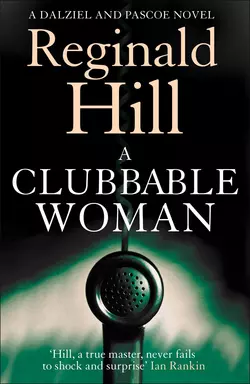

A Clubbable Woman

Reginald Hill

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 458.46 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ‘So far out in front that he need not bother looking over his shoulder’ Sunday TelegraphDetective Superintendent Andy Dalziel investigates murder close to home in this first crime novel featuring the much-loved detective team of Dalziel and Pascoe.Home from the Rugby club after taking a nasty knock in a match, Sam Connon finds his wife more uncommunicative than usual. After passing out on his bed for a few hours, he comes downstairs to discover communication has been cut off forever – by a hole in the middle of her forehead.Andy Dalziel, a long-standing member of the club, wants to run the murder investigation along his own lines. But DS Peter Pascoe’s loyalties lie elsewhere and he has quite different ideas about how the case should proceed.