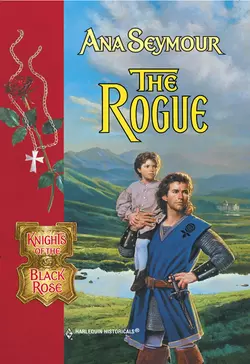

The Rogue

The Rogue

Ana Seymour

When Nicholas Hendry returned safe from the Crusades, he vowed he would no longer woo every comely wench in the shire. But he hadn't counted on the fiery charms of the inkeeper's daughter, Beatrice Thibault. A young miss with no room in her life–or her heart–for him!If Beatrice Thibault had her way, Nicholas Hendry would never learn of the son he had sired. Indeed, the man was more knave than knight in her eyes–no matter how winning his ways or warm his smile, she would never succumb to his charms.

“You are not the man I expected you to be,”

Beatrice said after a long moment.

Nicholas gave a little shudder to shake off the haunting memories, then looked down at her and smiled. “Owen now calls me Papa. Mayhap his aunt should take his example and learn to call me Nicholas. Will you say it for me?”

The flickering shadows of the midsummer twilight lent an air of unreality to the scene. Beatrice’s eyes were inscrutable as she paused, then moistened her lips and said, “Nicholas.”

The word seemed to stir a wave inside him. As it intensified, he suddenly recognized the familiar sensation. With a feeling akin to panic, he tried to tell himself that he was a changed man. Yet as Beatrice swayed ever so slightly closer to him in the shadows, he could not deny his feelings.

He wanted her….

Dear Reader,

This month our exciting medieval series KNIGHTS OF THE BLACK ROSE continues with The Rogue by Ana Seymour, a secret baby story in which rogue knight Nicholas Hendry finds his one true love. Judith Stacy returns with Written in the Heart, the delightful tale of an uptight California businessman who hires a marriage-shy female handwriting analyst to solve some of his company’s capers. In Angel of the Knight, a medieval novel by Diana Hall, a carefree warrior falls deeply in love with his betrothed, and does all he can to free her from a family curse. Talented newcomer Mary Burton brings us A Bride for McCain, about a mining millionaire who enters a marriage of convenience with the town’s schoolteacher.

Whatever your taste in reading, you’ll be sure to find a romantic journey back to the past between the covers of a Harlequin Historicals novel. We hope you’ll join us next month, too!

Sincerely,

Tracy Farrell,

Senior Editor

The Rogue

Ana Seymour

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

Available from Harlequin Historicals and ANA SEYMOUR

The Bandit’s Bride #116

Angel of the Lake #173

Brides for Sale #238

Moonrise #290

Frontier Bride #318

Gabriel’s Lady #337

Lucky Bride #350

Outlaw Wife #377

Jeb Hunter’s Bride #412

A Family for Carter Jones #433

Father for Keeps #458

Lord of Lyonsbridge #472

* (#litres_trial_promo)The Rogue #499

With affection and thanks to my wonderful fellow

Harlequin Historicals authors, especially the team who

brought the KNIGHTS OF THE BLACK ROSE to life—

Suzanne Barclay, Shari Anton, Lyn Stone,

Sharon Schulze and Laurie Grant. And special thanks to

Margaret Moore, who started us all down this path.

Contents

Chapter One (#u8bc2d308-6ee0-5200-a2c4-a8a48bf3ea5c)

Chapter Two (#u8a16fe48-9bac-50ea-98ff-4cb5d37987e3)

Chapter Three (#u343cdd99-5d94-56bc-ba1b-d58c5dc3129c)

Chapter Four (#u036af9b0-9c00-5816-a034-c8a0a11a3156)

Chapter Five (#u1a2d1f49-619c-58bb-bf86-ac541f2a2676)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One

“I’ll not be able to sit straight on my horse if we continue,” Gervase of Palgrave said, shaking away the tankard being pushed at him by the smiling barmaid.

The knight sitting across the table from him frowned, gave an exaggerated blink and stopped the girl’s retreat with a heavy hand on her arm. The tankard clattered to the floor.

“By the saints, Nick, you’re swoggled!” Gervase cried, jumping from his stool. He swatted at his legs where the liquid had splashed his clothes. “I’ll smell like a brewmaster.”

His companion kept his seat but cast a look of remorse at the indignant serving girl. “I beg pardon, sweetheart,” he mumbled, then punctuated the apology with a smile.

Immediately the anger drained from the girl’s round face. “’Twas an accident, milord,” she said, her eyes fixed on the handsome knight. Even masked by the grime of many weeks’ travel, Nicholas of Hendry’s strong features caused most who saw him to take a second look.

As the girl stooped to retrieve the mug and swipe at the spill with her skirt, Gervase seated himself again with a grunt of disgust. “What ails you, my friend?” he asked. “We’re but half a league from Hendry Hall, yet you insist on tarrying here in this sorry excuse of an inn like a bashful bridegroom. Are you not eager to see your family?”

The two knights were the only customers in the tiny inn, which was really just an ale shop, nothing like the bustling establishments they had visited on the long road home.

Nicholas put both elbows on the table and stared into his empty tankard. “Aye.”

“Then, let’s be off, man. I warrant there’s a lady or two who’ll be anxious to see your pretty face again.” He glanced at the serving girl, who had not taken her gaze off Nicholas. “Mayhap more than one or two.”

Nicholas offered the girl another smile and she turned scarlet. She bobbed up and down, holding the tankard in one hand and her sopping dress in the other. “Would the gentlemen, ah, my lords, ah…shall I draw another flagon of ale?”

Nicholas sighed and pushed himself back from the table. “Nay, sweetheart. My friend is right. ’Tis past time for me to reach home.” He stood. “You will accept the hospitality of Hendry Hall this night before traveling on, Gervase?”

Gervase nodded. “I’d like to meet your father. He’ll be a proud man to welcome back a hero son.”

Nicholas gave a humorless laugh. “Surviving makes us heroes, is that it?”

Gervase reached for his gloves and stood. “All returning Crusaders are heroes, Nick.”

“We’ve won nothing, accomplished nothing more than sending a few poor heathens to their own heathen hell. But we’ve struck a blow for Christendom and lived to tell the tale. Aye, you may be right. It might be enough to make my father proud of his son. If so, I don’t know whose will be the greater astonishment—his or mine.”

The two knights started walking out of the inn, Nicholas weaving the first two steps until he gained his equilibrium. “Surely not,” Gervase protested, steadying his friend with a hand on his elbow. “How could a father not be proud of a son like you—a superb horseman, deadly with a sword, quick-witted, not to mention that devil’s countenance that has melted the hearts of half the maidens between here and Sicily?”

“There’s the rub, precisely. My father was always disappointed that I neglected those first attributes you mentioned in favor of the last.”

“He disapproved of your female conquests?”

Nicholas squinted as they walked out into the sunlight. “’Twas a vacillation between disapproval and disgust, I believe. He claimed I curried trouble by what he called my ‘irresponsible attachments.”’

His companion gave Nicholas a sideways glance. The lean, blond Gervase was only a couple of years older than Nicholas, but his expression was much less world-weary. His blue eyes were clear and innocent. “There were many, then?” he asked, his voice softly curious.

“Aye. Many.”

They’d almost reached their horses when the girl who had been serving them in the inn came running out the door and called to them, “Begging yer pardon, my lords.”

They turned toward her. “What is it, girl?” Gervase asked.

Her eyes on Nicholas again, the girl, shuffling her feet in obvious discomfort, said, “The master said ye was to pay fer the spilled ale, my lords. I’d not ask it meself, but he said ye was to pay.”

Gervase looked toward the inn, then at Nicholas. “Do you know the owner, Nicholas?” he asked.

Nicholas shook his head slowly, as if trying to clear it. “It’s been nearly four years. I don’t remember. Who’s your master, sweetheart?” he asked the girl.

“Master Thibault, sir,” she said. “I’d not ask it myself,” she repeated with another nervous bob.

“Thibault the brewer?” Nicholas asked. “Phillip Thibault is master of this place?”

The girl bobbed in confirmation.

“You did spill the drink, Nick,” Gervase said. “Pay the chit and let’s be on our way.”

But Nicholas shook his head. “Tell Master Thibault we’d speak directly with him.”

“Very good, milord.” The girl turned and ran into the inn.

“I’ll give you the coin,” Gervase offered, “if it will get us on the road.”

Nicholas didn’t answer his friend. His eyes were fixed on the door of the inn, but the person who emerged was obviously not Thibault the innkeeper. It was a woman, tall and slender. As she marched toward them, Nicholas could see that her features were finely chiseled, her nose straight and narrow, her cheekbones high.

“Might this be one of your conquests, Nick?” Gervase asked under his breath. “Because methinks the lady has had a change of opinion since your departure. I see daggers in those blue eyes.”

“I know her not,” Nicholas answered, puzzled himself by the woman’s obvious animosity.

She didn’t speak until she was practically on top of them. Then she said, “So ’tis truly you. I didn’t believe it when they told me. We’d thought you dead. I’d hoped you dead.” As she finished speaking, she set her feet apart, rocked up on her toes and spit square in his face. Then she whirled around and stalked back into the inn.

The two knights looked at each other in astonishment, Nicholas wiping the spittle from his face with the back of his hand.

Finally Gervase broke the silence with a shaky smile. “My friend, I’ve had second thoughts about asking your instruction in matters of the heart.”

“I swear, Gervase, I never set eyes on her,” Nicholas insisted as the two knights rode side by side along the dusty road to Hendry Hall. After the young woman had disappeared inside the inn, Gervase had argued Nicholas into continuing on their journey at once, rather than waiting to see if the innkeeper shared the lovely spitfire’s hostility. “Do you think I’d not remember a woman like that?”

“She seemed to know you right enough.”

“Aye. And I’ll have an answer to that mystery, but now I’m for Hendry Hall.”

“Am I seeing at last a glimmer of eagerness to be home?”

Nicholas shifted in his saddle. “They said at the inn that they’d thought me dead. No doubt my arrival will be a surprise.”

“We six were all counted among the departed when we didn’t come back directly at the end of the fighting.”

Just six. Of the two hundred knights who’d ridden off four years before proudly flaunting the banner of the Black Rose, only the six comrades-in-arms had returned. Level-headed Simon, the natural leader of the group; Nicholas, the charmer; Bernard, battle-hardened from humble squire to deadly conquerer; Guy, the outlander who was rightfully the lord’s son; Gervase, the innocent who’d taken a vow none of the others would dare; and Hugh, whose soft-hearted manner disguised a warrior’s strength.

“I thought the news of our miraculous survival would make our welcome all the merrier,” Gervase continued when Nicholas remained silent.

“Hendry Hall is not a merry place, Gervase, which is perhaps why I was wont to seek friendlier diversions away from home.”

“By the saints, Nicholas, if all your diversions were like the one we just met, I’d say you’d find friendlier ground back fighting the infidels.”

Nicholas shook his head. “And still you refuse to believe me. The lady was not my lover.” He stared ahead at the gray stone manor house that had come into view around the bend in the road. He’d always favored buxom maids with pleasing smiles and easy ways. The woman at the inn had had a strength to her, no matter how willowy her form. And there’d been steel in her gaze. “Trust me, Gervase,” he said softly. “I’d have remembered such a one as she.”

Beatrice crooned softly as she rocked the sleeping boy in her arms. “’twas in the merry month of May, when green buds were a-swellin’…”

She enjoyed these quiet evening times with her little nephew, though she knew that he would soon be beyond such attentions. Over three years old now, he seemed to grow bigger daily.

The door to her bedchamber creaked open. “Do you think to sit here the rest of the night, daughter?” Phillip Thibault asked softly, taking one step into the room.

“Flora was right, Father,” she answered, still rocking, and rubbing her hand lightly over the child’s dark curls. “Handsome as the devil himself, she used to say. Dancing black eyes that can melt the innards of whatever woman they light upon.”

“You should come down to sup, lass. You’ve taken nothing since this morning, and that was before dawn.”

Beatrice’s glance slid to her father. Her blue eyes were icy without a hint of tears. “As handsome as the devil and twice as wicked, I trow.”

Phillip shook his head sadly. “Put little Owen in his bed and come downstairs with me. Gertie left a leg of mutton that’s fair charred on the spit while I’ve waited for you.”

“You should have supped, Father. I’ve no taste for food this night.”

Phillip walked across the room. His daughter’s bedchamber was large, encompassing half the upper floor of the Gilded Boar. It had once been the master’s quarters, but when Beatrice had come from York to care for her sister, Phillip had insisted on moving to the small room at the rear of the inn. He’d stayed there now that the big upstairs chamber served as both sleeping quarters and nursery. The big bed Phillip had shared years ago for too short a span with Beatrice and Flora’s mother was pushed up against one slanting wall. The rest of the room was devoted to the child’s needs.

“You’ll be a fine nursemaid to the lad on the morrow after a day of fasting,” Phillip said sternly, reaching for the child. “He’ll be awake with the cock’s crow, running every which way and begging to be off to the meadow while you slump over your porridge.”

Owen murmured as his grandfather lifted him, but remained asleep. Beatrice watched nervously as her father carried the child across the room. Phillip was not strong these days, and at times the shaking made it difficult to keep his balance. She let out a little sigh of relief as her father placed the boy successfully on his pallet.

“I cannot stomach the thought of food while that blackguard’s face still dances before my eyes,” she said.

“Then banish him from your mind, Beatrice. You need not have any contact with Master Hendry.”

“With Sir Nicholas Hendry, you mean,” she corrected bitterly. “You forget he’s a hero now, returning from the Holy Crusade.”

Phillip took her hand and pulled her out of the chair. “Ah, you see. He couldn’t be such a devil after all if he’s spent the past four years on the Lord’s work.”

Beatrice let her father lead her out of the room. “’Tis more likely that he’s spent the past four years seducing every maid between here and Jerusalem.”

Phillip shook his head again slowly and pushed gently on his daughter’s shoulders to start her moving down the narrow stairs to the tavern room. “Put him out of your head, lass. With any luck he’ll be so busy over at Hendry Hall that we won’t soon see his face again.”

Nicholas bit his lip as he gave Gervase a full forearm grip. The younger knight’s free hand went to Nicholas’s shoulder. “We’ll meet again, my friend,” he said, his voice thick.

Nicholas nodded without speaking.

“I’ll stay on a few days if you need me, Nick. If you need help with…you know…settling your father’s affairs.”

“It appears they’ve been well settled without me,” Nicholas answered with a shake of his head. “Though I can still scarcely credit it. I’d thought my father too tough to ever let death catch up with him.”

“’Twas not the homecoming you’d planned.”

“Nay.”

The two knights let their hands drop and Gervase moved toward his horse, saying, “You’ll give my thanks to your lady mother for the night’s lodging?”

“Aye.”

Gervase mounted his big stallion. “We’ve a brotherhood, you know, Nick, the six of us. Knights of the Black Rose. We’re the only ones left to tell the stories.”

Nicholas ventured a wan smile. “I know. Forgive this melancholy farewell, Gervase. I count you as a brother and always shall.”

“There’s nothing to forgive, Nick. You’ve come back to find a house of mourning. It will take you some time to get used to the idea that you’re the new master of Hendry Hall.”

Nicholas shook his head once again. He’d not told Gervase the true extent of the bad news he’d learned from his mother last night after the rejoicing at his safe return had subsided. “Aye, it will take time,” he said simply. He gave the horse a gentle slap. “Now off with you, my friend, to put your own affairs to rights. You, too, return to a house much altered.”

Gervase gave a sad smile. “You know me like a brother as well, Nicholas. I’ll send word when I’m settled.”

Nicholas nodded and forced a smile to his lips as his friend rode off. Saying goodbye to the last of his comrade knights put an end to the adventure that had at times seemed part of a four-year-long dream. Now it was time to awaken. Past time. Gervase’s horse disappeared around the bend. His shoulders set, Nicholas turned back toward the house where his newly widowed mother waited.

“That’s the third time you’ve invoked the name of Baron Hawse in the past five minutes, Mother,” Nicholas said wearily. “I care nothing for the baron’s thoughts on the matter. I want to know yours.”

The mistress of Hendry Hall was a tiny woman, totally dwarfed by her strapping son, but her gaze did not waver. “Baron Hawse has been my savior, Nicholas. I’d likely have perished without him, thinking both you and your father dead.”

“I grant you it must have been difficult, Mother, but now I’m back and Hendry Hall can be restored to its rightful master. I mislike the idea that the ghost of my father has been chased away by the presence of our neighbor to the south. If I recall, Father thought little of the man.”

Constance turned away from her son’s gaze and walked a few steps to sit on the low stoop by the small fireplace that had been a recent improvement to the spacious master’s chambers of Hendry Hall. When alive, Nicholas’s father, Arthur, had been constantly rebuilding the stone house that had started as a much more humble abode shortly after the days of the Conquest.

Nicholas looked down at his mother. At twoscore years, she was an old woman, yet in the flickering firelight her face was devoid of lines, her eyes clear. After a long moment she turned her head back to him and said, “As I recall it, you and your father were too often at odds for you to know much about what he thought.”

Nicholas hesitated a moment, then crossed the room to drop down beside her directly in front of the fire. “Aye. ’Twas the principal thing that I was determined to change. I’ve thought of little else this year past as we struggled to make our way home.”

Constance reached out to her son and gently brushed an unruly lock of hair from his forehead. “I know. ’Tis a bitter pill that you two were never reconciled. But, Nicholas, in my heart I know that your father truly did love you.”

Nicholas looked away from her as he said, “Aye. He loved me so much that he signed away my birthright to a man he didn’t even like.”

“He thought you dead, Nicholas. And he respected the baron’s position. To him that was the most important thing. He was trying to protect me.”

Nicholas leaned toward the flames and felt the welcome heat on his face. The house had not entirely given up the chill of the long winter months. “I still can’t believe it—Baron Hawse as master of Hendry lands and Hendry Hall.” He looked up at his mother. “And of the mistress of Hendry Hall as well, from the way you speak of him.”

“The only man who has ever been my master is dead, Nicholas. And I’ve no desire to lease myself to a new one.”

“Yet the baron is in want of a wife. ’Twould be a natural match.” Nicholas finally voiced the thought that had been in his head since his mother had told him how his father, on his deathbed, had signed over his estate to Gilbert, Baron Hawse.

“Mayhap. But ’tis not a match I seek. And I’d mourn your father this twelvemonth before I’d even consider such a notion.”

Though her words were a denial, something in her tone told Nicholas that the idea of marrying the baron had, indeed, occurred to his mother. The thought made the back of his mouth taste sour.

His bad leg had gone stiff. He untwisted it and rose awkwardly to his feet. “By the rood, Mother, you deserve happiness after enduring my father all those long years. But I intend to fight Hawse on this matter of the Hendry lands. I’d hoped you’d not let your heart get in the way. Women are ever soft on these matters.”

Constance gave a sad smile. “Before you went off to the war, the rumor was that you were something of an expert on the subject of women’s hearts, my son. I confess I’d hoped that the years away would have taught you something about their heads as well.”

“The Crusades taught me many things, Mother. You’ll not find me the reckless philanderer who fled here four years ago. I’ve grown up.”

“I’m glad to hear it.” The firelight caught the brightening of her eyes.

“But the Crusades also taught me to fight my own battles. Hendry Hall belongs to me, in spite of the documents my father signed.” He rubbed his thigh where the old wound nagged.

“The baron will be here on the morrow,” his mother said. “He has made no move to implement the change in title, and has promised not to act until the mourning year is over. Mayhap we can come to a peaceful resolution.”

“Mayhap.” He bent to plant a kiss on the top of his mother’s head. “Don’t fret yourself, Mother. You’ve had too many worries since my father’s death. Now that I’m home, I’d see the smile back on your face.”

She obliged him with the broadest smile she’d given since he had arrived on the previous day. “My prayers have been answered by your return, my son.”

He turned to leave, moving gingerly as the feeling came slowly back into his leg. As he reached to open the door, he was startled by a knock that sounded from the other side. He pulled it open to reveal his mother’s handmaid.

The girl was breathing heavily, evidently having just run up the steep stairway to the upstairs bedchambers. “Visitor’s awaiting, Master Nicholas,” she puffed.

Nicholas looked back at his mother. “I thought you said the baron was coming tomorrow.”

“’Tis not Baron Hawse,” the girl said. “’Tis a lady. Not a fine one, but not common neither.”

“One of your former admirers, no doubt, son,” said Constance with an air of resignation. “I thought it would not take them long to discover your return.”

Nicholas frowned and turned to follow the servant girl downstairs.

Chapter Two

The news that had awaited him upon his arrival home had almost made him forget the incident at the Gilded Boar Inn. But even before he entered the great hall and saw the tall woman waiting for him at the opposite end of the hall, he somehow suspected that his surprise visitor might be her.

Oddly enough, the thought rather pleased him. For one thing, it would give him the opportunity to solve the mystery of her dramatic response to his visit to the inn the previous noon.

She looked up as he approached. Once again, her eyes were like skewers. However, this time he had ample opportunity to observe that they were also handsome, as was the rest of her. “Mistress,” he said in acknowledgement. When she didn’t speak at once, he decided to be direct. “You have the advantage of me. You seem to know who I am, but I remain in ignorance of your identity.”

Her chin went up a notch. “I did not come here to make your acquaintance,” she said.

Her voice was musical, he noted, in spite of the frost. “Then you admit that we are not acquainted, mistress. Yet it appears that you must bear me some ill will.” He rubbed a hand across his chin. “I’m quite sure that when I left this country ’twas not the custom to greet perfect strangers by expectorating in their faces.”

Beatrice felt unexpectedly shaky. She hadn’t thought it would be this difficult to face the monster. Her father had argued against this visit, and perhaps she should have paid him heed. But she had a reason for wanting to be sure that Nicholas Hendry would never again set foot anywhere near the Gilded Boar. The sudden memory of little Owen strengthened her resolve.

“The gesture was spontaneous,” she said. “But I offer no apology. And you may believe that the sentiment behind it was genuine.”

Nicholas’s dark eyes warmed to the edge of a smile. “I believe you, mistress.”

His lack of anger made her task more difficult. “Be that as it may, I’ve come to be sure that the message was received.”

Nicholas merely tipped his head, questioning.

“You’re not welcome at the Boar,” Beatrice continued.

Now he frowned. “Who are you, mistress? And how is it that you are warning me away from an inn that, if I calculate correctly, is on lands leased from this very estate?”

Beatrice felt her face grow warm. If she were to accomplish her mission, she had to tell him that much. “The master of the inn, Phillip Thibault, is my father.”

Nicholas blinked as though a sudden memory had shifted in the back of his head. “You’re not Flora,” he said, his voice low.

“So you do remember her?”

“Aye. The brewer’s daughter, Flora. But you are not she.”

“Flora was my sister.” Her voice held steady.

“Was?” He looked stricken. She’d give him that much, at least.

“Flora’s dead these three years past.”

Nicholas looked down. “It grieves me to hear it.” Lifting his eyes to his visitor’s face, he asked, “What happened to her?”

Beatrice swallowed the lump that threatened to erupt from her throat. It was anger she wanted to show this man, not grief. “You killed her,” she said finally.

Nicholas’s shock was more acute than on their earlier encounter when she had spit at him. He remembered sweet Flora vividly. She’d been his last light o’ love before he’d set out on the Crusade. They’d had but a few short meetings before he had to take leave of her. He remembered her tender farewell, had tasted her tears all the way across the Channel.

You killed her, the woman had said, hate dripping with each word. He shook his head to clear it, and felt the beginning of anger. He may have taken unfair advantage of Flora Thibault, as he had too many other women in those wild days. But he’d never harmed her, of that he was certain.

“She was in perfect health when I left England,” he said stiffly.

“She died of a broken heart.”

Nicholas shook his head. Broken hearts were the stuff of minstrel songs. People did not die of them. Perhaps this woman, however intelligent she appeared, was of weak mind. The notion made him speak more gently. “Flora knew from the onset that our time together would be short. I can’t believe that my departure caused her such distress.”

“If you’d truly known my sister, you would have seen that she was in love with you.”

“We loved each other, Mistress Thibault, but we both knew ’twas a fleeting pleasure. I swear your sister understood this as well as I.”

“Yet she is dead,” Beatrice said, delivering each word as if it were a judge’s sentence.

“Did she have no disease, no wound?”

Beatrice ignored his question and continued in her deliberate tone. “I can do nothing to prove you accountable, Master Hendry, but listen well. I’ve come to ask you civilly to honor my father’s grief and my own. Do not show your face anywhere near the Gilded Boar.”

“I’d speak with your father, mistress. I want—”

Beatrice held up a hand to stop his speech. “We have many friends in the village, sir. If you’ll not heed my words, you might find your welcome home much less warm than you had hoped.”

Nicholas shook his head in wonderment. What kind of woman was this to come threatening the master of the estate, ordering him to stay off a portion of his own property? Or what should be his property, he amended. Perhaps it was already known throughout the territory that Baron Hawse was the new master at Hendry.

He took a long moment to consider his reply. Finally he said, “I’ve returned determined to heal old wounds, mistress, not to open them. But your father looked upon me kindly once, and I’d have him know that I had nothing to do with his daughter’s death.”

Beatrice’s shakiness had subsided, but her head was feeling muddled. She’d prepared herself for an angry confrontation with her sister’s former lover. She’d rehearsed the words she would hurl at him. But she was finding it hard to rail against his measured tones and sad countenance.

Her fingers moved restlessly at her sides in the folds of her overskirt. “I speak for my father as well as myself,” she said. “’Twould be a kindness to a grieving family if you would stay away.”

His nearly black eyes were steady and grave. There was not a hint of the playful charmer her sister had talked of with such incessant longing. “Then I’ll honor your wishes and his, Mistress Thibault. But please tell your father that I share your grief. I’ll mourn sweet Flora as I do my own father.”

It was all Beatrice could do to make her way across the big room and out the door to the courtyard. Nothing about the interview had gone as she had planned. She’d thought to feed her three-year long anger on his arrogant words. Instead, she’d found herself feeling almost sorry for the pain she’d brought to him with her news.

The crisp spring air helped. She took a great gulp of it and willed herself to slow her pace as she walked along the gravel path to the unfenced stone pillars that marked the entrance to Hendry Hall. She’d accomplished her mission. She had his promise not to come to the Boar, and that was all that counted.

The village of Hendry was small. When Owen grew old enough to run about on his own, he’d no doubt cross paths with the master of Hendry Hall. But if her luck held, Sir Nicholas would never suspect his connection to the boy.

Amazingly enough, it had not even occurred to him that Flora’s death might have been the result of giving birth to a child he had left planted inside her. Just like a man, Beatrice thought, relieved to feel her anger returning.

She reached the pillars and looked to the left at the sound of a horse approaching. Even from a distance, she knew the rider. Baron Hawse was a familiar sight in the neighborhood. His lands surrounded the Hendry estate and he’d never been shy about venturing onto Hendry lands as if he and not the Hendry family were the overlord.

She stopped and waited. She’d not bow her head to him, but neither did she want to be so rude as to turn her back and walk away.

“Mistress Thibault, is it not?” the baron called as he approached. “Did you have some business with the lady Constance?”

Beatrice gave an inconclusive murmur. She couldn’t see how her business was any of the baron’s affair, no matter if he was the most important man in the shire.

“Meself, I’ve come to see the returning prodigal—young Nicholas, home from the wars, hale and hearty, in spite of all the accounts to the contrary. ’Tis somewhat of a miracle, hey?”

“Aye,” she answered simply.

The baron pulled his horse up and peered down at her, squinting. “Mayhap ’twas Nicholas you came to see. He always was a one for the ladies.”

The baron was a big man, overspilling his small saddle, but his size was solid bulk, not fat, and his proportions were manly. The only signs of his age were the fine veins that crisscrossed his somewhat bulbous nose, giving his face a florid appearance against the contrast of his snow-white hair. Though he had never said anything improper to her, his glances always made Beatrice feel as if something cold was creeping over her skin.

“Good day to you, milord,” she said, continuing to ignore his questions.

She turned to head in the opposite direction from which the baron had come, but he danced his horse forward a couple of steps, blocking her path.

“So it was Nicholas you came to see,” he said. “I’d thought the boy preferred lasses with soft curves and empty heads. I’d evidently not given him enough credit.”

His eyes watched her, bright with speculation.

“Excuse me, Baron Hawse. I’m just on my way back to the inn, where I warrant my father will be missing me.”

“As I recall, you’ve not lived here long, mistress. You were raised by an aunt in York, I believe? You came only shortly before your sister’s death. Was it on a prior visit that you made Nicholas Hendry’s acquaintance?”

Beatrice was astounded at the extent of his knowledge of her family’s affairs. She’d often heard that the baron knew in intimate detail the comings and goings of all the neighborhood inhabitants, no matter how lowly. But she hadn’t realized the truth of the statement until now.

“I have nothing to do with Nicholas Hendry,” she said bluntly. “Nor do I expect that I ever shall. Now, forgive me, Baron, but I really must be on my way.”

This time Hawse did not prevent her from turning down the road toward the village. The baron sat still on his horse for several moments, watching her leave. Beatrice Thibault was a rare woman, as spirited as she was beautiful. How convenient that with his acquisition of the Hendry lands, she was now one of his very tenants.

It was not widely known in Hendry that he was to be their new master. He’d refrained from taking active control of the lands in deference to Constance. But her year of mourning would soon be past and she would be his wife at last, after all these long years.

Then he’d have no compunction about exerting his lordly rights over the people of Hendry. And he might just start with the haughty Mistress Thibault. The notion turned up his lips in a sly smile of anticipation.

The great hall of the manor occupied the entire rear half of the bottom floor. It had fireplaces at each end, another of Arthur Hendry’s improvements, and a raised dais along the west wall so that the members of the family and their guests could eat at a table raised from the trestles set out for the servants and lesser visitors.

Nicholas had just helped his mother mount the single step to the long table when there was a commotion at the huge double doors leading into the big room. He turned to see the larger-than-life form of their neighbor, lumbering across the room toward him, arms outstretched.

“I found I could not wait another day to see you, Nicholas,” Baron Hawse said, engulfing the younger man in a hearty embrace.

Nicholas tried not to wince. He’d never liked the baron, even as a boy, but for his mother’s sake, he was determined to be civil. He allowed the embrace, then stepped back. “’Tis kind of you to trouble yourself, Baron.”

“Not at all, boy. With your father gone, I feel it’s my place to be here to welcome you. Back from the dead, hey? Not often a man has a chance to welcome someone back from those nether regions.”

The motley assortment of household retainers who had been milling about finding their places at the lower benches stood uncertainly, not wanting to be seated while their new master remained standing.

“I never counted myself dead, Baron,” Nicholas answered dryly. “Though I felt the spectre’s breath a time or two. You’ll join us for supper?”

“Of course, lad,” the baron boomed. “I should have been here last night for your welcome home meal.” He turned a reproving glance on Constance, who also remained standing by her chair. “You should have sent word, my dear.”

Nicholas frowned as his mother bit her lip in embarrassment.

“As you can imagine, Baron,” he said stiffly, “the tidings that greeted me upon my arrival did not exactly put us in the mood for company.”

The baron gave Nicholas a hearty clap on the shoulder and stepped past him up on the dais. “Precisely, lad. I should have been here to deliver the news of your father’s death. Women are over-maudlin about these affairs. No doubt you had all manner of tears and carrying on to contend with.” Once again he looked at Constance, who dropped her gaze to the floor.

Nicholas struggled to keep his temper, reminding himself that the baron had cared for his mother in her bereavement. “My mother’s heart is too tender not to mourn her husband’s passing, Baron Hawse. I do not count that as a fault.”

He followed the baron up on the dais and began to motion him to the bench on the other side of his mother, but the older man stopped at the center of the table, pulled out the lord’s chair and sat. Nicholas’s mouth fell open in astonishment. The previous evening when his mother had urged him to be seated in the master’s place, it had felt sad and odd, but to have his father’s old chair occupied by a stranger seemed nearly intolerable.

He looked at his mother. Her soft brown eyes pleaded with him not to create a scene. Baron Hawse had occupied this chair before, Nicholas realized. As the baron pulled a trencher forward to share with Constance, Nicholas wondered exactly how much of Arthur Hendry’s former life had already been taken over by his neighbor.

Giving his mother a smile of reassurance, he took a seat on the bench to the baron’s left and pulled his own trencher forward. He’d not share a board with this man.

Once the head table was seated, there was a sudden bustle in the room as the other diners sat and the serving girls began to move among the tables with dishes of stew and plates of roasted rabbit with wild berries.

Nicholas ate in silence, speaking only when the baron asked him a direct question. He scarcely noticed the carefully prepared dinner, which his mother had been supervising in the kitchen much of the afternoon. Watching the baron carve off succulent bits of rabbit and offer them on his knife to Constance’s mouth was making Nicholas lose his appetite.

“I’m sure he’ll be pleased to, won’t you, son?” His mother’s soft voice broke through his gloomy thoughts.

He looked from Constance to the baron, who both appeared to be waiting for him to speak. “I beg your pardon,” he mumbled. “I would be pleased to what?”

“To visit us at Hawse Castle two days hence,” the baron supplied. “If you’ve fully recovered from your journey.”

“I’d thought to begin seeing to the estate here. I’ve a meeting with the steward on the morrow to go over the accounts and—”

“Well, then, that’s perfect,” the baron interrupted. “You can join us at Hawse the next day and we’ll see where we stand on this matter of the estates. I have all the papers your father signed before his death, of course.”

Nicholas’s eyes narrowed. “Papers that he signed thinking me dead.”

The baron’s hearty voice did not waver. “Of course. Which is why we have much to discuss, you and I. We’ll discuss your father’s plans for this place.”

Nicholas pushed away his board, leaving the rabbit mostly untouched. “My father’s plans for Hendry were to pass it on to his only son. No amount of discussion will alter that.”

Hawse smiled. “Indeed.” He reached out a big hand and gave a painful squeeze to Nicholas’s forearm. “I have some plans of my own to discuss with you, lad. I believe we can work our way out of this unfortunate tangle. Come see me the day after tomorrow.”

“We’ll both go,” Constance said quickly. “It would be churlish to refuse my lord’s hospitality after all you’ve done for me.”

Hawse turned toward Constance and gave her a smile that even to Nicholas looked almost tender.

“’Tis not within your power to be churlish, Lady Constance,” he told her, his voice softening.

Nicholas pushed back his bench and stood. “In two days hence, then. We’ll attend you at Hawse Castle. Now if you’ll excuse me, I am still, as you say, fatigued from my journey.”

Without taking further leave of them, he turned and made his way out of the room.

He sat in the dark looking out the deep window of his bedchamber into the moonlit yard below. It was early for sleep, but he didn’t feel like talking to anyone, not even the servants, so he had retired to his room and had not lit the wall torch near his bed.

The knock on his door was so soft, he almost didn’t hear it. For several moments, he resolved to let the caller go unanswered, but then he thought that perhaps his mother needed him, so he reluctantly got to his feet and crossed over to open the door. The visitor was a woman, but definitely not his mother.

Mollie had changed little in the four years since he’d last seen her. If anything, her breasts spilled even more voluptuously from the scanty, thin blouse. Her sparkling green eyes glinted even more wickedly with invitation.

“So, ye’ve come back, ye naughty boy,” she laughed, twining her arms around his neck with such energy that it pushed him back into the room.

In spite of himself, Nicholas felt a flare of desire course through him as the serving maid’s soft contours wriggled against him. He dropped a light kiss on her lips and gently pried her hands loose. “Hallo, sweetheart,” he said.

She took a step back and thudded her small fist into his chest. “For shame, Nicky. I’ll not listen to yer ‘sweethearts’ after ye ran away like that without so much as a farewell buss.”

Mollie had been one of the most good-natured of his lovemaking partners. A full five years older than Nicholas, she’d had a string of lovers herself and understood that their friendship was nothing more than the mutual satisfaction of shared passions.

Nicholas grinned at her and captured the hand that continued pounding him with little effect. “You’ll always be my sweetheart, Mollie. You know that.”

She pulled her hand out of his and laid it tenderly along his cheek. “Aye, Nicky. We were fair eager for it in those days, weren’t we?”

Unexpectedly, Nicholas was suddenly eager once again. He put a hand at Mollie’s waist and pulled her toward him, but she pushed away. “Aye, we were,” he murmured.

“Ah, Nicky. I’ve not come for that.” She pushed him away. “I’m a proper goodwife now.”

Nicholas dropped his hands from her as if he’d been burned. “Wife?”

“Aye, these three years past. Got meself two young’uns.”

He blinked in astonishment. “Babies?”

Mollie laughed and gave him a friendly pat on his chest. “What did ye think comes of all that gallivanting in the corn, Master Hendry? Ye were always a careful one, but not all are like that.” A brief shadow crossed her face, but then she giggled and added, “I knew I’d end up round as a herring barrel some day.”

Her words added to his gloom. Merry, passionate, carefree Mollie. A wife and mother. It was hard to believe. “Are you happy, Mollie?” he asked finally. “Is your husband a good man?”

She smiled and nodded. “Aye, Nicky, he is. Ye do know him. ’Tis Clarence, the baker.”

Nicholas had a vague memory of a big, quiet man, perhaps twenty years his senior, who ran the bake shop at the edge of the village and sent fresh bread to the manor each day. A pleasant yeasty odor always seemed to cling to the man.

“Then I’m happy for you, Mollie. You deserve a good man and a good life.”

“As do we all, Nicky,” she agreed softly. “Well, I’d best be getting back before the wee ones start howling for their mum.”

Nicholas shook his head, still trying to reconcile the picture of Mollie caring for two youngsters. “I’m glad for you, Mollie,” he told her.

“And I to see ye back here and not a ghost, ye great lug.” She grinned. “I said a mass for ye, now there’s a tale’ll spin yer head.”

“A mass?”

“When they said ye was dead. I went into the church, proper like. That and me wedding are the only two times I’ve ever gone inside.”

Nicholas smiled. “I’m obliged to you, Mollie.”

“Take care, Nicky,” she said quickly. She stretched up on tiptoes to kiss him full on the mouth, and she was gone.

It was late. All activity in the yard below had long since ceased. But Nicholas was still not ready to stretch out on his pallet and sleep. Mollie’s visit had left him even more restless than before. Jovial, generous Mollie. Married and a mother. At least she was happy, and to all appearances her dalliance with Nicholas had not done any damage to her life. Some of the other women he’d loved and left might not be so forgiving.

How would Flora have greeted him, he wondered, if she were alive? He could not imagine that her reception would have been anything like the one given to him by her sister. Flora had been the soul of sweetness.

He sighed and paced the length of his room. When he’d thought all was lost on the Crusades, he’d sworn that if he ever got back to England, he’d lead a better life. He would make it up to the women he’d wronged. He would show his father that he was the kind of son Arthur Hendry had always wanted. Now his father was dead. At least one of his lovers was happily married and had all but forgotten about him.

But there were still amends to make. And he intended to begin the process immediately. He’d start on the morrow. With Flora.

Chapter Three

No one knew the origins of the little village formerly called Hendry’s Lea and now simply Hendry. The old ones told tales of ancient times when spirits walked about and the druids held ceremonies out on the wide meadow to the north. The name predated the current Hendry family, they claimed, and certainly was around long before Hendry Hall. But since there had now been several generations of Hendrys connected to the place, ending with the returned-from-the-dead heir, most of the villagers took it as natural that it was to Nicholas that they owed allegiance.

There was little resentment over the system. The Hendrys had always been magnanimous landlords. If a family found itself a bit hard-pressed when it came time to collect the twice yearly rents, it never occurred to them that they would be turned off their lands for nonpayment. Indeed, it was not unusual for the Hendrys themselves to see that a few extra coins appeared at the needy household.

After Arthur’s death, there had been some consternation in the village as the rumors spread that some new land baron from the court would appear and undo several generations of Hendry generosity. However, as the months went on with no apparent change, the rumors subsided.

Nevertheless, the sudden appearance of Nicholas was a cause for rejoicing in the village, at least in the households where there was no irate father waiting to nail Nicholas’s hide to the door for having enticed his willing daughter.

Nicholas had awakened before dawn with his head throbbing from the ale with which he’d finally drunk himself to sleep the previous evening after Mollie’s visit. But the bright spring day and the villagers’ hearty greetings as he rode through town lifted his spirits. He was pleased that he remembered many of their names. Little by little the life he had left four years ago was returning to him. Only this time, he would live it more honorably than he had in his thoughtless youth.

The stone church at the far end of the village had not changed. No doubt more graves had been added, but the mossy ground of the churchyard covered the new as well as the old, camouflaging any recent arrival.

He tied his horse to a newel on the sunny side of the church and walked the worn path around the building to the graves. The stone column in the center of the yard said Hendry, but Nicholas gave it only a passing glance. The monument was old. Recent generations of the family, including his father, were buried in a small crypt at the back of Hendry Hall itself.

The morning sun didn’t reach this place, and Nicholas shivered as he walked among the headstones, scanning the names. He knew Phillip Thibault would not have seen his daughter laid to rest without proper marking.

He saw her mother’s first. Laurette, beloved wife. A smooth, unmarked stone stood beside that, no doubt awaiting Phillip’s arrival. It was the kind of gesture he would expect from the man. And beyond the blank stone was the one he’d been seeking. Flora, beloved daughter.

Nicholas walked the edge of the three graves and knelt at the far end. His hand traced the inscription on the stone. Flora. Such a cold, hard memorial for the warm, loving young woman he had known. Over and over he traced it, his eyes closed. He tried to picture her face. It had been alive and vital, he recalled, but the memory was dim. He knew that her eyes had danced when he’d lifted her onto his big horse. She’d loved to ride. Once in the Holy Lands he’d seen a girl on a pony and he’d thought to himself, When I get back to England I’m going to get Flora her own horse, a little mare as sweet and gentle as her owner.

His eyes prickled, then burned under the closed lids. He’d shed no tears for his father, but they came, unbidden, for Flora. Little Flora, whose pretty face he could no longer clearly remember.

He opened his eyes, blinked rapidly and gave an unmanly sniff. His old leg wound was telling him to change from his kneeling position, but he hesitated a moment, feeling as if he should do something more. He should have gathered some spring wildflowers from the meadow before he’d come, he thought. Flora had loved flowers. She’d made him a garland one afternoon and had hung it around his neck, laughingly proclaiming him King of the May.

He took a deep, ragged breath, then, impulsively, pulled the silver chain from around his neck. It held a tiny cross. He’d worn it all through the years abroad and it had come to be a talisman to him. He weighed it in his palm for a moment, then gently tucked it into the mossy grass just at the base of Flora’s tombstone. “Rest in peace, sweet Flora,” he whispered.

His head bowed, he didn’t see the woman coming around the corner of the church, but he heard her gasp plainly.

“What are you doing here?” she asked, her voice shaking.

Nicholas rose awkwardly to his feet, resisting the urge to rub his bad leg. His mental image of the sweet, departed Flora was replaced by the real life vision of her sister, face flushed with anger. “I come on the same mission you do, I’d suppose, mistress. To pay my respects to Flora.”

“’Twas more than you paid to her when she was alive.” Beatrice was carrying the wildflowers he’d neglected to bring. She brushed past him and scattered them equally over her sister’s grave and her mother’s.

Nicholas watched her distribute the flowers, then said, “I’ll not fault you for your words, since you no doubt are grieving your sister sorely. But I’ll tell you again that I never held Flora in disrespect. I was greatly fond of her.”

She dropped the last flower, then straightened up. Their faces were mere inches apart, her eyes glacial. For a long moment neither said a word.

“I’ll not argue the point standing over her grave,” she said finally. “But perhaps you will do me the respect of allowing me to mourn in private.”

Still their gazes held, and Beatrice was certain that Nicholas Hendry had more that he wanted to say to her. But after a moment, he nodded and said only, “As you wish.” Then with one final glance at the carved stone name, he turned and walked away.

She stood for several minutes until he had disappeared behind the church. His appearance there had left her feeling shaky. Could it be true that his eyes had been rimmed with red? she asked herself. It simply did not fit with the picture of Nicholas Hendry she’d been holding all these years to think of him weeping over her sister’s grave.

She gave herself a shake and sank to her knees beside the grave. Then she cocked her head as she noticed something glinting near Flora’s tombstone. Picking the object from the ground, she looked at it. It was a silver cross, suspended from a chain. Beatrice’s eyes widened. On her visit to Hendry Hall the previous day, she’d seen this very cross hanging from Nicholas Hendry’s neck.

She sat back, stunned. Could this be the callous knight she had pictured—this man who wept at his former lover’s grave and left his necklace as tribute?

Tears welled in her eyes. “Ah, Flora,” she said in a low voice. “Do you know that your knight has returned from the Crusades at last? Did you see him here, little sister? He’s left you a holy cross.”

She leaned over and pressed her warm cheek to the cool, mossy ground. “Help me not to hate him, Flora. Help me to understand why Nicholas Hendry came back from the dead and you never shall.”

Then she lay against the softly mounded grass and wept.

Owen was playing in his special cave. Phillip had made it from an old ale barrel that he had cut so that it rested on its side and made a perfect hiding place for a three-year old. Beatrice kept one eye on the child while she carefully poured hot tallow into the candle molds.

There were no customers in the inn that afternoon, which was not an unusual occurrence, and she’d sent the barmaid Gertie home early.

“He killed your daughter, and yet you defend him,” she said to her father, who watched her from his bench on the other side of the fire.

“I’m not defending him, lass, but neither did he kill Flora.” He looked over at the barrel where two protruding shoes were the only evidence of the child inside. Lowering his voice, he continued, “’Twas the childbirth that killed her, just as it did your mother. Both were too frail for birthing.”

“Flora would never have been birthing if it hadn’t been for Nicholas Hendry.”

“And your mother would not have given birth if it hadn’t been for me. Does that make me a murderer, too?”

His voice cracked with long held pain, and Beatrice felt a stab of remorse. Setting aside the mold, she crossed over to her father and dropped to her knees beside him, and put her arms around his shoulders. “Forgive me, Father. Let’s not speak any more of Nicholas Hendry. I’d be happy never to hear the man’s name again.”

“Now, that’s not likely. He’s our landlord and our neighbor.” Phillip pulled out of his daughter’s embrace and turned to her, his aging eyes watery. “This bitterness will solve nothing, Beady. What’s more, resentment works like a wicked little worm inside a person, gnawing away until you’re left with a rotted hole where your heart should be.”

A ghost of a smile crossed her lips at his use of her old childhood nickname. “’Twas my mother first gave me that name, was it not?” she asked.

Phillip smiled and stroked the hair back from her forehead. “Aye, our little Beady. What I wouldn’t give to have her see you now, a woman grown, proud and beautiful.”

His hand shook as he withdrew it from her hair. The palsy grew worse with each passing week, Beatrice noted with the familiar mix of sadness and fear. What would she and Owen do when her father was no longer around?

She gave him another squeeze, then got to her feet as the barrel across the room began rocking furiously back and forth. A small head poked out the entrance.

“Bear!” the child proclaimed, his dark eyes dancing.

Beatrice walked over to the contraption and hunched down at the mouth. “Did a bear come into your cave, Owen?” she asked.

Owen nodded, giggling.

“A big one?”

“Aye, fearsome big.” Bears had been Owen’s number one preoccupation since his grandfather and aunt had taken him to see one dance at the May Day fair. It had been a motheaten, sorry creature who could barely lift itself onto its hind legs, much less dance or look fierce, but to the child it had been a wonder.

“Did you wrestle with it?” Beatrice asked.

“Aye. It runned away.”

Both Beatrice and Owen turned their head toward the door as if following the departure of the imaginary beast. “I’m glad to hear it,” she said. “Bears aren’t allowed in the inn. Mayhap you’d like some porridge after such a fierce battle.”

Owen stuck his feet up in the air against the rim of the barrel and somersaulted backward, landing in Beatrice’s lap. “With a sweetcake?” His dark eyes pleaded with her from his upside down position.

She pulled him upright and hugged him. “Aye, with a sweetcake, if you finish your porridge. Warriors who want to fight bears need a lot of good food.”

He followed along beside her happily to one of the long tap room trestle tables. His hair was tangled from the tussle with the bear and she unconsciously combed it into place with her fingers. If she could help it, Flora’s child would never have to face any more adversity than an imaginary bear.

Out of the corner of her eye, she watched her father lift himself from his bench, trying to disguise what an effort it cost him.

They sat around the table and Owen lisped the quick prayer she had taught him, “God bless Mama Flora.” It came out as one word, “Gobblesmaflor.” Undoubtedly it meant little to the child, but Beatrice found the ritual comforting.

Phillip reached across the table and put his hand on his daughter’s. “I’ve not a doubt that our blessed Flora has found peace in another world, daughter. Would that her sister could find a measure of it in this one.”

Beatrice pulled her hand gently away from her father’s grasp and began ladling the bowls of porridge.

The rumor mill had it that a century before in Normandy, the Hawses had been mere peasants who had made their way up into the ranks of first a knight’s army and then a duke’s by their strength in combat. In any event, it was certain that the present Baron Hawse’s father had been made baron and granted title to considerable lands after returning from the ill-fated Third Crusade in which King Richard had ended up an ignominious prisoner. The senior Hawse had thrown his fortunes to the king’s brother, John, at precisely the correct moment and had then further ingratiated himself with the new king supporting him when most of the nobles of the land rebelled.

Gilbert, the present Baron Hawse, did not suffer close inquiries into the Hawse lineage. His power in the shire was nearly absolute. The Hendry lands and the small village of Hendry, which his estate encircled, were the only interruptions in his dominion. Now that wrinkle had been solved with his acquisition of the lands through Arthur Hendry’s deathbed grant, though he’d carefully refrained from pressing the claim while Constance Hendry was still in mourning. Sooner or later he intended to have Hendry’s wife, as well as his lands, but the baron was exercising uncharacteristic patience where Constance Hendry was concerned.

Nicholas had visited Hawse Castle a number of times in his youth, but the sight of it never failed to impress him. Built like a fortress, though the days of Norman-Saxon conflict were long over, the towering stone structure was surrounded by a stone wall with battlements on all sides.

As he and his mother rode through the raised portcullis into the bailey, he almost felt as if he should have come garbed in the chain mail armor that had become like a second skin during his years on the Crusades.

The baron, however, was anything but warlike as he strode across the courtyard to greet them, smiling broadly.

“Welcome to Hawse, my friends,” he called. A woman trailed behind him, unable to keep up with his pace. He looked back over his shoulder at her and barked, “Come along, Winifred.”

Winifred was the baron’s only child, a slender young woman who looked to Nicholas as frail as her father looked robust. He remembered her only vaguely, but was surprised to see her there. She was a few years older than Nicholas himself, and by now he would have thought that she’d be married and off running a castle of her own somewhere.

“I bid you welcome,” she said, her voice so soft he could scarcely hear the words. Her eyes were on Constance and only darted nervously to Nicholas for a moment.

Nicholas had always had a natural affinity for putting even the shyest of women at ease. He took her cold hand and raised it toward his lips. “It’s good to see you again, Winifred,” he said gently. “You’ve grown into a beauty in my absence.”

Winifred blushed with pleasure and let her eyes meet Nicholas’s at last. Baron Hawse beamed at the two younger people and took Constance’s arm. “Let’s be out of this wind,” he said. “The table is ready with Hawse Castle’s finest fare for our honored guests. Winifred has seen to it.”

“’Twas kind of you,” Nicholas murmured. He gazed down at her with the seductive smile he had always reserved for females of a proper age to be bedded, and he received the usual response. Her eyes softened, her lips fell open slightly.

Nicholas shook himself. His actions came as natural to him as breathing, but he’d best be wary. Winifred Hawse was not a barmaid, and he had no intention of bedding her. Indeed, if he was to become the reformed man he’d sworn to become on the field of battle, he’d do well to save his smiles for grandmothers and holy sisters.

His concern at the moment was resolving the tangle over the Hendry estates. He’d banish all thoughts of women from his mind until the matter was settled. Unbidden, he had a sudden vision of Beatrice Thibault, as she’d looked just inches away from him at the cemetery.

“I may still call you that?”

Nicholas looked down, startled by Winifred’s soft voice.

“I beg your pardon,” he said.

“I may still call you Nick, as I did when we were young?” she repeated.

He had no recollection of Winifred Hawse calling him anything at all, but he smiled at her and said, “I’d be injured if you didn’t.”

He offered his arm to her as they turned to follow his mother and her father across the yard and into the castle keep.

“I’m only saying that you should consider the baron’s suggestion,” Constance told her son gently. Nicholas sprawled at the foot of his mother’s pallet, as had been his custom when he was young. She sat up against the cushions, a shawl wrapped around her against the morning cold. “Winifred is a lovely girl.”

Nicholas sighed. “Aye, Mother. But I’m not interested in taking a wife. I’ve barely returned home. I just want to settle this matter and take my rightful place as master of Hendry.” He sat up to throw another blanket over his mother, who had begun to shiver. “We need to build fireplaces in these chambers.”

Constance smiled. “You’ve inherited that trait from your father, at least. He was always wanting to make some change or other to this place.”

“Little good it will do me to inherit his character traits if I’m not to inherit his estate,” Nicholas grumbled.

“It’s more than generous of Baron Hawse to make this offer, Nicholas. You will not find a better match than Winifred in all England. Some day you could inherit all the Hawse lands.”

“The baron is still virile enough to remarry and father a son,” Nicholas observed, watching his mother carefully.

His remark elicited no reaction. “Aye,” she replied evenly. “But he has remained unwed these many years since his wife’s death. Another heir does not seem to be a matter of high importance to him.”

Nicholas could not say why the idea of taking Winifred Hawse to wife seemed so wrong. She was not unpleasant to look upon. Her demeanor was graceful and ladylike. She was, as his mother pointed out, heiress to a considerable fortune. But somehow the idea of marrying her seemed impossible. For one thing, she was so fragile, he couldn’t imagine sharing with her the lusty games he’d played with his former partners such as the curvaceous Mollie.

“I’m not ready to marry, Mother. And I shouldn’t have to marry in order to inherit what is rightfully mine.”

Constance swung her feet to the stone floor. “Take some time to think about it, my son. You’ve just arrived home and all of this has come at you too quickly. We’ll invite the baron and his daughter to a dinner here next sennight and see how you’re feeling then. Now run along and send my maid to help me dress.”

She stood and crossed the room toward the private garderobe, another of his father’s improvements. Nicholas uncurled himself from the bed and left the room to go find her handmaid.

The red-haired servant was in the scullery with two other young girls of the manor. They stopped their chatter when Nicholas entered the room, but all three looked him over from head to toe, their blushing faces glowing with eager smiles. Nicholas had a moment of longing for his earlier, heedless days when he would have taken full advantage of the girls’ shameless admiration.

“Good morrow, ladies,” he said with a slight bow. “I’d thought the sun was the brightest thing about this morn until I saw your smiles.”

They giggled and one of the girls, whose name he didn’t know, ventured a sally in reply. Then he told his mother’s maid that her service was needed and bid them good day.

Their laughter floated with him as he made his way out to the courtyard, but it did not make him want to turn back and choose one on which to work his wiles. To his surprise, he realized that all his protestations that he was a changed man were very much the truth. He was changed. He wanted something more in life than a quick romp in the hayrack with one of the scullery maids.

He wasn’t sure exactly what that something was. But, by the rood, he was certain that it was not marriage to Baron Hawse’s only daughter.

Chapter Four

At the risk of encountering former lovers who might not be as forgiving of past transgressions as Mollie, Nicholas vowed to spend the next few days getting reacquainted with both the Hendry lands and the people he still thought of as his tenants. He put Baron Hawse’s offer of marriage to Winifred out of his mind and asked his mother not to bring the matter up again until the Hawse’s scheduled dinner the following week.

Spring was blossoming in earnest, and riding in the rolling countryside around Hendry Hall lifted Nicholas’s spirits. His big destrier, glad to be roaming free after the difficult journey, pranced along like a frisky colt. He’d purchased the bay stallion in the Holy Lands when his own had been killed by an Arab’s lance.

Nicholas laughed out loud and bent over the animal’s neck. “Aye, Scarab, ’tis easier without three stone’s weight of armor and bloody heathens running at you like crazed devils, is it not?”

As if in reply, the horse settled into a long, smooth gallop. Nicholas threw back his head. The sun on his face and the wind in his hair made him feel truly at ease for the first time since he’d returned to England.

He pulled Scarab up as he reached the top of the hill that looked down upon Hendry. The Gilded Boar Inn stood slightly apart from the village, out on the main highway that led back to Durleigh. Nicholas’s good humor faded as he surveyed the modest inn. With a sigh he reined his mount to the north to skirt around it. Much as he’d like to see Phillip Thibault, Flora’s sister had asked him to honor their grief and stay away. He felt duty-bound to comply with her wishes, at least for the time being.

Eventually, when he’d reestablished himself at Hendry and the ownership of the estate was no longer in dispute, he’d seek Phillip out in private. He’d always liked the old man, and he felt the need to assure him that, in spite of Beatrice’s bitter accusations, he had never meant to do Flora any harm.

He steered a path straight into the village itself, heading for the third in the row of humble wooden homes. Here, at least, he would be assured of a welcome. Growing up he’d spent as much time in the Fletchers’ humble cottage as he had at Hendry Hall. More than once a manservant from the hall had to be sent to fetch him when he’d stayed on too many hours and his mother had grown worried.

The Fletcher household had always seemed much happier than his own. Ranulf the Fletcher and his wife, Enid, had raised a brood of seven children. Harold, the middle boy, had been exactly Nicholas’s age, and the two had been as close as brothers. When Ranulf had died the year Harold and Nicholas turned sixteen, Harold had taken over his father’s trade. By then Nicholas had been sent to squire at Durleigh Castle, and the difference in station had begun to put distance between the two friends, but the bond had never been entirely broken.

Harold had a workshop at one side of the cottage, and if the gray smoke billowing out from the three-sided structure was any indication, he was hard at his task.

Nicholas walked his horse around to the open side of the workshop. Harold was bent over a workbench with feathers scattered everywhere. Nicholas pulled Scarab to a halt and sat watching his old friend. Harold looked much the same as when the two lads had first begun to vie over which village lass they would next woo. But Nicholas’s mother had told him that Harold now had a wife and son of his own. It was hard to credit.

As if aware that he was being studied, Harold looked up suddenly. He squinted out into the sunlight, then let the arrow in his hand clatter to the ground, swung his leg over the bench and started toward Nicholas.

“I’d heard ye was back, Nicky!” he called. “Back from the dead, they say, but I told them all along that no bloody heathen arrow was going to put an end to Nicholas Hendry.”

Nicholas slid off his horse and met Harold halfway. With a slight moment of hesitation, Harold stopped in front of him and extended his hand. Nicholas ignored the gesture and, instead, engulfed his friend in a great bear hug, which Harold willingly returned.

“Aye, but ’tis good to see you, Harry,” Nicholas said with a broad smile.

Harold leaned back and gave his friend a critical look from head to toe. “They’ve left you none the worse, I trow.” He knocked his fist into Nicholas’s upper arm. “Ye’ve grown more solid, if anything. Might even be able to take me in a fall or two.”

“I’ve always been able to take you in a fall or two, you scrawny lout.”

The two old friends grinned at each other, for a moment lost back in their youth, ignoring the different paths their lives had taken.

Harold playfully gave a sideways kick to Nicholas’s leg in an old wrestling move, but dropped his grin when Nicholas’s bad leg buckled beneath him. “Forgive me—” he began.

Nicholas shook his head and tried to keep from wincing. “Nay, ’tis nothing. They whittled at me a bit,” he added, rubbing his thigh.

Harold frowned. “Arrow?”

Nicholas shook his head. “Lance.”

Harold gave a low whistle. “Then ’tis somewhat of a miracle after all that ye came back to us. Mayhap me mum was right to say prayers for ye.”

“Enid? How is she?”

“Salty and ornery and fit as a woman half her age.”

Nicholas laughed. “I’m glad to hear it. And what’s this about a new young fletcher in the village? Taking your trade yet, is he?”

To Nicholas’s amazement, his friend’s face flushed with pride. “My boy, Nick. Ah, he’s a scrappy youngster, he is. Who’d have thought ’twould be such a marvelous thing to have a son?”

“What do you call him?”

Harold hesitated a moment, then answered, “He’s named after my best friend, who I thought never to see again this side of heaven or hell.”

Nicholas swallowed and, for the second time in a week, felt tears sting the back of his eyes. For a long moment, he made no reply, then he clapped Harold on the back and said, “Well, then, take me to see the boy. He must be a scrappy lad indeed with such a name.”

“Mayhap they’ll not come into the cottage,” Jannet Fletcher said, giving Beatrice a little pat of reassurance.

The two women had heard a rider approaching and, spying through the cracks in the shutters, had seen the greeting between the two men. “I warrant they will,” Beatrice argued. “Harold will want to show off his household.”

Jannet stepped back from the window and took a quick look around the simple cottage, suddenly aware that her housekeeping was about to be under examination. She retrieved a pair of leggings that had been left by the fireplace to dry. “Well, the boys are off with Enid, so you don’t have to worry about him seeing Owen.”

Beatrice turned away from the window as well, her arms folded and her forehead creased with worry. “Your mother-in-law could come back at any moment with both boys in tow.”

Jannet straightened up from her cleaning and looked directly at her friend. “Beatrice, you can’t expect to keep Owen hidden from him forever. He’s a bright active boy and soon he’ll want to have the run of the village just like all the other children.”

Beatrice grabbed her arms, trying to keep from shaking. What incredibly bad luck that she should be visiting the Fletchers just at the moment that Nicholas Hendry chose to make an appearance. “He can’t see him, Jannet. Not yet. He’s just learned about Flora’s death, and if he sees the child, it might set him thinking.”

Jannet picked up a broom from the side of the fireplace and swept some cinders back on to the hearth. “No one knows that Owen is Nicholas Hendry’s son, am I right?”

“My father knows. But you’re the only other person we’ve told.”

“And you made me swear not to tell a living soul. I’ve kept my vow. I’ve not even told Harold.”

Beatrice crossed the room and grabbed her friend’s hands as they clung to the broom. “You must especially not tell Harold, Jannet. He’s Nicholas’s friend. You promise me?”

“I’ve promised, Beatrice. I’ll not betray your trust. But I think you might want to reconsider your decision to keep this a secret. Nicholas could do good things for Owen. Even baseborn, he could still become a squire and then a knight—”

“A knight? So he could go off to fight in faraway lands and return to us maimed or not at all? ’Tis not a life I would choose for him.”

Jannet shook her head, but her answer was interrupted by the creak of the door. Sunlight filled the room, then was blotted out as the doorframe was filled by the tall figure of Nicholas Hendry.

Harold stood just behind him, his hand on his friend’s shoulder. “Jannet, ’tis Nicholas, home from the wars.” He peered over Nicholas’s shoulder, squinted into the darkness and added, “Ah, Beatrice, I’d forgotten you came to visit with—”

Beatrice stepped forward and grabbed her shawl from the table. “I was just leaving, Harold,” she said, interrupting him.

The two men moved into the room and Harold looked around, puzzled. “Where are the boys?”

“With Enid out in the meadow,” Jannet said quickly. She walked around Beatrice and gave a little curtsy in front of Nicholas, whose eyes were on Beatrice. “How d’ye do, Sir Nicholas? I’ve heard much of you from my good husband.”

Nicholas turned his head toward her and made a little bow in reply. “I’ve not yet had the opportunity to hear the same about you, mistress, but I already know you to be a canny young woman for choosing a husband like Harold.”

“For shame, Nick,” Harold protested. “’Twas I who chose her, not the other way round.”

Nicholas grinned. “’Tis always the woman does the choosing, Harold. Did you not learn any of the lessons I taught you?”

Beatrice paid little attention to the banter. She was determined to escape from the cottage and out toward the meadow to intercept Enid before the old woman could return with the two boys. “Good day to you Harold, Master Hendry,” she said, nodding to each man in turn. “If you’ll excuse me, I’ll take my leave.”

It was his fourth encounter with Beatrice Thibault, Nicholas mused, as he stepped to one side to allow her to pass, and the ice in her voice had not thawed a bit. He supposed he should be grateful that at least she had not spat at him in front of his friend.

She brushed against him and went quickly out the door. On impulse, he said to Harold, “I’ll be back directly,” and followed her outside. “Hold a moment, Mistress Thibault,” he called to her as she walked quickly toward the road.

She turned back to him, her face set with annoyance. He took a few loping steps to catch up to her. “What is it?” she snapped.

He took a deep breath. “Is there nothing I can say to make you stop hating me?” he asked.

She blinked, obviously taken aback by the question. “I…I don’t know.”

Nicholas took her confusion as encouragement. “We may meet again, you know, here in the village or at church or at your sister’s grave. By my reckoning, ’tis pointless to carry on as if there were some kind of feud between us. Flora would be the last person to want that, you know. She was too sweet a soul to tolerate enmity of any kind.”

Beatrice stiffened. “I don’t need you to tell me what kind of person my sister was, Master Hendry,” she said. But her voice was less harsh than it had been moments ago.

“I’d never presume to do so,” he said softly. “They say the bond between sisters is a very special one.”

His gentleness seemed to have some effect. Her eyes misted as she answered, “Aye. Though raised apart we were no less close.”

For the first time her expression held more sadness than anger. It made her look softer. Nicholas felt a sudden urge to put his arms around her in comfort. Instead he said, “She often spoke of you, mistress, in the short time we had together.”

Beatrice blinked back the threatening tears and looked as if she was about to make some reply when suddenly there were childish shouts in the distance. Her face blanched. “I must leave,” she said. Before Nicholas could protest, she’d whirled around and began running down the road.

He watched her for a few moments, sorry that the sudden swell of emotion had made her flee just when it looked as if they might be able to heal some of the hard feeling between them. He’d made a start, he thought, uncertain as to why the idea gave him such satisfaction.

Belatedly remembering his manners and the purpose of his visit, he turned back to the Fletchers’ cottage. Harold and Jannet were waiting for him, looking concerned.