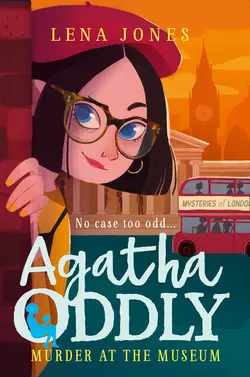

Murder at the Museum

Murder at the Museum

Lena Jones

A second mystery for thirteen-year-old Agatha Oddly – a bold, determined heroine, and the star of this stylish new detective series.Agatha Oddlow’s set to become the youngest member of the Gatekeepers’ Guild, but before that, she’s got a mystery to solve!There’s been a murder at the British Museum and, although the police are investigating, Agatha suspects that they’re missing a wider plot going on below London – a plot involving a disused Tube station, a huge fireworks display, and five thousand tonnes of gold bullion…

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2019

Published in this ebook edition in 2019

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Children’s Books website address is

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Text copyright © Tibor Jones 2019

Cover design copyright © HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Cover illustration by Alba Filella

Tibor Jones asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008211899

Ebook Edition © March 2019 ISBN: 9780008211905

Version: 2018-12-12

For Lizzie and Hannah

Contents

Cover (#u12fc5da0-cbd7-53ff-9b6f-d0090600fcfa)

Title Page (#u91fa9922-727c-5658-8d70-5bf4361e9c41)

Copyright (#ubb6356e4-8175-58d7-8df4-ea519ea8897a)

Dedication (#ued77156c-d6b7-5781-a633-4dacad017dd7)

1. Rule Breaker (#u6e024477-c1e6-51e5-a130-00ef4c562178)

2. Work Placement (#u57bfad6a-d1d6-5397-a014-1f79b1089d8b)

3. Crawl Space (#u1eb2c88e-7180-5a56-835d-1a851847b50d)

4. The Black Bamboo (#u53e2ff4f-01d4-575c-a09e-ceabe7eb228f)

5. The Sinkhole (#litres_trial_promo)

6. The Forgotten Underground (#litres_trial_promo)

7. New Girl (#litres_trial_promo)

8. Homework (#litres_trial_promo)

9. Smugglers’ Dock (#litres_trial_promo)

10. Found Out (#litres_trial_promo)

11. Running out of Time (#litres_trial_promo)

12. Land of Gold (#litres_trial_promo)

13. A Cold Dip (#litres_trial_promo)

14. A Sweatshirt in the Works (#litres_trial_promo)

15. Rescued! (#litres_trial_promo)

16. Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Onomatopoeic Cipher (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

Read all the Agatha Oddly adventures (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

(#ulink_2262b26c-6745-5480-b8e7-fd08a85f0883)

‘That film was crazy!’ says Liam with satisfaction as we step out of the Odeon.

The evening air is pleasantly warm and there are still hordes of people milling around in Leicester Square. We navigate through them. Liam turns his phone back on, while I fish out the last scraps of popcorn from my box. We’ve just seen the latest crime thriller – Midnight Delivery – and can’t wait to point out all its plot holes.

‘I knew it was the window cleaner,’ I say. ‘He was far too nosy. And as for the detective – he was soooo slow.’ I laugh. ‘Brianna would’ve had a field day! Why did she say she couldn’t come?’ Liam is my best friend, but Brianna is a close second. The three of us hang out together a lot.

‘Oh … I think she had homework,’ he says.

I chuckle. ‘That figures. One full day left of the holidays and she’s finally getting round to it.’ Liam and I always get our schoolwork done at the start of the holidays, but Brianna likes to leave it until the last possible minute. I once saw her writing in an exercise book while she was walking down the street to school.

Liam’s too busy looking at something on his phone to reply, so I wander over to a bin and dump my empty popcorn box. On a pavement board close by is a poster, with the words LORD MAYOR’S FIREWORKS! in big letters at the top. I scan the details. The extravaganza – with ‘over 15,000 fireworks!’ – will take place beside the Thames, on Sunday.

‘Isn’t September a bit early for the Lord Mayor’s fireworks?’ I say as Liam comes over. ‘Don’t they usually do them in November – around Guy Fawkes Night?’ I think some more. ‘And I’m sure they’re usually on a Saturday.’

He doesn’t answer my question, but says, ‘Check this out,’ and he holds out his phone, so I can see the screen. It’s a news alert:

BREAKING NEWS: Murder at British Museum

I stare at the red letters for a moment, feeling a familiar excitement. It’s been five weeks since I solved the case of the red slime that had polluted London’s water supply, and I’m itching to get going again. Things have been too quiet with no cases to solve, so I haven’t been enjoying my summer holidays as much as usual.

I take his phone and click on the link. There’s not much information to go on yet:

A member of staff has been stabbed to death shortly after closing time this evening at the British Museum. Police have yet to release the name of the staff member, who is believed to be an attendant who may have disturbed an intruder. A museum exhibit is said to be missing from a display case.

I feel a surge of happiness. ‘Finally, an actual case!’ I catch Liam’s eye as I hand back his phone. ‘Come on – we need to investigate!’

He scrutinises me. ‘Agatha, tell me you’re not actually pleased that someone’s been murdered …?’

My cheeks turn red; hopefully he won’t have noticed. ‘Of course not.’ I study my nails: currently black with silver stars. I’m especially pleased with the stars, which have come out just right.

‘Anyway,’ he continues, ‘it’s a murder investigation – you won’t be able to just wander in there.’

This is the type of challenge I live for. ‘Of course I will. “No Case Too Odd”, remember?’ I say, reciting the Oddlow Agency’s motto. I’d got sick of people making fun of my surname, Oddlow (Oddly … Oddball … Oddbod … Odd Socks …) so I’d decided to put a positive spin on it.

‘But this doesn’t even seem especially odd …’ he says doubtfully.

Not wanting to waste time, I grab him by the arm and start to stride through the Leicester Square crowds, in the direction of the Tube. Liam stumbles after me, reading the report on his phone.

‘It says they’ve put the museum on lockdown, so nobody can get in there – not even you.’

‘Ah, but who said I was going to use the front door?’ I look back at him, raising an eyebrow. With my free hand, I touch the place below my neck where my mum’s black metal key is hanging from a silver chain. It’s not just a trinket: it belongs to a secret organisation called the Gatekeepers’ Guild, and it gives access to underground passageways all over London.

Liam frowns. ‘You’ll be in serious trouble if Professor D’Oliveira finds you using the tunnels before your Trial begins.’ The professor is my contact at the Guild. If I want to become an agent, or Gatekeeper, like my mum (and I really, really do), I have to pass three tests that make up the Guild Trial.

I sigh. ‘I know … but I didn’t expect it to take this long to get started! I’ve been waiting five weeks already!’

‘Come on, you know how gutted you’ll be if they catch you – and the professor says you can’t take the tests and become a Gatekeeper if you break the rules.’

I roll my eyes. ‘But they’re not going to notice if I use the key just this one time, though, are they? I’m sure I can dodge them.’

Liam shakes free of my grip.

‘Aren’t you coming?’ I ask, in surprise. Liam normally jumps at the chance of some excitement.

‘Agatha, you’re my best friend – but you’re talking about interfering with a crime scene and risking your chances of becoming an agent.’

I decide to focus on his first objection, so I ignore the second. ‘I’m not going to interfere,’ I say indignantly. ‘I’m just going to look for clues …’

‘… And potentially get in the way of the police, who are themselves looking for clues.’

I pause for a moment, wondering whether to try and win him round. But he’s wearing his determined look.

‘OK,’ I say. ‘Don’t worry about it – you can go and find out what they’re saying about the murder on the news. We can compare notes when I see you on Thursday in school.’

‘Right … just – be careful, though.’

‘Oh, it’s OK – I’ll just dig a tunnel using a spoon,’ I say, referring to one of our favourite films.

‘So long as you have a plan,’ he says with evident sarcasm (spoilt by the fact he’s obviously trying not to laugh when he says it).

‘I always have a plan,’ I reply.

‘If there’s any more info on the news, do you want me to leave you a note?’ he asks.

‘Oh, I forgot to tell you – Dad found the loose brick in the wall, so we can’t use it for messages any more. He’s cemented it in!’

‘Seriously? Couldn’t you have stopped him?’

I shrug. ‘He’d “fixed” it before I got the chance. We’ll just have to find a new way of sharing information.’

Liam shakes his head sadly. ‘I loved our brick,’ he says, as if we’ve lost a dear friend.

I shrug again. ‘Look, I’ve got to be off, OK? I’ll see you at school on Thursday,’ and I give him a quick wave then jog the short distance to the Tube station.

On the platform, with five minutes to wait for the train, I feel the adrenaline start to mount. Tonight I’m no longer Agatha Oddlow, scholarship student at a school for privileged kids, but Agatha Oddly, private investigator, named after the world-famous crime writer Agatha Christie.

As the train carries me along, I settle into the rhythm and plan my entrance into the museum. I have a useful ability to ‘Change Channel’ – switch off from whatever’s going on so I can access other parts of my brain. I close my eyes and use this technique now, to focus on the task ahead. I’ll be needing a costume and a convincing reason for being at the museum after hours.

By the time I get back to Hyde Park I’ve worked it all out, and I can’t wait to get started.

As I hurry along the path beside the Serpentine lake I automatically glance at the benches to see if my old friend JP is there, but then I remember JP’s no longer homeless, so he doesn’t live in the park any more. He’s managed to get himself a job, and it even comes with a flat he can rent cheaply. I’m really pleased for him, but I miss our daily chats.

As Groundskeeper’s Cottage comes into view, I force myself to focus on my plan. The first thing I need to do is be seen by my dad, Rufus, so that he thinks I’m going to bed for the night. Also, the popcorn already seems like a long time ago, so I should probably make myself a sandwich before I set out.

‘Hey, Dad!’

‘Hi, Aggie. How was the film?’

‘So terrible that it was brilliant – really funny!’ I go over to where Dad is sitting at the kitchen table, studying some landscape designs for the park, and give him a peck on the cheek.

‘That’s good. Have you eaten?’

‘Only some popcorn,’ I admit. (Dad hates it when I skip meals.)

‘You should make yourself a sandwich,’ he says.

I grin. ‘You read my mind!’

I set to work, spreading first butter, then peanut butter, then a layer of salad cream. It’s a combination I haven’t tried before, but I’m always keen to experiment. I did over-experiment at one point last term, when I attempted to create a masterpiece from a French cookery book. It was disastrous – and I lost some of my confidence – but I’m over that now, and open to new culinary experiences again.

As I stick the two pieces of bread together, I start to go over the details of the plan in my head. I’ll need some keys from Dad’s collection – he has them to open gates and gratings all over Hyde Park. But Dad derails my train of thought—

‘I won’t be around tomorrow morning, by the way.’

‘Oh? How come?’ I look around for the bread knife. Sandwiches always taste better when you cut them into triangles.

‘Yeah, I … um, I have a meeting with an orchid specialist from the Royal Horticultural Society.’

Something about Dad’s tone makes me turn round and look at him.

‘An orchid specialist?’

‘Yes … a very prestigious one … and she’s only free first thing. So I won’t be around when you get up.’

He clears his throat and goes back to studying the plans in front of him, in a too-concentrated way that seems a bit forced. But I don’t have any time to worry about what Dad may be up to – I have to get going if I want to inspect the crime scene before the police remove all the evidence.

‘OK, I’m going up.’

Dad glances at the clock. ‘It’s only eight thirty. Bit early for you, isn’t it?’

‘It’s a well-known fact that teenagers need more rest than adults.’

‘That’s my line,’ he says, frowning. ‘What are you up to?’

I put on my most innocent expression. ‘Nothing. I’ve just got some reading to do for English, and I want to look over the essays I did at the start of the holidays.’ I scoop up my plate and make for the door. ‘Don’t stay up too late, Dad. See you in the morning!’

‘OK … night, love.’

I stop on the first-floor landing and creep into Dad’s room, where Oliver the cat is curled up on the bed. Dad has a rule about not letting cats on beds, but that never deters Oliver. Slipping the set of keys I need from a hook on his crowded key rack, I place them in my pocket, then start up the next flight of stairs, wolfing down my sandwich on the way. It tastes foul and I make a mental note not to try this particular combination again. I set the empty plate down on my bedside table and look around with satisfaction at my room. It’s in the sloping attic space at the top of our cottage and is packed with interesting objects and artefacts, including shells, feathers and fossils, newspaper clippings and elaborate disguises. There’s a porcelain bust of Queen Victoria that I found in a skip, plus a chart of eye colours with codes for each shade, which I’ve memorised. A portrait of my favourite crime writer, Agatha Christie, hangs in pride of place above the bed, and there’s a smaller portrait of her most famous character, Hercule Poirot, on the back of the door.

For a moment, my thoughts turn back to the Guild – and, more importantly, the Trial. I’ve been thinking about it all summer, like a song I can’t get out of my head. It makes me nervous, knowing that the first challenge could begin at any moment, even in the middle of the night, and I have to be ready for it. I guess that’s the whole point – if you can’t be ready at any moment, to act without warning, then you can’t be a member of the Guild. But I do wish they’d get it over with.

I take off my red beret – my best-loved item of clothing – and place it carefully in its box. Then I go over to my two rails, where I keep all my clothes and costumes, and start to rummage for the items I need.

Luckily for me, I’ve already made some notes in my head on the British Museum from my previous visits there. I close my eyes and Change Channel to reach the area where the relevant information is stored. It looks like a series of old-fashioned filing cabinets. I access the one for uniforms and flip through the handwritten cards inside, until I reach M, for ‘Museum’ – then I select subcategory B, for ‘British’. All the British Museum uniforms I’ve observed have been filed away here, each as an imaginary photograph. I want to get in as an attendant – it’s the most convincing role for someone of my age – and the uniform I call up is a simple one: black trousers with a white shirt.

Flicking through the garments hanging from my clothes rail, I pick out a suitable shirt and some trousers. From a box underneath I take a black faux-leather belt and a pair of Doc Martens boots with thick rubber soles that give me a few extra centimetres. They were a brilliant find in a charity shop and I love them. I get changed quickly, removing my knee-length red gingham shirt dress (one of my favourites, also from a charity shop) before pulling on the trousers and shirt. Accessories come next – a work pass on an extendable lanyard which I attach to my belt, and a very basic work badge to pin to my chest, which claims that my name is ‘Felicity’. This is the name I use on social media – after detective Hercule Poirot’s secretary, Felicity Lemon. Finally, I tie my hair back in a bun, and for extra camouflage add a pair of thick-rimmed glasses (which are stored in a chest of drawers full of similar accessories – false eyelashes, sunglasses, headscarves, fake scars, bushy eyebrows …). I slip the keys into my pocket, along with a small notebook and pen, an LED head torch, a lock-picking kit, and a plastic vial containing a clean cotton bud – an essential part of any detective’s kit. My pocket is now bulging, but I don’t want to complicate things by taking a bag with me that I might have to abandon somewhere.

Everything done, I look myself over in the mirror.

Pretty convincing.

I don a long plastic mac over my outfit to keep it clean. This monstrosity – the sort of shapeless cover-up sold to tourists who arrive in Britain unprepared for the rain – is not an item I would ever normally wear in public. But needs must.

‘See you later, Mum,’ I tell the photo of my mother that I keep by my bed. She’s wearing a long, flowing skirt, big sunglasses and a floppy hat. I like her style – comfortable but chic. She’s standing astride her bike, which is piled high with books, as usual. The police said it was the books that made her bike difficult to steer – and that was why she’d lost control in an accident with a car and died. But I don’t believe that. For a start, I found her bike, and it didn’t have a scratch on it. If I can join the Gatekeepers’ Guild, maybe I can find out what she was investigating when she died, and it might give me some answers.

Deep breath now – here comes the difficult bit.

I turn my bedroom lights off. If Dad comes up to see what I’m doing, I don’t want him to think I’m awake. Then, making my way across the cluttered room by memory, I climb on to my bed. The evening sky is overcast, but there’s just enough light for me to make out the rectangle of my skylight. I open this now, grab on to the edge, and haul myself up and out, so that I’m sitting on the roof, straddling the ridge.

I wait for a moment. I like it up here – there’s a gentle breeze stirring and, now that summer’s coming to a close, the night is neither too warm nor too cold. Off in the distance, at the edge of the park, I can see the twinkling lights of Kensington. I divide the mission up into phases in my mind: stage one – get away from the house undetected by Dad; stage two – crawl through a long, uncomfortable passage; and stage three – gain entry to the museum. I take a deep breath.

Right: it’s time to go.

I ease myself off the ridge and slide down the tiles to the edge, where I cautiously stick my right foot out into space until it makes contact with the nearest branch of the ancient oak tree. The left foot joins it. Next comes the scariest moment, when I push off from the roof and have to trust the rest of my body will get across safely … It does, of course – I’ve been climbing up and down this tree since I was ten. With my arms round the trunk, I feel for my next foothold and make my way down to the ground. I’m glad I thought to wear the raincoat, or my clean white shirt would be covered in moss and lichen by now.

I jump down on to Dad’s immaculately maintained lawn, keeping the oak tree between me and the kitchen window. Dad mustn’t see me. Then, taking a deep breath, I run through our gate and off across the park, into the night.

Stage one – complete.

(#ulink_37a99af8-e321-5fc6-adea-c15696a152a0)

To reach the underground passageways governed by the Gatekeepers’ Guild, first I have to open a grating beside the Serpentine. I step down the short ramp that leads to the dark, caged-off hole and, when I reach the grating, I fish out Dad’s keys and select the correct one. I insert it into the lock – but for some reason I can’t get it to fit neatly and turn. I struggle with it for a while before giving up and sitting down on the dewy ground. What now?

I hear Hercule Poirot’s voice in my head, with its familiar Belgian accent: ‘Venez, Mademoiselle Oddlow, we won’t let un petit lock stop us at the first ’urdle, n’est-ce pas?’

Poirot may be a fictional detective, but he’s my inspiration. Why won’t the key turn? Maybe something’s stuck in the mechanism. I get up and inspect the padlock. Sure enough, there’s a pine needle jammed inside. I form pincers with my thumb and forefinger and manage to remove the tiny obstruction. Then I try the key again. This time it turns, and I swing the grating open and crawl through, pulling it shut behind me.

I shiver, remembering the last time I was down in this dank passageway. The tunnel had been full of toxic red algae, so Liam and I had worn face coverings to filter out the fumes. Even without the stinking slime, it isn’t exactly welcoming.

I take the head torch from my pocket, turn it on and slide the harness over my head. The bright bulb illuminates a dirty concrete path. There’s a crumbling brick roof that’s far too low for comfort, even for a thirteen-year-old of average height, and I have to crouch. I sigh and begin my uncomfortable passage through the long tunnel. It stretches downwards, taking me ever deeper beneath the ground.

Despite the vast amount of earth above my head, I divert my thoughts away from images of the ceiling caving in. My palms and knuckles keep scraping on the stone and brick, and my neck aches badly from having to keep my head bent at an awkward angle. My progress is further hampered because I have to stop every so often to rub my aching leg muscles, which aren’t used to staying bent for so long.

I don’t realise I’m holding my breath until the corridor opens out into a wide cavern, and I find I’m gasping – dragging in oxygen as if I’ve been under water. I laugh at myself – I’ve made the whole journey harder by tensing up and holding my breath! I stretch my back out and give myself a shake. It’s such a relief to be able to stand upright.

Stage two – complete.

On the far side of the cavern there’s an iron door covered in rivets, like the entrance to an ancient castle. It’s so rusty that it’s almost the exact shade of the surrounding bricks, making it nearly invisible. Now for the next key: the one I promised Professor D’Oliveira I wouldn’t use.

I pull the silver chain out from the collar of my shirt and insert the large metal key into the lock. Mum’s key. For a moment, I picture her turning it in secret gates and doors. I feel such a strong link to her when I use it. It turns soundlessly in the well-oiled mechanism. I leave my head torch on the ground, then I push the door open a crack – enough to check for guards, before stepping inside and pulling it closed behind me.

That was way too easy: the Gatekeepers’ Guild really should increase their security.

I head down a long, well-lit corridor with a plush, red carpet. After a couple of hundred metres, the carpet gives way to stone as I approach the bike racks. There are hundreds of bicycles here, of all sorts, from high-tech mountain models and off-roaders, to older, more upright models. The Guild own mile upon mile of tunnels, and they prefer to ride through them wherever possible, to save energy and time. For a moment, I try to imagine what type of person owns each model. I spot a large, unwieldy black mountain bike and picture a very severe man in a dark suit. I fix on another one – a pink sparkly, Barbie-doll type – and decide it has probably been borrowed by a parent from their child. I know which one I’m going to use. It belonged to my mum: a baby-blue town bicycle with a basket. The professor promised to keep it here for me.

But it’s missing.

I go through the racks, twice, but it’s definitely not here. Has someone taken it? Or is it just being stored somewhere safe? I make a mental note to ask the professor about it. I feel a pang at the absence of what feels like a piece of my mum. It’s only a bicycle, I tell myself. I consider taking another one instead – but that feels more like stealing. I’ll just have to jog.

I start to run slowly, building up speed until I’m making good progress along the main tunnel. The ground is fairly smooth here – worn down, I suppose, by years of use by the Gatekeepers. At last I spy a smaller passage off to the right, with a sign for the British Museum. I turn into it and soon reach a full-height metal gate.

Once again, my magic key opens the lock. I step through, close the gate behind me, and abandon my hideous raincoat at the bottom of a short set of stone steps leading up to the museum. At the top, another turn of the key lets me through a wooden door.

I’m in a tiny room that holds nothing but a long staircase, leading upwards, and I jog up them with ease. My fitness levels are pretty good these days as I’ve been working out a lot over the summer. Before too long I reach what I gauge to be the ground floor. There’s a door with a grimy window. I give it a wipe with my hand, and see I’m just off a large corridor. There’s no one about, so I slip through the door and easily find my way into the main foyer of the museum.

Stage three – complete.

I know the layout of the British Museum from the many times Dad has brought me here over the years to see the different exhibits, and I walk quietly but confidently through the public section of the building. I meet no one on the way, but I can hear voices as I approach the area where the murder took place. I walk towards the doorway, careful not to draw attention to myself. As I step over the threshold, I take out my notebook and pen and stand poised at the first display cabinet, as if I’m taking notes on the exhibits. If I’m spotted, I’ll need to have a good cover story.

Despite my careful planning, I freeze at the sound of a voice quite close, convinced I’ve been seen. But they’re not talking to me.

‘So, the piece that’s missing is a clay mug?’

I glance over at the speaker. It’s a female police officer, with light-brown hair tied back in a ponytail. She’s writing in a notebook.

The person she’s addressing is a man of about thirty-five, with closely cropped hair and round glasses, which he keeps pushing up his nose. He’s clearly anxious – I can see beads of sweat on his forehead. This nervousness, combined with the expensive cut of his suit, suggests he’s probably a senior official at the museum. No doubt he’d be feeling distressed that one of the museum attendants, a member of his staff, has died at work. I can’t imagine how hard it would be to feel responsible for something like that.

He clears his throat. ‘That’s right, yes. It’s a strange choice for a burglar.’

‘How so?’

‘Well, you see this piece, right beside the gap?’

I crane my head to get a look but I’m too far away.

‘With the lion’s head?’

‘That’s right. Well, that is a very fine example of Etruscan pottery. It’s almost priceless. The clay cup … well, that’s not worth much.’

‘So you’re saying …’

‘I’m saying it’s odd that a burglar would kill for the clay cup. But perhaps he took the wrong artefact …? I still can’t believe one of our own museum attendants is dead!’

‘I’m so sorry. This must be very upsetting for you. I’ll try not to keep you much longer. But the more help you can give us, the sooner we can catch the culprit.’

‘I understand—’

‘Hey! Where did you come from?’ I jump at the voice in my ear and turn to face a male police officer. He frowns. ‘You aren’t supposed to be here.’

Rookie mistake: I should have kept checking behind me, instead of becoming mesmerised by what was going on in front.

‘Oh no,’ I say, in an eager voice, ‘I am meant to be here, Officer. I’m here on work experience, and I’ve been in the stores, cataloguing the exoskeletal organisms.’ I have no idea if such a collection exists, but I’m hoping to blindside him with long words.

‘So what are you doing here?’ He gestures to the display case. I haven’t even taken in the exhibits, but I glance down and see they appear to be fertility statues. I think fast.

‘Oh – I finished my work experience tasks for the day and my manager said I could do some of my own work, on my school project – “Fertility rituals of the ancient worlds”.’

‘Did you not hear the announcement to evacuate?’

I shake my head, wearing my most earnest expression. ‘No, I haven’t heard anything. Why … has something happened?’

‘Surely someone told you this part of the museum is off-limits?’ He seems entirely bemused by my presence.

I shake my head again. I need to distract him with a change of topic. Discreetly, I take in as much information as I can, my eyes flicking over his form. There’s not much to go on, because he’s in uniform, but I do find a few clues.

‘Do you like dogs?’ I say, thinking on my feet. ‘I love them!’

His eyes light up. ‘I love dogs too! I have four of my own,’ he says proudly.

‘You’re so lucky,’ I say. ‘I’d love a dog, but my dad won’t let me have one.’

His radio crackles and a female voice comes through, issuing instructions. ‘Oh, that’s for me,’ he says. ‘Just get your things and go home.’

‘OK … thanks! I hope my school teacher won’t mind too much if I’m late with my project.’

‘Can’t help you there, I’m afraid. Don’t forget your coat,’ he says, pointing to a door marked STAFF ONLY. As long as he’s watching, I can’t head back the way I came in, so I obediently go the way he indicates.

It takes me into another hallway, with another set of stairs leading down. I run down to the basement, wondering if there might be some way back to the tunnel from here. At the bottom there’s a door.

I push it open.

(#ulink_7586f55c-04b1-5e86-b641-8c2152ffdc48)

I step inside and quickly shut the door behind me. I’m in darkness and I fumble for a moment before finding the light switch. My nostrils fill with the smell of damp stone.

The single bulb flickers and then comes on; it sheds barely enough light to see by, and casts weird shadows around the room.

The basement itself is ordinary enough – concrete floor and ceiling, with three walls also made of concrete. The fourth wall, facing me, is made of brick and looks older. There are several sets of metal shelves against the walls, stacked with a variety of cleaning products – sponges and mops, buckets and basins, bottles of bleach and disinfectant. There’s only one other object in the room, over in the far corner.

It’s as big as a bear, and so blackened with age it takes me a minute to work out what it is – a boiler, old and long retired. It was probably left here because it was too much trouble to dismantle it and lug it up the narrow stairs. The squatting lump of metal is knuckled with rivets and valves. There are several water pipes leading up from it, but these have been chopped off, and now stop short of the ceiling.

I sniff the air. Not just damp, but the scent of bleach. This could be from the army of mop buckets down here, but the smell is strong and fresh. By the light of the single, naked light bulb, I look around at the floor, then crouch to run my finger over it. Dust – lots of it.

Over in the corner, by the old boiler, the floor is darker. I walk over. Yes – the concrete here has been scrubbed recently and is still damp. Why would someone clean this patch but not the rest of the room?

In my mind’s eye, I conjure up a Polaroid camera. It appears in front of me, hovering in the air. I hold the imaginary camera steady, and start to take some snaps of the room. Each photo scrolls lazily out of a slot on the camera and develops from black to a colour image. When I’ve taken enough pictures, I file them away in my memory.

Now for my next job. I fish out the plastic vial and use the cotton bud to swab the floor. I could be wrong, but I have a funny feeling about this wet patch. So I place the swab safely back inside the vial for analysis in Brianna’s secret lab.

Then I step up to the disused boiler. It’s covered in dust and clearly hasn’t been used in a very long time. The pipes are cut off, so it can’t have leaked. Why would anyone need to clean up here?

Peering into the darkness behind the boiler, I can’t make anything out. On my keyring I have a tiny torch, which my dad gave me last Christmas as a stocking filler, so I point it into the darkness. There isn’t much there, although … I peer more closely. Yes! It looks like there could be a hole in the wall! I can’t see into it from this angle, but the back of the boiler is completely free from dust. It seems as though someone’s been crawling around in this area.

There’s only one thing for it. Clamping the torch between my teeth, I shuffle forward and crouch down until I’m fully enclosed inside the cramped space. I can see it now, just as I suspected – a hole in the brick wall, big enough for a grown human being to fit through. Looking down at the dirty floor, I can just make out a boot print. Someone has definitely been through here recently!

Steeling myself, I start to crawl forward. My keyring torch doesn’t do much to illuminate the space, but by moving the beam around I can see tunnel walls opening up. I wish I hadn’t left my powerful head torch in the cavern under the Serpentine.

As I go through the underground passage, the brick surface changes, first to something like concrete, then to a material resembling bedrock, chipped away roughly with a chisel or a small pickaxe. There are no signs of activity here, and it’s completely silent. I continue, slightly crouched, but hurrying along.

After about thirty metres, the corridor begins to slope down and, a little further on, the space starts to open out once again. Here, the walls are lined with brick, as the rough-hewn tunnel gives way to a carefully built structure, like a Victorian sewer. Thankfully, this is much cleaner and drier, though!

I carry on, now able to stand up fully, holding the torch in front of me like a miniature shield. Its beam isn’t strong enough to fully light the way, and the area ahead looks especially dark and unwelcoming. Until this moment, I’ve been caught up in the chase. Now, though, I’m suddenly aware of my own smallness. What, or who, might I find down here?

I hesitate. I think of Dad, and my cosy room under the eaves of the cottage.

Then Hercule Poirot speaks to me in the darkness: ‘Ma chère Agathe, you have stumbled upon un petit mystère, non? You are not going to turn back now?’

Too right I’m not. I push on.

Twenty more steps and the space opens out into an even wider passage. Here, my tiny light seems brighter than it did in the brick section, because the walls around me are lined with white ceramic tiles which despite being grimy still manage to reflect a little of the beam back towards me. The pale expanse is broken up by bands of tiles in a dark colour, burgundy perhaps, or purple – it’s hard to tell in this light under the layers of dirt. But there’s something very familiar about them. It takes me a while to realise what it is, out of context as they are.

Of course! These are the tiles used across London to line the walls of Tube stations! In the days when many Londoners couldn’t read, the patterns were used to signal the different stations.

Over the last few years, I’ve travelled through almost all the stations on the Tube map, except for some of the ones further out. I’ve taken mental pictures of all the tile designs, and I call them to mind now. The pictures appear in front of me as Polaroids, stuck with brass pins to a corkboard that’s hanging on the wall.

I check through all of them quickly, but can’t identify the particular arrangement of tiles I’m seeing now – the two burgundy bands separated by a band of white. I turn away from the images.

This is a conundrum – a Tube station which is not a Tube station, right in the heart of London.

I walk a little further, my footsteps echoing back at me. Glancing down, I see dust swirling around my feet. The tunnel is thickly carpeted in a grey lint, which has settled and collected over many years. But I’m not the first person to walk here recently. There are footprints, though how many sets it’s difficult to tell because they keep to a track, like when someone walks through snow along the same path that someone else has already trodden down. I think about walking in that track myself, to disguise the fact I’ve been here, but it’s too late – I’ve already left my prints behind me. A little further down the corridor, I get my first confirmation that this underground building is indeed a Tube station, albeit an unused one – a faded, much-torn poster advertising Ovaltine is pasted to a curved billboard set into the wall.

The poster looks old – very old by the style of font and the watercolour illustration of a woman holding a steaming mug in front of her. If I had to guess, I’d say it’s from the 1930s or ’40s, and was put up sometime during the Second World War. But why is it still here? Why was this Tube station abandoned? I walk on, turning this way then that through the empty tiled corridors, and find my answer.

I’ve stepped out on to a platform. And there, on the wall across from me, is a faded sign, which reads: BRITISH MUSEUM.

It’s the disused British Museum station! It’s been closed for decades. The people who ran the Tube back then decided that there weren’t enough people using it. It wasn’t even close to the museum. I know that it used to be a stop on the Central line (that’s the line marked red on Tube maps), which for the most part draws a neat line through the middle of London. I wonder whether the Central line trains pass through this station now or just bypass it, going down another nearby tunnel.

As if on cue, I hear a distant, rattling rumble – the familiar sound of a Tube train passing by.

I’ve always wanted a chance to visit some of the abandoned stations – but I don’t have much time to think about that now, because it’s getting late and there’s a murder to solve – and if Dad has realised I’m away from home, I need to be getting back sooner rather than later.

I search quickly around the platform and find more clues – tiles wiped clean of dust through contact, and, there, a little further along, a dust-free space on the ground, where something was obviously being stored, though it’s gone now.

The space is large and roughly rectangular. It doesn’t give much of an idea as to what might have been there. When I reach the edge of the platform, I bend down and shine my light into the dark passage. I half expect to see that the old tracks have been ripped up, either to stop trains from passing this way, or so that the metal could be recycled, as happened with many of the city’s metal gates and fences during the Second World War. But, as I shine my torch down into the dark canyon, two gleaming bands of silver throw the beam of light back at me. The old rails are not only still in place; they are polished so highly that there can be no mistaking it – trains have passed through here recently, and often.

Hmm … how can that be? I’ve now heard three trains pass by and not one of them has come through. Perhaps they use this tunnel to store trains when they’re not in service. Or maybe it’s used to store repair vehicles on the tracks. Or could it be a bypass tunnel, which allows trains to pass while another sits idle?

I finish looking around the station, taking mental photos of everything as I go. I wish I had a real camera, so I could get some actual pictures of the boot prints marking the dust around me, but my own memory will have to suffice. I stare at some of them for longer than usual, to make sure that the images are well developed.

Finally, it seems there’s no more for me to investigate down here. I could go back up to the British Museum the same way I got down, but the police investigation is well established up there. If I make another appearance, I’m bound to be spotted again, and this time the police might be suspicious. I’m glad I brought my Guild key.

Walking to the far end of the platform, I hop down on to the tracks – and just in time too: I hear the voice of a man, arriving on the platform behind me. Hurriedly, I turn off my torch.

‘Did you remember my five sugars?’

I crouch and hold very still.

Another man responds: ‘Dunno. I just shovel them in.’ So that’s two men, at least.

‘Jeez, Frankie – you know I can’t drink it when it’s not sweet enough.’

‘I’m just amazed you’ve got any teeth left.’

They laugh. I can’t hear any other voices joining in, but, although it’s a relief they’re alone, two’s more than enough to worry about. I begin to shuffle quickly towards the tunnel, but I lose my balance for a moment and my foot thuds against the metal of the train tracks.

One of the men speaks: ‘What’s that?’

‘What?’

‘I heard a noise.’

‘Probably one of those mice that live along the rails.’

‘Sounded like a pretty big mouse.’

I hear footsteps approaching and flatten myself against the side of the platform as much as possible. Crouching in the shadows, I hope I’m nearly invisible.

A torch is shone along the tracks. It gets worryingly close to me, reflecting in the toe of my boots. I really shouldn’t polish my footwear if I’m going to wear it for undercover work. Has he seen me? I hold my breath and close my eyes. I’m clutching my front-door keys, the only potential weapon I have to hand, but I don’t fancy my chances if I have to rely on them to defend myself.

‘Nothing there,’ he pronounces, turning and heading back to his mate.

‘What time did you say it’s due?’ asks the other one.

‘In the next five or ten, I reckon – if they don’t have to stop in a side tunnel on the way.’

While they’re talking, I run silently to the tunnel mouth. I know there are several doors on the Central line which will give me access to the Guild passages, and, once I’m in one of those, it will be simple enough to find my way back to Hyde Park. Most importantly, I need to get off the rails before the train comes through.

Inside the total darkness of the tunnel, I dare to turn on my torch again. It doesn’t make a lot of difference – the light was dim when I used it earlier in the museum, and it’s lost power since then and is frustratingly weak, but it’s all I’ve got. I push on. Five minutes of jogging and I find what I’m looking for – a small wooden door set into the side of the service passage leading off from the Central line.

The sounds of trains on the other tracks are closer now, rumbling and rattling, and screeching as they brake. To some people it could be unsettling – frightening even – knowing that these fast engines are racing through the tunnels surrounding them. But I’m used to this – used to walking underground, used to being a little bit too close to forces that might harm me. Taking the Guild key from round my neck, I don’t even pause before putting it into the lock. I’m also growing accustomed to breaking the rules.

Still, after waiting all summer to take the Trial, I can’t help but shudder at the thought of the consequences if I get caught down here. I open the door and step into a narrow tunnel which is far cleaner and better kept than the one I’ve just come from. As I enter, lights come on – automatic sensors picking up my movement. This brightly lit corridor is more disconcerting than the previous one: there’s nowhere to hide.

I turn off the little torch and put it in my pocket. One of my brain’s tricks is an internal compass that I use to navigate. I have a lot of tools like this – internal filing cabinets and visual memory aids – but I can’t explain how most of them work, even to myself. They just do. I walk a little way, passing various doors on my left, until I reach one on my right, which my compass tells me is the right direction for home. I open it and pass through, and walk for fifteen to twenty minutes, checking over my shoulder the whole time. At last, I come to a sign on the wall with arrows pointing in two directions. One of the arrows points towards Piccadilly Circus, the other towards Marble Arch.

Marble Arch is close to home, so I head in that direction. This isn’t the most exciting Guild passage, with very little to see in the way of other routes branching off from it, and it’s not carpeted and wood-lined like some of the more elaborate ones, such as those that run under Hyde Park. However, it’s good to be out of the bright lights of the larger tunnel. It also has a smooth surface, and I begin to jog again, enjoying the rhythmic pace, which lets my brain slow down and start to process the information I’ve gathered so far.

The maze of underground pathways that runs under London was only partly constructed by the Guild, of course. They patched together several networks, from old Roman and Victorian sewers to modern service pipes, plus parts of the Tube, the electricity board’s passageways, the water board’s, sections of underground car parks and even telephone exchanges. This patchwork design can be quite useful, because it often gives you a clue as to where you are. In the tunnels I’ve visited near the South Bank (beside the Thames), the walls are made of an orangey concrete, with two rows of lights down either side. In the tunnels near to Buckingham Palace, they are plush, as though in preparation for a royal visit, and have chandeliers in place of bare light bulbs.

I’ve never been in this part of the network before, so I make sure I commit it to memory in case I’m ever here again and need to find my bearings. It’s weird, heading in the direction of home without any of the familiar landmarks I would have above ground. I’m jogging at a comfortable pace when I hear a faint sound behind me.

I glance over my shoulder.

The tunnel is slightly curved, so I can’t see what’s making the noise. But I listen very carefully. It’s a regular tapping. Perhaps just a leak? No, it doesn’t sound like that: it’s too regular, and that rhythm …

Footsteps.

They’re getting louder. Someone’s running in my direction. I look back again. As they come round the bend, they’re just a shadowy figure. The only thing I can make out is that, when they see me, they speed up.

There’s no time to lose. I pick up my own pace, racing like I’m doing the hundred-metre sprint. If the person behind me is from the Guild (and who else would it be, down here in the Guild tunnels?) then I can’t let them catch me, or they’ll be bound to bar me from taking the Trial. I run and run until my blood is thudding in my ears. My feet are pounding so hard against the concrete that they’re starting to throb. At least I seem to be increasing the distance between us, though. After a little while I come to a branch off to the left. I’m dizzy from the run, and have to pause before my vision clears enough to read the next sign. With a sigh of relief, I see it says HYDE PARK 1⁄3 MILE.

In the brief time I’ve been standing still, the footsteps have become much louder. The person following me is really close now. With one last push, I race down the offshoot. There’s no lighting, but I can make some out ahead, filtering through from the far end of the tunnel. This passage is also straighter than the one I was just in and, after a few moments, I glance back into the darkness and see a torch heading through the darkness towards me.

My forehead is dripping with sweat and my breathing is becoming painful. I keep glancing back, and the light is still there, following a little way behind. Whoever’s chasing me can’t catch up, but they’re not falling back either. Off in the distance I see it at last – a spiral staircase leading up from the tunnel floor.

It takes an almost Herculean effort to make it up the stairs. I have to stop partway up because my calves are aching badly. I bend over, panting and rubbing my legs, convinced my tracker will reach me. Then the area below lights up from their torch, and that’s enough of an incentive to send me climbing again, up and up, above the roof of the tunnel.

Finally, the spiral staircase ends. I see a small iron door in front of me; I put my Guild key into the lock; and, just as my pursuer’s foot sounds on the bottom rung of the metal staircase, I step through the door, out into the cold night air, and shut the door firmly behind me, panting loudly.

The moon is bright and full, showing me that the door is set into a stone embankment, near the Serpentine lake. I’m not far from home and I don’t have time to stand around. After taking a second to get my bearings, I race away across the lawns, into the night.

Usually, when getting home late, I climb back up the oak tree and in through the skylight. But there’s no way my legs will cope with that tonight. Plus, it’s so late that all the lights are off in the cottage. Dad must be in bed. I don’t want to spend any more time outside than I need to, not when somebody might still be tailing me. So I take out my house keys and, as quietly as possible, go in through the front door.

I collapse in the hallway, leaning against the front door and breathing heavily. The excitement of the evening, and the chase through the tunnels, have worn me out. But my mind’s as alert as ever, buzzing with ideas and theories, with images from the museum and the underground station.

I decide to get myself a glass of milk. Maybe that will help me get to sleep. There’s no point in me staying up all night, trying to solve a case where I don’t have all the facts. I will wake up rested tomorrow and start again, with Liam and Brianna to help me.

It’s dark in the kitchen, but I don’t want to turn the light on. The moon’s shining through the window and it’s just about enough to see by. I open the fridge, letting out a refreshing blast of cold air. I take out the milk, close the door, and turn towards the cupboard, where the glasses are kept.

As I do, I jump, so startled that I drop the carton of milk on the floor.

There’s someone standing in the corner of the kitchen, waiting silently in the shadows.

I stumble away, pressing my back to the work surface. Without taking my eyes off the intruder, I feel for a knife in the knife block. But my silent companion doesn’t move. I focus hard on their outline. There’s something not quite right about this person.

Walking over, I flick the light on.

For a few seconds, I’m blinded. But then I can see what startled me – one of Dad’s old suits. It’s hanging on a coat hanger from a hook on the wall, a double-breasted jacket over the trousers below. This is a particularly offensive article from Dad’s wardrobe: double-breasted brown twill with mustard pinstripes. Someone should have been arrested for creating this suit. And someone should definitely arrest Dad for wearing it. Knowing him, he’ll probably team it with a mustard shirt and his favourite green tie. I love him dearly, but his fashion sense could do with some help.

Dad said he had to visit another gardener in the morning, but why would he be putting on a suit to visit an orchid specialist? Especially a suit he hasn’t worn in years – a suit which, though it’s hard to believe, he thinks is very flattering. I walk up to the offending outfit and tentatively sniff it, and the smell it gives off confirms my suspicion – this suit has recently been dry-cleaned. It looks smart: pressed and lint-rolled of even the slightest speck of dust. Who is Dad trying to impress?

I pour myself a glass of milk, replace the carton in the fridge, turn out the light, and begin my weary climb to bed. I navigate my way upstairs, avoiding the creaky steps. I’m conscious that I’m still wearing my disguise and am now streaked with grime from the dirty tunnels through which I’ve been running and crawling. If Dad were to see me now, like this, his suspicions would certainly be raised.

Dad knows I love investigating, but I think he imagines that I’m out looking for people’s lost cats, or watching for shoplifters at the corner store. Not that there’s anything wrong with either of those, but I have bigger fish to fry. Dad doesn’t know about these bigger fish: about the Guild, or about the work they do, protecting the capital from the plots of dangerous, greedy people.

Which is for the best really.

I can hear Dad snoring loudly as I climb the stairs. At the top, a sudden ‘Meow!’ makes me freeze. Oliver has come to welcome me. He purrs loudly and pushes his stocky body against my legs.

‘Shhh, Oliver!’ I scoop him up with the arm that isn’t carrying the milk and let him drape himself round my neck. It’s far too warm for this, but I love feeling his vibrating purr. I wait for a moment, to make sure Dad’s still snoring, then creep up the flight of wooden steps to my attic bedroom.

I set Oliver down gently on the floor and look around me. Everything is laid out as I left it, but it seems like I’ve been gone for so much longer than a few hours – as though I left yesterday, or a week ago.

Adventure is a bit like that – you feel as though you’ve been moving very fast, and the rest of the world has been moving very slowly, and you can’t quite believe that it’s still Wednesday, or whatever day of the week it is, because it seems like you’ve lived a week – a month, a year! – in a short space of time. I suppose I like this feeling a bit too much – I rely on the adrenaline rush to keep my life from getting dull – but I try not to worry about that.

I go over to sit on my bed and sip at the glass of milk. I wonder if Mum ever felt like this, when she was a Gatekeeper. You don’t get into this line of work if you don’t like excitement – if you don’t thrive on risk. Did she worry that one day her escapades would get her into serious danger? Or did she live her life from day to day, not worrying about what tomorrow would bring? I look over at her photo on my bedside table.

Looking at this picture usually makes me feel sad or wistful, similar perhaps to what I’d feel if I was looking at a picture of a house that I used to live in – a happy memory. But, tonight, I don’t feel sad or wistful.

I feel angry.

I decide to analyse this new response. I run through what I know – and don’t know – surrounding her death:

1. Whatever happened to Mum, it wasn’t a bike accident.

2. I have a hunch that her death was linked to her work as a Gatekeeper.

3. Someone’s covered up what actually happened – could it have been the Guild?

I realise my new anger is because I’ve just had a close encounter with someone who almost certainly belonged to the organisation. I feel something close to rage at whoever caused Mum’s death – but also at whoever hid the truth from Dad and me. I close my eyes and focus on my breathing until I’ve calmed down enough to turn the rage into determination.

‘I will find out what happened to you, Mum,’ I promise her photo.

Finally, with no energy left to think or feel, I get under the covers, drink the last of my milk (thinking how Mum would have scolded me for not brushing my teeth) and turn the light out. Just before I drift off, I remember the swab that will need analysing. I grab my mobile, switch it on, and send Brianna a text, asking if I can go over to hers the next morning. Then I let sleep pull me under its thick surface.

(#ulink_067d41d0-dc31-5a28-bab0-433a3be6b218)

I wake up late and check my mobile. Brianna replied at about 2am.

Sure. Come over whenever

I don’t know what she was doing up in the early hours, but I guess I’ll find out when I see her.

I pull on my dressing gown and head down to the kitchen. Dad and the brown twill suit have both gone. He’s left me a note:

Gone to that meeting I mentioned.

May be back late.

Help yourself to croissants.

Croissants are my favourite. I’m just cynical enough to suspect he’s done something wrong – or is planning to do it – if he’s buying me my favourite breakfast food. This doesn’t stop me accepting it, though. I eat a croissant, down a glass of orange juice, then go up for a shower before getting dressed. I choose one of my mum’s floral shirt dresses over a pair of jeans. I add a wide black belt to cinch in the dress, and top off the ensemble with a denim jacket. I love wearing Mum’s things – it makes me feel closer to her. I toughen up the look with my Doc Martens boots.

I stuff a couple of croissants in my jacket pockets and munch on another as I head across Hyde Park towards Cadogan Place. It’s quicker to walk to Brianna’s than take public transport. It’s close to noon, and the air is muggy for early September, but the light is glorious, gilding the trees.

I turn into Sloane Street, the home of super-expensive designer shops like Louis Vuitton and Chanel. Brightly coloured flags fly outside the embassies for Denmark, Peru and the Faroes. A black cab driver has got out of his vehicle next to the Danish embassy. He’s on his knees, unwinding what looks like a long piece of black plastic bin liner from one of his back wheels. I recognise him as one of the drivers from the taxi rank outside the park.

‘Hi, Aleksy!’ I call.

‘Hi, Agatha. Just look at this mess. I wish people weren’t so careless with their rubbish,’ he says. ‘This could affect my brakes if I don’t get it all out.’

‘Is there anything I can do to help?’

‘No, that’s all right, thanks. No point both of us getting filthy.’

‘OK, if you’re sure. Good luck!’

‘Thanks!’

I leave him and continue my walk. I demolish the last croissant at the corner of Brianna’s road, and dust the pastry flakes off my hands.

When I reach the grand townhouse on Cadogan Place, Brianna throws open the door. She couldn’t look less like a CC these days: there’s not a trace of the over-manicured mannequin that Liam and I loved to hate, before we got to know her. The CCs are the Chic Clique, a group of annoying, wealthy, smug girls, all with identical long blonde hair, thick make-up and manicured nails, that go to my school. Brianna’s hair – which has been dyed a brilliant sky blue, cut to chin length and then shaved on one side – is sticking up messily at the back, and her black eyeliner is smudged, giving her panda eyes. She looks like she hasn’t slept in weeks.

‘Fantastic shade of blue!’ I say, ruffling her already ruffled hair, and she grins and gives me a hug.

‘Thanks! Thought it made a change from last week’s pink.’ She pulls back to look at me. ‘I love the dress. Another one of your mum’s?’

I nod, happily, and follow her as she leads the way to the study, where she seems to spend most of her time.

‘Have you slept at all?’ I ask as I follow her through the massive, marble-paved hallway. ‘You look shattered.’

She shakes her head. ‘I’m doing research into how long a person can survive on no sleep.’

‘Really? How long have you managed so far?’

She squints blearily at her watch. ‘Ummm … something like thirty hours?’ She sounds unsure.

‘Isn’t sleep deprivation one of the ways they torture people?’

She grins ‘Yeah. But it’s a bit different when you’re safely at home.’

I’m confused. ‘So how does this fit with you wanting to be a forensic scientist?’

She shrugs. ‘I want to get inside the heads of criminals, so I’m trying out a few torture methods on myself.’ She sees the look of alarm on my face and quickly adds, ‘Just the easy, painless ones – a dripping tap, sleep deprivation, that kind of thing.’

‘Your mum and dad are away again?’ I ask.

‘Do you need to ask?’

Her parents (or ‘seniors’, as she calls them) are always travelling to glamorous locations, leaving Brianna in the care of her rather careless and frequently absent older brother.

‘Missed you at the cinema,’ I say. ‘It was a good one.’

‘Yeah – Liam said. But I had way too much to do.’ She leads me through to the study, where I stop in surprise at the sight of Liam. He’s sitting in a chair at the desk, leaning back with his feet up. His face breaks into a beam when I enter, and he gets up and hurries over.

‘Hey – great to see you.’

‘So, this is why I’m here …’ I begin.

‘You mean it’s not just for the pleasure of my company?’ says Brianna, pouting.

‘Stop doing that with your face,’ I tease her. ‘You remind me of when you were in the CCs – all fake pouts and baby voices.’

She shudders. ‘Don’t. I can’t bear to remember it. Was I awful?’

‘Awfully awful,’ I tell her gravely. ‘You’re lucky you’ve got me and Liam now to keep you grounded.’

‘Did you hear about the horrible thing Sarah’s done to me?’ she asks. She means Sarah Rathbone – queen of the CCs and her ex-best friend, of course.

‘No, what’s happened this time?’

‘She’s posted awful pics of me again, all over Instagram. She’s Photoshopped them, so I look like I’ve got really bad acne.’ She hands me her phone, and Liam and I study the pictures. Brianna looks quite different when she’s covered in pimples.

After a moment, Liam nods approvingly. ‘That’s pretty skilled work. It must’ve taken ages to make the spots look authentic.’ Brianna doesn’t seem offended.

‘Oh – she had help. She’s got a cousin who’s really good at editing photos.’

I hand back the phone. ‘So why is she doing it this time?’

Brianna is trying to look nonchalant, but I can see it’s hurt her. ‘Just part of her ongoing campaign to humiliate me.’ She shrugs. ‘For deserting the posse.’

‘Nice,’ I say, pulling a face.

‘At least it confirms I made the right move, leaving the CCs,’ she says.

‘I heard they were holding auditions for your replacement,’ says Liam. ‘Wasn’t there some girl who bleached her hair because she was so desperate to get in?’

‘Yeah, Cherry-Belle McLaughlin – you know, the footballer’s daughter.’

‘The one with all that long black hair?’

Brianna pulls a face. ‘Not any more. Now it’s bright orange and she’s having treatment to try and stop it breaking from the bleach damage.’

‘Ouch!’ I say, and Liam nods in agreement. There’s a word, Schadenfreude, which basically means taking pleasure in other people’s pain or misery. As the year’s ‘misfits’, ‘geeks’ or whatever you want to call us (I prefer ‘mavericks’), we’ve been on the receiving end of far too much Schadenfreude to relish other people’s misfortune.

‘So,’ says Liam, pointedly changing the subject, ‘how did you get on at the museum?’

‘OK.’ I pat my pockets. ‘I’ve got a swab sample I’m hoping Brianna will analyse for me.’ I produce the vial containing the cotton bud.

‘Where did you take it?’

After I fill them in about what happened at the British Museum, Liam makes a low whistling sound of admiration. I feel myself blush.

‘So you really did manage to get in then?’

‘Yeah.’

‘That’s our girl,’ says Brianna. She yawns and stretches. ‘Not sure how much longer I can stay awake, by the way,’ she says apologetically. She checks her watch and makes a note in an open exercise book. ‘Thirty-one and a half hours,’ she murmurs.

‘Did you use the Gatekeepers’ key to get in?’ Liam asks me. I frown a warning at him: we’re not supposed to talk about the Guild in front of Brianna. ‘You know you’re going to get murdered if the professor finds out.’

But Brianna doesn’t seem to be listening. She’s walked over to a light switch near the bookcases on the back wall of the study. She flicks the switch casing open and presses a keypad. A section of the bookcase swings back. I never tire of seeing this: it’s such a classic secret-room device. If I ever envy Brianna, it’s not for her huge house, nor for the library (and I do mean an actual library, in its own room, with a high-up reading area like a balcony) – but for her secret room filled with all the paraphernalia a detective could ever dream of. She’s collected so many gadgets and chemical testing kits in her private lab over the years, as long as she’s been dreaming of becoming a forensic scientist. I feel pretty lucky to have got to know her – not just for her gadgets but for our shared love of all things investigative.

But while we’ve been distracted by the bookcase, Brianna has slumped against the wall, her eyes closed. ‘Sorry, but I need to sleep now,’ she murmurs. ‘Can we do this later?’

‘Of course,’ I say. I drag one of the curve-back study chairs over to her side and Liam helps me manoeuvre her into it. He finds a blanket in another room and drapes it over her.

Once we’re satisfied she’s comfortable, we walk inside the secret lab. Liam hasn’t been in here before and he stops on the threshold, taking in the extraordinary sight. It’s just how I have remembered it. Metal shelving fills the walls, and there are all sorts of tools and equipment on every shelf, including test tubes, pipettes, Petri dishes and bell jars. I walk past Liam, running my hand along a row of bottles containing various substances arranged in alphabetical order from acetic acid to zinc. I take mental pictures of all the supplies – just in case I ever need something.

In the centre of the room there’s a stainless-steel table furnished with a Bunsen burner. I’m itching to set the flame alight, but I hold back. It’s not mine, and I should really wait for another day when I can ask Brianna whether I can come and try out some experiments.

‘This place is amazing!’ says Liam.

‘I know. I wish I had one.’

‘Hey – at least she’s willing to share it.’

‘True.’

We’re silent for a moment, studying the room. Then Liam says quietly – not for the first time, ‘Brianna’s not at all what I expected.’

‘I know. She’s not all about her Instagram image at all.’

Reluctantly, I take a final look around the room of sleuthing treasures. ‘OK – better close this up, I guess – I don’t feel like I should use the equipment to test the swab without her.’

We come back out and close the bookcase, and I place the vial on the mantelpiece, with a page torn from my notebook propped up behind it, bearing the words Please test me!

‘OK,’ says Liam, ‘shall I walk you to the Tube?’

I laugh. ‘It’s broad daylight, in a built-up area – I’m pretty sure I don’t need an escort. But we can walk together if you like.’

We head out of Brianna’s house, making sure the front door latches properly behind us. The street is quiet as we walk towards the Underground station, and the air has become even more muggy, as if Liam has draped a blanket over not just Brianna, but the whole of London too. When we get to the Tube, he gives me a quick wave.

‘See you tomorrow,’ he says.

My heart sinks. School! How will I ever do the Trial when I’m stuck in a classroom all day?

I watch him walk off to his bus stop. I know his walk so well, I could pick him out in any crowd: swift and eager, as if there’s always something good round the next corner.

I don’t go home. I’m due at my martial arts lesson with Mr Zhang. I’m not sure why I haven’t told Liam about these lessons. After all, he knows pretty much everything about my life. If I’m honest with myself, it’s probably just that I want to be much more proficient before I share it with him. At the moment, I’m little more than a beginner. Vanity affects us all to some degree, I guess.

This is a new pursuit for me, which was suggested by Professor D’Oliveira. Actually, ‘suggested’ is too gentle a verb. Her exact words were: ‘If you’re going to be running about London like a headstrong fool, you’ll need some decent skills.’ I’d bridled at that. I had plenty of skills, many of which she still knew nothing about.

Still, she’d given me Mr Zhang’s card and said to tell him Dorothy had sent me.

The martial arts gym (called a dojo) is beneath Mr Zhang’s restaurant – the Black Bamboo – in the Soho area of central London, which he runs with the help of his granddaughter, Bai.

I open the wooden door and step inside. Bai is sitting on a stool at the bar, surrounded by textbooks. She fits working at the restaurant around her law studies. Bai stands politely to greet me. She is tall and slender – she always reminds me of a silver birch tree; her hair is long, and today she’s wearing it knotted at the nape of her neck. She’s dressed in a silky sheath dress with an all-over print of poppies.

‘Hi, Bai. You look lovely.’

She smiles. ‘Hi, Agatha. Thank you. I love your dress! You can change into your gi in the back room.’

Bai gestures for me to go through a curtain made from vertical strips of coloured plastic. It leads to a tiny room at the back, where I quickly remove my dress and jeans and don my white gi, which I’ve brought in my backpack. I fold my clothes and place them on a chair, with my boots underneath. I stop for a second to study a symbol framed on the wall above the chair.

I know it’s the symbol for biang biang noodles. Mr Zhang has explained that it is one of the hardest symbols to write in the Chinese language. The story goes that the symbol was invented by a poor scholar who didn’t have any money to pay for his bowl of biang, so he offered the cook a symbol to advertise his dish. It’s so complicated that there’s still no way to type it on computers or phones. Luckily, there’s a mnemonic for writing it by hand. Mr Zhang taught it to me:

Roof rising up to the sky,

Over two bends by Yellow River’s side.

Character eight’s opening wide,

Speech enters inside.

You twist, I twist too,

You grow, I grow with you,

Inside, a horse king will rule.

Heart down below,

Moon by the side,

Leave a hook for fried dough to hang low,

On our carriage to Xianyang we’ll ride.

I leave the room and descend a set of red-tiled stairs to the basement. Back underground, where I belong, I think to myself, with a wry smile. I seem to be spending all my life in basements and tunnels at the moment.

Mr Zhang is waiting for me when I open the door. He is dressed in a black suit – his gi – and his grey hair is scraped back from his face and fixed in place with what look like chopsticks. Mr Zhang frequently loses personal items such as his glasses, his house keys, or the special sticks he uses to hold his hair in place. One time when I came, he was hunting for a pen, and I had to point out that he had two in his hair. For a true master of his trade, Mr Zhang can be surprisingly flaky.

We bow to one another and I approach him, barefoot, across the wooden floor. I would love to say that Mr Zhang lunges at me and I defend myself with a skilful move, throwing him halfway across the room – but my lessons aren’t like that. Instead, he instructs me to work through the ‘forms’ he’s taught me so far – the sequences of movements which will, eventually, lead to more complex skills.

When I finish, there is a long silence.

‘You have been practising these forms?’

‘Yes.’ I have been doing them every morning and evening throughout the holidays. I only forgot last night and this morning, with all the excitement of the new case.

‘Hmmm.’

I stand and wait for his judgement.

At last, he clears his throat and says, ‘We will take some tea.’

He leads me to a little table, at which we each take a seat, and he pours jasmine tea from a decorative pot into small matching cups without handles, like tiny bowls. All of the china at the Black Bamboo features the same pattern: a delicate, sketch-like outline of bamboo canes and leaves on a white background. I love the way the tiny cup feels in my hand – smooth, warm and fragile, like a soon-to-hatch egg.

We don’t talk for a while. I’m trying to learn patience, but it defeats me eventually. ‘Was I that bad?’ I ask my sifu (my ‘master teacher’).

‘Bad? What?’

‘My forms … were they so bad?’

He nods. ‘Ah, the forms.’ He leans his head to one side in a pensive pose. Then he pats my hand gently. ‘Do you know the expression “The one who waits wins”?’ Mr Zhang has countless similar expressions, each of which he presents as if it’s a wise adage, handed down through hundreds of generations. Between you and me, I suspect he invents them himself.

I shake my head.

‘Ah. You must learn the art of patience, dear Agatha. Only then will you achieve true balance and expertise.’

I wait, but no further wisdom comes. Instead he says, ‘Chocolate biscuit?’ and holds out a plate of Penguins. ‘I like the jokes,’ he confides.

We finish our tea and biscuits and then I do some training with a broadsword. This is my favourite part. Not all beginners get to practise with serious weapons like the broadsword – but apparently Professor D’Oliveira insisted I be fast-tracked to gain competence in the wielding and safe use of basic weapons.

‘Good, good,’ he says, his head on one side. ‘Now adjust your stance, just so …’

After my class, I head back up the stairs to the antechamber where my clothes are waiting. But something is different: on top of my folded floral dress is a tiny white parcel. I pick it up.

As I look more closely, I realise that it’s not a parcel but a flower; a perfectly folded piece of paper in the shape of a bud. But what is this unlikely bloom doing here, on my clothes? Did Bai put it here? It’s so complex that I can’t imagine how each fold was created to achieve this elaborate design. As I peer closely, I think I can make out some writing inside – but I don’t want to risk damaging the paper by attempting to open it along the wrong folds.

I decide to ask Bai about it. Cradling the paper creation gently in my palm, I walk through the strip curtain to the restaurant. Bai is perched on a bar stool, making notes from a textbook. She looks up as I approach.

‘What have you got there?’ Her face brightens as she sees the origami. ‘Oh! It’s lovely!’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/lena-jones/murder-at-the-museum/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Lena Jones

A second mystery for thirteen-year-old Agatha Oddly – a bold, determined heroine, and the star of this stylish new detective series.Agatha Oddlow’s set to become the youngest member of the Gatekeepers’ Guild, but before that, she’s got a mystery to solve!There’s been a murder at the British Museum and, although the police are investigating, Agatha suspects that they’re missing a wider plot going on below London – a plot involving a disused Tube station, a huge fireworks display, and five thousand tonnes of gold bullion…

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2019

Published in this ebook edition in 2019

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Children’s Books website address is

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Text copyright © Tibor Jones 2019

Cover design copyright © HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Cover illustration by Alba Filella

Tibor Jones asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008211899

Ebook Edition © March 2019 ISBN: 9780008211905

Version: 2018-12-12

For Lizzie and Hannah

Contents

Cover (#u12fc5da0-cbd7-53ff-9b6f-d0090600fcfa)

Title Page (#u91fa9922-727c-5658-8d70-5bf4361e9c41)

Copyright (#ubb6356e4-8175-58d7-8df4-ea519ea8897a)

Dedication (#ued77156c-d6b7-5781-a633-4dacad017dd7)

1. Rule Breaker (#u6e024477-c1e6-51e5-a130-00ef4c562178)

2. Work Placement (#u57bfad6a-d1d6-5397-a014-1f79b1089d8b)

3. Crawl Space (#u1eb2c88e-7180-5a56-835d-1a851847b50d)

4. The Black Bamboo (#u53e2ff4f-01d4-575c-a09e-ceabe7eb228f)

5. The Sinkhole (#litres_trial_promo)

6. The Forgotten Underground (#litres_trial_promo)

7. New Girl (#litres_trial_promo)

8. Homework (#litres_trial_promo)

9. Smugglers’ Dock (#litres_trial_promo)

10. Found Out (#litres_trial_promo)

11. Running out of Time (#litres_trial_promo)

12. Land of Gold (#litres_trial_promo)

13. A Cold Dip (#litres_trial_promo)

14. A Sweatshirt in the Works (#litres_trial_promo)

15. Rescued! (#litres_trial_promo)

16. Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Onomatopoeic Cipher (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

Read all the Agatha Oddly adventures (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

(#ulink_2262b26c-6745-5480-b8e7-fd08a85f0883)

‘That film was crazy!’ says Liam with satisfaction as we step out of the Odeon.

The evening air is pleasantly warm and there are still hordes of people milling around in Leicester Square. We navigate through them. Liam turns his phone back on, while I fish out the last scraps of popcorn from my box. We’ve just seen the latest crime thriller – Midnight Delivery – and can’t wait to point out all its plot holes.

‘I knew it was the window cleaner,’ I say. ‘He was far too nosy. And as for the detective – he was soooo slow.’ I laugh. ‘Brianna would’ve had a field day! Why did she say she couldn’t come?’ Liam is my best friend, but Brianna is a close second. The three of us hang out together a lot.

‘Oh … I think she had homework,’ he says.