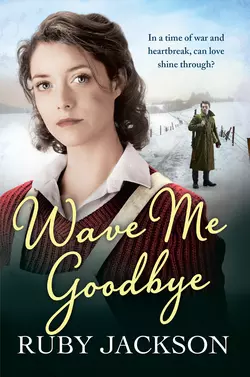

Wave Me Goodbye

Ruby Jackson

A compelling story of tragedy and triumph in WWII -the second in a series of books featuring four young women whose lives will be forever changed by the war. Perfect for fans of Katie Flynn and Annie Groves.When war is declared, four plucky girls from Dartford – Grace, Sally, Rose and Daisy – are keen to do their bit on the Home Front.For orphan Grace, it’s a chance to start afresh. She’s always has a soft spot for Sam Petrie, brother of Daisy and Rose, but realising that he is in love with their friend Sally, she puts her own feelings aside, and signs up for life as a Land Girl.Mucking out and early morning milking come as a big shock and life is harder than she expected. But Grace is nothing if not determined and though their lives will never be the same again, the four girls know they will always have each other – no matter what the war throws at them…

Copyright (#uc6202466-c7f9-5b40-b7a6-590c3cd4dc7f)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 77–85 Fulham Palace Road Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2013

Copyright © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2013

Cover photographs © Colin Thomas (Woman); Jonathan Ring (soldier); Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com) (road) Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2013

Ruby Jackson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007506262

Ebook Edition © November 2013 ISBN: 9780007506286

Version: 2014-12-17

Contents

Cover (#u552de468-908c-5427-a068-5655692af50d)

Title Page (#ud9f6d2b9-e157-5f08-9133-c0c6296d67c4)

Copyright

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Read on for an exclusive extract of On A Wing And A Prayer, coming in spring 2015

Find out how it all started for Daisy, Rose, Sally and Grace in Churchill’s Angels - available now. Read on for an exciting extract …

Keep Reading

Acknowledgements

About Ruby Jackson

Also by Ruby Jackson

About the Publisher

ONE (#uc6202466-c7f9-5b40-b7a6-590c3cd4dc7f)

Kent, February 1940

She had been right to do it, to pack up her few personal belongings and go without a word to anyone, even to those who had been so kind to her for many years. She regretted that: not the kindness, of course, but the manner of her leaving. How could she explain to them that she could no longer bear her present existence, the hostility of her own sister, the uncomfortable, unwelcoming damp little house that she and, she supposed, Megan called home? Even her job in the office of the Vickers munitions factory was unfulfilling. All that had brightened her life had been the friendship of the Brewer and Petrie families, the small garden that she and her friends had created, and daydreams of Sam. Winter frosts had killed the garden that had given her such pleasure, but Sam, who had seen war coming and had enlisted long before September 1939, was with his regiment – somewhere. Useless to daydream about Sam, though, not because she had no idea where he was or what was happening to him but because he loved Sally Brewer.

It was easy to picture Sally, with her long black hair and her glorious blue eyes. Sally, an aspiring actress, was almost as tall as any one of the three Petrie sons, and a perfect foil for Sam’s Nordic blondness. How could she, plain Grace Paterson, who did not even know who her parents were, be attractive to a man like Sam? Oh, he had been kind to her when she was a child but Sam, eldest in a large family, had been kind to everyone. What would he think of her when he heard some day that she had disappeared without a word?

Grace sobbed and buried her face in her pillow in case any of the other girls were to come in and hear her. Her conscience, however, kept pricking her and, eventually, she found that intolerable. You have to write, Grace, you owe them that much.

She got up, straightened the grey woollen blanket and thumped her lumpy pillow into shape. Right, I’m not going to lie here whimpering, she decided. I will write to everyone and then, when it’s off my mind, I’m going to try to be the best land girl in the whole of the Land Army.

She picked up the notebook she had bought in nearby Sevenoaks, and moved down the room between the long rows of iron bedsteads, each with its warm grey blankets, and here and there an old, much-loved toy brought from home for comfort. She reached the desk where, for once, no other girl was sitting and examined the lined jotter pages. Immediately, Grace worried that she ought to have spent a little more of her hard-earned money on buying proper writing paper. She shook her head and promised herself that she would do just that when her four weeks of training were completed and she had moved on to a working farm.

Mrs Petrie and Mrs Brewer won’t mind, she told herself.

When had she first met them? More than half a lifetime ago but, since she was not yet twenty, half a lifetime wasn’t long. Grace sighed. Ten, eleven Christmases spent at the home of her friend Sally Brewer. Ten birthdays either with the Brewers or with the Petries. But when she thought of the Petrie family, it was not kind, comfortable Mrs Petrie or even her school friends, the twins, Rose and Daisy, who immediately came vividly to life in her mind, but Sam. Sam, who, for all she knew, might be dead.

No, he could not be dead. God would not be so cruel. She closed her eyes and immediately saw him – tall, blond, blue-eyed Sam – chasing the bullies who had pushed her down in the playground. He had picked her up, dusted her down and handed her over to his twin sisters.

So many kindnesses, and she had repaid them by slinking away, like a cat in the night, without a word of explanation or thanks. Again, Grace turned her attention to the notebook and began to write:

Dear Mrs Petrie,

I’ve joined the Women’s Land Army and I’m learning all about cows.

That unpromising beginning was torn up. She started again:

Dear Mrs Petrie,

I am very sorry for not telling you that I applied to join the Women’s Land Army. I thought it would take some time and I could tell you but I went in and there were lots of women and eventually this posh lady asked me my age and did my mother know. I said I didn’t have a mother. You do know it’s jolly hard work? she said after she’d been thinking. I’ve never heard anyone say, jolly hard. Another lady said, See the doctor now. He was in the next room and I was a bit scared as I haven’t ever been seen by a doctor, not ever been ill, proper ill. The doctor looked at me and said, Have you ever been ill, or been in hospital? I wasn’t sure but I don’t think I have and so I said, No, sir, and he said, Why on earth do you want to join? It’s bloody awful work.

Grace stopped and thought hard. Was her simple little tale interesting? Would Mrs Petrie think it odd that the doctor had only asked a few questions and then told her that she would do, whatever that meant, and then had added something about being sure to drink milk?

And how could she explain why she had wanted to join, even knowing that it was ‘bloody awful work’?

It was working in the garden, growing the sprouts and things. It’s hard to explain but, although it was really hard work, I enjoyed it. I felt

She could not explain the pleasure or the satisfaction that growing things had given her and so that effort at a letter ended in the wastebasket, too. She tried to write to Mrs Brewer and four attempts ended beside the others. Grace stared in despair at the wall in front of her but, in her head, saw only the waiting room of the doctor’s surgery in Dartford.

There were several girls and women there, and from their clothes and, in some instances, their voices, Grace realised that they came from what Mr Brewer called ‘all walks of life’, though so far no one had her accent, which, Megan, her half-sister, always said was half-Scot, half-Kent. Grace waited quietly, head down, until she was called.

The doctor was quite old: he had to be older than either Mr Brewer or Mr Petrie and they would soon be fifty. Had all the young doctors been called up?

‘Some simple questions, first, Miss Paterson. Why do you want to join the Land Army?’

‘I like growing things.’

‘Any experience?’

‘I had a little vegetable garden.’

‘Splendid? Any illnesses?’

‘No, not real illness. Measles once.’ Grace had felt the words ‘in the convent’ forming on her lips. Why had she wanted to say that? She had never been in a convent, had she?

‘Height?’

Since the younger Petrie boys had tried stretching her every so often as they grew up, Grace knew exactly how tall she was, but behind her back she crossed her fingers against bad luck and added half an inch. ‘Five feet two and a half inches.’

He looked at her and she breathed in and tried to stretch her neck.

‘You’ll do,’ he said, heavy notes of doubt in his voice. ‘Shoe size?’

Stupid to fib here. ‘Four.’

‘Difficult. Best take all your old socks.’

Grace smiled. Surely that sounded positive, even if her feet were too small to be of any use to the war effort.

‘Do you have varicose veins?’

She hadn’t the slightest idea what a varicose vein was but said, ‘Of course not.’ Her reply seemed both to please and surprise the doctor, who was busily making notes as Grace waited in something approaching terror for the physical examination.

The doctor closed the folder. ‘Thank you, Miss Paterson. Wait outside, please, and, Miss Paterson, be sure to drink all the milk they give you.’

No physical examination; he hadn’t even taken her pulse. If he were to take it now, he would feel it racing.

‘You’ll do. You’ll do.’ The loveliest words in the English language repeated themselves over and over in her head.

‘Still awake? Want some cocoa? We’re making it in the kitchen and they’ve left us some scones – with butter. Amazing how we’re able to squeeze more food in at bedtime just a few hours after a three-course tea.’

One of Grace’s roommates, Olive Turner, was standing in the doorway, and the appetising smell of a freshly baked, and therefore hot, scone wafted across the room.

Grace rose in some relief. ‘It’s hard work and fresh air does it,’ she said. ‘That smells heavenly.’

‘And it’s mine,’ Olive laughed, and together they ran down the three flights of uncarpeted stairs to the kitchen, where several of the other girls were crowded round the long wooden table. A plate, piled high with scones, several little pots of raspberry jam, each with a land girl’s name on it, and each girl’s own rationed pat of butter, were clustered together in the centre of the table.

‘Home sweet home,’ said Olive, as she and Grace found empty chairs.

‘My home was never like this,’ said another girl, Betty Goode, as she bit into her scone.

The others laughed and Grace smiled but said nothing. The trainee land girls drank their hot cocoa and ate scones filled with farm butter and raspberry jam until their supervisor came in to remind them that cows would be waiting to be milked at five o’clock next morning. Groaning, the girls finished their supper, washed up, and made their way back upstairs to bed.

Grace washed and undressed as quickly as possible. The house was large but the third floor, where the girls were housed, was cold.

‘Beds are nice and warm, girls,’ their supervisor had said, ‘and I’m sorry I can’t get any heat up here but the summer class’ll be wishing it was colder; hotter than a glasshouse, this place gets.’

The land girls had rather liked the idea of being in a lovely warm glasshouse, especially now, in February, when icy winds found every chink in the walls or the roof. Some had even perfected the art of dressing and undressing under their covers, not for modesty but for comfort. Grace, having been brought up in an almost dilapidated old house with one working fireplace, was used to discomfort, and dressed and undressed with well-practised speed.

‘Will we ever be warm again, Grace? My feet are like ice.’ Olive, in the next bed, issued her usual nightly complaint.

‘Keep your socks on, stupid,’ the other girls called, but soon, exhausted by their long day of punishing chores, they slept.

Grace appreciated the warm, woollen, knee-length stockings that had been issued to her with the rest of her uniform. She was not quite so fond of the Aertex shirt; it somehow didn’t fit properly and she was glad that, for the present, most of it was hidden under her green issue jumper. She took great care of these clothes. Thanks to Sally’s mother, and Daisy’s, she had had something brand-new every birthday, even if it was a cardigan that had been knitted from wool that had been used previously. The cardigan was made for her and therefore it did not matter that the wool was old. Women like Mrs Brewer and Mrs Petrie had become experts at ‘Make Do and Mend’ long before the government posters had come out asking the people of Britain to be economical.

Loud groans emanated from every bed several hours later as the trainees were awakened by the large metal alarm clock that stood in a tin basin so that it would make even more of a racket as it told the world that it was already four a.m.

‘My God, why didn’t I join the army or become a nurse?’ This question was asked daily.

‘The army never sleeps and bedpans are a great reason for not nursing.’

‘Please, it’s bad enough having to get up before the damn cockerel without having to listen to all the moans.’

Grace smiled. She loved the life; she enjoyed being with women who were all about the same age. If all the farms she would work on during this beastly war were like this one, she saw no reason to complain.

The word she heard most often from the dairyman was ‘cleanliness’. He wanted the girls clean, their white aprons spotless, and he inspected every girl’s hands each time they were in the dairy. The work was hard. The first cow she had encountered had terrified her. This large, warm brown-and-white animal with such lovely eyes had suddenly glared at her as she tried milking it in the way that had been explained and then demonstrated, and had deliberately kicked over her pail, spilling the precious milk, which ran down the drain. The instructor had glared.

‘Try to keep hold of the milk, Paterson; there’s a war on and we need every drop.’

Now at the end of a week of learning how to milk, Grace felt quite secure in her ability. She could manage to wash the rear end of the cow and its udders before starting either hand or machine milking and the workspace was warm. Cleaning out the parlour after milking was not such a pleasant job. The water was always ice cold and the smell of cow waste was, to Grace, unpleasant.

‘Rubbish,’ announced George, the head dairyman, his Scottish accent giving the word a fierce emphasis, when some of the girls complained. ‘Nowt wrong with a good, clean farmyard smell. Too dainty by half, some of you.’

But if George was difficult to please, he was also patient and fair, and the girls enjoyed his crustiness.

Milking was done and the cows had to be taken out to fields close to the farmhouse. There was still no sign of new growth and so Grace and Olive Turner were assigned to fork hay into large feeding troughs, back-breaking work but warming.

‘Hope they’ve left us some breakfast,’ moaned Olive, as the rumbling in her empty stomach reminded her of the time.

‘Warden’ll make sure we eat.’

‘Happen you’re right, Grace, here at the training centre, but I’m worried about postings. I’ve heard ever so many stories about how mean some farmers are. All they want is cheap labour, and the less they have to give in return the better.’

Grace had also heard scare stories but preferred not to believe them. Farmers were people and there were different types of people: mean ones like her sister, Megan, and decent, generous ones like the Petries and the Brewers. ‘Everything will be fine, Olive. Now let’s finish this and get back to the house.’

‘Wouldn’t it be terrific if Wellington boots had fur linings?’ Olive – who had just stepped into something that smelled terrible, looked awful, and was very wet and cold – stood on one wellingtoned leg and looked down at the one caught tight in the mire.

Grace helped her pull her boot out and it came with a rather horrid slurping sound. It was quite common to lose boots in farm muck and to be forced to dance around on one leg while trying not to put the bootless foot down. ‘Best idea I ever heard, Olive, love. In the meantime, wear more socks.’

‘I don’t have many pairs, and not thick ones.’

‘I’m sure I can lend you some. Brighten up; it’ll soon be spring – daffodils, primroses, little lambs. Now cheer up and smell your breakfast.’

They had arrived at the kitchen door and the smell of sizzling sausages came out to welcome them.

‘I hope there’s enough porridge left for the pair of you, but there are three sausages and so you may have one and a half each in a fresh-baked roll. Luckily for you, I came to make myself a fresh pot of tea,’ said Miss Ryland, the manager of the hostel.

Grace and Olive washed their hands in the deep sink and sat down gratefully at the table with their plates of porridge.

‘Ambrosia,’ Olive said as she finished her bowl.

‘I never heard that word before. What’s it mean? I’d like to write it to my friend Daisy; she loves learning new words.’

Olive shrugged. ‘Dunno, really. Something special, I think. Just heard someone say it when something really tasted good.’

‘Ambrosia was a honey-flavoured food of the Greek gods, girls,’ said Miss Ryland. ‘And if it does for you two what it was supposed to do for the gods, you have years of cleaning out cowsheds ahead of you.’

The girls looked at her in astonishment.

‘Would you explain, Miss Ryland, please?’ Grace asked. ‘I don’t know about Olive, but I’ll happily clean cowsheds if it helps the war effort, but for how many years?’

‘Ambrosia promises immortality, Grace. You’ll live for ever, cleaning up cowpats.’

Olive looked as if she might burst into tears.

‘She’s joking,’ said Grace. ‘It’s only a story but, just in case, you’d better start knitting more warm socks.’

‘Enough chatter, finish your sausages and get on with your next cowshed.’

When they had finished the hearty breakfast, the land girls wrapped themselves up again and left the hostel.

‘What’s next?’ Olive was already shaking with cold. ‘When were we supposed to get the warm coats?’

‘I hope they’ll be sent to us here, but I think Miss Ryland is the type who won’t mind if we ask her about them.’ Grace looked at her companion, who was almost blue with cold. ‘You need to put on two jumpers, Olive, or at least a liberty bodice. Don’t you have one of those? If you don’t, I can let you have mine when we go back for our dinner.’ Grace remembered, all too clearly, how it felt not to have enough warm clothes. Her sister had not been the best provider, seeming to begrudge every penny that was spent on the little girl who, for reasons known only to her, Megan had promised to bring up.

‘I did have a nice liberty bodice,’ said Olive with a sneeze. ‘My mum said, “Take it with you and wear it over your vest,” but I’m not a child any more.’

‘No, you’re a young woman who’s catching a cold. Just as well it’s a lecture. You can warm up and put more clothes on before the sheep this afternoon. Come on.’

They hurried to the main building where, they were later told, a fascinating lecture on arable farming was in progress but, instead of being allowed to go in, they were yelled at for daring to enter wearing such filthy Wellingtons. ‘No one ever teach you to wash off mud before you enter a building?’

‘We did,’ began Grace, but she was given no chance to explain that the new mud had been acquired on their way to the classroom.

‘Never make excuses, and keep your eyes open for pumps. Now get out and get clean.’

They backed out as quickly and as gracefully as they could, washed off the mud and went back in.

Betty Goode was waiting for them, her round rosy face tense with anxiety. ‘You missed the first half of the lecture but I’ll share my notes. It was an absolute hoot. Did you get breakfast?’

‘Yes, thank you, Betty,’ said Grace, just as Olive sneezed loudly.

The two other girls looked at each other anxiously, over Betty’s head, and Grace made a swift decision, based on her ever-present memories of neglect. It was not just that Olive was sneezing but the girl was shivering and the entrance hall was quite warm.

‘I’m taking her back to Miss Ryland. If they call my name, tell them I’ll come as soon as I can.’

Olive protested feebly.

‘Come on, the rest of the day in bed with a hot-water bottle and you’ll shake it.’ She smiled. I’m doing for someone else what Rose and Daisyand Sally and their families have always done for me.

It was a lovely feeling, until she remembered that she had not contacted her friends. They’re not Megan; they’ll forgive me because they care about me.

She shepherded Olive back to the hostel, where she found Miss Ryland in her office. The manager looked up from the papers she had been reading and was visibly startled by the sight of two bedraggled land girls.

‘Why aren’t you two in class?’ Her usually calm and friendly voice was now quite icy in tone.

Olive sneezed loudly several times in quick succession; almost drowning out Grace’s explanation. ‘Olive’s unwell, Miss Ryland. She’s been sneezing and sniffling all morning and so I thought it was better to bring her back and to put her to bed for the afternoon.’

Miss Ryland’s well-defined and savagely plucked eyebrows seemed to rise up into her hairline. She got to her feet and stood surveying first the room and then the girls. Olive hung her head. But Grace, although as frightened as she had been as a child when confronted by her older sister, stood her ground.

‘And who, Miss Paterson, gave you the authority to decide who does or does not take an afternoon off?’

‘She’s not taking an afternoon off. I think she’s really sick.’

‘You’re a doctor. Silly me. I thought you were a land girl. You do know that there’s a war on and taking time off, without permission…? Or did you ask the lecturer for a pass?’

Olive began to cry. She was shaking. ‘Please, it’s all my fault, not Grace’s. I didn’t wear my liberty bodice.’

There was a stunned silence, eventually broken by Grace. ‘It’s not her fault. She’s too sick to make a sensible decision and I don’t think Mr Churchill would want her to—’

That was as far as she got.

Miss Ryland was looking at her as if she could not believe her eyes – or ears. ‘Enough, you insolent girl. How dare you consider yourself capable of deciding what Mr Churchill would or would not want?’ She turned. ‘As for you – Turner, is it? – return to the lecture room immediately.’

Olive turned and, without a word, ran from the room.

Grace waited. Long experience had taught her that to attempt an excuse, to say anything, would only make matters worse. Miss Ryland stood, looking down at the telephone on her desk. Was she expecting it to ring or did she mean to make a telephone call, to complain about Grace Paterson?

‘Neither of you is dressed for winter conditions,’ she said at last.

‘We haven’t got coats yet. I thought I could ask you about them.’

‘Need I remind you that everything is in short supply? If there is some material for coats, surely we want it to be given to the manufacturers of coats for our brave soldiers, who do not have a warm comfortable hostel to return to at the end of a working day. Greatcoats were ordered in plenty of time and will be delivered as soon as possible. To win this war we will all have to be disciplined, principled; we will have to make sacrifices for the greater good and, Miss Paterson, we will have to learn to obey the chain of command and not, do you understand me, not presume to think for ourselves.’

She turned and went to the window. Grace stood, wondering whether she had been dismissed or if she was to wait. She did not wait long.

‘Come here, girl.’ Grace joined her at the window. ‘Do you see that building over there?’

‘Yes, Miss Ryland.’

‘It’s a pigsty. Clean it. I expect it to be a shining example of good animal husbandry by teatime. Now get out.’

‘Yes, miss,’ said Grace, and walked out, closing the door very quietly behind her.

After supper that evening, Betty Goode loaned Grace the notes she had made at the lecture and then she play-acted the lecturer in the hope of cheering Olive, who was lying in bed.

‘He was a real hoot, Olive; everything you need to know about farming in one easy lesson. Picture him, not much bigger than me and hands like big hams – do you remember hams in butchers’ windows? He’s got about three hairs stretched across the shiniest head you ever saw and he’s wearing absolutely immaculate dungarees and shoes so shiny you could see your face in them. Don’t think he’s ever been on a farm, but anyway, this is him, fingers stuck in his braces, striding up and down the lecture hall.

‘ “Growing crops is simple, ladies. First, plough your field, modern tractor or the magnificent British horse. Next, harrow it. What comes next? Of course, sow the seed. We has machines as do this evenly nowadays or you can scatter – will depend on your farm. Next, weed as crops grow – the damned things will be the bane of your life. After that, you can leave it to Mother Nature. Water, if necessary. And then, the joy of watching golden wheat swaying in a late-summer breeze or superb English peas fattening on the climbing stocks. Lovely. And what do we do last? Yes, harvest and enjoy the fruit of your labour. Now, ladies, could anything be easier than that?” He did not wait for an answer. “No, thought not.” ’

Grace interrupted the performance. ‘Sorry, but didn’t he say, “It’s bloody awful”?’

‘No, he did not, Grace Paterson. Kindly don’t interrupt again.’

They were pleased to see a smile on Olive’s pale face.

‘I’ll continue, Olive,’ Betty said, and, taking a deep breath, she got herself back into character.

‘ “Now should you be asked to plough, here’s a little tip. Ladies has delicate ‘sit-down upons’. I always suggest a nice, if somewhat scratchy sack of straw, easier to find on many a farm than the farmer’s missus’s best cushion. Tractors is noisy, slow, and they have a bad habit of stalling, but, on the bright side, you won’t get so many horseflies buzzing around you. You will still get them, and wasps and bees buzzing away. Just think of the honey from the bees – can’t think why the Good Lord invented wasps, oh, yes, must be fertilising. See, everything in its place. Any questions?”

‘Of course, he didn’t give anyone a chance to ask him anything,’ said Betty, ‘but said, “Thought not. All right, where are you now? Some of you is pigs, some hens. Have a good afternoon.” ’

Grace laughed. ‘You remind me of a friend who’s a real actress, Betty: you’re good, isn’t she, Olive?’

Olive seemed too weak to reply. She had shivered through the talks on the care of pigs, and the egg producer’s place in the war effort – ‘a hen will lay an egg if it’s properly fed, watered and housed, but you can’t order it to lay. She’ll do it when everything is right and it’s the farmer’s job to see that conditions are perfect’ – gulped tea at the break between lectures and had then caused a small sensation by collapsing in the lavatory. Miss Ryland had been forced to admit that Miss Turner should be given two aspirins and a hot-water bottle and sent to bed.

Grace, on the other hand, had spent what was left of the afternoon and much of the evening cleaning the pigsty. All bedding and food waste had to be shovelled out, and the floor and walls washed down. George, the head dairyman, passing the pigsty in pitch-darkness and, alerted by the sounds of scrubbing, had slipped in quietly and seen a girl scrubbing the floor in the dark.

‘What the hell are you doing?’ he shouted.

Grace had no idea how to answer. She was exhausted, filthy, and knew she smelled as badly as the sty had smelled before she had begun to clean it.

‘I can see you’re scrubbing a mucky floor in total darkness. Whose bright idea was this?’

For a mad moment, Grace thought she might throw down her scrubbing brush and run, but she tried to remain calm. ‘Miss Ryland,’ she almost whispered.

‘Ryland? Good God.’ They stood in the covering blackness for a few moments in silence and then George obviously came to a decision. ‘Go and have a hot bath. You’ll miss tea if you don’t hurry and I’m sure she doesn’t want that.’

When Grace hesitated, he yelled, ‘Go!’ Then added more gently, ‘Now, lassie. Get cleaned up. I’ll explain to Miss Ryland.’

Grace, now in tears, had stumbled in the pale light of the moon to the hostel.

Later, as Grace left the dining room, Miss Ryland had stopped her. ‘You seem to have misunderstood me this afternoon, Paterson. You must learn to listen very carefully and to follow orders to the letter. Now we’ll say no more about the matter and, just this once, I’ll make no report.’

Grace could not bring herself to say, ‘Yes, miss,’ and after nodding abruptly she ran upstairs to join her friends.

She had still not written to her friends in Dartford but she sat beside Olive’s bed and thought about them. She compared them with Miss Ryland and castigated herself for being such a poor judge of character. ‘I actually thought she was a kind woman, a good and honest woman. Well, she doesn’t compare with the goodness and kindness of either Mrs Brewer or Mrs Petrie. I didn’t misunderstand her; I understood her only too well. She told a lie.’

‘Liberty bodices and woolly socks,’ she announced to the unusually quiet room. ‘I promised a liberty bodice to Olive.’ Then, turning to Olive, she added, ‘I think I have a pair of socks I can give you too, once we get you well.’

Other land girls stood up and began to go through their often-meagre belongings.

‘Every old lady in my home village knitted me warm stockings, Grace, and I bet there’s a knitted vest in here too,’ said a slightly older girl from Yorkshire. ‘Hate wool against my skin, I do, but what can you say to old ladies?’

‘Thank you very much,’ chorused several of the girls, and everyone laughed.

‘I can’t take all this,’ Olive wheezed, as knitted socks, stockings, vests and even knickers began to pile up on her bed.

‘Don’t fret; we’ll sort it out. We’re all in this war together, aren’t we, ladies?’ Betty made Olive smile as she pulled on a very large woolly vest over her pyjamas. Then she took it off and held it up. ‘Bit too small for me, this one. Any takers?’

Grace, still feeling both angry and unhappy, began to relax in the camaraderie. This was how she had joked with her old school friends. No one would ever take their places in her affections but she smiled as she understood that these young women too would always be a special part of her new life.

Two days later, Miss Ryland admitted that Olive was no better and telephoned for a doctor. Grace and Betty were allowed to stay with her while they waited.

Grace had no experience at all of medical care and could make no suggestions as to how to bring down Olive’s temperature. ‘She’s burning up, Betty. What can we do till the doctor gets here? Should we take off this heavy blanket?’ She made as if to move it.

‘No,’ said Betty sharply. ‘If I remember right, my nan used to put us in cold water when we had a high temperature and then quick as a wink, back into the nice warm bed, just till the temperature broke. I know she shouldn’t be in a draught.’

Grace looked around. ‘Wish there was a fireplace. I could easily find sticks and branches in the wood. It is a bit draughty.’ She walked angrily to the small window and tried to peer out. ‘Can’t see a damn thing. I’m going to run downstairs to watch for the car coming. I can’t just sit here.’

Olive coughed, a loud hacking cough that seemed to shake her whole body. ‘I’ll be all right, Grace,’ she wheezed.

That frightening wheezing had been heard too often in the past few days and, combined with the burning skin that made her attempt to throw off her covers, had added to the land girls’ worries.

Betty, who had lifted Olive up until the spasm passed, lowered her down onto the pillow. ‘You go, Grace, and bring back three cups of tea. You’d like a nice cuppa, wouldn’t you, Olive? See, Grace, she’s dying for some tea; me, an’ all. Run.’

Grace grabbed another jumper and pulled it over her clothes. There would be time to continue the fight for the promised coats when they had Olive well. She strained her ears to hear the ring of the doorbell but all she heard was the clatter of her heavy-soled shoes on the wooden staircase.

It was too cold to stand on the steps, looking down the driveway for the doctor’s car and so she decided to jog down to the gates in the hope of seeing it arrive. She reached the gates without seeing any vehicle of any kind, but as she stopped, leaning against the gatepost to get her breath back, she saw a bicycle at some distance. The bicycle slowly drew near as the rider fought both the wind and the weight of the ancient machine. Disappointment. A woman was riding the bicycle.

Grace had never felt so powerless. Olive needed a doctor, the doctor who should probably have seen her two days ago, but just then the wind blew the cloak worn by the cyclist and Grace saw a bright red lining.

‘A nurse,’ she shouted. ‘Nurse, nurse,’ she cried again as, her energy restored, she ran down the road to meet her.

The nurse had no breath left for talking but she handed Grace her medical bag and, her burden lightened somewhat, they reached the hostel together.

Miss Ryland was there to meet her. ‘We sent for the doctor. Where is he?’

‘You’ll have to make do with me; I’m the district nurse, Nurse Stevenson, and Doctor’s too busy. Now, if I could see the patient … Honey in hot water with maybe a splash of brandy is the best medicine for colds. I’m sure I didn’t need to cycle out all this way. The call came right in the middle of my first-aid class.’

She was making her way up the steps and into the hostel, Grace following along behind, carrying the rather heavy and well-used medical bag.

Miss Ryland decided to be charming. ‘We are sorry, Nurse, to tear you away from war work but we too are in the middle of the war effort and the health of our students is, naturally, our first priority. The girl is rather delicate and possibly should not have been accepted into the Land Army, especially in the middle of winter.’

She continued upstairs at the district nurse’s side and Grace followed on behind.

Very few of the girls had an appetite for supper that evening. There was a roaring fire in the large room used as a dining room, and a delicious smell of roasting potatoes almost hid the mouth-watering odour of roasting apples, but the room, although filled with healthy and hungry young women, was unusually quiet.

The district nurse had taken one look at the shaking, sweating Olive and, with an angry, ‘She should have been seen earlier,’ sent her to the nearest hospital.

‘Pleurisy?’ the girls questioned one another. ‘What’s pleurisy?’

‘Ask Grace Paterson. She were with her. What is it, Grace, something like pneumonia, maybe?’

Grace, who was chopping a roasted potato into tiny pieces but making no attempt to eat it, shook her head. ‘Nurse didn’t say. I think it’s lungs but I’ve never heard of it. Really sore chest and difficulty breathing; Miss Ryland’s gone with her.’

That news had a mixed reception. Most were pleased that the hostel manager had accompanied Olive to the hospital, but some were afraid that her doing so only proved how ill the land girl was.

Voices were raised in anger. ‘She’s one of the girls without a coat. We was promised proper clothing.’

‘Only the latest intake’s short, girls,’ someone tried soothing frayed tempers. ‘And the coats is promised.’

‘Come on, ladies, look at the lovely supper,’ another said. ‘Eat up, that’s real custard with them apples. Tomorrow’s another day and we don’t want no more getting sick now, do we?’

The muttering and grumbling died down as healthy appetites were appeased. Some looked round at the warm, comfortable room, with its fire, its benches and old sofas piled with cushions, the shining brassware on the walls, and reflected that, yes, the work was hard but the billet was a good one. A girl, possibly one who should not have been accepted for such arduous work, was sick, but she was receiving the best possible care. Tomorrow, they would learn even more and, one day, equipped with hard-won knowledge and experience, their lives would be even better.

Grace’s dormitory was not so quiet that evening. Well aware of how early they had to be at work next morning, the land girls remained unable to settle down and sat up in their beds going over and over the events of the past few days. Only Grace and Betty Goode, the two most closely involved, were quiet. What was the point of talking and losing sleep? Olive was now receiving the best of care – no one, thought Grace, could have done more than Nurse Stevenson – but hospital staff surely had equipment not available to a district nurse.

The loud ringing of the alarm clock had them stumbling in complete silence to wash and dress as quickly as possible. The working day began after breakfast and Grace was delighted to find that a lecture on crop rotation had taken the place of an on-site class on ditch clearing.

‘Great,’ said Betty. ‘Sitting in a nice, warm classroom has to be better than standing in freezing cold water, digging out who knows what. I found a sheep’s head in a ditch once.’

Grace agreed with Betty but, after only a few minutes, she found that her attention wandered to the hospital bed where Olive lay. Was there anything she should or could have done earlier? If she had noticed Olive shivering, if she had insisted that the girl wear more underwear, if they had been given their promised heavy coats – would she now be lying in a hospital bed?

She pulled her wandering mind back to the lecture: wheat followed by potatoes … or did potatoes follow wheat … or did it matter?

‘You didn’t make many notes, Grace,’ one of the roommates pointed out as they left the lecture.

‘None that make any sense,’ said Grace, looking at her lined notebook.

They linked arms and began to walk along to the dining room, where a fire was smouldering in the grate and mugs of hot Oxo or surprisingly strong tea were waiting on the long wooden table. Grace and Betty helped themselves to tea and moved away from the fireplace just as the door opened and Miss Ryland appeared. The room went silent.

Miss Ryland stayed near the door and looked around the crowded room. ‘Would the women in room eleven please come to my office?’ She moved as if to walk out, stopped, turned and with an unsuccessful attempt at a smile, said, ‘Do bring your hot drinks.’

Grace and Betty, in the act of lifting their mugs, immediately replaced them and walked to the door, followed by their roommates. No one spoke as they headed for the manager’s office.

It was not a large room: a smallish fireplace – where a meagre fire failed to defeat the chill – an enormous desk, two armchairs, a metal cupboard with a key in the door, and two folding chairs leaning against the wall. There was scarcely enough room for the land girls.

Miss Ryland surveyed them, avoiding direct eye contact, and, at last, straightened up. ‘There is no easy way to say this, ladies, but the infirmary rang and … Olive Turner died early this morning.’

Grace stood transfixed. Dead? How could Olive be dead? She had had cold feet. Her pre-war liberty bodice had been left at home as she had left off her childhood. She heard a voice ask loudly, ‘Why?’ and realised it was her own. The voice – her voice – went on: ‘Why did she die? She caught a cold, a simple cold. Why did it suddenly become this pleurisy?’

The other land girls began to murmur and the murmurs rustled through the room like leaves falling from a tree. Miss Ryland appeared to take a deep, calming breath.

‘We women of Britain are all in the army, soldiers fighting in our own way. In another time, it’s likely that Miss Turner would not have been accepted into the Land Army. Yes, she had a cold, but it developed very quickly into pleurisy … with added complications.’

The girls released a collective gasp, looking at one another in horrified disbelief.

Miss Ryland continued, speaking even more quickly, ‘The hospital staff did everything they could, everything, but—’

Grace interrupted, ‘We didn’t. You didn’t. You as good as killed her.’ Grace could hear her own voice, strident, shaking with emotion. She wanted to stop but the voice – her voice – went on. ‘You didn’t listen. Why? Because—’

She got no further.

Betty Goode was there, holding Grace in her arms, explaining, making excuses.

‘Enough. You are dismissed, except you, Paterson.’

Grace, feeling as if every ounce of strength had left her body, watched the others leave; some sent her sympathetic looks, others looked away as if perhaps afraid of being associated with her and her uncontrolled outburst.

For a time, Miss Ryland said nothing. Grace looked straight ahead. She remembered standing in terror in front of Megan and, before that, surely a long time ago, she had stood in an office like this one – but who had stood talking to her? No matter; pieces of memories came and went and they would perhaps come again and become clearer. She waited as the manager moved to the window, stood there looking out, returned, fiddled with some pencils on her desk. Several needed to be sharpened.

‘I would throw you off the course if I could, Paterson, but somehow you have made a better impression on Mr Urquhart, and he is likely to vote in your favour. Unfortunately, galling as it is, he has more clout.’ She moved closer to Grace and stared into her face. ‘Listen to me. You go to your room, stay there until teatime, say nothing to the other girls and, for the remainder of the course, keep out of my way, and maybe, just maybe, you’ll pass. Now get out.’

Grace walked out, her legs trembling. Had she ever before seen such hatred in anyone’s eyes? Megan had looked at her in annoyance but surely never with hatred. She stood for a moment at the foot of the staircase, holding on to the banister, and a small nervous giggle eventually escaped. Who on earth was her champion, Mr Urquhart?

Room 11 was empty. Grace walked over and sat down on her bed. Dead. One moment alive and the next dead. Poor, poor little Olive. Grace could not let Daisy Petrie go out of her life so easily. She got up, took out her notebook and quickly, without conscious thought, scribbled a note to Daisy:

Dear Daisy,

I’m all right. Tell everyone I’m sorry and please forgive me. Hope everyone is well.

G.

She had been thinking of a special Petrie as she wrote.

I’ll tell them everything soon, Grace decided.

Having written at last, she felt a great weight had been lifted from her, and she stretched and looked around the room.

Next to her bed was Olive’s, with its large pile of extra clothing donated by the others. Poor Olive did not need them now.

‘Senseless not to take them back,’ most of the others said when they returned to the room after tea. ‘Who knows what kind of digs we’ll get next month? Might well be grateful for an extra vest.’

Grace left her spare vest and thick stockings on Olive’s bed, and sighed with relief when, somehow, a few days before graduation, they disappeared.

By the time the last day of the course came round, daffodils had sprung up all over the farm and a lilac tree near the front gate promised to burst into perfumed full bloom.

‘Sorry I won’t see that,’ said Betty.

Grace and Betty were walking together towards the bus that was to take them to the nearest railway station, where they were to begin their first journeys as fully accredited land girls.

Golly, Betty, I’ve done it – we’ve done it. Stupid, but sometimes I believed it was all too good to be true. We’re land girls, qualified, and I can almost believe I smell lilac.

‘Happen there’ll be plenty of lilac everywhere in the next few weeks,’ a male voice interrupted them. It was George, the dairyman. ‘I’m taking a heifer over to Bluebell Farm, ladies. Station’s on my way, if you don’t mind squeezing in.’

‘Fantastic,’ the girls chorused.

‘Even prepared to squeeze in beside the heifer,’ Betty said, laughing, but she was quick to scramble up in the front of the dependable old Austin K3, beside Grace.

They drove in silence for a time and it was only when they were on the main road towards the town that George spoke: ‘Nasty business over that lassie.’

Their euphoria evaporated and the girls nodded quietly.

‘Learn us all to err on the side of doing too much too early rather than too little too late.’ He leaned forward and wiped an imaginary speck off the inside of the window. ‘Happy with your assignments? Together, are you?’

‘Unfortunately, not,’ Grace spoke first. ‘Betty did really well and is off to a lovely farm in Devon. Me? I didn’t cover myself in glory and so I’m off to some farm no one’s ever heard of.’ She did not add that her relief at the knowledge that she need never look at Miss Ryland again or hear her voice threatened to make her sick with excitement. She wanted to sing, to jump up and down with happiness, but it was impossible to do either at this precise moment.

George’s emitting a sound that could possibly have been an attempt at laughter broke into her thoughts. ‘Happen you’ve landed on your feet; you have friends, you know.’

‘We all thought that, too, George,’ said Betty, ‘although she’s hard to convince. There’s a Mr Urquhart who’s been in her corner more than once.’

‘Aye. Thrawn bugger, Urquhart. Just be careful to pick your fights carefully, Paterson, and you, too,’ he added, looking at Betty. ‘Now here’s station; out you get.’

The two land girls dropped down to the ground and hurried to the back of the lorry to retrieve their suitcases. ‘Thanks, George,’ they said together.

‘If you should see Mr Urquhart—’ began Grace.

‘Expect he knows already, lassie. Cheerio.’

He drove off, leaving the two girls standing looking after him.

‘He couldn’t be.’ Grace continued to look until the dilapidated-looking lorry was out of sight.

Betty started to laugh. ‘He could, you know. I bet you half a crown that he’s your knight in shining armour.’

Grace shook her head. George was a kind and patient, if demanding, teacher, but a knight in shining armour …? There was no opportunity to dwell on it, though, as there was little time to spare before they caught their different trains.

‘You will write, Grace?’

Grace promised, although even as she did, she remembered all the letters that needed to be written. I will be better organised. I will keep in touch with Betty but, before I do, I will contact all my old friends.

Only when she was seated in the railway carriage, which was for once not crowded, did she have time to think about her new posting. Miss Ryland had given her an unsatisfactory report and dismissal had been threatened. Mr Urquhart had intervened and, instead, Grace was being sent to a large estate that had only just requested government aid.

‘Urquhart thinks you’ll do us proud, Paterson,’ Miss Ryland had said when she had told Grace of her new posting. ‘It’s a rather grand estate, owned by a real lord, not that anyone like you is ever likely to be anywhere near him or his family. You’re to be given quarters in the main house, somewhere off the scullery, I expect, so you’ll feel right at home.’

Grace would not allow herself to be baited. She felt strongly that Miss Ryland was hoping that she would say something that would lead to dismissal but she would not give her the satisfaction.

How could she have taken me in so easily? Grace asked herself again. I thought she was a good, caring person.

Miss Ryland turned away abruptly, as if she preferred not to show her face, stood for a few moments, and then turned again, once more in control. ‘You do understand the phrase “grand estate”? Not only is it the seat of a nobleman but also it is extensive. Unfortunately for you, his lordship encouraged the estate workers to enlist and he is now … rather short of manpower. Possibly several qualified land girls will be assigned there in due course, but meantime, you, a few of his retired workers and whoever else can be found will be working the home farm – and possibly his other farms. Do you have the slightest idea what that means? A few elderly men and Grace Paterson, land girl, will be responsible for the year-round work of a large farm; not only your favourite tasks – milking docile cows and delivering that milk – but cleaning shit-filled byres, and real farming: preparing the soil, ploughing, sowing, feeding, weeding, harvesting. I’m sure you grew up in some mouse-ridden slum but have you dealt with rats, Paterson? And I’ve scarcely begun. Oh dear, you will be tired. Certainly, there will be no time for sticking your nose in where it’s not wanted. Dismissed.’

Now Grace looked out of the window and heaved a sigh of relief. Despite everything, she had made it. She was a land girl and she was being sent to work on a farm. She could handle anything, including rats, she decided with a tiny shiver. Life could not possibly get better. The bubbles rose again and cavorted about in her stomach. This is the beginning of a fantastic new life, Grace, she told herself. Look forward to the future and try to remember only the good things about the past.

TWO (#uc6202466-c7f9-5b40-b7a6-590c3cd4dc7f)

Bedfordshire, March 1940

She had never been so cold in her life. Grace stood in her pyjamas beside her abandoned bed and wanted nothing more than to climb back in. Where were her clothes? It was so dark that she could see nothing.

Don’t panic, Grace, she told herself. You’re standing beside the bed, and the chair where you put your clothes is … She bent down and felt along the bed until she came to the short iron foot rail. She turned round so as to be facing the head. ‘Yippee,’ she whispered through chattering teeth. She stuck out her right arm and followed its path till she stumbled against the easy chair that she had nicknamed Saggy Bottom the night before. Her clothes were folded up in a neat pile on the collapsed chair seat. She felt through them until she found her knickers and, as quickly as she could, pulled them on. Next, her thick – and blessedly warm – woollen socks. A cream WLA-issue Aertex shirt and a warm green jumper followed, and, last of all, her corduroy breeches. ‘I hate you, silly breeches,’ she said as she struggled with the laces at the knees. She had not yet mastered how to get the breeches on or off quickly. Under the door, she saw light shining in the corridor.

‘Are you awake, Grace?’ called a voice.

‘Yes.’

The door opened and she saw a female figure. ‘Welcome to Whitefields Court. If you didn’t catch the name of the station, it’s Biggleswade and we’re in Bedfordshire.’ She changed the subject very quickly: ‘Why are you dressing in the dark?’

The woman did not wait for an answer but struck a match, which flared up for a moment, showing Grace someone probably the same age as her sister, but who was dressed exactly as Grace would be dressed if she could see to wash and finish dressing.

‘Why haven’t you got an oil lamp?’ The woman sounded brusque but kind.

‘It wasn’t issued.’

A second match flared and the woman walked across to the little dressing table and lit the candle that sat there. ‘There, now you can see your way to the lavatory. Don’t be shy, girl. We all go. If you’re downstairs in five minutes, you can have a cup of tea to warm you before the milking. Otherwise, you’ll have to wait till it’s finished. Now scoot.’

Grace ‘scooted’. Something about the voice suggested that the woman was used to being obeyed without question, and besides, Grace wanted a cup of tea, hot and sweet – well, that would be nice, but hot would do.

She had never washed and dressed so quickly in her life but, carrying her heavy WLA-issue boots, she fell into the kitchen no more than five minutes later. Mrs Love, the woman Grace had met the previous night – possibly the cook or housekeeper – was busy at the large, shiny kitchen range, and the woman who had been in Grace’s room was leaning against the sideboard, smoking a cigarette. She looked Grace up and down. ‘Give her some tea in a tin mug, Jessie, and she can drink it as we go.’

‘Yes’m.’

Grace had never really believed that people actually said, ‘Yes’m,’ but that certainly seemed to be what Mrs Love had said.

‘Don’t gawp, Grace, frightfully rude. Now, bring your tea. She’ll be back in time for breakfast, Mrs Love.’

Was there a warning note in her voice? Grace wondered, but she took the mug, thanked Mrs Love and followed the other woman out into the darkness. Biting cold hit her like a shovel.

‘Where’s your greatcoat?’

As Grace stumbled over her answer, the woman interrupted her. ‘Don’t tell me: wasn’t issued. How does this country expect to win a war?’

Grace assumed, rightly, that her companion did not seek an answer to that important question; at least, not from her. She tried to gulp the hot liquid as she hurried, in the pitch-darkness, after her. Must be the boss one from the War Office, she thought. Never thought they’d be awake earlier than the workers, or even here at all. Maybe it’s because it’s my first day.

A large rectangular shape loomed up before them and a faint glow showed Grace that it was a building. Cows, she realised, lovely, lovely warm cows. Milking was never going to be her favourite job – whatever Ryland had said – but sitting with her head close to a cow’s bulky side was warmer than being outside.

The woman from the ministry was as keen on cleanliness as George had been at the training farm. ‘We have managed to avoid tuberculosis, foot and mouth, and God knows what other diseases these lovely silly animals get, Grace, and absolute hygiene is the key. There will be a clean overall on the door for you every morning and I will inspect your hands – sorry – until I know that I can trust you.’

‘The dairyman at the training farm was a martinet.’

The woman laughed. ‘Ah, old George, best man in the business. You can see that we don’t yet have the new-fangled milking machine. Neither do we pasteurise, on this farm, partly because our local customers tend to want milk “straight from the cow”. They like what they call “loose milk”, not bottled, and we do the old-fashioned churns and jugs. As with you and your greatcoat, however, I’m assured that modern methods are on the way. Now let’s get started.’

Grace looked: there had to be thirty or forty cows waiting patiently to be milked. The byre was full of the sweet smell of hay overlaid by another smell, familiar and not entirely unpleasant but certainly more pungent. She had smelled it often, if not quite so strongly, during her training. ‘Ugh,’ she said, and buried her nose in the warm side of the cow she was milking.

‘All part of the fun of the farm,’ said her companion. ‘I’ll start at the other end, but shout if you need help, and watch big Molly, third down; she loves to knock over the pail.’

Great, thought Grace. Is there going to be a cow on every farm whose joy in life is to kick the milk or me? First day: no breakfast yet, and a cow that plays football. But Molly gave her no trouble as she worked her way steadily along her line. Eventually, she was side by side with the War Office lady and was troubled to see that she had milked at least five more cows than Grace herself had. Grace watched her surreptitiously, as they worked side by side. What beautiful hands she had. Her nails looked professionally manicured, just like her sister, Megan’s, but better. She looked at her own work-worn hands and sighed.

‘Problem, Grace?’

‘No, miss. I have a school friend who’s with ENSA and your fingernails reminded me of her.’

‘These won’t last long with milking. I should have cut them but hadn’t time. And please don’t call me “miss”. I’m his lordship’s daughter. Doing my bit, too. Call me Lady Alice. Now, can you find your way to the kitchen? Off you go. I can spare you for thirty minutes. Back here for deliveries as soon as.’

Grace hurried and her mind was working as quickly as her feet. She had been working beside an earl’s daughter. When she did write, she would tell Daisy that. And she was just normal, she would say, slim and elegant, with really pretty brownish hair and the creamiest skin, and knew better than me how to milk. Imagine. War did strange things, did it not? Lady Alice had been wearing a land- girl’s uniform, just like Grace’s own, with the exception of that lovely warm coat. ‘Doing my bit, too,’ she had said.

Two men were eating breakfast at the long wooden table in the kitchen and Grace hesitated for a moment.

‘If you’re here for breakfast, Grace, sit down,’ said the cook. ‘I’m not handing it to you over there. They’re only men, you know. They don’t bite.’

One of the men laughed and Grace saw that he was quite young. ‘Do join us,’ he said. He gestured with his hand, as if to point out the size of the table. ‘Sit down as far away from us as you like. We’re the unpatriotic conchies.’ There was a note of sarcasm in his voice. ‘We’re what’s called noncombatants, but we’re important, too, and we don’t bite.’

Grace blushed and sat down but chose a chair not far from the older man’s place. Conchies? Conscientious objectors. She had heard of these men, whose principles would not allow them to fight in the war. Surely, that did not make them unpatriotic.

‘Hush, you, Jack. You’re after scarin’ the lass,’ the other man said. ‘She only arrived last night and probably thought she was going to be alone. We’re clearing the ditches, and happen you’ll only see us at meals.’

Grace smiled at them tentatively. She was used to working-class men like the older man, but the tall, and somewhat aloof Jack, with his plummy voice, was rather different.

A plate was put before her and she forgot about the men as she looked at it. Bacon, two eggs, some fried potato and a thick slice of bread that had obviously been fried in the bacon fat. She wouldn’t mind how much work she had to do if she was to be fed like this. ‘Thank you,’ she said, with some awe in her voice.

She could not help comparing this table with those in the training school. No named individual pots here, but two large bowls, one full of butter and the other of marmalade.

‘There’s tea in the pot,’ the red-faced cook said as she returned to her range. ‘Pour yourself some.’

Grace looked askance at the round brown teapot and wondered if she could lift it up and pour without spilling.

The older man spoke again: ‘That slip of a girl’ll never lift such a heavy pot. You’re nearer to it, Jack, lad.’

Without a word, Jack poured Grace’s tea. She was embarrassed to be the focus of so much attention, but she thanked the men for their kindness and began to eat.

For some time, no one spoke, and Grace wondered if it would be thought forward of her to start a conversation. At the training farm, everyone had talked all the time. Why should this farm be any different?

‘Clearing ditches must be hard work.’

The men looked at her and then, without a word, reapplied themselves to their almost-empty plates.

The atmosphere in the room, never light, was now really heavy.

‘Not hard enough for shirkers,’ the cook said in an acidic tone.

The men stilled for a moment and then continued eating.

Grace took her courage in both hands. ‘It’s one of the most vital war jobs,’ she said quietly. ‘At the training farm, the lecturers told us that before 1939 more than half of Britain’s food was imported. Now, our farmers are being told to double or treble their production, and if the ditches aren’t cleared then the fields won’t drain and crops will rot.’

Embarrassed, she gulped some tea and stood up to go. The cook stood, arms folded, and the look on her face told Grace that, once again, she had made a bad enemy.

‘I’m Harry McManus,’ said the wiry older man, standing up, ‘and thank you, little champion. Young Jack Williams here was learning to be a doctor and save lives, even ones like ’ers,’ he added with a nod towards the robust figure of the cook. ‘I were a bus conductor before. Must say, I like being on a farm. How did you get into it?’

‘You’re all here to work, not chat over the teacups,’ the cook said, reinforcing her position.

Grace smiled at Harry. ‘I volunteered,’ she answered. ‘I’m off to deliver milk,’ she told the men as they moved together towards the door.

‘If her ladyship hasn’t froze to death waiting for you.’

Grace gasped and hurried out of the kitchen. Had she taken more than thirty minutes? ‘Please, please …’ she muttered as, hampered by her heavy boots, she tried to run.

Lady Alice was seated in the delivery lorry, and all she said as Grace climbed in was, ‘There’s an old coat of mine just behind you, Grace. It’ll do for now, but I will ring up about your uniform one. As usual, they’ll assure me that it will turn up one of these days.’

She had started the engine as she talked and they headed out of the farm.

‘Thank you. I don’t mind waiting, Lady Alice.’

‘I mind. Wear the coat.’

They drove in silence, Grace going over and over in her head all the things she thought she should have been saying. Seeing Lady Alice in the uniform, albeit a uniform that had been made to measure from finer materials, had made Grace think of all the unwritten words describing her WLA uniform she had intended to write to her friend Daisy. She had intended to say it was smart and attractive. In fact, it was ugly, utilitarian and quite inadequate for winter conditions. Her shoes were extremely heavy: wearing them all day exhausted her and she often had blisters on her heels and her toes. But at least no one else had ever worn these clothes; they were hers.

‘Cat got your tongue?’ asked Lady Alice eventually. ‘Relax, girl. Now, when we get to the village – which is called Whitefields Village, by the way – you take the measuring can, which is beside the churns in the back, fill it with milk, and then go to the first house. Knock, and if no one answers, walk in, the door will be open, and the housewife’s measuring jug will be on the sideboard or the table. Fill it, come out and go to the next house. There will probably be one or two people up, having breakfast, getting ready for school or work. Just say, ‘Hello, I’m Grace,’ and you’ll be fine. Any questions?’

‘No, Lady Alice. Thank you for the coat.’

‘“The labourer is worthy of his hire.” Right, I’m stopping here. Coat first and then the milk.’

Grace stretched in the general direction of her employer’s pointing finger until her hand met something soft. She grasped the material and pulled.

‘You’ll need two hands, Grace; it’s bigger than you are.’

Grace pulled with both hands and, eventually, the coat gave up the fight and fell over into the front seat. Grace looked at it in awe. ‘Lady Alice …’ she began.

‘It’s twelve years old, Grace. I trust it will keep you warm until the Requisitions Department has its house in order. Now, for heaven’s sake, girl, put it on and deliver the milk.’

The dark brown skin coat was fur-lined and very heavy. The weight surprised Grace as she struggled into it. It was so long that it reached nearly to her ankles and, initially, made walking rather difficult. Grace felt sure that, even if she were to lie down in the street wrapped in this wonderful coat, she would still be cosy and warm. The thought made her smile. ‘But I’m not going to experiment,’ she said aloud as she reached the first house. She knocked, opened the door and found herself in a small, dark room, where the smell told her that the fire had been banked up with potato peelings in a futile attempt to keep it burning until morning. She made out the shape of a jug on the wooden table top, filled it, and hurried out as quickly as possible. She had been brought up in poverty and the sight of it was just as depressing as it had ever been.

A gas mantle lit the next small house. A tired-looking woman was bending over the fire where a pot bubbled.

‘Oh, thank you, miss,’ said the woman with a smile. ‘You’re new. Where did the other girl go? Woman really, much older than you. I’d enlist myself if I didn’t have three upstairs waiting on their porridge.’ She stopped stirring and stood up. ‘And another one on the way. There’s the jugs. I take two lots on a Friday; get my sister’s lads for their dinner.’

Grace filled the jugs, smiled at the woman, said, ‘See you tomorrow,’ and hurried back to the milk lorry.

‘I should have warned you about Peggy; she’ll talk your head off given half a chance. Nice woman and a good mother but we don’t have time to chat. I suppose children are more difficult than animals because they certainly let one know when they’re hungry. Not being a mother, I can say that animals are just as important. Does that shock you, Grace?’

There was no time for Grace to answer even if an acceptable answer had occurred to her. Megan had certainly thought anything and everything more important than the one child she was supposed to look after, but not everyone was as selfish as Megan.

Lady Alice knew the area well and effortlessly manoeuvred the lorry and its rapidly diminishing load up and down dark, narrow streets and alleys, until the last customer in the grey-stone village had been served.

‘Can you drive, Grace?’

The question surprised Grace, who, eyes closed, was drifting into a doze.

‘No, Lady Alice. I can ride a bicycle and I’m not afraid to dangle on the broad back of a shire, but that’s as far as it goes.’

Lady Alice made a very unladylike noise. ‘Should we ever need to deliver milk on horseback, I’ll remember your talents, but we really need someone who can drive. Otherwise, I will spend the rest of the war driving a milk float.’

Grace thought of her friends, Daisy and Rose Petrie. Both of them could not only drive but also maintain car engines. Their father and their brothers had taught them. ‘Do none of the men drive, Lady Alice?’

‘Just how many men have you seen on the estate, girl? Most of our young unmarried men enlisted after a rousing talk in the village hall. Saw themselves coming home heroes, I think, God help them. The married men stayed. We have a few middle-aged farm hands with a wealth of knowledge and experience between them, and several retired men who’ve come back. They live either on the estate or in the village and most work a full day. “Farm work keeps you fit”, could well be a slogan. Not one has even driven a tractor.’

‘The two men—’ began Grace.

‘Are you deaf? There are no …’ Lady Alice paused, thought, and began again: ‘Sorry, Grace, you mean the conscientious objectors. I’d forgotten about them. Like you, they have just arrived. Yes, they’re men, and I suppose you’re right and there’s a good chance that the student one can drive. They are, however, supposed to cut down trees and dig ditches – very sensible use of a medical student, don’t you think?’

Grace hoped she was not expected to answer that question, although there was something in Lady Alice’s voice that made Grace wonder what her employer was thinking. She herself thought that a medical student would be more sensibly employed studying medicine, but who was she to say?

The pale grey light of early morning was beginning to spread itself across the sky. Grace sat up, anxious to get a proper look at the house where she was now living. The night before, she had been aware only of a huge mass at the end of a driveway that had to be longer than Dartford High Street.

‘Golly,’ she said as the great building revealed itself. Now she saw that the splendid sandstone building consisted of a magnificently proportioned central wing, standing proudly, and almost defiantly, between two other wings, which stood back from it a little, as if assuring the central building of its importance. The exquisite whole, its many windows looking out over possibly hundreds of acres of gardens and rolling farmland, was in the style Grace was later told was Jacobean. As it was, she could only gasp and admire. ‘That’s one house, for one family. It’s bigger than all the houses on our street stuck together.’

Lady Alice glanced across at her. ‘Quite something, isn’t it? One never really thinks about the house one lives in. Whitefields Court began as a monastery in the sixteenth century. My family was given it, and most of the land, villages et cetera around it, for reasons best left quiet, just before Henry the Eighth died.’ She stopped in the driveway, as if to see the house better. ‘Most of the land has been sold off, of course. Frankly, I’m never quite sure whether that was a good or a bad thing – being given the house, I mean, not selling the land or poor old Henry dying.’

‘But it’s beautiful.’

Lady Alice started the engine again and swept past the shining windows on the front, carrying on around the building to the kitchen entrance, where she parked. ‘Beauty doesn’t keep out rain. Right, out you get. Lunch is at one, in the kitchen, but now I want you to go to the tiled barn near the dairy. Bob Hazel, one of our senior men, is waiting there to show you the home farm and give you an idea of what will be expected of you. I’ll see you in the dairy tomorrow morning.’

She raised a hand, either in dismissal or farewell, and walked off towards the rear entrance. Grace, conscious of the waiting Bob Hazel, hurried to the barn.

At first, she was sure the building was empty. It was very quiet, peaceful really, and there was a pleasant smell of hay, although, from where she stood at the entrance, Grace could see no evidence of bales. ‘Hello?’ she called. ‘Mr Hazel?’

‘So, you’re our land girl? Well, I’m not likely to make rude remarks about your size, knowing full well that small packages often hold the best presents.’

Grace stifled a laugh, for the old man who had appeared from behind a large container was scarcely an inch taller than she was and just as slender. The hand that gripped hers, however, was hard and strong. She looked into his face and saw strength there and tolerance.

Too fast, Grace. You judge too quickly and you’re usually wrong.

‘Good morning, Mr Hazel.’

‘Hazel’s fine, since I hear tell I even look like a nut.’ He looked her up and down. ‘Had much experience?’

‘Four-week course, sir … Hazel, and I once had a try at growing vegetables in the back garden.’

He was silent for a moment and Grace looked down at her booted feet.

‘Come on then. I’ll show you round. You’ll get plenty learning here. How did your garden grow?’ he asked with a little smile.

‘Frost got some.’

‘Happens.’

Hazel was a man of few words.

The next few hours left Grace both exhausted and stimulated. The home farm covered almost two thousand acres but the seemingly untiring Hazel assured Grace that she had not, as she thought, walked every acre of it. She had seen vast neat acres of young crops, several fields that still had to be cleared and ploughed, grazing cows, hedgerows already in bud, trees that had to be hundreds of years old, ditches in various conditions, a fenced area where several pigs lay happily snoozing in the dust, a few cottages, each with its own well-cared-for garden, and a multitude of farm buildings, both ancient and modern.

‘Somehow, we have to get most of the land into production, Grace. We’ve sold off or slaughtered most of our animals, but the cows are very important, and the pigs. I’ve got some hens in the garden and, if I have more eggs than me and the missus need, then I bring ’em up here. We grow wheat, potatoes, barley, beets …’ He stopped talking, and Grace was saddened by the look on his face.

‘When I started here, more than forty years ago now, this place was a paradise. We grew everything, even had peaches and melons. Ever had a peach, Grace?’

‘Tinned, yes.’

‘Then, believe me, you never tasted a peach. Off the tree, warm in your hand from the sun through the glass, you bites into it and the juice, sweetest juice you ever tasted, runs down your chin. Now we has to do basics and I hasn’t got the manpower. If ’is lordship were ’ere, maybe we’d get more done faster, but Lady Alice works as ’ard as me, for all she’s a lady. She has got us a tractor. She drives it, bless her, and is teaching me, and that will speed up ploughing. There’s a new one ordered for you – a Massey-Harris. Know anything about them?’

‘I can’t drive.’

Hazel’s thin face wrinkled with laughter. ‘God love you, you don’t drive this model, you guide it.’

Grace tried to smile. At least the sun was now shining and areas of the estate were absolutely beautiful; they had walked the length of a brook and seen masses of tiny yellow primroses and even clumps of pink ones. Grace had bent down in wonder to see these exquisite little flowers and wondered if she would be permitted to pick some for her room. She felt that somewhere, a long time ago, she had seen such carpets of spring flowers.

Couldn’t have been Dartford, she told herself, although there were primroses on that farm I trespassed on with Daisy. She tried to bring back the memory that, annoyingly, hovered just out of reach, but Hazel’s voice interrupted her. He was pointing to a small cottage.

‘That’s mine; me and the missus lives there. No electric yet, but we’ll join the grid same time as the oldest part of the Court. Can’t wait. We have in the back some rabbits, an’ all, and I grows flowers in the front: roses mostly, but I love chrysanthemums; have a great show in the autumn.’

‘I look forward to seeing them,’ said Grace.

A look of doubt crossed the old man’s face. ‘I doubt you’ll last, Grace. Too much work …’ He stopped, as she was obviously about to argue with him. ‘I can see you’re a worker and, happen, we’ll be able to get a bit done but, with the best will in the world, unless they send more land girls, or prisoners even, there’s just too much work. His lordship expects to take in refugee families – plenty of rooms, but a lot of them are empty – and he hopes as some will be of help on the farms.’

‘A place this size must need dozens of workers. Lady Alice said all the young men enlisted.’

‘His lordship was called to the War Office and so we hardly see him now. He pops down of a weekend to give her ladyship a bit of company of her own sort but he’s committed to the war effort. Probably shouldn’t tell you, but the young man as Lady Alice walked out with enlisted as soon as war was declared and most able-bodied men around here did, too. Better chance of getting the service they wanted.’

‘But farming’s a reserved occupation.’

‘And very dull if you’re just doing it because it’s a job. You has to be bred to it, I think. The young ones liked the uniforms, the chance to see the world. I were like that myself in the Great War and what I saw of the world was blood-soaked trenches. Best day of my life was then day the war ended and I could get back here.’

‘And you’ve lived here all your life?’

‘Apart from the war. Born here, like my father, my grandfather and as many greats back as we can name – happen as long as the earl’s family. Backbone of England, we are. What more does a man need than a good wife, a good job and a decent employer?’

How wonderful to be so contented, Grace thought, as she listened to him.

‘Where are the farm workers now, Hazel?’

‘You’ll meet them all when we has our dinner. I make up a work roster with Lady Alice every Friday evening and that tells us where we’re supposed to be. Mrs Love can read and she has a copy in the kitchen.’ He looked at Grace questioningly for a moment. ‘You getting along all right with Jessie? She’s a good woman, a widow woman, and ’er son went off to join the navy.’

To Grace, he sounded as if there might be some doubt about Grace’s relationship with the cook. Grace did not want him to be concerned. ‘Of course, Hazel, fantastic breakfast she made.’

He seemed happy with that answer. ‘Good. She can be a tad snippy at times, worries about her boy, you see. Don’t remember when she last heard from him.’

Grace nodded. She could understand that. But his remark reminded her that before another day dawned, she must sit down and write to her friends in Dartford. Why didn’t she write letters? What held her back? Her friends would love to hear all about Lady Alice and Hazel, and even lovely old Harry and … Jack. Grace found herself fascinated by Jack, his beliefs, his obvious education and culture, his voice, more like that of Lady Alice than of old Harry. The Petries, her friends? How often had the four of them vowed that they would be friends through thick and thin? And yet, she found reason after reason to avoid sitting down and writing letters.