Berlin Game

Len Deighton

Long-awaited reissue of the first part of the classic spy trilogy, GAME, SET and MATCH, when the Berlin Wall divided not just a city but a world.East is East and West is West - and they meet in Berlin…He was the best source the Department ever had, but now he desperately wanted to come over the Wall. ‘Brahms Four’ was certain a high-ranking mole was set to betray him. There was only one Englishman he trusted any more: someone from the old days.So they decided to put Bernard Samson back into the field after five sedentary years of flying a desk.The field is Berlin.The game is as baffling, treacherous and lethal as ever…

Cover designer’s note (#uf00f2f55-dd1c-5ede-8559-66e00437e784)

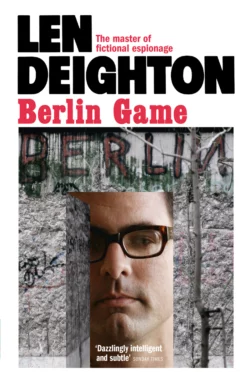

In November 1989, my wife Isolde and I had the pleasure of being in the German capital at the fall of the Berlin Wall, where I photographed many images of young and old citizens chipping away at the Wall. Along with these I photographed a number of versions of ‘Berlin’ that had been spray-painted on the wall’s surface, as well as the signboard at ‘Checkpoint Charlie’.

There can have been no more potent symbol of division, or barrier, than the Berlin Wall and it would always be a perfect visual representation of the city of Berlin, where so much of this story takes place.

As Len Deighton’s protagonist, Bernard Samson, penetrates beyond the Wall into the Eastern sector I thought I would cut a door into the Wall to symbolize his furtive activities.

At the heart of every one of the nine books in this triple trilogy is Bernard Samson, so I wanted to come up with a neat way of visually linking them all. When the reader has collected all nine books and displays them together in sequential order, the books’ spines will spell out Samson’s name in the form of a blackmail note made up of airline baggage tags. The tags were drawn from my personal collection, and are colourful testimony to thousands of air miles spent travelling the world.

Arnold Schwartzman OBE RDI

LEN DEIGHTON

Berlin Game

Copyright (#ulink_a10af23c-4ede-5485-ac70-5eee3817bfb7)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Hutchinson & Co. (Publishers) Ltd 1983

Copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 1983

Introduction copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 2010

Cover designer’s note © Arnold Schwartzman 2010

Cover design and photography © Arnold Schwartzman 2010

Len Deighton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008124984

Ebook Edition © March 2015 ISBN: 9780007387182

Version: 2018-05-08

Contents

Cover (#uc83a2387-e544-5275-afed-b8a73592039d)

Cover Designer’s Note (#uabfdfe30-3632-5d69-b8af-34a52b28783b)

Title Page (#u21a61abb-1eb2-5bbe-ad0a-2f22a69071ff)

Copyright (#u6e3342bd-0d58-5e31-b6a2-d3891207ea51)

Introduction (#u7f54af06-ae31-516c-9e25-9e770a4f061c)

Chapter 1 (#uf7ae034b-22a8-55ed-9f7a-3aff82874f41)

Chapter 2 (#u6b7507a0-6eab-5089-9416-d8210c906d23)

Chapter 3 (#u300c536a-d779-5e70-abef-55ea9c611f99)

Chapter 4 (#u018724c6-aefb-5a00-b2b8-4a8df4cbe5ac)

Chapter 5 (#u107314ab-141b-5ba3-b07b-3b1fc86c6c7c)

Chapter 6 (#u0758aa5d-f3f3-5900-a383-e679ad890109)

Chapter 7 (#u4be4b180-15b4-5579-bbc3-dde3d43e2dbc)

Chapter 8 (#u43f7299e-6a99-5c48-b91f-9fb886ead1a2)

Chapter 9 (#u75d5a190-b1c1-5f69-a3d0-72e207390a3d)

Chapter 10 (#u0d8a80f6-4234-56a4-9b4a-a16d4c1d35df)

Chapter 11 (#u3d6cb6da-2138-5e4c-a0df-8c0cd5d82b50)

Chapter 12 (#ud6e5ab4f-8faf-561c-8ebe-06c3f0740f2d)

Chapter 13 (#u5cc44b40-b68b-5f19-8289-f214f70bfabe)

Chapter 14 (#u05a82a78-24fb-52d0-b7f8-7089dc2035c9)

Chapter 15 (#u029b53f8-44fd-5c51-a398-806b73692337)

Chapter 16 (#ua05ea923-6ffd-5a74-9658-b87580bc33ec)

Chapter 17 (#u1f1b2aec-cce2-5b6a-a994-e19c96de4379)

Chapter 18 (#ub387745c-c7b8-595d-87dd-bad5d4b46f26)

Chapter 19 (#u82c556eb-3bc5-5db8-9bb4-2719dfc97ccc)

Chapter 20 (#ub06801b5-c244-5e57-abfc-c901fe549f81)

Chapter 21 (#udb18c64f-e055-5aac-b90f-818fb67a7d17)

Chapter 22 (#uda51d4e5-cda1-55b2-84ad-b85b8605acf8)

Chapter 23 (#ub1afb346-9cdb-5042-bb54-8ff48d5bfad6)

Chapter 24 (#u4e409ea3-622a-5956-8939-7e3f05d9ae4b)

Chapter 25 (#u585bf764-776c-5251-b8ca-40c8b623a7c6)

Chapter 26 (#uc96d9518-7e89-5477-850c-2cb5dd62a253)

Chapter 27 (#u5e7d0675-2e66-5c84-a43a-3b98048cad4c)

Chapter 28 (#u8130964b-885c-577c-aff7-be9056de7ab9)

Further Reading (#u16a23daa-14b6-5596-8f82-1fa0e0e7fb05)

About the Author (#u78497484-699f-56a6-a379-5e94ffb68df8)

By Len Deighton (#u1a431056-7e3b-56cb-8eb9-281ee720b8b5)

About the Publisher (#u668fc31d-c065-5ba7-a684-5272e5ecc14a)

Introduction (#uf00f2f55-dd1c-5ede-8559-66e00437e784)

Writers are frequently advised to shape their stories along conventional lines. This means simplify the plot-line, eliminate descriptive passages, emphasize and extend action, minimize characterization and forget sub-plots. This sort of well-intentioned advice is apt to transform a book into a film script. Not a bad move, you say. That’s true, unless you wanted to write a book.

Coming to writing at a time when the formalities of such instruction were unavailable I was likely to break one or the other of these rules: sometimes all of them in one go. I suppose many writers are drawn to the problems of characterization. That certainly was my prime interest; not just the characterization of the central characters but of spear-carriers too. Until Berlin Game I had fretted and struggled as I tried to retain the pace of the action while expanding the reality of the people in the story. To give my characters a real, or at least a convincing, life demanded more space. Did giving them a domestic dimension mean pressing the pause button in order to relate the dull routines of mortgages, electric bills, children’s ailments and traffic jams? No, that is not the way to treat your readers unless you just don’t care about them; and in that case you should be writing literary novels.

I have always been a planner. I remain in awe of writers who complete a book in ten days as friends of mine do. And even more wide-eyed to hear others proclaim that they customarily don’t know how their stories will end until they are writing the final chapter. I am far too timid for that kind of perilous pursuit.

My writing life is littered with the notes of abandoned stories, and Berlin Game had been balanced on the lid of the litterbin for a long time. The basic idea attracted me very much but there were problems that I’d not been able to crack. It was while on the final stages of Goodbye Mickey Mouse, a story about American fighter pilots flying out of England during the war, that I went back to some ideas about the man I came to call Bernard Samson. Goodbye Mickey Mouse had been described as ‘a romantic war story’ and although that seemed a surprising verdict at the time, I could not deny its validity. It was intended to be a book about a father and his son but for many readers the son’s love affair with his English girlfriend dominated the book. The meetings of a variety of English characters with equally varied American airmen were just as important as the air battles. Yet, more than once, I regretted not being able to integrate the English characters with the battlefield conditions at the airbase. Why hadn’t I cast the girlfriend as a nurse, or as a radio operator with an ear to the men fighting and dying? Well that was another sort of book, and it was just as well I didn’t write it because it was not the sort of book I wanted to read and that’s always a deciding factor.

But out of these ponderings came the idea that one could have a story in which wives and girlfriends were shoulder to shoulder with the fighting men. What about superior to them and in authority over them? And why not a spy story? I had a head filled with real-life espionage stories and Berlin was like a second home for me. I had good contacts on both sides of the Wall and my wonderful wife spoke German like a native. Now the domestic dimension would not be so domestic. Pillow talk would concern matters of life and death. Fidelity would not just be to the marriage vows but to the Official Secrets Act too. I scribbled these notes on the blank side of a US Air Force document that confirmed that I was physically fit enough to fly back-seat in a Phantom jet fighter. This was the beginning of Berlin Game.

I became so invigorated at the format I was drafting that I dismissed the idea of confining it to one book. What about a trilogy? Wait! What about two trilogies? Why not make a wall chart and see what it all looked like? That is what I did. This must not be a continuing series; all the books must be standalone stories, with no dependence on anything that had gone before or anything that might come afterwards. Impossible? No, just hard work.

Speaking as a reader of books rather than as a writer, I have always measured a book’s success by the way in which the characters were affected by events as the story progressed. This ‘development’, the way that experience changes the people in the story, is an important repayment to the reader for the time and effort he or she has given to you and your book. Change is not to be measured in elapsed time. For the Berlin family depicted in Winter almost half a century passed before the final page was completed. In Bomber, the airmen, and the German civilians under attack from the air, changed just as radically in little more than 24 hours.

So the prospect of planning and writing many books using the same characters (each of them aging and changing) was both attractive and daunting. They would grow older; perhaps wiser, or perhaps more foolish, or bitter. They would suffer setbacks and ailments; delight, sudden death and despair. And in fiction, as in real life, there was no going back. An inconvenient death in book number three was not something I could rectify in book number four. For all those reasons the writing of Berlin Game, the first book, required more preparatory work than any of the subsequent ones. Here were the people – the foundation – upon which the Bernard Samson stories would be built and balanced. Vague characterizations might have provided a way of keeping the options open. Better to start off with strongly realized people who would clash and caper according to rapidly changing events. Anyone who spent much time in Berlin’s eastern sector – and the Zone too – could not fail to see that Germany’s communist regime was shaky, although shaky regimes repressive enough sometimes continue for a long time. I certainly had no dates in mind but, as I have depicted in the books, there was a weakening of resolve and the regime was becoming more impoverished every day. Fundamentally agricultural, with no exports worth consideration, and a middle class with no income worth taxing, the DDR was a living corpse. I had previously written of the likelihood of the two Germanys becoming a Federation. The bureaucrats of both regimes were comparing pension plans and the border guards were shooting fewer escapers, which had to be a good sign. While people in the West were talking about, and even admiring the stability of the so-called German Democratic Republic, its rotten fabric was there for anyone who wasn’t wearing pink-coloured glasses. I was further convinced of all this when mingling with the drunks on Ascension Day and this is an experience that inspired the final chapters of Berlin Game. Collapse was sure to come eventually but little did I guess that the Wall would come down with such a spectacular crash. Telling the story of this amazing period was an opportunity that could not be ignored.

You can see what a wonderful life I have enjoyed. Melvyn Bragg once interviewed me and told the TV audience that I was the hardest working writer he had ever met. I was delighted; but he was wrong; I have never worked at all. Wrestling with the problems of writing books was like a holiday and the people I mixed with were a constant delight. ‘There are no villains in Deighton books,’ said one reviewer and other critics echoed this verdict. It was true. Finding somewhere, some redeeming feature of those we don’t much like, is a moral duty and a satisfying task.

Len Deighton, 2010

1 (#uf00f2f55-dd1c-5ede-8559-66e00437e784)

‘How long have we been sitting here?’ I said. I picked up the field glasses and studied the bored young American soldier in his glass-sided box.

‘Nearly a quarter of a century,’ said Werner Volkmann. His arms were resting on the steering wheel and his head was slumped on them. ‘That GI wasn’t even born when we first sat here waiting for the dogs to bark.’

Barking dogs, in their compound behind the remains of the Hotel Adlon, were usually the first sign of something happening on the other side. The dogs sensed any unusual happenings long before the handlers came to get them. That’s why we kept the window open; that’s why we were frozen nearly to death.

‘That American soldier wasn’t born, the spy thriller he’s reading wasn’t written, and we both thought the Wall would be demolished within a few days. We were stupid kids but it was better then, wasn’t it, Bernie?’

‘It’s always better when you’re young, Werner,’ I said.

This side of Checkpoint Charlie had not changed. There never was much there; just one small hut and some signs warning you about leaving the Western Sector. But the East German side had grown far more elaborate. Walls and fences, gates and barriers, endless white lines to mark out the traffic lanes. Most recently they’d built a huge walled compound where the tourist buses were searched and tapped, and scrutinized by gloomy men who pushed wheeled mirrors under every vehicle lest one of their fellow-countrymen was clinging there.

The checkpoint is never silent. The great concentration of lights that illuminate the East German side produces a steady hum like a field of insects on a hot summer’s day. Werner raised his head from his arms and shifted his weight. We both had sponge-rubber cushions under us; that was one thing we’d learned in a quarter of a century. That and taping the door switch so that the interior light didn’t come on every time the car door opened. ‘I wish I knew how long Zena will stay in Munich,’ said Werner.

‘Can’t stand Munich,’ I told him. ‘Can’t stand those bloody Bavarians, to tell you the truth.’

‘I was only there once,’ said Werner. ‘It was a rush job for the Americans. One of our people was badly beaten and the local cops were no help at all.’ Even Werner’s English was spoken with the strong Berlin accent that I’d known since we were at school. Now Werner Volkmann was forty years old, thickset, with black bushy hair, black moustache, and sleepy eyes that made it possible to mistake him for one of Berlin’s Turkish population. He wiped a spyhole of clear glass in the windscreen so that he could see into the glare of fluorescent lighting. Beyond the silhouette of Checkpoint Charlie, Friedrichstrasse in the East Sector shone as bright as day. ‘No,’ he said. ‘I don’t like Munich at all.’

The night before, Werner, after many drinks, had confided to me the story of his wife, Zena, running off with a man who drove a truck for the Coca-Cola company. For the previous three nights he’d provided me with a place on a lumpy sofa in his smart apartment in Dahlem, right on the edge of Grunewald. But sober, we kept up the pretence that his wife was visiting a relative. ‘There’s something coming now,’ I said.

Werner did not bother to move his head from where it rested on the seatback. ‘It’s a tan-coloured Ford. It will come through the checkpoint, park over there while the men inside have a coffee and hotdog, then they’ll go back in to the East Sector just after midnight.’

I watched. As he’d predicted, it was a tan-coloured Ford, a panel truck, unmarked, with West Berlin registration.

‘We’re in the place they usually park,’ said Werner. ‘They’re Turks who have girlfriends in the East. The regulations say you have to be out before midnight. They go back there again after midnight.’

‘They must be some girls!’ I said.

‘A handful of Westmarks goes a long way over there,’ said Werner. ‘You know that, Bernie.’ A police car with two cops in it cruised past very slowly. They recognized Werner’s Audi and one of the cops raised a hand in a weary salutation. After the police car moved away, I used my field glasses to see right through the barrier to where an East German border guard was stamping his feet to restore circulation. It was bitterly cold.

Werner said, ‘Are you sure he’ll cross here, rather than at the Bornholmerstrasse or Prinzenstrasse checkpoints?’

‘You’ve asked me that four times, Werner.’

‘Remember when we first started working for intelligence. Your dad was in charge then – things were very different. Remember Mr Gaunt – the fat man who could sing all those funny Berlin cabaret songs – betting me fifty marks it would never go up … the Wall, I mean. He must be getting old now. I was only eighteen or nineteen, and fifty marks was a lot of money in those days.’

‘Silas Gaunt, that was. He’d been reading too many of those “guidance reports” from London,’ I said. ‘For a time he convinced me you were wrong about everything, including the Wall.’

‘But you didn’t make any bets,’ said Werner. He poured some black coffee from his Thermos into a paper cup and passed it to me.

‘But I volunteered to go over there that night they closed the sector boundaries. I was no brighter than old Silas. It was just that I didn’t have fifty marks to spare for betting.’

‘The cabdrivers were the first to know. About two o’clock in the morning, the radio cabs were complaining about the way they were being stopped and questioned each time they crossed. The dispatcher in the downtown taxi office told his drivers not to take anyone else across to the East Sector, and then he phoned me to tell me about it.’

‘And you stopped me from going,’ I said.

‘Your dad told me not to take you.’

‘But you went over there, Werner. And old Silas went with you.’ So my father had prevented my going over there the night they sealed the sector. I didn’t know until now.

‘We went across about four-thirty that morning. There were Russian trucks, and lots of soldiers dumping rolls of barbed wire outside the Charité Hospital. We came back quite soon. Silas said the Americans would send in tanks and tear the wire down. Your dad said the same thing, didn’t he?’

‘The people in Washington were too bloody frightened, Werner. The stupid bastards at the top thought the Russkies were going to move this way and take over the Western Sector of the city. They were relieved to see a wall going up.’

‘Maybe they know things we don’t know,’ said Werner.

‘You’re right,’ I said. ‘They know that the service is run by idiots. But the word is leaking out.’

Werner permitted himself a slight smile. ‘And then, about six in the morning, you heard the sound of the heavy trucks and construction cranes. Remember going on the back of my motorcycle to see them stringing the barbed wire across Potsdamerplatz? I knew it would happen eventually. It was the easiest fifty marks I ever earned. I can’t think why Mr Gaunt took my bet.’

‘He was new to Berlin,’ I said. ‘He’d just finished a year at Oxford, lecturing on political science and all that statistical bullshit the new kids start handing out the moment they arrive.’

‘Maybe you should go and lecture there,’ said Werner with just a trace of sarcasm. ‘You didn’t go to university did you, Bernie?’ It was a rhetorical question. ‘Neither did I. But you’ve done well without it.’ I didn’t answer, but Werner was in the mood to talk now. ‘Do you ever see Mr Gaunt? What beautiful German he spoke. Not like yours and mine – Hochdeutsch, beautiful.’

Werner, who seemed to be doing better than I was, with his export loan business, looked at me expecting a reply. ‘I married his niece,’ I said.

‘I forgot that old Silas Gaunt was related to Fiona. I hear she is very important in the Department nowadays.’

‘She’s done well,’ I said. ‘But she works too hard. We don’t have enough time together with the kids.’

‘You must be making a pot of money,’ said Werner. ‘Two of you senior staff, with you on field allowances … But Fiona has money of her own, doesn’t she? Isn’t her father some kind of tycoon? Couldn’t he find a nice soft job for you in his office? Better than sitting out here freezing to death in a Berlin side street.’

‘He’s not going to come,’ I said after watching the barrier descend again and the border guard go back into his hut. The windscreen had misted over again so that the lights of the checkpoint became a fairyland of bright blobs.

Werner didn’t answer. I had not confided to him anything about what we were doing in his car at Checkpoint Charlie, with a tape recorder wired into the car battery and a mike taped behind the sun visor and a borrowed revolver making an uncomfortable bulge under my arm. After a few minutes he reached forward and wiped a clear spot again. ‘The office doesn’t know you’re using me,’ he said.

He was hoping like hell I’d say Berlin Station had forgiven him for his past failings. ‘They wouldn’t mind too much,’ I lied.

‘They have a long memory,’ complained Werner.

‘Give them time,’ I said. The truth was that Werner was on the computer as ‘non-critical employment only’, a classification that prevented anyone employing him at all. In this job everything was ‘critical’.

‘They didn’t okay me, then?’ Werner said, suddenly guessing at the truth: that I’d come into town without even telling Berlin Station that I’d arrived.

‘What do you care?’ I said. ‘You’re making good money, aren’t you?’

‘I could be useful to them, and the Department could help me more. I told you all that.’

‘I’ll talk to the people in London,’ I said. ‘I’ll see what I can do.’

Werner was unmoved by my promise. ‘They’ll just refer it to the Berlin office, and you know what the answer will be.’

‘Your wife,’ I said. ‘Is she a Berliner?’

‘She’s only twenty-two,’ said Werner wistfully. ‘The family was from East Prussia …’ He reached inside his coat as if searching for cigarettes, but he knew I wouldn’t permit it – cigarettes and lighters are too damned conspicuous after dark – and he closed his coat again. ‘You probably saw her photo on the sideboard – a small, very pretty girl with long black hair.’

‘So that’s her,’ I said, although in fact I’d not noticed the photo. At least I’d changed the subject. I didn’t want Werner quizzing me about the office. He should have known better than that.

Poor Werner. Why does the betrayed husband always cut such a ridiculous figure? Why isn’t the unfaithful partner the comical one? It was all so unfair; no wonder Werner pretended his wife was visiting relatives. He was staring ahead, his big black eyebrows lowered as he concentrated on the checkpoint. ‘I hope he wasn’t trying to come through with forged papers. They put everything under the ultraviolet lights nowadays, and they change the markings every week. Even the Americans have given up using forged papers – it’s suicide.’

‘I don’t know anything about that,’ I told him. ‘My job is just to pick him up and debrief him before the office sends him to wherever he has to go.’

Werner turned his head; the bushy black hair and dark skin made his white teeth flash like a toothpaste commercial. ‘London wouldn’t send you over here for that kind of circus, Bernie. For that kind of task they send office boys, people like me.’

‘We’ll go and get something to eat and drink, Werner,’ I said. ‘Do you know some quiet restaurant where they have sausage and potatoes and good Berlin beer?’

‘I know just the place, Bernie. Straight up Friedrichstrasse, under the railway bridge at the S-Bahn station and it’s on the left. On the bank of the Spree: Weinrestaurant Ganymed.’

‘Very funny,’ I said. Between us and the Ganymed there was a wall, machine guns, barbed wire, and two battalions of gun-toting bureaucrats. ‘Turn this jalopy round and let’s get out of here.’

He switched on the ignition and started up. ‘I’m happier with her away,’ he said. ‘Who wants to have a woman waiting at home to ask you where you’ve been and why you’re back so late?’

‘You’re right, Werner,’ I said.

‘She’s too young for me. I should never have married her.’ He waited a moment while the heater cleared the glass a little. ‘Try again tomorrow, then?’

‘No further contact, Werner. This was the last try for him. I’m going back to London tomorrow. I’ll be sleeping in my own bed.’

‘Your wife … Fiona. She was nice to me that time when I had to work inside for a couple of months.’

‘I remember that,’ I said. Werner had been thrown out of a window by two East German agents he’d discovered in his apartment. His leg was broken in three places and it took ages for him to recover fully.

‘And you tell Mr Gaunt I remember him. He’s long ago retired, I know, but I suppose you still see him from time to time. You tell him any time he wants another bet on what the Ivans are up to, he calls me up first.’

‘I’ll see him next weekend,’ I said. ‘I’ll tell him that.’

2 (#uf00f2f55-dd1c-5ede-8559-66e00437e784)

‘I thought you must have missed the plane,’ said my wife as she switched on the bedside light. She’d not yet got to sleep; her long hair was hardly disarranged and the frilly nightdress was not rumpled. She’d gone to bed early by the look of it. There was a lighted cigarette on the ashtray. She must have been lying there in the dark, smoking and thinking about her work. On the side table there were thick volumes from the office library and a thin blue Report from the Select Committee on Science and Technology, with notebook and pencil and the necessary supply of Benson & Hedges cigarettes, a considerable number of which were now only butts packed tightly in the big cut-glass ashtray she’d brought from the sitting room. She lived a different sort of life when I was away; now it was like going into a different house and a different bedroom, to a different woman.

‘Some bloody strike at the airport,’ I explained. There was a tumbler containing whisky balanced on the clock-radio. I sipped it; the ice cubes had long since melted to make a warm weak mixture. It was typical of her to prepare a treat so carefully – with linen napkin, stirrer and some cheese straws – and then forget about it.

‘London Airport?’ She noticed her half-smoked cigarette and stubbed it out and waved away the smoke.

‘Where else do they go on strike every day?’ I said irritably.

‘There was nothing about it on the news.’

‘Strikes are not news any more,’ I said. She obviously thought that I had not come directly from the airport, and her failure to commiserate with me over three wasted hours there did not improve my bad temper.

‘Did it go all right?’

‘Werner sends his best wishes. He told me that story about your Uncle Silas betting him fifty marks about the building of the Wall.’

‘Not again,’ said Fiona. ‘Is he ever going to forget that bloody bet?’

‘He likes you,’ I said. ‘He sent his best wishes.’ It wasn’t exactly true, but I wanted her to like him as I did. ‘And his wife has left him.’

‘Poor Werner,’ she said. Fiona was very beautiful, especially when she smiled that sort of smile that women save for men who have lost their woman. ‘Did she go off with another man?’

‘No,’ I said untruthfully. ‘She couldn’t stand Werner’s endless affairs with other women.’

‘Werner!’ said my wife, and laughed. She didn’t believe that Werner had affairs with lots of other women. I wondered how she could guess so correctly. Werner seemed an attractive sort of guy to my masculine eyes. I suppose I will never understand women. The trouble is that they understand me; they understand me too damned well. I took off my coat and put it on a hanger. ‘Don’t put your overcoat in the wardrobe,’ said Fiona. ‘It needs cleaning. I’ll take it in tomorrow.’ As casually as she could, she added, ‘I tried to get you at the Steigerberger Hotel. Then I tried the duty officer at Olympia but no one knew where you were. Billy’s throat was swollen. I thought it might be mumps.’

‘I wasn’t there,’ I said.

‘You asked the office to book you there. You said it’s the best hotel in Berlin. You said I could leave a message there.’

‘I stayed with Werner. He’s got a spare room now that his wife’s gone.’

‘And shared all those women of his?’ said Fiona. She laughed again. ‘Is it all part of a plan to make me jealous?’

I leaned over and kissed her. ‘I’ve missed you, darling. I really have. Is Billy okay?’

‘Billy’s fine. But that damned man at the garage gave me a bill for sixty pounds!’

‘For what?’

‘He’s written it all down. I told him you’d see about it.’

‘But he let you have the car?’

‘I had to collect Billy from school. He knew that before he did the service on it. So I shouted at him and he let me take it.’

‘You’re a wonderful wife,’ I said. I undressed and went into the bathroom to wash and to brush my teeth.

‘And it went well?’ she called.

I looked at myself in the long mirror. It was just as well that I was tall, for I was getting fatter, and that Berlin beer hadn’t helped matters. ‘I did what I was told,’ I said, and finished brushing my teeth.

‘Not you, darling,’ said Fiona. I switched on the Water-Pik and above its chugging sound I heard her add, ‘You never do what you are told, you know that.’

I went back into the bedroom. She’d combed her hair and smoothed the sheet on my side of the bed. She’d put my pyjamas on the pillow. They consisted of a plain red jacket and paisley-printed trousers. ‘Are these mine?’

‘The laundry didn’t come back this week. I phoned them. The driver is ill … so what can you say?’

‘I didn’t check into the Berlin office at all, if that’s what’s eating you,’ I admitted. ‘They’re all young kids in there, don’t know their arse from a hole in the ground. I feel safer with one of the old-timers like Werner.’

‘Suppose something happened? Suppose there was trouble and the duty officer didn’t even know you were in Berlin? Can’t you see how silly it is not to give them some sort of perfunctory call?’

‘I don’t know any of those Olympia Stadion people any more, darling. It’s all changed since Frank Harrington took over. They are youngsters, kids with no field experience and lots and lots of theories from the training school.’

‘But your man turned up?’

‘No.’

‘You spent three days there for nothing?’

‘I suppose I did.’

‘They’ll send you in to get him. You realize that, don’t you?’

I got into bed. ‘Nonsense. They’ll use one of the West Berlin people.’

‘It’s the oldest trick in the book, darling. They send you over there to wait … for all you know, he wasn’t even in contact. Now you’ll go back and report a failed contact and you’ll be the one they send in to get him. My God, Bernie, you are a fool at times.’

I hadn’t looked at it like that, but there was more than a grain of truth in Fiona’s cynical viewpoint. ‘Well, they can find someone else,’ I said angrily. ‘Let one of the local people go over to get him. My face is too well known there.’

‘They’ll say they’re all kids without experience, just what you yourself said.’

‘It’s Brahms Four,’ I told her.

‘Brahms – those network names sound so ridiculous. I liked it better when they had codewords like Trojan, Wellington and Claret.’

The way she said it was annoying. ‘The postwar network names are specially chosen to have no identifiable nationality,’ I said. ‘And the number four man in the Brahms network once saved my life. He’s the one who got me out of Weimar.’

‘He’s the one who is kept so damned secret. Yes, I know. Why do you think they sent you? And now do you see why they are going to make you go in and get him?’ Beside the bed, my photo stared back at me from its silver frame. Bernard Samson, a serious young man with baby face, wavy hair and horn-rimmed glasses looked nothing like the wrinkled old fool I shaved every morning.

‘I was in a spot. He could have kept going. He didn’t have to come back all the way to Weimar.’ I settled into my pillow. ‘How long ago was that – eighteen years, maybe twenty?’

‘Go to sleep,’ said Fiona. ‘I’ll phone the office in the morning and say you are not well. It will give you time to think.’

‘You should see the pile of work on my desk.’

‘I took Billy and Sally to the Greek restaurant for his birthday. The waiters sang happy birthday and cheered him when he blew the candles out. It was sweet of them. I wish you’d been there.’

‘I won’t go. I’ll tell the old man in the morning. I can’t do that kind of thing any more.’

‘And there was a phone call from Mr Moore at the bank. He wants to talk with you. He said there’s no hurry.’

‘And we both know what that means,’ I said. ‘It means phone me back immediately or else!’ I was close to her now and I could smell perfume. Had she put it on just for me, I wondered.

‘Harry Moore isn’t like that. At Christmas we were nearly seven hundred overdrawn, and when we saw him at my sister’s party he said not to worry.’

‘Brahms Four took me to the house of a man named Busch – Karl Busch – who had this empty room in Weimar …’ It was all coming back to me. ‘We stayed there three days and afterwards Karl Busch went back there. They took Busch up to the security barracks in Leipzig. He was never seen again.’

‘You’re senior staff now, darling,’ she said sleepily. ‘You don’t have to go anywhere you don’t want to.’

‘I phoned you last night,’ I said. ‘It was two o’clock in the morning but there was no reply.’

‘I was here, asleep,’ she said. She was awake and alert now. I could tell by the tone of her voice.

‘I let it ring for ages,’ I said. ‘I tried twice. Finally I got the operator to dial it.’

‘Then it must be the damned phone acting up again. I tried to phone here for Nanny yesterday afternoon and there was no reply. I’ll tell the engineers tomorrow.’

3 (#uf00f2f55-dd1c-5ede-8559-66e00437e784)

Richard Cruyer was the German Stations Controller, the man to whom I reported. He was younger than I was by two years and his apologies for this fact gave him opportunities for reminding himself of his fast promotion in a service that was not noted for its fast promotions.

Dicky Cruyer had curly hair and liked to wear open-neck shirts and faded jeans, and be the Wunderkind amongst all the dark suits and Eton ties. But under all the trendy jargon and casual airs, he was the most pompous stuffed shirt in the whole Department.

‘They think it’s a cushy number in here, Bernard,’ he said while stirring his coffee. ‘They don’t realize the way I have the Deputy Controller (Europe) breathing down my neck and endless meetings with every damned committee in the building.’

Even Cruyer’s complaints were contrived to show the world how important he was. But he smiled to let me know how well he endured his troubles. He had his coffee served in a fine Spode china cup and saucer, and he stirred it with a silver spoon. On the mahogany tray there was another Spode cup and saucer, a matching sugar bowl, and a silver creamer fashioned in the shape of a cow. It was a valuable antique – Dicky had told me that many times – and at night it was locked in the secure filing cabinet, together with the log and the current carbons of the mail. ‘They think it’s all lunches at the Mirabelle and a fine with the boss.’

Dicky always said fine rather than brandy or cognac. Fiona told me he’d been saying it ever since he was president of the Oxford University Food and Wine Society as an undergraduate. Dicky’s image as a gourmet was not easy to reconcile with his figure, for he was a thin man, with thin arms, thin legs and thin bony hands and fingers, with one of which he continually touched his thin bloodless lips. It was a nervous gesture, provoked, said some people, by the hostility around him. This was nonsense of course, but I did dislike the little creep, I will admit that.

He sipped his coffee and then tasted it carefully, moving his lips while staring at me as if I might have come to sell him the year’s crop. ‘It’s just a shade bitter, don’t you think, Bernard?’

‘Nescafé all tastes the same to me,’ I said.

‘This is pure chagga, ground just before it was brewed.’ He said it calmly but nodded to acknowledge my little attempt to annoy him.

‘Well, he didn’t turn up,’ I said. ‘We can sit here drinking chagga all morning and it won’t bring Brahms Four over the wire.’

Dicky said nothing.

‘Has he re-established contact yet?’ I asked.

Dicky put his coffee on the desk, while he riffled some papers in a file. ‘Yes. We received a routine report from him. He’s safe.’ Dicky chewed a fingernail.

‘Why didn’t he turn up?’

‘No details on that one.’ He smiled. He was handsome in the way that foreigners think bowler-hatted English stockbrokers are handsome. His face was hard and bony and the tan from his Christmas in the Bahamas had still not faded. ‘He’ll explain in his own good time. Don’t badger the field agents – that has always been my policy. Right, Bernard?’

‘It’s the only way, Dicky.’

‘Ye gods! How I’d love to get back into the field just once more! You people have the best of it.’

‘I’ve been off the field list for nearly five years, Dicky. I’m a desk man now, like you.’ Like you have always been is what I should have said, but I let it go. ‘Captain’ Cruyer he’d called himself when he returned from the Army. But he soon realized how ridiculous that title sounded to a Director-General who’d worn a General’s uniform. And he realized too that ‘Captain’ Cruyer would be an unlikely candidate for that illustrious post.

He stood up, smoothed his shirt, and then sipped coffee, holding his free hand under the cup to guard against drips. He noticed that I hadn’t drunk my chagga. ‘Would you prefer tea?’

‘Is it too early for a gin and tonic?’

He didn’t respond to this question. ‘I think you feel beholden to our friend Bee Four. You still feel grateful about his coming back to Weimar for you.’ He greeted my look of surprise with a knowing nod. ‘I read the files, Bernard. I know what’s what.’

‘It was a decent thing to do,’ I said.

‘It was,’ said Dicky. ‘It was a truly decent thing to do, but that wasn’t why he did it. Not only that.’

‘You weren’t there, Dicky.’

‘Bee Four panicked, Bernard. He fled. He was near the border, at some godforsaken little place in Thüringerwald, by the time our people intercepted him and told him he wasn’t wanted for questioning by the KGB – or anyone else, for that matter.’

‘It’s ancient history,’ I said.

‘We turned him round,’ said Cruyer. It had become ‘we’ I noticed. ‘We gave him some chickenfeed and told him to go back and play the outraged innocent. We told him to cooperate with them.’

‘Chickenfeed?’

‘Names of people who’d already escaped, safe houses long since abandoned … bits and pieces that would make Brahms Four look good to the KGB.’

‘But they got Busch, the man who was sheltering me.’

Unhurriedly, Cruyer finished his coffee and wiped his lips with a linen napkin from the tray. ‘We got two of you out. I’d say that’s not bad for that sort of crisis – two out of three. Busch went back to his house to get his stamp collection … Stamp collection! What can you do with a man like that? They put him in the bag of course.’

‘The stamp collection was probably his life savings,’ I said.

‘Perhaps it was, and that’s how they put him in the bag, Bernard. No second chances with those swine. I know that, you know that, and he knew it too.’

‘So that’s why our field people don’t like Brahms Four.’

‘Yes, that’s why they don’t like him.’

‘They think he informed on that Erfurt network.’

Cruyer shrugged. ‘What could we do? We could hardly spread the word that we’d invented that story to make the fellow persona grata with the KGB.’ Cruyer walked across to his drinks cabinet and poured some gin into a large Waterford glass tumbler.

‘Plenty of gin, not too much tonic,’ I said. Cruyer turned to stare blankly at me. ‘If that’s for me,’ I added. So there had been a blunder. They’d told Brahms Four to reveal old Busch’s address, then the poor old sod had gone back for his stamps. And run into the arms of a KGB arrest squad.

Dicky put a little more gin into the glass, and added ice cubes gently so that they would not splash. He brought it, together with a small bottle of tonic, which I left unused. ‘No need for you to concern yourself with this one any more, Bernard. You did your bit in going to Berlin. We’ll let one of the others take over now.’

‘Is he in trouble?’

Cruyer went back to the drinks cabinet and busied himself tidying away the bottle caps and stirrer. Then he closed the cabinet doors and said, ‘Do you know the sort of material Brahms Four has been supplying?’

‘Economics intelligence. He works for an East German bank.’

‘He is the most carefully protected source we have in Germany. You are one of the few people ever to have seen him face to face.’

‘And that was almost twenty years ago.’

‘He works through the mail – always local addresses to avoid the censors and the security – posting his material to various members of the Brahms net. In emergencies he uses a dead-letter drop. But that’s all – no microdots, no one-time pads, no codes, no micro transmitters, no secret ink. Very old-fashioned.’

‘And very safe,’ I said.

‘Very old-fashioned and very safe, so far,’ agreed Dicky. ‘Even I don’t have access to the Brahms Four file. No one knows anything about him except that he’s been getting material from somewhere at the top of the tree. All we can do is guess.’

‘And you’ve guessed,’ I prompted him, knowing that Dicky was going to tell me anyway.

‘From Bee Four we are getting important decisions of the Deutsche Investitions Bank. And from the Deutsche Bauern Bank. Those state banks provide long-term credit for industry and for agriculture. Both banks are controlled by the Deutsche Notenbank, through which come all remittances, payments and clearing for the whole country. Now and again we get good notice of what the Moscow Narodny Bank is doing and regular reports about the COMECON briefings. I think Brahms Four is a secretary or personal assistant to one of the directors of the Deutsche Notenbank.’

‘Or a director?’

‘All banks have an economics intelligence department. Being head of that department is not a job an ambitious banker craves for, so they get switched around. Brahms Four has been feeding us this sort of thing too long to be anything but a clerk or assistant.’

‘You’ll miss him. Too bad you have to pull him out,’ I said.

‘Pull him out? I’m not trying to pull him out. I want him to stay right where he is.’

‘I thought …’

‘It’s his idea that he should come over to the West, not mine! I want him to remain where he is. I can’t afford to lose him.’

‘Is he getting frightened?’

‘They all get frightened eventually,’ said Cruyer. ‘It’s battle fatigue. The strain of it all gets them down. They get older and they get tired and they start looking for that pot of gold and the country house with the roses round the door.’

‘They start looking for things we’ve been promising them for twenty years. That’s the truth of it.’

‘Who knows what makes these crazy bastards do it?’ said Cruyer. ‘I’ve spent half my life trying to understand their motivation.’ He looked out of the window. Hard sunlight sidelighting the lime trees, dark blue sky with just a few smears of cirrus very high. ‘And I’m still no nearer knowing what makes any of them tick.’

‘There comes a time when you have to let them go,’ I said.

He touched his lips; or was he kissing his fingertips, or maybe tasting the gin that he’d spilled on his fingers. ‘Lord Moran’s theory, you mean? I seem to remember he divided men into four classes. Those who were never afraid, those who were afraid but never showed it, those who were afraid and showed it but carried on with their job, and the fourth group – men who were afraid and shirked. Where does Brahms Four fit in there?’

‘I don’t know,’ I said. How the hell can you explain to a man like Cruyer what it’s like to be afraid day and night, year after year? What had Cruyer ever had to fear, beyond a close scrutiny of his expense accounts?

‘Well, he’s got to stay there for the time being, and there’s an end to it.’

‘So why was I sent to receive him?’

‘He was acting up, Bernard. He threw a little tantrum. You know the way these chaps can be at times. He threatened to walk out on us, but the crisis passed. Threatened to use an old forged US passport and march out through Checkpoint Charlie.’

‘So I was there to hold him?’

‘Couldn’t have a hue and cry, could we? Couldn’t give his name to the civil police and send teleprinter messages to the boats and airports.’ He unlocked the window and strained to open it. It had been closed all winter and now it took all Cruyer’s strength to unstick it. ‘Ah, a whiff of London diesel. That’s better,’ he said as there came a movement of chilly air. ‘But he’s still proving difficult. He’s not giving us the regular flow of information. He threatens to stop altogether.’

‘And you … what are you threatening?’

‘Threats are not my style, Bernard. I’m simply asking him to stay there for two more years and help us get someone else into place. Ye gods! Do you know how much money he’s squeezed out of us over the past five years?’

‘As long as you don’t want me to go,’ I said. ‘My face is too well known over there. And I’m getting too bloody short-winded for any strong-arm stuff.’

‘We’ve plenty of people available, Bernard. No need for senior staff to take risks. And anyway, if things went really sour on us, we’d need someone from Frankfurt.’

‘That has a nasty ring to it, Dicky. What kind of someone would we need from Frankfurt?’

Cruyer sniffed. ‘No need to draw you a diagram, old man. If Bee Four really started thinking of spilling the beans to the Normannenstrasse boys, we’d have to move fast.’

‘Expedient demise?’ I said, keeping my voice level and my face expressionless.

Cruyer became a fraction uncomfortable. ‘We’d have to move fast. We’d have to do whatever the team on the spot thought necessary. You know how these things go. And XPD can never be ruled out.’

‘This is one of our own people, Dicky. This is an old man who has served the Department for over twenty years.’

‘And all we’re asking,’ said Cruyer with exaggerated patience, ‘is for him to go on serving us in the same way. What happens if he goes off his head and wants to betray us is conjecture – pointless conjecture.’

‘We earn our living from conjecture,’ I said. ‘And it makes me wonder what I would have to do to have “someone from Frankfurt” come along to get me ready for that big debriefing in the sky.’

Cruyer laughed. ‘You always were a card!’ he said. ‘You wait until I tell the old man that one.’

‘Any more of that delicious gin?’

He took the glass from my outstretched hand. ‘Leave Brahms Four to Frank Harrington and the Berlin Field Unit, Bernard. You’re not a German, you’re not a field agent any longer, and you are far, far too old.’

He put a little gin in my glass and added ice, using claw-shaped silver tongs. ‘Let’s talk about something more cheerful,’ he said over his shoulder.

‘In that case, Dicky, what about my new car allowance? The cashier won’t do anything without the paperwork.’

‘Leave it to my secretary.’

‘I’ve filled in the forms already,’ I told him. ‘I’ve got them with me, as a matter of fact. They just need your signature … two copies.’ I placed them on the corner of his desk and gave him the pen from his ornate desk set.

‘This car will be too big for you,’ he muttered while pretending the pen was not marking properly. ‘You’ll be sorry you didn’t opt for something more compact.’ I gave him my plastic ballpoint, and after he’d signed I looked at the signature before putting the forms in my pocket. It was perfect timing, I suppose.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/len-deighton/berlin-game/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Len Deighton

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Шпионские детективы

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 246.16 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 28.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Long-awaited reissue of the first part of the classic spy trilogy, GAME, SET and MATCH, when the Berlin Wall divided not just a city but a world.East is East and West is West – and they meet in Berlin…He was the best source the Department ever had, but now he desperately wanted to come over the Wall. ‘Brahms Four’ was certain a high-ranking mole was set to betray him. There was only one Englishman he trusted any more: someone from the old days.So they decided to put Bernard Samson back into the field after five sedentary years of flying a desk.The field is Berlin.The game is as baffling, treacherous and lethal as ever…