A Foreign Field

Ben Macintyre

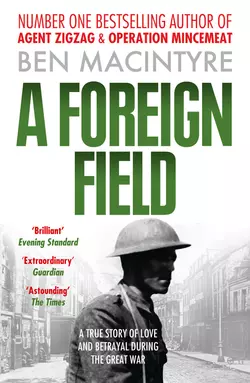

This edition does not include illustrations.A wartime romance, survival saga and murder mystery set in rural France during the First World War. From the Number 1 bestselling author of ‘Agent ZigZag’ and ‘Operation Mincemeat’.Four young British soldiers find themselves trapped behind enemy lines at the height of the fighting on the Western Front in August 1914. Unable to get back to their units, they shelter in the tiny French village of Villeret, where they are fed, clothed and protected by the villagers, including the local matriarch Madame Dessenne, the baker and his wife.The self-styled leader of the band of fugitives, Private Robert Digby, falls in love with the 20-year-old daughter of one of his protectors, and in November 1915 she gives birth to a baby girl. The child is just six months old when someone betrays the men to the Germans. They are captured, tried as spies and summarily condemned to death.Using the testimonies of the daughter, the villagers, detailed town hall records and, most movingly, the soldiers’ last letters, Ben Macintyre reconstructs an extraordinary story of love, duplicity and shame – ultimately seeking to discover through decades of village rumour the answer to the question, ‘Who betrayed Private Digby and his men?’ In this new updated edition the mystery is finally solved.This edition does not include illustrations.

A FOREIGN FIELD

A True Story of Love and Betrayal in the Great War

BEN MACINTYRE

In memory of Angus Macintyre

Table of Contents

Title Page (#ub03dcaba-ea2a-576c-a990-cdf8a7445957)

Note on Sources (#uade8e12d-8af2-514e-b256-385bde4a86bc)

Prologue (#u1bc5c891-f5dc-50cc-be34-ecf621a6ebc9)

Chapter One - The Angels of Mons (#u10a42462-6543-5ca5-b82c-c733f3c7cfa4)

Chapter Two - Villeret, 1914 (#ue38bd6d2-17c1-5895-b526-60e2078ea8d5)

Chapter Three - Born to the Smell of Gunpowder (#u56ddc4ed-fe91-5a8d-9196-7e6a2834274d)

Chapter Four - Fugitives (#u37bf4519-6220-5be2-867d-be97c4de93dd)

Chapter Five - Behind the Trenches (#u418300bd-c2e6-5ea9-84f7-34475e0c28b5)

Chapter Six - Battle Lines (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven - Rendezvous (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight - Aren’t Those Things Flowers? (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine - Sparks of Life (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten - The Englishman’s Daughter (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven - Brave British Soldier (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve - Remember Me (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen - The Somme (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen - The Wasteland (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen - Villeret, 1930 (#litres_trial_promo)

EPILOGUE - Villert, 1999 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Select Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Note on Sources (#ulink_2cbadc95-a474-51b2-b014-bf0b9cdf04d3)

This is a true story. It is based on official documents, letters, diaries, newspaper articles and contemporary writings by the participants. It would have been impossible to tell without the admirable, and peculiarly French, habit of bureaucratic history-hoarding, which prompted local officials to amass quantities of first-hand evidence from ordinary people, describing their experiences in the region behind the lines between 1914 and 1918. This information, collected immediately after the war, was carefully stored in municipal, departmental and academic archives and then almost entirely forgotten.

The story has also emerged from hundreds of hours of conversation with scores of people who were directly touched by the events described, or who learned of them from their parents, grandparents and neighbours. Their accounts are inevitably partial, in every sense, but also surprisingly consistent. Recollections of a remote time can never be perfectly accurate, but they were offered with simple honesty and I have tried to record them faithfully. What follows, then, is partly an excavation from a distant war, but also a collective memoir of a community, an attempt to reconstruct a forgotten fragment of the past through reminiscence and oral history.

Prologue (#ulink_5dd17a4a-068e-5551-9403-c60798e1de88)

The glutinous mud of Picardy caked on my shoe-soles like mortar, and damp seeped into my socks as the rain spilled from an ashen sky. In a patch of cow-trodden pasture beside the little town of Le Câtelet we stared out from beneath a canopy of umbrellas at a pitted chalk rampart, the ivystrangled remnant of a vast medieval castle, to which a small plaque had been nailed: ‘Ici ont été fusillés quatre soldats Britanniques.’ Four British soldiers were executed by firing squad on this spot. The band from the local mental institution played ‘God Save the Queen’, excruciatingly, and then someone clicked on a boom box and out crackled a reedy tape-recording of French schoolchildren reciting Wilfred Owen’s ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’.

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

Only the stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle

Can patter out their hasty orisons.

An honour guard of three old men, dressed in ragged replica First World War uniforms – one English, one Scottish, one French – clutched their toy rifles and looked stern, as the drizzle dripped off their moustaches. A pair of passing cattle stopped on their way to milking and stared at us.

The day before, I had received a call from the local schoolmaster at The Times’s offices in Paris: ‘It would mean a great deal to the village to have a representative of your newspaper present when we unveil the plaque,’ he said. I had hesitated, fumbling for the polite French excuse, but the voice was pressing. ‘You must come, you will find it interesting.’

Reluctantly I set off from Paris, driving up the Autoroute du Nord past signposts – Amiens, Albert, Arras – recalling the First World War, the war to end all wars, and the very worst war, until the one that came after. Following the teacher’s precise directions, I turned off towards Saint-Quentin, across the line of the Western Front, over the River Somme, through land that had once been no-man’s and headed east along a bullet-straight Roman road into the battlefields of the war’s grand finale. No place on earth has been so indelibly brutalised by conflict. The war is still gouged into the landscape, its path traced by the ugly brick houses and uniform churches thrown together with cheap cement and Chinese labour in 1919. It is written in the shape of unexploded shells unearthed with every fresh ploughing and tossed on to the roadside, and in the cemeteries, battalions of dead marching across the fields of northern France in perfect regimental order.

Early for my meeting with the schoolteacher, I stopped beside the British graveyard at Vadancourt and wandered among the neat Commonwealth War Graves headstones with their stock, understated laments for the multitudinous dead: some known, some unknown, and the briskly facile ‘Known Unto God’, one of the many official formulations for engraved grief worked up by Rudyard Kipling. The cemetery is a small one, just a few hundred headstones, a fraction of the 720,000 British soldiers slain, who in turn made up barely one tenth of the carnage of that barbaric war, fought by highly civilised nations for no clear ideological reason.

The schoolteacher, solemn of manner and strongly redolent of lunchtime garlic, was waiting for me by the Croix d’Or restaurant in Le Câtelet, where a group of about thirty people huddled under the eaves, like damp pigeons. I was introduced as ‘Monsieur, le rédacteur du Times,’ an exaggeration of my position that made me suspect he had forgotten my name. My general greeting to the assembled was met with unsmiling curiosity, and again I wondered why I had come to a ceremony for four entirely obscure soldiers, a tiny droplet in the wave of war blood, Known Unto Nobody.

The asylum band, set up in the field behind the restaurant, now broke into a hearty, rhythm-defying rendition of something French and appropriately martial. The three amateur soldiers came to attention, of sorts, as two cars pulled up. Out of the first emerged the mayor of Le Câtelet, the préfet of the region, and his wife; from the second an elderly white-haired woman was extracted, placed in a wheelchair, and trundled across the field to the rampart wall.

After a round of formal French handshaking, the ceremony began. The previous year I had reported on the eightieth anniversary of the Battle of the Somme, a huge, poppy-packed performance with big bands and bigwigs to celebrate the very few, very old survivors. The Le Câtelet ceremony felt somehow more apt: ill-fitting uniforms on civilians, children reciting English words they did not understand, a handful of people remembering to remember in the pouring rain. I began to feel moved, in spite of myself. The préfet launched into a lofty speech about valour, honour and death. ‘See the holes in the wall?’ the teacher whispered with a gust of garlic in my ear. ‘Those are from the execution.’ As the oration rumbled on I surveyed the crowd, few under the age of seventy and some plainly as old as the event we were here to remember. Lined, peasant faces, listened hard to the official version of what the war had meant.

Suddenly I had the sensation of being watched myself. The old woman in the wheelchair, placed alongside the préfet, had also stopped listening and was staring at me. Disconcerted, I forced a smile, and tried to feign absorption in the speech, but when I sneaked a sideways glance I found her eyes were still fixed on me. Finally the préfet wound down and the village priest offered a hasty orison, again in English: ‘Our Father who art in Heaven …’ The rain stopped, the band struck up, and the military trio shouldered their plastic and marched briskly off down the street towards the town hall, where a vin d’honneur was on offer.

As the crowd drifted away, I looked around for the old woman, and then realised she was beside me, looking up. Before I could volunteer my name she spoke, in a high, faint voice and a thick Picardy accent that I could barely understand. ‘You are the Englishman,’ she said. It was not a question. The eyes that had caught my attention were now exploring my face. They were the most intensely blue eyes I had ever seen. Unnerved again, I offered a banal observation about the improvement in the weather, but she barely allowed me to finish before piping up once more.

‘Our village, Villeret,’ she gestured vaguely to the west with a mottled white hand, ‘was over there, near the front line, on the German side. When the British were retreating, in Quatorze, some soldiers were left behind and could not get back to their army across the trenches. They came to us for protection. We bandaged their wounds, fed them and we hid them from the Germans. We concealed them in our village.’

Her voice was rhythmical, as if reciting a story rehearsed by heart and scored in memory. ‘There were seven of them, brave British soldiers, and my family and the other villagers, we kept them safe. Then, one day, the Germans came to their hiding place.’ The voice trailed away, and for the first time I became aware that another person was listening: I turned to find an elderly man standing behind my shoulder, an expression of undisguised alarm on his face. She pressed on, her eyes now turned to the plaque.

‘Three of the British soldiers managed to escape from Villeret, and returned to England. Four did not. We were betrayed. The Germans captured them. They shot them against that wall, and we buried them beside the church.’ She turned back to me and smiled gravely. ‘That was in 1916. I was six months old.’

She continued, as if the events she spoke of were the moments of yesterday. ‘Those seven British soldiers were our soldiers.’ She paused again, and then murmured, the faintest whisper: ‘One of them was my father.’

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_3389bd69-c6eb-5dac-ab84-5a517c8749db)

The Angels of Mons (#ulink_3389bd69-c6eb-5dac-ab84-5a517c8749db)

On a balmy evening at the end of August in the year 1914, four young soldiers of the British army – two English and two Irish – crouched in terror under a hedgerow near the Somme River in northern France, painfully adjusting to the realisation that they were profoundly and hopelessly lost, adrift in a briefly tranquil no-man’s land somewhere between their retreating comrades and the rapidly advancing German army, the largest concentration of armed men the world had ever seen.

Privates Digby, Thorpe, Donohoe and Martin were shards from an explosion, primed for years, expected by many, desired by some and detonated just six weeks earlier when a young Bosnian Serb named Gavrilo Princip pulled a revolver in a Sarajevo backstreet and mortally wounded Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the imperial throne of Austria-Hungary. The lamps were going out all over Europe, but in the small town of Villeret, deep in the Picardy countryside, the lamps were just being lit, watched, from under a hedge, by four pairs of hungry British eyes.

The four Tommies, of whom the oldest was only thirty-six, had barely a clue as to their whereabouts, but knew well enough that they were not supposed to be there. According to official military strategy, the men should have been at least one hundred miles north, in Belgium, winning a swift and decisive victory against the Hun. But then the war was not going according to plan: neither the Schlieffen Plan, dreamt up by a dead German aristocrat, to encircle France rapidly from the north; nor France’s Plan XVII, which called for the gallant French soldiery to attack the enemy with such élan that the Germans would immediately lose heart; nor the British plan, to defend Belgian neutrality, support the French, reinforce the might of the British Empire and then go home.

Barely a fortnight earlier, the British Expeditionary Force, or BEF (this was a war that appreciated a clipped acronym), had begun crossing the Channel in troopships. They were met with beer and flowers in the August sun. Some of the soldiers were surprised, even a little disappointed, to discover they were not going to fight the French again. They swapped cap badges for kisses and then happily headed east and north towards Belgium to teach the Kaiser a lesson: 30,000 jangling horses and 80,000 men clad splendidly in khaki and self-confidence. The poet Rupert Brooke thanked God,

Who has matched us with His hour,

And caught our youth, and wakened us from sleeping,

With hand made sure, clear eye and sharpened

power …

To the east, the first of the 200,000 Frenchmen whose élan would be extinguished forever in a single summer month, lay rotting into the soil of Alsace and Lorraine. The German behemoth hurtled down through Belgium, sweeping aside the impregnable fortifications of Liège and Namur, to the great industrial plains where the unsuspecting British army was busily arranging itself into neat battalions. ‘The evening was still and wonderfully peaceful,’ recalled one British officer, scouting in advance of the main body of troops. ‘A dog was barking at some sheep. A girl was singing as she walked down the lane.’ He watched the darkness settle gently over the land. ‘Then, without a moment’s warning, with a suddenness that made us start and strain our eyes to see what our minds could not realise, we saw the whole horizon burst into flames. To the north, outlined against the sky, countless fires were burning … A chill of horror came over us.’

At Mons, above the Belgian border, on 23 August, the British were suddenly faced by a field-grey wave of three-quarters of a million Germans, crashing down from the north. At first the outnumbered British fought with calm efficiency, then determination, then desperation. For some, the fear was worse than the blood-letting. Retreating inside France, the British turned and fought again at Le Câteau three days later, leaving more dead on the battlefield than Wellington had lost at Waterloo. The retreat resumed. Sure hands now trembled, clear eyes clouded; the depleted army scrambled south in a desperate withdrawal that would last two weeks and take them to the edge of Paris.

An old Frenchwoman stood on her cottage doorstep and watched the ragged British soldiery stumbling through her village. As the mounted officer passed, she spat a livid stream of sarcasm at him: ‘You make a mistake,’ she hissed. (The young Captain would never forget the sting of it.) ‘The enemy is behind you. Are you not riding in the wrong direction?’

For 200 miles the German army pursued, looting, burning and wielding the weapons of summary massacre and collective retribution, for this was the policy of Schrecklichkeit – organised terror designed to inflict such horrific repression on the civilian population that it would never dare to resist. Hostages were shot and bayoneted, priests were executed, homes and towns were destroyed. At Louvain, in a signal act of desecration, the great library of more than 200,000 books was put to the torch. Some German soldiers were appalled at their own might. Ernst Rosenhainer, an educated and sensitive young infantry officer, was torn between exultation and repulsion as he watched civilians fleeing from their homes: ‘It was heart-rending to hear a woman beg a high-ranking officer, “Monsieur, protégez-nous!”,’ he wrote.

The local people watched in disbelief as refugees, Belgian and then French, streamed through the villages of the Somme and the Aisne, a ‘broken torrent of dusty misery’, dragging over-laden donkey and dog carts and recounting lurid tales of German brutality. Behind followed the BEF: horse-drawn ambulances with mangled wounded and long lines of exhausted and hungry soldiers, ‘an unthought-of confusion of men, guns, horses and wagons. All dead-beat, many wounded, all foot sore.’ At their backs, plumes of smoke marked the steady German advance in a spectacular frenzy of arson. An English officer turned around from a small incline to see ‘the whole valley and plain burning for miles’.

‘We must allow the enemy no rest,’ declared a German battalion commander. The British rearguard was forced to fight as it fled. Nerves frayed, bellies empty, minds warping from lack of sleep, some retreating soldiers dozed on the march while others began to see ghosts and castles along the way. Flight forged its own legends. The Angels of Mons’ were said to have been seen hovering over the retreat, the shimmering spectres of English bowmen killed at Agincourt five hundred years earlier, now resurrected to protect their fleeing countrymen.

The Times correspondent wrote: Amongst all the straggling units that I have seen, flotsam and jetsam in the fiercest fight in history, I saw fear in no man’s face. It was a retreating and broken army, but it was not an army of hunted men … Our losses are very great. I have seen the broken bits of many regiments.’ The lines stretched and snapped; authority dimmed, the stragglers multiplied, and the treasured distinctions of regiment and division blurred as units fragmented, re-formed, or broke away. Whatever the British reading public might have been told, most soldiers were terrified. When the horses were allowed to rest, their legs folded. Unable to march further, some men threw away their equipment and lay down to die or await the enemy. Officers who would have shot any man who acted thus a day or two earlier, did not now look back. ‘That pained look in the troubled eyes of those who fell by the way will not easily be forgotten by those who saw it. That look imposed by circumstances on spent men seemed to demand all forgiveness from officers and comrades alike, as it conveyed a helpless and dumb farewell to arms.’ The neat martial logic of the army as it had disembarked on the coast of France became hazy in retreat. Most men marched unquestioningly on. Some deserted. Some looted. Some hid. Others died of exhaustion. An officer of the Royal Fusiliers recalled a private from Hackney, ‘a most extraordinarily ugly little man in my company who could not march one bit … On the second day of the Retreat he collapsed at the side of the road and died in my arms. I have no record of his name, but as a feat of endurance and courage I cannot name his equal.’

A general noted sternly that a ‘good many cases of unnecessary straggling and looting have taken place’, and summary court martials were held. Some could not resist the lure of an empty home as a hiding place or a source of plunder, and hunger saw soldiers pulling chocolate rations from the pockets of dead men or chewing raw roots scrabbled from the fields. In Saint-Quentin, two senior British officers looked on their beaten men and agreed with the petrified city mayor that surrender would be preferable to a losing fight and the probable death of countless civilians in the crossfire. It was a most humane decision, for which both officers were immediately cashiered and disgraced.

Later, the Retreat from Mons would be rendered into history as a courageous action that had held up the Germans for long enough to ruin Field Marshal Schlieffen’s plan, ensuring that the advance would finally be stopped on the line of the River Marne. But to those who took part in it, the retreat was a grim shambles, just a few shades short of a rout, ‘a perfect débâcle’. The BEF had been severely wounded. (Most of those who survived the retreat would be hacked up at Ypres a few months later). Of the 80,000 British men who had come to France to partake in a short and decisive victory, 20,000 were either killed, wounded, captured, or found to be missing on the long retreat from Mons.

In the wake of the limping army, like the detritus from some huge and surreal travelling fair, lay packs, greatcoats, limbs, canteens, makeshift graves, horse carcasses and living men. In woods, ditches, homes and haylofts, alone and in small bands, surviving shreds of the khaki army felt the battle roll over them, and then heard it rumble south. The war correspondents of the Daily Mail and The Times observed the drooping tail of the retreat: ‘We saw no organised bodies of troops, but we met and talked to many fugitives in twos and threes, who had lost their units in disorderly retreat and for the most part had no idea where they were.’

The advancing German troops were thorough in flushing out the enemy remnants: Walter Bloem, novelist, drama critic, and a captain in the Brandenburg Grenadiers, recalled how advancing German hussars, rightly suspecting that British soldiers were hiding among the newly cut corn, ‘did not trouble to ransack every stook, but simply found that by galloping in threes or fours through a field shouting, and with lowered lances spiking a stook here and there, anyone hiding in them anywhere in the field surrendered’.

Some of the more resourceful residue contrived to fight, wriggle or wrench their way out. A band of Irishmen made it to Boulogne, and at one point stragglers headed west in such numbers that German intelligence was briefly confused into believing that the British army was making for the coastal ports. Bernard Montgomery and a small group of men from various regiments marched for three days between the marauding advance guard of German cavalry and the main infantry body. Montgomery finally outflanked the advance, linked up with the rest of the army, and went on to become Field-Marshal Montgomery of Alamein.

The BEF was a regular army, an army of professionals very different from Kitchener’s volunteer force that would follow. Here were the ‘Old Contemptibles’, recruits from the industrial slums of the north, illiterate farm boys, some ‘scallywags and minor adventurers’, men who were escaping trouble and a few who were looking for it. But unlike the conscript armies of Europe, they were experienced and well-trained: some had fought in the Boer War, and most were ‘adept in musketry, night operations and habits of concealment, matters about which the other belligerents had scarcely troubled’. For many who found themselves lost in what was now enemy territory, concealment was the first instinct. When the army finally caught its breath, about-faced and fought its way north again, sceptical commanders were not always easily persuaded that the men who emerged from barns and bushes were genuine stragglers rather than deserters. ‘It was the coward’s chance,’ thought one war correspondent. ‘Was it any wonder that some of these young men who had laughed on the way to Waterloo station, and held their heads high in the admiring gaze of London crowds, sure of their own heroism, slunk now into the backyards of French farmhouses, hid behind hedges when men in khaki passed, and told wild, incoherent tales when cornered at last by some cold-eyed officer in some town of France to which they had blundered?’

Those who never reappeared were duly recorded in the regimental files. A few months later, once the full-blown trench war of stasis was underway, their families received a letter, no different from the hundreds of thousands to follow, communicating the news, with official sadness, that a husband, son or brother was missing. Yet there were some who were neither dead nor captive.

At dawn on 26 August 1914, Robert Digby, Private No. 9368, and his comrades in the Hampshire Regiment trained their rifles across the clover and beet fields north of the small town of Haucourt, and waited for the enemy. The offensive of Le Câteau had begun. As the day brightened the sound of shelling grew steadily louder. In the darkness of the night before battle, an officer had read aloud passages from Sir Walter Scott’s poem ‘Marmion’, a thumping epic full of appropriate granite-hewn sentiment.

Where shall the traitor rest,

He, the deceiver,

Who could win maiden’s breast,

Ruin, and leave her?

In the lost battle,

Borne down by the flying,

Where mingles war’s rattle

With groans of the dying.

And when the mountain sound I heard

Which bids us be for storm prepar’d

The distant rustling of his wings,

As up his force the tempest brings.

At nine in the morning, the attack finally began, and the officers of the Hampshire Regiment had ‘the pleasure of seeing Germans coming forward in large masses’. Under cover, a handful of Gennans crept up to the Hampshires’ position and shouted ‘Retreat!’, in English. It all still seemed to be a public school game. British snipers tried to pick off the machine-gun crews and officers, distinguishable by their swords. Heavy fire was exchanged and then, inexplicably, the guns on both sides fell quiet. ‘The stillness was remarkable; even the birds were silent, as if overawed.’ Just as suddenly, the battle resumed with deafening violence. Grey troops rushed across the clover, and it was ‘as if every gun and rifle in the German army had opened fire’. Too late, the order was given for the Hampshires to withdraw. Seizing rifle and pack, Private Digby joined the throng fleeing down narrow lanes. As dusk gathered, the chaos spread. ‘We marvellously escaped annihilation,’ Private Frank Pattenden wrote in his diary. ‘It was nearly wholesale rout and slaughter.’ Lurching south, the regiment began to dissolve, mixing with other fragments of the disintegrating rump of the British army. At nightfall, a small contingent of 300 Hampshires briefly held on in the village of Ligny, but then fell back once more, leaving behind dozens of injured men in a temporary dressing station. The walking wounded made their way into the woods, and the remainder waited in the darkness.

The Hampshires tramped on through the night across fields, snatching two hours’ sleep beneath a hedgerow. In the morning they stumbled into the village of Villers-Outréaux, where a German battery awaited them, having leap-frogged the retreating British in the dark. It opened up when the Hampshires were a hundred yards away. A force of fifty men under Colonel Jackson was left to provide cover, and fought dismounted German cavalry and cyclists with rifle and bayonet as the main body of troops scrambled away. Jackson was shot in the legs and carried into the home of the local curé, where he was captured a few hours later. Private Pattenden, struggling south on bleeding feet, noted the gaps in the ranks and the many missing men: ‘I am too full for words or speech and feel paralysed as this affair is now turning into a horrible slaughter … my God it is heart breaking … we have no good officers left, our NCOs are useless as women, our nerves are all shattered and we don’t know what the end will be. Death is on every side.’ The tall figure of Private Robert Digby was last seen by his comrades clutching a bloodied arm in the temporary dressing station in Ligny. A German bullet had passed through his left forearm, narrowly missing the bone, a debilitating ‘Blighty wound’ – the sort of injury that was survivable but deemed serious enough to warrant a passage home – that men would later long for in the trenches.

When Robert Digby re-emerged from the surgeon’s tent, his arm hastily bandaged and held in a rough sling, he was no longer part of a moving mass of men, but alone. ‘I lost my army,’ he would later observe ruefully. He had also lost his Lee Enfield rifle, his bayonet, 120 rounds of ammunition, his peaked cap, his knapsack, and his bearings.

Captain Williams, the surgeon of the Hampshire Regiment, was tending the wounded when the Germans stormed into Ligny. But by then Digby had taken solitary flight. A final, brief and unemotional entry in British military records concludes his official contribution to the Great War: ‘Private Robert Digby, Wounded: 26th August, 1914.’

The previous day, William Thorpe, a tubby and genial soldier of the King’s Own Lancaster Regiment, had been sitting down to breakfast in the corn stubble above Haucourt when his war started. Thorpe and the other men were tired, having marched for three days to meet the advancing German forces, but their spirits were high. ‘The weather was perfect,’ noted one of Willie’s officers, and even the spectacle of Belgian refugees fleeing south, as ‘dense as the crowd from a race meeting but absolutely silent’, had not much dampened the mood as the King’s Own marched from the railhead. The soldiers whooped at a reconnaissance plane flying overhead, which came under ragged fire from somewhere in the rear, although Captain Higgins declared the aircraft to be British.

Lieutenant Colonel Dykes had led the column of twenty-six officers and 974 other ranks past a tiny church north of Haucourt, down a gentle slope to a stream, and then up a steep hill to a plateau on the extreme right of the British line, before he gave the order to rest. ‘A full 7 to 10 minutes was spent admonishing the troops when it was found that some had piled their weapons out of alignment.’ The time might have been better spent looking at the horizon. An hour earlier the troops had been ‘greatly reassured’, although amazed, by the sight of a French cavalry unit, clad in their remarkable plumes, breastplates, and helmets: handsome and conspicuous imperial anachronisms. Since the French advance guard was supposed to be out ahead of the British troops, an officer declared that the enemy ‘could not possibly worry us for at least three hours’. This was, therefore, an excellent moment to eat breakfast.

As they waited for the mess cart to arrive, the officers observed another group of uniformed horsemen some 500 yards away, which paused to watch the relaxing troops before trotting away. One of the younger officers quietly suggested that the cavalrymen might not be French, and was sharply told ‘not to talk nonsense’. The men were lounging and talking in groups in the quiet cornfield; the sun was growing warm when the mess cart finally rumbled up. On top of the wagon perched the regimental mascot, a small white fox terrier, clad in a patriotic Union Jack coat, that had been adopted before leaving Southampton. ‘New life came to the men’, who leapt to their feet, mess tins at the ready.

At that moment the German Maxim guns opened up. Colonel Dykes was killed in the first burst, shot daintily through the eye, his groom making ‘a valiant attempt to hold his horse until it also was killed’. ‘Some tried to reach the valley behind,’ but the older and cannier soldiers lay flat on their faces and hugged the earth, as the bullets flicked the tops of the cut corn stalks. ‘Of those who got up, most were hit.’ After two minutes of uninterrupted firing, the German gunners paused to reload and the survivors scrambled for cover below the crest of the hill. For the next five hours, what remained of the regiment was pounded with shells. Through field glasses, the future Field Marshal Montgomery observed the ‘terrible sight’ and then followed orders to try to help the trapped Lancasters. ‘There was no reconnaissance, no plan, no covering fire. We rushed up the hill.’ With predictable results. This was ‘terrible work as we had to advance through a hail of bullets from rifles and machine guns and through a perfect storm of shrapnel fire. Our men … were knocked down like ninepins.’

Many of the wounded were too badly injured to be moved, and by late afternoon, when the order came to fall back, the King’s Own Lancasters had been torn apart. Haucourt church was packed with bleeding and dying men, while dazed pockets of survivors, separated in the panic, wandered in search of their commanding officers and orders. A day that had started in perfect calm ended in utter confusion, as what was left of the King’s Own joined the great retreat. ‘There was nothing to do for it but to leave the wounded and hope that any stragglers would rejoin,’ one officer said. When the battalion was finally able to draw breath, the losses seemed barely believable: fourteen officers and 431 other ranks killed, wounded or missing, along with the mess cart, commanding officer, two machine guns and the fox terrier. (The distraught driver of the mess wagon was found to be carrying the dead dog under his shirt the next day, and was sharply ordered to bury it.) In three hours of battle, the King’s Own Lancaster Regiment had lost half its strength and much of its morale. It had also lost Private William Thorpe.

David Martin, Thomas Donohoe and the Royal Irish Fusiliers had arrived in France in typically jovial fashion, ‘singing and cheering and chanting the regiment’s motto, Faugh-a-Ballagh, “Clear the Way”.’ The local French civilians found the Irishmen intriguingly odd, and the curiosity was mutual. During a reconnoitre to the east, one officer from the Irish regiment was taken prisoner by an over-enthusiastic French commander who evidently suspected that he had come across a German spy posing as an Allied soldier. He also seems to have had some peculiar notions about the distinguishing anatomical features of a British officer, for he told his astonished captive: ‘Although I am sure you are what you say you are, still these are unusual times and perhaps you would not mind undressing, and giving me some proof that you are English.’ The officer huffily refused to demonstrate his nationality thus, and sadly we will never know what the Frenchman hoped to find that would have convinced him.

Like the King’s Own Lancasters and the Hampshire Regiment, the Irish Fusiliers were positioned close to Haucourt, just south of the village. By mid-morning on 27 August, the regiment was locked in a ferocious artillery duel. ‘Outnumbered and outranged,’ the Irish troops fell back shortly before nightfall and by the early hours of the next day the battalion, one of the last regiments to vacate the position, was in headlong retreat, but still displaying a jollity that astonished the regimental interpreter: ‘I do not understand you Irish,’ he said. ‘We Frenchmen are glad when we go forward but sad when we come back; you Irish are always the same, you always laugh and all you want is bully beef.’

The laughter swiftly subsided as the withdrawal turned into a continuous forced march, often under attack from the rear. The day grew hot and humid, but there was no pause. Slogging along grimly ‘as if in a trance’, the men stripped off their packs and threw them by the roadside. As the twenty-fourth hour of non-stop marching approached, some were left ‘with only the remains of boots’. Others collapsed, ‘physically unable to march further without rest’, but there was no time to wait for them to recover, nor was there the means to move them. The brigade commander pressed on, noting that ‘to our rear the lurid glare of burning farms and haystacks shed a fitful light on the scene’. On the evening of 28 August the exhausted Irish troops crossed the Somme River, just before the bridge was blown up, and were able to rejoin the British rearguard. When the muster roll was called, 136 men and officers were found to be missing, including Privates Thomas Donohoe and David Martin.

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_c7af61d4-3999-59fc-a30f-cc9ce1b3447d)

Villeret, 1914 (#ulink_c7af61d4-3999-59fc-a30f-cc9ce1b3447d)

South of the cornfield battlefields lay Villeret, a small village of simple brick houses with roofs of slate, tile and thatch, tucked into the folds of the Picardy countryside. A wayfarer stumbling upon Villeret by chance in 1914 – and few strangers ever came through save by accident, since Villeret was not on the way to anywhere – might have paused to take in the picturesque view from the hill above the village, for as one traveller observed, ‘nature is beautiful around Villeret, and the poet or painter might stop here to depict the scene, one in the harmonious language of verse, the other by fixing the scene on his canvas’. The wanderer might also have stopped for a restorative drink, perhaps a glass of genièvre, the ferocious local gin, in the café on the corner: an establishment called ‘Aux Deux Entêtés’, the two hard-heads, with a sign showing two asses pulling stubbornly in opposite directions. Or he might have halted to observe the modest tombs in the undistinguished church, or to admire the well-kept rose garden in front of the girls’ school, the pride of the young schoolmistress, Antoinette Foulon. He might have inquired what great personage lived in the ornate, still-new château on the hill. But since he would most likely have been lost, he would have tarried just long enough to obtain directions before hurrying on to the larger settlement of Hargicourt, just across the valley, or to the ruined fortress at Le Câtelet, the most important town in the canton, five miles to the north on the road between Cambrai and Saint-Quentin.

Villeret moved to a rhythm and pattern as immutable and familiar as the motifs in the cloth woven down the centuries by its villagers. Here Léon Lelong baked his bread to a recipe bequeathed by the ancients; women in wooden clogs drew water from a pump in the cobbled square; and looms rattled in every cellar, reaching a crescendo at dusk and then slowly fading into the night, the steady clanking heartbeat of a Picardy village.

That August Villeret appeared, at least on its homely surface, to be following its regular ambling course, as contented as the pig lounging in the shade of butcher Cardon’s house. But a glance inside the door of the mairie, a grand two-storey structure with the unmistakable pomposity of French municipal architecture, might have offered a rather different impression. For in the summer of 1914 Villeret was on a war footing, its elders in a state of unprecedented anxiety. Of the approaching German army, and the carnage it had wrought, Villeret knew almost nothing. But the war had already jolted village life out of kilter, and Camille ‘Parfait’ Marié, the acting mayor of Villeret, was having to put his mind to a problem not encountered by the village since the Prussians had marched into northern France forty-four years previously: with so many men already summoned into uniform, there would be barely enough hands to bring in the harvest, which was late this year as it was. (At the same time, across the Channel, the conflict in Europe was impinging on normal existence in a similarly upsetting fashion. On 4 August, the Catford Journal reported: ‘What with the war and the rain, last Saturday was a most depressing day for the Catford Cricket Club.’)

War had officially begun in Villeret at exactly five o’clock on the afternoon of 1 August, when Le Câtelet’s garde champêtre, or municipal policeman, marched portentously up rue d’En-Bas, clanging his bell to announce mobilisation. Some of the boys had been so anxious to get into battle they had dropped their tools in the fields. Within a few hours of hasty farewells the village population of roughly 600 had shrunk by more than a third. Even the mayor, Edouard Severin, rushed off to war, leaving his deputy in charge. Thrust into a position of uninvited responsibility, Marié, a charcoal-maker with drooping moustaches, thick spectacles, and a permanently unhappy mien, quickly found the weight of office burdensome. The acting mayor was universally known as ‘Parfait’, which happened to be his middle name, but which also aptly reflected his cast of mind: he was a perfectionist, albeit a constantly frustrated one, and missives from the préfecture at Saint-Quentin had begun arriving on his desk in swift and baffling succession.

On 5 August the sous-préfet demanded: ‘How many workers are needed to bring in the harvest? Please reply as soon as possible and before midday tomorrow.’ Then someone calling himself the ‘President of the Food Commission’ wanted to know exactly how much wheat, dry and ground, was immediately available. Next, with powerful oddness, it was decreed that all street advertising for Bouillon Kub, a variety of powdered broth, should be torn down. German spies were suspected of leaving a trail of messages on such hoardings for the use of advancing troops, but since Marié could not possibly have known this, the request must have seemed, to say the least, eccentric.

A little over a week later another impossible order landed on Marie’s desk – ‘Extend help to all needy English, Belgian, Russian or Serb families.’

There were no such families in Villeret, for even by the standards of rural northern France the community was an isolated and self-contained one. Even the inhabitants of Hargicourt, just a quarter of a mile away, were considered ‘foreigners’ by the Villeret folk, and regarded with abiding distrust. In turn, the people of Villeret were often dismissed by neighbouring communities as a collection of ‘gypsies’, backward peasants who kept to themselves. There was a local saying: ‘The rich folk of Hargicourt, the clever folk of Nauroy and the savages of Villeret.’ Like that of many villages in Picardy, the social structure of Villeret was founded on an interrelated network of clans, families linked by blood, marriage and feuds. For as long as anyone could remember, Villeret had been home to the Mariés, the Cornailles, the Morelles, the Dessennes, the Foulons and the Lelongs – united by a common distrust of the world beyond the village boundary. Few Villeret villagers spent much time in Hargicourt or Le Câtelet, and only rarely would they travel the eight miles to the market town of Saint-Quentin, for the rest of France was a fickle place, important as a market for beet, wheat and brightly coloured cloth, but otherwise to be avoided. Villeret was not unique in this philosophy. One of the region’s historians described his fellow Picards as ‘frank and united, rarely keen to leave their land, living on little, sincere, loyal, free, brusque, attached to their opinions, firm in their resolution’. An old Picardy saying aptly captures the Villeret attitude, lying somewhere between selfishness and self-reliance: ‘Chacun s’n pen, chacun s’n erin’ (Chacun à son pain, chacun à son hareng), each has his own bread, each his own herring. In other words, mind your own business.

Many of Villeret’s inhabitants had multiple businesses: weaving, seasonal farming, occasional manual labour, perhaps a little tobacco-dealing or a café on the side. Alphonse Morelle, for example, called himself a weaver by trade, but explained: ‘Before the war I had a café and sold some tobacco, but in between times, at home, I did some weaving, and in the summer I hoed the beets and helped with the harvest.’

Some of the Villeret men worked in the Templeux-le-Guérard phosphate mine beyond Hargicourt, and although this brought in extra money, it coincidentally tended to compound the village reputation for anti-social behaviour. Inhaled phosphate dust had left many mine workers with damaged lungs, which were often treated only with copious quantities of blanche, a white liqueur similar to absinthe. The drink dulled the pain but, like absinthe, it also destroyed the mind, and there were at least forty people in Villeret with brain damage resulting from addiction to this poisonous brew. In 1914 the village contained no fewer than thirty ‘cafés’. Some of these were little more than cellars with a single barrel, while others were almost luxurious. The ‘Aux Deux Entêtés’ offered a billiards table, wind-up gramophone with a choice of sixty records, and an archery gallery, as well as a multitude of different drinks, from fine champagne to the throat-roasting genièvre.

Outsiders, particularly those with claims to cultural sophistication, were inclined to see the village as a rustic throwback. A new schoolteacher, Monsieur Duchange, had arrived in 1907 to find what he called a ‘thoroughly mediocre intellectual and moral standard’, a community populated by thieves and drunks, riven by internal bickering and run by a mayor who was corrupt, oppressive, and violent. Duchange left after three years, declaring he ‘would not want to stay a moment longer in such a place’. What the scandalised schoolteacher failed to appreciate was the other side of the Villeret character: a streak of hardy independence that could easily be taken for ignorant belligerence, unless it was on your side. Villeret was an easy place to miss, an easy place to disdain, but as the Kaiser was about to discover, it was not an easy place to subdue.

With the war approaching, the first wisps of fear, gossip, information and disinformation began to blow through the region, even reaching the isolated enclave of Villeret. Rumour insisted that German spies were in the area posing as Swiss mechanics repairing the looms. Two optimistic volunteers with a single gun and two cartridges set up a guard post on the road into Le Câtelet, and hung a chain across the road to hold back the German army. Some of the better-informed inhabitants made preparations to leave.

On 16 August, four days after the first troops of the British Expeditionary Force crossed the Channel, the locals had their first glimpse of an Englishman in uniform, in the form of an affable fellow on a motorcycle. With the schoolmistress of Le Câtelet translating, he managed to explain that he had been following an air squadron and was trying to get to Brussels. The villagers pointed to the north and before heading off the motorcyclist turned to survey the rolling fields as if he were a carefree tourist. His words were carefully recorded: ‘Oh, France, beautifully.’

German troops marched into Brussels four days later, but a week went by before another English soldier appeared in Villeret, this time demanding the whereabouts of the largest village shop. He was duly directed to the establishment of Alexis Morel, who was a part-time grocer, haberdasher, café-proprietor, liquor salesman, and sometime chairman of Villeret’s archery club. He also sold bread. The soldier instructed Morel to supply every loaf he had in stock to feed the advancing British army, and to prepare another batch for the following day. Morel complied without demur, but assiduously noted the cost of the requisitioned bread: ‘295 francs’.

It would be more than six years before Morel saw any reimbursement, and it swiftly became apparent that the British army, fuelled on his bread, was no longer advancing, but retreating. The first sign of the calamity was the sight of Belgian refugees, initially a trickle, but soon a torrent, moving south through Le Câtelet. ‘They had the unspeakable in their eyes; they carried their belongings and their gestures were despairing.’ The guns were now clearly audible.

Achille Poétte, the cadaverous, indefatigable postman of Villeret and chief local gossip, suddenly found himself unemployed when the postal service was abruptly terminated. That evening an exhausted squadron of French cavalrymen passed through Le Câtelet, their stumbling mounts, drawn faces, and evident lack of élan offering the first clear sign that victory had not materialised. The officer gamely insisted the retreat was merely strategic, a prelude to the flanking movement that would drive the Germans back. The people chose to believe him and when a passing refugee claimed that Walincourt, ten miles north, was already occupied, he was threatened with jail for spreading alarming news. But then came incontrovertible proof: long lines of horse-drawn ambulances carrying British wounded, and behind them columns of soldiers, their faces pallid from fatigue and fear. Ninety-five injured soldiers were treated at the makeshift hospital set up in Mademoiselle Founder d’Alincourt’s château at Le Câtelet, while the bakers’ ovens churned out extra loaves for the retreating men.

In her diary, the schoolteacher who had helped the lone English motorcyclist watched the British in retreat: ‘They had only one desire, to go faster, ever faster, to escape the enemy who, their desperate gestures seemed to say, was snapping at their heels.’ Cavalrymen rode slumped in their saddles, and infantrymen collapsed in Le Câtelet square and slept as they fell. Now the civilian exodus had begun. From Hargicourt some 300 people headed south, on foot or in wagons, and others began to seep out of Le Câtelet. ‘It is very sad to see the poor villagers flying south as we retire,’ wrote one British officer. ‘Those who, as we came north a fortnight ago, looked on us as their deliverers, are now thinking we are broken reeds. They are crying and asking us to save them and their homes … A ghastly business. Poor creatures.’

Out-of-the-way Villeret did not witness the British retreat, but the tales of what was happening in Le Câtelet, spread graphically by Poëtte, set the exodus in motion. Cardon loaded up his horse and cart with his possessions and family, and creaked off down the road to Saint-Quentin, watched by the rest of the population, and the anxious butcher. A handful of others left in the ensuing hours, but most chose to stay. The tales of German atrocities were only rumour, after all.

From the top of his monumental château on the hill above Villeret, monumental François Theillier trained his telescope to the north and saw rumour made fact. A thick column of smoke, invisible to those in the valley, was rising from the town of Caudry, just twenty miles away to the north-east. François Theillier was the nearest thing in Villeret to a feudal lord: many of the villagers worked his land, he owned an automobile with a radio in it, and he was so much wealthier than anyone else for miles around that a man who had won at cards or sold his crop well was said to be ‘as rich as a Theillier’. The family fortune had been made from the charcoal mines of Anzin, and Francois’s father, Colonel Edouard Theillier, had naturally set about building himself a château commensurate with the family’s social standing. Completed in the 1880s in a style intended to echo that of the early seventeenth century, the Château de Grand Priel dominated the skyline, a statement of unlimited money but limited taste, boasting pink granite columns, lordly turrets and exactly ninety-nine windows, since one more would have meant a higher rate of tax. The colonel’s wife, in the great tradition of the châtelaine, dabbled in fashionable forms of agriculture, installing her prize herd of Swiss cattle in stalls adorned with ‘polished brass balls’. A semaphore relay manned by retainers was set up on the roads leading up to the château, as a sort of primitive traffic light system to ensure that when any member of the Theillier family wished to be on the road, nobody else was in the way.

Old Colonel Theillier had died in 1900, leaving one son, Pierre, to manage the estate, and the other, François, to indulge his twin passions of hunting and food. The only occupation François Theillier liked more than killing animals was eating them. Large concrete drinking troughs were imported from Paris and placed at strategic points around the château to lure deer, wild boar and other game within range of Francois’s guns. Rabbits were left to breed unmolested to produce a sufficient supply for the master’s bag, even though they chewed the Theillier fields to shreds. Bred pheasants were added to the wild partridges that furnished his groaning table, and imported snails from Burgundy were farmed in vast cages, fattened to the correct size and succulence by an estate employee whose sole task was the provision of limitless gastropods for the gastronome.

François Theillier was, inevitably, enormous. Even as a child, he had been very portly and the locals joked (in an undertone) of the measures taken to try to combat his ballooning bulk: his parents were said to dangle rattles out of his reach, just to try to make him move, and the colonel was rumoured to have locked the teenage François in the cowshed to keep him out of the pantry, whereupon he was said to have eaten the cattle fodder. By the outbreak of war Theillier had reached his full, majestic corpulence, with a weight variously estimated at somewhere between twenty-eight and thirty-seven stone. ‘He had to sit on three chairs side by side,’ it was said, and while out hunting he was pulled in a large cart with a revolving seat on top and a loader stationed behind, thus enabling François to slaughter the local fauna in droves while expending a minimal amount of energy. The landowner’s preferred method was to hunt with a rifle in each hand. ‘He waited until the birds crossed in flight, and with four cartridges he could kill eight birds.’ One day, a stranger to Villeret came across François Theillier asleep under a tree at the gates to his château. The man did not stop running until he was safely back in the village. ‘I’ve just seen God the Father,’ he reported.

For such an immense man Theillier could move quite fast. And what he now saw from the château roof that August morning sent him bounding into his car (whose doors had been widened to admit him). The chauffeur was instructed to drive to Saint-Quentin as quickly as possible. The local seigneur did not trouble to stop and warn the people of Villeret of what was so dramatically bearing down on them from the horizon.

Field Marshal Sir John French, commander of the British Expeditionary Force, had made his headquarters in Theillier’s grand house on Rue Antoine Lécuyer, where a Swiss chef was the only staff member remaining. The Field Marshal arrived there just a few hours before Theillier, having been rousted out of his bath in Nauroy Château before his dinner, to be told that the Germans were at Estrées, just over a mile away. Theillier knocked on his own door and informed the Scottish guardsman who opened it that he had important information for the field marshal, only to be told that the British commander-in-chief was packing and preparing to leave Saint-Quentin. Twenty minutes later, French and his staff had gone, heading south with the rest of the BEF. Wandering into his dining room, Theillier found a package of papers ‘bearing the inscription “Secret Service” … then, moving on to the kitchen, he noticed a large pot full of freshly-chopped leeks for the dinner of the field marshal, who once again had been forced to miss his meal. The chef had a sour expression on his face.’

The ‘secret service’ papers would eventually find their way back into the hands of British intelligence; the fate of the leeks, given Theillier’s fabled appetite, is less mysterious. Having finished a supper intended, literally, for an army, Theillier heaved himself back into his car and followed the exodus south. He would never see his château again.

The same evening Theillier motored away into comfortable exile in Paris the first squad of German cavalry, the very tip of the enemy’s advance guard, entered Hargicourt in pursuit of English stragglers. Not recognising the German uniforms and believing he was welcoming English hussars, the mayor came out to offer the horsemen champagne. But the patrol of eight German dragoons led by a lieutenant did not stop, for they had spotted two men in khaki uniforms struggling on foot up the slope to Villeret. One of these was John Sligo, a thirty-year-old Welshman from the Rhondda Valley. His regiment, the Somerset Light Infantry, had come under heavy fire at Ligny and in the retreat, like many others, Sligo had been wounded and left behind. The man with him was Private Robert Digby.

In the three days since he had become separated from the Hampshire Regiment, Digby had wandered along empty country roads, moving at night and hiding by day. At the village of Gouy, which adjoins Le Câtelet, he had sought the help of the local priest, the Abbé Morelle, who rebandaged his arm. There he found John Sligo, who had also been tended by the priest, and the two fugitives had moved on together. They rested a few hours in ‘an abandoned factory’ before setting out again. Dusk was gathering as Digby entered Villeret for the first time.

The German dragoons spurred their horses. Hearing the clatter of hooves and turning to see the German patrol less than half a mile behind them, the Englishmen ran. Through the town square, past the town hall and the butcher’s, they ducked right, out into the open again, sprinting towards a dense copse some 200 yards from the edge of the village. Seconds later the German dragoons entered Villeret at a gallop, guns drawn. Digby was younger than Sligo and a keen rugby player. The Welshman may also have been more seriously wounded, for Digby reached the woods well ahead of his companion, and plunged into the thick undergrowth, just as the leading horseman caught up with Sligo, and shot him dead.

The wood was impenetrable on horseback and night was closing in. The German dragoons paused briefly at the edge of the copse to peer into the vegetation before they ‘swung around in the direction they had come’, and trotted away. As one villager later remarked: ‘It was the last pointed helmet we would see for some time.’ When it was quite dark, a handful of village men warily emerged from their homes and retrieved the body of the dead soldier from beside the place they called Les Peupliers de la Haute-Bruyère, the poplars on the high heath. Parfait Marié filled out his first death certificate, copying the Welshman’s strange-sounding name from his identity tags in immaculate curling script. That night, John Archibald Sligo was buried in an unmarked grave, the first foreign resident of Villeret’s tiny graveyard.

Robert Digby was not the only fugitive in the woods around Villeret that night. Over in the forest below the Château de Grand Priel, where François Theillier was wont to carry out his daily depredations on the local wildlife, Arthur-Daniel Bastien, a young maréchal des logis, or sergeant in the French cavalry, perched glumly on a log, still wearing his magnificent crested helmet with horsehair plume, cuirasse and spurs, ruminating on why he had been ordered into a twentieth-century battle with equipment and tactics designed for the Napoleonic era. Bastien had been trained, as he put it, in ‘hand-to-hand combat with a sabre handled at full gallop, a long lance for charging the enemy, a carbine with three cartridges and, for non-commissioned officers, a revolver’. He believed he had been ‘sent to war with methods practically the same as those employed under the Second Empire’, and, like every French cavalryman ‘schooled in the arts of war on horseback’, he had considered it his patriotic duty to charge the German army with drawn sabre at the first opportunity and drive it out of France and Belgium. Only the first part of Bastien’s plan had come to pass. Unlike the French, German cavalry units were usually accompanied by infantry with machine guns, and though the breastplate looked wonderful on parade, it was visible from miles away and it was not bullet-proof.

On 27 August, Bastien’s regiment, the 9th Dragoons, part of General Sordet’s cavalry corps, found itself at Péronne, about ten miles due west of Villeret on what would soon be the line of the Western Front, attempting to protect the left flank of the British force against the advancing Germans, but becoming utterly disorientated in the process. ‘With the Germans on our heels, and constant contact between our patrols and those of the enemy, to physical exhaustion was added the permanent nervous tension of knowing the enemy was right behind us,’ Bastien recalled. Reaching the crest of a hill east of Péronne, Bastien and his troop realised that they had strayed into the very midst of the enemy: the infantry division directly ahead was composed not of retreating British soldiers, as they had blithely assumed, but of advancing Germans. Years of training obscured any vestige of common sense, and the commanding officer, one Captain de la Baume, did not hesitate. The cavalry troop must fight its way back to the rest of the French army, he ordered, and ‘charge, without hesitation, anyone who got in the way’.

‘The dragoons made a beautiful sight as we advanced across the plain, helmets on, plumes blowing in the breeze, blue-black jackets and red trousers, arms glinting in the sun.’ The German machine gunners had plenty of time to line up their sights. ‘The lieutenant ordered the charge. Lances were lowered, the riders leaned forward and spurred into full gallop.’ Bastien’s troop broke through eight successive lines of German infantry, pausing before each fresh charge.

Here was heroism, but here, too, was mounted suicide in full dress costume. ‘The infantry scattered before us every time, but their fire decimated the squadron and the bullets whistled around my ears,’ wrote Bastien, who was positioned at the extreme right of the rapidly thinning line of horsemen. Suddenly, Bastien found himself galloping down a steep incline which brought him on to a road. No more than twenty feet away was a stationary German convoy. Bastien lowered his lance and charged once again. ‘The convoy of soldiers was kneeling and firing, and I could hear the bullets wailing around me. Thanks to God and the speed of my mount, neither I nor my horse was hit. No German cavalryman dared to confront me, and the last bullets came from behind me. The countryside ahead was empty, but the rest of the squadron had gone.’

Arthur-Daniel Bastien was one of the few survivors of one of the last great cavalry charges in history. In less than an hour, the Ist Squadron of the 9th Dragoons had been almost obliterated.

Still looking for someone to skewer, Bastien galloped on for a mile, his ‘nerves at full stretch’. Then, when the adrenaline had subsided, the Frenchman hid in a small wood, which happened to belong to François Theillier, and wondered what to do next. ‘Having thanked Providence, I tied up my sweat-soaked mount and checked I was not being followed. The wood seemed to be empty of people, with a château on one side, and on the other a forester’s cottage which appeared to be unoccupied.’ Bastien broke in through a window, took what food he could find, and left an apologetic note to the owner for this ‘forced loan’.

‘As night fell, I stretched out in the ferns, beside my horse. My sleep was agitated, the night was cold, and I woke up time and again, my teeth chattering. The next morning I tried to analyse the situation calmly.’ Bastien concluded that his best option was to head south and try to catch up with the retreating French or British armies. ‘The Germans don’t take isolated prisoners,’ he reflected, wrongly. ‘They execute, on the spot, any straggling soldiers they catch … I decided to keep my weapons and fight to the death, if necessary.’ Returning to the forester’s house, he raided the rabbit hutches behind the building and dined on ‘raw rabbit for the first time’, declaring it to be ‘quite acceptable for a starving man’. As Bastien chewed his lapin tartare, he spotted ‘three new occupants coming into the wood, who turned out to be three British infantrymen, utterly disorientated’.

Willie Thorpe of the King’s Own Lancaster Regiment had by now linked up with Donohoe and Martin of the Royal Irish Fusiliers, and all three were mortally scared, and famished. As befits a French cavalry officer, Bastien, who spoke a little English, did not forget his manners and courteously offered to share his unappetising meal: ‘I gave them a gift of the remains of the rabbit, and pointed out the general direction of the Allied troops.’ The Frenchman then bade farewell to the British soldiers: ‘I remounted, lance in hand and revolver in pocket, my sabre lying alongside my saddle, and set out in a south-westerly direction.’

Four months later, Bastien rejoined the French army, after disguising himself as a civilian, walking over a hundred miles to his home town on the Belgian border, and finally returning to unoccupied France via Holland, Folkestone and Calais. ‘I will never forget those months in 1914, the last great days of the French cavalry,’ he wrote in his memoirs. Fifty years later, Arthur-Daniel Bastien still wondered about the fate of the soldiers he had met in the woods of Château de Grand Priel by the village of Villeret.

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_e7ee6556-4751-559b-ba09-8d080a49f023)

Born to the Smell of Gunpowder (#ulink_e7ee6556-4751-559b-ba09-8d080a49f023)

Villeret sits on a small plateau at the edge of the European flatlands where English, French, Austrian, Spanish, Prussian and Russian armies have marched and fought for centuries. Memories of warfare run through the land as deeply as its rivers and thick chalk seams. To the north of the village flows the River Cologne, to the south is the Omignon, and to the east the Saint-Quentin Canal, fed by the River Escaut, all tributaries of the great Somme. Long before that name became a synonym for slaughter, war was part of the region’s very soil. The young of the village were weaned on tales of the brutal Russian soldiers, the dreaded Tartars and Kalmucks, who marched in after the Battle of Waterloo, and the older folk remembered well the Prussian siege and occupation of Saint-Quentin in 1870; the painter Henri Matisse, who grew up in the nearby weaving town of Bohain, was fourteen months old when the occupation of his home came to an end, but at every meal his mother bitterly recalled how an invading soldiery had gorged itself on France: ‘Here’s another one the Germans won’t lay their hands on.’ In the nineteenth century the schoolchildren of the region sang the songs of war:

Children of a frontier town,

Born to the smell of gunpowder.

Villeret. The very name was the legacy of a Roman invader. For this was the spot chosen as the site for his summer villa by some unnamed but ‘powerful personage’ from the Roman camp at nearby Cologna: his villa became Villaris in the tenth century, Villarel by the thirteenth and finally Villeret. Le Câtelet had once marked the northern frontier of France, and here, in 1520, François I built a great fortress, a massive, moated declaration of military muscle in brick and stone, 175 metres long and 27 metres high. The Spanish had laid ferocious siege to the citadel, and Louis XIV finally ordered the fortress abandoned, but the great edifice still stood, the village clustered around its base, its chalky face pock-marked by cannon shot and studded with flint. Beneath Villeret church, a local archaeologist uncovered the burial place of even earlier warriors, Merovingian damascene plates, belt buckles of steel inlaid with bronze, left by the knights of Clovis and then Charlemagne, while a crumbling document in Saint-Quentin attests to the martial piety of Jean, seigneur de Villeret, son of Evrard of Fonsommes, who dutifully set off for Jerusalem in the year 1193 to slay the infidel in Holy Crusade.

War, invasion and occupation forged a robustly pessimistic people ‘rude and rough, scoured by the winds from the North’, in the words of one historian. ‘The Middle Ages lived on in our midst.’ Over the years, Villeret had come to look with practised mistrust on any soldier, friend or foe. In 1576, the village even sent a letter to the King, requesting that he cease to employ foreign mercenaries to defend his realm since ‘foreigners, notably the Germans, have come through Picardy in the past, with their wagons and ravenous horses, stealing anything they can find, laying siege to the mansions and forts, raping women and girls, killing gentlemen and others in their own homes’.

Nothing, however, could have prepared Villeret, Le Câtelet, and the surrounding villages for the military Titan that descended from the north in the summer of 1914. The curé of nearby Aubencheul gazed on the massed ranks of German soldiery with a mixture of terror and admiration:

What an unforgettable spectacle! The artillery filed through: light guns, heavy cannon shining and clean, pulled by superb horses bursting with vigour, as fresh as if they had just come from the stables. On and on they came. Infantry buoyed up by their first victory, immune to fatigue. These men were like giants, their dominating stares seemed to penetrate everywhere. They sang, and cried out ‘Nach Paris! Paris dans trois jours!’ Oh, such beautiful men, robust, drunk with pride. We shall never see their like again.

But fear also coursed through the land. The villagers watched the invaders come, and later told tales of horror. In Vendhuile, to the north, Oscar Dupuis stood by as a group of German infantrymen pillaged his home and then fetched his revolver, wounding two of the looters before being shot dead. At Bellicourt, a young British soldier had been discovered hiding in a cellar by rampaging Germans in search of drink; he was tortured, it was said, by being doused in boiling water, then shot, and thrown in the canal. The people of Gouy stared as the columns of German infantry marched through the town, chanting and singing, while at Beaurevoir they shouted 𠆉Où sont les Anglais?’ and ‘looted every house, drinking wine straight from the bottles and then smashing them in the street’.

The body of Pierre Doumoutier, Villeret’s carpenter, was brought back to the village the same night, and buried alongside that of john Sligo. Doumoutier had been guarding a bridge at Joncourt as the first enemy patrols came into view. He had rapidly, and sensibly, concluded that his ancient shotgun was no match for the advancing Germans and attempted to make his way back to Villeret. But he and two other villagers stumbled into a German patrol which immediately opened fire. Doumoutier was killed, but the ‘other two managed to escape’. Some said the carpenter had been a fool to offer resistance in the first place.

In the German military mentality, the francs-tireurs of the Franco-Prussian war, irregular partisans waiting to put a bullet in German backs, still lurked behind every tree and building. Any hint of armed defiance was to be met with extreme, salutary violence.

Le Câtelet, a key strategic point on the route south to Saint-Quentin and Paris, bore the main brunt of the invasion and, when it attempted resistance, felt the full metallic lash of Schrccklicheit.

On the evening of 27 August, the last significant body of British troops had moved out of the town, leaving behind a small rearguard of seven men to try to hold up the German advance. These were, by coincidence, men of the King’s Own Lancasters, William Thorpe’s regiment, who had been sitting ‘playing cards in the estaminet, with great sang-froid’, and who then ranged themselves across the main street as the enemy cavalry came into view. A small troop of hussars advanced gingerly. ‘Only two cavalrymen continued to come forward right to the bridge, where they dismounted, about 100 metres from the six or seven Englishmen who just watched them, without moving, impassable.’

The tense stand-off might have continued indefinitely had not a troop of German dragoons burst into view at a canter from the direction of Villeret, unaware that Le Câtelet was still effectively held by the enemy. ‘The English opened fire and the German officer – an Alsatian aristocrat, we later learned, who was headed for a brilliant career – was shot dead along with his horse directly in front of the presbytery.’ The other riders dashed for cover, but noticed as they fled that gunfire was coming from another direction.

In an upper-floor window stood a man in civilian clothes, an abandoned British army cap jammed on his head, firing as fast as he could at the fleeing Germans. This was Guy Lourdel, the tax official and town clerk, who had been unable to resist joining the fray. The English soldiers, along with a handful of walking wounded who had been treated by the curé Ledieu, now scattered into the surrounding fields, leaving behind some forty men too badly injured to move. Half an hour later, the German hussars returned, accompanied in force by the 66th Infantry Regiment, to flush out the murderous franc-tireur and teach Le Câtelet a lesson. ‘Hundreds of soldiers, unleashed like wild beasts by their officers, ran everywhere, brandishing revolvers, shouting, beating down doors that did not open fast enough with their rifle butts, ransacking the church and the bell tower in search of English and French soldiers who they claimed were being hidden by the inhabitants.’

Joseph Cabaret, the distinguished old schoolteacher, was dragged into the street by his white goatee and told to identify which perfidious Frenchman had killed the hussar, whose dead horse still lay in the street, abuzz with flies. ‘Hand over the guilty man or it is death for you and the village goes up in flames.’ The curé Ledieu was struck in the face by an Uhlan, a German cavalryman. Delabranche, the elderly pharmacist, was taken away, tied to a tree, beaten up, and then locked in the town cells with his hands ‘so tightly bound, they bled’. Henri Godé, the mild and diminutive deputy mayor of Le Câtelet, was also ‘arrested’ and hog-tied, along with the town notary, Léon Lege.

A bullet retrieved from the body of the cavalry officer thought to have been killed by Guy Lourdel, was found to be of English manufacture, but the German officer in command continued to insist that even if a Frenchman had not fired the fatal shot this was a measure of incompetence rather than innocence. ‘Bring us the sniper or else at 7.00 a.m. you will be shot and this place will be burned to the ground,’ he warned.

Lourdel was a wildly eccentric man with a patriotism verging on mania and a commitment to his government and country that was excessive even for a tax inspector. At the age of thirteen, he had joined a band of partisans in the Franco-Prussian War, and on the first day of mobilisation in 1914 he had dispatched his three sons to war. He attempted to join up himself but, at fifty-seven, he had been rejected as too old.

At dawn, Lourdel presented himself to the German officers now lodged in Mademoiselle d’Alincourt’s château, proudly acknowledging that he had opened fire on the German troops, but also pretending to be even more mad than he was. ‘He knew he had to take whatever was coming to him, for the sake of the village which was in such deadly peril on account of his bravura, but also for the sake of his self-respect,’ a neighbour later wrote. ‘He put on a good performance as a bloodthirsty killer, and standing amid the Germans, as if blind to their presence, he kept shouting: “Kill the lot of them!”.’ Lourdel’s captors became convinced they were in the presence of a genuine lunatic, and locked him up instead of killing him.

Terrified, several villagers had hidden in the undergrowth of the moat surrounding the medieval castle. That night a jumpy German sentry heard a rustling in the bushes around the moat and opened fire, shooting one Madame Lemaire-Liénard through the throat. She had taken refuge there with her husband and daughter. ‘With the death of the woman the German officers began to calm down. They had wanted innocent blood, and they got it.’

After twenty-four hours, the invaders finally released their hostages and the main body of troops moved on. A handful of guards remained behind to keep order and in the wake of their first, traumatic experience of German occupation the people of Le Câtelet ‘cleaned out and disinfected their homes’. The body of the horse, ‘which had been covered in religious ornaments by the passing German troops, was dragged away’. So too was the tax inspector Lourdel; he was taken under guard, still raving for German blood, to Reims. The city, and Lourdel, were duly liberated a few weeks later in the Allied counterattack, and Le Câtelet’s eccentric patriot finally succeeded in persuading the French army to allow him to join the ranks. He survived the battles of Verdun and the Somme, was wounded twice, and lived on to a great age boasting of how he had resisted the German army single-handed.

Although Lourdel’s actions had ultimately released him from life in German-occupied France, the more cautious folk of the region drew quite another moral from the tale: Lourdel is still referred to as ‘that imbecile who shot at the German hussar and nearly had the lot of us killed’. There were other ways to defy the Germans than by shooting at them, they said. The German occupation was only a few hours old, but already some had concluded that accommodation rather than confrontation was the best approach.

The most immediate manifestation of that moral dilemma, which would trouble the occupied people of northern France for the next four years, was how to react to the scores of British soldiers left behind in the retreat. At Vendhuile, just hours before the Germans arrived, the mayor spotted a group of British soldiers drinking in a bar and could not suppress the suspicion that ‘they wanted to be caught’. In Hargicourt the deputy mayor reported an English soldier who had hidden in woods by the road into the village who ‘had the audacity to open fire, as a despairing gesture’, when the enemy columns arrived, and then ran to hide in the nearest barn. When German troops began bayoneting the straw, he emerged and surrendered.