The Element of Fire

Brendan Graham

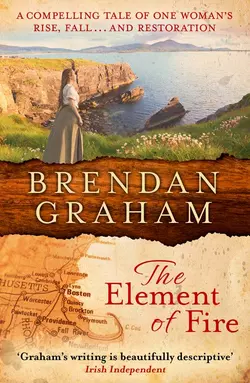

Rich and epic Historical Fiction set against the backdrop of the Great Famine. Perfect for fans of Winston Graham and Ken Follett.Boston in the 1850s is the hub of the universe: gateway to America’s temples of commerce and learning; liberal, sophisticated – the very best place in all of the New World for a woman to be.After being ripped from her homeland of Ireland, thrust into the harsh and unforgiving landscape of Australia, it is here that Ellen O’Malley hopes to find the stability of a new life and a new love; Lavelle, the man who adores her.But Ellen, desperate to shake off the Old World, is driven by her own demons to put everything at risk. And Boston, on the brink of Civil War, seems only to mirror her own conflict, to sound the knell of her own battle for survival.A powerful and compelling tale of lives and loves dislocated, The Element of Fire captures emotions as timeless as life itself.

BRENDAN GRAHAM

The Element of Fire

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_cab9264d-251e-5bd0-ae21-2b12f010f5d9)

HarperCollinsPublishers The News Building 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

This edition 2016

First published in Great Britain by

HarperCollinsPublishers 2001

Copyright © Brendan Graham 2001

Brendan Graham asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Although this work is partly based on real historical events, the main characters portrayed therein are entirely the work of the author’s imagination.

Fair-Haired Boy - Words and Music by Brendan Graham © Brendan Graham (world exc. Eire) / Peermusic (UK) Ltd. (Eire)

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780006513964

Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2016 ISBN: 9780007401109

Version: 2016-01-19

DEDICATION (#ulink_34668e1a-84fc-596c-9ea4-b05a4b4d620d)

Dedicated to the memory of

‘The Coot’,

Fr. Henry Flanagan O.P., Newbridge College

(1918–1992)

Sculptor, musician, teacher, friend

CONTENTS

Cover (#u8d479b98-81c2-5f54-8b6f-8d037b995651)

Title Page (#u75cd08a5-7b82-53d4-99a2-436e7af44dd4)

Copyright (#u7eccd35b-b898-5f22-a663-fa751857bbd7)

Dedication (#u9bee5883-8984-52ac-ae94-fae124de3530)

1 (#u9ae307c5-f454-522d-8d4e-c3b18aa61339)

2 (#u488cd4b3-09de-54d6-8910-6a48e1ec3fdc)

3 (#uf20d5270-f3f3-5102-a974-655e5ce0df2a)

4 (#ub8efce00-9ccb-505f-9d82-def45d0841b5)

5 (#u9712ec78-0aab-5439-86b9-713531cd256b)

6 (#u803775d1-cfa0-5599-b8e1-d8ac55a22ed4)

7 (#u33766165-4308-5b4a-9f75-3e42e9723b48)

8 (#ue71813d0-38ca-50ea-ae4c-b9dac243d4bd)

9 (#ua96f652f-14b1-5f2c-84b3-de4c921a4390)

10 (#uca92a75b-ab2d-534e-978f-1972672c4b2f)

11 (#uc511f4a0-98fd-5cec-b7d3-dae2cd32d234)

12 (#u93e57763-85ee-5e8d-b4c2-e16563e4a4d9)

13 (#u7b2a41b4-a086-5397-886f-a54187946153)

14 (#ufa8dcd07-6472-5367-9005-75354584ce95)

15 (#litres_trial_promo)

16 (#litres_trial_promo)

17 (#litres_trial_promo)

18 (#litres_trial_promo)

19 (#litres_trial_promo)

20 (#litres_trial_promo)

21 (#litres_trial_promo)

22 (#litres_trial_promo)

23 (#litres_trial_promo)

24 (#litres_trial_promo)

25 (#litres_trial_promo)

26 (#litres_trial_promo)

27 (#litres_trial_promo)

28 (#litres_trial_promo)

29 (#litres_trial_promo)

30 (#litres_trial_promo)

31 (#litres_trial_promo)

32 (#litres_trial_promo)

33 (#litres_trial_promo)

34 (#litres_trial_promo)

35 (#litres_trial_promo)

36 (#litres_trial_promo)

37 (#litres_trial_promo)

38 (#litres_trial_promo)

39 (#litres_trial_promo)

40 (#litres_trial_promo)

41 (#litres_trial_promo)

42 (#litres_trial_promo)

43 (#litres_trial_promo)

44 (#litres_trial_promo)

45 (#litres_trial_promo)

46 (#litres_trial_promo)

47 (#litres_trial_promo)

48 (#litres_trial_promo)

49 (#litres_trial_promo)

50 (#litres_trial_promo)

51 (#litres_trial_promo)

52 (#litres_trial_promo)

53 (#litres_trial_promo)

54 (#litres_trial_promo)

55 (#litres_trial_promo)

56 (#litres_trial_promo)

57 (#litres_trial_promo)

58 (#litres_trial_promo)

59 (#litres_trial_promo)

60 (#litres_trial_promo)

61 (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Recommended Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

‘The element of fire is quite put out;

The sun is lost, and th’ earth …’

‘An Anatomy of the World’

JOHN DONNE (1572–1631)

1 (#ulink_92d5f17a-2a1b-59db-a3b8-2af6edd29021)

1848 – Ireland

It was a grand day for a funeral.

A grand August day, Faherty thought.

The coachman, a thin, normally talkative fellow, with a tic in his left eye, held back now. Cap in hand, he waited, a respectful distance from the graveside.

He had brought them here, deep into the mountains and lakes of this remote Maamtrasna valley. The red-haired woman, her twin daughters, one dead, one alive; the son, and the orphan waif, silent as a prayer, beside him.

The silent one was a mystery to him. A week ago – the first time he had brought the woman back here from the ship at Westport – the girl had appeared out of nowhere and attached herself to them, running near naked alongside his carriage for miles. Not a word out of her mouth, not even begging.

He wouldn’t have stopped if it hadn’t been for the woman. She had taken pity on the girl, saved her from almost certain death. Since then, all through the last few days, she had been like a shadow to the woman, quiet as a nun. God knows, he decided, seeing the woman kneeling over the grave – settling into it the tiny white flowers of the potato plant – someone would want to watch over her. It was surely a strange thing to do – potato flowers on a grave. The way she ran down from the hillock here. Ran, barefooted to the bare-acred field, on past the tumbled cabins and, like that, snatched up a fistful of the flowers from the derelict potato beds. Before that the child’s shawl – ‘Annie’s shawl’, she called it – must be another one she lost – twined it round the hands of the little dead one, like rosary beads.

Now her fine, emerald-green American dress was ruined with kneeling in the clay, but she didn’t seem to notice. Just kept repeating the child’s name over and over: ‘Katie! Katie! Oh, Katie a stór!’ Faherty wondered what she had been doing beyond in America, with her three children here? Not knowing whether they were dead or alive. He watched the shape of her stretch backwards. She was hardly the thirty years out – a fine woman. He turned his head slightly, so as not to be watching her that way.

Out of the corner of his good right eye, he glanced back along the curl of the valley, with its lake of green glistening islands. There wasn’t much here for her – a few patches of hungry grass. Not a beast in a field. Hard to get a morsel of food out of a place like this – even before the potato rot. Nothing but rocks and stones and water everywhere, as Faherty saw it.

The sun was bothering him, causing his left eye to jump even more.

Hard on her though, sailing all this way to find them, and then one of them up and dying, just when she thought she had them safe. Hard on the little one left too – she must be only the nine or ten years, same as the other little one they were burying. A split pair they were – one taken, one left behind, the two of them the spit of the mother, hair like it was spun out of hers.

The boy was a biteen older, maybe two or three years. Distant from the mother – for leaving them, Faherty supposed. Didn’t look like her either, dark, must have taken after the father. But then, what else could the woman have done? Her husband already put into this spot and their cabin thrown down. What had she left here, only the gossoors and no way of supporting them? The boy would understand in time – give him a few years, and a few knocks in life. He’d understand all right. Still, it must have been hard.

The woman was straightening, dusting down her dress, wiping the earth from her feet, readying to go. She was tall, for a woman. His eye, practised for horse flesh, put her at seventeen hands, maybe even the seventeen and a half. A hand or two above his own five feet four inches. A fine ainnir of a woman. She wouldn’t wait a widow long, Faherty thought. He crossed himself, slid on his cap again, fell in behind the silent girl as they descended the burial place, the same as they’d come up, in single file, the boy leading. Next, the living twin, followed by the mother, then the girl and himself.

It was a strange thing the way, when they had set out on the journey here … the way she had carried the child, not letting on at first that she was dead at all, just bad with the fever. He supposed the woman had her reasons. In case they’d take the girl from her, throw her into the lime pit, maybe. Faherty didn’t know what in God’s name she wanted to be hauling all the way out here for, to this wild place, making a thing of it. Sure, weren’t people dying like flies on every side, on account of the Famine, half of them getting no right burial at all. Faherty was well used to death by now. When you were dead, you were dead. She could have buried the child back in Westport, in the Rocky, and saved them all this trouble. The Rocky, if it was a quarry, was consecrated to take the fevered dead. Sure, wasn’t half the countryside already flung into it!

He picked his way down the Crucán, the sweep of the Maamtrasna valley unnoticed before him.

Nell had strayed from where he’d left her, snaffling the sweet grass of the long acre which bordered the mountain pass road. The horse was tired from all the travelling. He patted her neck, relieved she hadn’t wandered too far. Back here, in the valleys, a wandering horse wouldn’t last long.

‘I’m sorry, Nell …’ he whispered into the animal’s ear, so the woman wouldn’t hear him, ‘… dragging you all the way out here where they’d eat you, quick as look at you.’

As they rounded the bend, skirting the edge of the lake, Ellen held the three of them into her: Patrick crooked in her right arm, Mary in the near reach of her left, half-lying across her, half-smothered in the lap of her dress. The girl then beyond Mary, but within the circle of what remained of the family. Ellen watched the back of Faherty’s head, rolling from side to side as it did when he spoke. Now, he was saying nothing, unless talking to himself.

She looked out at the Mask, probably seeing the lake for the last time, not caring if she never saw it again. Nor the valley, hanging there around it, so green, so empty, so full of death, the sun spilling over it as if nothing in the world was wrong. As if it were the Plains of Heaven.

Faherty’s head stopped lolling for a moment. She watched it half-turn towards her.

‘It was a grand day …’

She hardly heard him, her attention drawn to his jumping eyelid. It must be a nervous thing. He was probably nervous as a child, she thought.

‘… a grand day for a funeral, ma’am!’ he said, meaning it.

2 (#ulink_5f61446a-4afe-5750-b5e4-c20269ee8437)

For the rest of the journey around the lake she never spoke. Faherty too was silent.

He never heard her even weep. It was all too much for her, he thought. Sorrow and guilt – a bad mixture. If she keened it out of herself, got shut of the grief, it would be better for her. But after this, it would be easier. Beyond in America with only the two to care for – and the silent one, if she took her with them? At least they had a chance, somewhere to go to, out of this God-forsaken place. Not like the poor devils here, wandering the roads scouring for scraps, arms and legs stuck out of them like scarecrows. Eyes burned into the sockets with fever. No sound. Only the bit of a breeze rattling through bared ribs. Wherever they were headed it didn’t matter, they’d get nothing, neither food nor sympathy. It was the same all over – a land full of nothing. The only hope a quick leaving of this life and Paradise in the next, if they were lucky.

Faherty wondered about Paradise, the Garden of Eden. Was it like the big houses once were? Hanging gardens; carpets of flowers; servants at every turn; fruit on every tree. And long rows of lazy beds, the fat lumper potatoes tumbling out of them, begging to be eaten. He wanted to ask her was America like that.

Mairteen Tom Anthony, a big bodalach of a fellow from the foot of the Reek, once told him how the buildings were so tall in New York, that when he first went out there the roof of his mouth got sunburnt from standing all of a gám looking up at them. Faherty wasn’t sure if Mairteen was tricking him or not. America turned people into tricksters – even an amadán like Mairteen Tom.

Leave her be, he decided.

It was still light when Nell edged them past the conical-shaped reek of Croagh Patrick, so she made Faherty bring them straight to Westport Quay. As they passed the workhouse gates hundreds clamoured, seeking admittance. Hundreds more, near naked and starving, sought to clamber over the top of these, calling for ‘relief tickets’ that would grant them soup; sole sustenance for one more day.

‘There must be three thousand inside, if there’s a soul,’ Faherty opined, ‘and as many more outside wanting in.’

They sloped down Boffin Street, past the boatmen’s houses and the gaunt Custom House still, in the reign of Victoria, designated the ‘King’s Stores’. Here, fuelled by hunger, six hundred in rags milled in desperate hope, battened back by militiamen. Nearby, cart-followers, employed to protect the grain when being transported to the town’s merchants, waited, slinking on the margins of the famished until called to their cold duty.

Another angry crowd sent up cries of dismay as a ship from Marseille discharged its cargo of wheat, beans and chestnuts, while behind a clipper of Constantinople lay by, bursting with corn from New Orleans, and flanked by Her Majesty’s revenue cruisers. Behind the ships were the island drumlins of Clew Bay – giant hump-backed whales, silhouetted against the purple and crimson of the dying day. Ellen leapt from Faherty’s carriage. One of the ships must be Atlantic-bound.

Westport Quay throbbed with all the mixed ingredients of quay life. Pampered gentry and a starving commonality jostled equally with tidewaiters and landwaiters, while elbow to shoulder with the herring- and oystermen of Clew Bay, shipping agents of indifferent character plied their raucous trade.

‘Passage to Amerikay!’ they called, thrusting beckoning circulars into the hands of all who would snatch them from the surrounding chaos. She took one.

At WESTPORT For PHILADELPHIA To sail about 10

October The splendid first-class Copper-fastened, British-built ship GREAT BRITAIN.

She pushed it back against the agent’s hand. ‘Today … these ships … America?’ she shouted above the din. The agent, a puffy little fellow in an important hat, gave her the once-over.

‘Yes ma’am, to the exotic city of New Orleans,’ – as if he’d ever been there – face creasing into a red-veined smile. A well-heeled mark, this one – a bit soiled about the hem, but had the wherewithal for passage, he’d wager, unlike most of them here.

‘No … Boston, I want Boston!’ she impressed on him, impatient that he didn’t already know.

‘Boston, New Orleans, Philadelphia – it’s all America!’ he expounded – what did the woman care? ‘Four to a berth, splendid provisions and a quart o’ water a day. Is it just yourself, ma’am?’

She left the sound of him puffing away behind her, and through the pandemonium eventually made her way to the offices of John Reid, Jun. & Co., Ship Agents.

Mr John Reid, Jun., an affable-looking man in his fifties, had ‘no intelligence, in the coming weeks, of any ship Boston-bound. But we are sometimes surprised by what the tide brings in,’ he informed her, helpfully. Her only course of action, he advised, was to keep daily watch at the quay and enquire of him regularly. He could promise her ‘a ship fitted with every attention to the comfort of passengers for Québec, before three weeks was out’, adding, ‘Québec being but a tolerable land journey from Boston’.

She was dismayed. Here she was, her two remaining children secure, and no way out of Ireland. She wondered about Québec, about taking a chance, but feared for the ship Mr Reid had described as ‘fitted with every attention to the comfort of passengers’. She had seen these ‘comfort of passengers’ ships before. ‘Coffin ships’ and rightly named so. Then to land on Québec’s quarantine island – Grosse île, with its seeping fever sheds. She could not subject them to that, she told him, so declining his suggestion.

3 (#ulink_940e1399-1ad6-53ce-a24d-873866eae8cd)

‘Ne’er mind, ma’am, something will crop up,’ Faherty tried to console her with, when she found them again. ‘I’ll take you to The Inn on the North Mall,’ he offered. ‘You can rest up there a while.’ He imagined a lady like her wouldn’t be shy the tally for the innkeeper, his second cousin. ‘It’s for ever full with agents and customs men. I’ll put word with the owner, a dacent man,’ he said, without naming him, ‘to keep an ear out on their talk.’

Again Nell carted them, this time up against the slope of Boffin Street, through the town’s Octagon and past the Market House, a fine, ashlar-built, two-storey, with pediment roof and louvred bell cote.

It reminded her of Faneuil Hall, in Boston’s Quincy Market. But Boston was a city much advanced on Westport. In turn the Octagon, with its imposing Doric column, oddly at variance with the inched-out life of those below it.

She felt the children dig in closer to her as they passed the stench of the Shambles where the butchers of James Street rendered carcasses. Faherty yanked Nell to the right, away from the gated entrance to Westport House, home to Lord Sligo, and took them instead along the North Mall.

On this tree-lined boulevard, with its leafy riverside, the poor huddled, congregating outside the place to which Nell delivered them. Faherty nudged the horse forward, shouting at those who blocked their progress, ‘Get back there! Let the lady through! She’s had a sore loss this day!’

Ellen, aware of the pitiful, near-death state in which most of his listeners were, and embarrassed by Faherty’s words, bowed her head. It didn’t seem to bother Faherty, who skipped down from his perch, tied Nell to the hitching-post and then helped her and the children alight.

The near-dead gaped at them, shuffling out a space through which they could pass. Some made the sign of the cross as she approached, respectful of her loss.

Faherty gentled her in under the limestone porch, solicitous for her well-being, and bade her wait while he sought the keeper.

Inside was a sprinkling of red-faced jobbers, stout sticks in their paw-like hands, the stain of dung on their boots. Beef-men in this ‘town of the beeves’ – Cathair na Mart – as she knew it by name. She wondered who it was bought their beef, in these straitened times? Merchants with money, she supposed. Some of the beeves would end up in the Shambles they had just passed. Some would go out on the hoof, heifered over in ships to help drive those who drove the hungry machines of England’s great industrial towns. Not a morsel would find its way to the empty mouths of those outside.

The tug at her arm recalled her from England’s mill towns. It was Mary. ‘Patrick’s not here!’

Ellen spun around. The boy was nowhere to be seen. She bade Mary and the silent girl wait and rushed for the crowds outside, impervious to everything except that she must not lose him now. Down the Mall she saw him some twenty paces away, on his knees in company with a ragged boy, scarce older than himself. She ran to him, ever fearful of … something – she didn’t know what.

She reached him, relieved to see he was not harmed. ‘Patrick, what …?’

‘I was only helping him,’ Patrick said, defensively.

The other boy, a tattered urchin with vacant stare, backed away, afraid of what this frantic and well-dressed lady might do to him. ‘Tá brón orm, ma’am’ – ‘I’m sorry, ma’am’ – he said, fearfully, in a mixture of Irish and his only other word of English apart from ‘sir’.

She spoke to him in Irish. This seemed to help him be less cowed. Nevertheless, he kept his eyes thrown down as he told his story.

They lived five miles out on the Louisburgh road. His parents, both stricken with Famine fever, had hunted him and his two younger brothers, eight and six years, ‘to Westport for the soup-tickets’. So the three had set off, he in charge. At the workhouse, he was too small to make headway against the clamouring crowds. Instead, he had followed the flayed carcass of an ass, bound for human consumption, and stolen some off-cuts, which he and his brothers had eaten. After sleeping in one of the town’s side alleys, he had awoken, planning to come here to The Inn, the headquarters of the Relief Works’ engineer, ‘looking for work, to get the soup that way, ma’am’, he explained.

Unable to arouse his two younger brothers, he thought they still slept, ‘sickened by the ass-meat’, eventually realizing they lay dead beside him. Then he had stolen a sack, put their bodies inside and carried it over his shoulder ‘to get them buried with prayers’. At the Catholic church on the opposite South Mall, he had sneaked in the doors on the tail of a funeral: ‘for a respectable woman like yourself, ma’am – she was in a coffin’. But, while the church-bell tolled the passing of the ‘respectable woman’, he had been ejected on to the streets with his uncoffined brothers. Again, he had carried his sack back to The Inn, hoping against hope to get food. Food that would give him enough strength to find a burial place for his dead siblings, ‘till I fell in a heap with the hunger!’

That was what Patrick had seen – the boy collapsing, the sack flung open on the road, from within it the two small bodies revealed. Not that he hadn’t seen plenty dead from want before. It had to do with Katie, Ellen knew.

She made to approach the boy. He, still afraid that he had caused some bother to her, backed away. She halted, hunkered down, then called to him. Slowly, he approached, head down, arms crossed in front, a hang-dog look on him as if waiting to be beaten. She reached out and enfolded him.

‘You’re a brave little maneen,’ she said, feeling his skin and bone, his frightened heart, within her arms. ‘We’ll get them buried. And we’ll get some soup for you,’ she comforted, wondering as she spoke, what in Heaven’s name she would do with him then.

After a few moments, she released him and went to Patrick. ‘You did right, Patrick, to go and help him,’ she said, and held her son against her. ‘I was so afraid I’d lost you again.’

Patrick made no reply, neither accepting nor denying her embrace. She was a long way yet from his forgiveness.

Grabbing the sack, she twisted the neck of it closed, not bearing to look inside. The weight of the corpses within resisted her, each tumbling for its own space, not wanting to be carcassed together in death. She didn’t know how the boy had managed to carry it for so long.

Then Faherty was beside her. ‘Ma’am, are you all right?’ he panted, all of a flap, seeing her struggle with the sack.

‘We need your services again, Mr Faherty,’ she said grimly.

Puzzled, he looked at her, looked from Patrick to the boy, then to the sack, finally back to her, his eye jumping furiously all the time. She saw the realization dawn on his face, the ferret-like look he darted her way.

‘You’ll be paid, of course!’ she answered his unspoken question.

‘Right, ma’am, I’ll fetch Nell.’ He made to go, all concern for her well-being now abated. Money was to be made. He turned. ‘And what about him, ma’am?’ He nodded towards the boy beside her: ‘You can’t save all of ’em.’

‘I know, Mr Faherty. I know!’ she said resignedly. Of course she couldn’t take the boy with her. She would have to release him again on to the streets, to take his slim chances. How long it would be before he, too, joined his brothers, either coffined or uncoffined, she didn’t know.

Later, in the bathroom down the hall, she filled the big glazed tub with buckets of steaming water. She dipped her elbow in. Maybe it was too hot. She waited until it was barely tolerable then went for Patrick, scuttling him along the corridor in case some dung-stained jobber got in ahead of them. She undressed him and bustled him into the tub, all the while Patrick protesting strongly at this forced intimacy between them and her all too obvious intentions.

‘I’m clean enough! I don’t need you to wash me!’ elicited no sympathy. She was taking no chances after the episode with the boy and his dead brothers – who knew what they carried? She rolled up her sleeves and scrubbed him to within an inch of his life, until his skin was red-raw. He thrashed about in the water trying to get away from her but to no avail. She did not relent until she was satisfied he was ‘clean’, until she had found every nook and cranny of his body. Then, lugging him by each earlobe in turn, she stuck long sudsy fingers into his ears, to ‘rinse’ them. When she had finished he was like a skinned tomato. Sullen, jiggling his shoulders so as not to allow her to dry him with the towelling cloth. She gave up, threw her coat over his shoulders and led him back to the room. ‘Dry yourself, then,’ she ordered him.

The two girls she put together into the tub. She was not so worried about them. But even from Katie they might have taken something; and much as she didn’t want to think of it, she had to be careful about that too. Disease passed from person to person, even from the dead to the living. Ellen thought the girl would be shy about letting her touch her. This proved not to be the case. Mary, though, seemed to recoil from the girl, not wanting their arms and legs to touch, get entangled. Maybe it was a mistake putting them in the bath together, so soon after Katie. She was as gentle as she could be with Mary, kept talking to her.

‘Katie is with the angels in Heaven, with the baby Jesus … with –’ She paused, thinking of Michael, the hot steam of the tub in her eyes. ‘I was too late … too late a stór … but they’re looking down on us now … it was hard, Mary, I know … and on Patrick … and Katie too, with your poor father laid down on the Crucán and me fled to Australia. What must have been going through your little minds?’ Maybe it would have been better if she had taken Annie and with the three of them, crawled into some ditch till the hunger took them instead of her splitting from them. But how could she have watched them waste away beside her, picked at by ravens, their little minds going strange with the want of a few boiled nettles, or the flesh of a dog. She thought of the boy and his brothers – or any poor manged beast that would stray their way. She had had to go, it was no choice in the end – leave them and they had some chance of living, stay and they all would surely die.

Mary, head bent, said nothing, her hair streaming down into the water, red, lifeless ribbons. What could she say to the child? She pulled back Mary’s hair, wrung it out, plaited it behind her head.

‘God must have smiled … when He took Katie. He must have wanted her awful badly …’

Mary turned her face. ‘Then why did He leave me?’ she asked limply, boiling it all down to the crucial question.

‘I don’t know, Mary,’ she answered. ‘There were times when I prayed He’d take all of us. He must have some great plan for you in this life,’ she added, without any great conviction.

How could the child understand, when she couldn’t understand it herself – the cruelty of it – snatching Katie from them at the last moment. She fumbled in her pocket, drew out the rosary beads.

‘The only thing is to pray, Mary; when nothing makes sense the only thing is to pray, Mary,’ she repeated.

Already on her knees, arms resting on the bath, Ellen blessed herself.

‘The First Joyful Mystery, the … the Annunciation,’ she began.

They had to have hope in their hearts. The sorrow would never leave, she knew, and maybe there would never be full joy in this life. But they had to have hope, keep the Christ-child in their hearts.

She and Mary passed the Mysteries back and forth between themselves, each leading the first part of the Our Father, the Hail Marys and the Glory be to the Father as it was their turn. Once, before the Famine, there were five of them – a Mystery each.

The silent girl gave no hint that she had ever previously partaken of such family devotion, merely exhibiting a curious respectfulness as the prayers went between Ellen and Mary through the veil of bath-vapour – the mists of Heaven. Ellen’s clothes were sodden, her face bathed in steam, the small hard beads perspiring in her hands. The great thing about prayer was that you didn’t have to talk to a person while you prayed with them. Yet souls were joined talking to each other, while they talked to God. She beaded the last of the fifty Hail Marys. There was only so much time for prayers and she whooshed the two out of the tub before they could get cold.

Afterwards, she boiled all of the clothes they had worn, along with her own, before at last climbing into the tub herself. It was a blessed relief. When she had finished rinsing out her hair she lay there, head back on the rim of the tub, her eyes closed. Everyone and everything done for. A little snatch of time to be on her own. Just her and Katie.

The memories flooded back to her. How when she’d send Katie and Mary to the side of the hill for water, they would become distracted, forget. Instead, would lie face-down on the cooling slab of the spring well, watching each other’s reflections in the clear water. Then, when she called them they would scamper down the hill to her, pulling the bucket this way and that until half its contents was left behind them. The times when she did the Lessons, teaching them at her knee what she had learned at her father’s knee, passing it on. While Mary would reflect on what she had learned, Katie just couldn’t. Always bursting with questions, one tumbling out after the other, mad to know only about Grace O’Malley, the pirate queen of Clew Bay, or Cromwell and his slaughtering Roundheads. God, how Katie had tried her patience at times! The evenings, when as a family they would kneel to say the rosary, Katie’s elbowing of Mary every time the name of the Mother of God was mentioned, which was often! At Samhain once when the spirits of the dead came back to the valley, Katie had thrown one of the bonfire’s burning embers into the sky. No amount of argument could shake her belief but that she had hit an ‘evil spirit’ with it.

That was Katie, a firebrand herself, filled to the brim with life. But she had the other side too; like the time she had dashed to the steep edge of the mountain as they crossed down to Finny for Mass. It had put the heart crossways in Ellen. But Katie had returned safely and clutching a fistful of purple and yellow wildflowers, a gift for her mother.

Her fondest memory of Katie was of the time when Annie was born. Katie had crept to her side, to be the first one to see ‘my new little sister’. Like an angel touching starlight, one tentative finger had stretched out to touch Annie’s cheek. How Ellen herself had cried at the beauty of the moment, then laughed at her own foolishness. Katie, as always, asking the ever-pertinent question. ‘A Mhamaí, why are you crying when you’re laughing?’ And she couldn’t answer her. They had lain there together, she and Katie and Annie, into the gathering dawn; touching, whispering, rapt in wonder until the others came. Both of them now snatched from her, Annie in far-off Australia, Katie on her own doorstep.

‘You in there!’ The loud rap at the door startled Ellen. ‘You’ve been there all night, we have others waiting!’ The gruff voice of Faherty’s cousin was matched by further rapping.

‘I’m sorry,’ she called back, clambering out of the tub, ‘I’m coming.’

She was relieved when she opened the door to find he had gone downstairs. Briskly she padded along the corridor, marking it with her wet footprints, the only sound ringing in her ears, not that of the gruff innkeeper but a child’s question.

‘Can we make wonder last, a Mhamaí?’

And her answer, those two and a half years ago. ‘Yes, Katie, we can.’

Back in the room, Patrick, Mary and the girl were already asleep. She dried herself freely, nevertheless, keeping at a discreet distance from the window in The Inn’s west wing. The window looked out across the Carrowbeg river. Directly opposite she could see St Mary’s Church, with its imposing parapet. The thought of the boy with the sack being evicted from the House of God because of his wretched condition angered her. Why had she felt responsible for the boy – as she had for the silent girl? Why for some and not for others, when thousands were dying? Faherty had told her thirty-nine poor souls had received the last sacraments in that day alone.

‘And it’s the same every day, ma’am. Monday to Sunday. They say there’s thirty thousand of the destitute getting outdoor relief around here – they’ll be joining with them soon enough.’

She could well believe it. Thirty thousand in one small area. She wondered if there was any hope for the country at all. But why didn’t she feel as bad about these, about the nameless hordes, as she did about the boy? She had never asked his name. That way, he was just a boy, any boy. But she was ridden with guilt when after giving him some food and a few coins with which to send him off, he had thanked her saying, ‘I’ll pray for you, ma’am.’ Faherty was right, she couldn’t save them all. But what would the child do, where would he go? For how long would he survive?

The limestone façade of St Mary’s looked back white-faced at her from the South Mall. Nothing much had changed since she had left Ireland. If you had money you lived proper and you died proper, as Faherty might have put it. You had the Church behind you. Otherwise it was a pauper’s life and a pauper’s grave.

This thought reminded her she needed to be careful with the money. She had depleted what she had carefully squirrelled away over many months in Boston, by coming to Ireland. Now, with The Inn, and who knew for how long, and the extra cost to Faherty for the two coffins, she had eaten further into her reserves. The silent girl could only come with them because Katie wasn’t. If they had long to wait in Westport, Ellen might not even be able to afford that passage. She would be forced to leave the girl behind. At one stage, she had almost decided to disentangle herself from the girl and give her to the nuns, if they’d take her.

The waif, who watched and shadowed her everywhere, seemed to be a manifestation of the past dogging her, a spectre of loss, separation, Famine. It unnerved her the way the girl never asked anything of her, just was there like a conscience. But, given a little time, she might make a companion for Mary. Not that anybody could replace Katie; it wasn’t that. But maybe Mary might find some echo of her own unvoiced loss in the silence of the mute girl, some small consolation in her companionship on the long journey across the Atlantic.

Now, Ellen prayed across the waters of the Carrowbeg to the House of God that she would not have to change that decision. She closed her mind from even having to think about it. Instead, she tried to recall what it was Faherty had said about the church opposite. About the inscription from the Bible that its foundation stone carried?

‘This is an awful place. The House of God.’

Faherty knew all these things.

4 (#ulink_971cfb93-34ff-5ea7-9ff8-21cfd1948d61)

The days dragged by. Each day she trudged with the children to the quayside and scanned out along Clew Bay for the tell-tale line against the sky. Each day they returned dispirited, almost as much by what they had witnessed on the way, as by the lack of a ship. Was there to be no let up in the calamity? The scenes of despair and deprivation seemed to her to have worsened. Droop-limbed skeletons of men – and women – hauled turf on their backs through the streets, once work only for beasts of burden. When she mentioned this at The Inn, they laughed at her naïveté.

‘There’s not an ass left in Westport that hasn’t been first flayed for the eightpence its pelt will bring, then its hindquarters eaten,’ a well-cushioned jobber jibed. ‘Now the peasants who sold them have to make asses of themselves!’

She was shocked at the indifference of the commercial classes to the plight of ‘the peasants’.

Nervous of everything, she kept the children close by and was cross with them if they wandered, terrified that she’d lose them. That they’d be swallowed in the hordes of the famished who filled the streets with the smell of death and the excrement of bodies forced to feed inwardly upon themselves.

Once she traipsed them with her to Croagh Patrick. They climbed to where they could look across the dotted archipelago of the bay, out past the Clare Island lighthouse. She could see no tall ships, only boats far out, maybe tobacco smugglers, or those ferrying the contraband Geneva, an alcoholic liquor flavoured with juniper and available from under the counter – if asked for – at The Inn.

They climbed higher for better vantage, Ellen straining her eyes against the gold and green of sun and sea. Here, on this age-old mountain, St Patrick had fasted for forty days and forty nights. ‘Those who worship the Sun shall go in misery … but we who worship Christ, the true Sun, will never perish.’ In the writing of his Confession the saint had denounced the sun and its worshippers. Now she prayed to the sun to bring them a ship. Sun-up or sun-down, it didn’t matter, as long as it came. To the west her eye caught a rib of white stone rising heavenwards against the bulk of the mountain. A ‘Famine wall’ going nowhere, built on the Relief Works to exact moral recompense from the starving stone-carriers. They in turn given ‘relief’; a few pence in pay, a handful of soup-tickets.

She remembered how on the last Sunday of summer, Reek Sunday, as it was widely known, the Clogdubh – the Black Bell of St Patrick – was brought there for weary pilgrims to kiss, for a penny. Black from the holy man pelting it at devils, they said. She had never kissed it. For tuppence, those afflicted with rheumatism might pass it three times around the body, for relief. Another superstition of the shackling kind that bred paupers to pay priests. Like the legends about the reek itself. Legends, she guessed, grown to feed misery and repentance, to keep the people out of the sun.

She thought of ascending the whole way – making the old pilgrimage, beseeching the high place where the tip of the mountain disappeared into the lower heavens, to send a ship. But what was it, anyway? Only a heap of piled-up rocks, only a mountain. And what could a mountain do? Still, she called the children and followed the path to the First Station. Seven times they shambled around the cairn of stones intoning seven Our Fathers, seven Hail Marys and one Creed. She wondered why once of everything wasn’t enough, why it had to be seven times.

Then she turned her back on St Patrick’s mountain, angry, yet disquieted by her rejection of it, and dragged them down the miles with her to Westport. Westport, relic of the anglicization of Ireland. A Plantation town of well-mannered malls, the canalized Carrowbeg outpouring the grief and suffering of its hapless inhabitants.

St Patrick and the Protestant Planters could have it between them.

5 (#ulink_1142bc12-8a47-5d4d-a8c2-273f3335d650)

Whether her anger had moved the sullen mountain, or whether it was merely favourable winds, the next morning produced a miracle. A ship out of Londonderry – the Jeanie Goodnight – had rounded Achill Island under cover of darkness and now sat at the quay: and she was Boston-bound. Word of the ship’s arrival had spread like wildfire, igniting all of Westport into frenzied quay-life once again. The Inn emptied.

Ellen left the children behind her in the room, admonishing them not to leave it. Wild with excitement, she threw off her shoes and ran bare-stockinged all the way to the office of Mr John Reid, Jun., the dress hiked up behind her like a billowing sail and with every stride storming Heaven that she wasn’t too late.

The quay was teeming with people. Would-be travellers clutched carpetbags to their breasts – food and their entire earthly possessions within. Many were young, single women, who vied for ground with barking agents and anxious excise men. While late-arriving jobbers had their own solution, jabbing at obstructive buttocks with their knob-handled cattle-sticks.

Already the ship agent’s door was mobbed, cries of ‘Amerikay!’ ascending at every turn. Call the damned at the Gates of Hell. Like it was their last hope.

It was her last hope. If they didn’t embark on this ship, who knew when another would come. She and her children would be fated to stay in Ireland. Her money would run out, and in time they would sink lower and lower, until they, too, ended up on scraps of pity and charity and the off-cuts of ass-meat. She lunged into the crowd, all thought of her gender put aside. Nor did the opposite gender give ground to her, unless she took it. Pushing and elbowing, she scrimmaged her way forward until she reached the front.

‘Mr Reid! Mr Reid!’ she shouted, money in her fist, shaking it above her head. ‘Passage for four to Boston!’ she beseeched.

At last he beckoned her forward, she banged down the money onto his desk.

Fifteen minutes later she left, four sailing tickets to Boston clenched like a prayer between her two hands.

Their passage was secured.

The children were overjoyed, Mary more restrained than the others, at the thought of leaving Katie behind. Ellen wondered if the silent girl really understood what all the excitement was about. Sometimes, you just didn’t know with her. But the girl clapped her hands, looking from one to the other of them, her hazel-brown eyes shining, her pert little nose twitching with delight.

Thrice daily, morning, noon, and at eventide, Ellen went to check on the Jeanie Goodnight lest the ship slip out again unexpectedly, just as she had ghosted into the western seaboard town.

Three days later they were headed out into the bay, Westport behind them in the mist, like a shaken shroud. She hated the place. Its workhouse which had taken Michael; the hordes of its hungry, clawing to get aboard the ship ahead of her, the lucky ones, their passage paid by land-clearing landlords.

Once aboard, she had changed her clothes, shaking the stench of Ireland out of them, then boiled them. As the Jeanie Goodnight threaded its way through the drumlin-humped islands, she was aware of the Reek to her left, the cursed mountain always looking down on them, whichever way you went, by land or by sea; watching, judging. She wouldn’t look at it directly. It was part of the Ireland of the past drawing away behind them. An Ireland of Famine; of vacant faces and outstretched hands – an island of beggars, no place for her and her children.

There they had been, she, Michael, all of them, back there in the mountains, waiting, year in year out, for the potatoes to grow. Beating their way down the road to the priest to give thanks, prostrating themselves, when they did grow; beating their breasts in contrition for imagined sins when they didn’t. Then, trudging over and back to Pakenham’s place to pay the rent, hoping he wouldn’t raise it on them when they had it, grovelling for clemency, citing ‘the better times to come’ when they hadn’t.

Always on their knees, giving thanks or pleading. They were to be pitied, the whole hopeless lot of them. It wasn’t the mountains of Maamtrasna that imprisoned them, or the watery arms of the Mask that landlocked them. It wasn’t even, she knew, the landlords and the priests. It was themselves. Going round in circles, beholden to the present and beholden to the past, with its old seafóideach customs, handed down from generation to generation. Tradition, woven around their lives from before they were born, like some giant web. She wanted to strip it all away from her now, never return. If it wasn’t for Michael and Katie back there on its bare-acred mountain, in its useless soil.

‘A Mhamaí …’ The tug at her sleeve startled her.

It was Mary. The child’s eyes, though dry, were blotched from rubbing. Mary would try to hide it from her that she still cried over Katie. That was her way. In the days they had waited for the ship, Ellen had talked to her and Patrick about the need to be strong; the child now beside her looked anything but. Though her first instinct was to take Mary in her arms, Ellen instead led her to the bow of the ship.

‘See, Mary! See out there beyond the horizon – the place where the sea meets the sky?’

Mary nodded.

‘Well, out there is America

‘Is it like Ireland?’ Mary interrupted.

‘No, Mary, it isn’t. America is a big and rich country not like Ireland at all.’

Mary fell silent. Ellen, sensing the child’s disappointment, pressed on. ‘It will be better than Ireland, Mary, I promise you it will be better. But we are going to have to be Americans. We must forget we are Irish. Leave all … all that behind us.’

Mary turned from looking out ahead, trying to see this land where they would be different people. ‘But, a Mhamaí –’

Ellen stopped her, gently. ‘Mary … you mustn’t call me that – “ a Mhamaí ” – any more. We are going to be Americans now. People don’t say that in America. From now on you must call me “Mother”!’

The child said nothing – only looked at her.

‘It’s all right,’ Ellen said, taking her by the shoulders. ‘Nothing’s changed. We’re still the same between us in English as in Irish,’ she smiled. ‘Do you understand?’

Mary once more looked out between the deepening sky and the widening ocean, trying to see beyond where they met. Out to this place, this America.

‘Yes … Mother,’ she answered, giving voice to the strange-sounding word – the wind from America holding it back in her throat, so that Ellen could scarcely catch it.

Out they tacked, past the Clare Island lighthouse, tall and solid-walled. Its white-painted watchtower, lofted heavenwards two hundred feet, would see them safely past Achill Sound. ‘A graveyard for ships,’ Lavelle had told her before she had left Boston. It was his place, Achill. This island, cut off from Ireland’s most westerly shore. ‘Achill – wanting to be in America,’ he always joked.

She hadn’t yet broached the subject of Lavelle with the children, except in a general fashion, like she had mentioned Peabody; both as people in Boston with whom she conducted business dealings. She would have to tell them more about Lavelle – that they were partners, but in business matters only. Albeit that she was fully conscious of his affection for her, and in turn regarded him highly, it was her intention never to remarry. She would be true to Michael to the grave. If, thereby, she was denying herself the tender comforts of marriage life, and a father’s guiding hand for her children, then so be it. That was the price to be paid of her troth to Michael.

An eddy of breeze swirling up from Achill Sound made her shiver slightly. She loosened then re-knotted the blue-green scarf Lavelle had given her at Christmas. She had four long weeks at sea in which to reaffirm her intentions.

The Jeanie Goodnight, a triple-masted emigrant barque, with burthen eight hundred tons, and a master and crew of nineteen, was constructed of the best oak and pine Canadian woods could yield. On her arrival at Westport she had disgorged four hundred tons of Indian corn, twelve hundred bags of the dreaded yellow meal; flour, Canadian timber and East Coast American potatoes. There had been a riot, the poor seeking to seize what supplies arrived with the ship. It was the only way they would get food, by taking it.

When Patrick raised the question of inferior food being shipped into the country crossing with superior food being shipped out, all she could say was, ‘It doesn’t make any more sense to me, Patrick, than it does to you. I don’t understand these things.’ It really didn’t matter what food there was, good or bad. The famished had scarcely a penny between them with which to buy it anyway.

Soon they had sailed beyond the reach of Achill Sound, leaving behind her last view of Ireland – disused lazy beds climbing towards the sky over Clew Bay.

The voyage was a good one, the elements favouring them so that the copper-fastened Jeanie Goodnight sat steady and proud in Atlantic waters. Ellen kept themselves to themselves. Their fellow passengers were a mixed lot. Above deck were the commercial Catholic classes – shopkeepers, grocers, middlemen – and those called ‘strong farmers’, taking what possessions they had, fleeing the sinking ship that was Ireland. There was too a good sprinkling of voyagers from Londonderry and the northern counties.

It surprised her to hear these talk in their brittle way of ‘the calamity biting deep in Ulster’. She found it hard to reconcile the notion that those who called on the Hand of Providence to strike down the ‘lazy Irish Catholics’, should also be stricken by the same levelling Hand.

‘Planters’, or ‘Scots Irish’, as Lavelle called them; Irish, but not Irish. And they were different. More sober in dress and demeanour than the boisterous middlemen from the southern counties. Two hundred years previously, they had been brought in from the Scottish lowlands, and given Catholic land. In return, they were to ‘reform’ Ireland and the Irish. This zeal had never left them. She had seen them in Boston. Hard work and privilege had kept them where they were – looking down on the ‘other’ Irish, every bit as much as the ‘other’ Irish – her Irish – despised them.

These Scots Irish on board the Jeanie Goodnight already spoke of Boston as if it were theirs, naming out to each other the congregations where they would gather to worship; giving no sense that they were leaving anywhere, only of arriving somewhere else.

Below deck, sober demeanour counted for nothing. Nightly the scratch of fiddles and the thud of reel-sets staccatoed the timbers, as the peasant Irish ceilidhed their way to ‘Amerikay’.

The ‘cleared’, passage-paid by landlords happy to see the back of them, at first rejoiced openly at their leaving. Then, inhabitors of neither shore, they floundered in a mid-ocean of conflicting emotions, fuelled by dangerous grog and the more dangerous fiddle music.

Along with the ‘cleared’ a large body of those below deck were single women from sixteen to thirty years, those Ellen had noticed at the quayside. ‘Erin’s daughters’, fleeing Famine and repression. Most would find their way into the homes of affluent Boston as domestic servants to become ‘Bridgets’. Others would sit behind the wheels of the new-fangled sewing machines in the flourishing clothing and cordwaining shops of the Bay Colony. Others still would become ‘mill girls’, in the Massachusetts mill towns of Lawrence and Lowell. There, their fresh young bodies would make the machines sing and the bosses happy, their spirits thirsting for the fields of home and a cooling valley breeze.

In Boston, the agents of those same factory bosses would be waiting on the piers, to corral the fittest and strongest of these young women, to put shoes on the feet of America, clothes on American backs. She had seen it so many times on the Long Wharf when the ships came in.

And she had seen the jaded ‘Bridgets’ traipse down to Boston Common with their silver-spoon charges, glad of an outing and a few mouthfuls of fresh air. And the threadbare needlewomen, bodies like ‘S’ hooks from fifteen hours a day, every day, shaped over their machines.

America indeed promised much. But it took much in return.

Each evening those below were allowed on deck for an hour to cook what little they had on the open stove before being driven below again. Once uncaged, they tore at their carpetbags like ravenous dogs, until the meagre contents contained within, spilled over the timbers. A few praties, a bag of the hard yellow meal – ‘Peel’s Brimstone’, after the British Prime Minister who sought to feed the starving Irish with it, until it sat like marbles, pyramided in their bellies. Sometimes she saw a side of pig or the hindquarter of an ass, smoked or salted for preservation. Finally, the carpetbags carried a drop of castor oil for the bowels – to clear out Peel’s yellow marbles.

Once, horrified, she watched as a young lad, no older than Patrick, was flung from the carpetbag mêlée by a much older man, his father. The boy careered against the tripod supporting the cooking cauldron. But his screams, as his arms and upper body were scalded, served to distract none but his mother from the frenzy taking place. Ellen ran to summon the ship’s doctor but the boy’s frailty was unable to sustain his sufferings and he expired before relief could be administered.

She noticed, the following evening, that the tragedy stayed no hand from the continuing brawls for carpetbag rations.

Again, Ellen kept the children close to her, having found the silent girl one evening to have disappeared and crept amongst the carpetbaggers, peering into their faces, searching out a spark of recognition between any and herself. Ellen could still get nothing from her, nor did the girl speak to either Mary or Patrick.

At first the strangeness of being on the ship had seemed to frighten the girl – as it did Ellen’s own two children. Then, she became fascinated by it. Looking out on every side, running quickly from windward to leeward, watching the land slide away behind them. Or, facing mizzenward, almost, it seemed to Ellen, listening to the flap of the wind in the masts. Other times she would find the girl staring for hours into the deep, ever-changing waters, finding some kinship there, amidst the white spume, the dark silent depths. What was ever to become of her, Ellen wondered. She would have to give her a name. She couldn’t be just the ‘silent girl’, for ever.

The thirty days at sea, whilst giving Ellen time to regain herself, had done nothing to restore her with regard to Patrick.

He still resented her for deserting them and didn’t seek much to conceal it either. Ellen had decided to let things take their own course between them, not to rush him. But Boston wasn’t far away – and Lavelle. If Patrick didn’t show some sign in the next week or so of coming around, then she would have to sit him down anyway and tell him about Lavelle. Already, when she had returned to Ireland to retrieve the children, her changed appearance and failure to return sooner had caused Patrick to accuse her of having a ‘fancy man’ in America.

6 (#ulink_0e991fdb-32e7-5dab-a161-6e791657a5a9)

Three days out of Boston, she spoke to them of Lavelle. ‘I want to tell you about Boston …’ she began. ‘There are a lot of houses. Big, big houses and a lot of streets. Not like our little street in the village, but long, long streets and every one of them crowded with people,’ she explained.

‘Like Westport?’ Mary ventured.

‘Like twenty Westports all pulled together,’ she answered, ‘and the sea on one side of Boston and the rest of America on its other side.’

Mary’s eyes opened wide at the idea. Patrick stayed silent.

‘And Boston Common, itself as big as all Maamtrasna. Where people walk and children play in the Frog Pond and skate in the snow. And,’ she drew in close to them, ‘a giant tree where they used to hang witches! And,’ she moved on, seeing the frightened look on Mary’s face, ‘horses that pull tram carts – you’ll love going in them.’

‘When we get there you’ll be going to school to learn all about Boston and America, and lots of other things besides,’ she went on, wondering what she would do for the silent girl in this regard.

‘Will you not be doing the Lessons with us any more, a –’ Mary started to ask and corrected herself, ‘Mother?’

‘Well, Mary, I think you and Patrick are too grown up for me to be still teaching you at home. The best schools in the whole, wide world are in Boston. It will be very exciting for you both with American children … English and German children … children from everywhere,’ she told them.

‘Will they be like us?’ Patrick spoke for the first time.

Ellen, not sure of what he meant, replied, ‘Yes, of course they will. They’ll all be of an age with yourselves, bright and eager to get on,’ she said, thinking she had answered him.

‘No, but like us – Irish?’ he countered.

She had to think for a minute. ‘Yes, yes, of course there will be children like you, who have come from Ireland. Did I not say that?’

Patrick pressed his point. ‘And what about those?’ he pointed to the deckfloor, ‘those below there?’

‘Well I’m sure they’ll all be wanting education,’ she half-answered. The way Patrick looked at her told her he knew she had tried to skirt his question. She decided to plunge straight on, into the deeper end of things. ‘Now, as well as the schools, you’ll meet some people in Boston … who – who have helped me …’ She slowed, picking out the words. ‘A Mr Peabody, a merchant who owns shops …’

Patrick watched her intently, searching out any flicker or falter that would betray her.

‘Mr Peabody helped me to get started in business and a Mr Lavelle, a friend …’ she could feel Patrick’s eyes burning into her, ‘… who saved my life and helped me escape Australia to get back to you. Mr Lavelle works with me in the business.’

There, she had gotten it all out and in one blurt. It was so silly of her to be nervous of telling them, her own children.

Neither of them had any questions, Mary’s face lighting up at the news that Mr Lavelle had saved her mother’s life.

‘Oh, he must be a good man, this Mr Lavelle, to do that … a good man like Daddy was!’ she added.

‘He is,’ Ellen said, more shaken by the innocence of Mary’s statement than by any hard question Patrick might have asked. It was what she had wanted to avoid at all costs – any notion that Lavelle was stepping into their father’s shoes. He wasn’t. God knows, he wasn’t.

Soon they were within sight of America, evidenced by increased activity in every quarter of the Jeanie Goodnight. Ellen still had not resolved the problem of naming the silent girl. Calling her by no name seemed to be so soulless. How well she had come on since Ellen had first found her. Or rather since the girl had first found them, on the road towards Louisburgh. Now, if only she’d speak – tell them what her name was. Ellen determined to try again with her.

To her horror she found the girl part way up the rigging, seeking a better view of America. Petrified that she’d fall, Ellen anxiously beckoned for her to come down.

The girl jumped on to the deck, smiling at Ellen. Tall and dark-haired, her frame now filled out the skimpy dress that, a month past, had hung so shapelessly on her. Still looked scrawny but at least she was on the way.

‘What’s your name, child, and where did you come from?’ Ellen asked. The girl, eyes still alight with the rigging fun, just looked back at her – happy, forlorn, smiling, such a mixture, Ellen thought. She must have her own pinings and no one to share them with.

The one and only time the girl had spoken, at Katie’s burial, it had been in Irish. She probably had no English. Ellen tried again asking her name, this time in Irish. English or Irish, the silent girl made no response. Ellen was sure the girl heard her, understood her even, but, for whatever reason, could not, or would not, reply.

‘We have to get you a name, child,’ she said, touching the girl’s face. ‘A name to go with those hazel-brown eyes and that pert little nose of yours. A name for America.’

The deck was now getting crowded with sea-weary travellers, jubilant at the sight of land before them. Before she could progress things further with the girl, Mary ran at her all of a tizzy.

‘Is that it, is that Boston?’ she burst out, more like Katie than anything, unable to hold back the excitement the sight before them evoked. Patrick too arrived, his forehead dark and intense with interest, but not wanting them to see it.

Ellen felt her own spirits quicken. Momentarily forgetting her quest for a name, she began pointing out places to them. ‘Look at all the ships! Remember, I told you. And all the islands, let’s see if I still have names for them?’

Mary laughed at the strange-sounding names as Ellen tried to get them right.

‘Noodles Island, Spectacles Island, Apple Island and Pudding Point!’ she rattled off, pleased with herself.

‘No shortage of food here in America then,’ Patrick cut in, trying to deny them the moment.

Ellen ignored him. ‘And that’s Deer Island! We’ll have to stop there for … for the people below, for quarantine … that they have no diseases,’ she hurried to explain.

And their eyes were agape at the size and splendour of America, with its tall spires distantly spiking the heavens.

‘There’s the harbour way ahead,’ she pointed out, trying to distinguish the Long Wharf, ‘where we’ll dock. Beyond that is the State House and Quincy Market.’ They heard the quiver of recognition in her voice as she tumbled out the names, all foreign, all strange to them. ‘Further up is Boston Common – I’ll take you there.’ She hugged the three of them, this time leaving out the witches. ‘On the higher ground at the back – you can’t see it clearly from this far – is Beacon Hill, where once were lit the warning lights for the city if it was going to be attacked.’ She gabbled on, childlike, dispensing all she knew to them. ‘And there’s a place up there called Louisburgh Square – like Louisburgh back home – where we found –’ She stopped, looking at the silent girl in front of her. ‘Louisburgh – that’s it! That’s it!’ She laughed excitedly. ‘We’ll call her after the place where she was found, and the place she is coming to! Louisburgh – we’ll call her “Louisa”.’

Ellen looked from one to the other of them. Mary smiled, nodding her head up and down. Patrick signalled neither assent nor dissent. ‘“Louisa” – it’s a good name, a grand name,’ Ellen went on. How easy it had been in the end – naming the girl. ‘It’ll suit her well! Oh, everything is working out fine! I knew it would once we came to America!’

The silent girl, who had drifted a few paces off from them, sensing the commotion turned from looking at her new home, the place she was now being named for.

‘Louisa!’ Ellen took the girl by the arms, dancing them up and down with delight – like a girl herself. ‘Louisa – welcome to America!’

The girl just looked at her, before turning her attention back to the sight of her adopted home, indifferent in the extreme to her new appellation.

‘It’s not even an Irish name,’ Patrick mumbled, more to himself than anybody.

Ellen, nevertheless, heard him. ‘You’re right, Patrick … it’s not,’ she said sharply, fed up with his surliness.

‘It’s American!’

7 (#ulink_bdfe034c-8e14-558a-b2be-e91dbf6c09c0)

Lavelle was waiting on the Long Wharf for them. As they disembarked he waved, a big smile creasing his weathered face. It was easy to pick him out on the thronged jetty, his well-built frame setting him apart as much as the casual colours he favoured – a russet-coloured jacket; a wheaten homespun shirt – colours of the season. But he wouldn’t have thought of that, she knew, watching the bob of his head – like summer corn in the autumn sun. He never looked Irish, the way Michael did – ‘Black Irish’ with the Spanish blood. Lavelle always looked Australian, reminding her of the bushland, the baked earth, the wide-open spaces. She was pleased to see him, but nervous, none the less, about how the children might regard him. Of her own reaction to him she was clear. He was her business partner, her good companion. She would reinstate that particular relationship from today and that relationship only.

He was restrained when he moved to greet them through the milling crowds, but shook her hand warmly.

‘Ellen, it’s good to see you again! You’re welcome back! And who are these fine young ladies and gentleman?’ he went on, unsure of how to deal with her return.

She saw him stop for a moment as he took in Mary, looked for the missing Katie, then at Louisa, it not making sense to him.

‘This is Patrick,’ she intervened. ‘Patrick, this is Mr Lavelle of whom I spoke … and this is Mary,’ Ellen introduced the nine-year-old image of herself. ‘And this is …’ she paused as Lavelle’s gaze transferred to the silent girl, ‘… this is Louisa, who has come with us to Boston.’ She saw the question still remain in his eyes. ‘We had to leave Katie behind … with Michael.’

He caught her arm, understanding at once. ‘Oh, I’m sorry, Ellen. So sorry – you’ve had so much of trouble … after everything else to …’ he faltered, unable to find the words.

‘Well, we’re here,’ she said simply. ‘At last, we’re here.’

‘And how is it in Ireland?’ Lavelle moved on the conversation.

They would talk later of Katie and this girl Louisa who, when he made to greet her, seemed not to notice. him. She was deficient of hearing, or speech, or both, he thought.

‘Ireland is poorly,’ Ellen answered him, ‘Ireland is lost entirely.’

‘And what of the Insurrection – the Young Irelanders – we read something of it in the Pilot?’ he said, referring to the Archdiocese of Boston’s weekly newspaper.

‘The Insurrection failed – I brought you some newspapers, The Nation,’ she answered. ‘There was much talk of it in Ireland and aboard ship. I have little interest in it. Now we are here and Ireland is …’ she turned her head seawards, ‘… there.’

He heard the weariness in her voice. God only knows what she had gone through to redeem her two remaining children.

‘Mr Peabody enquires after you frequently,’ he said, in an effort to brighten her up, knowing how much she enjoyed her dealings with the Jewish merchant.

‘Oh! And is he well himself, and the business – how is it?’ she asked.

‘Both Mr Peabody and the business continue to thrive,’ he told her with a certain amount of satisfaction, she noticed. Things must have gone better between him and Peabody, in her absence, than she had hoped for.

The children were agog at Boston’s Long Wharf, stretching, as Mary put it, ‘from the middle of the sea, to the middle of the town’.

‘City,’ corrected Patrick, showing he was a man of the world, not like his sister who knew nothing. ‘It’s a city!’

If Westport Quay swirled with all the varied elements of quayside life, then here, in Boston, it was as if the mixed ingredients of the whole world had collided together. Tea-ships, ice-ships, spice-ships. Syphilitic sailors, back from the South Seas, poxed and partially blind, bringing home with them ‘the ladies’ fever’ and the stale stench of flensed whales. In their midst stood sinless and sober-suited Bostonians cut from the finest old Puritan stock; anxious for merchandise, disgusted by this new influx of paupers and the sanitary evils accompanying them.

The hiring agents of the mill bosses sized up this fresh supply of factory fodder. ‘Labour!’ they hollered, to the sea of ‘green hands’. ‘Labour!’ they called, winking and smiling at the wide-eyed Irish girls. Seeking to seduce with smiles, as much as with dollars, those they considered ‘sober of habit, sound of limb and with good strong backs’ – as they had been instructed. One man’s ‘sanitary evil’, it seemed in America, was another’s ‘strong back’.

The children’s heads turned at every step, gawking at this and that, each new sight and sound of Boston a greater wonder to them than the one before. Like the gaudily bedecked sailors of various hue, reeking of spices and perfumes from the far reaches of the Orient, chattering in unintelligible tongues. Or a few freed slaves from the South silently bullocking the heavy cargo. She had to prevent them from staring.

‘But that man … he’s all black, what happened to him?’ Mary couldn’t contain herself.

‘He’s a Negro – from Africa,’ Ellen hushed her.

‘But will it rub off?’ Mary persisted.

‘Only if you shake hands with him, Mary,’ Lavelle cut in solemnly.

Mary’s eyes opened even wider, craning her neck to see this man who would change colour at a touch.

‘Mr Lavelle should have more sense, Mary, ignore him!’ Ellen rejoined. ‘Some people have a different skin to ours, that’s all – and it doesn’t rub off!’ she stated emphatically, more to Lavelle than to Mary. Nothing she had told them about America had ever prepared them for this, for Boston’s Long Wharf.

And the Irish. Everywhere the Irish; shouting, laughing, crying, mobbed by relatives who had crossed the Atlantic before them. Others, solitary young girls clinging to their carpetbags – no one to meet them in this throbbing kaleidoscope, this frightening place. Like motherless calf-whales they were, these daughters of Erin floundering unprotected in the great ocean of America. Easy prey to the welcoming smile, the outstretched hand, the familiar lilt; to their own, the Irish crimpers and ‘harpies’, who would flense them of everything.

‘I can see that Boston is as busy and bustling as ever,’ she said to Lavelle, full of being back in the place.

‘And bursting at the seams – thousands have arrived these past months – mostly Irish,’ he replied. ‘The bosses are happy; “green hands” from Ireland mean cheap labour,’ he continued, ‘but the City Fathers are not, thinking pauperism and Popery both will sink Boston!’

She didn’t care much about either bosses or Brahmins. Boston, bursting or not, was such a far cry from what she had left; the tumbled villages, a famished land; silence – no hope. Here there was hope. To her, the city with its crowded chaos, its cacophonous quay-life, rang out with the very music of hope.

‘Stop, Lavelle! Stop here!’ she called out of a sudden, almost forgetting. ‘I want them to see it!’

Lavelle ‘whoaupped’ the big bay mare he had hired for the day and had scarcely pulled them to a halt, when gathering up her skirts she leapt from the trap-cart.

‘Come on, come on!’ she beckoned to the children, shepherding them across the mouth of the busy wharf.

Lavelle stayed where he was. She was as impetuous as ever, he thought, watching the long straight back of her weave through the crowds. He smiled to himself – the factory bosses would be glad of a back like that! Three months since she had left and he had thought about her every day, wondering what awaited her in Ireland. Wondering when, if ever, she would return. Then, these past few weeks, scouring the pages of the Pilot for shipping intelligence and hoping for a fair wind to bring her back.

She looked a bit racked, he thought. Her face, the way she didn’t smile as big as he remembered. The furrow above her lips – the one he could never help watching, fascinated at how its fine fold rose and fell with the cadence of her speech. It didn’t fall and rise so much now, as if she was holding it back, keeping it in check. Still, it was a wonder at all that she looked as well as she did. She must have been too late to save them both, whatever had happened. That must have near killed her, would eat away at her for ever, he knew. This one, Mary, with the dos of wild red hair on her – how like Ellen she looked. Going to be tall like her too. He could see it now, as together they rounded the corner of the building away from him. The girl was quieter, less impetuous, more of a thinker. But maybe that was down to the foreignness of the place and him being present. And all that had happened.

The boy had made strange with him. With his unruly black head and sallow skin, he looked more like he’d come off a ship from the Spanish Americas, than Ireland. He was unlike her in every feature. Lavelle wondered about the boy’s father, her husband. It was her strong attachment to his memory that was holding back her affections. He had been hoping that when she stepped down from the ship, she would be wearing the scarf he had given her. But she wasn’t. He wondered what she had told the children. Or, if she’d thought much on him at all these past three months?

And the girl – the one who said nothing, only taking you in with those big brown eyes. Where had she appeared from? Maybe she was a neighbour’s child, orphaned by famine. Nearly more orphanages than groggeries in Boston too, so fast were they springing up. She’d probably put the girl into one of those – run by the Sisters. He ‘gee’d’ the horse, threading it gingerly after them, glad that he’d painted the sign. It would be a surprise for her. She was standing in front of it, her finger outstretched, reading aloud the strange-sounding words to the children. She turned, hearing the clip-clop of the horse.

‘Mr Lavelle’s been busy painting, I can see,’ she said to them. But it was meant for him, he knew. ‘“The New England Wine Company”,’ she read out the larger letters again, then the smaller ones underneath, ‘“Importers of fine wines, ports and liqueurs”. That’s us!’ she said to them with a little laugh. Even Patrick seemed impressed, looking at her, then at the sign over the warehouse, then back at Lavelle, trying to piece it all together.

‘You’re a merchant, Mother!’ Mary said, flushed with pride in her, yet seeming not in the least bit surprised.

‘I … I suppose I am,’ Ellen replied, never having thought of herself in that way.

They went inside, Louisa remaining close by her, Mary and Patrick going from rack to rack examining the cradled bottles and the labels with the unusual writing wrapped round them.

‘Fron-teen-nyac, pair ay fees’ – Frontignac, Père et Fils – she tried to explain, ‘the people we get the wine from in Canada. Frontignac, Father and Son,’ she went on, watching them watch her as if she was some stranger. And in truth she was. Their memories of her were as far removed from the woman now before them, explaining French wines, as Massachusetts was from the Maamtrasna valley. An ocean in the heart’s geography. It would take time.

‘Bore-dough,’ she pointed to a ruby rich red, ‘the place the wine comes from in France.’

It was a strange thing, Patrick thought, for her to know about, her and the ‘fancy man’ that kept watching him and kept smiling at his mother.

Ellen was well pleased at what she saw. Lavelle had kept the warehouse solidly stocked against the coming season and the winter closing of the St Lawrence river. Furthermore, he had secured her new accommodation.

‘In Washington Street between Milk and Water Streets, near the Old Corner Bookstore,’ he told her. ‘I know you like to be at the centre of things, and it’s bigger, more suitable now with the children.’ She had surrendered her old lodgings, not knowing how long she would be away. Her belongings Lavelle had stored in the warehouse, and more recently moved to the new address, paying the rent to secure it against her return. He himself continued to live where he previously had, in the North End, though it was ‘now being over-run with the poorest of our own’.

The Long Wharf led them into State Street, New England’s financial heart, its temples of commerce close to the city’s importing and exporting lifeline – the wharves. Lavelle took them left at the Old State House, down along Washington Street, its patchwork of buildings, filled with apothecaries, engravers, instrument-makers and ‘Newspaper Row’. Signs and hoardings jutted everywhere, higgledy-piggledy, while canvas awnings over the footwalks provided shelter from the rain, shade from the sun, for those with dollars to spend.

Four flights of stairs they climbed of the high-shouldered building, which itself stretched upwards above the world of commerce below. The effort was repaid in full when arriving in their rooms she saw, across from them on the corner of Milk Street, the nestled campaniles of the Old South Meeting House; how they ascended like a pinnacled prayer to the steepled sky.

She knew she would love it here ‘on top of the world’, as she said to Lavelle. They had three rooms. One large, with two windows, for living in, and above that, two smaller rooms, each lighted by dormers, for sleeping. The larger one for herself and the girls, the smaller for Patrick. She had considered giving the three children the larger one, her taking the lesser room. But Patrick was of an age now.

It was close to everywhere. The Wharf and their warehouse, the Common, shops, churches, schools. The Old Corner Bookstore – which she had commenced frequenting before she left – now only a hen’s footstep away. Beneath their roost, on the next floor down, were commercial offices. Below that again, suppliers of mathematical instruments, while a sewing shop for ladies’ garments and a dye house occupied the street level of the premises.

She was grateful to Lavelle. He had gone to some trouble to find this place, knowing how much she preferred the rattle and hum of city life above the quiet of some numbing suburb. The frantic commercial life of ‘Hub City’, as Bostonians liked to call it, was rapidly devouring all available space here at its centre. She wondered how long it would be before trade and commerce would drive further out the dwindling number of inhabitants, like themselves. Where they now stood would soon enough fall into use as an instrument-maker’s den, or a sewing sweatshop. But while ever they could remain here, she knew she would be happy.