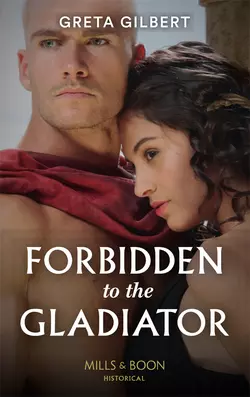

Forbidden To The Gladiator

Greta Gilbert

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 465.10 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: He’ll fight to the deathShe’ll fight to save him!When her father wagers her hard-earned money on a gladiator battle—and loses!—Arria is forced into slavery…just as trapped as the gladiator she blames for her downfall, rugged Cal. She’s furious, yet also captivated by their burning attraction. Cal’s past has made him determined to die in combat, but can Arria give her forbidden warrior something to live for…and a reason to fight for their freedom?