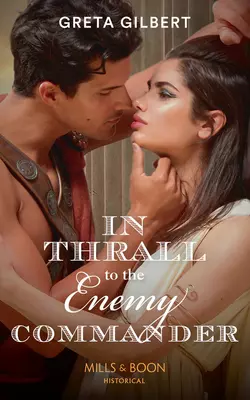

In Thrall To The Enemy Commander

In Thrall To The Enemy Commander

Greta Gilbert

Cleopatra’s slave girl…And an enemy Roman soldier…Egyptian slave Wen-Nefer is wary of all men. But she can’t help but be captivated by handsome Titus, advisor to Julius Caesar—even though he is commanding, and intolerant of bold women like her. Their affair is as all-consuming as it is forbidden. But is he a man who will go to any lengths to love her despite their boundaries…or a sworn enemy she must never trust?

Cleopatra’s slave girl

and an enemy Roman soldier...

Egyptian slave Wen-Nefer is wary of all men. But she can’t help but be captivated by handsome Titus, adviser to Julius Caesar, even though he is commanding and intolerant of bold women like her. Their affair is as all-consuming as it is forbidden. But is he a man who will go to any lengths to love her despite their boundaries...or a sworn enemy she must never trust?

“Gilbert’s passion for ancient history imbues her tales with authenticity [and] immerses readers in a long-lost culture.”

—RT Book Reviews on The Spaniard’s Innocent Maiden

“Gilbert’s desert romance is a tale to prize... Definitely a must.”

—RT Book Reviews on Enslaved by the Desert Trader

GRETA GILBERT’s passion for ancient history began with a teenage crush on Indiana Jones. As an adult she landed a dream job at National Geographic Learning, where her colleagues—former archaeologists—helped her learn to keep her facts straight. Now she lives in South Baja, Mexico, where she continues to study the ancients. She is especially intrigued by ancient mysteries, and always keeps a little Indiana Jones inside her heart.

Also by Greta Gilbert

Mastered by Her SlaveEnslaved by the Desert TraderThe Spaniard’s Innocent Maiden

Discover more at millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk).

In Thrall to the Enemy Commander

Greta Gilbert

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

ISBN: 978-1-474-07358-5

IN THRALL TO THE ENEMY COMMANDER

© 2018 Greta Gilbert

Published in Great Britain 2018

by Mills & Boon, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street, London, SE1 9GF

All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. This edition is published by arrangement with Harlequin Books S.A.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, locations and incidents are purely fictional and bear no relationship to any real life individuals, living or dead, or to any actual places, business establishments, locations, events or incidents. Any resemblance is entirely coincidental.

By payment of the required fees, you are granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right and licence to download and install this e-book on your personal computer, tablet computer, smart phone or other electronic reading device only (each a “Licensed Device”) and to access, display and read the text of this e-book on-screen on your Licensed Device. Except to the extent any of these acts shall be permitted pursuant to any mandatory provision of applicable law but no further, no part of this e-book or its text or images may be reproduced, transmitted, distributed, translated, converted or adapted for use on another file format, communicated to the public, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of publisher.

® and ™ are trademarks owned and used by the trademark owner and/or its licensee. Trademarks marked with ® are registered with the United Kingdom Patent Office and/or the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market and in other countries.

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

For my dad: friend, mentor, sparring partner, fearless leader, fellow dreamer, guiding genius, benefactor, my superhero

Contents

Cover (#u524ff75f-7a32-56ab-9a77-d315510cc97c)

Back Cover Text (#u00916421-270f-5484-bf9a-7479952399e3)

About the Author (#u9898ee44-e98d-5f7f-a84f-f7b7f9c81ca6)

Booklist (#uf06cf3e9-ebd2-542b-8359-ec86c2c77695)

Title Page (#u5bd20567-523d-5bd3-a90a-2b24abd2e40b)

Copyright (#ue73b06fe-0b1e-53fb-9676-c133a349e37f)

Dedication (#u49731f1f-5da3-5bc6-a350-68cf169c6ebc)

Chapter One (#u86feb7b0-2df8-5c14-8250-71ae959827c6)

Chapter Two (#u365f4464-515e-5c38-bb4d-d6a394f337a2)

Chapter Three (#u702a374f-771c-5149-923e-38e359fe20d9)

Chapter Four (#u283bc3af-525f-548e-b66a-c81bfbb19df8)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#ue835f918-7c19-5b74-8cf2-2cf2453eb71e)

Alexandria, Egypt—48 BCE

She should have known better than to trust a Roman. She should have never listened to his honeyed speech, or considered his strange ideas, or dared to search his onyx eyes. Seth’s teeth—she was a fool. ‘Beware the heirs of Romulus and Remus,’ the High Priestess had always cautioned her, but the words had been but a riddle in her young ears. By the time she finally understood their meaning, it was too late. She was already in love and doomed to die.

She remembered the day she started down that terrible path. She was working at her master’s brew house in Alexandria, Egypt’s capital city. She had lived through one and twenty inundations by then and had been bound in slavery since the age of twelve. She had never tasted meat, or seen her face in a mirror, or touched the waters of the Big Green Sea, though the harbour was only streets away.

What she had done was toil. She awoke each day at dawn and worked without rest—stirring mash, cleaning pots, pouring beer—until the last of the brew house’s clients stumbled out on to the moon-drenched streets. Then she would curl up on a floor mat outside the door of her master’s quarters and welcome the oblivion of sleep.

That was Wen’s life—day after day, month after month, from akhet to peret to shemu. It was a small, thankless existence, redeemed only by a secret.

The secret was this: she knew Latin. She knew other things, too, but Latin was all that mattered. Few people in Alexandria spoke Latin. The official language of Alexandria was Greek, the language of Egypt’s Greek Pharaohs, though Egyptian and Hebrew were also widely spoken. But even Queen Cleopatra herself had sworn never to learn Latin, for it was the language of Rome—Egypt’s enemy. The tongue of thieves, she had famously called it.

As it happened, the brew house in which Wen laboured was frequented by Roman soldiers who spoke only Latin. They were known as the Gabiniani—tolerated in Alexandria because they had once helped restore the late Pharaoh to his throne.

But the Gabiniani were villains—rough, odious men who belched loudly, drank thirstily and sought their advantage in all things.

She knew their depravity intimately, though she tried not to think of it. It was enough to admit that they were loathsome men and she was happy to keep her watchful eye upon them.

Thus she earned her bread as a kind of spy—an Egyptian slave serving Roman soldiers in the language of Plato. She pretended not to understand their Latin chatter and placidly filled their cups. But whenever one bragged about thieving beer or passing a false drachma for a real one, she would happily inform her master.

She had saved her master thousands of drachmae over the years in this manner and he was able to provide his family with a good life. It was for this reason, she believed, that he never used her body for pleasure, and always gave her milk with her grain. It was also why she knew he would never set her free. She began to see her life as a river, flowing slowly and inevitably towards the sea.

But the goddess who weaves the threads of fate had a different plan for Wen. One morning, a man entered the brew house wearing an unusual grin. He was as dark as a silty floodplain and handsome in an ageless way, as if he had been alive for a thousand years. She believed him to be Nubian, though his head was shaved like an Egyptian’s and he wore a long Greek chiton that whispered across the tiles as he walked. A bracelet of thick gold encircled his arm and a heavy coin purse hung from his waist belt.

A tax collector, she thought. She was certain the man had come to collect taxes on behalf of the young Pharaoh Ptolemy, who was seeking funds for his war against his sister-wife, Queen Cleopatra.

‘Please, sit,’ she invited the man. ‘Goblet or cup?’

He did not answer, but regarded her closely, first in the eyes, then quickly down the length of her body, lingering for a time on the scar that peeked out from beneath her tunic.

‘How long have you been enslaved?’ he asked.

‘Nine inundations, Master. Since the age of twelve.’

‘Then you are the same age as the exiled Queen.’ Wen glanced nervously around the empty brew house. It was dangerous to speak of Queen Cleopatra in Alexandria. Her husband-brother Ptolemy was currently preparing to attack her somewhere in the desert. ‘You have a regal air about you,’ the man continued jestingly. ‘Are you sure you are not a queen yourself?’

‘I am as far from a queen as a woman can get, Master.’

‘That is not true. The roles and riches of this life are but—oh, how does that old saying go?’

‘The roles and riches of this life are but illusions,’ Wen said. ‘They matter not.’ It was a saying the High Priestess of Hathor had often repeated to her, though Wen had not heard it since she was a child.

The man’s face split with a grin. ‘Will you take me to your master?’

‘My master is away,’ Wen lied, as he had instructed her to do on such occasions. He despised tax collectors and would surely beat Wen if she let this man through to him.

But in that instant, her master emerged from his quarters and heralded the stranger, and soon the two men had disappeared into his office. When they re-emerged, she noticed that the coin purse no longer dangled at the man’s waist.

‘Serve this honourable traveller what he requests,’ her master told her, a rare smile beguiling his face, ‘and do whatever he asks. He has paid in full.’

Do whatever he asks? She felt her ka—her sacred soul—begin to wither. Her master was not a kind man, but she had always believed him to be decent. It appeared that decency had been only in her mind, for he had apparently sold Wen’s body for his own profit.

I could just run, she thought. I could dash out the doorway and on to the streets.

But the streets were more dangerous than ever. A Roman general had lately landed in Alexandria—a man they called Caesar—and was conducting diplomatic meetings with Pharaoh Ptolemy in the Royal Quarter. The General travelled with a legion of soldiers fresh from battle. They wandered Alexandria’s streets in search of diversions. If Wen were not captured by slave catchers, then surely she would be captured by one of Caesar’s soldiers seeking female company.

‘What do you ask of me, then?’ Wen whispered, speaking her words to the floor. She studied its cracked tiles, as if she might somehow mend the rifts in them.

But the man said nothing, nor did he attempt to lead her away. Instead, his stretched out his arms and held his hands open. ‘You need not fear me,’ he said in Egyptian, her native tongue. ‘I am not here to take, but to give.’

Then, as if by magic, a large coin appeared between his fingers. He toyed with it for several moments, then tossed it in her direction. Her heart beat with excitement when she perceived its formidable weight. But when she squinted to determine its worth, she saw that it was stamped with an image of the exiled Queen.

‘I am afraid that I cannot accept this generous gift,’ she said carefully in Greek. ‘Coins like this one have been forbidden by Pharaoh Ptolemy since Queen Cleopatra was exiled.’

‘Then you view Cleopatra as the rightful ruler of Egypt?’

Wen felt her jaw tense. It was a question too dangerous to answer. Cleopatra had been the first in her family of Greek Pharaohs to ever learn the Egyptian language and the first of her line to have worshipped the sacred bulls. When the River had failed to rise, Cleopatra had devalued the currency to purchase grain for the starving peasants and had saved thousands of lives. In only two years since she had assumed the throne, the young Queen had shown a reverence and love for Egypt unheard of in her line of Pharaohs.

Of course Wen viewed Cleopatra as the rightful ruler of Egypt. But she would certainly never admit it to a stranger, especially in the heart of pro-Ptolemy Alexandria. ‘No, ah, not at all,’ she continued in Greek.

‘You are a terrible liar, my dear,’ the man said in Egyptian, ‘though I sense much boldness in you.’ He flashed another toothy grin. ‘A cat with the heart of a lioness.’

‘What?’

‘I am Sol,’ he said, sketching a bow.

‘I am—’

‘Wen-Nefer,’ he interrupted. ‘I already know your name, Mistress Wen, and much else about you, though I admit that you are more beautiful than I had anticipated.’

Wen-Nefer. That was her name, though her master never used it. Nor did the clients of the brew house. They preferred you there, or girl. It had been so long since she had heard her own name aloud that she had nearly forgotten it.

‘I suppose you cannot read,’ said Sol, producing a scroll from beneath his belt, ‘so I will tell you that this scroll attests to your conscription by Cleopatra Thea Philopator the Seventh, Lady of the Two Lands, Rightful Queen of Egypt.’

His words became muffled—replaced by the loud beat of her heart inside her ears. He traced his finger down rows of angular Greek script and pointed to a waxen stamp. It depicted the same queenly cartouche that Wen had observed on the coin.

‘Your master has been paid,’ Sol continued, ‘and has released you to me. I have been instructed to escort you directly to Queen Cleopatra’s camp near Pelousion. Our driver awaits us outside.’

He was halfway through the open doorway when he turned to regard her motionless figure. ‘I see,’ he said with a sigh. ‘I must have been mistaken about you. It appears that you support Ptolemy’s claim to the Horus Throne.’

‘What? No!’

‘Then why do you not follow me?’

‘I...’ She paused. Her thoughts would not arrange themselves. How could she trust this strange man when his errand stretched the bounds of reason? ‘Forgive me, but I must know, why would the Queen want...me?’

‘It is my understanding that you have a special skill.’

Skill? She searched her mind. Beyond pouring beers and mixing brews, she had only one skill. ‘Do you refer to my ability to speak Latin?’

‘It must be that,’ said Sol, ‘though the Queen did mention something about your holy birth. Does that mean anything to you?’

‘I am a child of the Temple of Hathor.’

‘Ah! A child of the gods—it is no wonder the Queen summons you.’

Wen stood in confounded silence. Up until that moment, she had perceived herself unfortunate in her birth.

‘I assure you that I mean you no harm,’ said Sol. ‘But neither do I have time to waste. You may come with me now or remain here for the rest of your days. It is your choice. Only choose.’

Wen turned the coin over in her hands. She studied the profile that had been etched into its golden metal. It was a woman’s profile to be sure—a woman who, until only a year before, had ably ruled the oldest, most powerful kingdom in the world. She was a woman who had never known her own mother, had been neglected by her father and was hated by her husband-brother, who had lately put a price on her head.

If Sol was telling the truth, he would be leading Wen into mortal danger. Cleopatra was a woman surrounded by dangerous men, fighting to survive and likely to perish.

‘Well?’ asked Sol. ‘Are you coming or not?’

* * *

The carriage was of modest size, but to Wen it seemed a great chariot. They raced past the grand colonnades of Canopus Street with such speed that the pedestrians paused to observe them, staring out from beneath the green shade cloths.

Wen’s heart hummed. How bold she felt sitting on the bench with Sol—how wholly unlike herself. She undid her braid and let her hair fly behind her like a tattered flag.

Soon they had boarded a barge and were sailing upriver with the wind at their backs. Wen gazed out at the verdant marshlands as long-forgotten memories flooded in.

As a child, Wen had often travelled the River as part of the holy entourage of the High Priestess of Hathor.

It had been a great honor to travel with the High Priestess. As the goddess Hathor’s representative on earth, the Priestess was required to attend ceremonies from Alexandria to Thebes. She would always select from among the children of the temple to journey with her, for she loved them as her own.

There were dozens of children to choose from and more every year. They were conceived during the Festival of Drunkenness, when high-born men were allowed to couple with the priestesses of Hathor and experience the divine. Any children that resulted from their holy act belonged to the temple, their paternity unknown, their maternity unimportant.

For each of her journeys, the High Priestess chose a different set of temple children to accompany her, but she never failed to include Wen. While they sailed, she would invite Wen beneath her gauze-covered canopy and instruct her in the invisible arts.

She called the lessons ‘reading lessons’, though they had nothing to do with texts. They were lessons on how to read people—how to look into a man’s eyes and discover his thoughts.

She taught Wen how to spot flattery, how to uncover a lie and how to use the art of rhetoric to pull the truth from a man’s heart. She told Wen wondrous tales—the Pieces of Osiris, she called them, for they were words gathered together to teach Wen lessons.

‘You have the gift,’ the High Priestess told Wen one day as they floated towards Memphis. She stared into the eyes of her golden-cobra bracelet as if consulting it, then gave a solemn nod. ‘When you are ready, I will take you to meet the Pharaohs and we will find a place for you at the Alexandrian court. You will become a royal advisor, just as I have been.’

But that day never came.

Wen gazed at the silken water. So much had changed since then, though the River itself seemed unaltered. They skirted around shadowy marshes thick with lotus blooms, and floated past big-shouldered farmers who laboured in the deepening dusk.

Sol studied Wen with amusement as she gaped at the sights. ‘You watch with the eyes of a child,’ he mused, ‘though a child you are not.’ He glanced at her scar, which she had allowed to become exposed.

‘It is a battle scar,’ she offered, quickly pulling her leg beneath her skirt.

‘And did you win the battle?’

‘I am here, am I not?’

They travelled relentlessly into the night, moving from the gentle current of the river to the jarring bumps of unseen roads. Wen willed herself awake, fearful she might close her eyes and discover that the journey had been nothing but a dream.

She must have finally slept, however, for by the time she opened her eyes it was evening again and the souls of dead Pharaohs had already begun to salt the sky. Wen sat up and smelled the air. It was thick and briny, and she knew the sea was near.

They descended into a wide, flat plain where thousands of men loitered amidst a collection of tents. Sol explained that the men were soldiers—Syrian, Nabataean and Egyptian mercenaries who had been hired by Queen Cleopatra with what remained of her wealth. They were her only chance against her husband-brother’s much larger army, which was stationed in the nearby town of Pelousion, preparing to strike.

They came to a halt beside a large cowhide tent, and Sol leaped to the ground. ‘We have arrived. This is where we must part.’

‘Arrived where?’ asked Wen, taking his hand and jumping down beside him.

He flashed her an enigmatic grin, then motioned to the tent. ‘Go inside and wait. The Queen’s attendants will find you when her council concludes. No matter what happens, you must never address the Queen directly. You must wait until she speaks to you. Now go.’

‘You are not going to accompany me?’

He laughed. ‘The fate of Egypt will be decided in that tent.’

‘Do you not wish to learn it?’

‘The less I know, the better.’

‘I do not understand.’

He shook his head. ‘I think you do understand. You only pretend not to.’

He does not wish to be implicated in what is being decided, Wen thought. ‘Sol is not your real name, is it?’ she asked.

‘No, it is not,’ he said, smiling like a jackal. ‘Good for you.’ He bent and kissed her hand. ‘It has been an honour, Wen-Nefer. Perhaps we shall meet again some day.’ He gave a deep bow, then jumped back into the carriage.

‘Wait! You cannot just leave me here!’ she yelled, but he was already rolling away.

Chapter Two (#ue835f918-7c19-5b74-8cf2-2cf2453eb71e)

He might not have seen her at all: the colour of her shabby tunic matched the colour of the sand and her hair was so tangled and dusty it resembled a tumbleweed. But the group of guards escorting him to the Queen’s tent had grown larger as they passed through the camp, cramping his stride, and slowly he’d made his way to the edge of the entourage. As he passed by her, his thigh brushed her hand.

A shiver rippled across his skin. He wondered when he had last felt the touch of a woman. In Gaul, perhaps. Troupes of harlots always followed Caesar’s legions and, as commander of Caesar’s Sixth, Titus was allowed his choice from among them.

Not that he was particular. Women were mostly alike, he had found. Their minds were usually empty, but their bodies were soft and yielding, and they could provide a special kind of comfort after a day of taking lives.

Or at least—they had once provided him with such comfort. Now, after so many years of leading men to their deaths, even a woman’s soft touch had ceased to console him.

The woman drew her hand away, keeping her gaze upon the ground. She was obviously a slave, but she was also quite obviously a woman—a woman living in a desert military camp where women were as rare as trees. He wondered which commander she would be keeping warm tonight.

He had a sudden desire that it might be him.

There was no chance of that, however. As Caesar’s messengers, Titus and his young guard, Clodius, were under orders to deliver Caesar’s message to Queen Cleopatra, then return to Alexandria immediately. It was dangerous for Romans in Egypt, especially Roman soldiers. They were viewed as conquerors and pillagers, and were unwelcome in military camps such as these, along with most everywhere else.

As if to underscore that point, the guard nearest Titus scowled, then nudged Titus back towards the middle of the escort. There, Titus’s own guard, Clodius, marched obediently, his nerves as apparent as the sweat stains on his toga.

As was custom for sensitive missions such as these, Titus and Clodius had switched places. Clodius was playing the role of Titus the commander and Titus the role of Clodius, his faithful guard. This way, if Cleopatra chose to keep one of them for ransom, she would keep Clodius, whom she would erroneously believe to be the higher-ranking man, leaving Titus to return to Caesar.

‘Hello, there, my little honey cake,’ said a guard somewhere behind him. Something in Titus tensed and he turned to see one of the guards standing before the woman, pushing the hair out of her eyes.

She was not moving—she hardly even looked to be breathing—and was studying the ground with an intensity that belied her fear. Clearly she was not offering her services to the man, or any other. Titus almost lunged towards the man, but he was suddenly ushered into the tent and directed to a place at its perimeter. The offending guard entered soon after him and Titus breathed a sigh of relief, though he puzzled over the reason for it.

He tried to put the woman out of his mind as his eyes adjusted to the low light. In addition to the guards, there were several robed advisors spread about the small space, along with a dozen military commanders and men of rank. They stood around a large wooden throne where a pretty young woman sat with her hands in her lap.

Queen Cleopatra, he thought. Titus watched as Clodius dropped to his knees before the exiled Pharaoh in the customary obeisance. ‘Pharaoh Cleopatra Philopator the Seventh, Rightful Queen of Egypt,’ announced one of the guards.

To Titus’s mind, there was nothing Egyptian about her. She wore her hair in a Macedonian-style bun and donned a traditional Greek chiton with little to distinguish it from any other. She was surprisingly spare in her adornments and quite small of stature, especially compared to the large cedar throne in which she sat.

Still, she held her head high and appeared fiercely composed. It was an admirable quality, given that she was a woman. In Cleopatra’s case, it was particularly admirable, for her husband-brother Ptolemy had made no secret of his determination to cut off her head.

‘Whom do you bring me, Guard Captain?’ asked the Queen. ‘Why do you interrupt my war council?’

‘Two messengers, my Queen,’ said the head guard. ‘They come from Alexandria. They bring an urgent message to you from General Julius Caesar.’

The Queen exchanged glances with two women standing on one side of her throne. The taller of the two bent and whispered something into Cleopatra’s ear. The Queen nodded gravely.

Cleopatra was known as a goodly queen—one of those rare monarchs who actually cared about the people she ruled. Before her exile, it was said that she had done more than any of her predecessors to ease the lives of the peasants and to honour their ancient traditions.

Now that Titus finally beheld her, he believed that that her goodness was real. Her face exuded kindness, but also an intelligence that seemed unusual for one of her sex. She smiled placidly, but her eyes danced about the tent, never resting.

Still, Titus was careful not to venerate her. She was a woman, after all, and naturally inferior to the men who surrounded her. But even if she were a man, he would not make the mistake of supporting her rule. He knew the dangers of monarchs. One would spread peace and justice, then the next would spread war and misery. Kings and queens—or pharaohs, as they called themselves here in Egypt—were as fickle as their blessed gods and they could never be trusted.

There was a better way, or so Titus believed. It was a vast, complex blanket, woven by all citizens, that protected from the caprices of kings. They had been practising it in Rome for almost five hundred years and Titus understood it well, for his own ancestors had helped weave its threads.

Res publica.

Though now that glorious blanket was in danger of unravelling. When Caesar had crossed the Rubicon with his Thirteenth Legion, he had led the Republic down a dangerous path. Generals were not allowed to bring their armies into Rome. Nor were they allowed to become dictators for life, yet that was exactly what the Roman Senate was contemplating, for Caesar had bribed most of its members. There were only a few good men left in the government of Rome who remembered the dangers of monarchs.

Titus was one of them. He was one of the Boni—the Good Men—and also their most powerful spy. His job was to watch Caesar closely and, if necessary, to prevent the great General from making himself into a king.

And now that Caesar had defeated his rival Pompey, there were no more armies standing in his way. What better way to begin his rule than by occupying Egypt, the richest kingdom in the world, and turn its warring monarchs into tributary clients?

Or perhaps just murder them instead.

Titus could not guess General Caesar’s intentions, but he feared for the young Queen sitting before him now. Much like the woman he had seen outside the tent, she appeared to have no idea of the danger she was in, or how very helpless she was.

* * *

It was growing darker outside the tent. Wen had been ordered to wait inside, but could not gather the courage to enter. She placed her ear between the folds of the tent and listened.

‘Caesar means to conquer Egypt—the Queen cannot trust him.’

‘The Queen must trust him!’

‘He will take Egypt by force.’

‘The Roman Senate would never allow it.’

‘The Roman Senate does not matter any more!’

The clashing voices rose to a crescendo, then a woman’s voice sang out above them all. ‘Peace, now, friends,’ she said. ‘There are many ways to be bold.’

Wen drew a breath, then slipped into the shadows.

She could see very little at first. The torches and braziers were clustered at the centre of the room, illuminating a handful of nobles gathered around a wide wooden throne. On its pillowed seat sat a slight, dark-eyed woman dressed in a simple white tunic and mantle, and wearing the ivory-silk headband of royalty.

Cleopatra Philopator, thought Wen. The rightful Queen of Egypt.

The Queen wore no eye colour, no black kohl, and her lips displayed only the faintest orange tinge. Her jewellery consisted of two simple white pearls, which dangled from her ears on golden hooks.

To an Egyptian eye, she was sinfully unadorned, yet she radiated beauty and intelligence. She motioned gracefully to the figure of a man kneeling before her on the carpet. ‘Good counsellors,’ she sang out, ‘before we disagree about what Caesar’s messenger has to say, let us first allow him to say it.’

Laughter split the air, morphing into more discussion, all of which the Queen summarily ignored. ‘Rise, Messenger,’ she said, ‘and tell us your name.’

‘I am, ah, Titus Tillius Fortis,’ the young man said, rising to his feet, ‘son of Lucius Tillius Cimber.’ The room quieted as the counsellors observed the young messenger. He wore a diplomat’s toga virilis, though he appeared uncertain of how to position its arm folds.

‘The name is familiar,’ said the Queen. ‘Is your father not a Roman Senator?’

‘He is, Queen Cleopatra.’

‘I believe I met him many years ago. I was in Rome with my own father, begging the Senate to end their designs on our great kingdom.’

The Roman appeared at a loss for words. There was a long silence, which Cleopatra carefully filled. ‘Your father said that one of his sons served in Caesar’s Sixth.’

‘That is I, Goddess,’ the man said, taking the prompt. ‘I command that legion now. I am their legate, though I appear before you in a messenger’s robes.’

‘Caesar sends his highest-ranking officer to deliver his message?’ Cleopatra gazed out at the crowded sea of advisors. ‘That is promising, is it not, Counsellors?’

Someone shouted, ‘Is he not very young to command a legion?’ There were several grunts of assent and the Queen looked doubtfully at Titus.

‘I have only recently been promoted,’ Titus said. ‘I took the place of General Maximus Severus, who died defeating Pompey at Pharsalus.’

The Queen gave a crisp nod. ‘You may rise, young Titus,’ she said. ‘This council will hear your message.’

Titus demonstrated the seal on his scroll to a nearby scribe, who gave an approving nod. The young commander broke the wax and cleared his voice.

‘Before you begin,’ interrupted the Queen, ‘will you not also introduce your companion?’

Titus paused.

‘The one who lurks at the edge of the tent there,’ said the Queen, pointing to the very shadows in which Wen hid.

‘My Queen?’ asked Titus.

Wen prepared to step forward, certain that the Queen had noticed her.

‘Do not play the fool, Titus,’ said the Queen, craning her neck in Wen’s direction. ‘He is as big as a Theban bull.’

There was a sudden movement near Wen and a towering figure stepped out of the shadows beside her.

‘Ah, you refer to my guard,’ said Titus. ‘Apologies, Queen. That is, ah, Clodius.’

Wen’s heart skipped with the realisation that a Roman soldier had been standing beside her all the while, as quiet as a kheft. ‘He accompanied me from Alexandria for my protection,’ Titus continued. ‘He is one of our legion’s most decorated soldiers.’

Wen sank farther into the shadows as the Roman guard made his way through the crowd. He wore no sleeves and his chainmail cuirass fit tightly around his sprawling chest, as if at any moment he might burst from it. The red kilt that extended beneath his steely shell was too short for him, exposing most of his well-muscled legs. He held a helmet against his waist and walked in measured strides that seemed to radiate discipline. Wen wondered how she had not noticed him.

‘You may stop where you are, Clodius,’ said Cleopatra, holding up her hand as her own guards gripped their swords.

The towering Roman turned to his young compatriot in apparent confusion.

‘You heard her, Comm—ah—Clodius,’ he said in a rough soldier’s Latin.

The guard dropped to his knee and bowed. The torches flashed on the muscled contours of his arms, giving Wen a chill. She feared such arms. They were Roman arms, designed to destroy lives.

‘Apologies, Queen Cleopatra,’ said Titus. ‘My guard does not speak the Greek tongue.’

‘Of course he does not,’ said Cleopatra, regarding the man’s arms as Wen had done, ‘for his realm is obviously the battlefield, not the halls of learning.’

‘Shall I dismiss him?’

A buxom young woman standing beside the Queen bent and whispered something into her ear. ‘Do not fear, dear Charmion,’ Cleopatra answered aloud. ‘He will not harm me. As you know, the Romans value glory over all else. There would be no glory in assassinating a queen on the eve of her military defeat now, would there?’

‘You heard her, ah—Clodius,’ said Titus in Latin. ‘Please, return to your post.’

There was something curious about the way Titus spoke to Clodius. Something in the tone of his voice, perhaps, or in his choice of words. The High Priestess would have sensed it right away and known exactly what was amiss. But Wen could not identify it and was soon distracted by the sight of Clodius himself striding back towards the shadows in which she stood.

Time slowed as he took his position beside her and she perceived the long exhale of his breaths. She braved a glance at him, but his brow was too heavy to see his eyes and the rest of his expression was a mask of shadowy stone. ‘General Gaius Julius Caesar,’ Titus began, reading from his scroll, ‘Protector of the Roman Republic, Defeater of Pompey the Great, Conqueror of Gaul...’

The Queen held up her hand. ‘We do not have time for scrolls, good Titus. Please speak Caesar’s message in your own words.’

The Roman looked up. ‘My Goddess?’

‘What does General Caesar ask of me?’

Titus cast his gaze about the room, as if searching for Clodius. ‘Well?’ asked Cleopatra.

‘Ah, General Caesar begs an audience with Your Divine Person,’ he said at last.

Cleopatra’s expression betrayed no sentiment, yet Wen sensed her careful choice of words. ‘What does Caesar hope to gain by summoning me? He allies himself with my husband-brother, Ptolemy, after all, and occupies our very palaces.’

‘He has made no alliance with Ptolemy,’ answered Titus. ‘He wishes to reunite the Lord and Lady of the Two Lands.’

There was a collective gasp and then the room went quiet. ‘Reunite me with Ptolemy? For what motive?’

‘Your Divinity...ah...to please the gods.’

‘He wishes to collect the money my late father owed him,’ Cleopatra said to a flood of laughter.

A bald man in a green robe bent to whisper something into Cleopatra’s ear. The Queen gave a resigned nod, then set her flickering gaze upon the crowd.

‘This priest of Osiris believes that Caesar and my husband-brother conspire to kill me. Who here agrees that Caesar summons me to my death?’

A chorus of voices sang out in agreement, and Wen thought to herself how mistaken they all were.

‘You there,’ the Queen called out. ‘Why do you shake your head in dissent?’

The room went silent. Wen looked around, but she could not discern which of the men had been addressed. ‘Do you disagree with the Osiris priest and these other distinguished men?’ asked the Queen. She was staring directly at Wen.

She had addressed Wen.

Wen felt heat rising in her cheeks. ‘Ah, yes, My Queen,’ she sputtered.

‘Come forward,’ said Cleopatra.

Wen willed her quaking legs through the crowd of advisors, imagining what her head would look like on a spike. When she arrived before the Living Goddess and kneeled, her hands were trembling like a thief’s.

‘You may rise,’ said Cleopatra. ‘Who are you and by whose permission do you appear in my presence?’

‘This is Wen of Alexandria,’ offered an ancient man with long white hair. ‘She is the woman you requested, Goddess. Egyptian by birth, but speaks a commoners’ Latin.’

‘Ah, yes, the...translator,’ Cleopatra said. ‘Thank you, Mardion.’ Cleopatra studied Wen with interest and Wen became painfully aware of her bare feet on the Queen’s fine Persian carpet. ‘Tell me, Translator, why would Caesar not kill me if I go to him now?’

Wen felt every eye in the room upon her and her courage flickered with the braziers.

‘Speak,’ Cleopatra commanded. ‘The fate of Egypt is at stake!’

‘I have heard that Caesar has a taste for h-high-born women,’ Wen blurted, instantly aware of the veiled insult she had made.

But the Queen only nodded. ‘I have heard this rumour as well. Go on.’

‘Th-the Gabiniani of Alexandria say that he has conquered as many women as he has kingdoms. The wives of Crassus and Pompey—even Lollia, the wife of the Gabiniani’s own beloved General. I do not think Caesar will kill you, Goddess. Instead he will seek to conquer you as he does all women of power and beauty. In order to prove his worth.’

Cleopatra wore a puzzled expression. She narrowed her eyes. ‘Do you support my brother Ptolemy’s claim to the Horus Throne?’

‘No, my Goddess!’

‘Then why do you mingle with the Gabiniani?’

‘They frequent the brew house where I toil. Toiled. In Alexandria.’

‘In other words, you were bound to serve Roman soldiers and speak to them in their tongue?’

‘I did not speak, my Queen. I only listened.’

‘An Egyptian woman fluent in the Latin of Rome, yet wise enough not to use it,’ the Queen said. She sat back in her throne. ‘You are a rare coin, Wen of Alexandria.’

Wen exhaled, feeling that she had passed some sort of test.

A beautiful woman with a halo of black hair bent and whispered something in the Queen’s ear. The Queen nodded. ‘Speak your question, Iras.’

The woman stepped forward and fixed her thick-lidded gaze on Wen. ‘You say that Roman soldiers value conquest above all else. How come you by such knowledge?’

‘The Roman men I serve often brag of it, Mistress. They seek to conquer foreign women as a kind of sport. I know this to be true because I—’ she began, but her mind filled with a hot fog and she could not continue.

The Queen and Iras exchanged a knowing glance. ‘You do not love Roman soldiers, I presume?’ asked Cleopatra.

‘You presume correctly, Goddess.’

‘What is your name again, Translator?’

‘Wen-Nefer, my Queen. Wen.’

‘Wen, do you believe I can conquer this Caesar of Rome?’

‘I do.’

‘Tell me how you would have it done.’

‘You must make him believe that he has conquered you.’

‘And you know this to be the best way possible, based on your knowledge of Roman soldiers?’

‘Yes, and because you are cleverer than he.’

‘You seek to flatter me?’

‘I seek... I seek only to avow that Egypt is cleverer than Rome. And you are Egypt.’

The Queen sat still for several long moments. She motioned to her advisor Mardion and whispered something in his ear. He studied Wen closely, then whispered something back.

She glanced at her two handmaids, both of whom gave solemn nods. ‘It is decided,’ she said at last. ‘I shall heed Caesar’s call. I shall travel to Alexandria in secret and meet him in my palace. I shall trick him into conquering me and thus shall conquer him. And you, Wen, will come with me.’

* * *

It trespassed the boundaries of reason. A Queen of Egypt relying on the political advice of a simple slave woman? Madness. Either the witty Queen Cleopatra had lost her wits, or the woman who called herself Wen was not who she appeared to be.

Who was she, then? The question gnawed at him. He studied her from his position at the tent’s periphery, hoping to discover a clue.

She was a disaster of a woman, in truth. She stood rigid before the Queen in that sack of a dress, staring at her grubby toes. Her hair was a tangle of dirty locks that cascaded over her bronze shoulders in wild black tongues. He could not discern her shape, but her bare arms displayed the unfeminine musculature of a hard-toiling slave. He might have pitied her, if he were not so totally perplexed.

How could an Egyptian slave woman have such profound insights into Rome’s greatest General? Her assessment of Caesar had been brilliant—something a military officer or political advisor might have given. It seemed impossible that she could have gleaned such knowledge by simply pouring beer for Roman soldiers.

Perhaps she does more than pour beer, he thought. Perhaps she served as a hetaira, a learned prostitute for high-born men. He watched how she held herself, searching for clues. Impossible. Her posture alone suggested a kind of defeat and her chapped, calloused hands told the story of a life of washing dishes and scrubbing floors.

Nay, she was no hetaira. She was about as far from such a role as a woman could get. He scanned her body and noticed the pink stain of a scar rising up from the small of her leg. He followed the scar’s intriguing path, wondering where it led, but it quickly disappeared beneath the ragged hem of her tunic.

She was an enigma: the only thing about this tedious war council that he did not understand.

Yet she already seemed to understand him, or at least to suspect his ruse.

He had given her no reason to suspect him of anything. He had played the role of soldier flawlessly, had approached the Queen with a single-minded militancy and correctly feigned ignorance of her royal Greek. If there had been a weakness in the performance, it had been in the fumbling commands of his guard Clodius, though none in the Queen’s audience seemed to have noticed.

None except—what had she called herself?

Wen.

She seemed to be the only one to suspect anything, for as he, the real Titus, had returned to the shadows beside her, she had flashed him a suspicious glance—one that had rattled him to his bones. Even if she did not know that he and his guard had switched places, she obviously suspected something. And if she could tease out that secret so easily, what other, more serious secrets might she be capable of discovering?

He shook off a shiver and directed his attention to the discussion at hand. The advisors were debating how the Queen might travel to Alexandria without detection by Ptolemy’s spies.

‘The Queen must make the journey by the River,’ one of the priests was saying. ‘She can take the Pelusiac branch of the Delta up to Memphis, then back down the Canopic branch to Alexandria.’

‘That would take five days or more,’ said one advisor.

‘And the river boatmen gossip like wives,’ said another. ‘She would be discovered and Ptolemy would send out his assassins.’

‘To go by land would also be unwise,’ called another. ‘Ptolemy has offered a reward in gold for the Queen’s capture. There will be men in every village looking to profit from her head.’

‘Then she must go by sea!’ someone called. ‘It is the only way.’

‘Ptah’s foot!’ barked the advisor Mardion. He wagged a knobby finger at them all. ‘Her vessel would be seized the moment it entered the Great Harbour.’

The room erupted in another spate of discussion—one to which even young Clodius did not appear immune. Wen appeared to be the only one in the room not engaged in the debate. She remained eerily still and silent against the din.

At length, Cleopatra stood and raised her hands. ‘Gentlemen, it is late. Decisions made in the hours of Seth are never good ones. Tomorrow afternoon we shall reconvene and make our decision.’

There was a collective sigh of relief as the council turned to await the Queen’s exit. Titus felt himself relax. They had succeeded in their ruse. None seemed to guess that the two Romans had switched places—that he, the elder and the stronger, was the true son of a senator and the real commander of Caesar’s Sixth.

None except, possibly, Wen. She remained still and unmoving as the Queen’s entourage of women bustled about their beloved monarch. She had become invisible, it seemed, to everyone but him.

Chapter Three (#ue835f918-7c19-5b74-8cf2-2cf2453eb71e)

Wen kept her head bowed as the war council concluded and the Queen and her entourage exited the tent. The advisors followed after, streaming out of the tent in a garrulous mass. Someone pushed Wen forward and she became swept up in the exodus.

She recalled Sol’s words—one of the Queen’s attendants will find you—and realised that she needed to get herself to a place where she could be found. Outside the tent, she headed towards the only torch she saw, then bumped squarely into a wall.

A human wall. Of muscle and bone.

The Roman guard.

His titanic figure bent over her, as if trying to make out the features of her face. ‘You,’ he breathed in Latin.

Her heart raced. She turned to retreat, but he took her by the arm. ‘Who are you?’

‘Who are you?’ she returned, yanking herself free. There was little light and they were surrounded by bodies. He encircled her in his arms, creating a cocoon of protection against the jostling crowd. Her head pressed against his chest.

Poon-poon. Poon-poon.

She had never heard such a sound.

Poon-poon. Poon-poon. Poon-poon.

It was the sound of his heart, she realised—loud enough to perceive, even through the hard metal of his chainmail, like a small but mighty drum.

Poon-poon. Poon-poon. Poon-poon. Poon-poon.

The night wind swirled around them.

‘Who are you?’ he whispered huskily. He brushed her tangled hair out of her eyes. ‘Who?’

She pushed against his embrace, testing his intentions. ‘Why does it matter?’

He slackened his hold, but did not release her. ‘I wish to know you better.’

Know me better? In her experience, the only thing Roman soldiers wanted to know was how she planned to serve them. Still, there was something unusual about this Roman soldier. When he had cleared the hair from her face, it was as if he had been handling fine lace.

‘Why do you wish to know me better?’ she asked.

‘I sense that you are not as you seem.’

‘Is anybody?’

He chuckled. ‘I supposed you have a point.’

The crowd had cleared. There was no longer any reason for him to be holding her, though he pulled her closer still, and she could feel the twin columns of his legs pressing against her own.

He uttered something resembling a sigh and she felt the upheaval of his stomach against hers. He moved his large hand down her back, forcing her hips closer and manoeuvring one of his legs between her thighs.

Her stomach turned over on itself and a strange thrill rippled across her skin. It occurred to her that she was straddling his massive leg as if it were a horse.

‘Curses,’ he groaned. He took a deep breath and buried his nose in her hair.

What was he doing? More importantly, why was she not stopping him?

‘Why do you feel so good?’ he asked with genuine surprise, moving his hands in tandem up her back.

She wanted to pull away from him, but she could not bring herself to do it. It was as if his body was having a private conversation with hers and cared not what her mind might think. He pressed his leg more firmly between hers, sending pangs of unfamiliar pleasure into her limbs.

He thrust his hips towards her and she felt the hardened thickness of his desire press against her stomach.

‘Enough!’ she gasped. She wrenched herself backwards, stumbling to keep her balance.

‘Apologies,’ he said. ‘I do not know what overcame me.’

‘I must go,’ she said, stepping backwards.

‘Answer my question.’

‘What question?’

‘Tell me who you are.’

‘I am nobody.’

‘You do not understand my meaning,’ said the Roman. ‘I am Clodius of the familia Livinius. My kin have lived in the same house in the Aventine neighbourhood of Rome for over three hundred years. My father was a soldier and so am I. A soldier and a son. That is who I am.’

‘Is that it?’

‘Do you doubt me?’

She held her tongue.

‘I am not a liar.’

She took one more step backwards. ‘I have not called you a liar.’

‘But you suspect that I am one.’

‘I suspect nothing.’

‘You cannot hide from me,’ he said. His voice grew in menace. ‘You have been trained in the art of suspicion and I want to know who trained you.’

Suddenly, it all became clear. She threatened him: that was the reason he had held her so close. He wished to gain some advantage over her, to redirect her doubt of his own dubious identity. He did not care for her or desire her at all.

‘I am nobody,’ said Wen, turning away in stealth. ‘I am a slave.’

She heard him take another step closer, but she had already tiptoed beyond his sights. She spied a large tent at the perimeter of camp and began to make her way towards it, glad she knew better than to trust a Roman.

* * *

‘They cannot stand the sight of us,’ Clodius observed. He and Titus were sitting together on the beach, watching a group of Egyptian soldiers launch a fishing boat into the sea.

‘Can you blame them? Cleopatra’s father owed Rome over four thousand talents. Our presence here is like the appearance of wolves at a picnic.’

‘So why were we commanded to come?’

Only I was commanded to come, thought Titus. He had been awoken by Cleopatra’s advisor Mardion in the middle of the night. The old man had told Titus to gather his belongings. He was to make haste to the beach, by orders of the Queen.

‘I believe I was meant to help those fishermen,’ said Titus.

‘It seems a little early for fishing, does it not?’

Titus gazed at the sky. The stars were fading, but the light of dawn had yet to arrive. A realization struck him.

‘That is not a fishing boat at all,’ Titus said. ‘That is the Queen’s ship, man. It is bound for Alexandria.’

‘But her route is not yet decided,’ said Clodius.

Titus studied the unassuming, double-oared boat, its two young oarsman rowing out past the waves. ‘I think Queen Cleopatra is cleverer than we thought. Look there.’

A jewelled hand was reaching around the curtains of the deck cabin, tugging them closed. Clodius gasped. ‘She is already aboard?’

‘I fear we will soon be parted, Clodius,’ said Titus urgently. ‘You must remember our ruse. You are the son of a Roman senator now. You must comport yourself with dignitas at all times.’

But Clodius was not listening. His attention had been captured by two elegantly dressed women who appeared at the far end of the beach.

The first walked with smooth grace, her limbs long, her hair a wide cascade of tight curls. Her beautiful dark skin shone like polished obsidian and her appealing slim figure was enhanced by the snug Egyptian tunic she wore. In her arms she carried a medium-sized chest that Titus guessed contained belongings of the Queen.

‘Venus’s rose,’ said Clodius.

‘I believe she is called Iras,’ said Titus. ‘She stood behind Cleopatra at the war council. I believe she is the Queen’s first handmaid.’

Next to Iras walked the woman the Queen had called Charmion, her Greekness evident in the wreath of flowers adorning her hair. She walked with an energetic bounce, exaggerating the sway of her lovely hips. Charmion, too, carried a small chest, but it was propped on her side, resulting in the favourable display of her abundant breasts.

‘Forget Venus—I should like to worship one of those two. Which do you choose, Commander?’

‘Remember your dignitas, Clodius. You must—’

‘But there is a third,’ Clodius interrupted. ‘Do you not see her?’

It was true. There was another woman walking half a pace behind the other two. She carried a chest that was of much greater size and apparent weight than the other women’s, though she was plainly the smallest of the three. Still, she appeared quite equal to her burden and she walked with an almost comical determination.

‘That is the Queen’s translator,’ Titus said. ‘Wen.’

‘She is not quite as grand as the first two, but pretty in her way,’ said Clodius.

Titus swallowed hard. To him, she was more than pretty, though he was unsure what it was about her that made him admire her so.

She had clearly bathed and oiled herself, and her skin shone bronze in the increasing light. Her long black hair had been braided, then pinned in a neat spiral around her head, revealing the alluring column of her neck.

But he had admired many such necks.

Perhaps it was her eyes. The already large, dark lamps had been made larger with the liberal application of kohl, giving her a feline quality that was compounded by her unnerving alertness. She made Titus’s blood run hot.

‘Well, which do you choose?’ asked Clodius. ‘Commander Titus?’

Titus cringed. ‘You must not address me as Commander Titus!’ He dropped his voice to a whisper. ‘You are Titus now, remember? You must play the part.’

What happened next was one of the strangest things Titus had ever seen. The handmaids hurried to join the men loading the shore boat. They placed their chests in the boat and removed their sandals. Then the whole group dropped to their knees in prayer.

‘What are they doing, Commander—I mean, ah, Clodius?’

‘I believe they are asking their sea god for his good will.’

‘The women are allowed to pray alongside the men?’

‘In Egypt it is so.’

Suddenly, Mardion and two guards appeared at the edge of the beach. They were towing a large sheep.

‘And what now?’ asked Clodius.

‘I believe they are going to sacrifice that sheep.’

‘Does that mean there will be mutton to eat?’

‘A son of a senator would never ask such a question.’

‘About mutton?’

Titus shook his head in vexation, grateful they were out of earshot of anyone else.

The sheep’s death was mercifully swift, though Mardion took his time studying the animal’s entrails. When his examination was complete, he took a bowl of the sheep’s blood and offered it to the waves. When he returned, he handed the empty bowl to Iras, and bowed to her.

‘Did I just see what I think I saw?’ asked Clodius.

‘An elder statesman bowing to a young woman—yes, you did.’

Clodius shook his head in vexation. ‘It is as if the women here are—’

‘Equal to the men. No, but they are certainly more equal than in Rome. Did I not warn you about Egypt’s backwardness?’

The strange ceremony was not yet over. The men and women gathered at the edge of the surf and, one by one, they dived into the waves, then emerged and headed back towards the fire.

‘Jove’s balls,’ said Clodius, staring at the saturated figures of Iras and Charmion. Their white garments had become transparent as a result of their watery inundation, revealing the dark round shadows of their pointed nipples. ‘Just look at those Venus mounts!’

‘Watch your language,’ Titus scolded. ‘And stop gawking. Dignitas!’

If Titus had been in his right mind, he might have explained that Egyptian tradition held unusual ideas about female nudity. Visible breasts were common in Egypt and an educated Roman nobleman knew better than to gape at them. Still, when he caught sight of Wen, Titus became culpable of the very behaviour he was trying to prevent.

Her long, dark tunic clung tightly to her flesh, leaving none of her soft curves undefined. It was as if his own body held a memory of those curves and he yearned to pull her against him once again.

Wen’s breasts were not as visible as the other women’s. The taut peaks of her nipples remained concealed by her tunic’s dark hue, but he was inspired to imagine them: succulent dark olives that begged to be tasted.

Curses on his wretched soul. He was trying to teach his young charge dignitas, yet he could not seem to peel his eyes away from the vision of some inconsequential slave woman drenched in seawater.

In his frustration, he reached for his guard’s arm and squeezed it. ‘You have listened to me, but you have not heard me, so let me put it plainly: if your true identity is discovered, you will likely suffer a flogging, or you may be dragged through the camp behind a chariot. Do you understand?’

‘Yes,’ Clodius replied absently.

‘Do you really understand?’ Titus repeated, yanking the young man to face him. ‘It is your life I am talking about.’

‘I understand.’

Titus released Clodius’s arm. Chastened, the young soldier remained silent for so long that Titus feared that he had hurt his pride. ‘The Egyptian,’ Titus said at length.

‘What?’

‘You asked me whom I choose—of the three handmaids. I choose the small Egyptian.’

A roguish grin returned to Clodius’s face. ‘Then you are as mad as I suspected.’

The sun peeked over the horizon and the three soaking maidens turned like sunflowers towards its warm rays while the men—the men!—butchered and cooked the sheep. Soon chunks of cooked mutton were being passed around on knives and everyone ate while Titus and Clodius looked on hungrily.

‘Mutton or maiden?’ asked Clodius with a smirk.

Titus’s stomach rumbled. ‘Certainly mutton,’ he said.

Clodius rolled his eyes. ‘I would starve for a week if only I could have just a single taste of maiden.’

‘If we stay any longer, I fear we will begin to howl like wolves,’ Titus said, stepping from the shade. ‘Let us depart.’

But it was too late. Mardion and his guards were already running up the beach towards them, their swords drawn. ‘What is happening?’ asked Clodius, reaching for his gladius sword. ‘Why do they attack?’

‘They do not attack, so do not fight back!’ whispered Titus. ‘We are at their mercy now. Remember the ruse.’

The guards seized Clodius’s arms and Mardion spoke. ‘Titus Tillius Fortis, son of Senator Lucius Tillius Cimber, you are now a royal hostage of Queen Cleopatra.’

Clodius froze. For the first time all morning, the young soldier appeared at a loss for words. ‘Your guard will accompany the Queen to Alexandria and guide her to Caesar,’ explained Mardion. ‘You will stay here at camp. As long as Cleopatra remains alive, so will you.’

‘Dignitas,’ Titus whispered, and the guards dragged Clodius away.

Titus drew a breath. It had not been the most graceful of partings, but they had managed to sustain their ruse. And it had been worth the effort, for the Queen and her advisors had taken Clodius, believing him to be Titus. As a result, the real Titus was now headed back to Alexandria—back to his post at General Caesar’s side. There, he could resume his command of the Sixth, as well as his other, more important work.

Relief washed over him as he followed Mardion towards the fire. When he finally looked up, he noticed that Wen was watching him, her large dark eyes as steady as stones. She shook her head slightly, as if in disapproval, then cocked her head at him like a kitten.

Did she suspect him of something? Impossible. He had done nothing to warrant her suspicion. And even if he had, she could not produce any proof of his deception.

Besides, she was just a woman, with a woman’s limitations of intellect. He had no reason to worry, though he admitted that in that moment he felt stripped naked by her gaze, as if she were the priest and he the sheep.

* * *

They set off at dawn across a glassy sea. Wen stood against the starboard rail, staring out at the vastness, but all she could think of was his crocodilian grin and the poon-poon-poon of his beating heart.

‘The water is beautiful in the morning, is it not?’ said Apollodorus, one of the rowers heaving backwards on the row bench.

‘A more beautiful sight I have never seen,’ said Wen, tossing the Sicilian a friendly grin.

She deliberately ignored the Roman, though he occupied the bench directly behind Apollodorus and his gaze seemed to follow her beneath his heavy lids. She did not appreciate his watching her, for it prevented her from watching him.

She peeked at him sidelong, pretending to watch a gull. He had removed his chainmail cuirass and as he pulled backwards on the oars his tunic hugged against the deep contours of his chest. She had never seen such a powerful man and he flexed his legs with a languid ease that was unnerving.

Restless, she strode behind the deckhouse to the stern, heralding the two rudder boys and pausing near the deckhouse window. Inside, the Queen and her handmaids dozed, snoring in rhythm with the rocking waves. Wen whispered a prayer to Hathor for their peace and safety and another prayer to Isis to give thanks.

Because of Queen Cleopatra, Wen would never again stare at the mud-brick walls and wonder what lay beyond them. Nor would she ever have to endure the stares of drunken Romans, or defend herself against violent lechers, or feel her life slipping away with each pour of beer. Never again—for the Queen had saved her.

In return, she vowed to save the Queen. Wen could not stand up to invading armies, of course, but she could protect Cleopatra from hidden plots and reckless advice. Wen had been trained in such matters, after all—by the High Priestess of Hathor herself. And she would use that training as best she could to support Cleopatra’s reign.

* * *

Wen stared out at the placid sea once again, hardly able to believe it was real. She had always known the sea was there—somewhere beyond the brew-house walls. It had been close enough to smell, to hear, yet never close enough to touch.

Once, when she was much younger, she had been determined to know the sea. She had begged her master for permission to visit the harbour, hoping to find her way beyond it. Just once in her life, she wanted to gaze out at the open ocean, to witness the tempestuous realm that the soldiers and sailors spoke of with such awe. To see what lay beyond.

Her master said he would consider her request and, as the months passed, she developed a plan. She would follow the shoreline promenade to Heptastadion Bridge, where she would cross to Pharos Island. There, she would make her way to the base of the Lighthouse, sneak past the toll taker and climb to the middle platform. Upon that high perch, she would gaze out at the endless sea and the meaning of her life would be revealed.

It was a beautiful dream, and Wen clung to it fiercely, even as the months passed, and then, slowly, the years. She reminded her master of the request several times, but he only nodded without hearing.

Then, one evening, a fight broke out in the brew house and, in the chaos, Wen was dragged to the rooftop where she struggled against a man twice her size. There were blows and blood, and a terrifying jump. As she wallowed unaided on the stony ground, she became fully aware of how little her dreams mattered. How little she mattered.

After her wounds had healed, her master finally granted her wish. ‘You may take a day of rest and visit the Lighthouse,’ he had told her. He had even given her money—a small round coin for the toll taker: an apology cast in bronze.

But it was too late. ‘Thank you, Master, but I would rather stay here,’ she had said, returning the coin to his wrinkled hand. She no longer wanted to visit the harbour, or the Lighthouse, or gaze out at the Big Green Sea. Such dreams were not for women like her.

Or so she had believed, until the Queen had saved her.

Wen returned to the stern and stared at Titus, daring him to meet her gaze. She resolved to do everything in her power to be worthy of the Queen’s kindness, even if it meant appointing herself as a royal spy. If Titus was a snake hiding in the grass, then Wen would be the hawk. She would not rest until she discovered his secret.

* * *

Titus was grateful for his post at the oars, for it gave his body purpose. His mind, unfortunately, was as restless as the sea.

He wanted her and it was a problem. She was not his to want. She was a slave, a bonded soul. Her body was the property of another—in this case the exiled Queen of Egypt.

In truth Titus pitied her, as he did all slaves. There were so many in Rome now. They represented almost a third of Rome’s population and their numbers grew with each military conquest. They were a tragic people, so stripped of their own will that they relinquished it entirely. Not since the time of Spartacus had slaves risen up and he doubted they would do it again. They were a passive, miserable lot, resigned to the injustice of their lives.

Titus pitied slave women: he did not desire them.

That is what he reminded himself as she strolled about the deck.

That afternoon, a wind came up, a strong northerly that allowed Titus and Apollodorus to rest their arms while the rudder boys hoisted the sails. Titus closed his eyes and tried to rest as their small ship began to make speed.

They made camp at the mouth of a small river that evening and enjoyed a simple meal of flatbread, dried fish and grapes. Apollodorus made a fire and soon they were staring into its flames.

Titus must have fallen asleep, for he awoke to the rhythm of Apollodorus’s snores. There was a softer sound, as well—the sound of women’s laughter.

‘I think he is quite handsome,’ whispered a voice that he recognised as Charmion’s. It was coming from directly behind him, as he lay on his side, his back to the flames. ‘Look at how his hair stands upon its ends. I would like to run my fingers through it.’

‘I, too, am partial to the Roman,’ whispered another woman.

Iras, he thought.

‘He is so very like a tree. I would like to climb his branches.’

‘I would like to wander the marshes with him,’ whispered Charmion. There was a conspiracy of laughter that made him wonder if ‘wander the marshes’ really meant exploring Egypt’s prodigious wetlands.

He was sure that it did not. These were women, after all—silly creatures who enjoyed gossiping and making mischief. He was not wholly against their kind, of course. He loved their soft, curvy bodies and found it enjoyable to give them pleasure, though his military career had afforded him little time for such pursuits.

In the camps of Britannia and Gaul he had learned everything he needed to know about women, for they would often visit him in his tent. Mostly they were working women—Roman and barbarian harlots who followed the legions to earn their bread. They never had much to say, though they were always happy to see Titus and seemed to enjoy the pleasures he offered. Still, he was careful not to flatter himself that they actually enjoyed his company and he always paid them well for theirs.

When he finally returned to Rome he quickly learned that not all women were like the harlots he patronised in the camps. High-born noblewomen were another breed entirely. They were boundless in their ambition—greedy and ruthless as any general. And as the highest-ranking bachelor in Caesar’s army, Titus was apparently a territory worth conquering. The mothers of Palatine Hill had made it their business to find Titus a good patrician wife and they presented their daughters to him in a never-ending series of banquets.

But the women were like shells—beautiful, alluring and disappointingly empty. Their desire for wealth and status ranged far beyond their intellect. They were easily bored and seemed unable to participate in even the most basic discussions of philosophy or politics. The women of Rome vexed him, and though he disagreed with Caesar’s bloody civil war, he was happy to be called away to duty.

‘We must be quiet,’ whispered Iras. ‘He is probably listening to us right now.’

‘I do not think he can understand us,’ said Charmion. ‘He does not speak Greek.’

‘Ah! I had forgotten,’ said Iras. ‘Do you think if I lay down beside him he would speak Latin into my ear?’

‘Senatus Populusque Romanus,’ mocked Charmion.

‘E pluribus unum,’ added Iras, snickering.

Women.

Still, these women of Egypt seemed a different breed. Unlike Roman women, they were allowed to study trades and conduct business, as if they were men’s equals. They could even divorce and inherit property—backwards notions if ever he had heard them. Indeed, it seemed that Egyptian women said and did whatever they wished, with no consideration for the men who were their natural superiors.

‘What say you, Wen?’ asked Iras. ‘Which of our two oarsmen do you choose?’

Titus held his breath.

‘Mistress?’ said Wen.

‘Do you also prefer the Roman?’

‘In truth, Mistress, I prefer Apollodorus,’ said Wen.

Titus could not believe his ears.

‘Really?’ said Iras, in surprised delight. ‘How interesting. Well, I suppose the Sicilian has his merits. His loyalty to the Queen is certainly apparent.’

‘Almost as apparent as his pot belly,’ Charmion giggled.

‘Shush yourself,’ snipped Iras. ‘But tell us, Wen, for what reason do you favour the Sicilian?’

Wen’s voice was barely audible. ‘He seems loyal to the Queen and his motives are clear.’

There was a pause, then both Charmion and Iras burst into laughter.

‘That is quite philosophical of you, Wen,’ said Charmion at last. ‘Are you sure you do not prefer a man who can throw boulders?’

Wen gave a polite laugh. ‘Loyalty is more important than strength.’

Something in the tone of her voice pricked at Titus’s mind. It was as if she were speaking to him indirectly, as if she were trying to send him a message.

As if she guessed that he was awake.

He slept little the rest of the night. What bothered him most was not that she did not trust him. He had grown accustomed to the idea of her suspicion, much as a gardener might grow accustomed to an unpicked weed. What he could not fathom was her preference for the Sicilian. Apollodorus was a loyal man, to be sure. Even Titus had heard of his efforts in recruiting Queen Cleopatra’s army of mercenaries.

But the man was obviously a glutton. He had breath like a stinking beetle and a stomach the size of a cow’s. How could she choose such a man? And why, more importantly, had she chosen him over Titus?

Chapter Four (#ue835f918-7c19-5b74-8cf2-2cf2453eb71e)

They departed before dawn the next morning. As Titus and Apollodorus found their rhythm at the oars, Wen appeared alone on the deck. She gazed out at the sea, her arms tight around her chest.

He could have said that his trouble began when his thigh grazed her arm, or moments after that instant, when she stood beside him at the Queen’s war council—though that would not have been entirely true. When she slipped into the shadows beside him, he had regarded her as a mere mouse, probably sent from the gossip-hungry soldiers to steal a bit of cheese.

He could have said that his trouble began when he held her against him, trying to protect her from the crowd, but that would have also been a lie. His reaction to her had not been unusual. Women were women after all. Their bodies were designed to give pleasure, though he had to admit that her body had felt better than most.

No, his trouble began that second morning at sea, as she strolled about the deck. She had unfastened her braid from its fixed circle around her head the day before and had failed to refasten it since. The result was a maddening distraction, for its delicate tips brushed back and forth across her bottom as she moved. When she finally spoke to him he was not in full possession of his wits.

‘It is a lovely morning, is it not?’ she asked.

He opened his mouth to reply, then stopped himself.

She knew that he claimed ignorance of Greek, yet she had asked the question in that language. And in his distraction, he had opened his mouth to respond.

‘It is not my place to pry,’ she began in Latin, ‘or to insert myself in the affairs of those greater than me. I am a slave and you are a soldier, and your life of course is more important than my own. But since we both now find ourselves in service to Egypt’s rightful Queen, I wondered if you might forgive my boldness in asking you a question?’

For a moment he wondered if he was not listening to the questions of a simple slave woman, but to the rhetorical machinations of Cicero himself. ‘Ah, yes, of course,’ he managed.

‘Why did you not bow to him?’

‘Bow to whom? I’m sorry, I do not understand.’

‘Why did you not bow to your commander Titus yesterday when he was taken by the guards?’

‘I did not bow to him? Well, that is uncharacteristic of me. I shall apologise to him when I see him next. He must have been quite affronted.’

Her fix on him was so steady, he began to feel unnerved.

‘Then he must have been doubly offended when you seized his arm.’

Titus ceased his efforts at the oars. ‘I seized his arm? Are you certain?’

‘You do not remember? You held it very tightly.’

For all his rhetorical training, he was uncertain as to how to respond. He coughed out a laugh. ‘Ah! Look there,’ he said, pointing over her shoulder at the rising sun.

She turned. ‘Ra is reborn,’ she said. She looked at him expectantly.

‘I’m sorry, but I do not adhere to the cult of Ra.’

‘May I ask what cult do you subscribe to?’

‘The cult of logic. It is mostly unknown here in Egypt, but in Rome we Stoics revere it.’

‘May I ask what is a Stoic?’

‘One who believes that kings and gods should not steer men’s fates.’

He saw her blink and was satisfied. Egyptians were quite unreasonable when it came to the subject of their gods and he was certain that he had offended her enough to put her off the subject. He noticed the tiny black blades of her lashes.

‘Does the cult of logic have duplicity as its requisite?’ she asked, batting those blades.

‘Excuse me?’

‘You heard me, good Clodius.’

He was stunned into silence. Had she just accused him of lying? But she was a slave. She was not allowed to accuse anyone of anything. ‘I’m sorry, Wen, but you are mistaken. I have known the legate Titus since he was a boy. I am his guard and sometimes his mentor, though I should not be required to explain any of this to you.’

She shook her head, having none of it. ‘Forgive me, but I was valued by my former master for my ability to detect dishonesty and I cannot help but notice that your mouth twitches when you say your commander’s name. I am compelled by my position in service to the Queen—to whom I owe everything—to request from you an honest answer. Whoever you are, I know that you are neither guard, nor mentor, nor simple soldier.’

He was appalled. ‘And whoever you believe yourself to be, it is quite clear that you are just a slave.’

He watched her swallow hard, instantly regretting his words. He had wounded her for certain. She turned back towards the rising sun. When she spoke again, her voice was barely a whisper.

‘It is true that I am low,’ she began, ‘and that I was purchased by the Queen as her slave. As such, I am bound to protect her. But that is not why I do it.’

‘Why do you do it, then?’ he asked, but she ignored his question.

‘You speak of logic. Well, logic tells me not to believe you, for you are a Roman and I have never known a Roman I could trust.’

‘You are a woman for certain, for you are ruled by humours and whims,’ he growled, aware that his own humours were mixing quite dangerously.

A wave hit the side of the boat, causing it to tilt. To steady herself, she placed her hand over his, igniting an invisible spark.

She glared at him before snapping her hand away and stepping backwards. ‘Good Clodius—though I know that is not your name—I would ask that you please not insult my intelligence.’

Her sunny words seemed to grow in their menace. ‘I may not be as big as you, or as smart as you, or as sly as you, but believe me when I tell you that I know how to handle Roman men.’ She flung her braid behind her as if brandishing a whip. ‘If you do anything to endanger the Queen, or our quest to restore her rightful reign, or if your deception results in harm to either the Queen or either of her handmaids, you will be very sorry.’

Her audacity was stunning. No woman had ever spoken to him in such a way.

He refused to give her the satisfaction of revealing his discomposure, however, so he placidly resumed his efforts at the oars, taking care to stay in rhythm with Apollodorus.

Still, his troops were in retreat; they had lost the battle. His unlikely adversary had utilised all the tricks of rhetoric, along with the full force of her personality, to enrage him, then confuse him, and then finally to leave him speechless.

Nor was she yet finished. As the great yellow globe shone out over the shimmering sea, he felt her warm breath in his ear. ‘Just remember that I have my eye on you, Roman.’

He turned his head and there were her lips, so near to his, near enough to touch.

And in that moment, despite everything, he wanted nothing more in the world than to kiss them.

And that was when his real trouble began.

* * *

She could not focus her thoughts. They were like tiny grains of sand, endless in their number, impossible to gather. She told herself that her inattention was the result of her worry about the Queen, but she knew that was not true.

It was because of him.