Interviews From The Short Century

Interviews From The Short Century

Marco Lupis

Marco Lupis

ISBN: 9788873043607

This ebook was created with StreetLib Write

http://write.streetlib.com (http://write.streetlib.com)

Table of contents

About the author (#u98e8a4ea-5a9c-57f8-8c6b-e2edf00c99d9)

INTERVIEWS FROM THE SHORT CENTURY (#u9fe1cb2b-9e35-5711-a294-e1ed58ca26e6)

LITERARY PROPERTY RESERVED (#u93a9a4d8-690d-53b4-bc01-28a5cc76cce7)

Introduction (#u22cb285b-0dcf-5895-af8d-823d14c657c5)

Subcomandante Marcos (#ucb5797c0-a8d1-5121-9f3a-34f0194f241a)

Peter Gabriel (#u05db8b34-6ae5-5e4b-a77b-43ea4e98e25d)

Claudia Schiffer (#u2a674c71-b8e3-5897-9f3e-bb5fa9aa18b0)

Gong Li (#uc39525d9-a34f-5c2d-af53-4294f84c118d)

Ãngrid Betancourt (#u4c2588f8-a01d-5adf-9bb4-53ce9b3d0327)

Aung San Suu Kyi (#u317b25a3-def5-5f22-bcce-868a7ca9e050)

LucÃa Pinochet (#u9639dc5a-e8e4-5ed7-b08f-198ce1be77c6)

Mireya GarcÃa (#u8d6b6d26-d979-51e3-9101-fdc2d1d9eccb)

KenzaburÅ Åe (#litres_trial_promo)

Benazir Bhutto (#litres_trial_promo)

King Constantine II of Greece (#litres_trial_promo)

Hun Sen (#litres_trial_promo)

Roh Moo-hyun (#litres_trial_promo)

Hubert de Givenchy (#litres_trial_promo)

Maria Dolors Miró (#litres_trial_promo)

Tamara Nijinsky (#litres_trial_promo)

Franco Battiato (#litres_trial_promo)

Ivano Fossati (#litres_trial_promo)

Tinto Brass (#litres_trial_promo)

Peter Greenaway (#litres_trial_promo)

Suso Cecchi dâAmico (#litres_trial_promo)

Rocco Forte (#litres_trial_promo)

Nicolas Hayek (#litres_trial_promo)

Roger Peyrefitte (#litres_trial_promo)

José Luis de Vilallonga (#litres_trial_promo)

Teresa Cordopatri (#litres_trial_promo)

Andrea Muccioli (#litres_trial_promo)

Xanana Gusmão (#litres_trial_promo)

José Ramos-Horta (#litres_trial_promo)

Basilio do Nascimento (#litres_trial_promo)

Khalida Messaoudi (#litres_trial_promo)

Leonora Jakupi (#litres_trial_promo)

Lee Kuan Yew (#litres_trial_promo)

Khushwant Singh (#litres_trial_promo)

Shobhaa De (#litres_trial_promo)

Joan Chen (#litres_trial_promo)

Carlos Saúl Menem (#litres_trial_promo)

Pauline Hanson (#litres_trial_promo)

Dmitri Volkogonov (#litres_trial_promo)

Gao Xingjian (#litres_trial_promo)

Wang Dan (#litres_trial_promo)

Zhang Liang (#litres_trial_promo)

Stanley Ho (#litres_trial_promo)

Palden Gyatso (#litres_trial_promo)

Gloria Macapagal Arroyo (#litres_trial_promo)

Cardinal (Jaime) Sin (#litres_trial_promo)

Võ Nguyên Giáp (#litres_trial_promo)

Sergio Corsini (#litres_trial_promo)

Macram Max Gassis (#litres_trial_promo)

Men Songzhen (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

About the author

By the same author:

Il Male inutile

I Cannibali di Mao

Cristo si è fermato a Shingo

Acteal

On board a US Army helicopter, mid-mission

Marco Lupis is a journalist, photojournalist and author who has worked as La Repubblica âs Hong Kong correspondent.

Born in Rome in 1960, he has worked as a special and foreign correspondent the world over, but mainly in Latin America and the Far East, for major Italian publications ( Panorama , Il Tempo , Corriere della Sera , LâEspresso and La Repubblica ) and the state-owned broadcaster RAI. Often posted to war zones, Marco was one of the few journalists to cover the massacres in the wake of the declaration of Timor-Lesteâs independence, the bloody battles between Christians and Muslims in the Maluku Islands, the Bali bombings and the SARS epidemic in China. He covered the entire Asia-Pacific region, stretching from Hawaii to the Antarctic, for over a decade. Marco has interviewed many of the worldâs most prominent politicians, particularly from Asia, including the Burmese Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi and Pakistani prime minister Benazir Bhutto. His articles, which often decry human rights abuses, have also appeared in daily newspapers in Spain, Argentina and the United States .

Marco Lupis lives in Calabria.

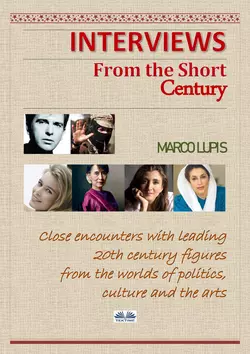

INTERVIEWS FROM THE SHORT CENTURY

INTERVIEWS

from the Short Century

Marco Lupis

Close encounters with leading 20th century figures from the worlds of politics,

culture and the arts

Translated by Andrew Fanko

Tektime

LITERARY PROPERTY RESERVED

Copyright © 2017 by Marco Lupis Macedonio Palermo di Santa Margherita

All rights reserved to the author

interviste@lupis.it

www.marcolupis.com (http://www.marcolupis.com)

First Italian edition 2017

© Tektime 2018

ISBN: 9788873043607

This work is protected by copyright.

Any unauthorised duplication, even of part of this work, is strictly forbidden.

The journalist is the historian of the moment

Albert Camus

For Francesco, Alessandro and Caterina

Introduction

Tertium non datur

As I walked briskly along Corso Venezia towards the San Babila theatre on an autumnal day in Milan back in October 1976, I was about to conduct my very first interview.

I was sixteen years old, and together with my friend Alberto I was hosting a radio show for young people called âSpazio giovaniâ on one of Italy's earliest privately owned stations, Radio Milano Libera .

These were incredible times, when it seemed as though anything could happen, and frequently it did. Marvellous times. Horrible times. These were the anni di piombo [the Years of Lead], the years of youth protest, anarchy, strikes in schools and demonstrations that inevitably ended in violence. These were years of hope, filled with a cultural fervour so vibrant and all-consuming that it drew you in and threatened to explode. These were years of young people fighting and being killed, sometimes on the left and sometimes on the right. These were simpler times: you were either on one side or the other. Tertium non datur.

But above all, these were times when every one of us felt, and often knew, we had the power to change things. To â in our own small way â make a difference .

Amid all the chaos, excitement and violence, we were actually pretty laid back, taking things as they came. Terror attacks, bombings, the Red Brigades...these were all part and parcel of our youth and adolescence, but overall they didn't worry us excessively. We had quickly learned to survive in a manner not too dissimilar to that which I would later encounter among those living amid conflict or civil war. They had adapted to such extreme living conditions, a bit like we had back in the 1970s.

Alberto and I really wanted to make a difference. Whereas today's kids are engrossed in selfies, Instagram and smartphones, we poured our boundless enthusiasm and utterly carefree attitude into reading everything in sight and going to concerts, music festivals (it was that magical time when rock music was really taking off) and film clubs.

And so it was, armed with a dictaphone and our heads full of dreams, we made our way hurriedly towards the San Babila theatre on that sunny October afternoon more than forty years ago.

Our appointment was at 4pm, an hour before the matinée performance was due to begin. We were led down to the basement of the theatre, where the actors had their dressing rooms, and waiting for us in one of them was the star of the show and my first interviewee: Peppino De Filippo.

I don't remember much about the interview, and unfortunately the recordings of our radio show must have got lost during one of my many moves.

What I can still remember clear as day is the buzz, that frisson of nervous energy that I felt â and would feel plenty more times in my life â before the interview began. I say interview, but really I see an interview as a meeting ; it's a lot more than just a series of questions and answers.

Peppino De Filippo was coming to the end â he died just a few years later â of what was already a legendary career acting on stage and screen. He greeted us without getting up from his seat in front of the mirror, where he was doing his make-up. He was kind, courteous and engaging, and he pretended not to be taken aback when he found himself confronted with a couple of spotty teenagers. I remember the calm, methodical way in which he laid out his stage make-up, which looked heavy, thick and very bright. But the one thing that really sticks in my mind is the profound look of sadness in his eyes. It hit me hard because I felt his sadness so intensely. Perhaps he knew that his life was drawing to a close, or maybe it was proof of the old theory about comedians: they might make everybody else laugh, but they are themselves the saddest people in the world.

We spoke about the theatre and about his brother Eduardo, naturally. He told us how he had born into show business, always travelling around with the family company.

When we left after nearly an hour in his company, we had a full tape and felt a little fuzzy-headed.

That wasn't just my first interview; it was the moment I realised that being a journalist was the only career choice for me. It was the moment I felt for the first time that strange, almost magical chemistry between and interviewer and their subject.

An interview can be a formula to get to the truth, or it can be a futile exercise in vanity. An interview is also a potent weapon, because the journalist can decide whether to work on behalf of the interviewee or the reader.

In my opinion, there is so much more to an interview. Itâs all about psychoanalysis, a battle of minds between the interviewer and the interviewee.

In one of the interviews you will read in this book, José Luis de Vilallonga puts it very nicely: âIt's all about finding that sweet spot where the interviewer stops being a journalist and instead becomes a friend, someone you can really open up to. Things you wouldn't normally dream of telling a journalist.â

An interview is the practical application of the Socratic art of maieutics: the journalistâs ability to extract honesty from their subject, get them to lower their guard, surprise them with a particular line of questioning that removes any filters from their answers.

The magic doesn't always happen; but when it does, you can be sure that the interview will be a success and not just a sterile question-and-answer session or an exercise in vanity for a journalist motivated solely by a possible scoop.

In over thirty years as a journalist, I have interviewed celebrities, heads of state, prime ministers, religious leaders and politicians, but I have to admit that they're not the ones towards whom I have felt genuine empathy.

Because of my cultural and family background, I ought to have felt on their side, on the side of those men and women who were in power, who had the power to decide the fate of millions of people and often whether they would live or die. Sometimes the destiny of entire populations lay in their hands.

But it never happened like that. I only felt true empathy, that closeness and that frisson of nervous energy when I interviewed the rebels, the fighters, those who proved they were willing to put their (often peaceful and comfortable) lives on the line to defend their ideals.

Whether they were a revolutionary leader in a balaclava, hiding out in a shack in the middle of the Mexican jungle, or a brave Chilean mother waging a stubborn but dignified fight to learn the horrible truth about what happened to her sons, who disappeared during the time of General Pinochet.

It seems to me as though these are the people with the real power.

Grotteria, August 2017

*****

The interviews I have collated for this book appeared between 1993 and 2006 in the publications I have worked for over the years as a reporter or correspondent, primarily in Latin America and the Far East: the weekly magazines Panorama and LâEspresso , the dailies Il Tempo , Corriere della Sera and La Repubblica , and some for the broadcaster RAI.

I have deliberately left them as they were originally written, sometimes in the traditional question/answer format and sometimes in a more journalistic style.

I have written introductions to each interview to help set the scene.

1

Subcomandante Marcos

We shall overcome! (Eventually)

Hotel Flamboyant, San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico. A message has been slipped under my door:

You must leave for The Jungle today.

Be at reception at 19:00.

Bring climbing boots, a blanket,

a rucksack and some tinned food.

I have just an hour and a half to get these few things together. Iâm headed for the heart of the Lacandon Jungle, which lies on the border of Mexico and Guatemala and is one of the least explored areas on Earth. In the present climate, no ordinary tour operator would be willing to take me there; the only man who can is Subcomandante Marcos, and the Lacandon Jungle is his last refuge.

*****

That meeting with Subcomandante Marcos on behalf of Corriere della Sera âs weekly magazine, Sette , remains to this day the proudest moment of my career. Even if I wasnât the first Italian journalist to interview him (I canât be certain that the likeable and ubiquitous Gianni Minà didnât get there first, if Iâm honest), it was definitely long before the fabled insurgent with his trademark black balaclava spent the next few years ferrying the worldâs media to and from his jungle hideaway, which he used as a kind of wartime press office.

It had been nearly two weeks since my plane from Mexico City had touched down at the small military airport in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, the capital of the state of Chiapas, at the end of March. Aeroplanes bearing Mexican Army insignia were taxiing on the runway, and various military vehicles were parked menacingly all around. Chiapas was approximately a third of the size of Italy and home to over three million people, most of whom had Mexican Indian blood: some two hundred and fifty thousand were descended directly from the Maya.

I found myself in one of the poorest areas on Earth, where ninety per cent of the indigenous population had no access to drinking water and sixty-three per cent were illiterate.

It didnât take me long to work out the lie of the land: there were a few, very rich, white landowners and a whole load of peasant farmers who earned, on average, seven pesos (less than ten US dollars) a day.

These impoverished people had begun to hope of salvation on 1 January 1994. As Mexico entered into the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with the United States and Canada, a masked revolutionary was declaring war on his own country. On horseback and armed (albeit mostly with fake wooden guns), some two thousand men from the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) were occupying San Cristóbal de las Casas, the old capital of Chiapas. â Tierra y libertad! â [âLand and freedom!â] was their rallying cry.

We now know how that decisive first battle ended: the fifty thousand troops sent in with armoured cars to crush the revolt were victorious. But what about Marcos? What became of the man who had evoked memories of Emiliano Zapata, the legendary hero of the Mexican Revolution that began in 1910?

*****

Itâs seven oâclock at the reception of Hotel Flamboyant. Our contact, Antonio, arrives bang on time. He is a Mexican journalist who tells me he has been to the Lacandon Jungle not once, but dozens of times. Of course, the situation now is very different to how it was a year ago, when Marcos and his comrades enjoyed a relatively quiet existence in the village of Guadalupe Tepeyac, at the entrance to the jungle, equipped with phones, computers and the internet, ready to receive American television reporters. Life for the Mexican Indians has remained constant, but for Marcos and his fellow revolutionaries everything has changed: in the wake of the latest offensive by government troops, the leaders of the EZLN have been forced to hide in the mountains, where there are no phones, no electricity, no roadsâ¦nothing.

The colectivo (a strange cross between a taxi and a minibus) hurtles between a series of hairpin turns in the dark. The inside of the vehicle reeks of sweat and my clothes cling to my skin. It takes two hours to reach Ocosingo, a town on the edge of the Jungle. The streets are bustling and filled with the laughter of girls with long, dark hair and Mexican Indian features. There are soldiers everywhere. The rooms in the town's only hotel have no windows, only a grille in the door. It feels like being in prison. A news item crackles over the radio: âA man has revealed today that his son Rafael Sebastián Guillén Vicente, a thirty-eight-year-old university professor from Tampico, is Subcomandante Marcosâ.

A new guide joins us the next morning. His name is Porfirio and heâs also a Mexican Indian.

It takes us nearly seven dust- and pothole-filled hours in his jeep to reach Lacandón, a village where the dirt track ends and the jungle proper begins. Itâs not raining, but we're still knee-deep in mud. We sleep in some huts we encounter along our route, and it takes us two exhausting days of brisk walking through the inhospitable jungle before we finally arrive, completely stifled by the humidity, at Giardin. Itâs a village in the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve that is home to about two hundred people, all of whom are either women, children or old. The men have gone to war. We are made to feel welcome, but few people understand Spanish. Everybody here speaks the Mayan language Tzeltal. âWill we be meeting Marcos?â we ask. âMaybe,â Porfirio nods.

We are woken gently at three in the morning and told that we need to leave. Guided by the light of the stars rather than the moon, we walk for half an hour before we reach a hut. We can just about make out the presence of three men inside, but it's almost as dark as the balaclavas that hide their faces. In the identikit released by the Mexican government, Marcos was described as a professor with a degree in philosophy who wrote a thesis on Althusser and did a masterâs at Paris-Sorbonne University. A voice initially speaking French breaks the silence: âWeâve got twenty minutes. I prefer to speak Spanish if thatâs OK. Iâm Subcomandante Marcos. I'd advise you not to record our conversation, because if the recording should be intercepted it would be a problem for everybody, especially for you. We may officially be in the middle of a ceasefire, but theyâre using every trick in the book to try and track me down. You can ask me anything you like.â

Why do you call yourself âSubcomandanteâ?

Everyone says: âMarcos is the bossâ, but thatâs not true. They're the real bosses, the Zapatista people; I just happen to have military command. They've appointed me spokesperson because I can speak Spanish. My comrades are communicating through me; Iâm just following orders.

Ten years off the grid is a long time. How do you pass the time up here in the mountains?

I read. I brought twelve books with me to the Jungle. One is Canto General by Pablo Neruda, another is Don Quixote .

What else?

Well, the days and years of our struggle go by. If you see the same poverty, the same injustice every single day... If you live here, your desire to fight and make a difference can only get stronger. Unless youâre a cynic or a bastard. And then there are the things that journalists donât usually ask me. Like, here in the Jungle, we sometimes have to eat rats and drink our comradesâ piss to ensure we don't die of thirst on a long journey...things like that.

What do you miss? What did you leave behind?

I miss sugar. And a dry pair of socks. Having wet feet day and night, in the freezing cold...I wouldn't wish that on anyone. As for sugar, it's just about the only thing the Jungle can't provide. We have to source it from miles away because we need it to keep our strength up. For those of us from the city, it can be torture. We keep saying: âDo you remember the ice creams from Coyoacán? And the tacos from Division del Norte ?â These are all just distant memories. Out here, if you catch a pheasant or some other animal, you have to wait three or four hours before it's ready to eat. And if the troops are so famished they eat it raw, itâs diarrhoea all round the next day. Life's different here; you see everything in a new light... Oh yes, you asked me what I left behind. A metro ticket, a mountain of books, a notebook filled with poems...and a few friends. Not many, just a few.

When will you unmask yourself?

I don't know. I believe that our balaclava is also a positive ideological symbol: this is our revolution...it's not about individuals, there's no leader. With these balaclavas, we're all Marcos.

The government would argue that youâre hiding your face because youâve got something to hide...

They don't get it. But itâs not even the government that is the real problem; it's more the reactionary forces in Chiapas, the local farmers and landowners with their private âwhite guardsâ. I don't think thereâs much difference between the racism of a white South African towards a black person and that of a Chiapaneco landowner towards a Mexican Indian. The life expectancy for Mexican Indians here is 50-60 for men and 45-50 for women.

What about children?

Infant mortality is through the roof. Let me tell you the story of Paticha. A while back, as we were moving from one part of the Jungle to another, we happened upon a small, very poor community where we were greeted by a Zapatista comrade who had a little girl aged about three or four. Her name was Patricia, but she pronounced it âPatichaâ. I asked her what she wanted to be when she grew up, and her answer was always the same: âa guerrillaâ. One night, we found her running a really high temperature â must have been at least forty â and we didn't have any antibiotics. We used some damp cloths to try and cool her down, but she was so hot they just kept drying out. She died in my arms. Patricia never had a birth certificate, and she didn't have a death certificate either. To Mexico, it was as if she never existed. Thatâs the reality facing Mexican Indians in Chiapas.

The Zapatista Movement may have plunged the entire Mexican political system into crisis, but you haven't won, have you?

Mexico needs democracy, but it also needs people who transcend party politics to protect it. If our struggle helps to achieve this goal, it won't have been in vain. But the Zapatista Army will never become a political party; it will just disappear. And when it does, it will be because Mexico has democracy.

And if that doesnât happen?

Weâre surrounded from a military perspective. The truth is that the government won't want to back down because Chiapas, and the Lacandon Jungle in particular, literally sits on a sea of oil. And itâs that Chiapaneco oil that Mexico has given as a guarantee for the billions of dollars it has been lent by the United States. They canât let the Americans think they're not in control of the situation.

What about you and your comrades?

Us? Weâve got nothing to lose. Ours is a fight for survival and a worthy peace.

Ours is a just fight.

2

Peter Gabriel

The eternal showman

Peter Gabriel, the legendary founder and lead vocalist of Genesis, doesn't do many gigs, but when he does, he offers proof that his appetite for musical, cultural and technological experimentation truly knows no bounds.

I met him for an exclusive interview at Sonoria, a three-day festival in Milan dedicated entirely to rock music. During a two-hour performance of outstanding music, Gabriel sang, danced and leapt about the stage, captivating the audience with a show that, as always, was much more than just a rock concert.

At the end of the show, he invited me to join him in his limousine. As we were driven to the airport, he talked to me about himself, his future plans, his commitment to working with Amnesty International to fight racism and social injustice, his passion for multimedia technology and the inside story behind Secret World Live , the album he was about to launch worldwide.

Do you think the end of apartheid in South Africa was a victory for rock music?

It was a victory for the South African people, but I do believe rock music played its part.

In what way?

I think that musicians did a lot to make people in Europe and America more aware of the problem. Take Biko , for example. I wrote that song to try and get politicians from as many countries as possible to continue their sanctions against South Africa and keep up the pressure. It's about doing small things; they might not change the world, but they make a difference and it's something we can all get involved in. Fighting injustice isn't always about big demonstrations or grand gestures.

What do you mean?

Let me give you an example. There are a couple of elderly ladies in the Midwest of the United States who annoy the hell out of people who inflict torture in Latin America. They spend all their time firing off letters to prison directors, one after another. Because they're so well-informed, their letters are often published prominently in the American newspapers. And it often just so happens that the political prisoners they mention in their letters are suddenly released, as if by magic! Thatâs what I mean when I talk about how little things can make a difference. Basically, the music we make is the same as one of their letters.

Your commitment to fighting racism is closely linked to the work of your Real World label, isnât it, which promotes world music?

Absolutely. It's given me immense satisfaction to bring such diverse musicians together from places as far apart as China, Africa, Russia and Indonesia. We've produced artists such as the Guo Brothers from China and Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan from Pakistan. I've taken so much inspiration from their work, as well as from other artists on the Real World label. The rhythms, the harmonies, the voices... I had already begun to head in that direction as early as 1982, when I organised the first WOMAD [World of Music, Arts and Dance] festival. The audience were able to take part in the event, playing on stage alongside groups from Africa. It was such a meaningful, life-affirming experience that the festival has since been held in other parts of the world, including Japan, Spain, Israel and France.

Is that why some people call you the âfather of world musicâ?

Real World and world music are commercial labels above everything else; we publish music from artists the world over so that their music can be heard the world over, on radio stations and in record stores. But I want the artists who record an album on my label to become famous in their own right. No one says âis this reggae?â any more; they say âis this Bob Marley?â. In time, I hope that no one who hears a song by one of my artists asks âis this world music?â

You've recently shown a great interest in multimedia technologies, and your interactive CD âXplora1â has really got people talking. How does all this fit in with the activities of Real World?

There's so much you can do on that CD, like choose tracks by each individual artist just by clicking on the album cover. But I want to see so much more of this kind of thing; interactivity is a great way of introducing people to music. Essentially, what Real World is trying to do is blend traditional, analogue music, if you will, with the new digital possibilities that modern technology gives us.

Are you saying that rock music itself isn't enough any more? That it needs some kind of interaction with the listener? Do you want everyone to play a part in creating the final product?

Not always. For example, I tend to listen to music in my car and I don't want to need a screen or a computer to do that. But when Iâm interested in an artist or I want to know more about them, where they come from, what they think, who they really are, thatâs when multimedia technology can offer me some relevant visual material. Basically, in the future I would like to see all CDs offering this dual functionality: you can either simply listen to them, or you can âexploreâ them. With Xplora1 , we wanted to create a little world in which people could move around, make choices and interact with the environment and the music. There's loads of things you can do on the CD. Like take a virtual tour of the Real World recording studios, get access to events like the Grammys or the WOMAD festival, listen to live tracks, learn about my career from the early days with Genesis until the present day, and even remix my songs to your heartâs content!

And also have a virtual rummage in your wardrobe, right?

Absolutely ( laughs ). You can have a rummage in Peter Gabriel's wardrobe!

All this seems light years away from your experience in Genesis. What has stayed the same since those days? Have you never wanted, for example, to do another rock opera like âThe Lamb Lies Down on Broadwayâ? Have you moved on from all that?

Good question. I think Iâm still interested in some of those ideas, but in a different way. In one way, the things I was trying to do during my final years with Genesis were linked to the idea of being multimedia. Itâs just that back then, sound perception was restricted by the technology of the time. Now, I want to go a lot further down that road.

Going back to your political and humanitarian activities, now that apartheid is over, what are your other causes célèbres? What global injustices are you looking to rail against?

There are loads. But right now, I think the most important thing is to help people get their voices heard. Everyone should be able to appear on TV or have access to means of communication such as fax machines or computers. Basically, I think we have a chance today to use network communication technology to better defend peopleâs human rights.

That's very interesting. Can you give a concrete example?

I want to set small, tangible goals. Like making sure a particular village has phone lines, twenty or thirty PCs, that kind of thing. You can set that kind of equipment up almost anywhere in the world - India, China, up a mountain, wherever... Within three or five years, the people living in these places could learn how to create, manage and process information. With just a little bit of hard work, we could transform the economies of many countries from being based on farming to being based on information. That would be a huge step.

So, what next for Peter Gabriel?

A holiday ( laughs ). Weâve been on tour for months. Weâve had the odd break, but I think I need to get away. On tour, there's always time pressure and the stress of travelling...and I don't get time to play any sport. I mean, I love to play tennis. As far as work is concerned, Iâm thinking about doing something similar to the interactive CD. I've just finished my new album, Secret World Live , which was recorded over the course of this long tour. Itâs an overview of my career to date, kind of like an anthology. The only track that hasnât been on one of my previous studio albums is Across The River . Basically, the album is also a way for me to thank all those people who have performed with me on this back-breaking tour. There's the usual suspects like Tony Levin and David Rhodes, but also Billy Cobham and Paula Cole, who accompanied me in Milan, Billy on the drums and Paula on vocals.

Do you have a dream?

I do. I wish there was already a United States of Europe.

Why?

Because it has become clear that small countries can no longer be important to the global economy. We need an organisation that protects their cultural identity and represents them on the world stage and the financial markets. In order to survive, and in particular to compete with places that can offer cheap manual labour, these countries need solid economic representation and a proper commercial union. We also need to stop dividing the world into two groups: the traditional Anglo-Saxon elite and poor countries that are there purely to be exploited. We should be celebrating the differences between people in each individual country, not trying to make everybody the same.

3

Claudia Schiffer

The fairest of them all

She was the most beautiful and highly paid woman on earth, and probably also the most censored. âIâm the only model who's never been photographed toplessâ, she used to boast. Even her multi-million-dollar contract with Revlon forbade her from posing nude.

But everything changed when two Spanish photographers from the Korpa Agency lifted the veil, allowing the whole world to admire the legendary Claudia Schiffer's perfect breasts. The international press had a field day; only German weekly Bunte spared her blushes on the cover, and even they plastered the topless photos on a multi-page spread inside the magazine. Claudia protested furiously and announced she would be suing and seeking astronomical damages.

I had a couple of contacts in the fashion industry, so I decided to strike while the iron was hot and try to arrange an interview with her for the Italian weekly Panorama . It was certainly no cakewalk, but after dozens of phone calls and protracted negotiations with her obstructive agent, my persistence was rewarded in August 1993, when I was invited to interview Claudia on a family holiday in the Balearics.

This was a genuine scoop. Claudia had never previously spoken to the Italian press and I was the first journalist to be invited into the intimate family surroundings of her holiday home. This was the very place where the photos at the centre of the scandal had been taken: Port dâAndratx, an exclusive resort west of Palma on the island of Majorca, and the location for many years of a holiday home belonging to the Schiffer family.

In 1993, Claudia had a particularly good reason for heading down there to relax. She had just finished playing herself in a long film / documentary entitled Around Claudia Schiffer, directed by Claude Lelouch's former assistant director Daniel Ziskind and filmed in France, Germany and the United States. Filming had just ended, and TV stations the world over were scrambling to acquire the rights.

Just before I set off, I let it slip (probably not entirely by accident, if Iâm honest) to a rather wealthy friend whose family owned a renowned tool company that I was going to Palma de Majorca to meet Claudia. At which point my friend assured me I wouldnât need to book a hotel: âI've got a [magnificent hundred-foot sailing] yacht down there. There are five sailors and a cook swanning round Palma right now at my expense with nothing to do. At least if you head down there, theyâll have to work for their money! And youâll get to enjoy a nice little cruise from Palma down to Port dâAndratx!â

I didnât need a second invitation, and so on the day of the interview I stepped down off my buddy's yacht on to the marina at Port dâAndratx after a two-hour journey from Palma. Giving a cheery wave to the crew, I headed for Café de la Vista, a nice little spot opposite the throng of moored yachts, where I was scheduled to meet Claudia at three-thirty.

Surely no journalist had ever arrived for an interview in such style!

*****

I donât have to wait long before an Audi 100 with a Düsseldorf plate rolls up. Theyâre here. Two men are in the front, and on the back seat I can see her ever-present agent Aline Soulier. âWhere is she?â I wonder anxiously. Iâm not disappointed for long. A wavy-haired blonde appears from behind Aline and leans forward in her seat. âHi, Iâm Claudia,â she says, extending her hand and flashing me a smile. She's astoundingly beautiful, a mesmerising mix of Lolita and the Virgin Mary.

No one gets out of the car. âThere are paparazzi everywhere,â whispers Aline as we make the short journey to the family holiday home, a brick-red, single-storey villa. Leading the way, Claudia tells me I am the first reporter she has ever invited here, before introducing me to her family: âThis is my little brother, my sister Carolin, my mother.â Claudiaâs mother has a typically German look: short blonde hair, very refined and standing even taller than her five-foot-eleven daughter. Her father, a lawyer practising in Düsseldorf, is not here. Those in the know say he is the one who has orchestrated her success from the shadows, the man responsible for her fame as one of the worldâs most beautiful women.

It all started for you in a Düsseldorf night club, didnât it?

I was so young. One night, I was approached by the head of the Metropolitan agency, who asked me to work for him.

How did you react?

I said to him: âIf youâre being serious, you can talk to my parents tomorrow.â I mean, people try all sorts of different chat-up lines in clubs. That could easily have been another, and not a very original one at that...

Are you close to your family?

Very. As a family, we have our feet on the ground. My father is a lawyer and my mother helps him with the admin side of things. They haven't been changed by my success; it takes a lot to impress them. Of course, theyâre very proud of me, but to them it's just my job and they expect me to do it to the best of my ability.

Aren't your siblings jealous?

Of course not! Theyâre just proud of me, particularly my twelve-year-old brother. I have a sister whoâs 19 and goes to university, so there's no competition between her and me, and finally I have a twenty-year-old brother and we get on great.

Do you always come on holiday with them to Majorca?

I have done ever since I was very young. I love this place.

But now you're older, it looks like you find it hard just being able to go out for a walk around here...

You're right. There are paparazzi everywhere, hiding in plants; itâs embarrassing. Every move I make is observed, studied, photographed... Itâs not exactly a holiday if you look at it like that! (laughs ).

I suppose thatâs the price of fame...

Exactly. But I often go out on the boat with my mum and my brothers and sisters. I feel like they can't hassle me as much at sea.

Really?

Oh, you mean the topless shots? I honestly donât understand how that could have happened. I was out on the boat with my mum and my sister Carolin. We were anchored and taking the chance to soak up some sun. Peter Gabriel was also there. Heâs a dear friend of mine...

We saw...

Well, there you go. He was also in the photos. But Iâd rather not talk about it. Anyway, Iâve already instructed my lawyers to seek damages...

People say you'd like to become an actress.

Iâd like to give it a go, thatâs all. People keep offering me scripts, and the more I read the more I want to have a go... Right now Iâd love to do a film. I really would.

But you won't be appearing in Robert Altman's film Prêt-à -porter next year?

Itâs absolutely unbelievable. The press all over the world keep talking about it, but itâs categorically not true. Plus, I donât want to do a film where Iâm just playing myself.

If you had to choose between a supermodel and an actress, what would you be?

You can't be a model all your life. Itâs a career for really young girls and you can only do it for a few years, a bit like playing tennis or swimming. So you need to make hay while the sun shines. Afterwards, I'd also like to go to university and study art history.

You've always said you will defend your privacy at all costs. Isnât it a bit of a contradiction doing this documentary about your life, in your home, your parentsâ home?

I donât think so. The truly private moments will remain as such. In the film, you only see what I have consciously chosen to reveal: my family, my friends, my holidays, my hobbies... Basically, the things I love. And then there's also all the travelling around, the fashion shows, my photographers, the press conferences...

Do you live sometimes in Paris and sometimes in Monte Carlo?

Essentially, I live in Monte Carlo. I always go back there when Iâm not working, at weekends for example.

Does your agent travel everywhere with you?

Not normally. I need her when I have to work in countries that Iâm not familiar with. Like Argentina, Japan, Australia or South Africa. In those places, there are so many fans, reporters, paparazzi...

Does it get tedious travelling around so much?

No, because I love reading and a good book always makes the time pass more quickly, even on a plane. Plus, itâs my job; itâs not a holiday!

What sort of books do you read?

Mainly books about art. My favourite movements are Impressionism and Pop Art. I also really like history and reading biographies of great men and women. I read one on Christopher Columbus. It was incredible!

People have said youâre half Brigitte Bardot and half Romy Schneider. Do you think that's fair?

Yes, although not so much physically. Itâs more that I think I share certain aspects of their character and lifestyle... I find Bardot an extraordinary woman as well as incredibly beautiful. What a character! I also kind of worship Romy Schneider. I've seen all her films and it was just horrible when she died. Such a tragic life...

Apart from the tragic events, would you like to be the new Romy Schneider?

Wow, what a compliment! Being compared to all these beautiful women. Itâs really flattering, but above all I just want to do everything I can to be me.

What did you want to be when you were growing up?

I certainly didn't think I would become a model. I guess I wanted to be a lawyer.

Like your father?

Yeah, I was all set to go and work for his firm. And then all my plans changed. I realised this was too good an opportunity to turn down, so I grabbed it with both hands.

Your story is a bit of a fairytale for the modern ages. There must have been some tough times?

Oh, sure. But Iâm always confident in my own ability.

Whatâs your secret?

Plenty of discipline. And also being able to be around others. Iâm a people person. I like being able to think on my feet when Iâm facing a barrage of questions from reporters at a press conference. I see it as a challenge; it doesn't scare me.

Is it just about discipline?

You also need to stay level-headed. And thatâs where the way I was brought up comes in. My family have helped me a lot. They made me who I am: confident, pragmatic and well-balanced. I can stay in control even when Iâm out of my comfort zone. For example, itâs thanks to my parents that Iâm now able to speak in public without feeling shy.

If the media is anything to go by, you move pretty quickly from one relationship to another: one day itâs Prince Albert of Monaco, the next Julio Bocca. Who is the real Claudia?

The real Claudia is a girl who has lots of friends. Prince Albert is one of those, Julio Bocca is another. But thereâs also Plácido Domingo, Peter Gabriel and a load of other famous people. As soon as Iâm photographed with them, I have the entire worldâs press immediately claiming they're my boyfriend! Itâs not like that.

But do you eventually see yourself settling down, getting married, having kids?

Iâm absolutely ready to fall in love, the sooner the better. But I don't have a partner right now simply because Iâve not fallen in love with anyone.

What do you look for in a man?

I don't have an ideal type in terms of looks. The first thing I look for is personality, and sense of humour above everything. I need a man to charm me, to win me over with intelligence, with his mind. Someone who can teach me the true value of humour. I mean, you have to be able to laugh, don't you?

Sounds like a pretty demanding job being your boyfriend â¦

Anyone who is with a celebrity needs to be a strong character in their own right. I love men who have character but are also sensitive. If you want to be with me, you have to tolerate noise, intrusion, gossip, reporters...

Do you feel guilty at all?

What do you mean?

I mean, it seems like you have it all: beauty, fame, money...

I do feel lucky. I thank God and my parents for giving me the life I have. Thatâs why, when I can, I try to do something useful or helpful.

But it's not all sunshine and roses in the fashion world, is it? Thereâs drugs, alcohol, fierce rivalries...

Iâm not affected by drugs or alcohol. Jealousy, sure, but I donât really understand it. Models come in all shapes, sizes, personalities and mentalities, so I think there's room enough for everyone. And you donât have to be insanely beautiful. There's something beautiful about every woman. You just have to nurture it.

What do you need to make it big?

The main thing is character, because itâs not like there is a shortage of beautiful women in the world. After that, you need education, personality and discipline.

By that, do you also mean discipline when it comes to your diet?

Not really. I donât smoke and I don't drink, but thatâs only because neither thing appeals to me. I donât eat a lot of meat because I don't think itâs good for you, and Iâm careful about fats. But I love chocolate... Oh, and Fanta of course! (laughs ).

How are you with money?

Itâs not the be all and end all, but it will allow me to do what I want in the future. Money gives you freedom.

What does the word sex mean to you?

To me? (seems genuinely taken aback ).

Yes, to you.

Well, something that happens naturally between two people who are in love with each other. That's it.

Do you feel like you're a particularly sexual, or rather sensual, person?

Absolutely.

? yes!

4

Gong Li

Moonstruck

In early 1996, I had just started to work as a Far East correspondent. I and other journalist friends of mine would meet up with John Colmey, who was working for Time in Hong Kong. John put me in touch with the manager of the glamorous Chinese actress Gong Li, and I managed to get an exclusive interview with her for Panorama on the set of the movie she was filming near Shanghai.

*****

We are in Suzhou, a city on the shores of Lake Tai about fifty-five miles west of Shanghai, where Chen Kaige is preparing to shoot one of the final scenes of Temptress Moon , a film that is keenly anticipated following the global success of Farewell My Concubine three years ago. Crew members are scurrying between what must be more than two hundred extras dressed in 1920s clothing and crowded onto the jetty. The women are wearing typical silk cheongsams, some of the men are sat in sedan chairs reading and, in the background, dockers are loading cargo onto a steamer. They are filming a big farewell scene: Gong Li plays Ruyi, a beautiful and pampered heiress of an extremely wealthy Shanghai family beset by incest, opium abuse and double-crossing. She is about to set sail for Peking with her fiancé Zhongliang, played by Leslie Cheung, the Hong Kong actor whom she also starred alongside in Farewell My Concubine .

Stood on the jetty is Ruyi's childhood friend Duanwu (played by up-and-coming Taiwanese star Kevin Lin), who has secretly been in love Ruyi all along: âYou have to imagine this is the last time you will see her, the very last time! We need to see that in your face; thatâs what I want to see!â urges the forty-six-year-old Chen, who is wearing a leather jacket and black jeans. âRight... Yu-bei ... [Ready...] Action !â As Kevin Lin looks over at the departing ship, his pain is clear to see. â Okay! â yells a satisfied Chen. Thatâs a wrap for the day.

Having spent more than two years writing the script, Chen is working his backside off to get his film ready for the Cannes Festival in May. The son of Chen Huaiâai, himself a giant of post-war cinema, Chen is currently the leading figure in the Chinese film industry and has a reputation for getting the most out of his actors, sometimes stretching their patience to the limit. Just as he has done with the Chinese government, who banned, cut and censored his films for years before eventually acknowledging his status as a maestro of contemporary cinema.

At a cost so far of six million dollars, Temptress Moon to a certain extent represents the current status of the Chinese film industry: no longer totally repressed but not yet fully liberalised, shown across the globe but with its feet firmly planted in China, and simultaneously cosmopolitan yet parochial. And the film set appears to be a microcosm of modern-day China.

The stars of the film are the current cream of the crop from the âthree Chinasâ: Hong Kong (Leslie Cheung), Taiwan (Kevin Lin) and the Peopleâs Republic of China (Gong Li). The Director is an intellectual from Beijing and the producer, Hsu Feng, is a former star of Taiwanese cinema married to a businessman from Hong Kong, where she set up Tomson Films in the eighties. Indeed, it was Hsu who persuaded Chen eight years ago to bring Lilian Lee's novel, Farewell My Concubine , to the big screen.

While there is considerable hype about Chenâs latest directorial outing, what the critics and public are most excited about is the casting of the undisputed star of the film, Gong Li. The thirty-one-year-old actress is currently, without question, the most famous Chinese woman in the world. Her previous films include Red Sorghum (1987), Raise the Red Lantern (1991) and Farewell My Concubine (1993). She has just come out of an eight-year relationship with Zhang Yimou, the director who made her a global star and with whom she made her last film, Shanghai Triad , last year.

Despite Gongâs success in the West, she remains Chinese through and through.

After the dayâs filming had ended, she agreed to meet me for an exclusive interview for Panorama .

Another big film for you and another old story, this time set in 1920s China . Why do you think that is?

I think it's because China has only recently opened its doors to the rest of the world. Ever since, Chinese cinema has enjoyed greater stylistic and cultural freedom. Censorship obviously played a defining role in Chinese cinema and the topics it covered for years, but there's also a more artistic explanation, if you can call it that: many Chinese directors think itâs a good idea to make films about events that pre-date the Cultural Revolution. It's a way of revisiting those events and that era. And maybe they think it's still a bit early for an international audience to see films about recent events, which are still too fresh and painful in people's memories.

Youâre the most famous Chinese woman in the world. Do you feel the responsibility of being an ambassador?

The term ambassador scares me a little, if Iâm honest. Itâs too grand for me! Let's just say I feel that, through my films, I can be a bridge between Chinese and Western culture and history. I think it's fair to say that you guys don't know a great deal about modern China. So it gives me a great sense of pride to think that one of my films can help to educate the West about our people and the way we live our lives.

Sadly, the world's image of China in recent times is mass executions and orphanages with their âdying roomsâ. Is that really what it's like?

China has plenty of problems, there's no getting away from that. Especially if you choose to only look at the negatives and ignore the positives. If you only see one side of a country, you're not seeing the complete picture. China is a massive country with over a billion people, so there are huge differences within it. You canât just make sweeping judgements.

When did you accept the part of Ruyi in Temptress Moon ?

It was luck, really. Or maybe fate. They'd already started filming when a Taiwanese actress quit, so they offered me the part at the last minute. Did you know the Chinese critics are comparing Temptress Moon to Gone with the Wind ?

Are they? Why is that?

Itâs not because of the story; itâs the casting. Chen auditioned dozens of actresses for my role, just like several actresses were cast aside before they chose Vivien Leigh to play Scarlett O'Hara. So theyâd already begun filming when I joined the production. It's not been easy. Iâm playing a spoiled little rich girl, which is nothing like my usual roles.

This is a golden age for Chinese cinema, isn't it? You've got directors like Chen and actors like you, but there's also people like John Woo and Ang Lee making it big in Hollywood .

I think it's because Chinese directors can combine exemplary cinematography with our culture's unique charm and style.

How did you get into acting?

Completely by chance. I loved to sing when I was younger. One day, my singing teacher said I should go with him to watch a TV show being filmed in Shandong. I remember the director was a woman. When she saw me, she decided I had to have a part, so she gave me a copy of the script. It was only a small part, but she decided I was a natural. She said to my mum: âYour daughter must become an actress.â She managed to convince her, and two months later I enrolled at the Central Academy of Drama in Beijing. I studied really hard, started to get small parts and the rest, as they say, is history!

You divide your time between Beijing and Hong Kong. The papers are full of your new relationship with a Hong Kong-based businessman, so do you think you will move there permanently?

I donât think so. I like Hong Kong because itâs bustling and great for shopping. But I find it annoying. Beijing is different. People stop you in the street and talk to you about all sorts. In Hong Kong, itâs all about the money.

Are you fed up with the press sticking their noses into your private life?

I think it comes with the territory really. Itâs mainly the Asian press that often prints unpleasant or made-up stories. The papers in the West have higher standards.

Is it also important for an actress to be beautiful in China?

Do you think Iâm beautiful?

Youâre seen as a sex symbol in the West .

Thatâs really nice, but I don't feel like a sex symbol. Maybe Chinese women have a certain appeal or charm because we are so different to Western women.

What are your plans for the future?

I want to get married and have children. I think family is a really important part of a womanâs life. If you donât have a family, you canât bring experience of everyday life into your work.

And do you have any more films lined up?

Not at the moment. Iâm reading lots of scripts, but none have jumped out at me so far. Iâm not going to accept any old part just for the sake of it.

Would you consider working with a Western director?

If they had a part that was suitable for me as a Chinese woman, sure...why not?

Is there an Italian director youâd like to work with?

Absolutely: Bernardo Bertolucci!

5

Ãngrid Betancourt

The Pasionaria of the Andes

Dina, here is my article with box to follow. I hope you are well.

Today (Monday, February 11), Iâm flying from Tokyo to Buenos Aires, where I will land tomorrow (February 12). You will still be able to reach me on my satellite phone, even while Iâm navigating my away across Antarctica. Iâll be back in Argentina around February 24 and will then head to Bogotá, where I am scheduled to interview Ingrid Betancourt in early March.

Let me know if you'd be interested.

Catch up soon,

Marco

On an old computer, I found this email that I sent in early February 2002 to inform Dina Nascetti, one of my bosses at LâEspresso , of my movements. I had been in Japan to report on the tomb of Jesus

and I was preparing to embark on a long journey that would take me far away from home for nearly two months. I was headed for the end of the Earth: Antarctica.

On the way out, I planned to report on the severe economic crisis that was gripping Argentina, and on the way back, I would go via Colombia to interview Ingrid Betancourt Pulecio, the Colombian politician and human rights activist. As it turned out, I arrived in Bogotá a couple of days early, which - for me at any rate - was a stroke of luck. I interviewed Ms Betancourt on February 22, and precisely twenty-four hours later she vanished into thin air while being driven from Florencia to San Vicente del Caguán. She had been kidnapped by FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) guerrillas and would be held hostage for more than six years.

If Iâd arrived in Colombia just a day later, I never would have met her.

*****

She has shoulder-length brown hair and typically Colombian dark eyes. She wears an amber bracelet on her wrist and rarely cracks a smile.

But then, Ãngrid Betancourt doesnât have many reasons to smile. She may look younger than her forty years and have an enviable petite frame, but she is running for the presidency of Colombia, the most violent country in the world, where ten people are kidnapped and seventy people murdered every single day. Where war has raged for four decades, claiming thirty-seven thousand civilian lives in the last twelve years alone. A country that boasts the dubious honour of being the worldâs leading producer of cocaine. A country from which over a million people have fled in the last three years.

And yet, it is not so long ago that this same woman sat before me today in a heavily guarded, clandestine apartment in downtown Bogotá, wearing a bulletproof vest and a nervous expression, was smiling serenely as she lay on a beach in the Seychelles, where her handsome and sophisticated French diplomat husband had been posted.

Precisely twenty-four hours after the interview, while being driven from Florencia to San Vicente del Caguán, on the front line of the battle between FARC rebels and government forces, Ãngrid Betancourt disappears along with a French photographer and cameraman accompanying her to document an electoral campaign fraught with danger. Everything points to a kidnapping.

A dramatic event which paradoxically, even for a country as pitiless as Colombia, âsuddenly increases the likelihood of her winning the electionâ, Gabriel Marcela, professor at national war college ESDEGUE, knowingly observes.

It was Ms Betancourt's own decision to come back to this hellish place in 1990, aged just thirty and in the prime of her life.

A former member of the Chamber of Representatives she has founded the Oxygen Green Party âin order to bring clean air into the corrupt world of Colombian politicsâ, she explains solemnly. The partyâs slogan reads: â Ãngrid es oxigeno â [Ãngrid is oxygen]. And the campaign poster shows the woman herself with an anti-smog mask and surrounded by coloured balloons. The one hundred and sixty thousand votes she received when she was elected Senator four years ago were the most for any candidate in a Senate election in Colombia. But it could be argued that she wouldn't still be in the headlines without her recently published autobiography, the Italian title of which leaves us in no doubt as to her current frame of mind: Theyâll Probably Kill Me Tomorrow .

I put it to her that this might be a shade melodramatic.

â The French edition was titled La rage au coeur [With Rage in My Heart],â she responds defensively. âBut the Italian publishers wanted a stronger title, so that's what we went for. And actually, thatâs really how Iâm feeling. It's what goes through my head first thing in the morning and last thing at night. I donât think itâs particularly melodramatic. The prospect of being murdered tomorrow is a very real one for millions of this people in this country.â

The French newspapers are portraying her as some kind of latter-day saint: Paris Match called her âThe woman in the firing lineâ, Libération âA heroineâ, Le Figaro âThe Pasionaria of the Andesâ. Le Nouvel Observateur wrote: âif Simon BolÃvar, the liberator of Latin America, could have chosen an heir, he would have chosen herâ.

Whereas the Colombian press have had a laugh at her expense. Semana , the countryâs leading weekly news magazine, lampooned her on the cover as Joan of Arc, complete with horse, armour and lance. The truth is, her book is far more measured and dry than its title and reviews would suggest. Ms Betancourt makes no attempt to hide her privileged background. As a young girl, she would ride horses every week at a farm owned by friends.

But she is full of ideas and has no difficulty putting them into words. âConservative estimates suggest that in 1998, Colombia's biggest guerrilla group, FARC, received annual funding of about three hundred million dollars, most of which came from drug trafficking, kidnapping and extortion. Today, that figure is close to half a billion dollars, and its membership has increased from fifteen thousand to twenty-one thousand. This situation,â she continues, âis putting the Colombian government at a huge disadvantage in their fight against the rebels. In order to secure a decisive victory, we believe that the government would have to deploy three or four highly trained soldiers for each FARC guerrilla, whereas the most they can currently send out is two. And all this requires an economic outlay that my country simply canât afford. Since 1990, the cost of suppressing the rebels has increased nearly ten fold. At the beginning, it was costing one per cent of GDP but now it is more than two per cent - one billion US dollars...it's astronomical.â

So is she a hot-headed fanatic, like her enemies claim, or simply a woman who wants to do something for her country, which is how she sees it? The political elite in Bogotá are trying to ignore her candidature, but they are gradually starting to fear her. Omar, her chief bodyguard, pipes up: âIn this country, you can pay for honesty with your life.â Ms Betancourt interjects quickly: âIâm not afraid of dying. Fear keeps me on my toes.â

Fighting corruption is at the forefront of her campaign, closely followed by the civil war. âThe State should have no qualms about negotiating with the left-wing guerrillas,â she concludes, âunlike the right-wing paramilitary group the AUC, which is responsible for most of the murders that take place in Colombia.â

So how does she live with fear and threats on a daily basis?

â I think, in a funny kind of way, you get used to it. Not that you should have to. The other day,â she concludes calmly, âI received a photo of a dismembered child in the post. Underneath it was written: âSenator, we have already hired a hit man to take care of you. Weâre reserving special treatment for your sonâ¦ââ.

6

Aung San Suu Kyi

Winner of the 1991 Nobel Peace Prize

Free from fear

Following considerable pressure from the United Nations, Aung San Suu Kyi was released on 6 May 2002. It made headlines around the world, but her freedom was short-lived. On 30 May 2003, a group of soldiers opened fire on her convoy, killing many of her supporters. She survived thanks to the quick reflexes of her driver Ko Kyaw Soe Lin, but she was again put under house arrest.

The day after her release in May 2002, I used some of my contacts within the Burmese opposition to arrange an interview with Ms Suu Kyi vie email.

*****

At ten oâclock yesterday morning, the guards stationed outside the home of Aung San Suu Kyi, the leader of the Burmese opposition National League for Democracy (NLD), quietly returned to their barracks. And so it was, in a surprise move, that the military junta in Rangoon lifted the restrictions it had placed on the movement of the pacifist leader known simply in her homeland as âThe Ladyâ, a woman who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991 and had been under house arrest since 20 July 1989.

So ever since ten oâclock yesterday morning, after a period of nearly thirteen years, Aung San Suu Kyi has been free to leave her lakeside house, speak to whomever she wants, be politically active and see her children.

But is this really the end of the period of isolation for the Burmese Pasionaria? The exiled opposition still do not believe the grand declarations from the military junta, which said it was freeing Ms Suu Kyi unconditionally.

They would rather wait and see. And pray. Indeed, since yesterday, the Burmese diaspora have already held prayer demonstrations in Buddhist temples in Thailand and other parts of eastern Asia.

As for The Lady herself, she too has wasted little time. She was immediately driven to the headquarters of the NLD, which had won a landslide victory (nearly sixty per cent of the vote) in the 1990 elections while the governing National Unity Party (NUP) secured just ten of the four hundred and eighty-five seats. The military government annulled the results, outlawed the opposition (imprisoning or exiling its leaders) and violently suppressed any protests. Parliament was never convened.

The Italian edition of your autobiography is called Libera dalla paura [Free From Fear]. Is that how you feel now?

Yes, for the first time in more than a decade, I feel free. Physically free. Free to go about my business and think, above all. As I explain in my book, however, Iâve felt âfree from fearâ for many years. Ever since I realised that the tyranny here in my country could harm humiliate or even kill us, but they couldn't scare us anymore.

You've only just been released, but youâve said today that there are no conditions on your freedom and that the governing military junta has even authorised you to leave the country. Do you really believe that?

In a press release issued yesterday evening, a spokesperson for the junta spoke of âa new chapter for the people of Myanmar and the international communityâ. Hundreds of political prisoners have been released over the last few months, and the military has assured me that they will continue to set free those who, in their words, âdo not present a danger to societyâ. Everybody here wants to believe, wants to hope that this really is a sign of change. A sign that we are back on the path towards democracy, which was so suddenly and violently cut off in the coup of 1990. It is a path that the Burmese people have never forgotten.

Now that you have been freed, are you not scared of being expelled and distanced from your supporters?

Let me be clear: I will not leave. I am Burmese, and I turned down British citizenship precisely because I didnât want to give the regime any excuses. Iâm not afraid, and that gives me strength. But the people are hungry, which frightens them, and that makes them weak.

You have strongly denounced, on several occasions, the military's attempts to intimidate anyone who sympathises with the NLD. Is that still going on today?

According to the figures we have, in 2001 alone the army arrested more than one thousand opposition activists under orders from SLORC [State Law and Order Restoration Council] generals. Many others have been forced to resign from the League [NLD] after being submitted to intimidation, threats and other wholly unjustified and unlawful pressures. Their meticulous method is always the same: unleash units of government officials who go from door to door across the entire country asking citizens to leave the League. Those who refuse are blackmailed with the threat of losing their jobs, or worse. Many branches of the party have closed down, and the military checks the number of people who have quit on a daily basis. This shows how afraid they are of the League. Every one of us hopes that all this is now really over.

Did the military's decision to release you take you by surprise, or was it something they had been planning for a while because they were conscious of their global reputation?

Since 1995, Myanmar has gradually become less isolated. The University of Yangon has been reopened, and maybe there has been a slight improvement in living standards. But the daily reality remains violence, unlawfulness and oppression against dissidents, ethnic minorities in search of autonomy (Shan, Bwe, Karen) and, more generally, the majority of the Burmese people. Problems are mounting up for the military, both domestically and internationally. In the meantime, they continue to traffic in drugs until they can find another, equally lucrative, source of income. But what will that be? Myanmar is essentially a gigantic safe to which only the army knows the combination. It wonât be easy to convince the generals to share this wealth with the other fifty million Burmese.

At this stage, what are your terms for entering into dialogue?

We wonât accept anything - there has been talk, for example, of the generals calling an election - until the parliament that was elected in 1990 has been restored. My country is still paralysed with fear. There cannot be genuine peace until there is a genuine commitment that honours all those who have fought for a free and independent Myanmar, but we are well aware that ongoing peace and reconciliation requires ever greater vigilance, courage and the ability to resist actively but without resorting to violence.

What can the European Union do to help the people of Myanmar?

Keep applying pressure, because the generals have to know that the world is watching and will not allow them to commit more heinous crimes with impunity.

*****

Aung San Suu Kyi was finally released for good on 13 November 2010. In 2012, she won a seat in the Burmese parliament, and on June 16 of the same year, she was finally able to receive her Nobel Peace Prize in person. Finally authorised to travel abroad, she went to the UK to visit the son she had not seen for several years.

On 6 April 2016, she became State Counsellor (equivalent to Prime Minister) of Myanmar.

While it is true that Myanmar is not yet a totally free country, and its dictatorial past weighs on both its history and its future, there is no doubt that freedom and democracy are now more than just pipe dreams in the Land of A Thousand Pagodas.

7

LucÃa Pinochet

Death, torture and disappearance

Santiago, March 1999 .

â Pinochet? Chileans see him as a cancer. A hidden and painful illness. You know itâs there, but you're afraid to talk about it...to even say its name. So you end up pretending it doesnât exist. Maybe you think that by ignoring it, it will just go away without you having to confront it.â The waitress at Café El Biógrafo , a popular hangout for poets and students in the picturesque bohemian Santiago barrio of Bellavista, known for its colourful houses, couldn't have been much more than twenty years old. She may not even have been born when General Augusto Pinochet Ugarte, the â Senador vitalicio â [Senator-for-life] as he is known here, was either giving orders that would see his opponents âkilled, tortured and forcibly disappearedâ - as the families of the more than thirty thousand desaparecidos claim - or ruling with an iron fist to ensure that Chile was free from the threat of communism - as his admirers insist. And yet she is keen to talk to me about Pinochet, and she has some forthright views: âItâs all about Pinochet here. Whether you're a fan of his or not, you can't deny that he is present in every part of Chilean life. He's part of our politics, clearly. He lives large in everyone's memories, in my parentsâ stories, in teachersâ lessons. Heâs in novels, non-fiction books, the cinema. That's right, in Chile even films are either for or against Pinochet. And yet somehow we continue to pretend that he isnât there...â

This stubborn old man, who faced up to the British justice system âwith the dignity of a soldierâ, this âpoor old guyâ (as whispered into my ear by the concierge at the CÃrculo de la Prensa , where during the shadowy years of the military dictatorship, people loyal to the General would come to âpick upâ pesky journalists right in front of the Palacio de La Moneda, where Salvador Allende died in the midst of the coup) had become a lumbering giant whose presence was felt in every corner of every street of every quarter of Santiago, a city that seemed to me uncertain and inward-looking

He is the living memory of this country - a colossal, ubiquitous memory that embarrasses those who supported him and irritates those who opposed him. A vast, sprawling memory that clings to people's lives, hopes and fears, to Chile's past and to its future.

In October 1998, having retired as Commander-in-Chief of the Chilean army and been appointed Senator-for-life, Pinochet was arrested while in London for medical treatment and placed under house arrest. First at the clinic where he had just undergone back surgery, and then in a rented house.

The international arrest warrant had been signed by a Spanish judge, Baltasar Garzón, for crimes against humanity. The charges included nearly a hundred counts of torture of Spanish citizens and count of conspiracy to commit torture. The UK had only recently signed the United Nations Convention against Torture, meaning that all the charges related to events that occurred during the final fourteen months of his rule.

The Chilean government immediately opposed his arrest, extradition and trial. Thus began a hard-fought, sixteen-month battle in the House of Lords, then the highest court in the UK. Pinochet claimed diplomatic immunity as a former head of state, but the Lords refused in light of the severity of the charges and authorised the extradition, albeit with several restrictions. However, shortly afterwards, a second ruling by the Lords enabled Pinochet to avoid extradition on health grounds (he was eighty-two years old at the time of his arrest), for âhumanitarianâ reasons. Following medical assessments, the British Home Secretary Jack Straw authorised Pinochet to return to Chile in March 2000, nearly two years after he was put under house arrest.

It was at the end of March 1999, in the midst of this complex international legal battle, that I went to Santiago to monitor the situation for the daily Il Tempo and to interview Pinochetâs eldest daughter, LucÃa. The House of Lords had just rejected Pinochetâs claim for immunity, and the plane that the generalâs family and supporters had hoped would bring him home to Chile returned without him.

The reaction on the streets of Santiago was immediate. On March 24, the Chilean capital had awaited the ruling with bated breath. The city may not have been in lockdown, but there was a discrete Carabineros - military police - presence at potential flashpoints: the presidential seat at La Moneda, the British and Spanish embassies, and the headquarters of pro- and anti-Pinochet organisations. There was blanket media coverage, enabling Chileans to follow events minute by minute. With live satellite links to London, Madrid and various locations in Santiago starting at seven in the morning and lasting all day, it felt like a truly historical event. At around midday local time, less than an hour after the Lords had issued their ruling, two afternoon dailies were published in special edition. The headline of one of them put it very neatly: âPinochet loses but winsâ.

In the morning, the residents of Santiago had crowded round televisions in public places, from McDonald's to the smallest of bars, to follow all the crucial developments. Angry customers in one large city-centre store beseeched the manager to tune the TV into the live feed from London.

The situation had remained broadly calm until the late afternoon, when the first signs of tension began to surface. At four oâclock local time, there were the first clashes between students and the police in the city centre, at the crossroads between La Alameda

and Miraflores, with a dozen or so people injured and around fifty students arrested.

There were plenty of appeals for calm, mainly from members of the government. The inflammatory remarks from General Fernando Rojas Vender (the pilot who bombed La Moneda during the 1973 coup dâétat and the commander of the Chilean Air Force), who on the previous Tuesday had publicly stated that the climate in Chile was becoming âsimilar to how it was in 1973â had been condemned in the strongest terms by the government, which forced Rojas into a public retraction.

Now all eyes were on Mr Straw. The propaganda machine of Pinochetâs supporters was ready to roll, aiming to discredit the British Home Secretary whom they accused of publicly and forcefully endorsing the Chilean left on a trip to the country in 1966. Some people claimed they could prove that the young Mr Straw had held an informal meeting with the Chilean president at the time, Salvador Allende, who had invited him for tea.

As you can imagine, there were plenty of things I wanted to discuss as I made my way to LucÃa Pinochet's house.

*****

Inés LucÃa Pinochet Hiriart is Augusto's oldest daughter. She is an attractive woman who carries her age well and her tainted surname even better. The only reason she is not with her siblings in London, by her father's side, is that she has her leg in plaster. So she has been forced to stay in Santiago with the unenviable task of representing, and above all defending, the Senator-for-life.

We meet in her beautiful home in a well-to-do part of the city, and with her windows open we can hear demonstrators chanting pro-Pinochet slogans. With her three sons - Hernán, Francisco and Rodrigo - by her side, she speaks to me for nearly an hour, during which we cover the current situation with her father and, inevitably, the future of Chile as a whole.

What do you make of the âhumanitarianâ ruling that has just been given in your fatherâs case?

I would rather my father had been granted the full immunity he was entitled to as the former head of a sovereign state. Instead of a criminal trial, it has become a political debate about alleged torture, genocide and other crimes, bowing to pressure from socialists and people who claim they want to defend human rights.

Have you spoken to your father? How has he taken it?

My father is not happy about it. They had warned him about the possibility of a âhumanitarianâ ruling. And he's certainly not best pleased about Jack Straw handling the whole thing.

This is the man who people here claim took tea with Salvador Allende on a visit to Chile in 1966?

Exactly. Weâve known this for years. When they arrested my father in London, Straw said he had achieved a lifetimeâs ambition. Go figure.

So this has now shifted from being a legal case to a humanitarian one...

It's always been all about politics! It was nonsense ever talking about a trial; the only things on the agenda in London should have been presidential immunity and territorial sovereignty, not torture.