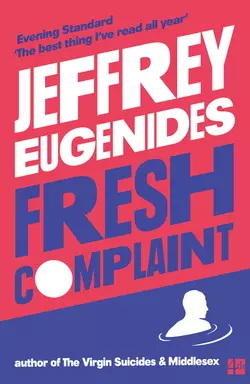

Fresh Complaint

Jeffrey Eugenides

AN OBSERVER BOOK OF THE YEARAN EVENING STANDARD BOOK OF THE YEAR‘What was it about complaining that felt so good? You and your fellow sufferer emerging from a thorough session as if from a spa bath, refreshed and tingling?’The first-ever collection of short stories from Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jeffrey Eugenides presents characters in the midst of personal and national emergencies.We meet Kendall, a failed poet who, envious of other people’s wealth during the real estate bubble, becomes an embezzler; and Mitchell, a lovelorn liberal arts graduate on a search for enlightenment; and Prakrti, a high school student whose wish to escape the strictures of her family leads to a drastic decision that upends the life of a middle-aged academic.Jeffrey Eugenides’s bestselling novels Middlesex, The Virgin Suicides and The Marriage Plot have shown him to be an astute observer of the crises of adolescence, self-discovery and family love. These stories, from one of our greatest authors, explore equally rich and intriguing territory.Narratively compelling and beautifully written, Fresh Complaint shows all of Eugenides’s trademark humour, compassion and complex understanding of what it is to be human.

Copyright (#ulink_a377fc33-3745-5bfc-ba76-89d6012a6bbb)

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk (http://www.4thEstate.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by 4th Estate

First published in the United States by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 2017

Copyright © 2017 by Jeffrey Eugenides

Cover design by Heike Schüssler

Jeffrey Eugenides asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This story collection is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007447886

Ebook Edition © 2017 ISBN: 9780008243821

Version: 2018-08-22

Dedication (#ulink_3b8a7615-b188-5c33-9d82-1a064b5ab623)

In memory of my mother, Wanda Eugenides (1926–2017),

and of my nephew, Brenner Eugenides (1985–2012)

Contents

Cover (#u71c91b2d-f3ed-5dac-a7a6-8fffeb2830e5)

Title Page (#u8ca18324-a6cd-52bd-b027-7fe702bf2dc1)

Copyright (#u004d4ce7-fc04-5859-9f3c-c95a110890c4)

Dedication (#u0bc3b9d4-81c4-52ff-882e-40fbbcecda17)

Complainers (#ue353e574-f4a7-5681-9379-6ad184dcc441)

Air Mail (#u5f691c2c-514d-51eb-9a1a-710aa0ab9630)

Baster (#u7700bc95-aabf-5d30-808c-5438b52536b1)

Early Music (#litres_trial_promo)

Timeshare (#litres_trial_promo)

Find the Bad Guy (#litres_trial_promo)

The Oracular Vulva (#litres_trial_promo)

Capricious Gardens (#litres_trial_promo)

Great Experiment (#litres_trial_promo)

Fresh Complaint (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Jeffrey Eugenides (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

COMPLAINERS (#ulink_81c08f40-8648-5307-9492-4213db2bc1d9)

Coming up the drive in the rental car, Cathy sees the sign and has to laugh. “Wyndham Falls. Gracious Retirement Living.”

Not exactly how Della has described it.

The building comes into view next. The main entrance looks nice enough. It’s big and glassy, with white benches outside and an air of medical orderliness. But the garden apartments set back on the property are small and shabby. Tiny porches, like animal pens. The sense, outside the curtained windows and weather-beaten doors, of lonely lives within.

When she gets out of the car, the air feels ten degrees warmer than it did outside the airport that morning, in Detroit. The January sky is a nearly cloudless blue. No sign of the blizzard Clark’s been warning her about, trying to persuade her to stay home and take care of him. “Why don’t you go next week?” he said. “She’ll keep.”

Cathy’s halfway to the front entrance when she remembers Della’s present and doubles back to the car to get it. Taking it out of her suitcase, she’s pleased once again by her gift-wrapping job. The paper is a thick, pulpy, unbleached kind that counterfeits birch bark. (She had to go to three different stationery stores to find something she liked.) Instead of sticking on a gaudy bow Cathy clipped sprigs from her Christmas tree—which they were about to put at the curb—and fashioned a garland. Now the present looks handmade and organic, like an offering in a Native American ceremony, something given not to a person but to the earth.

What’s inside is completely unoriginal. It’s what Cathy always gives Della: a book.

But it’s more than that this time. A kind of medicine.

Ever since moving down to Connecticut Della has complained that she can’t read anymore. “I just don’t seem to be able to stick with a book lately,” is how she puts it on the phone. She doesn’t say why. They both know why.

One afternoon last August, during Cathy’s yearly visit to Contoocook, where Della was still living at the time, Della mentioned that her doctor had been sending her for tests. It was just after five, the sun falling behind the pine trees. To get away from the paint fumes they were having their margaritas on the screened-in porch.

“What kind of tests?”

“All kinds of stupid tests,” Della said, making a face. “For instance, this therapist she’s been sending me to—she calls herself a therapist but she doesn’t look more than twenty-five—she’ll make me draw hands on clocks. Like I’m back in kindergarten. Or she’ll show me a bunch of pictures and tell me to remember them. But then she’ll start talking about other things, see. Trying to distract me. Then later on she’ll ask what was in the pictures.”

Cathy looked at Della’s face in the shadowy light. At eighty-eight Della is still a lively, pretty woman, her white hair cut in a simple style that reminds Cathy of a powdered wig. She talks to herself sometimes, or stares into space, but no more than anyone who spends so much time alone.

“How did you do?”

“Not too swell.”

The day before, driving back from the hardware store, in nearby Concord, Della had fretted about the shade of paint they chose. Was it bright enough? Maybe they should take it back. It didn’t look as cheerful as it had on the paint sample in the store. Oh, what a waste of money! Finally, Cathy said, “Della, you’re getting anxious again.”

That was all it took. Della’s expression eased as if sprinkled with fairy dust. “I know I am,” she said. “You have to tell me when I get like that.”

On the porch, Cathy sipped her drink and said, “I wouldn’t worry about it, Della. Tests like that would make anybody nervous.”

A few days later Cathy went back to Detroit. She didn’t hear any more about the tests. Then, in September, Della called to say that Dr. Sutton had arranged a house call and had asked Bennett, Della’s oldest son, to be in attendance. “If she wants Bennett to drive on up here,” Della said, “it’s probably bad news.”

The day of the meeting—a Monday—Cathy waited for Della to call. When she finally did, her voice sounded excited, almost giddy. Cathy assumed the doctor had granted her a clean bill of health. But Della didn’t mention the test results. Instead, in a mood of almost delirious happiness, she said, “Dr. Sutton couldn’t get over how cute we’ve got my house looking! I told her what a wreck it was when I moved in, and how you and I have a project every time you visit, and she couldn’t believe it. She thought it was just darling!”

Maybe Della couldn’t face the news, or had already forgotten it. Either way, Cathy felt afraid for her.

It was left for Bennett to get on and tell her the medical details. These he delivered in a dry, matter-of-fact tone. Bennett works for an insurance company, in Hartford, calculating the probabilities of illness and death on a daily basis, and this was maybe the reason. “The doctor says my mom can’t drive anymore. Or use the stove. She’s going to put her on some medicine, supposed to stabilize her. For a while. But, basically, the upshot is she can’t live on her own.”

“I was just out there last month and your mom seemed fine,” Cathy said. “She just gets anxious, that’s all.”

There was a pause before Bennett said, “Yeah, well. Anxiety’s part of the whole deal.”

What could Cathy do from her position? She was not only out in the Midwest but a kind of oddity or interloper in Della’s life. Cathy and Della have known each other for forty years. They met when they both worked at the College of Nursing. Cathy was thirty at the time, recently divorced. She’d moved back in with her parents so that her mother could look after Mike and John while she was at work. Della was in her fifties, a suburban mother who lived in a fancy house near the lake. She’d gone back to work not because she was desperate for money—like Cathy—but because she had nothing to do. Her two oldest boys had already left home. The youngest, Robbie, was in high school.

Normally they wouldn’t have come in contact at the college. Cathy worked downstairs, in the bursar’s office, while Della was the executive secretary to the dean. But one day in the cafeteria Cathy overheard Della talking about Weight Watchers, raving about how easy the program was to stick to, how you didn’t have to starve.

Cathy had just begun to date again. Another way of putting it was she was sleeping around. In the wake of her divorce she’d been seized by a desperation to make up for lost time. She was as reckless as a teenager, doing it with men she barely knew, in the backseats of cars, or on the floors of carpeted vans, while parked on city streets outside houses where good Christian families lay peacefully sleeping. In addition to the sporadic pleasures she took from these men, Cathy was seeking some kind of self-correction, as if the men’s butting and thrusting might knock some sense into her, enough to keep her from marrying anyone like her ex-husband ever again.

Coming home after midnight from one of these encounters, Cathy took a shower. After getting out, she stood before the bathroom mirror, appraising herself with the same objective eye she later brought to renovating houses. What could be fixed? What camouflaged? What did you have to live with and ignore?

She started going to Weight Watchers. Della drove her to the meetings. Small and pert, with frosted hair, large glasses with translucent pinkish frames, and a shiny rayon blouse, Della sat on a pillow to see over the wheel of her Cadillac. She wore corny pins in the shape of bumblebees or dachshunds, and drenched herself in perfume. It was some department-store brand, floral and cloying, engineered to mask a woman’s natural smell rather than accentuate it like the body oils Cathy dabbed on her pressure points. She pictured Della spritzing perfume from an atomizer and then prancing around in the mist.

After they’d both lost a few pounds, they splurged, once a week, on drinks and dinner. Della brought her calorie counter in her purse to make sure they didn’t go too wild. That was how they discovered margaritas. “Hey, you know what’s lo-cal?” Della said. “Tequila. Only eighty-five calories an ounce.” They tried not to think about the sugar in the mix.

Della was only five years younger than Cathy’s mom. They shared many opinions about sex and marriage, but it was easier to listen to these outdated edicts coming from the mouth of someone who didn’t presume ownership over your body. Also, the ways Della differed from Cathy’s mother made it clear that her mom wasn’t the moral arbiter she’d always been in Cathy’s head, but just a personality.

It turned out that Cathy and Della had a lot in common. They both liked crafts: decoupage, basket weaving, antiquing—whatever. And they loved to read. They lent library books to each other and after a while took out the same books so they could read and discuss them simultaneously. They didn’t consider themselves intellectuals but they knew good writing from bad. Most of all, they liked a good story. They remembered the plots of books more often than their titles or authors.

Cathy avoided going to Della’s house, in Grosse Pointe. She didn’t want to subject herself to the shag carpeting or pastel drapes, or run into Della’s Republican husband. She never invited Della over to her parents’ house, either. It was better if they met on neutral ground, where no one could remind them of their incongruity.

One night, two years after they met, Cathy took Della to a party some women friends were having. One of them had attended a talk by Krishnamurti, and everyone sat on the floor, on throw pillows, listening to her report. A joint started going around.

Uh-oh, Cathy thought, when it reached Della. But to her surprise Della inhaled, and passed the joint on.

“Well, if that doesn’t beat all,” Della said, afterward. “Now you got me smoking pot.”

“Sorry,” Cathy said, laughing. “But—did you get a buzz?”

“No, I did not. And I’m glad I didn’t. If Dick knew I was smoking marijuana, he’d hit the roof.”

She was smiling, though. Happy to have a secret.

They had others. A few years after Cathy married Clark, she got fed up and moved out. Checked into a motel, on Eight Mile. “If Clark calls, don’t tell him where I am,” she told Della. And Della didn’t. She just brought Cathy food every night for a week and listened to her rail until she got it out of her system. Enough, at least, to reconcile.

“A present? For me?”

Della, still full of girlish excitement, gazes wide-eyed at the package Cathy holds out to her. She is sitting in a blue armchair by the window, the only chair, in fact, in the small, cluttered studio apartment. Cathy is perched awkwardly on the nearby daybed. The room is dim because the venetian blinds are down.

“It’s a surprise,” Cathy says, forcing a smile.

She’d been under the impression, from Bennett, that Wyndham Falls was an assisted-living facility. The website makes mention of “emergency services” and “visiting angels.” But from the brochure Cathy picked up in the lobby, on her way in, she sees that Wyndham advertises itself as a “55+ retirement community.” In addition to the many elderly tenants who negotiate the corridors behind aluminum walkers, there are younger war veterans, with beards, vests, and caps, scooting around in electric wheelchairs. There’s no nursing staff. It’s cheaper than assisted living and the benefits are minimal: prepared meals in the dining room, linen service once a week. That’s it.

As for Della, she appears unchanged from the last time Cathy saw her, in August. In preparation for the visit she has put on a clean denim jumper and a yellow top, and applied lipstick and makeup in the right places and amounts. The only difference is that Della uses a walker herself now. A week after she moved in, she slipped and hit her head on the pavement outside the entrance. Knocked out cold. When she came to, a big, handsome paramedic with blue eyes was staring down at her. Della gazed up at him and asked, “Did I die and go to heaven?”

At the hospital, they gave Della an MRI to check for bleeding in the brain. Then a young doctor came in to examine her for other injuries. “So there I am,” Della told Cathy over the phone. “Eighty-eight years old and this young doctor is checking over every inch of me. And I mean every inch. I told him, ‘I don’t know how much they’re paying you, but it isn’t enough.’”

These displays of humor confirm what Cathy has felt all along, that a lot of Della’s mental confusion is emotional in origin. Doctors love to hand out diagnoses and pills without paying attention to the human person right in front of them.

As for Della, she has never named her diagnosis. Instead she calls it “my malady,” or “this thing I’ve got.” One time she said, “I can never remember the name for what it is I have. It’s that thing you get when you’re old. That thing you most don’t want to have. That’s what I’ve got.”

Another time she said, “It’s not Alzheimer’s but the next one down.”

Cathy isn’t surprised that Della represses the terminology. Dementia isn’t a nice word. It sounds violent, invasive, like having a demon scooping out pieces of your brain, which, in fact, is just what it is.

Now she looks at Della’s walker in the corner, a hideous magenta contraption with a black leatherette seat. Boxes protrude from under the daybed. There are dishes piled in the sink of the tiny efficiency kitchen. Nothing drastic. But Della has always kept the tidiest of houses, and the disarray is troubling.

Cathy’s glad she brought the present.

“Aren’t you going to open it?” she asks.

Della looks down at the gift as though it has just materialized in her hands. “Oh, right.” She turns the package over. Examines its underside. Her smile is uncertain. It’s as though she knows that smiling is required at this moment but isn’t sure why.

“Look at this gift-wrapping!” she says, finally. “It’s just precious. I’m going to be careful not to tear it. Maybe I can reuse it.”

“You can tear it. I don’t mind.”

“No, no,” Della insists. “I want to save this nice paper.”

Her old spotted hands work at the wrapping paper until it comes unstuck. The book falls into her lap.

No recognition.

That doesn’t mean anything, necessarily. The publishers have put out a new edition. The original cover, with the illustration of the two women sitting cross-legged in a wigwam, has been replaced by a color photograph of snowcapped mountains, and jazzier type.

A second later, Della exclaims, “Oh, hey! Our favorite!”

“Not only that,” Cathy says, pointing at the cover. “Look. ‘Twentieth-Anniversary Edition! Two Million Sold!’ Can you believe it?”

“Well, we always knew it was a good book.”

“We sure did. People should listen to us.” In a softer voice Cathy says, “I thought it might get you back to reading, Della. Since you know it so well.”

“Hey, right. Sort of prime the pump. The last book you sent me, that Room? I’ve been reading that for two months now and haven’t gotten further than twenty pages.”

“That book’s a little intense.”

“It’s all about someone stuck in a room! Hits a little close to home.”

Cathy laughs. But Della isn’t entirely joking and this gives Cathy an opportunity. Sliding off the daybed, she gesticulates at the walls, groaning, “Couldn’t Bennett and Robbie get you a better place than this?”

“They probably could,” Della says. “But they say they can’t. Robbie’s got alimony and child support. And as far as Bennett goes, that Joanne probably doesn’t want him spending any money on me. She never liked me.”

Cathy sticks her head in the bathroom. It’s not as bad as she expects, nothing dirty or embarrassing. But the rubberized shower curtain looks like something in an asylum. That’s something they can fix right away.

“I’ve got an idea.” Cathy turns back to Della. “Did you bring your family photos?”

“I sure did. I told Bennett I wasn’t going anywhere without my photo albums. As it is, he made me leave all my good furniture behind, so the house will sell. But do you know what? So far not a single person has even come through.”

If Cathy is listening, she doesn’t show it. She goes to the window and yanks up the blinds. “We can start by brightening things up a little in here. Get some pictures on the walls. Make this place look like somewhere you live.”

“That would be good. If this place wasn’t so pitiful-looking, I think I might feel better about being here. It’s almost like being—incarcerated.” Della shakes her head. “Some of the people in this place are sort of on the edge, too.”

“They’re edgy, huh?”

“Real edgy,” Della says, laughing. “You have to be careful who you sit next to at lunch.”

After Cathy leaves, Della watches the parking lot from her chair. Clouds are massing in the distance. Cathy said the storm won’t get here until Monday, after she’s gone, but Della, feeling apprehensive, reaches for the remote.

She points it at the TV and presses the button. Nothing happens. “This new TV Bennett got me isn’t worth a toot,” she says, as though Cathy, or someone, is still there to listen. “You have to turn on the TV and then this other box underneath. But even when I manage to get the darn TV on, I can never find any of my good shows.”

She has put down the remote just as Cathy emerges from the building, on the way to her car. Della follows her progress with perplexed fascination. Part of why she discouraged Cathy from coming out now wasn’t about the weather. It’s that Della isn’t sure she’s up to this visit. Since her fall and the hospital stay, she hasn’t felt too good. Sort of punky. Going around with Cathy, getting caught up in a whirlwind of activity, might be more than she can handle.

On the other hand, it would be nice to brighten up her apartment. Looking at the drab walls, Della tries to imagine them teeming with beloved, meaningful faces.

And then a period ensues where nothing seems to happen, nothing in the present, anyway. These interludes descend on Della more and more often lately. She’ll be looking for her address book, or making herself coffee, when suddenly she’ll be yanked back into the presence of people and objects she hasn’t thought about for years. These memories unsettle her not because they bring up unpleasant things (though they often do) but because their vividness so surpasses her day-to-day life that they make it feel as faded as an old blouse put through the wash too many times. One memory that keeps coming back lately is of that coal bin she had to sleep in as a child. This was after they moved up to Detroit from Paducah, and after her father ran off. Della, her mom, and her brother were living in a boardinghouse. Her mom and Glenn got regular rooms, in the upstairs, but Della had to sleep in the basement. You couldn’t even get to her room from inside the house. You had to go out to the backyard and lift doors that led down to the cellar. The landlady had whitewashed the room and put in a bed and some pillows made from flour sacks. But that didn’t fool Della. The door was made of metal, and there weren’t any windows. It was black as pitch down there. Oh, did I ever hate going down into that coal bin every night! It was like walking right down into a crypt!

But I never complained. Just did what I was told.

Della’s little house, in Contoocook, was the only place that was ever hers alone. Of course, at her age, it was getting to be a headache. Making it up her hill in the winter, or finding someone to shovel the snow off her roof so it didn’t cave in and bury her alive. Maybe Dr. Sutton, Bennett, and Robbie are right. Maybe she’s better off in this place.

When she looks out the window again Cathy’s car is nowhere to be seen. So Della picks up the book Cathy brought her. The blue mountains on the cover still baffle her. But the title’s the same: Two Old Women: An Alaska Legend of Betrayal, Courage and Survival. She opens the book and flips through it, stopping every so often to admire the drawings.

Then she goes back to page one. Focuses her eyes on the words and tracks them across the page. One sentence. Two. Then a whole paragraph. Since her last reading, she’s forgotten enough of the book that the story seems new again, yet familiar. Welcoming. But it’s mostly the act itself that brings relief, the self-forgetfulness, the diving and plunging into other lives.

Like so many books Della has read over the years, Two Old Women came recommended by Cathy. After she left the College of Nursing, Cathy went to work at a bookstore. She was remarried by then and had moved with Clark into an old farmhouse that she spent the next ten years fixing up.

Della memorized Cathy’s schedule and stopped in during her shifts, especially on Thursday evenings when customers were few and Cathy had time to talk.

That was the reason Della chose a Thursday to tell Cathy her news.

“Go on, I’m listening,” Cathy said. She was pushing a cart of books around the store, restocking, while Della sat in an armchair in the poetry section. Cathy had offered to make tea but Della said, “I’d just as soon have a beer.” Cathy had found one in the office refrigerator, left over from a book signing. It was after seven on an April night and the store was empty.

Della started telling Cathy how strangely her husband had been acting. She said she didn’t know what had got into him. “For instance, a few weeks ago, Dick gets out of bed in the middle of the night. Next thing I know, I heard his car backing down the drive. I thought to myself, ‘Well, maybe this is it. Maybe he’s had enough and that’s the last I’ll see of him.’”

“But he came back,” Cathy said, placing a book on a shelf.

“Yeah. About an hour later. I came downstairs and there he was. He was down on his knees, on the carpet, and he’s got all these road maps spread out all over.”

When Della asked her husband what on earth he was doing, Dick said that he was scouting for investment opportunities in Florida. Beachfront properties in undervalued areas that were reachable by direct flights from major cities. “I told him, ‘We’ve got enough money already. You can just retire and we’ll be fine. Why do you want to go and take a risk like that now?’ And do you know what he said to me? He said, ‘Retirement isn’t in my vocabulary.’”

Cathy disappeared into the self-help section. Della was too engrossed in telling her story to get up and follow. She hung her head dejectedly, staring at the floor. Her tone was full of wonder and outrage at the ideas men latched on to, especially as they got older. They were like fits of insanity, except that the husbands experienced these derangements as bolts of insight. “I just had an idea!” Dick was always saying. They could be doing anything, having dinner, going to a movie, when inspiration struck and he stopped dead in his tracks to announce, “Hey, I just had a thought.” Then he stood motionless, a finger to his chin, calculating, scheming.

His latest idea involved a resort near the Everglades. In the Polaroid he showed Della, the resort appeared as a charming but dilapidated hunting lodge surrounded by live oaks. What was different this time was that Dick had already acted on his idea. Without telling Della, he’d taken a mortgage on the place and used a chunk of their retirement savings as a down payment.

“We are now the proud owners of our own resort in the Florida Everglades!” he announced.

As much as it pained Della to tell Cathy this, it gave her pleasure as well. She held her beer bottle in both hands. The bookstore was quiet, the sky dark outside, the surrounding shops all closed for the night. It felt like they owned the place.

“So now we’re stuck with this doggone old resort,” Della said. “Dick wants to convert it into condos. To do that, he says he has to move down to Florida. And as usual he wants to drag me with him.”

Cathy re-emerged with the cart. Della expected to find a look of sympathy on her face but instead Cathy’s mouth was tight.

“So you’re moving?” she said coldly.

“I have to. He’s making me.”

“Nobody’s making you.”

This was spoken in Cathy’s recently acquired know-it-all tone. As if she’d read the entire self-help section and could now dispense psychological insight and marital advice.

“What do you mean, no one’s making me? Dick is.”

“What about your job?”

“I’ll have to quit. I don’t want to, I like working. But—”

“But you’ll give in as usual.”

This remark seemed not just unkind but unjust. What did Cathy expect Della to do? Divorce her husband after forty years of marriage? Get her own apartment and start dating strange men, the way Cathy was doing when they first met?

“You want to quit your job and go off to Florida, fine,” Cathy said. “But I have a job. And if you don’t mind, I’ve got some things to do before closing up.”

They had never had a fight before. In the following weeks, every time Della considered calling Cathy she found that she was too angry to do so. Who was Cathy to tell her how to run her marriage? She and Clark were at each other’s throats half the time.

A month later, just as Della was packing up the last boxes for the movers, Cathy appeared at her house.

“Are you mad at me?” Cathy said when Della opened the door.

“Well, you do sometimes think you know everything.”

That was maybe too mean, because Cathy burst out crying. She hunched forward and wailed in a pitiful voice, “I’m going to miss you, Della!”

Tears were streaming down her face. She opened her arms as if for a hug. Della didn’t approve of the first of these responses and she was hesitant about the second. “Now quit that,” she said. “You’re liable to start me crying, too.”

Cathy’s blubbering only got worse.

Alarmed, Della said, “We can still talk on the phone, Cathy. And write letters. And visit. You can come stay in our ‘resort.’ It’s probably full of snakes and alligators but you’re welcome.”

Cathy didn’t laugh. Through her tears, she said, “Dick won’t want me to visit. He hates me.”

“He doesn’t hate you.”

“Well, I hate him! He treats you like crap, Della. I’m sorry but that’s the truth. And now he’s making you quit your job and go down to Florida? To do what?”

“That’s enough of that,” Della said.

“OK! OK! I’m just so frustrated!”

Nevertheless, Cathy was calming down. After a moment, she said, “I brought you something.” She opened her purse. “This came into the store the other day. From a little publisher out in Alaska. We didn’t order it but I started reading it and I couldn’t put it down. I don’t want to give the story away, but, well—it just seems really appropriate! You’ll see when you read it.” She was looking into Della’s eyes. “Sometimes books come into your life for a reason, Della. It’s really strange.”

Della never knew what to do when Cathy got mystical on her. She sometimes claimed the moon affected her moods, and she invested coincidences with special meanings. On that day, Della thanked Cathy for the book and managed not to cry when they finally did hug goodbye.

The book had a drawing on the cover. Two Indians sitting in a tepee. Cathy was into all that kind of stuff, too, lately, stories about Native Americans or slave uprisings in Haiti, stories with ghosts or magical occurrences. Della liked some better than others.

She packed the book in a box of odds and ends that hadn’t been taped shut yet.

And then what happened to it? She shipped the box down to Florida with all the others. It turned out there wasn’t room for all their belongings in their one-bedroom at the hunting lodge, so they had to put them in storage. The resort went bust a year later. Soon Dick made Della move to Miami, and then to Daytona, and finally up to Hilton Head as he tried to make a go of other ventures. Only after he died, while Della was going through the bankruptcy, was she forced to open up the storage facility and sell off their furniture. Going through the boxes she’d shipped to Florida almost a decade before, she cut open the box of odds and ends and Two Old Women fell out.

The book is a retelling of an old Athabascan legend, which the author, Velma Wallis, heard growing up as a child. A legend handed down “from mothers to daughters” that told the story of the two old women of the title, Ch’idzigyaak and Sa’, who are left behind by their tribe during a time of famine.

Left behind to die, in other words. As was the custom.

Except the two old women don’t die. Out in the woods, they get to talking. Didn’t they used to know how to hunt and fish and forage for food? Couldn’t they do that again? And so that’s what they do, they relearn everything they knew as younger people, they hunt for prey and they go ice-fishing, and at one point they hide out from cannibals who pass through the territory. All kinds of stuff.

One drawing in the book showed the two women trekking across the Alaskan tundra. In hooded parkas and sealskin boots, they drag sleds behind them, the woman in front slightly less stooped than the other. The caption read: Our tribes have gone in search of food, in the land our grandfathers told us about, far over the mountains. But we have been judged unfit to follow them, because we walk with sticks, and are slow.

Certain passages stood out, like one with Ch’idzigyaak speaking:

“I know that you are sure of our survival. You are younger.” She could not help but smile bitterly at her remark, for just yesterday they both had been judged too old to live with the young.

“It’s just like the two of us,” Della said, when she finally read the book and called Cathy. “One’s younger than the other, but they’re both in the same fix.”

It started out as a joke. It was amusing to compare their own situations, in suburban Detroit and rural New Hampshire, with the existential plight of the old Inuit women. But the correspondences felt real, too. Della moved to Contoocook to be closer to Robbie but, two years later, Robbie moved to New York, leaving her stranded in the woods. Cathy’s bookstore closed. She started a pie-baking business out of her home. Clark retired and spent all day in front of the TV, entranced by pretty weather ladies on the news. Buxom, in snug, brightly colored dresses, they undulated before the weather maps, as though mimicking the storm fronts. All four of Cathy’s sons had left Detroit. They lived far away, on the other side of the mountains.

There was one illustration in the book that Della and Cathy particularly liked. It showed Ch’idzigyaak in the act of throwing a hatchet, while Sa’ looked on. The caption read, Perhaps if we see a squirrel, we can kill it with our hatchets, as we did when we were young.

That became their motto. Whenever one of them was feeling downhearted, or needed to deal with a problem, the other would call and say, “It’s hatchet time.”

Take charge, they meant. Don’t mope.

That was another quality they shared with the Inuit women. The tribe didn’t leave Ch’idzigyaak and Sa’ behind only because they were old. It was also because they were complainers. Always moaning about their aches and pains.

Husbands were often of the opinion that wives complained too much. But that was a complaint in itself. A way men had of shutting women up. Still, Della and Cathy knew that some of their unhappiness was their own fault. They let things fester, got into black moods, sulked. Even if their husbands asked what was wrong, they wouldn’t say. Their victimization felt too pleasurable. Relief would require no longer being themselves.

What was it about complaining that felt so good? You and your fellow sufferer emerging from a thorough session as if from a spa bath, refreshed and tingling?

Over the years Della and Cathy have forgotten about Two Old Women for long stretches. Then one of them will reread it, regain her enthusiasm, and get the other to reread it, too. The book isn’t in the same category as the detective stories and mysteries they consume. It’s closer to a manual for living. The book inspires them. They won’t stand to hear it maligned by their snobby sons. But now there’s no need to defend it. Two million copies sold! Anniversary editions! Proof enough of their sound judgment.

When Cathy arrives at Wyndham Falls the next morning, she can feel snow in the air. The temperature has dropped and there’s that stillness, no wind, all the birds in hiding.

She used to love such ominous quiet, as a girl, in Michigan. It promised school cancellations, time at home with her mother, the building of snow forts on the lawn. Even now, at seventy, big storms excite her. But her expectation now has a dark wish at its center, a desire for self-annihilation, almost, or cleansing. Sometimes, thinking about climate change, the world ending in cataclysms, Cathy says to herself, “Oh, just get it over with. We deserve it. Wipe the slate clean and start over.”

Della is dressed and ready to go. Cathy tells her she looks nice but can’t refrain from adding, “You have to tell the hairdresser not to use crème rinse, Della. Your hair’s too fine. Crème rinse flattens it down.”

“You try telling that lady anything,” Della says, as she pushes her walker down the hall. “She doesn’t listen.”

“Then get Bennett to take you to a salon.”

“Oh, sure. Fat chance.”

As they come outside, Cathy makes a note to e-mail Bennett. He might not understand how a little thing like that—getting her hair done—can lift a woman’s spirits.

It’s slow going with Della’s walker. She has to navigate along the sidewalk and down the curb to the parking lot. At the car, Cathy helps her into the passenger seat and then takes the walker around to put it in the trunk. It takes a while to figure out how to collapse it and flip up the seat.

A minute later, they’re on their way. Della leans forward in her seat, alertly scanning the road and giving Cathy directions.

“You know your way around already,” Cathy says approvingly.

“Yeah,” Della says. “Maybe those pills are working.”

Cathy would prefer to get the frames somewhere nice, a Pottery Barn or Crate & Barrel, but Della directs her to a Goodwill in a nearby strip mall. In the parking lot, Cathy performs the same operation in reverse, unfolding the walker and bringing it around so that Della can hoist herself to her feet. Once she gets going, she moves at a good clip.

By the time they get inside the store, it’s like old times. They move through the shiny-floored, fluorescently lit space as eagle-eyed as if on a scavenger hunt. Seeing a section of glassware, Della says, “Hey, I need some good new drinking glasses,” and they divert their operation.

The picture frames are way in the back of the store. Halfway there, the linoleum gives way to bare concrete. “I have to be careful about the floor in here,” Della says. “It’s sort of lippity.”

Cathy takes her arm. When they reach the aisle, she says, “Just stay here, Della. Let me look.”

As usual with secondhand merchandise, the problem is finding a matching set.

Nothing’s organized. Cathy flips through frame after frame, all of different sizes and styles. After a minute, she finds a set of matching simple black wooden frames. She’s pulling them out when she hears a sound behind her. Not a cry, exactly. Just an intake of breath. She turns to see Della with a look of surprise on her face. She has reached out to take a look at something—Cathy doesn’t know what—and let her hand slip off the handle of her walker.

Once, years ago, when Della and Dick had the sailboat, Della almost drowned. The boat was moored at the time and Della slipped trying to climb aboard, sinking down into the murky green water of the marina. “I never learned to swim, you know,” she told Cathy. “But I wasn’t scared. It was sort of peaceful down there. Somehow I managed to claw my way to the surface. Dick was hollering for the dock boy and finally he came and grabbed hold of me.”

Della’s face looks the way Cathy imagined it then, under the water. Mildly astonished. Serene. As though forces beyond her control have taken charge and there’s no sense resisting.

This time, wonderment fails to save her. Della falls sideways, into the shelving. The metal edge shaves the skin off her arm with a rasping sound like a meat slicer. Della’s temple strikes the shelf next. Cathy shouts. Glass shatters.

They keep Della at the hospital overnight. Perform an MRI to check for bleeding in the brain, X-ray her hip, apply a damp chamois bandage over her abraded arm, which will have to stay on for a week before they remove it to see if the skin will heal or not. At her age, it’s fifty-fifty.

All this is related to them by a Dr. Mehta, a young woman of such absurd glamour that she might play a doctor in a medical drama on TV. Two strands of pearls twine around her fluted throat. Her gray knit dress falls loosely over a curvaceous figure. Her only defect is her spindly calves, but she camouflages these with a pair of daring diamond-patterned stockings, and gray high heels that match her dress exactly. Dr. Mehta represents something Cathy isn’t quite prepared for, a younger generation of women surpassing her own not only in professional achievement but in the formerly retrograde department of self-beautification. Dr. Mehta has an engagement ring, too, with a sizeable diamond. Marrying some other doctor, probably, combining fat salaries.

“What if the skin doesn’t heal?” Cathy asks.

“Then she’ll have to keep the bandage on.”

“Forever?”

“Let’s just wait and see how it looks in a week,” Dr. Mehta says.

All this has taken hours. It’s seven in the evening. Aside from the arm bandage, Della has the beginning of a black eye.

At eight thirty, the decision is made to keep Della overnight for observation.

“You mean I can’t go home?” Della asks Dr. Mehta. She sounds forlorn.

“Not yet. We need to keep an eye on you.”

Cathy elects to stay in the room with Della through the night. The lime-green couch converts into a bed. The nurse promises to bring her a sheet and blanket.

Cathy is in the cafeteria, soothing herself with chocolate pudding, when Della’s sons appear.

Years ago, her son Mike got Cathy to watch a sci-fi movie about assassins who return to Earth from the future. It was the usual mayhem and preposterousness, but Mike, who was in college at the time, claimed that the movie’s acrobatic fight scenes were infused with profound philosophical meaning. Cartesian was the word he used.

Cathy didn’t get it. Nevertheless, it’s of that movie she thinks, now, as Bennett and Robbie enter the room. Their pale, unsmiling faces and dark suits make them look inconspicuous and ominous at once, like agents of a universal conspiracy.

Targeting her.

“It was all my fault,” Cathy says as they reach her table. “I wasn’t watching her.”

“Don’t blame yourself,” Bennett says.

This seems a mark of kindness, until he adds, “She’s old. She falls. It’s just part of the whole deal.”

“It’s a result of the ataxia,” Robbie says.

Cathy isn’t interested in what ataxia means. Another diagnosis. “She was doing fine right up until she fell,” she says. “We were having a good time. Then I turned my back for a second and—wham.”

“That’s all it takes,” Bennett said. “It’s impossible to prevent it.”

“The medicine she’s taking, the Aricept?” Robbie says. “It’s not much more than a palliative treatment. The benefits, if any, taper off after a year or two.”

“Your mom’s eighty-eight. Two years might be enough.”

The implication of this hangs in the air until Bennett says, “Except she keeps falling. And ending up in the hospital.”

“We’re going to have to move her,” Robbie says in a slightly louder, strained tone. “Wyndham’s not safe for her. She needs more supervision.”

Robbie and Bennett are not Cathy’s children. They’re older, and not as attractive. She feels no connection to them, no maternal warmth or love. And yet they remind her of her sons in ways she’d rather not think about.

Neither of them has offered to have Della come live with him. Robbie travels too much, he says. Bennett’s house has too many stairs. But it isn’t their selfishness that bothers Cathy the most. It’s how they stand before her now, infused—bloated—with rationality. They want to get this problem solved quickly and decisively, with minimum effort. By taking emotion out of the equation they’ve convinced themselves that they’re acting prudently, even though their wish to settle the situation arises from nothing but emotions—fear, mainly, but also guilt, and irritation.

And who is Cathy to them? Their mom’s old friend. The one who worked in the bookstore. The one who got her stoned.

Cathy turns away to look across the cafeteria, filling up now with medical staff coming in on their dinner break. She feels tired.

“OK,” she says. “But don’t tell her now. Let’s wait.”

The machines click and whir through the night. Every so often an alarm sounds on the monitors, waking Cathy up. Each time a nurse appears, never the same one, and presses a button to silence it. The alarm means nothing, apparently.

It’s freezing in the room. The ventilation system blows straight down on her. The blanket she’s been given is as thin as paper toweling.

A friend of Cathy’s in Detroit, a woman who has seen a therapist regularly for the past thirty years, recently passed on advice the therapist had given her. Pay no attention to the terrors that visit you in the night. The psyche is at its lowest ebb then, unable to defend itself. The desolation that envelops you feels like truth, but isn’t. It’s just mental fatigue masquerading as insight.

Cathy reminds herself of this as she lies sleepless on the slab of mattress. Her impotence in helping Della has filled her mind with nihilistic thoughts. Cold, clear recognitions, lacerating in their strictness. She has never known who Clark is. Theirs is a marriage devoid of intimacy. If Mike, John, Chris, and Palmer weren’t her children, they would be people of whom she disapproves. She has spent her life catering to people who disappear, like the bookstore she used to work in.

Sleep finally comes. When Cathy wakes the next morning, feeling stiff, she is relieved to see that the therapist was right. The sun is up and the universe isn’t so bleak. Yet some darkness must remain. Because she’s made her decision. The idea of it burns inside her. It’s neither nice nor kind. Such a novel feeling that she doesn’t know what to call it.

Cathy is sitting next to Della’s bed when Della opens her eyes. She doesn’t tell her about the nursing home. She only says, “Good morning, Della. Hey, guess what time it is?”

Della blinks, still groggy from sleep. And Cathy answers, “It’s hatchet time.”

It begins snowing as they cross the Massachusetts state line. They’re about two hours from Contoocook, the GPS a beacon in the sudden loss of visibility.

Clark will see this on the Weather Channel. He’ll call or text her, concerned about her flight being canceled.

Poor guy has no idea.

Now that they’re in the car, with the wipers and the defroster going, it appears that Della doesn’t quite grasp the situation. She keeps asking Cathy the same questions.

“So how will we get in the house?”

“You said Gertie has a key.”

“Oh, right. I forgot. So we can get the key from Gertie and get into the house. It’ll be cold as the dickens in there. We were keeping it at about fifty to save on oil. Just warm enough to keep the pipes from freezing.”

“We’ll warm it up when we get there.”

“And then I’m going to stay there?”

“We both will. Until we get things sorted out. We can get one of those home health aides. And Meals on Wheels.”

“That sounds expensive.”

“Not always. We’ll look into it.”

Repeating this information helps Cathy to believe in it. Tomorrow, she’ll call Clark and tell him that she’s going to stay with Della for a month, maybe more, maybe less. He won’t like it, but he’ll cope. She’ll make it up to him somehow.

Bennett and Robbie present a greater problem. Already she has three messages from Bennett and one from Robbie on her phone, plus voice mails asking where she and Della are.

It was easier than Cathy expected to sneak Della out of the hospital. Her IV had been taken out, luckily. Cathy just walked her down the hall, as though for exercise, then headed for the elevator. All the way to the car she kept expecting an alarm to sound, security guards to come running. But nothing happened.

The snow is sticking to trees but not the highway yet. Cathy exits the slow lane when traffic gets light. She exceeds the speed limit, eager to get where they’re going before nightfall.

“Bennett and Robbie aren’t going to like this,” Della says, looking out at the churning snow. “They think I’m too stupid to live on my own now. Which I probably am.”

“You won’t be alone,” Cathy says. “I’ll stay with you until we get things sorted out.”

“I don’t know if dementia is the kind of thing you can sort out.”

Just like that: the malady named and identified. Cathy looks at Della to see if she’s aware of this change, but her expression is merely resigned.

By the time they reach Contoocook, the snow is deep enough that they fear they won’t make it up the drive. Cathy takes the slope at a good speed and, after a slight skid, powers to the top. Della cheers. Their return has begun on a note of triumph.

“We’ll have to get groceries in the morning,” Cathy says. “It’s snowing too hard to go now.”

The following morning, however, snow is still coming down. It continues throughout the day, while Cathy’s voice mail fills with more calls from Robbie and Bennett. She doesn’t dare answer them.

Once, early in her friendship with Della, Cathy forgot to leave dinner in the fridge for Clark to heat up. When she came home later that night, he got on her right away. “What is it with the two of you?” Clark said. “Christ. Like a couple of lezzies.”

It wasn’t that. Not an overflow of forbidden desire. Just a way of compensating for areas of life that produced less contentment than advertised. Marriage, certainly. Motherhood more often than they liked to admit.

There’s a ladies’ group Cathy has read about in the newspapers, a kind of late-life women’s movement. The members, middle-aged and older, dress up to the nines and wear elaborate, brightly colored hats—pink or purple, she can’t remember which. The group is known for these hats, in which its members swoop down on restaurants and fill entire sections. No men allowed. The women dress up for one another, to hell with everyone else. Cathy thinks this sounds like fun. When she’s asked Della about it, Della says, “I’m not dressing up and putting on some stupid hat just to have dinner with a bunch of people I probably don’t even want to talk to. Besides, I don’t have any good clothes anymore.”

Cathy might do it alone. After she gets Della settled. When she’s back in Detroit.

In the freezer, Cathy finds some bagels, which she defrosts in the microwave. There are also frozen dinners, and coffee. They can drink it black.

Her face is still pretty banged up but otherwise Della feels fine. She is happy to be out of the hospital. It was impossible to sleep in that place, with all the noise and commotion, people coming in to check on you all the time or to wheel you down for some test.

Either that or no one came to help you at all, even if you buzzed and buzzed.

Heading off into a snowstorm seemed crazy, but it was lucky they left when they did. If they’d waited another day, they would never have made it to Contoocook. Her hill was slippery by the time they arrived. Snow covered the walk and back steps. But then they were inside the house and the heat was on and it felt cozy with the snow falling at every window, like confetti.

On TV the weather people are in a state, reporting on the blizzard. Boston and Providence are shut down. Sea waves have swept ashore and frozen solid, encasing houses in ice.

They are snowed in for a week. The drifts rise halfway up the back door. Even if they could get to the car, there’s no way to get down the drive. Cathy has had to call the rental agency and extend her lease, which Della feels bad about. She has offered to pay but Cathy won’t let her.

On their third day as shut-ins, Cathy jumps up from the couch and says, “The tequila! Don’t we still have some of that?” In the cupboard above the stove she finds a bottle of tequila and another, half full, of margarita mix.

“Now we can survive for sure,” Cathy says, brandishing the bottle. They both laugh.

Every evening around six, just before they turn on Brian Williams, they make frozen margaritas in the blender. Della wonders if drinking alcohol is a good idea with her malady. On the other hand, who’s going to tell on her?

“Not me,” Cathy says. “I’m your enabler.”

Some days it snows again, which makes Della jumble up the time. She’ll think that the blizzard is still going on and that she’s just returned from the hospital.

One day she looks at her calendar and sees it is February. A month has gone by. In the bathroom mirror her black eye is gone, just a smear of yellow at the corner remains.

Every day Della reads a little of her book. It seems to her that she is performing this task more or less competently. Her eyes move over the words, which in turn sound in her head, and give rise to pictures. The story is as engrossing and swift as she remembers. Sometimes she can’t tell if she is rereading the book or just remembering passages from having read them so often. But she decides the difference doesn’t matter much.

“Now we really are like those two old women,” Della says one day to Cathy.

“I’m still the younger one, though. Don’t forget that.”

“Right. You’re young old and I’m just plain old old.”

They don’t need to hunt or forage for food. Della’s neighbor Gertie, who was a minister’s wife, treks up from her house to bring them bread, milk, and eggs from the Market Basket. Lyle, who lives behind Della, crosses the snowy yard to bring other supplies. The power stays on. That’s the main thing.

At some point Lyle, who has a side job plowing people out during the winter, gets around to plowing Della’s drive, and after that Cathy takes the rental car to get groceries.

People start coming to the house. A male physical therapist who makes Della do balance exercises and is very strict with her. A visiting nurse who takes her vitals. A girl from the area who cooks simple meals on nights when Della doesn’t use the microwave.

Cathy is gone by that point. Bennett is there instead. He comes up on the weekends and stays through Sunday night, getting up early to drive to work on Monday morning. A few months later, when Della gets bronchitis and wakes up unable to breathe, and is again taken to the hospital by EMS, it is Robbie who comes up, from New York, to stay for a week until she’s feeling better.

Sometimes Robbie brings his girlfriend, a Canadian gal from Montreal who breeds dogs for a living. Della doesn’t ask much about this woman, though she is friendly to her face. Robbie’s private life isn’t her concern anymore. She won’t be around long enough for it to matter.

She picks up Two Old Women from time to time to read a little more, but she never seems to get through the whole thing. That doesn’t matter either. She knows how the book ends. The two old women survive through the harsh winter, and when their tribe comes back, still all starving, the two women teach them what they’ve learned. And from that time on those particular Indians never leave their old people behind anymore.

A lot of the time Della is alone in the house. The people who come to help her have left for the day, or it’s their day off, and Bennett is busy. It’s winter again. Two years have passed. She’s almost ninety. She doesn’t seem to be getting any stupider, or only a little bit. Not enough to notice.

One day, it snows again. Stopping at the window, Della is possessed by an urge to go outside and move into it. As far as her old feet will take her. She wouldn’t even need her walker. Wouldn’t need anything. Looking at the snow, blowing around beyond the window glass, Della has the feeling that she’s peering into her own brain. Her thoughts are like that now, constantly circulating, moving from one place to another, just a whole big whiteout inside her head. Going out in the snow, disappearing into it, wouldn’t be anything new to her. It would be like the outside meeting the inside. The two of them merging. Everything white. Just walk on out. Keep going. Maybe she’d meet someone out there, maybe she wouldn’t. A friend.

2017

AIR MAIL (#ulink_84ba6f8d-0ca5-594f-aa1e-433035ec8330)

Through the bamboo Mitchell watched the German woman, his fellow invalid, making another trip to the outhouse. She came out onto the porch of her hut, holding a hand over her eyes—it was murderously sunny out—while her other, somnambulistic hand searched for the beach towel hanging over the railing. Finding it, she draped the towel loosely, only just extenuatingly, over her otherwise unclothed body, and staggered out into the sun. She came right by Mitchell’s hut. Through the slats her skin looked a sickly, chicken-soup color. She was wearing only one flip-flop. Every few steps she had to stop and lift her bare foot out of the blazing sand. Then she rested, flamingo style, breathing hard. She looked as if she might collapse. But she didn’t. She made it across the sand to the edge of the scrubby jungle. When she reached the outhouse, she opened the door and peered into the darkness. Then she consigned herself to it.

Mitchell dropped his head back to the floor. He was lying on a straw mat, with a plaid L.L.Bean bathing suit for a pillow. It was cool in the hut and he didn’t want to get up himself. Unfortunately, his stomach was erupting. All night his insides had been quiet, but that morning Larry had persuaded him to eat an egg, and now the amoebas had something to feed on. “I told you I didn’t want an egg,” he said now, and only then remembered that Larry wasn’t there. Larry was off down the beach, partying with the Australians.

So as not to get angry, Mitchell closed his eyes and took a series of deep breaths. After only a few, the ringing started up. He listened, breathing in and out, trying to pay attention to nothing else. When the ringing got even louder, he rose on one elbow and searched for the letter he was writing to his parents. The most recent letter. He found it tucked into Ephesians, in his pocket New Testament. The front of the aerogram was already covered with handwriting. Without bothering to reread what he’d written, he grabbed the ballpoint pen—wedged at the ready in the bamboo—and began:

Do you remember my old English teacher, Mr. Dudar? When I was in tenth grade, he came down with cancer of the esophagus. It turned out he was a Christian Scientist, which we never knew. He refused to have chemotherapy even. And guess what happened? Absolute and total remission.

The tin door of the outhouse rattled shut and the German woman emerged into the sun again. Her towel had a wet stain. Mitchell put down his letter and crawled to the door of his hut. As soon as he stuck out his head, he could feel the heat. The sky was the filtered blue of a souvenir postcard, the ocean one shade darker. The white sand was like a tanning reflector. He squinted at the silhouette hobbling toward him.

“How are you feeling?”

The German woman didn’t answer until she reached a stripe of shade between the huts. She lifted her foot and scowled at it. “When I go, it is just brown water.”

“It’ll go away. Just keep fasting.”

“I am fasting three days now.”

“You have to starve the amoebas out.”

“Ja, but I think the amoebas are maybe starving me out.” Except for the towel she was still naked, but naked like a sick person. Mitchell didn’t feel anything. She waved and started walking away.

When she was gone, he crawled back into his hut and lay on the mat again. He picked up the pen and wrote, Mohandas K. Gandhi used to sleep with his grandnieces, one on either side, to test his vow of chastity—i.e., saints are always fanatics.

He laid his head on the bathing suit and closed his eyes. In a moment, the ringing started again.

It was interrupted some time later by the floor shaking. The bamboo bounced under Mitchell’s head and he sat up. In the doorway, his traveling companion’s face hung like a harvest moon. Larry was wearing a Burmese lungi and an Indian silk scarf. His chest, hairier than you expected on a little guy, was bare, and sunburned as pink as his face. His scarf had metallic gold and silver threads and was thrown dramatically over one shoulder. He was smoking a bidi, half bent over, looking at Mitchell.

“Diarrhea update,” he said.

“I’m fine.”

“You’re fine?”

“I’m OK.”

Larry seemed disappointed. The pinkish, sunburned skin on his forehead wrinkled. He held up a small glass bottle. “I brought you some pills. For the shits.”

“Pills plug you up,” Mitchell said. “Then the amoebas stay in you.”

“Gwendolyn gave them to me. You should try them. Fasting would have worked by now. It’s been what? Almost a week?”

“Fasting doesn’t include being force-fed eggs.”

“One egg,” said Larry, waving this away.

“I was all right before I ate that egg. Now my stomach hurts.”

“I thought you said you were fine.”

“I am fine,” said Mitchell, and his stomach erupted. He felt a series of pops in his lower abdomen, followed by an easing, as of liquid being siphoned off; then from his bowels came the familiar insistent pressure. He turned his head away, closing his eyes, and began to breathe deeply again.

Larry took a few more drags on the bidi and said, “You don’t look so good to me.”

“You,” said Mitchell, still with his eyes closed, “are stoned.”

“You betcha” was Larry’s response. “Which reminds me. We ran out of papers.” He stepped over Mitchell, and the array of aerograms, finished and unfinished, and the tiny New Testament, into his—that is, Larry’s—half of the hut. He crouched and began searching through his bag. Larry’s bag was made of a rainbow-colored burlap. So far, it had never passed through customs without being exhaustively searched. It was the kind of bag that announced, “I am carrying drugs.” Larry found his chillum, removed the stone bowl, and knocked out the ashes.

“Don’t do that on the floor.”

“Relax. They fall right through.” He rubbed his fingers back and forth. “See? All tidy.”

He put the chillum to his mouth to make sure that it was drawing. As he did so he looked sideways at Mitchell. “Do you think you’ll be able to travel soon?”

“I think so.”

“Because we should probably be getting back to Bangkok. I mean, eventually. I’m up for Bali. You up?”

“As soon as I’m up,” said Mitchell.

Larry nodded, once, as though satisfied. He removed the chillum from his mouth and reinserted the bidi. He stood, hunching over beneath the roof, and stared at the floor.

“The mail boat comes tomorrow.”

“What?”

“The mail boat. For your letters.” Larry pushed a few around with his foot. “You want me to mail them for you? You have to go down to the beach.”

“I can do it. I’ll be up tomorrow.”

Larry raised one eyebrow but said nothing. Then he started for the door. “I’ll leave these pills in case you change your mind.”

As soon as he was gone, Mitchell got up. There was no putting it off any longer. He retied his lungi and stepped out on the porch, covering his eyes. He kicked around for his flip-flops. Beyond, he was aware of the beach and the shuffling waves. He came down the steps and started walking. He didn’t look up. He saw only his feet and the sand rolling past. The German woman’s footprints were still visible, along with pieces of litter, shredded packages of Nescafé or balled-up paper napkins that blew from the cook tent. He could smell fish grilling. It didn’t make him hungry.

The outhouse was a shack of corrugated tin. Outside sat a rusted oil drum of water and a small plastic bucket. Mitchell filled the bucket and took it inside. Before closing the door, while there was still light to see, he positioned his feet on the platform to either side of the hole. Then he closed the door and everything became dark. He undid his lungi and pulled it up, hanging the fabric around his neck. Using Asian toilets had made him limber: he could squat for ten minutes without strain. As for the smell, he hardly noticed it anymore. He held the door closed so that no one would barge in on him.

The sheer volume of liquid that rushed out of him still surprised him, but it always came as a relief. He imagined the amoebas being swept away in the flood, swirling down the drain of himself and out of his body. The dysentery had made him intimate with his insides; he had a clear sense of his stomach, of his colon; he felt the smooth muscular piping that constituted him. The combustion began high in his intestines. Then it worked its way along, like an egg swallowed by a snake, expanding, stretching the tissue, until, with a series of shudders, it dropped, and he exploded into water.

He’d been sick not for a week but for thirteen days. He hadn’t said anything to Larry at first. One morning in a guesthouse in Bangkok, Mitchell had awoken with a queasy stomach. Once up and out of his mosquito netting, though, he’d felt better. Then that night after dinner, there’d come a series of taps, like fingers drumming on the inside of his abdomen. The next morning the diarrhea started. That was no big deal. He’d had it before in India, but it had gone away after a few days. This didn’t. Instead, it got worse, sending him to the bathroom a few times after every meal. Soon he started to feel fatigued. He got dizzy when he stood up. His stomach burned after eating. But he kept on traveling. He didn’t think it was anything serious. From Bangkok, he and Larry took a bus to the coast, where they boarded a ferry to the island. The boat puttered into the small cove, shutting off its engine in the shallow water. They had to wade to shore. Just that—jumping in—had confirmed something. The sloshing of the sea mimicked the sloshing in Mitchell’s gut. As soon as they got settled, Mitchell had begun to fast. For a week now he’d consumed nothing but black tea, leaving the hut only for the outhouse. Coming out one day, he’d run into the German woman and had persuaded her to start fasting, too. Otherwise, he lay on his mat, thinking and writing letters home.

Greetings from paradise. Larry and I are currently staying on a tropical island in the Gulf of Siam (check the world atlas). We have our own hut right on the beach, for which we pay the princely sum of five dollars per night. This island hasn’t been discovered yet so there’s almost nobody here. He went on, describing the island (or as much as he could glimpse through the bamboo), but soon returned to more important preoccupations. Eastern religion teaches that all matter is illusory. That includes everything, our house, every one of Dad’s suits, even Mom’s plant hangers—all maya,according to the Buddha. That category also includes, of course, the body. One of the reasons I decided to take this grand tour was that our frame of reference back in Detroit seemed a little cramped. And there are a few things I’ve come to believe in. And to test. One of which is that we can control our bodies with our minds. They have monks in Tibet who can mentally regulate their physiologies. They play a game called “melting snowballs.” They put a snowball in one hand and then meditate, sending all their internal heat to that hand. The one who melts the snowball fastest wins.

From time to time, he stopped writing to sit with his eyes closed, as though waiting for inspiration. And that was exactly how he’d been sitting two months earlier—eyes closed, spine straight, head lifted, nose somehow alert—when the ringing started. It had happened in a pale green Indian hotel room in Mahabalipuram. Mitchell had been sitting on his bed, in the half-lotus position. His inflexible left, Western knee stuck way up in the air. Larry was off exploring the streets. Mitchell was all alone. He hadn’t even been waiting for anything to happen. He was just sitting there, trying to meditate, his mind wandering to all sorts of things. For instance, he was thinking about his old girlfriend, Christine Woodhouse, and her amazing red pubic hair, which he’d never get to see again. He was thinking about food. He was hoping they had something in this town besides idli sambar. Every so often he’d become aware of how much his mind was wandering, and then he’d try to direct it back to his breathing. Then, sometime in the middle of all this, when he least expected it, when he’d stopped even trying or waiting for anything to happen (which was exactly when all the mystics said it would happen), Mitchell’s ears had begun to ring. Very softly. It wasn’t an unfamiliar ringing. In fact, he recognized it. He could remember standing in the front yard one day as a little kid and suddenly hearing this ringing in his ears, and asking his older brothers, “Do you hear that ringing?” They said they didn’t but knew what he was talking about. In the pale green hotel room, after almost twenty years, Mitchell heard it again. He thought maybe this ringing was what they meant by the Cosmic Om. Or the music of the spheres. He kept trying to hear it after that. Wherever he went, he listened for the ringing, and after a while he got pretty good at hearing it. He heard it in the middle of Sudder Street in Calcutta, with cabs honking and street urchins shouting for baksheesh. He heard it on the train up to Chiang Mai. It was the sound of the universal energy, of all the atoms linking up to create the colors before his eyes. It had been right there the whole time. All he had to do was wake up and listen to it.

He wrote home, at first tentatively, then with growing confidence, about what was happening to him. The energy flow of the universe is capable of being appercepted. We are, each of us, finely tuned radios. We just have to blow the dust off our tubes. He sent his parents a few letters each week. He sent letters to his brothers, too. And to his friends. Whatever he was thinking, he wrote down. He didn’t consider people’s reactions. He was seized by a need to analyze his intuitions, to describe what he saw and felt. Dear Mom and Dad, I watched a woman being cremated this afternoon. You can tell if it’s a woman by the color of the shroud. Hers was red. It burned off first. Then her skin did. While I was watching, her intestines filled up with hot gas, like a great big balloon. They got bigger and bigger until they finally popped. Then all this fluid came out. I tried to find something similar on a postcard for you but no such luck.

Or else: Dear Petie, Does it ever occur to you that this world of earwax remover and embarrassing jock itch might not be the whole megillah? Sometimes it looks that way to me. Blake believed in angelic recitation. And who knows? His poems back him up. Sometimes at night, though, when the moon gets that very pale thing going, I swear I feel a flutter of wings against the three-day growth on my cheeks.

Mitchell had called home only once, from Calcutta. The connection had been bad. It was the first time Mitchell and his parents had experienced the transatlantic delay. His father answered. Mitchell said hello, hearing nothing until his last syllable, the o, echoed in his ears. After that, the static changed registers, and his father’s voice came through. Traveling over half the globe, it lost some of its characteristic force. “Now listen, your mother and I want you to get on a plane and get yourself back home.”

“I just got to India.”

“You’ve been gone six months. That’s long enough. We don’t care what it costs. Use that credit card we gave you and buy yourself a ticket back home.”

“I’ll be home in two months or so.”

“What the hell are you doing over there?” his father shouted, as best he could, against the satellite. “What is this about dead bodies in the Ganges? You’re liable to come down with some disease.”

“No, I won’t. I feel fine.”

“Well, your mother doesn’t feel fine. She’s worried half to death.”

“Dad, this is the best part of the trip so far. Europe was great and everything, but it’s still the West.”

“And what’s wrong with the West?”

“Nothing. Only it’s more exciting to get away from your own culture.”

“Speak to your mother,” his father said.

And then his mother’s voice, almost a whimper, had come over the line. “Mitchell, are you OK?”

“I’m fine.”

“We’re worried about you.”

“Don’t worry. I’m fine.”

“You don’t sound right in your letters. What’s going on with you?”

Mitchell wondered if he could tell her. But there was no way to say it. You couldn’t say, I’ve found the truth. People didn’t like that.

“You sound like one of those Hare Krishnas.”

“I haven’t joined up yet, Mom. So far, all I’ve done is shave my head.”

“You shaved your head, Mitchell!”

“No,” he told her; though in fact it was true: he had shaved his head.

Then his father was back on the line. His voice was strictly business now, a gutter voice Mitchell hadn’t heard before. “Listen, stop cocking around over there in India and get your butt back home. Six months is enough traveling. We gave you that credit card for emergencies and we want you …” Just then, a divine stroke, the line had gone dead. Mitchell had been left holding the receiver, with a queue of Bengalis waiting behind him. He’d decided to let them have their turns. He hung up the receiver, thinking that he shouldn’t call home again. They couldn’t possibly understand what he was going through or what this marvelous place had taught him. He’d tone down his letters, too. From now on, he’d stick to scenery.

But, of course, he hadn’t. No more than five days had passed before he was writing home again, describing the incorruptible body of Saint Francis Xavier and how it had been carried through the streets of Goa for four hundred years until an overzealous pilgrim had bitten off the saint’s finger. Mitchell couldn’t help himself. Everything he saw—the fantastical banyan trees, the painted cows—made him start writing, and after he described the sights, he talked about their effect on him, and from the colors of the visible world he moved straightaway into the darkness and ringing of the invisible. When he got sick, he’d written home about that, too. Dear Mom and Dad, I think I have a touch of amoebic dysentery. He’d gone on to describe the symptoms, the remedies the other travelers used. Everybody gets it sooner or later. I’m just going to fast and meditate until I get better. I’ve lost a little weight, but not much. Soon as I’m better, Larry and I are off to Bali.

He was right about one thing: sooner or later, everybody did get it. Besides his German neighbor, two other travelers on the island had been suffering from stomach complaints. One, a Frenchman, laid low by a salad, had taken to his hut, from which he’d groaned and called for help like a dying emperor. But just yesterday Mitchell had seen him restored to health, rising out of the shallow bay with a parrotfish impaled on the end of his spear gun. The other victim had been a Swedish woman. Mitchell had last seen her being carried out, limp and exhausted, to the ferry. The Thai boatmen had pulled her aboard with the empty soda bottles and fuel containers. They were used to the sight of languishing foreigners. As soon as they’d stowed the woman on deck, they’d started smiling and waving. Then the boat had kicked into reverse, taking the woman back to the clinic on the mainland.

If it came to that, Mitchell knew he could always be evacuated. He didn’t, however, expect it to come to that. Once he’d gotten the egg out of his system, he felt better. The pain in his stomach went away. Four or five times a day he had Larry bring him black tea. He refused to give the amoebas so much as a drop of milk to feed on. Contrary to what he would’ve expected, his mental energy didn’t diminish but actually increased. It’s incredible how much energy is taken up with the act of digestion. Rather than being some weird penance, fasting is actually a very sane and scientific method of quieting the body, of turning the body off. And when the body turns off, the mind turns on. The Sanskrit for this is moksa,which means total liberation from the body.

The strange thing was that here, in the hut, verifiably sick, Mitchell had never felt so good, so tranquil, or so brilliant in his life. He felt secure and watched over in a way he couldn’t explain. He felt happy. This wasn’t the case with the German woman. She looked worse and worse. She hardly spoke when they passed now. Her skin was paler, splotchier. After a while Mitchell stopped encouraging her to keep fasting. He lay on his back, with the bathing suit over his eyes now, and paid no attention to her trips to the outhouse. He listened instead to the sounds of the island, people swimming and shouting on the beach, somebody learning to play a wooden flute a few huts down. Waves lapped, and occasionally a dead palm leaf or coconut fell to the ground. At night, the wild dogs began howling in the jungle. When he went to the outhouse, Mitchell could hear them moving around outside, coming up and sniffing him, the flow of his waste, through the holes in the walls. Most people banged flashlights against the tin door to scare the dogs away. Mitchell didn’t even bring a flashlight along. He stood listening to the dogs gather in the vegetation. With sharp muzzles they pushed stalks aside until their red eyes appeared in the moonlight. Mitchell faced them down, serenely. He spread out his arms, offering himself, and when they didn’t attack, he turned and walked back to his hut.

One night as he was coming back, he heard an Australian voice say, “Here comes the patient now.” He looked up to see Larry and an older woman sitting on the porch of the hut. Larry was rolling a joint on his Let’s Go: Asia. The woman was smoking a cigarette and looking straight at Mitchell. “Hello, Mitchell, I’m Gwendolyn,” she said. “I hear you’ve been sick.”

“Somewhat.”

“Larry says you haven’t been taking the pills I sent over.”