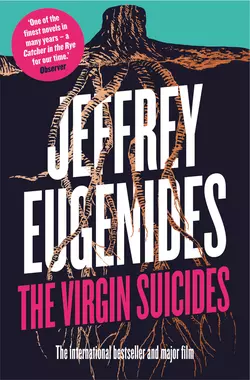

The Virgin Suicides

Jeffrey Eugenides

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 619.22 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: In a quiet suburb of Detroit, the five Lisbon sisters – beautiful, eccentric, and obsessively watched by the neighborhood boys – commit suicide one by one over the course of a single year.As the boys observe them from afar, transfixed, they piece together the mystery of the family’s fatal melancholy, in this hypnotic and unforgettable novel of adolescent love, disquiet, and death.Jeffrey Eugenides evokes the emotions of youth with haunting sensitivity and dark humour and creates a coming-of-age story unlike any of our time. ‘The Virgin Suicides’ was adapted into a critically acclaimed film by Sofia Coppola.