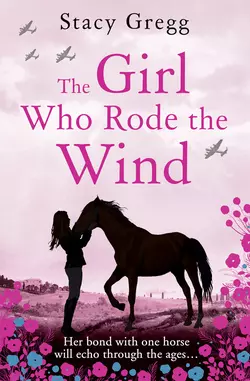

The Girl Who Rode the Wind

Stacy Gregg

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 288.34 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 07.05.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: An epic, emotional story of two girls and their bond with beloved horses, the action sweeping between Italy during the Second World War and present day.When Lola’s grandmother Loretta takes her to Siena, Italy, for the summer, Lola learns about the town’s historic Palio races – a fast and furious event where riders whip around the Piazza del Campo, and are often thrown from their horses while making the treacherous turns. Lola is amazed to learn her grandmother used to take part in these races – and had the nickname ‘The Daredevil’!Nonna Loretta tells Lola that she used to race in a rival team to the boy she loved – who was captured by the Nazis in 1941. Lola develops a bond with a beautiful racehorse. She jumps at the chance to enter the Palio – can she win, in honour of her grandmother? And can she uncover the mystery of the boy’s capture and fate all those years ago?