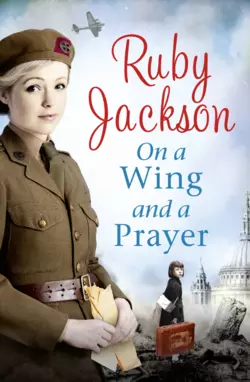

On a Wing and a Prayer

Ruby Jackson

The fourth in a series of books featuring four young women whose lives will be forever changed by WWII. Perfect for fans of Katie Flynn.Rose Petrie is desperate to do something for the war effort. Despite the daily hardships and the nightly bombing raids, her sister, Daisy, and their friends all seem to be thriving in their war work. Rose is doing her best down at the munitions factory, but she is dealt a blow when her childhood sweetheart, Stan, tells her he doesn’t feel the same way about her.Determined to get away and make a new start, Rosie decides to put her mechanical skills, learned from her father and brothers, to good use and signs up for the Women’s Auxiliary Service, or ATS. But Rose discovers that delivering fruit and veg in her father’s greengrocer’s van is very different to driving trucks for the army in a country under seize.While learning the ropes, Rose will learn that things never go according to plan, either in love or war. But with grit, determination and a bit of luck, Rose is determined that she, and the rest of the country, will keep shining through…

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Harper 2015

Copyright © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover photographs © Johnny Ring (woman’s face); Colin Thomas (woman’s body); Popperfoto/Contributor/Getty Images (refugee girl); Shutterstock.com (letter, plane, suitcase, background)

Ruby Jackson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007506293

Ebook Edition © April 2015 ISBN: 9780007506309

Version: 2015-03-04

For Patrick O’Donnell and Dr Gary Colner with much love.

Contents

Cover (#u4fc9011d-a3e0-584e-913f-42e8f820c8c2)

Title Page (#u71a3cf70-90bd-5810-8682-c961904a2a0c)

Copyright (#u1ba638db-8d2d-5be0-a84b-7f2108005c16)

Dedication (#u2f840046-409f-5774-ade8-e7afcb75667b)

Chapter ONE (#uf6d70281-b393-5fcd-802f-574f4b240295)

Chapter TWO (#u46291623-2341-51de-93c7-40b9ffc9a484)

Chapter THREE (#u7d2bcbff-a075-58a7-a668-b66c5978a55e)

Chapter FOUR (#u4cbd1659-abcf-50ef-8a57-0c86ed757a48)

Chapter FIVE (#u0490abb0-2f47-570f-a227-334bfe974920)

Chapter SIX (#ue803a0b3-23c0-5cae-aba5-fafba3d3a214)

Chapter SEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter EIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter NINE (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter TEN (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter ELEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter TWELVE (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter THIRTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter FOURTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter FIFTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter SIXTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter SEVENTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter EIGHTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter NINETEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter TWENTY (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter TWENTY-ONE (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter TWENTY-TWO (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter TWENTY-THREE (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter TWENTY-FOUR (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter TWENTY-FIVE (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter TWENTY-SIX (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Churchill Angels Ad (#litres_trial_promo)

Wave Me Goodbye Ad (#litres_trial_promo)

A Christmas Gift Ad (#litres_trial_promo)

Churchill’s Angels Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

W6 Ad (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Ruby Jackson (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

ONE (#u77d79044-eb05-512a-a8bd-13e98873a06b)

April 1942

‘It’s still so strange not to see Daisy sound asleep when I wake up early, Dad. The house is so quiet; when will it feel normal?’

Fred looked up from the front page of the Sunday paper. ‘When it is normal, pet, and your mum and me is hoping that’ll be soon. You’re an absolute godsend, our Rose. Kept your mum sane, you have.’ He went back to the lead article.

Rose stood quietly for a moment. Was this the time to say something, to say that she had been thinking for rather a long time that she needed a change, a chance to do something different? Could she say, ‘Remember in February when I had a bad head cold and didn’t go to evensong? Remember I caught Mr Churchill on the wireless, heard the whole thing, instead of catching just a bit as usual? I thought then – I’ve got to do something more, like Daisy and the others. When this war ends I’d like to have done something besides factory work’? She looked over at her father, relaxing in his armchair, his waistcoat for once unbuttoned, and decided not to disturb his one morning of relative peace and quiet.

She folded up the section of the Sunday paper she had been reading and almost slapped it down on the little table between them, inadvertently causing her father to jump. ‘Sorry, didn’t mean to do that. I’m off for a run. Nothing but doom and gloom in the Post this morning.’

‘Don’t forget Miss Partridge is taking her Sunday dinner with us – suppose we’ll have to call it “lunch” since it’s Miss Partridge – so don’t be late.’

Rose promised she wouldn’t be and, after changing her ‘going to church clothes’ for something suitable for running, she hurried away. Effortlessly, she jogged out of the town, past houses where heavily laden and sweetly scented lilac trees leaned over garden walls, tantalising passers-by with their perfume; past Dartford Grammar School, where she pretended not to see the enormous reserve water supply tank, which had been installed the year the war broke out as one of the many preparations for conflict. Would an enemy aircraft bomb it and flood the many lovely gardens in this part of the town? She hoped not. Since May of the year before, England had been experiencing a lull in the bombing raids from Germany and from the closer German bases in occupied Holland and France. But the worst part of a lull was that one never knew when it would end. In some ways this uncertainty was worse than nightly attacks. At least then people knew what to expect.

Rose changed direction to run through Central Park, formerly a favourite meeting place for local residents, especially on Sundays when families strolled among the flowerbeds. These days anxious parents preferred to stay at home rather than take a Sunday walk with one eye always on the sky and ears straining for the threatening sound of aircraft. Out of the park she ran, further and further into the countryside, now carpeted with spring flowers. She wondered if she had ever seen such stretches of golden buttercups; they were everywhere. Who could not feel happy just by seeing them? Fruit trees, too, showed off their mantles of pink or white blossom as they swayed in the gentle breeze. Who could believe that this glorious garden could possibly be a small part of a huge battlefield?

Rose began to run towards the river, revelling in the feeling of absolute freedom, enjoying stretching her long legs. She stopped, not because she was tired or stiff but because she wanted to stand still and breathe in the clear air. How absolutely beautiful it was. Everything was perfect. The blue sky was decorated with the remains of white vapour trails, showing where aircraft had passed. In the fields below and around her, green shoots were poking up through the soil and, some distance away, untethered horses were grazing. Smiling, Rose pretended that there was no war; there had never been a war and all was well with the world. She decided to run as far as Ellingham ponds, those little man-made pools that had been created when gravel and sand quarrying had stopped just before war had broken out. Horses had drunk from them; migrating birds or local wildfowl had nested there. The ponds were hardly objects of beauty now: every one was camouflaged with wire netting on a floating wooden frame, so that German airmen, sent to destroy the nearby Vickers munitions works, could not use reflections from the water as an aid to navigation.

Eventually she came to a halt, remembering that Miss Partridge was coming to Sunday dinner. Heavens, being late will certainly spoil a perfect Sunday, she thought as she began to trot slowly back along the way that she had come, and I do want to see Miss Partridge.

She reached the rather rough road that wound its way across the area, and was about to quicken her pace when she heard the sound of a speeding motorbike. It sounded as if it was on this country pathway. What an odd place to ride a motorbike, Rose thought as she jumped off the pathway and onto the wide grass verge.

Rose’s older brothers had taught her to drive before she left school at the age of fourteen, and she was accustomed to delivering groceries in the family van, but their parents had never allowed either of their twin daughters to ride a motorcycle. ‘They’re too heavy for girls,’ Sam, their eldest brother, had agreed. ‘If you can’t lift it, you shouldn’t be riding it.’ Nothing the girls had said had persuaded him to change his mind.

The roar of the engine grew louder and closer. Rose moved further back on the verge, noting, with growing concern, both the poor surface of the road and the sound of the accelerating bike. Before she could think another thought or move a muscle, the bike was there and then…was gone.

‘Wow. Fantastic, what a speed, lucky—’ Rose began aloud, just as she heard a screech of brakes, followed by a thud. She listened but there was nothing but a terrifying silence.

For a fraction of a moment, she felt rooted to the spot, but the adrenalin lifted her out of the almost trance-like state and Rose Petrie, former junior sports champion, began to run. She was round the corner in moments. The motorbike was lying on its side across the pathway. Her stomach lurched in horror as she saw the driver pinned underneath. Rose kneeled down beside the machine and tentatively examined the unconscious man. How young he was, and how very, very still. His eyes were closed and there was severe grazing on one side of his jaw; blood was seeping from a wound in his forehead and mixing horribly with the dirt and gravel on his face.

Rose had no idea if he was alive or dead. She remembered her brother’s words – ‘If you can’t lift it, you shouldn’t be riding it’ – and wondered if it would even be wise to attempt to lift the machine off the young man’s body. Should she try somehow to clean his poor face? Water? In the wonderful films she had seen with her sister and their friends, the wounded hero was always given a sip of water. If she ran back to one of the ponds perhaps she could manage to wet a cloth, but she had no cloth. She looked again at the motorcycle, which was possibly crushing something important while she hesitated. Rose seemed to remember that any implement sticking into the body of an injured person should not be removed until qualified medical personnel were on hand, but what was she supposed to do with a machine that might well be crushing this man to death?

Thank God, Rose thought as she felt a faint pulse in the neck. Could he hear her if she spoke, and would that help him? ‘I’m going to try to move your bike,’ she said as calmly as she could. Oh God, what if I drop it back onto him? ‘I’m really very strong,’ she continued, hoping against hope that her low voice was reaching him, perhaps giving him some comfort. ‘I work in a munitions factory and lift machinery every day. You wouldn’t believe how heavy some of that stuff is.’

There was no response and so Rose stood up, took a deep breath, bent down, grasped the body of the bike firmly, and, having assessed in which direction to move, began to lift. The trapped rider groaned. He’s alive, he’s alive. I can do this. In another moment she had the bike on the grass verge. She wanted to fall down beside it, as every muscle in her well-toned body seemed to be complaining, but instead she looked for something with which to wipe the blood from his face.

Why did I change? She was wearing only a shirt and her shorts. Then she heard a voice, faint but clear.

‘Help me.’

Immediately she was back on her knees beside the injured man. ‘I’m going for help,’ she said. ‘I wish I could stay with you but there’s no one else here.’ She was pulling her shirt out of her shorts. Desperately she tried to tear off the bottom but the material resisted.

Rose looked around and her eyes lit up as she saw a large shard of glass from the broken headlamp. She picked it up and feverishly sawed at the shirt. At last there was a tear, which allowed her to rip it apart.

Praying that it was clean, she folded it and gently wiped the blood from the man’s face. ‘I wish I could do more for you but I’ll get help…’

The whisper was so faint that she had almost to put her ear to his damaged face. ‘Dispatch. Pocket. Urgent…Take.’

Again Rose looked round, hoping desperately that someone – anyone – was within hailing distance. No one.

She felt a touch on her hand. ‘Please.’

‘Of course, I’ll do what I can.’ With a hand now marked by his blood she tried the pocket of his leather jacket. Nothing. ‘It’s a dispatch. An inside pocket. Do you have…?’

His eyes blinked as if answering her. Rose reached inside his jacket, hoping that she was doing no damage to his poor body. There was a pocket, and inside was a fairly thick envelope. ‘Got it,’ she said. ‘I’ll run for help and then deliv—’

The eyelids fluttered again and the voice was fainter than before. ‘Urgent. Please.’

‘I’ll do it. Trust me. I’ll get you some help. Trust me,’ she repeated. ‘I’ll deliver your letter and I will bring help.’ As she spoke the last words she was already running. She had not run competitively since she was a schoolgirl, but she was fit and well. She tried to forget the injured, possibly dying dispatch rider, and the message that seemed to be burning a hole through her shirt. She had read the word on the front. ‘SILVERTIDES’. She knew the name only because she had occasionally delivered tea to the kitchen door of the great house. It was at least three miles away and she had a single mode of transport – her long legs.

Rose kept going. As she ran she remembered the words of her coach from those long-ago school days. ‘Long and longer strides for the first twenty paces; then accelerate until you think you can’t go any faster. Relax facial muscles.’ She almost flew, her long stride eating up the uneven ground. She tried not to think of the letter she was carrying, or the dispatch rider who had insisted that he be left, possibly to die, in order that the dispatch might reach its destination. The young man was in the military and was obviously about the same age as her brother Phil.

Twenty-three is too young to die, she thought fiercely, remembering the loss of her brother Ron, who had been even younger when he had given his life for his country.

‘Empty your head, girl, empty your head,’ came the order from the long-ago voice, and obediently Rose forced herself to concentrate on nothing but finishing the race.

She ran as she had never run before, oblivious of her screaming muscles, her labouring breath, her tears. Heel, outside of foot, rock off with the toes, over and over again; push with your ankles, drive with your elbows. For a moment she was in a bubble as she pulled remembered advice up from her subconscious, which helped her think only of technique and not of injured dispatch riders or important messages.

Ahead stood the gates of Silvertides Estate. With her last ounce of energy she reached them, clung to the bars to prevent her body sliding, exhausted, to the ground, and pressed the bell.

‘Don’t fuss, Mum, it was no more than a cross-country run.’

Rose had had a refreshing bath and was now sitting in the scrupulously tidy front room, not the kitchen, so seriously had her parents taken her story of the afternoon’s events. Of course she had been much too late for Sunday dinner and was now pressingly aware of growing hunger.

‘Quite an adventure, our Rose, but your mum and me think you’re making light of it.’

‘’Course not, Dad. Only sorry I missed Miss Partridge.’

‘She said the same about you, love, but she’d promised to do geometry or some other maths subject with George – sharp as a tack is our George.’

Delighted to have young George Preston’s prowess become the subject of discussion, Rose congratulated her father again for taking in the orphaned youngster, who had initially caused the family a great deal of bother, culminating in vandalism and an attack that had put her twin sister, Daisy, in hospital.

But Fred had had years of experience in dealing with daughters who did not want to be the focus of his attention. ‘Come on, Rose. Rose ran, Rose saw accident, Rose helped injured rider, Rose delivered letter. Rose came home. There has to be more to it than that.’

‘Aw, Dad,’ moaned Rose, using exactly the tone of voice she had used as a disgruntled child, ‘he was speeding on a poor surface and a pothole caught the front tyre. He and the bike went up in the air – I think, I didn’t see it – and the bike landed on top of him. He asked me to deliver his dispatch and I did. Possibly I spoke to a butler sort of person, quite grand and with a posh voice, but he said not to worry, it was in their hands. I sat in a lovely room and a maid brought me tea; they’ll have got an ambulance…can’t be sure.’

Is he alive? Did they find him? They had promised to go immediately and they said they would get him a doctor.

A long-ignored memory surfaced. This was not the first time she had run for help. She had tried to black out all memory of that day on Dartford Heath, when Daisy had stayed beside two unbearably sad, dead bodies, and Rose, the faster runner, almost traumatised by shock and horror, had conquered her threatening hysteria and run for help.

‘Didn’t want to warm it too quick, Rose; nothing worse than dried-up food. Eat that up and then off to bed with you or you’ll never do your shift tonight.’ Her mother had come in from the kitchen at just the right moment, for Rose wanted to be left alone to think.

Sitting in an armchair in the front room with a plate of food in her hands took her straight back to childhood. Unwell? Unhappy? Either situation could be mended by sitting in a comfortable chair in the front room, eating a plate of Mum’s best stew. Not that this stew could measure up to the ‘before this dratted war’ stews; far more vegetables than meat – thank goodness carrots were not rationed – and a gravy Mum was near ashamed of. But so far the Petrie family had managed to avoid tinned stew. ‘Can’t be sure what’s in it,’ muttered Flora as she arranged the tins on their grocery shop shelves.

As she ate her lunch, Rose could remember nothing but the face of the dispatch rider and the feel of the gates at Silvertides as her exhausted body collapsed against them. Maybe it would all come back tomorrow. She wondered if she would ever find out about the injured rider. She knew enough about dispatch riders to realise that she would never learn what was in the so-vital letter. But it had to be really important. His face swam before her tired eyes and his voice whispered, ‘Urgent, please.’

I tried, she thought to console herself. I hope it was enough.

Two days later Rose was standing at her workbench on the factory floor. She was dirty and hungry and very, very tired. More than anything she longed for the shift to be over so that she could go home.

Rose’s shift supervisor appeared at her bench. ‘Petrie, got a minute? Boss wants you in his office.’

‘What’s wrong, Bill?’ Rose could think of no reason for a summons to the office.

‘He’ll tell you hisself and that’ll save me guessing, won’t it?’

Rose straightened up, took off her overall and the scarf that covered her hair, and walked off to the office, where she hesitated before knocking on the door.

‘You sent for me, Mr Salveson,’ she said, noting that as well as her boss and his secretary there was a second man in the room.

‘Come in, Rose. Mr Porter here would like to talk to you.’

Vaguely Rose felt that she knew the second man but could not place him. ‘I don’t understand, Mr Salveson.’

‘The local newspaper would like to talk to you, Miss Petrie, about your wonderful action in delivering the dispatch for the gallant boy who died trying to do his duty.’

Rose was speechless. The secretary saw the colour drain from her face and shouted in time for Mr Salveson to catch Rose before she fell to the floor. He lowered her into a chair and gestured to his secretary to fetch a glass of water, which he held to Rose’s lips.

She pushed it away. ‘Dead? He died?’

‘Yes, one of our stringers heard about it. The housekeeper at Silvertides told us how you ran with it. Seems his lordship had to go back to London before he could talk to you.’

Rose forced herself to stand up. ‘I’d like to go home now, Mr Salveson.’

‘We need an interview,’ said the reporter.

‘No,’ said Rose quietly, and looked at her employer.

‘Are you sure, Rose? People should hear about your courage.’

Courage? What courage had she needed to run a few miles with a letter? The boy, the dead boy, had had courage. ‘I won’t talk to the press, Mr Salveson, and the hooter’s gone.’

‘You heard her, Porter. Miss Petrie doesn’t seek publicity. I’ll drive you home, Rose. I can see you’ve had a bit of a shock.’

‘No, thank you, Mr Salveson. I’ll be fine with Stan Crisp. He’ll see me home.’

The disgruntled reporter left angrily and Rose went to catch her friend, Stan, before he headed off in the opposite direction. Really she wanted to be alone, but she could not be sure that the reporter would not follow her. If he did, she knew that Stan would not allow him to bother her. She did not tell him the whole truth, merely that she felt faint and would feel better if he was with her.

She always felt better when Stan was there.

TWO (#u77d79044-eb05-512a-a8bd-13e98873a06b)

May 1942

‘Stan, won’t you please come to the spring dance with me?’

Stan looked across the table at Rose and sighed.

‘Stan?’ she persisted unhappily.

‘Yes? Sorry, Rose, I thought you were going to ask someone else. Charlie’s a good dancer. Why don’t you ask him?’

‘I have asked, and everyone is either working that night or has already got a partner.’ She looked down at her hands, afraid to meet his eyes. ‘Why do none of them ever ask me out?’ She smiled then, thinking that she might have found the answer. ‘Is it because they think we’re an item?’

Rose, Daisy and Stan had started school on the same day and had been friends ever since. Rose and Stan had always been particularly close, and Stan’s grandmother, with whom he had lived since his parents had died in a flu epidemic, always referred to Stan and Rose as the perfect couple.

‘Now that we’re grown up, we’ll have to ask your granny to stop matchmaking.’

Stan looked around the room, as if hoping he might find an answer to her question written on one of the walls of the ancient tavern. He straightened his backbone. ‘It’s not Gran, Rose. Can I tell you the truth?’

‘I’ve got bad breath? For goodness’ sake, Stan, what is it?’

‘You scare everyone to death, pet, simple as that. Blokes don’t want to be second best – all the time.’

‘Scare everyone, me? How? And if I do scare everyone,’ she said, her voice heavy with sarcasm and throbbing with hurt, ‘why don’t I scare you?’ She stood up as if to leave.

‘Sit down, Rose,’ said Stan gently, and he pulled in her hand. ‘Maybe I should have said something years ago, but I like you just the way you are, and…’ he hesitated for a moment and then jumped in, ‘more importantly, I know that the right man for you will love you just as you are.’

‘Thank you very much, I’m sure.’ Rose felt physically sick. Stan, her oldest friend, the man she had got so used to being with – what was he saying?

‘Rose—’ he began, but she gave him no time.

‘The right man?’ she repeated angrily. ‘The right man? Not you, then. So will you please tell me what’s wrong with me? Ivy Jones has dated every man in Dartford and she hasn’t a single brain cell in her fluffy little head.’

‘She knows how to talk to lads—’

‘And I don’t,’ she interrupted him. ‘I’ve been talking to lads since I first opened my mouth.’

‘You talk like you’re a lad, Rose; comes of having three brothers.’

Rose looked at him quizzically; she did not understand what he was saying.

‘You want me to pretend that I know nothing about football? And I mustn’t be caught changing a tyre on my dad’s van? If that’s the case, why is it that every single last one of our friends has been more than happy to have me change tyres, replace fan belts, cheaper than the local garage…? I could go on.’

Damn. He had hurt her and he could think of nothing to say that would improve the situation, but he was her friend and he tried. ‘You run faster, jump further, climb higher, swim better; dash it, Rose, if they let girls play football you’d be everyone’s favourite centre-half, and more than one of us has said as how Sally isn’t the only girl in our class as could’ve gone to a university. And now your picture’s been in the paper about trying to save that dispatch rider. My gran was hurt you didn’t tell her so she could buy the paper. But never mind that; you had your reasons for keeping it quiet. That was just like you, Rose. That’s what I mean. The things you do. Nobody measures up, Rose. We all love you, but you’re too good for any of us. You should join up, you should, and have a chance to meet other men. I’m going to enlist as soon as I can; still got to convince my gran.’

She looked at him in astonishment. ‘One, there isn’t a picture in the paper because I told the reporter to go away.’ She took out her hankie, a very pretty one that her friend Sally Brewer had given her last Christmas, and blew her nose. ‘And two, what do you mean, enlist? Why? You’re doing war work – have been since you were fifteen.’

‘Not enough, not when there’s lads out there willing to get killed for us; lads like your dispatch rider, and your brothers. And you talked about it, Rose, before Daisy went.’

‘I can’t compete with Daisy. Are you scared of her too?’

Stan ran his fingers through his hair in obvious exasperation. ‘Maybe if I hadn’t left school at fourteen I’d have learned the words to explain. It’s not just the things you’re good at; it’s more than that, but I can’t say exactly. But somewhere there’s the right bloke, Rose – maybe in Dartford, maybe in London; maybe, like for Daisy, in one of the foreign countries. Hanging around with me won’t help you find him.’ A huge grin creased his pleasant face and he punched the air with his hand. ‘League, that’s the word, like football teams. I’m right fond of you, Rose, but I’m not in your league.’

Again Rose got to her feet. She hadn’t really wanted to come to the Long Reach Tavern as it was unpleasantly close to where the motorcyclist’s accident had occurred, but it had always been one of the favourite places of their intimate group and she would have found not wanting to go difficult to explain. ‘I want to go home, Stan. Expecting a letter from Sam or Grace. Don’t enlist without telling me, will you?’

‘I won’t,’ he said – but behind his back he had his fingers crossed.

Rose’s heart seemed to feel a slight pang. For the first time in their relationship, he was unable to meet her eyes. ‘You won’t tell me, or you have enlisted already?’

‘I wanted to tell you first thing but the right words wouldn’t come.’

She stared at her oldest friend, hurt and anger warring with each other. ‘Then let me help you. “Rose, guess what. I’ve enlisted in the XX.” That help?’

She turned and almost ran from the room, and Stan felt in his pockets for some loose change which he threw down on the table before hurrying after her.

Her bicycle was gone and there was no sign of her on the path. Stan wheeled his own machine towards the road, shaking his head in exasperation. Over fifteen years of friendship, and few cross words, but with a couple of ill-thought-out sentences he had blown it. He began to pedal towards Dartford. He knew he would never catch her – unless she wanted to be caught – but he cycled as quickly as he could, hoping that she would have waited for him somewhere.

Rose cycled home, thoughts whirling around in her brain as furiously as the wheels on her bicycle. Not in your league…the right man…joining up.

‘You’re not the only one who can join up, Stan,’ she yelled, to the world, though pleased that there was no one within hearing distance. ‘You’re not the only one who feels second best, even though no one has ever refused to take you to a dance.’ Conveniently she forgot that Stan had a shift on the Saturday evening.

When she had gone far enough that she knew he would be unable to catch her, she got off her bicycle and sat down on the rough grass. She tried to rub away the tears but they kept falling. Stan doesn’t love me; what’ll his gran say? She wants us to marry; I know she does. Scared? Those great big lads are scared of me? Me?

As the enormity of what Stan had said really struck her, Rose cried great broken sobs. After a few minutes she pulled herself together, sniffed loudly, blew her nose on the end of her shirt and stood up.

‘You’re not the only one who wants to do more with your life, Stan Crisp. Rose Petrie does too and, watch out, she will.’

*

‘Enlisted?’

‘Yes, Mum.’

‘No.’

The small word seemed to echo around the kitchen, even bouncing off the clean white walls, before finally disappearing in a sigh.

‘No,’ repeated Flora Petrie, staring in distress at the only one of her five children still at home. ‘You don’t mean it, Rose, you can’t. Are you doing this because of a tiff with Stan? We knew he’d been at army recruiting; we hear everything in the shop. We wasn’t sure whether to tell you or not. It was between you and Stan, we decided. But hear me out, Rose: you’re already doing more than your share in the factory. And remember, you was bombed, you ended up in hospital. Not to mention delivering that dispatch to some admiral or general or something at Silvertides. God alone knows what goes on in that house. Boats could come right up the Thames Estuary bringing who knows what.’ She ended on a sob. ‘I can’t lose you too.’

Rose fought back a tear. She had been sure that her mother had got used to the idea of her enlisting; they had discussed it so often since the outbreak of war. ‘Please, how many times do we have to go over this? Don’t make it any harder than it already is.’

Mother and daughter, equally distressed, looked at each other.

There was the sound of hurried footsteps on the stairs. ‘Flora, love, we’ve gone over this a million times. Rose has to have her chance like the others.’ Fred Petrie had come up from the family’s grocery shop, upon hearing the raised voices, to join in. ‘Come on, I need my dinner, and Rose needs hers too if she wants a sleep before her shift.’

Flora fixed on the word ‘chance’.

‘Her chance to be killed, like my Ron or that lad on the motorbike. Wonder what his mum feels like.’

Rose stood up, towering over her parents. ‘That’s it, Mum. I’ll let you know when I’m going, but I am going.’

Without another word, she walked out.

She was angry. Of course she understood her mother’s concerns – had she not lost one son to this ghastly war? Her eldest son had been a soldier, an injured prisoner of war and, finally, an escaped prisoner, now found and repatriated. Her third son was with his beloved navy, ‘somewhere at sea’, and her other daughter, Daisy, Rose’s twin, was an Air Transport Auxiliary pilot. Rose, who had worked in the local Vickers munitions factory since before the outbreak of war, had remained at home as a loving support, burying her own ambition to be, as she believed, of more value to the war effort as a member of one of the women’s services. Now, after almost three years of waiting and hoping, Rose had asked her employers to release her so that she could enlist. To say that she was surprised to have had her request granted so quickly would be an understatement. Her immediate boss had informed her that the company would write a recommendation asking that Rose Petrie be allowed to join the Women’s Transport Service, part of the Auxiliary Territorial Service.

‘We’ll be sorry to lose you, Rose, grand worker that you are, but if you want to be in the ATS then we feel it’s our duty to help you,’ said her shift foreman. ‘Mind you, we shouldn’t have had to read about the heroism of one of Vickers’ workers in a small paragraph in the local paper. Too modest by half, our Rose, and why they had to use an old school photograph, I’ll never know.’

Rose, who had refused to be interviewed or to have her photograph taken, had been unaware that the newspaper had photographs from her school sports days in their files. They had produced their article anyway, without her cooperation. She could still see nothing heroic about running for help and would have preferred it if the incident had never come to light.

‘You’d think I swam through shark-infested waters, the way they’re carrying on,’ she wrote in a letter to her sister. ‘Yes, I delivered the dispatch and I hope it was worth it, but that boy died, Daisy. He’s the hero. A hero would have been able to save him, not leave him alone to die. I can still see his face and hear his voice…’

Rose had not really expected her mother to be delighted when the letter of acceptance arrived, but neither had she expected such strong opposition. After all, it could scarcely be called a surprise. Rose loved her parents and hoped to continue to be a tower of strength to them, but it would have to be from whichever posting she was given. Her training post was to be in Surrey, a joy to both Rose and her parents as it was no great distance from Dartford. Should Fred be unable to find petrol, her parents would visit by train or, if Rose were to be given a pass, she could travel home. Rose was determined not to feel guilty: because she was looking forward with delight to being away from home, away from the cosy flat where she had lived all her life, away from the factory where she had spent several years, and especially away from embarrassing memories of Stan’s comments.

Her thoughts flew to Grace Paterson, an old school friend. Grace had simply walked out of her home and disappeared for almost a year. No one had had the slightest idea where she was or what had happened to her. Maybe I should do the same, Rose thought. Just pack my little bag and melt into the night.

Envisaging her mother’s distress if she were to do such a thing, Rose quickly changed her mind. She could never bring herself to disappear without warning. She sighed. How lovely it would be not to have a conscience. Life would be so simple.

The date had been fixed. In two weeks’ time, Rose Petrie would show herself at Number 7 ATS training centre in the lovely Surrey town of Guildford. After induction and training, she would become a fully credited auxiliary. Flora, Rose felt, would cope as she had coped with every situation this war had thrown at her.

‘It’s only down the road, Mum. I’ll come home every minute of leave I get. Maybe I’ll be able to give you a hand in the shop now and again. You’ll see. You’ll hardly know I’m not here.’

Flora pretended that she believed what her daughter was saying, while Fred explored every known avenue – and a few shady formerly unknown ones – but was unable to source extra petrol. His daughter reminded him that she was of age and perfectly capable of starting her adventure on her own.

‘For heaven’s sake, Dad, a training camp can’t be anywhere near as scary as a munitions factory, and you and Mum managed to let me do that on my own.’

‘You weren’t on your own, love; for a while you had our Daisy here supporting you.’

*

Some days later, Rose went shopping for her exciting new venture. She had been told that her uniform would be provided, and so she had packed a few changes of clothes for off-duty hours, if there would be any. Discovering the frock she would have worn to the spring dance – had Stan taken her – she pushed it to the very back of her wardrobe. She was sure she would never want to go dancing again. She was joining the ATS and would be dedicated to her work, to her new career, she decided rather grandly.

Her parents had told her to make a list of the personal items she would want to take with her. ‘You’re welcome to anything that’s in the shop, love. Me and your mum’ll be happy to pay for it,’ Fred had said, but Rose wanted the excitement of going shopping for this amazing adventure, which, even before it had properly begun, she was finding both exhilarating and frightening.

‘Stockings, pyjamas, white petticoat, white thread, black thread, darning wool, elastic – if I can find any – shampoo, toothpaste, deodorant.’ The list seemed endless. ‘Unbelievable, Mum, the list of things we can’t live without.’

‘We’ve learned to do without, lass; hardly notice any more that we haven’t seen a banana in years. Here, have a look in this,’ Flora said as she handed her daughter a catalogue. Flora hid her misery well. She would never accept that all five of her children were, as she put it, in the Forces – the four still alive, that was – but she could pretend, she hoped, until Rose was gone.

Looking at the advertisements in her father’s catalogues was an important part of searching for ‘best price’. Fred had no space on his packed shelves for deodorants but they were listed in the catalogues. Flora had found one with a catchy name: ODO-RO-NO – ‘The greater the strain, the greater the risk of underarm odour.’

Rose laughed. It practically claimed that no matter how hard she worked, there would be no unpleasant smells. ‘Not too expensive either, Mum. We’ll have a look in the town.’

Palmolive soap was listed at thruppence ha’penny per bar and Rose decided to buy two or three bars, if possible. Soap had been rationed in February, as fat and oil had been deemed more necessary for food production than for cleanliness.

‘I’m sure we has some Lifebuoy soap in the flat. I been saving mine,’ Flora offered. ‘We has to take your coupons for soap, love; iron-clad rules, your dad has.’ She looked at the items heaped on her daughter’s bed. ‘Is there anything left that hasn’t been rationed, love?’

‘I expect chocolate, sweets and biscuits will be on the list before long.’

‘Best to stock up on what’s available. Your dad hears rumours when he goes to the distribution centres.’

Rose smiled. ‘Every Saturday since I’ve been old enough for pocket money, I’ve bought a tube of Rolos. Could I survive without them?’

Flora, who ate few sweets but was, she had to admit, a little too round, looked with affection and a little envy at her tall, slender daughter, who ate everything and anything and yet never gained weight. ‘’Course you could; we gets used to anything after a while, but as it happens there’s some Rolos in the shop and I could put some in a tin for you so they’ll keep.’

Rose’s wage was not going to be quite as much as she had earned in the factory and so she would be compelled to be more frugal – and she’d have no parents there ready and willing to hand over the odd shilling ‘till the end of the week’.

She had seen nothing of Stan since she had left the factory and there was an unaccustomed dull ache in her insides. None of the lads fancy me, she told herself, not even Stan. Daisy knocks them down like skittles and we’re twins. What’s wrong with me?

Try as she did, she could not understand what Stan had tried to tell her. ‘Not in her league’, indeed. What a load of old tripe. Was it possible that Stan had palled with her because no one fancied him? No, Stan wasn’t like that. She had written to Daisy about it and Daisy had tried to console her.

You and Stan have been friends for ever and friendship is very important. He does love you and I think you love him the same way, as a dear and special friend. Don’t let go of that, Rose. Tomas is my friend, but our love for each other is so much more than that and you’ll know it when it comes. It’s like being run over by a Spitfire, knocks you for six. Absolutely wonderful.

‘Thanks a lot, Daisy, I don’t think,’ Rose had said angrily, and got on with her packing.

It was young George who brought her news of Stan. She had gone down to Central Park for a last walk round and bumped into her foster brother on his way home.

‘Got a letter for you, Rosie,’ he had said with a cheeky grin.

‘Rose, not Rosie, you horrible little boy – and how come you’ve got a letter for me?’

George had lived with the Petries since his mother and brother had been killed in an air raid. Nothing had been heard from his layabout father since and, frankly, no one missed him. The two years of regular food and sleep, plus affection and guidance, meant that the boy was completely at ease with all the Petries, and he merely laughed. They walked along together companionably while he searched through his pockets. ‘Got it last night but you was in bed when I got back from the pictures and you was up before me this morning. Now where can it be?’

‘If this is some kind of a horrible boy joke, I will tie you to my—’

Eventually George hastily pulled out the rather grubby, crumpled envelope before Rose could think of something nasty to do to him. ‘Here,’ he said with a grin. ‘Your chap kissed it lovingly, made me want to be—’

‘You have no idea how sick you’ll be if you utter one more word, Georgie Porgie.’

George was bright in more ways than mathematics and he handed over the letter and walked sedately beside her. ‘Blimey, Rose, you’re not going to wait till we get home. Maybe he wants a quick reply.’

‘Then he can wait,’ muttered Rose, and she began to stride out so that, fit as he was, young George was no match for her speed and had to trot to keep up as they rushed home.

Once inside, Rose hurried up the stairs that led from the family shop and from the back door she called, ‘I’ll be there in a minute, Mum,’ and went into her bedroom, closing the door behind her. She flopped into the old chair that had worn the same flowered cotton cover for as long as she could remember. For a few years she and Daisy had been able to sit in it together comfortably, but as they’d grown they’d had to take turns – one in the chair, the unlucky one on the bed. Since her twin had gone off to join the ATA, Rose had been able to make constant use of the chair, which made her miss her sister more than ever.

‘Well, let’s see what Stan has to say, Daisy,’ she said aloud.

The letter had been written the day before and had Stan’s Dartford address on it.

Dear Rose,

I have joined the army. I’m the lowest of the privates in The Queen’s Own Royal West Kent Regiment. I never meant to hurt you, never. You’re my best friend, have been since we was five. That’s a long time and I don’t want nothing to spoil it. I love you, Rose, can’t think of another word for what I feel but I do know it’s not the love that you need for marriage. Please write to me because if I’m going overseas…

Please understand, Rose. I don’t know. Maybe it was them Spitfires sent out to help the people in Malta and every last one of them bombed to bits before they could even get off the ground. Maybe it’s these raids on lovely bits of England. Gran took me on a trip to Bath once – couldn’t believe it was real and now thousands and thousands of buildings is damaged. Gran’s right cross about Bath and about me joining up but I’m making her an allowance, same as I give her now. She’s not old, Rose. I suppose you always think your gran is old but she’s not and the neighbours both sides say they’ll keep an eye on her. She’ll always know where I am. I’ll write to both of you when I can.

George said as you have joined up too. I bet you’re in the ATS and one day we’ll see you driving all them famous people around London.

Love,

Stan

Oh, Stan, I know, and I love you too.

There was a PS, but he’d very effectively scored it out. Rose tried to decipher it but could make nothing of it. She got out of the chair and lay down on the bed. Stan was gone, and unless his grandmother had his address she would have to wait until he wrote to her – if he ever did. At least she could get a letter written and Mum or Dad could get the address when Stan’s gran came in for her rations.

She got up, found her writing pad and started writing.

Dear Stan,

I’m ashamed of myself. Imagine falling out over a dance I never really wanted to go to anyway. Stupid.

You’ll be a great soldier. I am very proud of you and I bet they make you a general. I hope the West Kents have a nice uniform.

I think I’ll be going away soon too. Don’t worry about your gran. With the neighbours and Mum and Dad, she’ll be all right.

Please answer this,

Your friend always,

Rose

She stood up, sniffed, wiped her eyes which had gone all teary, tidied her hair and went downstairs to join what was left of her family.

THREE (#u77d79044-eb05-512a-a8bd-13e98873a06b)

Guildford, Late May 1942

‘Think yourselves lucky, girls. When I joined the ATS we were definitely the military’s poorest relation. Some of us were without a uniform for months and had to wear out our own clothes, and I do mean wear out. The ATS is not a stroll in the park. If we were lucky we got a badge. Three years later and you’re getting everything, including your knickers.’

‘Which no woman in her right mind would want to wear.’

‘Very funny, Petrie, or was it you, Fowler? Maybe they’re not Selfridges’ best but, believe you me, you’ll be glad of them in the winter.’

Rose, who had been standing quietly among the new recruits or auxiliaries, as ordinary members of the Auxiliary Territorial Service were now called, said nothing but merely waited till she was given her uniform. She had made no remarks, no matter what the commanding officer thought. Her stomach was churning with excitement that she was to be – at long last – an actual servicewoman.

‘Hope we have your size, Goldilocks. You’re tall but you’re slim. Any good with a needle?’

‘Not very, ma’am, but my mother is.’

‘And did you bring Mummy with you?’

Rose blushed furiously, but contented herself with reflecting that she could, if so inclined, pick up this bossy little bantam and toss her in a wastepaper basket. She said nothing and watched the separate pieces of uniform pile up on the table. A lightweight serge khaki tunic was joined by a matching two-gore skirt, which she hoped would reach her knees, two khaki shirts and a tie. Slip-on cloth epaulettes with the ATS logo stitched on followed the battledress trousers, which the new controller had insisted upon as being much more sensible for the work the ATS auxiliaries were called upon to do, preserving modesty in some cases and simply being more comfortable in others. A cap, some unbelievably ugly green stockings, khaki knickers that were, if possible, even uglier, heavy black shoes and robust boots completed the pile.

‘I’ve given you the longest items we have, Petrie, but I’m afraid they’ll all be too loose.’

In some despair, Rose spoke tentatively. ‘Didn’t the army expect tall women, ma’am?’

‘Of course women of all sizes were expected, and I myself have dressed at least three over the years who were much taller than you, Petrie; at least six feet in height, and broad too. I’ll keep my eyes open for items that will fit a little better, but in the meantime there are several seamstresses who’ll be happy to help out. In fact we have one auxiliary who did tailoring at an exclusive address on Bond Street in London. Look at the notice board in the canteen. Names and units are there.’

The group, having received their issue, returned to the rather Spartan hut that they were to live in for the foreseeable future. It contained iron beds, some cupboards, a few chairs, and a picture of Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of the President of the United States, who had toured the camp in August.

‘Shouldn’t she be in the lecture rooms with the King and the PM?’ Rose asked, but no one answered, being too involved in comparing uniforms.

Rose was not a vain woman, personal vanity not having been encouraged by the Petrie parents, but when she saw herself dressed in uniform for the first time, she wanted to weep. The tunic was wearable if she tightened the half-belt at the back till it was almost nonexistent, but the skirt, although long enough, was so loose that it fell down, leaving her standing in her new knickers. Since leaving school, only her twin sister, Daisy, or their mother had seen Rose in her underwear and she was embarrassed.

‘Why did I ever leave Dartford?’ she said aloud. The uniform looked so unprofessional and, although she was at a base in Surrey, which was not too far from home, the new intake had been told not to expect leave for some time. Were she to post the absolutely necessary items home, it could take weeks for them to get there, be altered and be sent back.

‘Don’t worry, Rose.’ Another girl, whose name she had not yet learned, came over from her bed. ‘I’ll take the skirt in for you after tea, and they’ll all be here to admire the stunning new khaki issue, so try to take it in your stride. With those blue eyes and that glorious golden hair, the colours will suit. And as for modesty, three months at a boarding school and you wouldn’t have an inhibition left. That’s about all I learned, apart from a bit of sewing – both skills equally useful in the ATS.’

‘You’re very kind. I can sew on buttons, jobs like that, but—’

‘Always better to leave it to the professional. I’m Cleo Fitzpatrick, by the way, which is, believe it or not, short for Cleopatra. My father was stationed in Egypt when I was born; I still haven’t discovered a really good way of paying him back.’

Rose, who had a very happy home life, looked at Cleo’s face and relaxed as she saw that the girl was joking. She was obviously as fond of her parents as Rose was of hers. ‘My twin sister and I always hated being called after flowers.’

Cleo looked up at Rose. ‘But you suit your name, and what about your sister? Are you identical?’

Before replying, Rose reached for her shoulder bag, took out her purse and retrieved a small black-and-white snapshot taken on the beach at Dover before the war. ‘I’m obviously the giant looming over two of the others, but which one d’you think is Daisy?’

Cleo examined the picture for some time. ‘None of them even has the same eyes or hair. That one maybe, the taller one.’

‘That gorgeous creature is our friend Sally. The sweet little one in gingham is my twin sister.’

‘No, you’re not serious.’

‘Cross my heart. She’s in the ATA, believe it or not, and a pilot. Been in since ’41.’

There was no time for further chat as several other girls poured in. ‘Quick, you two, the boiler’s on in the washhouse. First come first served.’

The accommodation on this training base was basic. It consisted of huts of all shapes and sizes. The toilet block was a long rectangle built over a pit. A slight wall separated each toilet, but at this time there were no doors. Girls like Cleo who had spent years in boarding schools and were used to dressing and undressing in front of other girls were much more relaxed about this situation than those who had been raised to keep all matters of personal hygiene private. Rose hated it and longed for the day when her induction period was finished and she would be transferred, she hoped, to more comfortable living quarters. There was only one washhouse for the group and a limited supply of hot water was available, and only in the evenings. The new auxiliaries soon worked out a rota system – ‘another thing boarding school taught,’ said Cleo.

The oldest auxiliary in Rose’s hut was a thirty-eight-year-old widow from Derby, who told the others that she had joined up when her twenty-year-old son had insisted on joining the army.

‘“Join the army and see the world, Mum,” he said, and I, tears streaming down my face, begged him to reconsider. He’s all I got in the world, see, but – “I got a chance to do something grand, Mum,” he said, “and, just think, I’ll be able to give you a bit of a hand. All my food’s provided, and my uniform, plus I get paid. You’ll see, we’ll be able to put a bit aside for that cottage you’ve always wanted. The war’s an opportunity for them as is willing to take it.”’

Chrissy Wade explained her situation to the girls during a welcome break. ‘An opportunity to get killed is what I told him, so what could I do but join up? Had a cleaning job afore the war and a lot of opportunity there was there, I don’t think. Hope this lot don’t give me all the cleaning to do in the ATS.’ She had laughed then, and the younger women laughed with her, already liking her spirit.

The others were, like Rose, in their twenties. They included waitresses, beauticians, seamstresses, shop assistants, factory workers like Rose, and even two university students: Cleo, and a shy, rather intense girl from Poole named Phyllis.

‘You two will be officers in no time,’ said Chrissy, ‘that’s what my lad said. Ten lads signed up with him and one went straight for training to be an officer.’

‘I hope not,’ said Cleo.

‘You couldn’t be an officer, Cleo,’ Rose teased her. ‘How embarrassing for the ATS to have an officer with two left feet.’

‘Don’t officers just stand looking rather splendid while the others march?’ Phyllis, who hardly spoke, surprised them all by joining in.

It was obvious to Rose that Phyllis was joking, but most of the others seemed to take her remark seriously. Except Cleo.

‘That lets you out too, Phyllis. You’re too small to be splendid.’

‘Thanks very much. I’ll remind you that Queen Victoria was small.’

‘Like a little Christmas pudding,’ Rose surprised herself by suggesting. Everyone laughed.

The trainees were up by seven o’clock, their sleep having been somewhat disturbed by the almost constant droning of aircraft. Rose, like thousands of other people living in the south of England, had become used to the sound of planes flying overhead night after night, and she could recognise the sound of enemy aircraft.

‘They’re ours,’ she mumbled several times during the night. ‘Go back to sleep.’

They slept and woke, dozed and woke again, and by eight o’clock were washed, dressed, beds made, room tidied, and in the canteen for breakfast. Rose, who had shared the cleaning of their little shop and their homely flat above it, had hoped that cleaning would not be on her list of daily tasks.

‘I don’t mind keeping my own area clean, and I’ll clean up after myself, but I didn’t join the ATS for domestic duties.’

After breakfast came the dreaded drill. Learning to march certainly woke them up every morning. Cleo complained loudly that her boarding school had not included marching in its comprehensive syllabus. ‘Honestly, Rose, it looks so bleep-bleep simple when we see regular soldiers on the parade ground, but it’s far from easy. And that drill sergeant yelling in my ear only makes me mix up my feet. I’d do better if you were teaching it. Why do we always have to be bullied by men? Makes something in me rebel. But right now I’m thinking of drawing a great big R on one of these ghastly, clumpy shoes.’

‘Just make sure it’s on the right, right shoe,’ teased Rose.

In a way, however, Rose agreed. Would they ever learn to keep in line, stay in place, to use the correct foot or the proper stride, especially since they were of varying heights? Could they possibly master standing to attention, standing at ease, halting smartly when on the march, and would they ever learn to salute properly? Rose, with brothers in the Forces, found herself wishing she had paid attention when they had wanted to show her.

She was quietly glad that at school she had been on the very successful athletics team and so set herself to rapidly mastering the drills.

Aptitude tests – or trade tests, as the girls called them – came after all the marching and drilling. Scores attained in these tests would be used to decide where each ATS auxiliary would work. Rose worried that, as a working-class girl who left school at fourteen, she might be sent to work in the kitchens.

‘What do you think, Cleo? You went to a posh boarding school till you were seventeen. Some of the others have had secretarial training. You girls will get the best jobs. Girls like me will end up peeling potatoes or waiting tables.’

‘Rubbish, Rose. You have more experience in driving and in looking after cars than anyone – in our hut, at least. I learned to drive but I’ve never even put in petrol, and as for oil and keeping the blinking thing chugging along – that is all far beyond me.’

Rose laughed. ‘Don’t you have any brothers? Mine were always taking engines apart—’

Cleo interrupted. ‘And putting them back together.’

‘Exactly.’

Rose wrote to her parents during her first week of training.

If the King himself, God bless him, was to come into the camp, I would not be ashamed of my salute. But if Mr Churchill comes, and Sergeant Glover says as how he often has a quick visit somewhere, do we salute him? He’s not in the army and he’s not a royal. I’m not going to worry. Sergeant Glover knows everything.

Last night, as in two o’clock in the morning!!!!, we had a practice of what to do in an air raid. It was just an alert but it frightened the life out of most of us. We have to wear these uncomfortable steel helmets – can you imagine, steel? They’re really heavy but Sergeant Glover says they can be the difference between life and death. Don’t worry, Mum, I’ll wear mine.

Would you believe we had a talk on obeying orders? ‘Orders must be obeyed immediately and without question. Your life could depend on your ability to master this simple skill.’ Never thought I’d be grateful to have had the Dartford Dragon as my teacher in elementary school. I’ve already made a friend, although everyone in our hut is friendly. Some is quite posh and some in between, like Cleo, my new chum, who has done a lovely job of altering my uniform. You’d have cried if you’d seen me before she fixed it. I could have wrapped the skirt round me twice. The underwear is awful, can’t think why they gave it to us, unless some girls is so poor they hasn’t got changes – isn’t that a shame? – and we’ve got this huge furry coat-like thing that reaches almost to my ankles. Cleo’s trailed on the ground till she had time to fix it. She did look funny – a bit like Charlie Chaplin waddling along like a duck – but Sergeant Glover says we’ll be glad of our Teddy Bear coats in the winter.

Cleo had indeed made a beautiful job of tailoring Rose’s uniform and, as her appearance improved, so did her confidence. When she had worked in the Vickers munitions factory in Dartford, she had become expert at keeping her long hair safe inside a net; now she made one thick plait, wound it into a tight ring and fastened it with kirby grips. No matter how active she was, it stayed inside her cap.

Somehow, knowing that she looked professional made it easier for her to believe that she would succeed. Once or twice she had felt that she was struggling in the aptitude tests but consoled herself with the knowledge that she had done her best. Her ambition was to be a driver; surely the men in charge would see that she had years of experience, not only of driving but also of vehicle maintenance. She knew that driving the Prime Minister was probably an impossible dream. People say that dreams can come true but, in the meantime, decided Private Petrie, any driving would do.

She managed to go home twice during her time in Guildford. Once she took Cleo with her, worrying all the time about Flora’s nervousness around people she did not know. Her worries were for nothing. Cleo might have a retired army officer for a father and might have been educated at boarding school, two possible reasons for Flora to feel anxious, but Cleo endeared herself to Fred and Flora immediately.

‘Boarding school and then the ATS,’ sighed Flora. ‘You’ll need a good tea, pet.’

Rose and Fred exchanged an affectionate smile over Flora’s head. The much-loved wife and mother had found another lost lamb. The first one, young George, arrived home from Old Manor Farm, which was tenanted by the Petries’ long-time friend Alf Humble, in time for the ‘good tea’, and was immediately fascinated by this exciting creature with the exotic name.

‘Do you know all about the real Cleopatra?’ he asked Cleo immediately, as he munched happily into his sugarless carrot cake.

Cleo thought quickly. It was obvious to her that the boy was anxious to show his knowledge.

‘Well, I was born in Egypt and my dad said she was an Egyptian queen; I don’t know much about her except that someone rolled her up in a carpet.’

George was delighted to show her the difference between historical fact and fiction. ‘Miss Partridge told me all about Cleopatra and Julius Caesar. Do you know who Caesar was?’

Cleo had a sinking feeling that she might be doomed to spend her entire forty-eight hours’ leave reliving her secondary education. It was obvious that the boy remembered every word spoken by the wonderful Miss Partridge. ‘I do indeed, George,’ she said, ignoring the disappointed look on his thin face. ‘We could talk about Roman history but isn’t Sergeant Petrie coming tonight? He’ll want to talk to his sister, won’t he?’

Flora’s face had worn an enormous smile when she had told the girls that, hearing of Rose’s expected visit, Sam had requested – and been given – a twenty-four-hour pass. ‘He’ll be here soon,’ she said, ‘and he’ll have news of Grace and of Daisy.’

So it proved.

Sam arrived just as his father was on his way out to do his usual fire-watching shift. Fred had time only to hug his son, and say, ‘I’ll catch you at breakfast, lad,’ before hurrying off.

Cleo looked somewhat shocked as Flora brought out yet another tin. ‘Doesn’t rationing affect grocers?’ she asked, and was immediately ashamed of herself. ‘Oh gosh, Mrs Petrie, I didn’t mean that the way it came out.’

Rose laughed. ‘My parents are as honest as the day is long, Cleo, but Mum has made stretching rations into a science. In other words, when she’s expecting one of us, she and Dad do without and all rations are saved.’ She looked across at her mother, who was pretending not to hear. ‘They think we don’t know but we do.’

‘My mother’s housekeeper was exactly like that, Mrs Petrie,’ said Cleo, anxious to make reparation for her insensitive remark. ‘Probably mothers all over the country are doing without so that their children can have everything they need. Are meals still good in the army, Sam?’

Sam smiled at her. ‘Depends on where the army is. It wasn’t too good in the POW camps, except when we got Red Cross parcels. We got them from the Yanks, the Canadians, and our own. Camp I was in, we had some trouble with guards; they sometimes pinched our stuff. Mind you, I don’t think the poor beggars got much more to eat than we did. We traded with them sometimes. Everybody got cigarettes and I exchanged mine for other things – vitamin C tablets, writing paper.’

‘You got parcels from America? But they weren’t in the war then, Sam. They only joined after the Japs bombed them at Pearl Harbor just before Christmas last year.’

‘They still gave aid. Every country in sympathy with the Allies did a bit. The parcels went to a Red Cross centre in Geneva, I think, and the Swiss distributed them to every camp. Nobody cared where the parcels came from. The notes inside were in several languages: Yugoslav, French, English, Polish – a lot more. We’ll never forget the Red Cross or the St John. And you’ll see, now that the Yanks are in, they’ll come to Britain and they’ll fight with us in Europe.’

Cleo was deeply moved. ‘I’ve been a bit sheltered, Sam, I’m afraid. I didn’t know any of that about the Red Cross parcels. Good people everywhere. Makes me proud to have joined up.’

‘We’ve got a friend in the Land Army, Cleo,’ put in George. ‘She’s Sam’s sweetheart, isn’t she, Sam?’

Sam stood up and looked at his mother. ‘Isn’t it time for little boys to go to bed, Mum?’

‘I was just saying about Grace so you could tell Cleo about farm food,’ said the aggrieved George.

‘Well, actually—’ began Cleo, but before she could say another word they heard the doorbell.

‘I’ll get it, Mum,’ called Rose, already running quickly down the wooden stairs to the back door.

‘Sally Brewer, I don’t believe it.’ Rose’s excited voice rang out on the staircase. ‘Mum, Sam, George, you’ll never guess who’s here.’

George jumped up. ‘Sally’s a film star,’ he boasted somewhat erroneously, going to meet her. He stopped before running down the stairs and called back, ‘A real one.’

It was a lovely reunion: Rose, Sally and Sam actually there in the familiar, comfortable living room, with Grace and Daisy present in spirit. Phil was at sea. The family was conscious, as always, that since Ron had been killed it could never be complete again, but they did not burden others with their personal sorrows. They welcomed Sally, who had come down from London, where she had had the smallest of small parts in an actual West End play. Her news, which she had hoped would excite Rose, was that she was going to be in a musical – in Guildford.

Rose, and Cleo, who was almost as star-struck as George, groaned. ‘We’ve finished training. We’re leaving Guildford.’

They cheered up when Sally told them all manner of stories connected with her time in the theatre, actors and actresses she had met, screen tests she had had for film-makers and the, admittedly, tiny parts she had had in propaganda films. ‘I actually stood beside Noël Coward for three whole minutes in a film.’

‘The real Noël Coward. Wow.’ Cleo breathed out the word in awe.

Sally added Cleo to her list of ‘suitable friends to be invited’, and then organised the group into writing round-robin letters to Daisy, Grace and Phil. ‘Everyone writes a sentence about anything and signs it, and we’ll keep going till everyone has written at least one sentence on each letter.’

‘But I don’t know them, Sally,’ Cleo pointed out.

‘They won’t mind, and besides, you’re bound to meet them one day. Seems to me the whole world wants to be looked after by the Petries, and Flora and Fred want to look after everyone. Relax and enjoy!’

Much later than ten o’clock George, grudgingly, went off to bed, as did Flora, and Sam walked Sally back to her home.

‘We always thought Sam was sweet on Sally,’ Rose told Cleo as they brushed their hair before turning off the very dim bedroom light. ‘But you couldn’t doubt where his heart really is when you see him with Grace. Funny old thing, love.’

‘Hysterical,’ agreed Cleo.

They were asleep in minutes.

The great day came. The intensive study and hard work of just three weeks – which somehow seemed to have been much longer – were behind them.

With the exception of Chrissy, the occupants of Rose’s hut were wide awake by five-thirty; few of them had been able to sleep at all.

Would anyone be told that she just did not measure up? They had been together for such a short time but they were a team, a family, supporting one another, and today they would be parted and perhaps would never see each other again. It was a sobering thought for all but the two ‘boarding school girls’, who were quite used to meeting and parting.

‘Royal Mail, girls, fabulous invention, and there is the telephone,’ said Cleo. ‘Let’s make a pact to meet somewhere every year. All suggestions for suitable venues gladly received.’

‘Officer material if ever I saw it,’ said Avril Hunter. ‘Were you head girl, by any chance, Cleo?’

‘God, no,’ said Cleo, adjusting her beautifully tailored skirt. ‘For some obscure reason I did become a prefect and possibly became the teeniest bit bossy; it was that lovely magenta stripe on my grey blazer – went to my head, it did.’ She waited till the laughter died down before continuing, ‘Rose is definitely head girl material: popular, bright, attractive, and, to top it all, she’s an athlete. Bet they make her an officer.’

‘All my brains are in my legs,’ said Rose, blushing furiously. She was moved to hear that she was popular – Daisy was always the instantly popular twin. She really did not want to be selected for officer training. She could hear Stan’s voice – Stan who had not answered what she thought of as her ‘apologetic little letter’. ‘Not in your league, Rose.’ Despite her churning stomach, she pulled herself together. Whatever happened today was the beginning of something, and if army recruits worked half as hard as ATS recruits, he probably had no time for writing letters.

Everyone in the new intake confessed to a churning tummy. Would a girl be selected for cooking, cleaning, waiting tables in mess halls, as a storekeeper or a telephonist? Would the two university students be asked to train as translators – both had studied at least one foreign language – or might something even more secret and necessary be their lot? Who might become a lorry driver, a motorbike messenger, a mechanic or perhaps even an engineer or electrician? And those were not the only jobs available. With the necessary skills, a woman might be trained in wireless telegraphy, to use the newly developed radar systems. Yes, the opportunities were there.

The early morning hours seemed to crawl by. Would it ever be ten o’clock? But, of course, ten o’clock came, as usual.

By lunchtime, with many of them in a state almost of euphoria, they trooped into the canteen. Chrissy could scarcely contain herself and had tried to avoid lunch so that she could sit down and write to her son. ‘Can you imagine, girls?’ she asked them several times. ‘They don’t want me to clean. They think I’m secretarial material. What will my lad say when I tell him his mum’s going to be a secretary?’

No one was unkind enough to tell her that, since she could not type and knew nothing about shorthand, she had a long way to go.

‘You’ll get there, Chrissy, and secretaries make lots more money than cleaners. That cottage with roses round the door is just a matter of time.’

No one from Rose’s group had been selected for officer training.

Cleo had been selected for driver training. At the most, she could drive and, thanks to Rose, she now knew where to put petrol; Phyllis had been chosen for reasons even she could not begin to understand to join an anti-aircraft crew, looking out for enemy aircraft with the help of radar and searchlights.

‘Please don’t do any firing until you can recognise every type of plane in existence,’ Rose warned her, half seriously. ‘Don’t want you shooting down my sister.’

‘Only men fire guns.’

‘That doesn’t fill me with confidence,’ retorted Rose, and again everyone laughed.

Next they turned on Rose. ‘Come on, Rose, why so quiet and modest? What job have they given you? Chauffeur to the American general?’

Rose smiled and tried gamely to hide her bitter disappointment as she said, ‘No, very sensibly they’ve put me down as a mechanic – trainee, that is; it’s usually a man’s job. What’s your betting they still give me a woman’s wages?’

Each of the young women had been told that her wages would be two-thirds of that earned by the men. For Chrissy, it was still better than she had earned as a cleaner, and was, in her eyes, a definite step up.

Cleo hugged Rose. ‘I’m so sorry, Rose. They should have made you a driver. Probably there’s been a mistake. They’ll discover that and change your posting.’

‘I’ll be a good mechanic, Cleo. Honestly, I’m delighted; I was always afraid they’d throw me out altogether. Pity we won’t be together, though. It’s been fun.’

Promising to keep in touch, they continued to walk back towards their hut, where already packing-up was going on.

Cleo stopped. ‘I’m going to make a bet that by this time next year you’ll be a driver.’

Rose tried to smile. ‘For Mr Churchill, naturally.’

‘Of course. Just wait and see.’

Two days later, the newly ‘embodied’ auxiliaries boarded a bus heading for the station, the first step to their new posts where each one would have the rank of private. Cleo, in the window seat, noticed as the bus drove out that there was some unusual activity at the toilet block.

‘Goodness me. Don’t look, Rose; it’ll just upset you.’

Naturally Rose had to look. She sighed. ‘Let’s be charitable and say we’re glad for the next lot of trainees.’

The girls turned their heads again, looking towards the exciting future. Behind them auxiliary staff were – after many requests – hanging curtains on the fronts of the toilet cubicles.

FOUR (#u77d79044-eb05-512a-a8bd-13e98873a06b)

Preston, Lancashire, July 1942

It could have been worse. She might have been sent to Scotland. Not, thought Rose, that there was anything wrong with Scotland, but it was just so very far away from Dartford.

Preston was not too far really, and what she had seen from the train looked almost familiar. They were not stationed in the town itself but a few miles out. There was a river, the Ribble. Rose liked the sound of water flowing, jumping over stones on its way to the sea. She thought it would be pleasant to walk, run or cycle in the area around the base. It was mainly moorland and there was a high point called a fell not too far away. It was called Beacon Fell, possibly because beacons were lit on it on special days or to warn nearby inhabitants that trouble was coming.

She wondered if the beacon would be lit to warn of an air raid, then scolded herself for being silly. If she ever got time off she could get a train from Preston to London, and then another from London to Dartford. Cleo was in a place called Arundel. She’d have to look that up, but niggles in her brain hinted that Arundel was a lot closer to Dartford than it was to Preston. A really bright spot, however, was that Chrissy was here with her. To arrive at a new base and know not one person there would have been awful.

‘Pity we’re not in the same billet, Rose, but for me it’s lovely to know at least one person.’

They were sitting in the canteen enjoying their dinner of corned beef, potatoes and carrots – at least Rose was. Chrissy was merely pushing her carrots around.

‘I’m delighted you’re here too,’ said Rose, ‘but you don’t look too happy, Chrissy. I’ll fetch us a nice cup of tea and you can tell me what’s bothering you…if you want to, that is.’

She walked across to the tea trolley and poured two cups of tea. ‘Good heavens,’ she said aloud. ‘It’s too weak to run out of the pot.’

‘Very funny, Petrie. We’re lucky to be getting any tea at all. Kitchen does its best, but with rationing—’

‘Rationing? When was tea rationed?’

‘You been in outer space, girl?’ asked the irate cook. ‘At least two years.’

‘Since 1940? I was working in a munitions factory in ’40, but my parents sell tea, high-end market as well as the housewife’s choice, and I don’t remember a word about it.’

‘Parents don’t tell their offspring everything.’

Rose thanked the cook, apologised for complaining and then walked back to her table, remembering recent conversations about parents and the sacrifices they were prepared to make for their children.

‘Here you go, Chrissy, can’t exactly stand a spoon up in it, but it’s hot, wet and sweet enough!’

‘Just the way I like it,’ said Chrissy with an attempt at a smile.

Rose sat down beside her. ‘What is it? You can tell me and I’ll help if I can.’

Chrissy looked at Rose for a long moment. ‘It’s my Alan,’ she said at last, ‘my son. I haven’t had a word from him in weeks and I’m worried sick.’

‘Where is he?’

‘That’s it. I don’t know. He said in his last letter as he might be going overseas. Really excited, he was, and I pretended I were, an’ all. See the world: Paris, France, the mysterious East.’

‘Letters from overseas take much longer than from – where was he stationed?’

‘Aldershot.’

‘That must have been nice, not an awful long way from Guildford. Did he write to you in Guildford?’

‘Yes, but he won’t know this address if he didn’t get my letter telling him.’

‘That won’t matter, Chrissy. If he sends a letter to Guildford it’ll be sent on to you. Happens every day of the week, but try not to worry.’

Rose knew all about worrying over absent loved ones. They had waited for letters from Ron, and Flora would always treasure the few he had written before his death in action. Rose could not speak of her brother’s death to anyone, and especially not to a woman who was worried about her only son.

‘My brother Phil’s at sea, Chrissy. Sometimes it’s months between letters and then five or six arrive at the same time. He numbers them now and so Mum knows if one’s missing. Sometimes they do get lost and sometimes the lost one turns up months later. And when my brother Sam was on active service, Mum got letters every week and then it was months between…It doesn’t mean he’s not writing, Chrissy, just that there’s a hold-up somewhere. You have to stay positive.’

‘I’m sorry to be such a nuisance, Rose. I’m trying to concentrate on the typing and the shorthand but then I start worrying about Alan and I can’t see the keys or the symbols – all I can see is Alan’s face.’