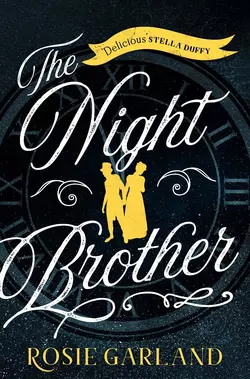

The Night Brother

Rosie Garland

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1040.01 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ‘Echoes of Angela Carter’s more fantastical fiction reverberate through this exuberant tale of a hermaphrodite Jekyll and Hyde figure … enjoyably energetic’ SUNDAY TIMESLate nineteenth-century Manchester is a city of charms and dangers – the perfect playground for young siblings, Edie and Gnome. But as they grow up, they grow apart, and while Gnome revels in the night-time, Edie wakes each morning, exhausted and uneasy, with only a dim memory of the dark hours.Convinced she deserves more than this half-life, she tries to break free from Gnome and forge her own future. But Gnome is always right behind, somehow seeming to know her even better than she knows herself. Edie must choose whether to keep running or to turn and face her fears.The Night Brother is a dazzling and adventurous novel exploring questions of identity, belonging, sexual equality and how well we really know ourselves.