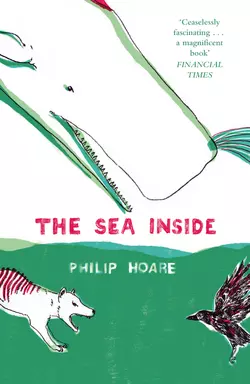

The Sea Inside

Philip Hoare

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Зарубежная образовательная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 619.36 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The sea surrounds us. It gives us life, provides us with the air we breathe and the food we eat. It is where we came from, and it carries our commerce. It represents home and migration, ceaseless change and constant presence. It covers two-thirds of our planet. Yet caught up in our everyday lives, we seem to ignore it, and what it means.In The Sea Inside, Philip Hoare sets out to rediscover the sea, its islands, birds and beasts. He begins on the south coast where he grew up, a place of family memory and an abiding sense of aloneness and almost monastic escape offered by the sea. From there he travels to the other side of the world, from the Isle of Wight to the Azores, from Sri Lanka to Tasmania and New Zealand, in search of encounters with animals and people – the wild and the tamed, the living and the extinct. Navigating between human and natural history, between science and myth, he asks what their stories mean for us now, in the twenty-first century, when the sea has never been so important to our present, as well as to our past and future.Along the way we meet an amazing cast of recluses, outcasts, and travellers; from eccentric artists and scientists to miracle-working saints and tattooed warriors; from gothic ravens to the greatest whales and bizarre creatures that may, or may not, be extinct. The Sea Inside is part bestiary, part memoir, part fantastical travelogue. It takes us on a magical journey of discovery, filled with astounding tales of faith and fear, wilderness and destruction, mortality and beauty. But more than anything, it is the story of the natural world, and the sea inside us all.