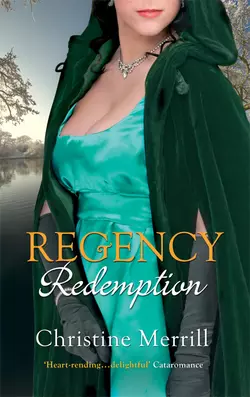

Regency Redemption: The Inconvenient Duchess / An Unladylike Offer

Christine Merrill

A hasty proposal…Compromised and wedded on the same day, Lady Miranda was fast finding married life not to her taste. A decaying manor and a secretive husband were hardly the stuff of girlish dreams. Yet every time she looked at dark, brooding Marcus Radwell, Duke of Haughleigh, she felt inexplicably compelled – and determined to make their marriage real!Ruin or Redemption?Miss Esme Canville’s brutal father is resolved to marry her off. Instead, she’ll offer herself to notorious rake Captain St John Radwell and enjoy all the freedom of a mistress! But St John is intent on mending his rakish ways and now his resolve must resist the determined, beautiful, and very, very tempting Esme…Two classic and delightful Regency tales!

REGENCYRedemption

The Inconvenient Duchess

An UnladylikeOffer

Christine Merrill

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

About the Author

CHRISTINE MERRILL lives on a farm in Wisconsin, USA, with her husband, two sons, and too many pets—all of whom would like her to get off the computer so they can check their e-mail.

She has worked by turns in theatre costuming, where she was paid to play with period ballgowns, and as a librarian, where she spent the day surrounded by books. Writing historical romance combines her love of good stories and fancy dress with her ability to stare out of the window and make stuff up.

Don’t miss these other Regency delights from Mills & Boon

Historical romance’s bestselling authors!

REGENCY PLEASURES

Louise Allen

REGENCY SECRETS

Julia Justiss

REGENCY RUMOURS

Juliet Landon

REGENCY REDEMPTION

Christine Merrill

REGENCY DEBUTANTES

Margaret McPhee

REGENCY IMPROPRIETIES

Diane Gaston

REGENCY MISTRESSES

Mary Brendan

REGENCY REBELS

Deb Marlowe

REGENCY SCANDALS

Sophia James

REGENCY MARRIAGES

Elizabeth Rolls

REGENCY INNOCENTS

Annie Burrows

REGENCY SINS

Bronwyn Scott

The Inconvenient Duchess

Christine Merrill

To Jim, who knows I’m crazy,

but loves me anyway. And to James and Sean.

Making your own breakfasts and mating your own socks

builds character. You’ll thank me later, but I thank you now.

Chapter One

‘Of course, you know I am dying.’ His mother extended slim fingers from beneath the bedclothes and patted the hand that he offered to her.

Marcus Radwell, fourth Duke of Haughleigh, kept his face impassive, searching his mind for the appropriate response. ‘No.’ His tone was neutral. ‘We will, no doubt, have this conversation again at Christmas when you have recovered from your current malady.’

‘Only you would use obstinacy as a way to cheer me on my deathbed.’

And only you would stage death with such Drury Lane melodrama. He left the words unspoken, struggling for decorum, but glared at the carefully arranged scene. She’d chosen burgundy velvet hangings and dim lighting to accent her already pale skin. The cloying scent of the lilies on the dresser gave the air a funereal heaviness.

‘No, my son, we will not be having this conversation again. The things I have to tell you will be said today. I do not have the strength to tell them twice, and certainly will not be here at Christmas to force another promise from you.’ She gestured to the water glass at the bedside. He filled it and offered it to her, supporting her as she drank.

No strength? And yet her voice seemed steady enough. This latest fatal illness was probably no more real than the last one. Or the one before. He stared hard into her face, searching for some indication of the truth. Her hair was still the same delicate blonde cloud on the pillow, but her face was grey beneath the porcelain complexion that had always given her a false air of fragility. ‘If you are too weak … perhaps later …’

‘Perhaps later I will be too weak to say them, and you will not have to hear. A good attempt, but I expected better.’

‘And I expected better of you, Mother. I thought I had made it clear, on my last visit to your deathbed—’ the word was heavy with irony he could no longer disguise ‘—that I was tired of playing the fool in these little dramas you insist on arranging. If you want something of me, you could at least do me the courtesy of stating it plainly in a letter.’

‘So that you could refuse me by post, and save yourself the journey home?’

‘Home? And where might that be? This is your home. Not mine.’

Her laugh was mirthless and ended in a rasping cough. Old instincts made him reach out to her before he caught himself and let the hand fall to his side. The coughing ended abruptly, as though his lack of sympathy made her rethink her strategy.

‘This is your home, your Grace, whether you choose to live in it or not.’

So if fears for her health would not move him, perhaps guilt over his neglected estate? He shrugged.

Her hand trembled as she gestured towards the nightstand, and he reached for the carafe to refill her glass. ‘No. The box on the table.’

He passed the inlaid box to her. She fumbled with the catch, opened it and removed a stack of letters, patting them. ‘As time grows short, I’ve worked to mend the mistakes in my past. To right what wrongs I could. To make peace.’

To get right with the Lord before His inevitable judgement, he added to himself and clenched his jaw.

‘And recently, I received a letter from a friend of my youth. An old school companion who was treated badly.’

He could guess by whom. If his mother was planning to right her wrongs chronologically, she had better be quick. Even if she lived another twenty years, as he suspected she might, there were wrongs enough in her past to fill the remaining time.

‘There were money problems, as there so often are. Her father died penniless. She was forced home and had to find her own way in the world. She has been, for the last twelve years, a companion to a young girl.’

‘No.’ His voice echoed in the still sickroom.

‘You say no, and, as yet, I have asked no questions.’

‘But you most certainly will. The young girl will turn out to be of marriageable age and good family. The conversation will be about the succession. The question is inevitable and the answer will be no.’

‘I had thought to see you settled before I died.’

‘Perhaps you shall. I am sure we have plenty of time.’

She continued as if there had been no interruption. ‘I let you wait, assuming you would make a choice in your own good time. But I have no time. No time to let you handle things. Certainly no time to let you wallow in grief for losses and mistakes that are ten years past.’

He bit off the retort that was forming on his tongue. She was right in this at least. He needn’t reopen his half of an old argument.

‘You are right. The girl is of marriageable age, but her prospects are poor. She is all but an orphan. The family lands are mortgaged and gone. She has little hope of making a match, and Lady Cecily despairs of her chances. She fears that her charge is destined for a life of service and does not wish to see her own fate visited on another. She has approached me, hoping that I might help …’

‘And you offered me up as a sacrifice to expiate the wrong you did forty years ago.’

‘I offered her hope. Why should I not? I have a son who is thirty-five and without issue. A son who shows no sign of remedying this condition, though his wife and heir are ten years in the grave. A son who wastes himself on whores when he should be seeing to the estate and providing for the succession. I know how quickly life passes. If you die, the title falls to your brother. Have you considered this, or do you think yourself immortal?’

He forced a smile. ‘Why does it matter to you now? If St John inherited the title, it would please you above all things. You’ve made no effort to hide that he is your favourite.’

She smiled back, with equal coldness. ‘I am a fond old woman, but not as foolish as all that. I will not lie and call you favourite. But neither will I claim that St John has the talent or temperament to run this estate. I can trust that once you are settled here, you will not lose your father’s coronet at cards. Your neglect of your duties is benign, and easily remedied. But can you imagine the land after a year in your brother’s care?’

He closed his eyes and felt the chill seeping through his blood. He did not want to imagine his brother as a duke any more than he wanted to imagine himself chained to a wife and family and trapped in this tomb of a house. There were enough ghosts here, and now his mother was threatening to add herself to the list of grim spirits he was avoiding.

She gave a shuddering breath and coughed.

He offered her another sip of water and she cleared her throat before speaking again. ‘I did not offer you as a sacrifice, however much pleasure you take in playing the martyr. I suggested that she and the girl visit. That is all. From you, I expect a promise. A small boon, not total surrender. I would ask that you not turn her away before meeting her. It will not be a love match, but I trust you to realise, now, that love in courtship does not guarantee a long or a happy union. If she is not deformed, or ill favoured, or so hopelessly stupid as to render her company unbearable, I expect you to give serious thought to your offer. Wit and beauty may fade, but if she has common sense and good health, she has qualities sufficient to make a good wife. You have not, as yet, married some doxy on the continent?’

He glared at her and shook his head.

‘Or developed some tragic tendre for the wife of a friend?’

‘Good God, Mother.’

‘And you are not courting some English rose in secret? That would be too much to hope. So this leaves you with no logical excuse to avoid a meeting. Nothing but a broken heart and a bitter nature, which you can go back to nurturing once an heir is born and the succession secured.’

‘You seriously suggest that I marry some girl you’ve sent for, on the basis of your casual correspondence with an old acquaintance?’

She struggled to sit upright, her eyes glowing like coals in her ashen face. ‘If I had more time, and if you weren’t so damned stubborn, I’d have trotted you around London and forced you to take your pick of the Season long ago. But time is short, and I am forced to make do with what can be found quickly and arranged without effort. If she has wide hips and an amiable nature, overcome your reservations, wed, and get her with child.’

And she coughed again. But this time it was not the delicate sound he was used to, but the rack of lungs too full to hold breath. And it went on and on until her body shook with it. A maid rushed into the room, drawn by the sound, and leaned over the bed, supporting his mother’s back and holding a basin before her. After more coughing she spat and sagged back into the pillows, spent. The maid hurried away with the basin, but a tiny fleck of blood remained on his mother’s lip.

‘Mother.’ His voice was unsteady and his hand trembled as he touched his handkerchief to her mouth.

Her hand tightened on his, but with little strength. He could feel the bones through the translucent skin.

When she spoke, her voice was a hoarse whisper. The glow in her eyes had faded to a pleading, frightened look that he had not seen there before. ‘Please. Before it is too late. Meet the girl. Let me die in peace.’ She smiled in a way that was more a grimace, and he wondered if it was from pain. She’d always tried to keep such rigid control. Of herself. Of him. Of everything. It must embarrass her to have to yield now. And for the first time he noticed how small she was as she lay there and smelled the hint of decay masked by the scent of the lilies.

It was true, then. This time she really was dying.

He sighed. What harm could it do to make a promise now, when she would be gone long before he needed to keep it? He answered stiffly, giving her more cause to hope than he had in years. ‘I will consider it.’

Chapter Two

The front door was oak, and when she dropped the heavy brass knocker against it, Miranda Grey was surprised that the sound was barely louder than the hammering of the rain on the flags around her. It would be a wonder if anyone heard her knock above the sound of the late summer storm.

When the door finally opened, the butler hesitated, as though a moment’s delay in the rain might wash the step clean and save him the trouble of seeing to her.

She was afraid to imagine what he must see. Her hair was half down and streaming water. Her shawl clung to her body, soaked through with the rain. Her travelling dress moulded to her body, and the mud-splattered skirts bunched between her legs when she tried to move. She offered a silent prayer of thanks that she’d decided against wearing slippers or her new pair of shoes. The heavy boots she’d chosen were wildly inappropriate for a lady, but anything else would have disintegrated on the walk to the house. Her wrists, which protruded from the sleeves of the gown before disappearing into her faded gloves, were blue with cold.

After an eternity, the butler opened his mouth, probably to send her away. Or at least to direct her to the rear entrance.

She squared her shoulders and heard Cici repeating words in her mind.

‘It is not who you appear to be that matters. It is who you are. Despite circumstances, you are a lady. You were born to be a lady. If you remember this, people will treat you accordingly.’

Appreciating her height for once, she stared down into the face of the butler and said in a tone as frigid as the icy rainwater in her boots, ‘Lady Miranda Grey. I believe I am expected.’

The butler stepped aside and muttered something about a library. Then, without waiting for an answer, he shambled off down the hall, leaving her and her portmanteau on the step.

She heaved the luggage over the threshold, stepped in after it, and pulled the door shut behind her. She glanced down at her bag, which sat in its own puddle on the marble floor. It could stay here and rot. She was reasonably sure that it was not her job to carry the blasted thing. The blisters forming beneath the calluses on her palms convinced her that she had already carried it quite enough for one night. She abandoned it and hurried after the butler.

He led her into a large room lined with books and muttered something. She leaned closer, but was unable to make out the words. He was no easier to understand in the dead quiet of the house than he had been when he’d greeted her at the door. Then he wandered away again, off into the hall. In search of the dowager, she hoped. In his wake, she detected a faint whiff of gin.

When he was gone, she examined her surroundings in detail, trying to ignore the water dripping from her clothes and on to the fine rug. The house was grand. There was no argument to that. The ceilings were high. The park in front was enormous, as she had learned in frustration while stumbling across its wide expanse in the pouring rain. The hall to this room had been long, wide and marble, and lined with doors that hinted at a variety of equally large rooms.

But …

She sighed. There had to be a but. A house with a peer, but without some accompanying problem, some unspoken deficit, would not have opened its doors to her. She stepped closer to the bookshelves and struggled to read a few of the titles. They did not appear to be well used or current—not that she had any idea of the fashion in literature. Their spines were not worn; they were coated with dust and trailed the occasional cobweb from corner to corner. Not a great man for learning, the duke.

She brightened. Learning was not a requirement, certainly. A learned man might be too clever by half and she’d find herself back out in the rain. Perhaps he had more money than wit.

She stepped closer to the fire and examined the bricks of the hearth. Now here was an area she well understood. It left a message much more readable than the bookshelves. There was soot on the bricks that should have been scrubbed away long ago. She could see the faint smudges on the walls, signs that the room was long overdue for a good cleaning. She rustled the heavy velvet of the draperies over the window, then sneezed at the dust and slapped at the flutter of moths she’d disturbed.

So, the duke was not a man of learning, and the dowager had a weak hand on the servants. The butler was drunk and the maids did not waste time cleaning the room set aside to receive guests. Her hands itched to straighten cushions, to beat dust out of velvet and to find a brush to scrub the bricks. Didn’t these people understand what they had? How lucky they were? And how careless with their good fortune?

If she were mistress of this house …

She stopped to correct herself. When she was mistress of this house. That was how Cici would want her to think. When, not if. Her father was fond of myths and had often told her stories of the Spartan soldiers. When they went off to war, their mothers told them to come back with their shields or on them. And her family would have the same of her. Failure was not an option. She could not disappoint them.

Very well, she decided. When she was mistress of this house, things would be different. She could not offer his Grace riches. But despite the dirt, the house and furnishings proved he did not need money. She was not a great beauty, but who would see her here, so far from London? She lacked the refinements and charms of a lady accustomed to society, but she’d seen no evidence that his Grace enjoyed entertaining. She had little learning, but the dust on his library showed this was not his first concern.

What she could offer were the qualities he clearly needed. Household management. A strong back. A willingness to work hard. She could make his life more comfortable.

And she could provide him an heir.

She pushed the thought quickly from her mind. That would be part of her duties, of course. And, despite Cici’s all-too-detailed explanations of what this duty entailed, she was not afraid. Well, not very afraid. Cici had told her enough about his Grace, the Duke of Haughleigh, to encourage her on this point. He was ten years a widower, so perhaps he would not be too demanding. If his needs were great, he must surely have found a means to satisfy them that did not involve a wife. If his needs were not great, then she had no reason to fear him.

She’d imagined him waiting for her arrival, as she made the long coach ride from London. He was older than she, and thinner. Not frail, but with a slight stoop. Greying hair. She’d added spectacles, since they always seemed to make the wearer less intimidating. And a kind smile. A little sad, perhaps, since he’d waited so long after the death of his wife to seek a new one.

But he did not seek, she reminded herself. Cici had done all the seeking, and this introduction had been arranged with his mother. She added shy, to his list of attributes. He was a retiring country gentleman and not the terrifying rake or high-flyer that Cici had been most qualified to warn her about. She would be polite. He would be receptive. They would deal well together.

And when, eventually, the details of her circumstances needed to be explained, he would have grown so fond of her that he would accept them without qualms.

Without warning, the door opened behind her and she spun to face it. Her heart thumped in her chest and she threw away the image she’d been creating. The man in front of her was no quiet country scholar. Nor some darkly handsome, brooding rake. He entered the room like sunlight streaming through a window.

Not so old, she thought. He must have married young. And his face bore no marks of the grief, no lines of long-born sorrow. It was open and friendly. She relaxed a little and returned his smile. It was impossible not to. His eyes sparkled. And they were as blue as …

She faltered. Not the sky. The sky in the city had been grey. The sea? She’d never seen it, so she was not sure.

Flowers, perhaps. But not the sensible flowers found in a kitchen garden. Something planted in full sun that had no use but to bring pleasure to the viewer.

His hair was much easier to describe. It shone gold in the light from the low fire.

‘Well, well, well. And who do we have here?’ His voice was low and pleasant and the warmth of it made her long to draw near to him. And when she did, she was sure he would smell of expensive soap. And his breath would be sweet. She almost shivered at the thought that she might soon know for sure. She dropped a curtsy.

He continued to stare at her in puzzlement. ‘I’m sorry, my dear. You have the better of me. As far as I know, we weren’t expecting any guests.’

She frowned. ‘My guardian wrote to your mother. It was supposed to be all arranged. Of course, I was rather surprised when there was no one to meet the coach, but …’

He was frowning now, but there was a look of dawning comprehension. ‘I see. If my mother arranged it, that would explain why you expected …’ He paused again and began cautiously. ‘Did you know my mother well?’

‘Me? No, not at all. My guardian and she were school friends. They corresponded.’ She fumbled in her reticule and removed the damp and much-handled letter of introduction, offering it to him.

‘Then you didn’t know of my mother’s illness.’ He took the letter and scanned it, eyebrows raised as he glanced over at her. Then he slipped off his fashionable dark jacket and revealed the black armband tied about the sleeve of his shirt.

‘I’m afraid you’re six weeks too late to have an appointment with my mother, unless you have powers not possessed by the other members of this household. The wreath’s just off the door. I suppose it’s disrespectful of me to say so, but you didn’t miss much. At the best of times, my mother was no pleasure. Here, now …’

He reached for her as she collapsed into the chair, no longer heeding the water soaking into the upholstery from her sodden gown.

‘I thought, since you didn’t know her … I didn’t expect this to affect you so. Can I get you something … brandy …? Decanter empty again … Wilkins! Damn that man.’ He threw open the door and shouted down the hall, trying to locate the muttering butler. ‘Wilkins! Where’s the brandy?’

So she’d arrived dripping wet, unescorted and unexpected, into a house of mourning, with a dubious letter of introduction, expecting to work her way into the affections of a peer and secure an offer before he asked too many questions and sent her home. She buried her head in her hands, wishing that she could soak into the carpet and disappear like the rain trickling from her gown.

‘What the hell is going on?’ His Grace had found someone, but the answering voice in the hall was clearly not the butler. ‘St John, what is the meaning of shouting up and down the halls for brandy? Have you no shame at all? Drink the house dry if you must, but have the common decency to do it in quiet.’ The voice grew louder as it approached the open doorway.

‘And who is this? I swear to God, St John, if this drowned rat is your doing, be damned to our mother’s memory, I’ll throw you out in the rain, brandy and girl and all.’

Miranda looked up to find a stranger framed in the doorway. He was everything that the other man was not. Dark hair, with a streak of grey at each temple, and a face creased by bitterness and hard living. An unsmiling mouth. And his eyes were the grey of a sky before a storm. Strength and power radiated from him like heat from the fire.

The other man ducked under his arm and strode back into the room, proffering a brandy snifter. Then he reconsidered and kept it for himself, taking a long drink before speaking.

‘For a change, dear brother, you can’t blame this muddle on me. The girl is your problem, not mine, and comes courtesy of our departed mother.’ He waved the letter of introduction in salute before passing it to his brother. ‘May I present Lady Miranda Grey, come to see his Grace the Duke of Haughleigh.’ The blond man grinned.

‘You’re the duke?’ She looked to the imposing man in the doorway and wondered how she could have been so wrong. When this man had entered the room, his brother had faded to insignificance. She tried to stand up to curtsy again, but her knees gave out and she plopped back on to the sofa. The water in her boots made a squelching sound as she moved.

He stared back. ‘Of course I’m the duke. This is my home you’ve come to. Who were you expecting to find? The Prince Regent?’

The other man grinned. ‘I think she was under the mistaken impression that I was the duke. I’d just come into the library, looking for the brandy decanter, and found her waiting here …’

‘For how long?’ snapped his brother.

‘Moments. Scant moments, although I would have enjoyed more time alone with Lady Miranda. She’s a charming conversationalist.’

‘And, during this charming conversation, you neglected to mention your name, and allowed her to go on in her mistake.’ He turned from his brother to her.

His gaze caught hers and held it a moment too long as though he could read her heart in her eyes. She looked away in embarrassment and gestured helplessly to the letter of introduction. ‘I was expected. I had no idea … about your mother.

‘I’m so sorry,’ she added as an afterthought.

‘Not as sorry as I am.’ He scanned the letter. ‘Damn that woman. She made me promise. But it was a deathbed promise, and I said the words hoping her demise would absolve me of action.’

‘You promised to marry me, hoping your mother would die?’ She stared back in horror.

‘I promised to meet you. Nothing more. If my mother had died that night, as it appeared she might, who was to know what I promised her? But she lingered.’ He waved the paper. ‘Obviously long enough to post an invitation. And now here you are. With a maid, I trust?’

‘Ahhh … no.’ She struggled with the answer. It was as she’d feared. He must think she was beyond all sense, travelling unchaperoned to visit strangers. ‘She was taken ill and was unable to accompany me.’ As the lie fell from her lips, she forced herself to meet the duke’s unwavering gaze.

‘Surely, your guardian.’

‘Unfortunately, no. She is also in ill health, no longer fit to travel.’ Miranda sighed convincingly. Cici was strong as an ox, and had sworn that it would take a team of them to drag her back into the presence of the duke’s mother.

‘And you travelled alone? From London?’

‘On the mail coach,’ she finished. ‘I rode on top with the driver. It was unorthodox, but not improper.’ And inexpensive.

‘And when you arrived in Devon?’

‘I was surprised that there was no one to meet me. I inquired the direction, and I walked.’

‘Four miles? Cross-country? In the pouring rain?’

‘After London, I enjoyed the fresh air.’ She need not mention the savings of not hiring a gig.

‘And you had no surfeit of air, riding for hours on the roof of the mail coach?’ He was looking at her as though she was crack-brained.

‘I like storms.’ It was an outright lie, but the best she could do. Any love for storms that she might have had had disappeared when the rain permeated her petticoat and ran in icy rivers down her legs.

‘And do you also like dishonour, to court it so?’

She bowed her head again, no longer able to look him in the eye. It had been a mistake to come here. Her behaviour had been outlandish, but she had not been trying to compromise herself. In walking to the house, she had risked all, and now, if the duke turned her out and she had to find her own way home, there would be no way to repair the damage to her reputation.

He gestured around the room. ‘You’re miles from the protection of society in the company of a pair of notorious rakes.’

‘Notorious?’ She compared them. The duke looked dangerous enough, but it was hard to believe his brother was a threat to her honour.

‘In these parts, certainly. Does anyone know you’re here?’

‘I asked direction of a respectable gentleman and his wife.’

‘The man, so tall?’ The duke sketched a measurement with his hand. ‘And plump. With grey hair. The wife: tall, lean as a rail. A mouth that makes her look—’ he pulled a face ‘—a little too respectable.’

She shrugged. ‘I suppose that could be them. If he had spectacles and she had a slight squint.’

‘And when you spoke to them, you gave them your right name?’

She stared back in challenge. ‘Why would I not?’

The duke sank into a chair with a groan.

His brother let out a whoop of laughter.

The duke glared. ‘This is no laughing matter, you nincompoop. If you care at all for honour, then one of us is up a creek.’

St John laughed again. ‘By now you know the answer to the first part of the statement. It would lead you to the answer to the second. I suppose that I could generously offer—’

‘I have a notion of what you would consider a generous offer. Complete the sentence and I’ll hand you your head.’ He ran fingers through his dark hair. Then he turned slowly back to look at her. ‘Miss … whatever-your-name-is …’ He fumbled with the letter, reread it and began again. ‘Lady Miranda Grey. Your arrival here was somewhat … unusual. In London, it might have gone unnoticed. But Marshmore is small, and the arrival of a young lady on a coach, alone, is reason enough to gossip. In the village you spoke with the Reverend Winslow and his wife, who have a rather unchristian love of rumour and no great fondness for this family. When you asked direction to this house, where there was no chaperon in attendance, you cemented their view of you.’

‘I don’t understand.’

St John smirked. ‘It is no doubt now well known around the town that the duke and his brother have reconciled sufficiently after the death of their mother to share a demi-mondaine.’

‘There is a chance that the story will not get back to London, I suppose,’ the duke said with a touch of hope.

Which would be no help. Because of her father, London was still too hot to hold her. If she had to cross out Devon, too … She sighed. There was a limit to the number of counties she could be disgraced in, and still have hope of a match.

St John was still amused. ‘Mrs Winslow has a cousin in London. We might as well take out an ad in The Times.’

The duke looked out of the window and into the rain, which had changed from the soft and bone-chilling drizzle to a driving storm, complete with lightning and high winds. ‘There is no telling the condition of the road between here and the inn. I dare not risk a carriage.’

The look in his eyes made her wonder whether he expected her to set off on foot. She bit back the response forming in her mind, trying to focus on the goal of this trip. A goal that no longer seemed as unlikely as it had when Cici first suggested it.

‘She’ll have to stay the night, Marcus. There’s nothing else for it. And the only question in the mind of the town will be which one of us had her first.’

She gasped in shock at the insult, and then covered her mouth with her hand. There was no advantage in calling attention to herself, just now. Judging by the duke’s expression, he would more likely throw her out into the storm than apologise for his brother’s crudeness.

St John slapped his brother on the back. ‘But, good news, old man. The solution is at hand. And it was our mother’s dying wish, was it not?’

‘Damn the woman. Damn her to hell. Damn the vicar. And his pinched-up shrew of a wife. Damn. Damn!’

St John patted his apoplectic brother. ‘Perhaps the vicar needs to explain free will to you, Marcus. They are not the ones forcing your hand.’

The duke shook off the offending hand. ‘And damn you as well.’

‘You do have a choice, Marcus. But Haughleigh?’ The title escaped St John’s lips in a contemptuous puff of breath. ‘It is Haughleigh who does not. For he would never choose common sense over chivalry, would he, Marcus?’

The duke’s face darkened. ‘I do not need your help in this, St John.’

‘Of course you don’t, your Grace. You never do. So say the words and get them over with. Protect your precious honour. Waiting will not help the matter.’

The duke stiffened, then turned towards Miranda, his jaw clenched and expression hooded, as if making a great effort to marshal his emotions. There was a long pause, and she imagined she could feel the ground shake as the statement rose out of him like lava from an erupting volcano. ‘Lady Miranda, would you do me the honour of accepting my hand in marriage?’

Chapter Three

‘But that’s ridiculous.’ It had slipped out. That was not supposed to be the answer, she reminded herself. It was the goal, was it not, to get her away from scandal and well and properly married? And to a duke. How could she object to that?

She’d imagined an elderly earl. A homely squire. A baron lost in drink or in books. Someone with expectations as low as her own. Not a duke, despite what Cici had planned. She’d mentioned that the Duke of Haughleigh had a younger brother. He had seemed the more likely of the two unlikely possibilities.

And now, she was faced with the elder brother. Unhappy. Impatient. More than she bargained for.

‘You find my proposal ridiculous?’ The duke was staring at her in amazement.

She shook her head. ‘I’m sorry. It isn’t ridiculous. Of course not. Just sudden. You surprised me.’

She was starting to babble. She stopped herself before she was tempted to turn him down and request that his brother offer instead.

‘Well? You’ve got over the shock by now, I trust.’

Of course, she thought, swallowing the bitterness. It had been seconds. She should be fully recovered by now. She looked to St John for help. He grinned back at her, open, honest and unhelpful.

The duke was tapping his foot. Did she want to be yoked for life to a man who tapped his foot whenever she was trying to make a major decision?

Cici’s voice came clearly to her again. ‘Want has nothing to do with it. What you want does not signify. You make the best choice possible given the options available. And if there is only one choice …’

‘I am truly ruined?’

‘If you cannot leave this house until morning, which you can’t. And if the vicar’s wife spreads the tale, which she will.

‘I’m sorry,’ he added as an afterthought.

He was sorry. That, she supposed, was something. But was he sorry for her, or for himself? And would she have to spend the rest of her life in atonement for this night?

‘All right.’ Her voice was barely above a whisper. ‘If that is what you want.’

His business-like demeanour evaporated under the strain. ‘That is not what I want,’ he snapped. ‘But it is what must be done. You are here now, no thanks to my late mother for making the muddle and letting me sort it out. And don’t pretend that this wasn’t your goal in coming here. You were dangling after a proposal, and you received one within moments of our meeting. This is a success for you. A coup. Can you not at least pretend to be content? I can but hope that we are a suitable match. And now, if you will excuse me, I must write a letter to the vicar to be delivered as soon as the road is passable, explaining the situation and requesting his presence tomorrow morning. I only hope gold and good intentions will smooth out the details and convince him to waive the banns. We can hold a ceremony in the family chapel, away from prying eyes and with his wife as a witness.’ He turned and stalked towards the door.

‘Excuse me,’ she called after him. ‘What should I do in the meantime?’

‘Go to the devil,’ he barked. ‘Or go to your room. I care not either way.’ The door slammed behind him.

‘But I don’t have a room,’ she said to the closed door.

St John chuckled behind her.

She turned, startled. She’d forgotten his presence in the face of his brother’s personality, which seemed to take up all the available space in the room.

He was still smiling, and she relaxed a little. At least she would have one ally in the house.

‘Don’t mind my brother overmuch. He’s a little out of sorts right now, as any man would be.’

‘And his bark is worse than his bite?’ she added hopefully.

‘Yes. I’m sure it is.’ But there was a hesitance as he said it. And, for a moment, his face went blank as if he’d remembered something. Then he buried the thought and his face returned to its previous sunny expression. ‘Your host may have forgotten, but I think I can find you a room and some supper. Let’s go find the butler, shall we? And see what he’s done with your bags.’

She’d done it again. Marcus had been sure that six feet of earth separated him from any motherly interventions in his life. He’d thought that a half-promise of co-operation would be sufficient to set her mind at rest and leave him free.

Obviously not. He emptied a drawer of his late mother’s writing desk. Unused stationery, envelopes, stamps. He overturned an inkbottle and swore, mopping at the spreading stain with the linen table runner.

But she’d cast the line, and, at the first opportunity, he’d risen to the bait like a hungry trout. He should have walked out of the room and left the girl to St John. Turned her out into the storm with whatever was left of her honour to fend for herself. Or let her stay in a dry bed and be damned to her reputation.

But how could he? He sank down on to the chair next to the desk and felt it creak under his weight. He was lost as soon as he’d looked into her eyes. When she realised what she had done in coming to his house, there was no triumph there, only resignation. And as he’d railed at her, she’d stood her ground, back straight and chin up, though her eyes couldn’t hide the panic and desperation that she was feeling.

He’d seen that look often enough in the old days. In the mirror, every morning when he shaved. Ten years away had erased it from his own face, only to mark this poor young woman. She certainly had the look of someone who’d run afoul of his accursed family. And if there was anything he could do to ease her misery.

He turned back to the desk. It was not like his mother to burn old letters. If she’d had a plan, there would be some record of it. And he’d seen another letter, the day she suggested this meeting. He snapped his fingers in recognition.

In the inlaid box at her bedside. Thank God for the ineptitude of his mother’s servants. They’d not cleaned the room, other than to change the linens after removing the body. The box still stood beside the bed. He reached in and removed several packs of letters, neatly bound with ribbon.

Correspondence from St John, the egg-sucking rat. Each letter beginning, ‘Dearest Mother …’

Marcus marvelled at his brother’s ability to lie with a straight face and no tremor in the script from the laughter as he’d written those words. But St John had no doubt been asking for money, and that was never a laughing matter to him.

No bundle of letters from himself, he noticed. Not that the curt missives he was prone to send would have been cherished by the dowager.

Letters from the lawyers, arranging estate matters. She’d been well prepared to go when the time had come.

And, on the bottom, a small stack of letters on heavy, cream vellum.

Dearest Andrea,

It has been many years, nearly forty, since last we saw each other at Miss Farthing’s school, and I have thought of you often. I read of your marriage to the late duke, and of the births of your sons. At the time, I’d thought to send congratulations, but you can understand why this would have been unwise. Still, I thought of you, and kept you in my prayers, hoping you received the life you so richly deserved.

I write you now, hoping that you can help an old friend in a time of need. It is not for me that I write, but for the daughter of our mutual friend, Anthony. Miranda’s life has not been an easy one since the death of her mother, and her father’s subsequent troubles. She has no hope of making an appropriate match in the ordinary way.

I am led to believe that both your sons are, at this time, unmarried. Your eldest has not found another wife since the death in childbirth of the duchess some ten years past. I know how important the succession must be to you. And we both know how accidents can occur, especially to active young men, as I’m sure your sons are.

So, perhaps the matchmaking of a pair of old school friends might solve both the problems and see young Miranda and one of your sons settled.

I await your answer in hope,

Cecily Dawson

An odd letter, he thought. Not impossible to call on an old school friend for help, but rather unusual if there had been no word in forty years. He turned to the second in the stack.

Andrea,

I still await your answer concerning the matter of Lady Miranda Grey. I do not wish to come down to Devon and settle this face to face, but will if I must. Please respond.

Awaiting your answer,

Cecily Dawson

He arched an eyebrow. Stranger still. He turned to the third letter.

Andrea,

Thank you for your brief answer of the fourteenth, but I am afraid it will not suffice. If you fear that the girl is unchaste, please understand that she is more innocent in the ways of the bedroom than either of us was

at her age. And I wish her to remain so until she can make a match suitable to her station. Whatever happened to her father, young Miranda is not to blame for it. But she is poor as a church mouse and beset with offers of things other than marriage. I want to see her safely away from here before disaster strikes. If not your sons, then perhaps another eligible gentleman in your vicinity. Could you arrange an introduction for her? Shepherd her through your social circle? Any assistance would be greatly appreciated.

Yours in gratitude,

Cecily

He turned to the last letter in the stack.

Andrea,

I am sorry to hear of your failing health, but will not accept it as excuse for your denial of aid. If you are to go to meet our Maker any time soon, ask him if he heard my forty years of pleadings for justice to be done between us. I can forgive the ills you’ve caused me, but you also deserve a portion of blame for the sorry life this child has led. Rescue her now. Set her back up to the station she deserves and I’ll pray for your soul. Turn your back again and I’ll bring the girl to Devon myself to explain the circumstances to your family at the funeral.

Cecily Dawson

He sat back on the bed, staring at the letters in confusion.

Blackmail. And, knowing his mother, it was a case of chickens come home to roost. If she had been without guilt, she’d have destroyed the letters and he’d have known nothing about it. What could his mother have done to set her immortal soul in jeopardy? To make her so hated that an old friend would pray for her damnation?

Any number of things, he thought grimly, if this Cecily woman stood between her and a goal. A man, perhaps? His father, he hoped. It would make the comments about the succession fall into place. His mother had been more than conscious of the family honour and its place in history. The need for a legitimate heir.

And the need to keep secret things secret.

He had been, too, at one time, before bitter experience had lifted the scales from his eyes. Some families were so corrupt it was better to let them die without issue. Some honour did not deserve to be protected. Some secrets were better exposed to the light. It relieved them of their power to taint their surroundings and destroy the lives of those around them.

And what fresh shame did this girl have, that his family was responsible for? St John, most likely. Carrying another by-blow, to be shuffled quietly into the family deck.

He frowned. But that couldn’t be right. The letters spoke of old crimes. And when he’d come on the girl and St John together, there had been no sense of conspiracy. She’d seemed a complete stranger to him and to this house. Lost in her surroundings.

She was not a pretty girl, certainly. But he’d not seen her at her best. Her long dark hair was falling from its pins, bedraggled and wet. The gown she’d worn had never been fashionable and being soaked in the storm had made it even more shapeless. It clung to her tall, bony frame the way that the hair stuck to the sharp contours of her face. Everything about her was hard: the lines of her face and body, the set of her mouth, the look in her eyes.

He smiled. A woman after his own heart. Maybe they would do well together, after all.

She looked around in despair. So this was to be her new home. Not this room, she hoped. It was grand enough for a duchess.

Precisely why she did not belong in it.

She forced that thought out of her mind.

‘This is the life you belong to, not the life you’ve lived so far. The past is an aberration. The future is merely a return to the correct path.’

All right. She had better take Cici’s words to heart. Repeat them as often as necessary until they became the truth.

Of course, if this was the life she was meant to have, then dust and cobwebs were an inherent part of her destiny. She’d hoped, when she finally got to enjoy the comforts of a great house, she would not be expected to clean it first. This room had not been aired in years. It would take a stout ladder to get up to the sconces to scrub off the tarnish and the grime, and to the top of the undusted mantelpiece. Hell and damnation upon the head of the man who thought that high ceilings lent majesty to a room.

She pulled back the dusty curtains on the window to peer into the rain-streaked night. This might be the front of the house, and those lumps below could be the view of a formal garden. No doubt gone to seed like everything else.

Was her new husband poor, that his estate had faded so?

Cici had thought not. ‘Rich enough to waste money on whores,’ she’d said. But then, she’d described the dowager as a spider at the centre of a great web. Miranda hadn’t expected to come and find the web empty.

Cici would have been overjoyed, she was sure. The weak part of the plan had always been the co-operation of the son. The dowager could be forced, but how would she gain the cooperation of the son without revealing all? Cici had hoped that one or the other of the two men was so hopelessly under the thumb of his mother as to agree without question when a suitable woman was put before him. But she’d had her doubts. If the sons were in their mother’s control, they’d have been married already.

To stumble into complete ruin was more good fortune than she could hope for.

She smothered her rising guilt. The duke had been right. She’d achieved her purpose and should derive some pleasure from it. She was about to become the lady to a very great, and very dirty, estate. She was about to marry a duke, the prize of every young girl of the ton. And have his heir.

She sat down on the edge of the bed. That was the crux of the problem. To have the heirs, she would have to become much more familiar with the Duke of Haughleigh than she would like. She was going to have to climb in the bed of that intimidating man and.

Lie very still and think of something else, she supposed. Cici had assured her that there were many types of men. And that the side they showed in the drawing room was not what she might see in the bedroom. She hoped not, or he’d spend the night interrogating her and tapping his foot when things did not go as fast as he’d hoped. She imagined him, standing over her on breakfast of their second wedded day, demanding to know why she wasn’t increasing.

‘Unfair. Unfair,’ Cici remonstrated in her head. ‘How can you claim to know a man you just met? Give him a chance.’

All right. A chance. And he had offered for her, when he’d realised her circumstances. He could have left her to ruin. If he could get over his initial anger at being trapped into a union, he might make a fine husband. She would try to make a decent wife.

And in a house as large as this, they might make do quite well without seeing each other. There was certainly enough space.

A soft knock sounded at the door. ‘Lady Miranda? His Lordship sent me up to do for you.’ A mob-capped head poked around the corner of the slightly opened door. ‘May I come in, ma’am?’

‘Yes, please.’

‘I’m Polly, ma’am. Not much of a lady’s maid, I’m afraid. There’s not been any call for it. The dowager’s woman went back to her people after the funeral.’

‘Well, it’s been a long time since I’ve had a lady’s maid, Polly, so we’ll just have to muddle through this together.’

The girl smiled and entered, carrying a tray with a teapot and a light supper. She set it down on a small table by the window. ‘Lord St John thought you’d be happier eating up here, ma’am. Supper in these parts is somewhat irregular.’

‘Irregular?’ As in, eaten seldom? Eaten at irregular times? Was the food strange in some way?

She glanced down at the meal, which consisted of a runny stew and a crust of dry bread. Certainly not what she’d expected. Too close to the poor meals she was used to. She tasted.

But not as well prepared.

‘The house is still finding its way after her Grace’s death.’ The maid bowed her head in a second’s reverent silence.

‘And what was the pattern before?’

‘Her Grace would mostly take a tray in her room, of the evenings.’

‘And her sons?’

‘Weren’t here, ma’am. Lord St John was mostly up in London. And his Grace was on the continent. Paris and such. He din’t come back ‘til just before his mother died, to make peace. And Lord St John almost missed the funeral.’

It was just as well that she was disgraced, she thought. It didn’t sound like either of the men would have had her because of the gentle pleadings of their mother.

‘When will we be expecting the rest of your things, ma’am?’ Polly was shaking the wrinkles out of a rather forlorn evening gown, surprised at having reached the bottom of the valise so soon. There was no good way to explain that the maid had seen the sum total of her trousseau: two day dresses, a gown and the travelling dress drying on a rack in the corner, supplemented by a pair of limp fichus, worn gloves and darned stockings.

‘I’m afraid there aren’t any more things, Polly. There was a problem on the coach,’ she lied. ‘There was a trunk, but it didn’t make the trip with me. The men accidentally left it behind, and I fear it is stolen by now.’

‘Perhaps not, ma’am,’ Polly replied. ‘Next time his Grace goes into the village, he can enquire after it. They’ll send it on once they have the direction.’

Miranda could guess the response she’d receive if she asked him to inquire after her mythical wardrobe. He would no doubt give her some kind of a household allowance. She’d counted on the fact. Perhaps his powers of observation weren’t sharp and she could begin making small purchases from it to supplement her clothing. She turned back to the topic at hand.

‘And was her Grace ill for long before her death?’

‘Yes, ma’am. She spent the last two months in her room. We all saw it coming.’

And shirked their duties because no one was there to scold them into action. By the look of the house, his Grace had not taken up the running of the house after the funeral. ‘And now that his Grace is in charge of things,’ she asked carefully, ‘what kind of a master is he?’

‘Don’t rightly know, ma’am. He tends to the lands and leaves the running of the house to itself. Some nights he eats with the tenants. Some nights he eats in the village. Some nights he don’t eat at all. There’s not been much done with the tenants’ houses and the upkeep since he’s been away, and I think he’s feelin’ a bit guilty. And there’s no telling what Lord St John is up to.’ She grinned, as though it was a point of pride in the household. ‘Young Lord St John is quite the man for a pretty face.’

‘Well, yes. Hmm.’ The last thing she needed. But he’d been pleasant to her and very helpful.

‘He was the one that suggested we put you up here, even though the room hasn’t been used much. Thought the duke’d want you up here eventually.’

‘And why would that be?’

Polly stuck a thumb in the direction of the door on the south wall. ‘It’s more handy, like. This was his late duchess’s room, although that goes back to well before my time.’

‘H-how long ago would that be, Polly?’ She glanced towards the bed, uncomfortable with the idea of sleeping on someone’s deathbed, no matter how grand it might appear.

‘Over ten years, ma’am.’ Polly saw the look in her eyes and grinned. ‘We’ve changed the linen since, I’m sure.’

‘Of course,’ she said, shaking herself for being a goose. ‘And her Grace died …?’

‘In childbed, ma’am. His Grace was quite broken up about it, and swore he’d leave the house to rot on its foundation before marrying again. He’s been on the continent most of the last ten years. Stops back once or twice a year to check on the estate, but that is all.’

Miranda leaned back in her chair and gripped the arms. The picture Cici had painted for her was of a man who had grieved, but was ready to marry again. And he hadn’t expected her. Hadn’t wanted her. Had only agreed to a meeting to humour his dying mother.

No wonder he had flown into a rage.

She should set him free of any obligation towards her. Perhaps he could lend her her coach fare back to London. Prospects were black, but certainly not as bad as attaching herself to an unwilling husband.

Don’t let an attack of missish nerves turn you from your destiny. There is nothing here to return to, should you turn aside an opportunity in Devon.

Nothing but Cici, who had been like a mother to her for so many years, and her poor, dear father. They’d sacrificed what little they had left to give her this one chance at a match. She couldn’t disappoint them. And if she became a duchess, she could find a way to see them again.

If her husband allowed.

‘What’s to become of me?’ she whispered more to herself than to Polly.

The night passed slowly, and the storm continued to pound against the windows. The room was damp and the pitiful fire laid in the grate did nothing to relieve it. Polly gave up trying, after several attempts, to find a chambermaid to air and change the bedding or to do something to improve the draw of the chimney. She returned with instructions from his Grace that, for the sake of propriety, Miranda was to remain in her room with the door locked until morning, when someone would come to fetch her to the chapel for her wedding. She carefully locked the door behind Polly, trying to imagine what dangers lay without that she must guard against. Surely, now that the damage was done, her honour was no longer at risk. Did wild dogs roam the corridor at night, that she needed to bar the door?

The only danger she feared was not likely to enter through the main door of her room. She glared across at the connecting door that led to the rooms of her future husband. If he wished to enter, he had easy access to her.

And the way to rescue or escape, should she need it, was blocked. The hairs on the back of her neck rose. She tiptoed across the room and laid her hand against the wood panel of the connecting door, leaning her head close to listen for noises from the other side. There was a muffled oath, a rustling, and nothing more. Yet.

She shook her head. She was being ridiculous. If he wanted her, there was no rush. She would legally belong to him in twenty-four hours. It was highly unlikely that he was planning to storm into her room tonight and take her.

She laid her hand on the doorknob. It would be locked, of course. She was being foolish. Her future husband had revealed nothing that indicated a desire for her now, or at any time in the future. He’d seemed more put out than lecherous at the thought of imminent matrimony and the accompanying sexual relations.

The doorknob turned in her hand and she opened it a crack before shutting it swiftly and turning to lean against it.

All right. The idea was not so outlandish after all. The door to the hall was locked against intruders and the way was clear for a visit from the man who would be her lord and master. She was helpless to prevent it.

And she was acting like she’d wasted her life on Minerva novels, or living some bad play with a lothario duke and a fainting virgin. If he’d been planning seduction, he’d had ample opportunity. If there were any real danger, she could call upon St John for help.

But, just in case, she edged the delicate gold-legged chair from the vanity under the doorknob of the connecting room. Remembering the duke, the width of his shoulders, and the boundless depths of his temper, she slid the vanity table to join the chair in blocking the doorway. Then she climbed back in the bed, pulled the covers up to her chin and stared sleeplessly up towards the canopy.

Marcus woke with a start, feeling the cold sweat rolling from his body and listening to the pounding of his heart, which slowed only slightly now that he was awake and recognised his surroundings.

Almost ten years without nightmares, since he’d stayed so far away from the place that had been their source. He’d been convinced that they would return as soon as he passed over the threshold. He’d lain awake, waiting for them on the first night and the second. And there had been nothing.

He’d thought, after his mother’s funeral, they would return. Night after night of feeling the dirt hitting his face and struggling for breath. Or beating against the closed coffin lid, while the earth echoed against the other side of it. Certainly, watching as they lowered his mother into the ground would bring back the dreams of smothering, the nightmares of premature burial that this house always held for him.

But there had been nothing but peaceful sleep in the last two months. And he’d lulled himself with the idea that he was free. At least as free as was possible, given the responsibilities of the title and land. Nothing to fear any more, and time to get about the business that he’d been avoiding for so long, of being a duke and steward of the land.

And now the dreams were back as strong as ever. It had been water this time. Probably echoes of the storm outside. Waves and waves of it, crashing into his room, dragging him under. Pressing against his lungs until he was forced to take the last liquid breath that would end his life.

He’d woken with a start. Some small sound had broken through the dream and now he lay in bed as his heart slowed, listening for a repetition.

The communicating door opened a crack, and a beam of light shot into his room, before the door was hastily closed with a small click that echoed in the silence.

He smothered a laugh. His betrothed, awake and creeping around the room, had brought him out of the dream that she was the probable cause of. He considered calling out to her that he was having a nightmare, and asking for comfort like a little boy. How mad would she think him then?

Not mad, perhaps. It wasn’t fear of his madness that made her check the door. Foolish of him not to lock it himself and set her mind at rest. But it had been a long time since he’d been over that threshold, and he’d ignored it for so long that he’d almost forgotten it was there.

He smiled towards his future bride through the darkness.

I know you are there. Just the other side of the door. If I listen, I can hear the sound of your breathing. Come into my room, darling. Come closer. Closer. Closer still. You’re afraid, aren’t you? Afraid of the future? Well, hell, so am I. But I know a way we can pass the hours until dawn. Honour and virtue and obligation be damned for just a night, just one night.

Too late, he decided, as he heard the sound of something heavy being dragged across the carpet to lean in front of the unlocked door. He stared up at the canopy of his bed. She was, no doubt, a most honourable and virtuous young lady who would make a fine wife. The thought was immeasurably depressing.

Chapter Four

The vicar was shaking his head dourly and Marcus slipped the explanatory letter off the blotter and towards him. ‘As you can see, I was just writing to you to invite you to the house so we could resolve this situation.’ His lips thinned as he fought to contain the rest of the thought.

Of course I needn’t have bothered. You hitched up the carriage and were on your way here as soon as the sun rose. Come to see the storm damage, have you, vicar? Meddling old fool. You’ve come to see the girl and you’re hoping for the worst.

The vicar looked sympathetic, but couldn’t disguise the sanctimonious smile as he spoke. ‘Most unfortunate. A most unfortunate turn of events. Of course, you realise what your duty is in this situation, to prevent talk in the village and to protect the young lady’s reputation.’

A duty that could have been prevented yesterday, if you actually cared a jot for the girl or for silencing talk.

‘Yes,’ he responded mildly. ‘I discussed it with Miranda yesterday and we are in agreement. It only remains to arrange the ceremony.’

The vicar nodded. ‘Your mother would have been most pleased.’

‘Would she, now?’ His eyes narrowed.

‘Hmm, yes. She mentioned as much on my last visit to her.’

‘Mentioned Miranda, did she?’

He nodded again. ‘Yes. She said that a match between you was in the offing. It was her fondest hope—’

‘Damn.’

‘Your Grace. There’s no need—’

‘This was all neatly arranged, wasn’t it? My mother’s hand from beyond the grave, shoving that poor girl down the road to ruin, and you and your wife looking the other way while it happened.’ He leaned forward and the vicar leaned back.

‘Your Grace, I hardly think—’

‘You hardly do, that’s for certain. Suppose I am as bad as my mother made me out to be? Then you would have thrown the girl’s honour away in the hope that I would agree to this madness. Suppose I had been from home when she arrived? Suppose it had been just St John here to greet her? Do you honestly think he would be so agreeable?’ He was on the verge of shouting again. He paused to gain control and his next words were a cold and contemptuous whisper. ‘Or would you have brushed that circumstance under the rug and rushed her back out of town, instead of trumpeting the girl’s location around the village so that everyone would know and my obligation would be clear?’

‘That does not signify. Fortunately, we have only the situation at hand to deal with.’

‘Which leaves me married to a stranger chosen by my mother.’

He was nodding again, but without certainty. ‘Hmm, well … under the circumstances it would be best to act expediently. The banns—’

‘Are far from expedient, as I remember. We dispensed with them the last time. A special licence.’

‘If you send to London today, then perhaps by next week …’

‘And I suppose you will spirit the girl away to your house for a week, until the paperwork catches up with the plotting. Really, Reverend, you and my mother should have planned this better. Perhaps you should have forged my name on the application a month ago and we could have settled this today. You needn’t have involved me in the decision at all.’ He thought for a moment and stared coldly at the priest. ‘This is how we will proceed. You will perform the ceremony today, and I will go off to London tomorrow for the licence.’

‘But that would be highly improper.’

‘But it would ensure I need never see your face in my house again, and that suits me well. If you cared for impropriety, you should have seen to it yesterday, when you met Miranda on her way here. When I come back with the licence I will have a servant bring it to you and you can fill in whatever dates you choose and sign the bloody thing. But this morning you will see the young lady and myself married before the eyes of God in the family chapel.’

His head was shaking now in obvious disapproval. ‘Hmm. Well, that would hardly be legitimate.’

‘Not legal, perhaps, but certainly moral. And morality is what you are supposed to concern yourself with. If you don’t question the fact that you coerced me into taking her, then do not waste breath telling me my behaviour is improper. Open the prayer book and say the words, take yourself and your bullying harpy of a wife away from this house and leave me in peace. Now go to the chapel and prepare for the ceremony. Miranda and I will be there shortly.’

The vicar hemmed and harrumphed his way out of the study, not happy, but apparently willing to follow Marcus’s plan without further objections. A generous gratuity after the ceremony would go a long way towards smoothing any remaining ruffled feathers and soon the scandal of his new marriage would fade away as though there had been nothing unusual about it.

His mind was at rest on one point, at least. The interview with the vicar exonerated Miranda of any blame for the unusual and scandalous way she had appeared on his doorstep. She had hoped to make a match, but there was no evidence that she had tried to trap him by ruining herself. There was no reason to believe that she was anything other than what she appeared to be.

Unless she was dishonoured before she arrived at his home.

The letters from the mysterious Cecily said otherwise. They said she was innocent. But, of course, they would. No sane person would send a letter, claiming that the girl was a trollop but had a good heart. He struggled with the thought, trying to force it from his mind. He was well and truly bound to her by oath and honour, whatever the condition of her reputation.

But not by law. Until his name was on the licence he was not tying a knot that could not be untied, should the truth come to light soon. He would watch the girl and find what he could of the truth before it was too late. And he would protect her while she was in his home; make sure he was not worsening an already bad situation. He rang the bell for Wilkins and demanded that he summon St John to the study.

After a short time, his brother lounged into the room with the same contempt and insolence that he always displayed when they were alone together. ‘As always your servant, your Grace.’

‘Spare me the false subservience for once, St John.’

St John smirked at him. ‘You don’t appreciate me when I do my utmost to show respect for you, Haughleigh. It is, alas, so hard to please the peer.’

‘As you make a point of telling me, whenever we speak. You can call a truce for just one day. Today you will grant me the honour due a duke, and the master of this house.’ He was close to shouting again. His plan to appeal to him as a brother was scuttled before he had a chance to act on it. To hell with his quick temper and St John’s ability to reduce him to a towering rage without expending any energy.

‘Very well, Marcus.’ The name sounded as false and contemptible as his title always did when it came from his brother’s lips. ‘A truce, but only for a day. Consider it my wedding gift to you.’

‘It is about the wedding that I meant to talk to you, St John.’

‘Oh, really?’ There was the insolent quirk of the eyebrows that he had grown to loathe. ‘Is there anything you need advice on? I’d assumed that the vicar would give you the speech on the duties of the husband. Or that perhaps you recalled some of them, after Bethany. But, remembering your last marriage, I could see where you might come to me for advice.’

Marcus’s fist slammed down on the desk as though he had no control. ‘How dare you, St John? Damn you for speaking of Bethany, today of all days.’

‘Why not, Marcus? She is never far from my mind. Just because you wish to forget her does not mean that I will.’

He flexed his hands and pushed away the image of them closing on St John’s windpipe, and then placed them carefully on the blotter. ‘You promised a truce and I see how quickly you forget it. Let us pretend for a moment, St John, that you have any honour left as it pertains to this house.’

‘Very well, brother. One last game of “Let’s Pretend”, as we played when we were little. And what are we pretending, pray tell?’

‘That you are planning to go willingly from this house, today, and that it will not be necessary for me to have the servants evict you.’

‘Go? From this house? Why ever would I do that, Marcus?’

‘Because you hate it here as much as I do. And you hate me. There. There are two good reasons. I must remain here to face what memories there are. As you are quick to point out to me, whenever we are alone, I am the Duke of Haughleigh. And now I am to be married, and chances are good that I will soon have a son to inherit. There is no reason for you to wait in the house for me to break my neck on the stairs and leave you the title and the entail. I am certain that, should the happy accident you are waiting for occur before a son arrives, my wife will notify you and you can return.’

‘You are right, Marcus. I do hate you, and this house. But I have grown quite fond of Miranda.’

‘In the twelve hours you have known her.’

‘I have spent more time with her during those hours than you have, Marcus. While you were busy playing lord of the manor and issuing commands, I was stealing a march. And now, I should find it quite hard to part myself from my dear little sister, for that is how I view her.’ The smile on his face was deceptively innocent. Marcus knew it well.

‘You will view her, if at all, from a distance.’ Marcus reached into the desk drawer and removed a leather purse that clanked with gold when he threw it out on to the desktop. ‘You will go today, and take my purse with you. You need not even stop in your room to pack, for Wilkins is already taking care of that. Your things will be on the way to the inn within the hour.’

‘You think of everything, don’t you, Marcus? Except, of course, what you will do if I refuse to accede to your command.’

‘Oh, St John, I’ve thought of that as well.’

‘Really?’

‘Yes. You can leave for the inn immediately, and from there to points distant. Or you can leave feet foremost for a position slightly to the left of Mother. The view from the spot I plan for you is exceptional, although you will no longer be able to enjoy it.’

‘Fratricide? You have become quite the man of action in the ten years we’ve been parted, Marcus.’

‘Or a duel, if you have the nerve. The results will be the same, I assure you. I can only guess how you’ve spent the intervening years, but I’ve studied with the best fencing masters in Italy, and am a crack shot. I’ve allowed you a period of mourning and have made what efforts I could to mend the breach between us and put the past to rest. It has been an abject failure. After today, you are no longer welcome in my home, St John. If you do not leave willingly, I will remove you myself.’

‘Afraid, Marcus?’

‘Of you? Certainly not.’ He shifted in his chair, trying to disguise the tension building within him.

‘Of the past coming back to haunt you, I think.’

‘Not afraid, St John. But not the naïve young man I once was. There is no place for you here. What is your decision?’

St John leaned an indolent hand forward and pulled the purse to himself. ‘How could I refuse your generosity, Marcus? I will say hello to all the old gang in London, and buy them a drink in honour of you and your lovely new wife.’

Marcus felt his muscles relax and tried not to let his breath expel in a relieved puff. ‘You have chosen wisely, St John.’

Miranda waited politely as Mrs Winslow and Polly examined the gown. ‘But it’s grey.’ Mrs Winslow’s disappointment was obvious.

‘It seemed a serviceable choice at the time.’ Miranda’s excuse was as limp as the lace that trimmed the gown.

‘My dear, common sense is all well and good, but this is your wedding day. Have you nothing more appropriate? This gown appears more suitable—’

‘For mourning?’ Miranda supplied. ‘Well, yes. My own dear mother …’

Had been dead for thirteen years. But what Mrs Winslow did not know would not hurt her. And if the death seemed more recent, it explained the dress. The gown in question had, in fact, been Cici’s mourning dress, purchased fifteen years’ distant, after the death of a Spanish count. While full mourning black might have been more appropriate, Cici had chosen dove grey silk, not wanting to appear unavailable for long. It had taken some doing to shorten the bodice and lengthen the skirt to fit Miranda, but they’d done a creditable job by adding a ruffle at the hem.

‘Your mother? You poor dear. But you’re well out of mourning now?’

‘Of course. But I’ve had little time to buy new things.’ Or money, she added to herself.

‘Well, now that the duke will be looking after you, I’m sure that things will be looking up. And for now, this must do.’ Mrs Winslow looked at her curiously. ‘Before your mother died … did she …?’ She took a deep breath. ‘There are things that every young woman must know. Before she marries. Certain facts that will make the first night less of a … a shock.’

Miranda bit her lip. It was better not to reveal how much she knew on the subject of marital relations. Cici’s lectures had been informative, if unorthodox, and had given her an unladylike command of the details. ‘Thank you for your concern, Mrs Winslow.’

‘Are you aware … there are differences in the male and the female …?’

‘Yes,’ she answered a little too quickly. ‘I helped … nursing … charity work.’ Much could be explained by charity work, she hoped.

‘Then you have seen …’ Mrs Winslow took a nervous sip of tea.

‘Yes.’

‘Good. Well, not good, precisely. But at least you will not be surprised.’ She rushed on, ‘And the two genders fit together where there are differences, and the man plants a seed and that is where babies come from. Do you understand?’

Cici had made it clear enough, but she doubted that Mrs Winslow’s description was of much use to the uninitiated. ‘I …’

‘Never mind,’ the woman continued. ‘I dare say the duke knows well enough how to proceed. You must trust him in all things. However, the duke … is a very—’ words failed her again ‘—vigorous man.’

‘Vigorous?’

‘In his prime. Robust. And the men in his family are reported to have healthy appetites. Too healthy, some might say.’ She sniffed in disapproval.

Miranda looked at the vicar’s wife with what she hoped was an appropriately confused expression, and did not have to feign the blush colouring her cheeks.

‘And the baby that his first wife was delivering when she died was said to be exceptionally large. A difficult birth. He will, of course, insist on an heir. But if his demands seem excessive after the birth of the first child … many women find … a megrim, perhaps. A small lie is not a major sin when it gains a tired woman an occasional night of peace.’

Miranda stood at the back of the chapel, waiting for the man who was to seal her destiny. When the knock had sounded at her door, she’d expected the duke, but had been surprised to see St John, holding a small bouquet out to her and offering to accompany her to the chapel. The gown she’d finally chosen for the wedding was not the silk, but her best day dress, and, if he thought to make a comment on the state of it, it didn’t show. It had looked much better in the firelight as she’d altered it. Here in Devon, in the light of day, the sorriness of it was plainly apparent to anyone that cared to look. The hem of Cici’s green cotton gown had been let down several inches to accommodate her long legs, and the crease of the old hem was clearly visible behind the unusually placed strip of lace meant to conceal it. The ruffles, cut from the excess fabric of the bodice when she’d taken it in, and added to the ends of the sleeves, did not quite match, and the scrap of wilted lace at their ends made the whole affair look not so much cheerful as pathetic.

‘There now, mouse. Don’t look so glum, although I could see where a long talk with the vicar’s wife might not put you in the mood to smile. Did she explain to you your wifely duties?’

She blushed at St John’s boldness. ‘After a fashion. And then she quizzed me about my parents, and about the last twenty-four hours. And she assured me that whatever you might have done to me, if I felt the need to flee, they would take me in, and ask no questions.’

His laugh rang against the vaulted ceiling and the vicar and his wife looked back in disapproval. ‘And God does not strike them down for their lies when they say they wouldn’t question you. At least my brother and I make no bones about our wicked ways. They cloak their desire to hear the salacious story of your seduction in an offer of shelter.’

‘My what?’

‘They hope for the worst, my dear. If you were to burst into tears at the altar and plead for rescue, you will fulfil all of their wildest dreams and surmises.’

‘St John.’ She frowned her disapproval.

‘Or better yet, you could fall weeping to my arms and let me carry you away from this place, as my brother rages. I would be delighted to oblige.’

‘As if that would not make my reputation.’

‘Ah, but what a reputation. To be seduced away from your wedding by the duke’s roguishly handsome younger brother and carried off somewhere. Oh, but I see I’m upsetting you.’ He pointed up to the window above the altar, where the bleeding head of St John the Baptist rested in stained glass. ‘I don’t know what my mother was thinking of, naming me for a saint. If it was to imbue me with piousness and virtue, it didn’t work.’

‘Was the window commissioned in your honour, then?’

‘Can you not see the resemblance?’ He tilted his head to the side, tongue lolling out of his mouth and eyes rolled to show the whites. And, despite herself, she laughed.

‘No, it’s an old family name, and the window was commissioned after some particularly reprehensible St John before me. Probably lost his head over a woman, the poor soul.’ He touched his blond hair and admitted, ‘There is a slight resemblance, though. Most of the art in this room was made to look like family. It is my brother who looks more like my mother’s indiscretion than my father’s first child.’

‘I don’t think so,’ she remarked, pointing at a marble statue. ‘That scowling martyr in the corner could well be him. See the profile?’

St John laughed. ‘No, my brother was never named from the bible. He was named for a Roman dictator. Quite fitting, really.’