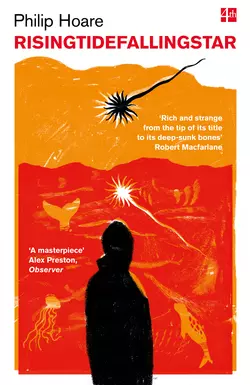

RISINGTIDEFALLINGSTAR

Philip Hoare

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1085.51 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Rich and strange from the tip of its title to its deep-sunk bones’ Robert MacfarlaneFrom the author of Leviathan, or, The Whale, comes a composite portrait of the subtle, beautiful, inspired and demented ways in which we have come to terms with our watery planet.In the third of his watery books, the author goes in pursuit of human and animal stories of the sea. Of people enchanted or driven to despair by the water, accompanied by whales and birds and seals – familiar spirits swimming and flying with the author on his meandering odyssey from suburbia into the unknown.Along the way, he encounters drowned poets and eccentric artists, modernist writers and era-defining performers, wild utopians and national heroes – famous or infamous, they are all surprisingly, and sometimes fatally, linked to the sea.Out of the storm-clouds of the twenty-first century and our restive time, these stories reach back into the past and forward into the future. This is a shape-shifting world that has never been certain, caught between the natural and unnatural, where the state between human and animal is blurred. Time, space, gender and species become as fluid as the sea.Here humans challenge their landbound lives through art or words or performance or myth, through the animal and the elemental. And here they are forever drawn back to the water, forever lost and found on the infinite sea.