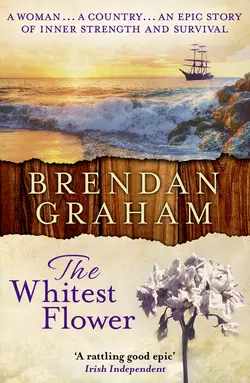

The Whitest Flower

Brendan Graham

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 463.26 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Rich and epic Historical Fiction set against the backdrop of the Great Famine. Perfect for fans of Winston Graham and Ken Follett.It is August 1845. In Dublin’s Botanic Gardens, Phytophora infestans is discovered for the first time. The bacteria blooms throughout the country, blighting potato crops and creating what becomes known as the Great Famine: an event of holocaust proportions that affects every man, woman and child in Ireland.Ellen O’Malley is one such victim. As the Blight ravages the land, Ellen loses her husband. Alone and vulnerable, she is duped into going to Australia to seek a better life, leaving three of her beloved children behind. Travelling aboard a coffin ship, she arrives emaciated and ill with her new baby. But the country proves a harsh and brutal landscape and a change in fortunes seems further away than ever. But Ellen, a woman with an indomitable spirit, is determined to rise above her oppression and bring her family together once more.