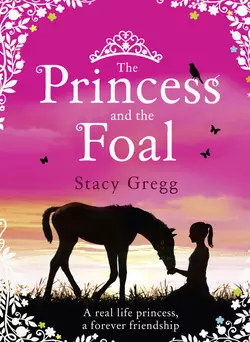

The Princess and the Foal

Stacy Gregg

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Природа и животные

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 536.55 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A novel of heart and courage inspired by the incredible story of a real life princess.Princess Haya, daughter of the King of Jordan, loves her family more than anything. So when tragedy strikes at its heart, she is devastated.The Princess becomes ever more withdrawn until, on her birthday, the King gives her a life-changing present. An incredible new friendship grows and the heartbroken princess begins to dream of an extraordinary future.Inspired by the real-life story of Olympic equestrienne Princess Haya Bint Al Hussein and set against the exotic backdrop of Arabia, this novel is destined to become a modern classic.