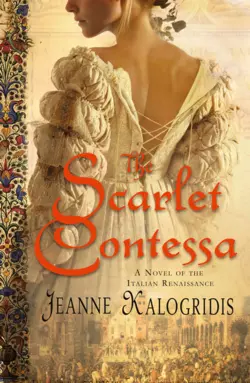

The Scarlet Contessa

Jeanne Kalogridis

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 510.72 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: From Jeanne Kalogridis, critically acclaimed author of The Borgia Bride, Painting Mona Lisa and The Devil’s Queen, comes another irresistible historical novel about a countess whose passion and willfulness knew no bounds: Caterina Sforza.Daughter of the Duke of Milan and wife of the conniving Count Girolamo Riario, Caterina Sforza was the bravest warrior Renaissance Italy ever knew. She ruled her own lands, fought her own battles, and openly took lovers whenever she pleased.Her remarkable tale is told by her lady-in-waiting, Dea, a woman knowledgeable in reading the ‘triumph cards’ – the predecessor of modern-day Tarot. As Dea tries to unravel the truth about her husband’s murder, Caterina single-handedly holds off invaders who would steal her title and lands. However, Dea’s reading of the cards reveals that Caterina cannot withstand a third and final invader – none other than Cesare Borgia, son of the corrupt Pope Alexander VI, who has an old score to settle with Caterina. Trapped inside the Fortress at Ravaldino as Borgia’s cannons pound the walls, Dea reviews Caterina’s scandalous past and struggles to understand their joint destiny, while Caterina valiantly tries to fight off Borgia’s unconquerable army.