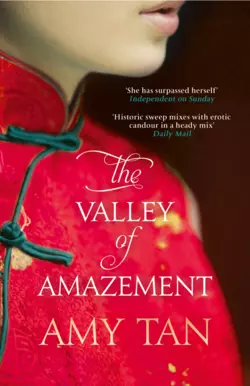

The Valley of Amazement

Amy Tan

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 619.36 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Shanghai, 1905. Violet Minturn is the young daughter of the American mistress of the city’s most exclusive courtesan house. But when revolution arrives in the city, she is separated from her mother in a cruel act of chicanery and forced to become a ‘virgin courtesan’.Half-Chinese and half-American, Violet moves effortlessly between the cultural worlds of East and West, quickly becoming a shrewd businesswoman who deals in seduction and illusion. But her successes belie her private struggle to understand who she really is and her search for a home in the world.Lucia, Violet’s mother, nurses wounds of her own, first sustained when, as a teenager, she fell blindly in love with a Chinese painter and followed him from San Francisco to Shanghai, only to be confronted with the shocking reality of the vast cultural differences between them. Violet’s need for answers will propel both her and her mother on separate quests of discovery: journeys to make sense of their lives, of the men – fathers, lovers, sons – who have shaped them, and of the ways we fail one another and our children despite our best attempts to love and be loved.Spanning fifty years and two continents, ‘The Valley of Amazement’ resurrects lost worlds: from the moment when China’s imperial dynasty collapsed, a Republic arose, and foreign trade became the lifeblood of Shanghai, to the inner workings of courtesan houses and the lives of the foreign ‘Shanghailanders’ living in the International Settlement, both erased by World War II. It is also a deeply evocative narrative of family secrets, the legacy of trauma, and the profound connections between mothers and daughters, which returns readers to the compelling territory so expertly mapped in ‘The Joy Luck Club’.With her characteristic wisdom, grace and humour, Amy Tan conjures a story of the inheritance of love, its mysteries and betrayals, and its illusions and truths.