERFECTA (#ulink_8c883f79-2d33-524b-aa3e-874760ff8614)

(Bush. Vigorous growth, red-flushed blooms, heavy and susceptible to being snapped off in strong winds, otherwise long-lasting, some black spot.)

Patrick Aldermann sat at his desk in the office which still bore the name of Timothy Eagles on the door. It did not bother him. It took a great deal to bother him as the staff of Perfecta Ltd had long ago come to realize.

One of the junior sales executives had been moved by drink and seasonal bonhomie to philosophize on the subject to Dick Elgood at the office Christmas party the previous year.

‘It isn’t so much,’ he slurred ginnily into Elgood’s face, ‘that things run smoothly around Pat Aldermann, it’s more than no matter how many cock-ups have been cocked-up, he just keeps on running smoothly around things, you follow me?’

Elgood had used his nimbleness of foot to evade the man and headed for the bar, where he spotted the object of the analysis in close conversation with Brian Bulmer, the firm’s financial director, and a hawk-faced young man called Eric Quayle, an industrial chemist by training and a captain of industry by inclination, who was also on the Board and generally regarded as tomorrow’s man. My bloody heir presumptuous, Elgood called him, adding, but the bugger’s going to turn grey waiting.

Quayle saw Elgood and turned away from the other two. Bulmer was doing all the talking, Elgood noticed, and he guessed that most of the Scotch from the bottle between them had gone down his throat. As Quayle approached, Elgood grabbed two glasses from the bar and a half of Scotch.

‘Enjoying yourself, Eric?’ he asked as he moved away, but did not stay for an answer. Besides having little desire for a bout of horn-locking with Quayle, he was also ten minutes late for a rendezvous in his private office with the new invoice clerk, who was so well-bosomed that she had to stand sideways to see into a filing cabinet.

An hour later, he had just scaled this Alpine lady for the second time when the phone started ringing, rousing him from post-coital lethargy with the news that Brian Bulmer within minutes of leaving the party had skidded into the seasonal road-death statistics.

The death had cast a light pall over Christmas which as usual he spent alone in his seaside cottage, braving the North Sea’s icy waters for his traditional pre-luncheon swim. Experience had long ago taught him that shared Christmases bred sentimental notions which could lead to an unhappy New Year, so now it was his one celibate season and as he lay in his double bed, listening to the hungry tide gnawing at the cliff face, he had plenty of time to think about Bulmer’s death. He mourned the man’s passing but his main thought was about his successor. Timothy Eagles, the Chief Accountant, was the obvious man. Competent, predictable and loyal. He wanted such men about him and whatever he wanted, the Board would ultimately agree to. The memory of Bulmer and Quayle with the quiet watchful figure of Aldermann between them hardly stirred, not even when Quayle had tentatively wondered whether or not a younger man, like, say, Eagles’s assistant, Patrick Aldermann, might not be a more revitalizing addition to the Board. Quayle was just flexing his muscles. It meant nothing.

Then Eagles had died, collapsing in the washroom at the end of the corridor he shared with Aldermann.

Immediately it became clear that Quayle meant business and that he was not without support. The battle was about Aldermann’s candidacy for the Board, but the war was about Elgood’s chairmanship. Aldermann’s suitability didn’t worry Quayle and his supporters in the least. He was merely their instrument to probe, irritate and display Elgood’s vulnerability. The more blood they drew, the more support they would get.

He had started to use every weapon at his disposal and he had collected a formidable armoury. He had not even omitted the direct appeal to Aldermann himself. To win him to withdraw from the fray voluntarily was too great a coup not to be attempted. But things had gone wrong. Aldermann had hardly seemed to consider the matter worth bothering about. His detachment, his self-possession, the hint of secret amusement in his eyes, had got under Elgood’s guard. What had been intended as a subtle operation became a bludgeoning attack.

‘But it all seems so simple to me, Dick,’ Aldermann had said finally. ‘If I don’t get on, I don’t get on. Honestly, it won’t bother me, don’t worry about it for a moment. And if I do get on, the extra money will certainly come in very useful.’

It was then, vastly irritated that this conversation should have been mistaken as an expression of concern over Aldermann’s feelings, that Elgood had moved from bluntness to brutality, made it quite clear what his own feelings about the issue were and ended by half-shouting, ‘And if you get on to the Board of Perfecta, lad, it’ll be over my dead body!’

The little smile, the nod of farewell (or agreement?) and Aldermann had left, keen as always (Elgood guessed) to get back to his precious bloody roses, apparently quite unmarked by an interview whose memory continued to shoot little electric arrows of rage into Elgood’s chest for hours after.

Well, that had been last Friday and a very great deal had happened since then. For a time it had seemed as if things were getting out of control, rising to the climax of his visit to the police. That had been an error, but cathartic, and in the twenty-four hours since he had spoken to Pascoe, he had returned to something like full control and true perspectives. The real issue was his own control of the business at all levels. Currently there was an incipient crisis caused by proposals aimed at meeting the falling level of demand for Perfecta products in the present period of recession. To deal with this with minimum fuss would confirm his standing both with the waverers on the Board and with I.C.E. head office.

He pressed a button on his intercom. A moment later his secretary came into the office. She was a woman of nearly forty, rather square of feature with short cropped dark brown hair beginning to be flecked with grey. She kept herself to herself and the office buzz was that she was lesbian. Her name was Bridget Dominic, but no one called her anything but Miss Dominic, including Elgood, who had chosen her deliberately some years earlier, having learned the hard way that a mix of sex and secretaries leads to deadly dole.

‘Miss Dominic,’ he said. ‘Would you pop along to Personnel and check when Mr Aldermann’s taking time off this summer. Discreetly. And put an outside line through as you go.’

The woman nodded and left. She would be discreet, Elgood was sure. And discreet enough too to give him a good ten minutes in which to make his phone call. But for once she’d have been mistaken about its content.

He dialled a London number. As it rang, he examined the course of action he was contemplating and found nothing wrong with it. The phone was lifted at the other end.

‘Mr Easey?’ said Elgood. ‘Mr Raymond Easey? My name is Richard Elgood.’

At the same time on the floor below, Patrick Aldermann was opening the mail he had brought from home. A bank statement and the contents of several buff envelopes were put aside after the lightest glance, but one letter caught and held his attention.

He picked up his telephone and dialled. As with Elgood above, it was a London number. The conversation lasted several minutes. When it was finished he replaced the receiver and buzzed his secretary.

When she came in he was removing the wrapper from a packet. It seemed to contain some kind of book. Her eye took in the office mail which she had carefully opened and sorted. The piles stood untouched.

‘Mrs Jones,’ he said, ‘I’ll be away on Friday at the end of next week. Could you make a note of that? No, come to think of it, better make it Thursday and Friday.’

He had begun to peruse the printed sheets of the loosely bound volume, making quick little marks with a red pen.

Mrs Jones, not yet thirty but already maternal, said, ‘You do remember you’re taking the following Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday off, don’t you? Something about your little boy’s school.’

‘Of course. So I am.’

He smiled at her and she basked in his smile which she admitted freely to her intimates made parts of her she didn’t care to name feel tremulous.

‘I dare say they can get by without me here for another couple of days, wouldn’t you say, Mrs Jones?’ he said. ‘I dare say they can just about manage that.’

6 RIPPLES (#ulink_6c896840-cc10-5302-be6b-91d1069490d8)

(Floribunda. Free-flowering, lilac-mauve blooms, rippled petals, abundant foliage, susceptible to mildew in the fall.)

When Aldermann got home that evening, he found Daphne’s Polo occupying her side of the double garage. He examined the bright new paintwork on the bonnet and then went into the house.

Diana came running to meet him and he swung her on to his shoulders.

‘Mummy’s outside,’ she told him.

‘It’s the only place to be,’ said Aldermann seriously.

The rain had stopped earlier and the clouds had continued eastward, leaving in their wake a perfect June evening. He went through the french doors of the lounge on to the balustraded terrace where Daphne was relaxing on a garden lounger.

‘Hello,’ he said. ‘They seem to have done a good job on the car.’

‘They should do for the money. And they make you pay on the spot nowadays. No cash, no car. It’s very uncivilized.’

He frowned slightly, lifted Diana to the ground and said, ‘The rain’s brought off one or two petals, I see.’

‘Well, let them lie for a while,’ Daphne said firmly. ‘I’ll get us a drink and you can unwind from your hard day at the office.’

She went into the house and he removed his jacket, draped it over the back of a wrought-iron garden chair and sat down. Distantly the front doorbell sounded. A couple of minutes later, Daphne returned bearing a martini’d tray and accompanied by two men, or rather a man and a boy. The boy was in uniform, the man in a dark suit. Other claims to distinction were the boy’s Indian beauty and the man’s Caucasian ugliness.

‘Darling,’ said Daphne setting the tray down on the iron table which matched the chairs, ‘these gentlemen are from the police.’

Aldermann rose courteously.

‘How can I help you?’ he asked.

‘Actually, it’s me they want to see,’ said Daphne. ‘It’s about the car being vandalized. We needn’t disturb you, darling. Would you like to come back into the house, Sergeant? You did say sergeant?’

‘That’s right, ma’am. Detective-Sergeant Wield. And this is Police Cadet Singh,’ replied Wield without much enthusiasm.

Singh flashed them a white-toothed smile. Daphne had already recognized him as the boy she had seen in the market café but he had shown no sign of recognizing her. Perhaps whites all look alike to Asians, she thought.

Wield who didn’t want to be separated from Aldermann after so short an encounter was about to spin his prepared line of perhaps your husband might be able to corroborate one or two points when the man saved him the trouble by saying, ‘You won’t disturb me, darling. And I’d be interested to hear what the police are doing, and to help if possible.’

‘Very kind, sir,’ said Wield, pulling a garden chair towards him and posing his buttocks over it while he looked enquiringly at Daphne.

She let out a small sigh and sat down.

Wield followed suit. Singh remained standing till Wield nodded significantly at him, when he sat a little distance from the other three and emulated the sergeant by producing a notebook.

‘I hadn’t realized this would be a CID matter,’ said Aldermann. ‘Would you like a drink?’

‘Thank you, no, sir,’ said Wield. ‘To tell the truth, sir, CID wouldn’t normally be involved with a bit of one-off car bashing, but this is threatening to become an epidemic. Also we like an experienced officer to show our cadets the ropes in all departments of police work.’

Patrick Aldermann smiled faintly and Wield wondered if he were explaining too much. He put on his most serious dedicated look which could usually make children weep and strong men avert their gaze, but Aldermann’s cool brown eyes never flickered and the smile remained.

Wield returned his attention to the wife and said ponderously, ‘Now, ma’am. Your car is a VW Polo, registration AWG 830T. On Monday of this week you parked it in the Station Street multi-storey car park. This was at what time?’

‘Oh, nine-fifteen, something like that. I dropped my daughter off at her school and then just drove straight into town to do some shopping.’

‘In fact, you did a whole day’s shopping, is that right, ma’am? You didn’t come back to your car till after three o’clock.’

‘That’s right,’ laughed Daphne. ‘I got rather carried away.’

‘One of those expensive days the ladies give us from time to time, eh, sir?’ responded Wield, smiling at Aldermann. The invitation to a shared domestic laugh came from Wield’s lips like a pop-song from the Delphic oracle. It was an incongruity which went far deeper than his unprepossessing exterior. Sergeant Wield was, and, having never received the hypothesized conditioning treatment of a good public school education, presumed he always had been, unrepentantly homosexual. He guarded the secret from all but those few whose relationship with him depended on a knowledge of it, not because he felt guilt or shame but because he felt (a) that his business was his business, and doubted (b) that the mid-Yorkshire force was yet ready for a fairy fuzz. Occasionally he made believe that next time Dalziel growled bad-temperedly Right, Sergeant, what have you got for me? he would jump on his knee and offer him a kiss, but the golden rays of such sunny fancies never touched the pits and promontories of his no-man’s-land of a face.

Aldermann affected to take the remark seriously, saying, ‘If it were one of those days, Sergeant, I haven’t seen the results yet.’

‘Window-shopping mainly, was it?’ laughed Wield. ‘No harm done then. Except to your car. When you got back you found it had been badly scratched?’

He glanced at his notebook which he held close to his face in the palm of his hand to conceal the fact that it was his diary and almost empty.

‘And you immediately reported this to the police,’ he continued, as a statement not a question, but Daphne replied carefully. ‘The police were already there. Someone else had found their car damaged and reported it.’

‘Yes, of course,’ agreed Wield glancing at the diary again. ‘Now, when you parked the car that morning, did you see anything odd? Anyone hanging about for instance.’

‘No, no one,’ she said.

Aldermann said, ‘It’s hardly likely that these vandals would already have been lurking at nine-fifteen A.M., is it, Sergeant?’

His tone was one of polite enquiry.

Wield looked once more at his diary which contained nothing more helpful than the information that the following Sunday was the 2nd after Trinity, 3rd after Pentecost and Father’s Day. He said, ‘We’re not yet sure of the time the damage was actually done, sir.’

‘But surely there have to be limits?’ pursued Aldermann. ‘Between the latest time of parking of a subsequently damaged car and the earliest time of complaint, for instance. Unless this lunatic was picking them off one by one throughout the day.’

‘Well, that’s always a possibility, sir,’ said Wield as if the suggestion had been seriously intended. ‘Were there many other cars about when you parked, ma’am?’

‘Hardly any,’ said Daphne promptly.

‘No? Of course, you were parked on the roof, weren’t you? The first couple of floors fill up pretty quick with business people, I suppose. But there must still have been a lot of room on the next four floors at nine-fifteen.’