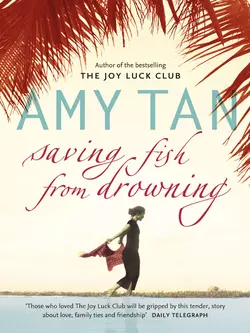

Saving Fish From Drowning

Amy Tan

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Фэнтези про драконов

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 774.44 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Please note that due to the limitations of some ereading devices, it was not possible to represent diacritical marks in this title.The highly anticipated novel from the bestselling author of ‘The Joy Luck Club’ and ‘The Bonesetter’s Daughter’.On an ill-fated art expedition of the Southern Shan State in Burma, eleven Americans leave their Floating Island Resort for a Christmas morning tour – and disappear. Through the twists of fate, curses and just plain human error, they find themselves deep in the Burma jungle, where they encounter a tribe awaiting the return of the leader and the mythical book of wisdom that will protect them from the ravages and destruction of the Myanmar military regime.Filled with Amy Tan’s signature ‘idiosyncratic, sympathetic characters, haunting images, historical complexity, significant contemporary themes, and suspenseful mystery’ (Los Angeles Times), ‘Saving Fish from Drowning’ seduces the reader with a façade of Buddhist illusions, magical tricks and light comedy, even as the absurd and picaresque spiral into a gripping morality tale about the consequences of intentions – both good and bad – and of the shared responsibility that individuals must accept for the actions of others.