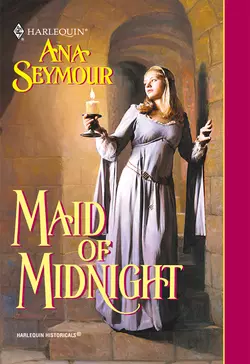

Maid Of Midnight

Ana Seymour

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 387.74 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Bridget had called St. Gabriel′s monastery her home since her mysterious appearance years ago. Kept far from prying eyes amidst the gentle monks, the maiden was happy to care for her protectors. But after reading fanciful tales of Arthur and Guinevere, Bridget yearned for a handsome knight of her very own….On a quest to find his missing brother, Sir Ranulf Brand scoured the Norman countryside. Attacked by brigands and left for dead, he awoke in St. Gabriel′s to visions of a golden-haired angel tending his wounds by candlelight. But the monks assured him ′twas nothing more than a phantom brought on by his injuries. Ye the petal-soft touch of her lips lingered on his mouth still….