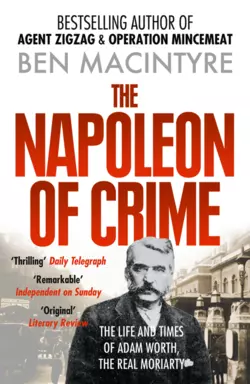

The Napoleon of Crime: The Life and Times of Adam Worth, the Real Moriarty

Ben Macintyre

The rumbustious true story of the Victorian master thief who was the model for Conan Doyle’s Moriarty, Sherlock Holmes’ arch-rival. From the bestselling author of ‘Operation Mincemeat’ and ‘Agent Zigzag’.Adam Worth was the greatest master criminal of Victorian times. Abjuring violence, setting himself up as a perfectly respectable gentleman, he became the ringleader for the largest criminal network in the world and the model for Conan Doyle’s evil genius, Moriarty.At the height of his powers, he stole Gainsborough’s famous portrait of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, then the world’s most valuable painting, from its London showroom. The duchess became his constant companion, the symbol and substance of his achievements. At the end of his career, he returned the painting, having gained nothing material from its theft.Worth’s Sherlock Holmes was William Pinkerton, founder of America’s first and greatest detective agency. Their parallel lives form the basis for this extraordinary book, which opens a window on the seedy Victorian underworld, wittily exposing society’s hypocrisy and double standards in a storytelling tour de force.Note that it has not been possible to include the same picture content that appeared in the original print version.

The Napoleon of Crime

The Life and Times of Adam Worth, the Real Moriarty

Ben Macintyre

Copyright (#ulink_925507b0-4999-5eea-b8cc-2ebc2105ce82)

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

Copyright © Ben Macintyre 1997

Ben Macintyre asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780006550624

Ebook Edition © JANUARY 2012 ISBN: 9780007383641

Version: 2017-02-20

(#u1eacf778-7c04-5a35-ab6c-3cd8c982feb3)FOR KATE

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#u6dbd4b93-6772-55dc-b775-fa214fcba14b)

Title Page (#u071f6d82-8054-54b1-a715-c041805a32d8)

Copyright (#u9f5fe0e1-7b83-5e68-9795-82a8f7c1db20)

Dedication (#u58a54c7f-230c-5fec-affc-b5756b3187df)

Preface (#u63dcef5a-66de-5a9f-ae3d-b586f89f5620)

The Elopement (#u67ffa931-bd0a-502b-b9ce-72d8d02f7309)

A Fine War (#u53303515-22bb-529f-8f27-846a9eaa6ff7)

The Manhattan Mob (#u3b0620b5-c9d2-5065-9a88-f3715fb45cfa)

The Professionals (#u33a06b19-3ec2-52d8-8288-e7bae7b7c282)

The Robbers’ Bride (#u7360fd56-2b01-58d1-b2d7-80eb81ea6c8d)

An American Bar in Paris (#ubfb08928-01bd-5c96-9de9-418877f01268)

The Duchess (#uc63445cc-e1b8-51ce-9198-8e9238e12a9c)

Dr Jekyll and Mr Worth (#u37add81e-390a-5a6e-8055-27979a01181c)

Cold Turkey (#litres_trial_promo)

A Great Lady Holds a Reception (#litres_trial_promo)

A Courtship and a Kidnapping (#litres_trial_promo)

A Wanted Woman (#litres_trial_promo)

My Fair Lady (#litres_trial_promo)

Kitty Flynn, Society Queen (#litres_trial_promo)

Dishonour Among Thieves (#litres_trial_promo)

Rough Diamonds (#litres_trial_promo)

A Silk Glove Man (#litres_trial_promo)

Bootless Footpads (#litres_trial_promo)

Worth’s Waterloo (#litres_trial_promo)

The Trial (#litres_trial_promo)

Gentleman in Chains (#litres_trial_promo)

Le Brigand International (#litres_trial_promo)

Alias Moriarty (#litres_trial_promo)

Atonement (#litres_trial_promo)

Moriarty Confesses to Holmes (#litres_trial_promo)

The Bellboy’s Burden (#litres_trial_promo)

Pierpont Morgan, the Napoleon of Wall Street (#litres_trial_promo)

Return of the Prodigal Duchess (#litres_trial_promo)

Nemo’s Grave (#litres_trial_promo)

EPILOGUE: The Inheritors (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Preface (#ulink_ce6cf8e7-ddc8-56ec-8a03-f35a2c2d56c9)

I had come to Los Angeles to cover the latest instalment in the Rodney King case, that grimly defining saga of modern times. But I left the city with a very different tale of cops and robbers.

The white Los Angeles policemen who had been filmed by an amateur cameraman beating up a black motorist were in the dock for a second time, stolidly proclaiming their innocence. It was confidently predicted that the city was on the verge of another riot. One afternoon, when the jury had retired to consider its verdict, I decided to drive out to the suburb of Van Nuys to explore the archives of the Pinkerton’s Detective Agency, thinking I might write an article for The Times about American law enforcement in another, sepia-tinted age, a world away from the thugs on trial downtown, or those in the ghetto who might take to the streets if they escaped justice again.

The Pinkertons. The name itself summoned up hard lawmen with comic facial hair and six-shooters, riding out after the likes of Jesse James, the Reno gang, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Shown into the basement archive by a bored secretary popping bubble gum, I immediately realized there was far more here than could possibly be digested in a year, let alone an afternoon. The rows of cabinets literally overflowed with files, a testament to the painstaking methods of America’s earliest detectives. After an hour or so of random delving, I picked up a bound scrapbook, dated 1902. Leafing through it, I came across this fragment of newsprint:

SUNDAY OREGONIAN, PORTLAND, JULY 27, 1902.

ADAM WORTH, GREATEST THIEF OF MODERN TIMES; STOLE $3,000,000

THIS is the story of Adam Worth.

If a fiction writer could conceive such a story, he might well hesitate to write it for fear of being accused of using the wildly improbable.

The sober, cold, technical judgment passed upon Adam Worth by the greatest thief-hunters of America and Great Britain is that he was the most remarkable, most successful and most dangerous professional criminal ever known to modern times.

Adam Worth, in a life of crime covering almost half a century, looted at least $2,000,000, and most probably as much as $3,000,000.

He cruised through the Mediterranean on a steam yacht with a crew of 20 men, and left a trail of looted cities behind him.

He was caught only once, and then through a blunder by a stupid confederate.

He ruled the shrewdest criminals, and planned deeds for them with craft that bade defiance to the best detective talent in the world.

The police of America and Europe were eager to take him for years, and for years he perpetrated every form of theft – check-forging, swindling, larceny, safe-cracking, diamond robbery, mail robbery, burglary of every degree, ‘hold-ups’ on the road and bank robbery – under their very noses with complete immunity.

There were three redeeming features in the life of this lost human creature.

He worshiped his family and regarded and treated his loved ones as something sacred. His wife never knew that he was a criminal. His children are living in the United States today in complete ignorance of the fact that their father was the master-thief of the civilized world.

He never was guilty of violence, and would have nothing to do under any circumstances with any one who did.

He never forsook a friend or accomplice.

Because of that loyalty he once rescued his band of forgers from a Turkish prison and then from Greek brigands, reducing himself to beggary to do it.

Because of that loyalty he became ‘The Man Who Stole the Gainsborough.’

The reason for that theft will be told here for the first time. Until now, all who knew it were under binding obligations of silence. The motive that caused the deed was unique in the history of modern crime.

And Adam Worth, who had millions, who once flipped coins for £100 a toss, who at one time had an interest in a racing stable, had a steam yacht and a fast sailing yacht, died a few weeks ago as he had begun – a poor, penniless thief.

He towered above all other criminals of his time; he was so far in advance of them that the man who hunted him weakened before his masterful intellect; but the inexorable fate that pursues the breaker of moral law caught him and finished him at last where the man-made law was powerless.

When Adam Worth died he was as much a mystery – aside from certain officials and detective inspectors of Scotland Yard, the Pinkertons, and a very few American police officials – even to the great majority of the police officials of the world as he had been throughout his life. If he had not become prominent recently as the man who stole and returned the Gainsborough portrait, the public probably never would have heard of him at all. Only a very few of the most able detectives of the world knew him even by sight. Still less knew anything about him. The story that follows is an absolute and minutely exact history, verified in every particular and vouched for by the men who spent almost half a century in trying to hunt him down.

Nothing in this history is left to conjecture.

The rest of the promised article, infuriatingly, had not been pasted into the book. Time and again I read this clipping, extravagant in its claims even by the journalistic standards of the day, and a small LA riot of excitement began building somewhere in the back of my mind. Then my electronic pager sounded, bringing me hurtling back to the present with the news that a verdict in the Rodney King trial was imminent. By the next afternoon, two of the cops had been found guilty, the inhabitants of South Central Los Angeles had obligingly decided not to go on the rampage, and I was back in Van Nuys, combing the Pinkerton archive for every scrap of material I could find on Adam Worth. The detectives, I soon learned, had hunted Worth across the world for decades with dogged perseverance, and the result was a wealth of documentation: six complete chronological folders, tied together with string and bulging with photographs, letters, more newspaper articles and hundreds of memos by the Pinkerton detectives, each one written in meticulous copper-plate and relating a tale even more intriguing and peculiar than the nameless Sunday Oregonian writer had implied.

For Adam Worth, it transpired, was far more than simply a talented crook. A professional charlatan, he was that most feared of Victorian bogeymen: the double-man, the charming rascal, the respectable and civilized Dr Jekyll by day whose villainy emerged only under cover of night. Worth made a myth of his own life, building a thick smokescreen of wealth and possessions to cover a multitude of crimes that had started with picking pockets and desertion and later expanded to include safe-cracking on an industrial scale, international forgery, jewel theft and highway robbery. The Worth dossiers revealed a vivid rogues’ gallery of crooks, aristocrats, con men, molls, mobsters and policemen, all revolving around this singular man. In minute detail, the detectives described his criminal network, radiating out of Paris and London and stretching from Jamaica to South Africa, from America to Turkey.

I left the Pinkerton archive elated but tantalized. The material was vast but incomplete. Like any sensible crook anxious to avoid detection, Worth had not written his memoirs and had left behind only a handful of coded letters. My initial researches had raised more questions than they answered. How had Worth evolved his contradictory moral code? How had he escaped capture for so many years? How had he transformed himself from a penniless German-Jewish emigrant from Cambridge, Massachusetts, into an English milord in the aristocratic heart of London?

One mystery intrigued me more than all the others. In the early summer of 1876, at the height of his criminal powers, Worth stole from a London art gallery in the dead of night The Duchess of Devonshire, Thomas Gainsborough’s famous portrait and then the most expensive painting ever sold. What had possessed him? And why, still more bizarrely, had he kept the great painting, in secret, for the next twenty-five years? The Gainsborough portrait, I was already certain, held the key to unlocking the secret of Adam Worth.

California proved to be only the first stop on a long trail. Slowly I assembled a fuller picture, from letters, diaries, published memoirs by other criminals, newspaper accounts and the archives of Scotland Yard, the Paris Sûreté, Agnew’s art gallery and Chatsworth House. Other, quite unexpected discoveries, soon followed.

Worth invented his own life as a dramatic romance. But when the Sunday Oregonian talked of his piquant history as the very stuff of fiction, the newspaper was telling the literal truth. The English detective Sherlock Holmes was already a household name when Sir Arthur Conan Doyle first learned of Worth’s villainous deeds. The great English writer, it turns out, had used Worth as the model for none other than Professor Moriarty, Holmes’s evil, art-collecting adversary and one of the most memorable criminals in literature. Conan Doyle was not alone in his debt to Worth, for writers as diverse as Henry James and Rosamund De Zeer Marshall, an author of wartime bodice-rippers, also found inspiration in Worth’s activities.

My quarry led me on some unlikely pilgrimages: to the grand building in Piccadilly near Fortnum & Mason’s that was Worth’s criminal headquarters; to the Civil War battlefield where he first reinvented himself; to the London art gallery where he stole his most prized possession and to a room in Sotheby’s auction house where, for the first time, I encountered that indelible image face to face. As I write, from the Paris office of The Times, I can look across the Place de l’Opéra to the Grand Hotel, where Worth ran an illegal casino and held court with his mistress in the 1870s. I am still not sure whether I have been following Worth for the last four years, or whether he has been shadowing me.

I had set off to hunt down ‘The Greatest Thief of Modern Times’. What I found turned out to be an unlikely reflection of those times, and our own: a Victorian gentleman and master thief who merged the highest moral principles with the lowest criminal cunning. What follows is a story that has never been told before; it is a story of dual personalities, double standards and heroic hypocrisy.

This is the story of Adam Worth.

Paris

March, 1997

‘Adam Worth was the Napoleon (#litres_trial_promo) of the criminal world. None other could hold a candle to him.’

SIR ROBERT ANDERSON, Head of Criminal Investigation, Scotland Yard, 1907

‘He is the Napoleon of crime, Watson. He is the organizer of half that is evil and of nearly all that is undetected in this great city. He is a genius, a philosopher, an abstract thinker. He has a brain of the first order. He sits motionless, like a spider at the centre of its web, but that web has a thousand radiations, and he knows well every quiver of each of them. He does little himself. He only plans. But his agents are numerous and splendidly organized … the central power which uses the agent is never caught—never so much as suspected.’

SHERLOCK HOLMES on Professor Moriarty in ‘The Final Problem’ by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

‘I hope you have not been (#litres_trial_promo) leading a double life, pretending to be wicked and being really good all the time. That would be hypocrisy.’

OSCAR WILDE, The Importance of Being Earnest

£1000

R E W A R D.

STOLEN

Between half-past nine p.m. 25th, and 7 a.m. 26th inst, from the Picture Gallery, No. 39b, Old Bond Street, the celebrated Oil Painting, by Gainsborough, of the Duchess of Devonshire, Size 60 inches by 45 inches, without frame or stretcher.

The above Reward will be paid by Messrs. Agnew and Sons, No. 39b, Old Bond Street, to any person giving such information as will lead to the apprehension and conviction of the thief or thieves, and recovery of the painting.

Information to Superintendent Williamson, Detective Department, Great Scotland Yard, London, S.W.

ONE (#ulink_462fe240-f68d-5740-b613-2e1d70cf1511)

The Elopement (#ulink_462fe240-f68d-5740-b613-2e1d70cf1511)

ON A MISTY MAY MIDNIGHT in the year 1876, three men emerged from a fashionable address in Piccadilly with top hats on their heads, money in their pockets and burglary, on a grand scale, on their minds. At a deliberate pace the trio headed along the empty thoroughfare and at the point where Piccadilly intersects with Old Bond Street, they came to a stop. Famed for its art galleries and antiques shops, Old Bond Street by day was choked with the carriages of the wealthy, the well-bred and the culturally well-informed. Now it was quite deserted.

The three men exchanged a few words at the corner of the street before one slipped into a doorway, invisible beyond the dancing gaslight shadows, while the other two turned right into Old Bond Street. They made an incongruous pair as they walked on: one was slight and dapper, of some thirty-five years in age, with long, clipped moustaches and dressed in the height of modern elegance, complete with pearl buttons and gold watch-chain. The other, ambling a few paces behind, was a towering fellow with grizzled mutton-chop whiskers, whose ill-fitting frock coat barely contained a barrel chest. Had anyone been there to observe the couple, they might have assumed them to be a rich man taking the night air with his unprepossessing valet after a substantial dinner at his club.

Outside the art gallery of Thomas Agnew & Sons, at 39 Old Bond Street, the two men paused and while the aristocrat extinguished his cheroot and admired his own faint but stylish reflection in the glass, his brutish companion glanced furtively up and down the street. Then, at a word from his master, the giant flattened himself against the wall and joined his hands in a stirrup, into which the smaller man placed a well-shod foot, for all the world as if he were climbing onto a thoroughbred. With a grunt the big man heaved the little fellow up the wall and in a moment he had scrambled nimbly onto the window ledge some fifteen feet above the pavement. Balancing precariously, he whipped out a small crowbar, wrenched open the casement window and slipped inside, as his companion vanished from sight beneath the gallery portal.

The room was unfurnished and unlit, but by the faint glow from the pavement gaslight a large painting in a gilt frame could be discerned on the opposite wall. The little man removed his hat as he drew closer.

The woman in the portrait, already famed throughout London as the most exquisite beauty ever to grace a canvas, gazed down with an imperious and inquisitive eye. Curls cascaded from beneath a broad-brimmed hat, set at a rakish angle to frame a painted glance at once beckoning and mocking, and a smile just one quiver short of a full pout.

The faint rumble of a night-watchman’s snores wafted up from the room below, as the little gentleman unclipped a thick velvet rope that held the inquisitive public back from the painting during daylight hours. Extracting a sharp blade from his pocket, with infinite care he cut the portrait from its frame and laid it on the gallery floor. From his coat he took a small pot of paste and, using the tasselled end of the velvet rope, he daubed the back of the canvas to make it supple and then rolled it up with the paint facing outwards to avoid cracking the surface, before slipping it inside his frock coat.

A few seconds later he had scrambled back down his monstrous assistant to the street below. A low whistle summoned the lookout from his street corner, and with jaunty step the little dandy set off back down Piccadilly, the stolen portrait pressed to his breast and his two rascally companions trailing behind.

The painted lady was Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, once celebrated as the fairest and wickedest woman in Georgian England. The painter was the great Thomas Gainsborough, who had executed this, one of his greatest portraits, around 1787. A few weeks before the events just recounted, the painting had been sold at auction for ten thousand guineas, at that time the highest price ever paid for a work of art, causing a sensation. Georgiana of Devonshire, nee Spencer, was once again the talk of London, much as her great-great-great grandniece Diana, Princess of Wales, nee Spencer, would become in our age.

During Georgiana’s lifetime, which ended in 1806, her admirers vied to pay tribute to ‘the amenity and graces (#litres_trial_promo) of her deportment, her irresistible manners, and the seduction of her society’. Her detractors, however, considered her a shameless harpy, a gambler, a drunk and a threat to civilized morals who openly lived in a ménage à trois with her husband and his mistress. No woman of the time aroused more envy, or provoked more gossip.

The sale of Gainsborough’s great painting to the art dealer William Agnew had been the occasion for a fresh burst of Georgiana-mania. Gainsborough’s vision of enigmatic loveliness, and the extraordinary value now attached to it, became the talk of London. Victorian commentators, like their eighteenth-century predecessors, heaped praise once more on this icon of female beauty, while rehearsing some of the fruitier aspects of her sexual history.

When the painting was stolen, the public interest in Gainsborough’s Duchess reached fever-pitch. The painting acquired huge cultural and sexual symbolism. It was praised, reproduced and parodied time and again, the Marilyn Monroe poster of its day, while Georgiana herself was again held up as the ultimate symbol of feminine coquetry. The name of the man who kidnapped the Duchess that night in 1876 was Adam Worth, alias Henry J. Raymond, wealthy resident of Mayfair, sporting gentleman about town and criminal mastermind. At the time of the theft Worth was at the peak of his powers, controlling a small army of lesser felons in an astonishing criminal industry. Stealing the picture was an act of larceny, but also one of hubris and romance. Georgiana and her portrait represented the very pinnacle of English high society. Worth, by contrast, was a German-born Jew raised in abject poverty in America who, through an unbroken record of crime, had assembled the trappings of English privilege and status, and every appearance of virtue. The grand duchess had died seventy years before Worth decided, in his own words, to ‘elope’ with her portrait, beginning a strange, true Victorian love-affair between a crook and a canvas.

TWO (#ulink_e40c0a45-52c0-5195-85c6-331ab37c0829)

A Fine War (#ulink_e40c0a45-52c0-5195-85c6-331ab37c0829)

FOURTEEN YEARS EARLIER, at the end of August 1862, the armies of the Union and the Confederacy had come to grips in a muddy Virginia field and blasted away at each other for two days in an encounter known to history as the Second Battle of Bull Run, one of the very bloodiest engagements of the American Civil War.

According to official war records, more than three thousand soldiers died in that carnage including one Adam Worth, who was just eighteen at the time.

Bull Run was the scene of Worth’s first death and first reincarnation. Reports of his death were, of course, greatly exaggerated and so far from perishing on the Virginia battlefields, the young Worth had survived the war in excellent health with a changed name, a deep aversion to bloodshed and a wholly new career as an impostor stretching out before him. The Civil War almost destroyed America, but after the bloodletting the country fashioned itself anew, and so did Worth. Over the next forty years he would vanish and then reappear under a new name with a regularity and ease that baffled the police of three continents.

Worth was notoriously reticent when it came to discussing the years before his strange renaissance at Bull Run – the better, perhaps, to preserve the myriad myths that clustered around them. Some later accounts insisted that he was the product of a wealthy Yankee family and an expensive education, a gentleman criminal in the Raffles tradition. Another stated, categorically and without corroboration, that ‘his father was a Russian (#litres_trial_promo) Pole and his mother a German’. The great detective William Pinkerton, a man who came to know Worth better than any other, insisted that he was the child of a rich Massachusetts burgher who had sent his son to a private academy to learn an honest business, only to see him seduced into crime by bad company in the stews of New York. ‘Had he continued (#litres_trial_promo) an upright life, he undoubtedly would have become famous as a businessman,’ the worthy Pinkerton lamented. Another important figure in Worth’s life, a notorious thief and gangster’s moll named Sophie Lyons, concurred in the belief that Worth had come from good stock, reporting that he was ‘born of an excellent (#litres_trial_promo) family and well educated, [but] formed bad habits and developed a passion for gambling’.

Worth himself was the last person to deny such glamorous beginnings which were, like so many aspects of his existence, a very considerable distance from the truth. Adam Worth (or Wirth, or even, occasionally, Werth) was born in 1844 somewhere in eastern Germany. His father and mother were German Jews who emigrated to the United States when Worth was just five years old. Speaking no English and almost destitute, Worth père set up shop as a tailor in the town of Cambridge, Massachusetts. No other details about Worth’s mother and father have survived, but one may surmise that their parenting skills, particularly in the area of ethical guidance, were distinctly lacking: not only did Adam Worth take to crime at an early age, but his younger brother John quickly followed suit and his sister, Harriet, continued the family tradition by marrying a crooked lawyer.

Worth’s first lesson in swindling was apparently learned in a Cambridge school playground. Pinkerton liked to tell the story of how Worth ‘entered school when six years (#litres_trial_promo) of age, and was very soon after, as he himself stated, drawn into a trade with a boy larger than himself, who offered to give him a brand new penny for two old ones’. The child Worth, finding the newly minted coin a more attractive object than his two old ones, agreed to the swap and returned home to show his father, who ‘gave him a most (#litres_trial_promo) unmerciful whipping’, thus ‘impressing on him (#litres_trial_promo) the value of the new penny as against his two old ones’.

‘From that day (#litres_trial_promo) until his death, no one, be he friend or foe, honest or dishonest, Negro or Indian, relative or stranger, ever got the better of Adam Worth in any business transactions, regular or irregular,’ Pinkerton concluded.

The young Worth grew up, or rather did not grow up, to be small in stature, measuring between five feet four and five feet five, according to police records. Contemporaries made much of his lack of height, and his criminal colleagues, who were nothing if not literal when it came to the allocation of sobriquets, called him ‘Little Adam’. In reality, for an age when human beings were appreciably smaller than they are now, he was not much below average height, but it suited the purposes of those who could not help admiring him to make our man out to be a midget, for thus his evil-doing was magnified and his ability to thwart authority appeared the more remarkable. When the Scotland Yard detective Robert Anderson called him ‘the Napoleon of (#litres_trial_promo) the criminal world’, he was referring not only to the man’s nefarious accomplishments and criminal stature, but also to his contrasting lack of inches. The undersized Worth quickly developed an outsized Napoleonic complex.

Worth’s height was always the first physical feature noted by the various detectives, policemen, crooks and lovers who came into contact with him. The second was his eyes, which were dark, almost black, penetrating voids beneath shaggy eyebrows, suggestive of intelligence and determination. When he became enraged, which was seldom, they bulged unpleasantly. He had thick hair, which he wore short and combed to one side, a prominent curved nose and, in later life, a long moustache which curled across his cheeks to meet a pair of mighty side whiskers.

If Worth’s tough childhood left him with a cynical determination to outdo his peers by guile, it also seems to have imbued him with an intense romanticism. As his father scraped together a living to keep his brood alive in the malodorous hovel that was the Worth family home, his eldest son’s imagination released him to a world of grand dinners, fine apparel and civilized conversation.

In the Harvard students who paraded through Cambridge, the immigrant Jewish urchin had ample opportunity to observe the outward show of wealth and privilege. The brighter the penny, he saw, the easier the counterfeit. Ashamed of his lowly origins, frustrated by impecunity, the young Worth clearly felt himself to be the equal of the finest of the young gentlemen strutting Boston Common. Their wealth and sophistication provoked ambivalent feelings, of envy, resentment and anger, but also of admiration and desire. Worth resolved to ‘better’ himself.

America, then as now, promised all things to all men, even if it did not always deliver. It was a time when ‘ambition (#litres_trial_promo)’, as Cardinal Newman wrote, ‘sets everyone on the lookout to succeed and to rise in life, to amass money, to gain power, to depress his rivals, to triumph over his hitherto superiors, to affect a consequence and a gentility which he had not before’. Worth shared those aspirations, and would eventually realize them. His methods alone would set him apart from other ‘self-made men’, for what others had earned, inherited or bought, he would simply steal, winning respectability by robbery, effrontery and fraud. Where his father had toiled to make clothes for the vanity of rich men, Worth would spin himself the dazzling outfit of a pretender, from pilfered cloth.

But it would be wrong to see the young Worth as merely a creature of immorality, a natural-born wrecker of the social fabric. From an early age he espoused many of the worthiest principles: loyalty to family and friends, the virtues of hard work, perseverance, generosity, charity and courage. As he entered his teens Little Adam was already evolving into a character of many and conflicting parts: selfish, greedy and generous to a fault, at once ruthless and romantic. He regarded his fellow men, and particularly his social superiors, with undiluted cynicism, yet he would never swindle a friend, rob a poor man or harm the harmless. He was acutely aware of the difference between right and wrong and evolved a code of behaviour that he held with the same resolute conviction as would any pillar of society, while he turned society’s codes upside down. Adam Worth had plenty of time for morals; it was laws he disdained. The hard, uncertain circumstances of Worth’s early life left him with the deeply held conviction that it was possible to be a ‘good’ man, at least in his own estimation, while pursuing a life of calculated deceit.

As he emerged from a deprived childhood into an adolescence that offered little better, Worth took the fateful decision to rid himself of his first, unglamorous life. At the age of fourteen, Worth ran away from home, leaving behind his humble parents and their status as social outcasts. The idea of a career in crime and imposture may not yet have formed in his young mind, but Worth already knew what he did not want. He never again set foot inside his childhood home, but a need for family love, and perhaps also for the strong father-figure that his own father never was, marked the rest of his restless existence.

After some months of leading ‘a vagabond life (#litres_trial_promo) in the city of Boston’, he drifted to New York where he took, for the first and only time, an honest job as a clerk ‘in one of the (#litres_trial_promo) leading stores in New York City’. Worth never offered any details of this brief flirtation with paid work, master criminals being notoriously touchy about that sort of thing, and the experiment was, anyway, cut short by the start of the American Civil War. At the age of seventeen, the store clerk from Massachusetts promptly abandoned the tedious job of filling in ledgers, and joined a New York regiment in the Union Army preparing to march south for battle.

Worth’s name first appears in the register of the 34th New York Light Artillery, better known as the Flushing or ‘L’ Battery, which assembled in Long Island. He was officially mustered into the regiment in New York City on 28 November 1861, and received a ‘bounty of $1,000 (#litres_trial_promo)’, according to Pinkerton. Many young recruits inflated their ages upon joining up, to appear more mature than they were and thus hasten possible promotion. The seventeen-year-old Worth gave his age as twenty, his first recorded lie.

The commander of the Flushing Battery was a German-born shoemaker named Jacob Roemer, who had emigrated to New York in 1839. Captain Roemer was a fussy, irascible man with a thrusting beard, crossed eyes and the bristling face of a natural martinet. Vain, blustering and courageous to the point of insanity, many years later Roemer wrote a massively self-inflating memoir, apparently designed to prove that the author himself was primarily responsible for winning the war. Young Worth, Roemer’s fellow countryman by birth, seems to have caught the eye of his commander, for he was soon promoted to corporal and then, on 30 June 1862, to the rank of sergeant in command of his own cannon and five men. Worth was well on his way to becoming a successful soldier, but he had by now fallen into bad, and thoroughly congenial, company. ‘He became associated (#litres_trial_promo) with some wild companions, whom he had met at dances and frolics’ while in New York, Pinkerton later recorded.

The life of the Flushing Battery was anything but frolicsome. For several months, the soldiers drilled on Long Island, learning to wheel the field guns under the obsessively critical inspection of Captain Roemer. Then, in early summer, Captain Jacob Roemer, five commissioned officers, Sergeant Adam Worth, 150 men, no horses, 12 baggage mules and a laundry woman packed up and headed south to join the rest of the Union Army under the command of that dithering incompetent, General Pope, deservedly one of the least remembered generals of the entire Civil War. In Washington they drilled some more, around the unfinished Capitol building. Worth clearly hated every moment, and even Roemer admitted that Camp Barry was a ‘mud hole (#litres_trial_promo)’.

‘All we wanted (#litres_trial_promo) was a chance to prove our devotion and our loyalty to our country,’ the prickly and patriotic Roemer wrote. Worth already had other ideas. Indeed, his first taste of army life compounded a blossoming disrespect for authority.

During the early part of August the Union Army and the Confederates, under the command of Thomas ‘Stonewall’ Jackson, warily circled each other in the fields and hills of Virginia. The Flushing Battery took part in several violent skirmishes, but it was not until late August that Roemer’s men tasted the full horror of battle when the two sides met head on, for the second time in the war, near the stream known as Bull Run.

On the evening of 28 August, thanks largely to Captain Roemer’s absurd determination to cover himself and his men in glory and blood, the Flushing Battery found itself engaged at close quarters with the enemy in the middle of Manassas valley. Roemer enjoyed every moment. ‘Shot and shell flew (#litres_trial_promo) thick and fast,’ he recalled, as the gunners fired off 207 rounds and somehow beat the enemy back. ‘I was triumphant,’ wrote Roemer. One of his terrified lieutenants, however, was found hiding under a bush and had to be removed, gibbering, from the field. The battery commander was in his element, belting around the battlefield expecting, perhaps even hoping, to be shot by the enemy and leaving a trail of appropriately heroic last words as he went. On the 30th he gave a pep-talk to his troops. ‘Boys, it is no longer (#litres_trial_promo) of any use to keep from you what may be in store for us,’ he announced gleefully. ‘Before the sun sets to-night, many of you may have given up your lives; perhaps I myself will have to, but all I have to say is – Die like men; do not run like cowards. Stick to your guns, and, with the help of God and our own exertions, we may get through. Forward march.’ What Worth made of Roemer’s epic oratory may be deduced from his subsequent actions.

A few hours later L Battery was caught up in the fiercest engagement so far. ‘Bullets, shot and shell (#litres_trial_promo) fell like hail in a heavy storm … bullets were dropping all around and shells were ploughing up the ground. Men were tumbling, horses were falling and it certainly looked as though “de kingdom was a-comin”,’ recalled Roemer, who had his horse shot from under him and received, to his transparent delight, a flesh wound in the right thigh. Finally the enemy retreated. The Union Army was soundly defeated at Bull Run, but the unstable Captain Roemer regarded the battle as an immense personal victory.

From Adam Worth’s point of view, however, the most intriguing fact about the engagement at Bull Run is that he did not, officially speaking, survive it.

Roemer was unemotional in recording the passing of young Worth: ‘During this battle (#litres_trial_promo), generally known as the Second Battle of Bull Run or Manassas, 29-30 August 1862, the casualties in Battery L were fourteen enlisted men wounded (including Sergeant Adam Wirth [sic], mortally wounded) besides myself, three horses killed and 21 wounded.’ According to his army records, Adam Worth died at the Seminary Hospital, Georgetown, on 25 September from wounds received at the battle three weeks earlier.

What really happened to Adam Worth at Bull Run must be a matter of speculation for, unlike Roemer and for obvious reasons, he did not write his war memoirs. Certainly he was wounded during the engagement. He later boasted of the fact, yet the injury does not appear to have been serious. At some point between 30 August, when he was carried from the battlefield, and 25 September, when he was officially listed as dead, Worth successfully made his escape. Perhaps he swapped his identification with another, mortally wounded soldier, or perhaps in the confused aftermath of battle when so many injured and dying were crammed into the nation’s capital, he merely ended up as a fortuitous clerical error, marked down on the wrong list. Either way, Worth emerged from the battlefields of Virginia with only a superficial wound and an entirely new identity. Adam Worth was now officially no more, and thus could move on without fear of pursuit. For the first time, but not the last, he reinvented himself and became a professional ‘bounty jumper’.

Over the coming months Worth established a system: he would enlist in one regiment under an assumed name, collect whatever bounty was being offered, and then promptly desert. Thus he drifted from one part of the sprawling army to another, changing his alias at every stop and developing a talent for masquerade that would later become a full-time profession. William Pinkerton, who was himself a young soldier in the Union Army at the time, reported that Worth, after his first desertion and re-enlistment, was ‘stationed for a time (#litres_trial_promo) on Riker’s island, N.Y. [and] from there he was conveyed by steamship to the James River in Virginia, where he was assigned to one of the New York regiments in the Army of the Potomac.’ Although the war convinced Worth of the futility of violence, his desertions were prompted by avarice rather than cowardice, and he repeatedly found himself in the thick of battle including, according to Pinkerton, the famous Battle of the Wilderness in May 1864, an engagement scarcely less ferocious than the Battle of Bull Run.

Desertion was a lucrative but highly risky business. ‘On his third enlistment (#litres_trial_promo),’ according to one of his criminal associates, ‘he was recognised as a bounty jumper, and was in consequence sent, in company with others of his class, chained together, to the front of the Army of the Potomac.’ Once more, Worth somehow emerged unscathed; he promptly deserted and re-enlisted again. There was clearly a limit to how long Worth could get away with changing regiments so, in a remarkable act of brass cheek, he now decided to change sides. As a contemporary wrote: ‘About this time (#litres_trial_promo) General Lee of the Southern Army issued a proclamation to the effect that all Federal soldiers who would desert from the Federal armies to the Confederate lines, bringing their arms with them, would receive thirty dollars from the Confederate Government, and also receive a free pass to cross the frontier back into the United States by way of the adjoining States of West Virginia and Kentucky.’

The aspiring crook, untroubled by niceties such as loyalty to the Union cause, immediately ‘took advantage (#litres_trial_promo) of these exceptionally liberal terms, and deserted one night in company with some others, while doing picket duty’. He did not linger in the South, and having collected his thirty dollars travelled back ‘through the Confederate States (#litres_trial_promo) on foot, in order to gain the frontier of the Northern States’. He would doubtless have repeated the process several more times, but before he could do so the war came to an end, and so did the first phase of Worth’s criminal career.

Worth was just one of thousands of young soldiers to find themselves at loose ends with the declaration of peace. William Pinkerton, a man who came to play a defining role in Worth’s life and was to become his most reliable chronicler, was another. Before long the two men would become adversaries on either side of the law, then grudging mutual admirers, then co-conspirators and finally, most bizarrely, friends. Their paths did not cross until the war’s end, but already they were dark and light reflections of one another. Like the bright and tarnished pennies of Worth’s childhood, they were similar in value but utterly different in lustre.

The elder son of Allan Pinkerton, a Scotsman who had founded the great detective agency in Chicago in 1850, William Pinkerton was Worth’s exact contemporary and had enrolled in the Union Army at much the same time. Where Worth’s early life had been marked by material want and a complete absence of moral guidance, Pinkerton was brought up in well-to-do Chicago under a regime of the strictest ethical rules. Allan Pinkerton was a superb detective but a brutal father and a fantastic prig who hammered the virtues of honesty, integrity and raw courage into his children and employees with something close to fanaticism. William did his best to live up to these exacting standards, but could never be quite good enough. Working with his father, Abraham Lincoln’s official spymaster, William Pinkerton not only ran agents across the border into Confederate territory but was also present on the first flight of an observation hot-air balloon during the Civil War. Brave, bluff and energetic, Pinkerton was wounded in the knee by an exploding shell at the Battle of Antietam, having already ‘gained experience (#litres_trial_promo) that was invaluable to him in the vocation which he was to follow’. He attended Notre Dame College in Indiana for a year and then joined his father’s fast-growing detective agency where he soon established a reputation as a tireless lawman, one of the first and perhaps the greatest of the American detective breed. The Pinkertons chose as their symbol an unblinking human eye and the motto ‘The Eye that Never Sleeps’, from which the modern term ‘private eye’ has evolved.

The lives and subsequent careers of Worth and Pinkerton starkly demonstrate the moral duality that so obsessed Victorians. They shadowed and echoed one another, the detective playing Holmes to Worth’s Moriarty, yet they were birds of a feather in their tastes, attitudes and opinions. Both, to a remarkable degree, represented typical American stories of self-created men from immigrant stock, rugged in their opportunism, sturdy in their beliefs, but at opposite poles of conventional morality. Worth would have made an outstanding detective; Pinkerton, a talented criminal. The American Civil War was a grimly levelling experience, but its end allowed the country to begin to rebuild and reinvent itself once more. The two men emerged from the battlefields determined, like thousands of others, to make their mark. They took diametrically opposed routes to that goal, but a lifetime later the bounty jumper and the war hero would end up, in a way neither could have predicted, on the same side.

Pinkerton’s had been a remarkable war, but then the official military record of Sergeant Adam Worth was also one of unblemished bravery and tragic heroism: a young and promising soldier mortally wounded while defending the Union on the battlefield at Bull Run. In truth, of course, he had spent the war dodging the authorities, swapping sides, abandoning the flags of two rival armies and collecting a tidy profit along the way.

THREE (#ulink_94277fbc-6b1f-5c76-ae1b-419a1e277f1e)

The Manhattan Mob (#ulink_94277fbc-6b1f-5c76-ae1b-419a1e277f1e)

AFTER THE CIVIL WAR, Worth drifted, like so many other veterans, to New York City which, by the mid-1860s, had already become one of the most concentratedly criminal places on earth. The politicians were up for sale, the magistrates and police were corrupt, the poor often had little choice but to steal while the rich sometimes had little inclination not to, since they tended to get away with it. Seldom has history conspired to assemble, on one small island, such a vivid variety of pickpockets, con men, whores, swindlers, pimps, burglars, bank robbers, beggars, mobsmen and thieves of every description. Some of the worst professional criminals occupied positions of the greatest authority, for this was the era of Boss Tweed, probably the most magnificently venal politician New York has ever produced. Corruption and graft permeated the city like veins through marble, and those set in authority over the great, seething metropolis were often quite as dishonest as those they policed, and fleeced. As human detritus washed into lower Manhattan in the wake of the Civil War, the misery, and criminal opportunities, multiplied. In 1866 a Methodist bishop, Matthew Simpson, estimated that the city, with a total population of 800,000, included 30,000 thieves, 20,000 prostitutes, 3000 drinking houses and a further 2000 establishments dedicated to gambling. Huge wealth existed cheek by jowl with staggering poverty, and crime was endemic.

New York’s most famously bent lawyers, William Howe and Abraham Hummel, wrote a popular account of the wicked city, entitled In Danger, or Life in New York: A True History of the Great City’s Wiles and Temptations, which purported to be a warning against the perils of crime published in the interests of protecting the unwary. But it basically advertised the easy pickings on offer and provided a primer on the various methods of obtaining them, from blackmailing to card-sharping to safe-cracking. Howe and Hummel promised ‘elegant storehouses (#litres_trial_promo), crowded with the choicest and most costly goods, great banks whose vaults and safes contain more bullion than could be transported by the largest ship, colossal establishments teeming with diamonds, jewelry, and precious stones gathered from all the known and uncivilized portions of the globe – all this countless wealth, in some cases so insecurely guarded’. (The book was an instant best-seller and, according to one criminal expert, ‘became required reading (#litres_trial_promo) for every professional or would-be law-breaker’.)

It was only natural that an ambitious and aspiring felon should make his way to New York and, once there, learn quickly. Determined to avoid returning to work as a mere clerk and hardened by his wartime experiences, Adam Worth took his place in the thieving throng. ‘On account of his (#litres_trial_promo) acquaintance with bounty jumpers, he finally became associated with professional thieves and crooked people generally, and from that time on his career was one of wrong doing.’ Pinkerton glumly recounted.

Worth soon found himself in the Bowery district of Manhattan, an area of legendary seediness and home to a large and thriving criminal community which was divided, for the most part, into gangs: the Plug Uglies, the Roach Guards, the Forty Thieves, the Dead Rabbits, the Bowery Boys, the Slaughter Housers, the Buckaroos, the Whyos and more. Many of these gangsters were merely exceptionally violent thugs, whose criminal specialities extended no further than straightforward mugging, murder and mayhem, often inflicted on each other and usually carried out under the influence of prodigious quantities of alcohol laced with turpentine, camphor and any other intoxicant, however lethal, that happened to be on hand.

‘Most of the saloons (#litres_trial_promo) never closed. Or if they did, for just long enough to be cleaned out and then to begin afresh drinking, fighting, cursing, gambling, and the Lord only knows what,’ recalled Eddie Guerin, a useless crook but successful memoirist who would eventually become Worth’s friend and colleague. The three thousand saloons noted by Bishop Simpson included such euphonious establishments as the Ruins, Milligan’s Hell, Chain and Locker, Hell Gate, the Morgue, McGurk’s Suicide Hall, Inferno, Hell Hole, Tub of Blood, Cripples’ Home and the Dump. But if the nomenclature of the dives was indicative of the immorality therein, the names of the clientele were still more telling: Boiled Oysters Malloy; Ludwig the Bloodsucker, a vampire who had hair ‘growing from every orifice (#litres_trial_promo)’; Wreck Donovan; Piggy Noles; the pirate Scotchy Lavelle, who later employed Irving Berlin as a singing waiter in his bar; Eat-em-up Jack McManus; Eddie the Plague; Hungry Joe Lewis, who once diddled Oscar Wilde out of five thousand dollars at banco; Gyp the Blood; the psychotic Hop-Along Peter, who tended, for no reason anyone could explain, to attack policemen on sight; Dago Frank; Hell-Cat Maggie, who filed her teeth to points and had sharp brass fingernails; Pugsy Hurley and Gallus Mag, a terrifying dame who ran the Hole-in-the-Wall saloon and periodically bit the ears off obstreperous customers and kept them in a pickling jar above the bar ‘pour encourager les autres’; Big Jack Zelig, who would, according to his own bill of fare, cut up a face for one dollar and kill a man for ten; Hoggy Walsh, Slops Connally and Baboon Dooley of the Whyos gang; One-Lung Curran, who stole coats from policemen; Goo Goo Knox; Happy Jack Mulraney, who killed a saloon keeper for laughing at the facial twitch which led to his sobriquet; brothel-keepers Hester Jane ‘the Grabber’ Haskins and Red Light Lizzie; and the unforgettable Sadie ‘the Goat’, a river pirate and leader of the Charlton Street Gang which occupied an empty gin mill on the East Side waterfront and terrorized farms along the Hudson River.

According to Herbert Asbury, whose 1928 Gangs of New York is probably the best book ever written on New York crime, ‘Sadie [the Goat] acquired (#litres_trial_promo) her sobriquet because it was her custom, upon encountering a stranger who appeared to possess money or valuables, to duck her head and butt him in the stomach, whereupon her male companion promptly slugged the surprised victim with a slung-shot and they then robbed him at their leisure.’ (For reasons unknown but not hard to imagine, Sadie fell foul of the formidable Gallus Mag of the Hole-in-the-Wall, who bit off her ear, as was her wont. But the story has a happy ending: the two women eventually became reconciled, whereupon gallant Gallus fished into her pickle jar, retrieved the missing organ and returned it to Sadie the Goat, who wore it in a locket around her neck ever after.)

Sophie Lyons, the self-styled ‘Queen of the Underworld’ whose remarkable memoirs are a crucial source of information on Worth’s life, was held by Asbury to be ‘the most notorious (#litres_trial_promo) confidence woman America has ever produced’. She eventually went straight, began writing her salacious, and partly fabricated accounts of New York low-life for the city newspapers, and ended up as America’s first society gossip columnist.

Into this colourful and horrific world, Adam Worth slipped quickly and easily. At the age of twenty, now complete with his own criminal moniker, Little Adam became a pickpocket.

‘Picking pockets has (#litres_trial_promo) been reduced to an art here, and is followed by many persons as a profession,’ wrote the author of Secrets of the Great City in 1868. ‘It requires long practice and great skill, but these, once acquired, make their possessor a dangerous member of the community.’ Sophie Lyons, who became Worth’s close friend and sometime accomplice, described how Little Adam took to the apprentice criminal’s art: ‘Like myself (#litres_trial_promo) and many other criminals who later achieved notoriety in broader fields, he first tried picking pockets. He had good teachers and was an apt pupil. His long, slender fingers seemed just made for the delicate task of slipping watches out of men’s pockets and purses out of women’s handbags.’

As an apprentice pickpocket, Worth found himself in an intensely hierarchical world. The lowest level of pickpocket was a ‘thief-cadger’, inexperienced youngsters often virtually indistinguishable from beggars; of slightly more consequence were the ‘snatchers’ who, as the name implies, made no attempt to avoid detection but simply grabbed and ran, or ‘tailers’, who specialized in extracting silk handkerchiefs from tail-coat pockets. The most developed of the species was the ‘hook’, also known as a ‘buzzer’, for whom picking pockets was an art requiring considerable daring and manual dexterity. Nimble and inconspicuous, Worth began as a ‘smatter-hauler’ or handkerchief thief, but soon the Civil War veteran graduated to become a fully-fledged ‘tooler’, a master of the art of ‘dipping’. Churches were particularly profitable hunting grounds, as were ferry stations, theatres, racecourses, political assemblies, stages, rat fights and any other place containing large numbers of distracted people in close proximity.

While lone pocket-dipping could be profitable, the most successful pickpockets worked in gangs and Worth’s talents ensured that ‘it was not (#litres_trial_promo) long before he had enough capital to finance other criminals.’ Teaming up with some like-minded fellows, Worth now established a dipping syndicate, with himself as principal co-ordinator, banker and beneficiary. It was, proclaimed Lyons, ‘the first manifestation (#litres_trial_promo) of the executive ability which was one day to make him a power in the underworld’, a Napoleon of ne’er-do-wells.

The technique for team-dipping or ‘pulling’, was well established. A prosperous-looking ‘mark’ is selected: he is then jostled or bumped by the ‘stall’; while the mark is thus distracted, the hook (sometimes known as the ‘mechanic’), quickly rifles or ‘fans’ his pockets, immediately passing the proceeds to a ‘caretaker’ or ‘stickman’, who then moves nonchalantly in another direction. Charles Dickens described the manoeuvre in Oliver Twist:‘The Dodger trod (#litres_trial_promo) under his toes, or ran upon his boot accidentally, while Charley Bates stumbled up against him behind: and in that one moment they took from him with extraordinary rapidity, snuff box, note-case, watchguard, chain, shirt-pin, pocket handkerchief, even the spectacle case.’ The ‘mark’, in this case, was none other than Fagin himself, the paterfamilias of dippers.

With his efficient team of purse-snatchers, Worth was fast becoming a minor dignitary in the so-called swell mob, as the upper echelon of the underworld was known, and according to Lyons he soon acquired ‘plenty of money (#litres_trial_promo) and a wide reputation for his cleverness in escaping arrest’. But no sooner had Worth’s criminal career begun to blossom, than it came to a sudden and embarrassing halt. Late in 1864 Worth was arrested for filching a package from an Adams Express truck and summarily sentenced to three years’ imprisonment in Sing Sing, the notoriously nasty New York gaol just north of the city on the banks of the Hudson River.

Worth’s brief incarceration for bounty jumping had not prepared him for the extravagant horror of the ‘Bastille on the Hudson’. In 1825 the prison’s first warden, a spectacular and inventive sadist by the name of Elam Lynds, remarked, ‘I don’t believe (#litres_trial_promo) in reformation of the adult prisoner … He’s a coward, a willful lawbreaker whose spirit must be broken by the lash.’ In 1833 Alexis de Tocqueville had described Sing Sing as a ‘tomb of the living dead (#litres_trial_promo)’, so silent and cowed were its inmates.

Clad in the distinctive striped prison garb instituted by Lynds, Worth was sent with the rest of the convicts to the prison quarries where he was put in charge of preparing the nitroglycerine for blasting. Many years later, Worth recalled how he was instructed by the foreman to heat the explosive when it became cold and brittle in the freezing air. This he did, grateful for the chance to warm his hands, and was lucky not to be blown to pieces for, as he frankly admitted, he ‘never had an idea (#litres_trial_promo) at that time how dangerous it was’. Teaching hardened criminals how to handle nitroglycerine was not, perhaps, the brightest move on the part of the authorities, as Worth’s safe-cracking skills in later years so clearly proved.

The man who had slipped his chains on the Potomac, who had made a craft out of desertion, was not going to suffer the horrors of Sing Sing a moment longer than necessary, even though the prison’s guards, a breed of breathtaking brutality, had orders to shoot anyone attempting to escape. As he worked, Worth calculated the movements of the guards and after only a few weeks of prison life, he slipped out of sight while the guard-shift was changing and hid inside a drainage ditch, which ‘discharged itself (#litres_trial_promo) inside the railway tunnel’. Under cover of night, according to a contemporary, ‘he managed to get (#litres_trial_promo) a few miles down the river where there lay at a dock some canal boats’, in one of which, freezing and covered in mud, Worth hid, and ‘had the satisfaction (#litres_trial_promo) a few hours after that, of having himself transported to New York City by a tug boat, which came up to fetch the canal boat in which he took refuge.’ At dawn, as the tug approached its ‘lonely dock (#litres_trial_promo) far up on the West side of the city’, Worth clambered into the water and swam back to shore. ‘He managed (#litres_trial_promo), although having his prison clothes on, to get to the house of an acquaintance, where he was provided with a suit of clothes.’ He immediately plunged back into the ghastly but protective anonymity of the Bowery.

Worth’s later insouciance when recalling this escape belied what must have been a dreadful, if formative experience. At barely twenty years of age he had seen the worst the American penal system had to offer, and his contempt for authority was formidable. That Worth did not hesitate to plunge into a churning river at dead of night, clad in prison clothes and aware that apprehension might well mean death, reflected both his physical toughness and a growing faith in his own invincibility. So far from being reformed by his brief and unpleasant experience of prison, Worth concluded that the life of a ‘dip’ did not offer sufficient rewards, given its perils, and the time had come to change direction, to up the stakes in his personal vendetta against society. Reuniting with some of his former gang, Worth began to expand his scope of operations to include minor burglaries and other property thefts as well as picking pockets. His word ‘was law with (#litres_trial_promo) the little group of young thieves he gathered around him,’ remembered Sophie Lyons. ‘He furnished (#litres_trial_promo) the brains to keep them out of trouble and the cash to get them out if by chance they got in. Every morning they would meet in a little Canal Street restaurant to take their orders from him – at night they came back to hand him a liberal share of the day’s earnings.’ So far Worth’s activities had gone no further than what might be called disorganized crime. Henceforth he would tread more carefully, delegating often and putting himself at risk only when the rewards, or promise of adventure, were greatest. His strict dominance over the rest of the gang was the first illustration of a power-complex that would grow more pronounced with age. Criminals, it is fair to say, are not the most intellectual of people. Indeed, the class as a whole tends to be characterized by fairly intense stupidity. Worth’s highly intelligent approach to the business, and his ability to get results in the form of hard cash, was enough to ensure the obedience, even the reverence, of his underlings.

Solvent for the first time in his life, Worth’s determination to beat the odds at every level soon led him to New York’s roulette wheels, gambling dens and the faro tables – that extraordinarily chancy game that was once the rage of gamblers and has since virtually disappeared. Betting heavily, in the burgeoning belief that the more he dared the more fortune would smile, he began to live the life of a ‘sportsman’, moving away from the grim Bowery dives to the brighter, more luxurious, but no less dissipated lights of uptown New York and the famously seedy glamour of the ‘Tenderloin’ district.

Worth’s native intelligence was not the only character trait to distinguish him from his fellow crooks. He was also notable for avoiding strong drink, at a time when alcoholism was endemic and heavy drinking virtually obligatory among the criminal classes. Perhaps still more strangely, he refused to countenance any form of violence, regarding it as uncouth, unnecessary and, given his limited physical stature, unwise. Of the 68,000 people arrested in New York in 1865, 53,000 were charged with crimes of violence. Yet Worth made it a rule that force should play no part in any criminal enterprise that involved him, a rule he broke only once in his life. His rejection of alcohol and violence was itself part of a need to control, not just himself, but those within his power. Crooks who drank or fought made mistakes, and for that reason he steered clear of the established gangs, which were often little more than roving bands of pickled hoodlums at war with each other. Worth was not content merely to organize his minions, he needed to rule, regulate and reward them as he clawed his way up through the underworld. A sober, resourceful, non-violent crook marshalling his forces amid a troop of ignorant, drunken brawlers, Worth was also exceptional for the scope of his criminal aspirations, or, to put it another way, his greed. Sophie Lyons took note of his ‘restless ambition (#litres_trial_promo)’ as he began his ascent into the criminal upper classes.

One of America’s senior crooks later recorded that ‘the state of society (#litres_trial_promo) created by the war between the North and the South produced a large number of intelligent crooks’ of varied talents, but in post-bellum New York bank robbers were considered an aristocracy of their own. James L. Ford, an expert on, by participation in, New York’s seamy side, wrote in his memoirs: ‘Such operations (#litres_trial_promo) as bank burglary were held in much higher esteem during the ‘sixties and ‘seventies than at present, and the most distinguished members of the craft were known by sight and pointed out to strangers.’ Allan Pinkerton, the father of Worth’s future adversary, in his 1873 book The Bankers, The Vault and The Burglars, observed that ‘instead of the clumsy (#litres_trial_promo), awkward, ill-looking rogue of former days, we now have the intelligent, scientific and calculating burglar, who is expert in the uses of tools, and a gentleman in appearance, who prides himself upon always leaving a “neat job” behind.’

Worth’s friend Eddie Guerin argued that ‘a successful bank (#litres_trial_promo) sneak requires to be well-dressed and to possess a gentlemanly appearance.’ Sophie Lyons concurred, noting also that a certain amount of professional snobbery pertained in the upper ranks of crime. ‘It was hard (#litres_trial_promo) for a young man to get a foothold with an organised party of bank robbers, for the more experienced men were reluctant to risk their chances of success by taking on a beginner.’

Without success Worth sought acceptance in such established bank-robbing cliques as that of George Leonidas Leslie, better known as ‘Western George’, which was responsible for a large percentage of the bank heists carried out in New York between the end of the war and 1884. Lyons first encountered Worth when he was ‘itching to get (#litres_trial_promo) into bank work’, specifically through her husband, Ned Lyons, a noted burglar. But the veteran crooks turned down all advances from the aspiring newcomer.

Worth needed a patron, someone to provide him with an entree to the criminal elite. He found one in the mountainous figure of ‘Marm’ Mandelbaum.

FOUR (#ulink_1c5aaf24-c8ef-529d-ac1f-72dfef2a5bec)

The Professionals (#ulink_1c5aaf24-c8ef-529d-ac1f-72dfef2a5bec)

CONTEMPORARY WRITERS reached for superlatives when describing Fredericka, better known as ‘Mother’ or ‘Marm’ Mandelbaum: ‘The greatest crime (#litres_trial_promo) promoter of modern times’, the ‘most successful fence (#litres_trial_promo) in the history of New York’ and the individual who ‘first put crime (#litres_trial_promo) in America on a syndicated basis’ are just a few of the plaudits she garnered in a long career of unbroken dishonesty.

Marm’s nickname was a consequence of her maternal attitude towards criminals of all types, for her heart was commensurate with her girth. She was an aristocrat of crime, but unlike the object of Worth’s later affections – namely the portrait of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire – Marm Mandelbaum was no oil painting. ‘She was a huge woman (#litres_trial_promo), weighing more than two hundred and fifty pounds, and had a sharply curved mouth and extraordinarily fat cheeks, above which were small black eyes, heavy black brows and a high sloping forehead, and a mass of tightly rolled black hair which was generally surmounted by a tiny black bonnet with drooping feathers.’

Like Worth, Fredericka had emigrated from Germany to the United States in her youth, arriving ‘without a friend (#litres_trial_promo) or relative’, but far from defenceless. Sophie Lyons, who adored Marm, noted that ‘her coarse, heavy features (#litres_trial_promo), powerful physique, and penetrating eye were sufficient protection and chaperone for anyone,’ adding unkindly (but no doubt accurately) that ‘it is not likely that anyone ever forced unwelcome attentions on this particular immigrant.’

Soon after she got off the boat, the formidable Fredericka had fixed her beady eye on one Wolfe Mandelbaum, a haberdasher who owned a three-storey building at 79 Clinton Street in the Kleine Deutschland section of Manhattan’s East Side. A weak and lazy fellow, Wolfe was ‘afflicted with (#litres_trial_promo) chronic dyspepsia’. A few weeks of Fredericka’s voluminous but easily digestible cooking persuaded him to marry her, and ‘Mrs Mandelbaum (#litres_trial_promo) forever afterward was the head of the house of Mandelbaum’. While still nominally a haberdasher’s, the property on Clinton Street was turned by Marm into the headquarters of one of the largest fencing operations New York has ever seen. She started by selling the ‘plunder from (#litres_trial_promo) house to house’, and in a few years had built up a vast business which ‘handled the loot (#litres_trial_promo) and financed the operations of a majority of the great gangs of bank and store burglars’. Warehouses in Manhattan and Brooklyn were used to hide the stolen goods, while the unscrupulous lawyers Howe and Hummel were employed on an annual retainer of five thousand dollars to ensure her continued liberty, principally through bribery, whenever ‘the law made (#litres_trial_promo) an impudent gesture in her direction’. Most of Marm’s business was fencing, but she was not above financing other crooks in their operations and was even said to have run a ‘Fagin School’ in Grand Street, not far from police headquarters, ‘where small boys (#litres_trial_promo) and girls were taught to be expert pickpockets and sneak thieves’. A few outstanding pupils even went on to ‘post-graduate work (#litres_trial_promo) in blackmailing and confidence schemes’.

Marm Mandelbaum is first listed in police records in 1862, and over the next two decades she is estimated to have handled between five and ten million dollars’ worth of stolen property. Criminals adored her. As the celebrated thief ‘Banjo’ Pete Emerson once observed, ‘she was scheming (#litres_trial_promo) and dishonest as the day is long, but she could be like an angel to the worst devil so long as he played square with her’. As the fame, fortune and waistline of Mrs, soon to be the widow, Mandelbaum (Wolfe’s dyspepsia having returned with a vengeance) grew, so too did the extravagance of her lifestyle and her social ambitions. The two floors above her centre of operations ‘were furnished with (#litres_trial_promo) an elegance unsurpassed anywhere in the city; indeed many of her most costly draperies had once adorned the homes of aristocrats, from which they had been stolen for her by grateful and kind-hearted burglars’. There Marm Mandelbaum held court as an underworld saloniste, and ‘entertained lavishly (#litres_trial_promo) with dances and dinners which were attended by some of the most celebrated criminals in America, and frequently by police officials and politicians who had come under the Mandelbaum influence.’

‘I shall never forget (#litres_trial_promo) the atmosphere of “Mother” Mandelbaum’s place,’ Sophie Lyons recalled wistfully, for here congregated not merely burglars and swindlers, but bent judges, corrupt cops and politicians at a discount, all ready to do business. Such criminal notables as Shang Draper and ‘Western George’ came to sit at Marm’s feet, and she repaid their homage by underwriting their crimes, selling their loot and helping those who fell foul of the law. In a profession not noted for its generosity, Marm was an exception, retaining ‘an especial soft spot (#litres_trial_promo) in her heart for female crooks’ and others who might need a helping hand up the criminal ladder. Marm was an equal opportunities employer and a firm believer that gender was no barrier to criminal success, a most enlightened view for the time and a verity of which she was herself the most substantial proof. She did not, however, brook competition, and when one particularly successful thief called ‘Black’ Lena Kleinschmidt stole a fortune, moved to Hackensack (more fashionable then than now) and began putting on airs and dinner parties, Marm was livid. She was thoroughly delighted when Black Lena was exposed as a jewel thief and jailed after one of her dinner guests noticed his hostess was wearing an emerald ring stolen from his wife’s handbag a few weeks earlier. ‘It just goes (#litres_trial_promo) to prove,’ Marm Mandelbaum sniffed, ‘that it takes brains to be a real lady.’

At the time that Worth was desperately seeking a way into the criminal big league, Marm Mandelbaum was already a legend and arguably the most influential criminal in America. ‘The army of enemies (#litres_trial_promo) of society must have its general, and I believe that probably the greatest of them all was “Mother” Mandelbaum,’ observed Sophie Lyons, who had taken a shine to young Worth and probably introduced him into Marm Mandelbaum’s charmed criminal circle. Worth became a regular at the Mandelbaum soirees, and it was almost certainly under her tutelage that he made his first, disappointing foray into bank robbery. In 1866 Worth and his brother John broke into the Atlantic Transportation Company on Liberty Street in New York and spent several hours attempting to blow open the safe, before leaving in frustration as dawn broke. Lyons recounts his ‘great disgust (#litres_trial_promo)’ at the failed heist. Nothing daunted, after a year of organizing some lesser thefts, Worth, now working alone, pulled off his first major robbery by stealing twenty thousand dollars’ worth of bonds from an insurance company in his home town of Cambridge. Marm Mandelbaum, who could fence anything from stolen horses to carriages to diamonds, obligingly sold them on at a portion of their face value – giving Worth her customary 10 per cent and pocketing the rest. He was hardly made a rich man by the robbery, but it was a start and the minor coup effectively ‘established him (#litres_trial_promo) as a bank burglar’ among his peers. Before long, Worth had gained a reputation as ‘a master hand (#litres_trial_promo) in the execution of robberies’, and stories of his sang-froid began to circulate in the underworld.

Worth seems to have delighted in sailing as close to the wind as he could get, and with every near-escape his contempt for the forces of law and order was confirmed and amplified. As the detectives Eldridge and Watts later recounted: ‘Once, after robbing (#litres_trial_promo) a jewelry store in Boston, this daring burglar slipped out of the front door, only to meet a policeman face to face. Without an instant of tremor, this man of iron nerve politely saluted the officer and stepped back to re-open the door and coolly call to his confederate within: “William, be sure and fasten the door securely when you leave! I have got to catch the next car.” So, indeed, he did, after bidding the officer a pleasant good night, but he hopped off the car a few blocks beyond the store, slipped back stealthily, signalled to his confederate and both escaped with their booty.’

An avid pupil, Worth appears to have found in Marm Mandelbaum both an ally and a role model. The easy way she farmed out criminal work to others, her lavish apartments and social graces, were precisely the sort of existence he had in mind for himself. Above all, it was perhaps Marm who taught the lesson that being a ‘real gentleman’ and a complete crook were not only perfectly compatible, but thoroughly rewarding. Marm’s dinner table offered an atmosphere of illicit luxury, where superior crooks could enjoy the company of men and women of like, lawless minds.

Two of Marm’s guests in particular would play crucial although very different roles in Worth’s future.

The first was Maximilian Schoenbein, ‘alias M. H. Baker, alias M. H. Zimmerman, alias “The Dutchman”, alias Mark Shinburn or Sheerly, alias Henry Edward Moebus,’ but most usually alias Max Shinburn, ‘a bank burglar (#litres_trial_promo) of distinction who complained that he was at heart an aristocrat, and that he detested the crooks with whom he was compelled to associate’. For the next three decades the criminal paths taken by Adam Worth and Max Shinburn ran in tandem. The two law-breakers had much in common, and they came to loathe each other heartily.

Shinburn was born on 17 February 1842, in the town of Ittlingen, Württemberg, where he was apprenticed to a mechanic before emigrating to New York in 1861. Styling himself ‘the Baron’ from early in life, Shinburn later actually purchased the title of Baron Schindle or Shindell of Monaco with ‘the judicious (#litres_trial_promo) expenditure of a part of his fortune’. Aloof, intelligent and insufferably arrogant, the Baron cut a wide swathe through New York low society. Even the police were impressed.

Inspector Thomas Byrnes of the New York Police Department considered him ‘probably the most expert (#litres_trial_promo) bank burglar in the country’, while Belgian police offered this description of the soigne, multilingual felon: ‘Speaks English with a (#litres_trial_promo) very slight German accent. Speaks German and French. Always well dressed. He has a distinguished appearance with polished manners. Speaks very courteously. Always stays at the best hotels.’ Shinburn’s looks were striking; he had ‘small blue penetrating (#litres_trial_promo) eyes, long, straight nose, moustache and small imperial, both of brownish colour mixed with grey, moustache twisted at the ends, pointed chin … at times wears a full beard and sometimes a moustache and chin whisker, in order to hide from view the pronounced dimple in chin.’ His numerous encounters with the law and a youthful taste for duelling had left him with numerous other identifying features. After one arrest, a police officer noted these with grisly exactitude: ‘on back of left (#litres_trial_promo) wrist … pistol shot wounds running parallel with each other and near the deformity in right leg … pistol or gunshot wound on left side … several small scars that look like the result of buck shot wounds; scar on left side of abdomen, appearing as though shot entered in the back and came through …’ Shinburn’s fraudulent aristocratic claims were full of holes, and so was the rest of him.