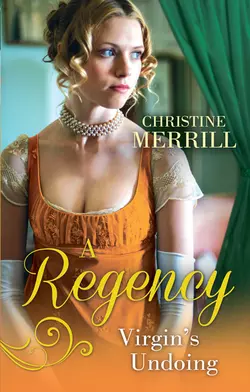

A Regency Virgin′s Undoing: Lady Drusilla′s Road to Ruin / Paying the Virgin′s Price

Christine Merrill

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 774.44 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Lady Drusilla’s Road to RuinLady Drusilla Rudney’s sister has eloped and to prevent a scandal Dru has appealed to Captain John Hendricks to help bring her sister home. But Dru’s unconventional beauty soon makes John want to forget gentlemanly conduct… and create a scandal all of their own!Paying the Virgin’s PriceGambler Nathan Wardale may not be a gentleman, but when he wins his opponent’s daughter’s virginity in a card game he has no intention of claiming his winnings. Yet, when he lays eyes on Diana Price, his honour wavers under the temptation to possess his prize…