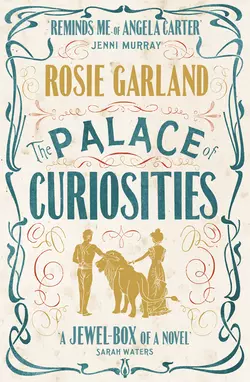

The Palace of Curiosities

Rosie Garland

A luminous and bewitching debut novel that is perfect for fans of Angela Carter. Set in Victorian London, it follows the fortunes of Eve, the Lion-Faced Girl and Abel, the Flayed Man. A magical realism delight.Before Eve is born, her mother goes to the circus. She buys a penny twist of coloured sugar and settles down to watch the heart-stopping main attraction: a lion, billed as a monster from the savage heart of Africa, forged in the heat of a merciless sun. Mama swears she hears the lion sigh, just before it leaps…and when Eve is born, the story goes, she didn’t cry – she meowed and licked her paws.When Abel is pulled from the stinking Thames, the mudlarks are sure he is long dead. As they search his pockets to divvy up the treasure, his eyes crack open and he coughs up a stream of black water. But how has he survived a week in that thick stew of human waste?Cast out by Victorian society, Eve and Abel find succour from an unlikely source. They will become The Lion Faced Girl and The Flayed Man, star performers in Professor Josiah Arroner’s Palace of Curiosities. And there begins a journey that will entwine their fates forever.

THE PALACE OF CURIOSITIES

ROSIE GARLAND

For everyone who believed

I would get here,

even when I didn’t

CONTENTS

Cover (#u53c8f85b-1cb9-5638-b0af-6ff9cf60c956)

Title Page (#u4e701c0b-6e2f-5244-b7d3-7e379916ce17)

Dedication (#u1319dd60-60c3-59d9-a358-9e871103e040)

EVE: London, November 1831 (#u6490d1e6-72a4-5a4c-a3b9-5cf0ff2807ed)

ABEL: London, October 1854 (#ub7378196-9650-5d4b-9df3-97745dd0a980)

EVE: London, November 1845 (#ua9fdda04-75d9-52c2-95dc-9f685a2bc816)

ABEL: London, January 1857 (#uc38b52ab-85c5-5982-8963-0afe41ca7af4)

EVE: London, March–April 1857 (#u635b8ae4-27e9-5f10-8103-356038cda49f)

ABEL: London, May–August 1857 (#litres_trial_promo)

EVE: London, May–July 1857 (#litres_trial_promo)

ABEL: London, August 1857 (#litres_trial_promo)

EVE: London, October 1857 (#litres_trial_promo)

ABEL: London, February–March 1858 (#litres_trial_promo)

EVE: London, June 1858 (#litres_trial_promo)

ABEL: London, September 1858 (#litres_trial_promo)

EVE: London, November 1858 (#litres_trial_promo)

ABEL: London, November 1858 (#litres_trial_promo)

EVE: London, November 1858 and onwards (#litres_trial_promo)

ABEL (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

EVE

London, November 1831

Before I am born, my mother goes to the circus.

She has smelled sweat before: she knows the stink of mouldy cloth, meat left too long, the mess kicked into drains. But tonight, the world is perfumed with fairy tales. She gulps down its promise and a rope tightens across her stomach, causing her to stumble against Bert.

He doesn’t notice. He pulls her up the theatre steps, head turned away, hair sleek black ink. She feels like a princess, even if she is being dragged headlong to the ball. She’s no idiot: she won’t let go of this charming prince come midnight.

Bert pays for them both as if sixpences are a trifle, and bustles her through the crowded foyer so fast the gilded plaster and frosted glass are a blur. She grips his arm above the elbow and he doesn’t push her off. He is a good one: a stopper, a stayer-in. How he will love her! He flings his arm round her shoulders and squeezes her into his buttoned-up jacket.

‘Now, girl,’ he rumbles. ‘Mind how you go.’

He will ask her that very night, she knows: will ask the question she’s been working up to for three months now. She is seized with such a fierce certainty that it makes her dizzy. She does not realise it, but this commotion bubbling through her veins is all in preparation for me. The velvet drumbeat of her heart and the fanfare of her gasps are heralding my arrival. I have never kept an audience waiting.

Bert pushes them to the front row of benches. They are full, so he flaps his hand and the people already seated there shuffle up a little, but not enough. He curls his hand into a fist: they shrink away, and he and Mama sit down.

‘This is the best place,’ he says loudly, although no-one seems about to disagree. ‘I would not sit in the galleries. No, I would not.’

He pauses and stares at my mother.

‘You are right, Bert,’ she says, for an answer is needed.

She gazes up at the tiers of seats climbing the walls towards a roof she can barely pick out in the darkness.

‘Batty’s Amphitheatre is far grander,’ he continues. ‘There is a chandelier with a thousand crystals.’

He is so close she can feel the feather of his breath stir the down on her cheek.

‘Oh?’ she whispers, and it takes a moment for her to realise he is still waiting for a response – a good one. ‘This is marvellous, Bert. All I could want.’

The sun comes out in his face when he smiles. He is as tall as a statue in a park, and certainly as good-looking. But there is no more time to adore her new idol, for a gentleman appears in the circle before them, eyes ringed with black, lips and cheeks rouged.

‘Gentleman!’ he cries. ‘And ladies!’

This creates a swell of merriment, and Mama thinks it best to smile also.

‘Tonight we have mirth!’

A cheer bursts out.

‘Wit!’

Another whoop.

‘And jollity!’

Mama joins in the cheering, and for once no-one tells her to be quiet. The Master of Ceremonies strides about the arena, brandishing his hands.

‘You have come on a very special evening!’ He grins, eyes gleaming. ‘How happy I am to welcome you to this Palace of Delights on such an auspicious occasion! What Luck! What Serendipity! What Felicitous Providence!’

There is a hum of appreciation. Mama wonders why he is stretching his words out so, pulling at them so hard they are in danger of breaking.

‘We humbly offer, for your discernment, Wonders Unparalleled! Incredible Feats of Daring! Please welcome the Italian Fairy, lately arrived from Milan, the Empress of the Air! Signorina Chiarini!’

A storm of clapping breaks over their heads. From the muddy dark of the carved ceiling a rope uncoils, lowering a hoop studded with rubies and emeralds more precious than those kept in the Tower. Balanced there is a magical creature who sparkles even more brightly, thighs bulging with diamond garters, beautiful as a fairy. She waves at my mother, winking at how clever she is to have such a handsome young man on her arm. Mama leans into Bert’s shoulder. My hero, she thinks.

The lady does a swift pirouette, somersaults on to her hands, kicks up her heels and swings backwards and forwards on the golden ring. She strikes pose after impossible pose, accompanied by the gasps and moans of the crowd, for she plays so close to the brink of letting go. The whole time her grin is as broad as the street outside. My mother bites her lip: She smiled at me.

Then the acrobat climbs the rope, hand over glittering hand, wrapping it around her leg and dangling upside down, spinning like a whipped top. She spreads her arms; she falls. Mama is deafened by shrieks of dismay, only to hear them transformed into cheers of astonishment as one ankle is caught in the cord, cleverly twisted. The signorina swings, a gemstone on the end of a chain.

In the intermission, Bert buys her a penny twist of coloured sugar; she licks a finger and sticks it into the sweetness. She remembers she must not appear selfish, and offers him the paper cone, waiting for him to push his finger into the dint she has made. Instead, he grabs her hand, presses his lips around her fingertip and sucks.

‘You’re sweet enough for me,’ he says.

She feels herself colour up like rhubarb and wishes she could be one of those nicely brought-up girls who blush delicately. As she turns to hide her embarrassment, a new lady steps into the light, wearing a tight dress that shows off most of her titties. She sings a song about her sailor boy, and it is a good song, and many voices accompany her during the chorus.

As she trills up and down the scales, a number of low stools are carried out and placed in a circle around her. The painted gentleman appears from the side and bows her off, to whistles and shouts.

‘Ah yes! The Fair Clara!’ he simpers. ‘The Most Dainty of Girls, lately from her Mother!’

The crowd roar once more.

‘Be assured she will return. But now, it is time for stronger meat. Ladies and gentlemen! I require of you to engage your sternest courage! I ask you boldly: are you prepared to be petrified?’

‘Yes,’ they cry.

‘Are there any amongst you of fragile disposition?’

‘No,’ they declare.

‘No cowards?’

‘No!’

‘Brave men and true?’

‘Yes!’

‘Are you stout enough to come to the aid of any delicate creature who may faint and fall gasping into your lap?’

At this, there is howl of laughter Mama does not quite understand.

‘Yes, indeed!’

‘Can you view the most monstrous potentate of the animal kingdom without fear?’

‘Yes, oh yes!’

‘I present to you, brought in at great expense from the Savage Heart of Africa! A Monster Forged in the Heat of a Merciless Sun! Gentlemen! I call upon you now to protect your lady companions!’

‘Hurrah!’

‘Behold then, the Fearsome King of the Beasts, the Ethiopian Sovereign, Djambo! And his Master, that most courageous of men, Mr Edwin Phillips!’

As the crowd applauds, a lion is hauled out on a chain and padlocked to one of the stools. It has been beaten bald as an old carpet. Its face is swiped with ancient scratches and one flank sports a hand’s-breadth of dull pink skin. Mr Phillips cracks the long tail of his whip and Djambo staggers on to the seat. He slashes again, adding a fresh welt to the tip of the great cat’s nose.

‘Ho!’ shouts Mr Phillips.

Djambo yawns. Mama is close enough to hear the lion-tamer hissing, ‘Move, you scabby bastard, or I’ll make a rug out of you.’

Djambo opens his eyes and looks directly at my mother. She feels like a package of pork, wrapped in brown paper. Mr Phillips is sweating. A moustache of dirt creeps across his top lip.

‘Ho, Djambo!’ he cries, bringing down the lash.

Very slowly, the lion moves his gaze from my mother to Mr Phillips.

‘Now! I command you! Jump!’

‘Yeah! Jump, why don’t you!’ bawls someone at the back.

‘Hey, Puss! Didn’t get your saucer of milk this morning?’ chirps another wag, to great amusement.

‘Boo!’ says Bert, and a few pick it up.

The lion ignores them all and opens his mouth wide, gusting Mama with a reeking gale of dead breath. She claps her hand over her nose, but it is too late. Deep in her belly, the clot of blood that will be me in under an hour has smelled it, too. Mr Phillips whispers, ‘Move, for Christ’s sake, or I’m finished,’ and they’re the last words she does hear him say. He lifts his arm, flogging the beast again and again with the leather strap. The straggle of catcalls gains strength.

Mama is sure she hears Djambo sigh, just before he leaps. The chain rattles, tightens, but stretches far enough. The lion peers into the eyes of its torturer, and grins. For a moment the candles around the circle burn as bright as the hot bronze of an African sky; the baying of the audience is translated into the filthy laughter of hyenas. Then Djambo opens his jaws and closes them tight. The hyenas start to scream like women, and the sky flickers back into black.

The lion shakes his head from side to side, and Mr Phillips swings also. Three men with clubs race into the circle and wallop the beast until he lets go of the dying man, who slumps to the floor, a cat-o’-nine-tails of blood spurting from his neck and lashing the air. Djambo turns up his muzzle to catch the crimson rain beating down and lets loose a roar. Mama feels her face speckled with a spray as fine as drizzle. The lion’s cry thunders down her throat; a raging tide of blood carries its essence into her womb and I stir.

She sits quiet, still. She has never felt so calm. But around her, the world is going mad. The mob is on its feet, and everyone’s feet are in the way of everyone else’s; the air is raw with screaming at the sight of a man’s head bitten off. Bert is gone from her side. Mama stands, spies him a way in front of her and panics into movement, afraid of losing him, tonight of all nights. She races after his shining head, bright as a billiard ball on the tide of terrified bodies.

The wave spills her on to the street. She doubles over at the sudden stitch in her stomach as I dig in my claws and take root. She falls on to all fours, fingers squeezing the safety of the gutter muck. Dirt, she knows. Dirt, she understands. But just now she needs something more than dirt, something to swill away this new pain I am causing her. She crawls into a side-alley and hugs the wall, panting.

Bert appears, towering above her. She looks up, wondering how he found her, for it seems a very long time since she saw him last. There is such an uproar at the bottom of her belly, such a storm. He pats her on the back, very gently.

‘Here, girl, here,’ he says. ‘You all right?’

She lurches to her feet, grabs his wrist, pulls him towards her. Now she understands why he is there: she needs him to flush me out.

‘Bert,’ she says. ‘Now, Bert. Do me now.’

He makes a show of pulling away, but his heart quivers. He flicks his eyes left, right, but the alley is empty enough for no-one to take notice.

‘Oh Bert. Help me, Bert.’

She drags his hand up her skirt, points the way up the road he didn’t think to find so easy; she pulls at his buttons and he’s hard already, for doesn’t he know women change their minds in a second? He pokes between her legs and finds the soft ready core of her. They rock me in the cradle of their rutting.

Not that I need the swim of his seed: I am already made. I am nothing to do with him and everything to do with snips and snails and lion’s tails. I hunker down for my nine-month wait. He’s done quickly; looks to see if he read this right but she’s smiling, wider than she’s ever smiled.

‘Oh Bert,’ she says, and will not let go of his hand. Her eyes are inky with pleasure.

‘You all right, Maggie love?’ he says.

‘It was wonderful,’ she sighs, unsure if she means what he has just done to her, or the lion.

ABEL

London, October 1854

Eyes closed. Waking. Hands upon me. Voices swarming into my ears. They start with my pockets, ferreting their fingers deeper and deeper into the ruins of my clothing.

‘Not much here,’ whines the voice of a boy. ‘Not so much as a bloody wipe.’

‘Nothing.’ This sounds like a woman.

‘No use.’ And this, a girl.

‘It was nice, his jacket, but it’s finished.’

‘Waste of bloody time.’ This, another child.

‘Now that’s where you’re wrong,’ says a deeper voice, a man. ‘There’s a good doctor at the hospital as will give a few shillings.’

It seems there is a crowd gathered. I can hear the gentle prowl of the river draining towards the sea. Fingers lift my wrist, let it fall.

‘Doctor? Too late for quacks. He’s stone cold.’

‘He’s not breathing.’

‘He’s a dead one.’

I wonder if I am the dead man they are talking of so freely. My eyes are sticky with some insistent glue, my mouth also. Neither will open.

‘The doctor I know will take a gentleman in any condition, if you get my meaning.’

‘Ooh, that’s not right, George. Not decent.’

‘What’s he to you, all of a sudden?’

At that moment my body chooses to unseal itself: eyes crack open, mouth gapes and I cough black water. They spring away: the corpse they thought I was is suddenly too lively for comfort.

‘He’s alive!’

I vomit again, to prove the truth of it. My vision is unsteady. I am surrounded by vole-faced creatures with yellow teeth, breath hanging before them, the bones of their faces harsh. They are the colour of the mud in which they stand.

‘Not a chance.’

‘Got half the river in him, George.’

‘Enough to fill the Fleet ditch.’

‘He’ll be a stiff soon enough if he’s swallowed any of that.’

‘He’s coming round.’

The man they call George detaches himself from the pack; lowers himself to my side.

‘Give this man his boots back,’ he says.

‘They’re mine,’ whines a skinny boy.

‘Give him his trousers, at least. Can’t have him walking around with his crown jewels up for grabs.’

‘Fuck you.’

‘And your sister.’

Small hands lift me out of the peaceful cushion of slime. I retch with the movement.

‘He stinks.’

‘So do you.’

‘What’s your name, man?’

‘Where are you from?’

‘Pissed, were you?’

My head swims with the need for words, for a mouth to form them, lungs to squeeze air, a tongue to shape the sound. There are so many tasks to perform and it is too much for me. I try a word, drawn up from deep inside the well: it meant a greeting when I used it before. They look from one to the other, raising bony shoulders.

‘What’s he saying?’

‘Don’t ask me. Some wop nonsense,’ says George.

‘What are you trying to say? Say it again.’

I choose a different word. Their eyes remain blank.

‘Still a load of codswallop.’

‘Here. He’s that Italian fellow. That nob as went missing.’

‘Yeah. Look at his eyes.’

‘Jumped off Blackfriars Bridge.’

‘They said he was shouting, raving. Ladies were screaming.’

‘Sank like a stone.’

‘But it was a week ago. A week, in that shit? Can’t be him. Can it?’

‘Rich bloke, I heard. A real swell.’

‘I told you his jacket was nice.’

‘Rich? Ooh. They’ll want him back, then.’

‘They’ll be grateful, like.’

The ring of eyes glitter diamonds. One small creature – male or female, it is hard to say for its hair is a felted mat obscuring the face – raises its paw to touch my face, only to be clouted away. It whimpers, but almost instantly reaches out again, to be smacked off as fiercely.

‘Grateful to them as found him.’

‘Them as saved him,’ corrects George.

I want them to go away and leave me here. I want to worm myself back into the mud and pull its blanket up over my chin. I am filled with the feeling that I have not been dead long enough. I do not know why, but I want to be dead a good while longer.

‘Come on, sir. Say something else.’

I search for sounds to please them. ‘I am drowned,’ I say.

‘What’s he on about?’

‘He says he’s drowned.’

‘That’s English. Doesn’t sound wop to me,’ says George.

‘Well, he looks Italian.’

‘Maybe that’s just dirt.’

‘He’s got to be that rich dago. There’s no money in it if he’s just some English bastard.’

‘Can’t we just say he’s that Italian, George?’

‘Don’t be so bloody stupid.’ The man puts his face close to mine. ‘Who are you, then? Eh?’

‘I don’t know,’ I reply.

‘What’s your name?’

I scrabble for the answer, paddling in the gutter of my mind, turning up nothing. I try harder. It is not a blank wall I come up against: there is no wall, no structure of any kind. I am void, featureless as the thick stew of human waste in which I am lying. They look at each other across my body.

‘He ought to be a goner.’

George snorts, placing his hand upon me. I see a bird made of blue ink flap its wings in the space between his thumb and forefinger.

‘Bird,’ I whisper.

‘He’s a nutter,’ someone laughs.

‘He’s not right,’ is the opinion of another.

‘No one could last a minute in that, let alone a day.’

‘He looks like he’s coming out of the mud.’

‘Like he was buried in it.’

‘He ought to be dead. Why ain’t he?’

‘Something’s not right.’

They begin to shrink back, all but the tattooed man, who regards me with thoughtfulness rather than fear.

‘Come on, George. Leave the likes of him be.’

One of the women throws my trousers back at me; spits.

‘I don’t want nothing of him. Ooh,’ she whinnies. ‘I touched him.’

She wipes a hand on her greasy skirt. The boy holding my boots shifts from sticky foot to sticky foot.

‘I’m keeping these,’ he mutters defiantly.

George grins. ‘Up to you, mate, but I’d not walk one inch in this man’s shoes. He’s not got the decency to die when he should.’

The lad chews the inside of his mouth awhile, and then hurls my boots into the muck.

‘Fuck you, George.’

‘And your sister. Your mother and all. And when I did, they didn’t charge me, neither. Which is not like them in the least.’

George places his mouth close to my ear.

‘Now. You tell George here your little secret. I can spot a queer one when I see it. How come you’re not dead?’

‘I do not know.’

Again, it is the truth. I cough up another mouthful of the river and it dribbles down my chin.

‘Could be worth your while. And mine.’ His eyes gleam like sovereigns. ‘I think you’ll be coming with me, Lazarus.’

He grasps my hand, winches me into a sitting position. I heave, spill more oily slops down my chest. It seems I cannot stop leaking.

‘Ooh,’ squeals a girl from her safe distance. ‘George is touching him.’

The words do not make George let go. I look at the way his fingers clasp mine, the ruddy glow of them against the bleached grey of my sodden flesh.

‘I should be dead,’ I whisper. ‘Why am I not so?’

‘That’s what I’m going to find out, Mr Lazarus,’ says George, showing me two rows of even teeth.

‘What’s he saying?’ calls out one of the mudlarks.

‘Nothing you lot need to know. This is man’s business.’

‘Talking up horrors, that’s what they’re doing,’ wails a female voice.

The clacking of a rattle winds its way into the space between my ears.

‘Fuck me, it’s the Peelers.’

‘Stay where you are,’ yells George. ‘We’re breaking no bloody laws.’

‘When did they ever care about the law?’

‘Stay if you want. I’m legging it,’ says the boy who gave up my boots.

I hear the suck and slather of mud as they hurry off. George looks from me to their retreating backs to me again. The rattling grows louder. He chews his lips.

‘Fuck. Fuck. Fuck. Fuck the Queen and her fucking consort too.’

He lets go of my hand and I fall back. I stare at the sky. My thumbs dig into the soft quilt of the filthy ooze, and I let myself slide into the comfort of its tight wet mouth. I am lullabied into a drowse by the slurp of their footsteps retreating, the moist tread of other men approaching.

EVE

London, November 1845

They say when I was born I didn’t cry; I meowed and licked my paws. They say that the midwife dropped dead of fright. They told a lot of tall stories but none of them were as tall as the ones I told myself when I looked in the mirror. Mama said I shouldn’t look in mirrors: it would upset me. What she meant was, it upset her.

Other girls look in the mirror and see the fairest of them all. I saw a friend. Her name was Donkey-Skin. I can’t remember when she came to me, only that she was always there. My only companion, born of imagination and loneliness, which is a hectic brew for a child. What did it signify if no one else could see her? I liked it so. She was mine and mine alone.

I did not want to share her with another soul, so I kept our conversations whispered, our games quiet. When Mama asked me whom I was talking to, I said, ‘No one!’ in my most innocent voice. She took it for another sign of my strangeness and it was not long before she ignored my chattering. Donkey-Skin wove herself from all the things I hid from my mother, knitting herself from the truths Mama would not tell me but I found out anyway.

Donkey-Skin was ugly: even uglier than me, which was quite something. If I was hairy, then she was as furry as a cave full of bears. If I was a freak, she was a cursed abomination in the sight of God. If I was lonely, she was abandoned on a hillside for wolves to devour. She was different because she did not care. Her life’s work was to teach me not to care either.

When we were alone she murmured, Kitten, kitten, my very own pet. Her lullabies rang over the terrifying stretches of the night as I rested my cheek on her breast, safe under the press of her arm. She loved me because of my thick pelt of fur rather than despite it. Only she could sort my tangles. I purred beneath her gentle comb as she groomed my baby hair.

Of course, Mama was having none of that. Every day she reminded me that God made me foul-featured for a reason: punishment for a sin I could not remember and she never revealed. It could have been so much worse, she said. I was lucky, she said. Was I beaten? No. Was I fed? Yes. I had a roof over my head; I had a mother who was respectable. I should bow my head, keep my eyes down, keep the peace, be sweet, be grateful that someone cared enough to put bread in my mouth. I could have been sold to trim fur collars or made into a muff. I could have been tied in a bag and dropped in the Fleet.

My earliest memory is of Mama shaving me. She sat me upon the table and I kicked out my heels. She caught my foot and kissed the only part of me that was smooth and counted out my toes: ‘This little piggy went to market, this little piggy got shaved.’ Or was it ‘saved’? I do not remember. Her songs were hopeful spells to make the fairies take pity and return the pretty pink and white babe they’d stolen from her womb. There was no escaping the truth of it. I was a changeling and as furry as a cat.

She doesn’t want a baby, Donkey-Skin whispered in my ear. She wants a piglet.

I giggled.

A naked pink wobble of a thing, with that sore scalded look of them, tiptoeing as though the ground hurts and makes them screw up their eyes.

You are not a piglet, said Donkey-Skin. Don’t be one, not for anyone.

Donkey-Skin was right; I did not want to be a piglet. Piglets grew into pigs, fat overblown pillows slathering in their own muck. Pigs were dinner. I had no wish to be sliced, smoked, fried, salted, stewed or pickled.

Mama grasped the kettle and heaved it from the mouth of the range, poured a bowlful and soaked the dishcloth. A cowlick of steam curled off the face of the liquid. She folded the rag in half and hung its hot wet curtain across my face.

‘Mama?’ I whimpered. ‘Mama?’

‘Is it too hot, little one?’ she said.

She pulled the flannel away and I tingled with the sudden cold. I grabbed at it, but my reach was far too short. She picked up a jug, took the brush, dipped in the bristles and swiped foam across my cheek. I giggled and wiped it away, slapping the white mess on to the floor.

‘No,’ she said and sopped my other cheek.

I wiped that away also, squeaking with delight.

‘Stop it,’ she said, louder, and I squealed louder, to match her.

She aimed quick blobs at my chin, my cheek, my forehead. I could not get enough of this new game. Even when she held my wrists with one hand and soaped my face with the other, I wriggled free.

‘I am making you beautiful,’ she snapped, and started to cry. ‘I’m doing this because I love you.’

Then she smacked me. I had been stung far harder in the past, and deserved it too. This small slap spelled me into stone.

‘Stay very, very still.’

I sat obediently and let her lather up my whole face and neck. She unfolded the razor, stropped it keen and laid it on my forehead. I quivered under its chilly stroke, stranger than the licking of a cat. The blade came away loaded with scum, and more. With each scrape the water grew dirtier, clogged with brown silky threads which collected in thick clots. I grew cold. When she finished, she kissed me and tickled my hairless chin.

‘Now you’re my pretty girl, my real girl, the girl I should have got, the one who loves her mama and will never leave her side.’

That night, Donkey-Skin visited me as I undressed for sleep.

‘Mama’s made me pretty,’ I sang, spinning in a circle to show off my new nakedness.

Pretty? she snorted. She’s made you ordinary.

‘Mama told me I am a real girl now. It must be true.’

You look like all the rest of them: simpering, feeble, wet-wristed, snickery-whickery, snappy-snippy little girls made of milk and money.

‘Then what is a real girl, Donkey-Skin?’

It’s a long story. I have plenty of answers. We have time.

Every week Mama shaved me. When I was old enough, I said no. She did it anyway. I grew and still she shaved me naked, until I was tall enough to smack the razor from her hand.

‘You’ll look like an animal,’ she wept. ‘Is that what you want?’

I stood in front of the looking-glass and admired myself. My moustache wormed across my lip, the tips lost in the crease behind my ears. My eyebrows met over the bridge of my nose and spread like wings up the side of my forehead. My chin sprouted a beard the colour of combed flax, reaching to my little breasts.

You are my very own princess stuck in the tower, whispered Donkey-Skin.

I laughed. ‘A very small tower!’

Donkey-Skin tugged my moustache.

I will spin you into gold. Weave a happy ending with a handsome prince …

‘I will weave my own story,’ I replied, and she smiled.

‘Listen to you talking to yourself!’ cried Mama. She wiped her nose. ‘Look at you,’ she sneered. ‘You’re not even human.’

I stuck out my chin and my beard swung backwards and forwards.

‘I know that I am different. How could I not? If God intended me to be this hairy, I shall find out the reason, however long it takes me.’

‘Do you think this is a game? You’re only safe out there on the streets because I make you look like a real girl.’

I crossed my arms.

‘People know who I am. Whatever I look like, they’ll say, There goes Eve, Maggie’s daughter.’

‘You are stupider than you look. And you look particularly stupid. Can’t you see my way is better?’

‘I shall prove you wrong,’ I said. ‘Today, I shall take the air.’

I opened the door and stepped into fog as thick as oatmeal. Dim hulks of buildings swam towards me as I strolled along the pavement. No one pointed at me. Shadows tiptoed past, hands on the wall like blind beggars, and at first I was comforted by the thought that I was walking unseen, and therefore in safety. This soon changed to frustration: I would have no proof that our neighbours did not care what I looked like. I wanted to show Mama that I could be seen and accepted.

I kept walking, picking my way carefully, and did not realise how far I had come until the gate of the Zoological Gardens gaped before me. I strode past the ticket office, and smiled at saving sixpence. The mist had cleared a little and I found myself in front of the lion’s cage. The great cat lolled within. A raven pecked at its beard.

The dark form of a man appeared next to me. He lifted his arm and threw a stone at the lion. It bounced off the animal’s head.

‘Oh, Harold, don’t carry on so,’ said a woman’s voice.

His answer was to throw another.

‘Oh, Harold,’ she simpered.

A small crowd began to gather. More stones were thrown, until the lion was surrounded by a ring of pebbles. It continued to ignore us. Then a boy spotted me.

‘Hey, look!’ he squealed. ‘Look at that, will you!’

Every nose swivelled to follow the compass point of his finger. There was a pause. I smiled. What better place to prove I was no animal than here, where the dividing line was drawn so clearly? They were in cages, and I was not. The mist grew thinner. I held my breath as it peeled away.

‘Oh, Lord, will you look at that,’ said the first of them.

‘That’s not right.’

‘It’s not decent.’

‘If that were mine I’d never let it out.’

‘If that were mine, I’ve never of had it, if you get my meaning.’

Their eyes poked knitting needles at me. I took a step backwards and felt the bars of the cage.

‘Shouldn’t be allowed out. Should hide itself away from decent folk.’

‘Mind you,’ chirped one wag, ‘right place for it, ain’t it? You know, the zoo, like,’ he said, in case they missed the joke.

They did not. There was a rattling of unpleasant laughter.

‘Here, monkey. You a monkey or what?’

‘Even a monkey ain’t that hairy.’

‘It’s a dog.’

‘Nah. Dog is man’s best friend. It ain’t no friend of mine.’

‘Perhaps it’s an exhibit got out of its cage.’

‘Can’t see no park-keepers,’ one growled.

There was another pause as they ran out of amusing things to say. A boy bent down, picked up a stone and let it fly in my direction. It was weakly thrown and wide of the mark, in that way of first stones. I waited to see if anyone would tell him off. No-one spoke. In their eyes I read drowned cats, kicked dogs, rabbits skinned alive. I saw my own pelt stripped off and spread like a rug before the kitchen fire.

There was no point in searching for escape. The moment I looked away I would be piled up with rocks high as a hill. The cage pressed its bars into my back, too narrow to slip through. Then I felt the sweltering breath of the lion on my neck. I waited for its claws to rake me open, but instead my skin was sandpapered with a tongue the size of my foot.

‘Look! Even the bloody lion thinks it’s a cub!’

‘Freak!’

The stones had started as a drizzle, but now turned to rain, bouncing off the bars. One hit the lion on the face, and its roar boomed like thunder over the heads of the mob, which turned and ran. I reached into its prison and scratched the top of its head. A purr rumbled in its throat. A man in a peaked cap came running up to the enclosure.

‘You bothering my lion?’ he panted; then he saw my face and stepped away. ‘Oh. Sorry, miss.’

‘I won’t bite you,’ I said, but he muttered an excuse and left.

I did not cry. I would not shed tears. I took myself back home bent double with my shawl tied round my head. Mama did not say a word, but she smiled for the first time in many months.

Donkey-Skin was my only comfort. She called me all the names they shouted; all the cruelties made of words. Hours and hours we played the game; for days, for weeks, for years; until the words were mine again, and I was not just bitch, but the queen of all the bitches: not just freak, but empress of all the freakish, with a dazzling crown.

She told me new stories: of a prince clever enough to spot a princess through her wrapper of dirt, who would kiss the beast to make it beautiful. A fearless man who would fight through the bramble forest a hundred years’ thick, past the wolf at the door and the witch at the gate. My fur was my protection. Only the most true of heart would find their way through.

There is a man for you with knife in hand to cut through the world’s binding. A man of blood and flesh and bone and strange in all of them.

Keep an eye out for him. Watch carefully. You may not know him when he appears.

I am Donkey-Skin. Peel away this fur and I am as pink as you. The blood in my veins is as crimson. If you flay me, we stand equal. Beauty is truly skin-deep. We are all horrors under the skin.

ABEL

London, January 1857

It’s not like waking up. I’m awake already. I have been somewhere. Like sleep, but not. My body rocks backwards and forwards. Something has hold of my shoulder and is shaking it, vigorously.

‘Wake up, Abel,’ a voice whispers. ‘It is time.’

‘Time?’ I ask, and forget everything.

I open my eyes. The first things I see are blocks of grey. They move: to and fro, up and down, side to side. A dark column hovers before me and I hold my breath. It leans over my bed, a swirl of mixed brightnesses. It touches my arm, and speaks.

‘Wake up. Are you awake?’

With the words, the ghost becomes a man.

I answer, ‘Yes.’

The smell of dried blood is on his shirt, under his fingernails, on the soles of his boots. I know this smell, for I have it on myself.

‘It is time for work. Come now.’

I look about me, and see blotched and crumbling plaster above my head. Narrow slots pierce one wall close to the ceiling, letting in a dribble of pale light. I am surrounded by a multitude of pallets, packed close together. The spectres rising from them become other men. I inhale the comforting stink of my own body and the warm reek of the others crowded into this place; a morning chorus of belching, hacking, spitting and farting giddies me with happiness. I remember: I sleep here. It is my home.

‘Shift yourself, Abel. You’re like this every morning.’

His name will come to me in a moment. The man waking me works with blood. I sniff again: animal blood. Meat. A butcher? No, a butcher has his own business, and does not need to sleep in a cellar. Then I know: he is a slaughter-man. We work together. This reasoning takes very little time, but he is impatient.

‘Abel, get bloody moving.’

It is my name. This man is my friend.

‘Yes, yes,’ I say cheerfully.

‘You’re in a good mood. Move, you old bastard.’

I am already dressed in most of my clothes. All I need do is put on my cap and boots. I get them from under my head, where I have been using them as a pillow. My friend pats me on the shoulder and smiles. We climb the grimy steps out of our cellar and join the troop of men lining up to pay the tally-man, who leans against the door-jamb, book in one hand, pint bottle of tea in the other, and a stub of a pencil behind his ear. Many of our companions thumb their caps and promise to cough up that evening. But we pay our sixpence on the spot for the next night’s lodging as we leave, and I recall that we do this each morning, at my friend’s insistence.

‘We must pay one night at a time. A man never knows what might happen,’ he says.

The moment the words come out of his mouth his name comes back to me, making me suddenly joyful at the gift of remembrance, at the realisation that he returns me to myself thus every day.

‘Alfred,’ I say. ‘You are my friend.’

He laughs and calls me an old bastard once more.

We step out on to the street and my breath catches at each new sight, which stops being new the moment I look at it. I wonder how I would find myself in this blur of grey and brown if it were not for Alfred, shaking me into wakefulness, striding at my side, half a pace in front, urging me on, drawing me out of my drowse and into a beginning of myself.

The world reveals itself to me piecemeal: the flat surface at my side becomes a long terrace of filthy brickwork interrupted by black holes, which resolve themselves into doors and windows. One of these doors leads to my cellar. I gape at how similar it is to all the others, how simple a thing it would be to confuse one door with another. I lose myself in the contemplation of this wondrous revelation and Alfred grasps my elbow, steering me away from the ordure running down the middle of the street.

‘What would you do without me?’ he says.

‘I do not know.’

I blink at this new world, which of course is the same world as yesterday, only somehow mislaid by me overnight.

‘You’d walk through shit the whole time, that’s for sure!’ He laughs, and I understand that it is a joke, and that he does not realise what he means to me. I feel an urge to thank him, but I do not.

At this early hour the rough sleepers are still piled up in doorways, wrapped around each together against the chill. But Alfred and I are different: we are men of purpose. Men like us stride swiftly to a rightful place of employment. We have work to attend to, work that directs our hands and steers our feet, that fills our bellies with food and drink, that shakes us awake and tires us so we sleep deeply; work that gives us the money to pay for a place that is warm and comradely, a place where one man shares his good fortune with another, and where Alfred and I are often the men with that good fortune, for the pieces of meat that we bring.

Work prompts me with a purpose, with something to remember every morning. Without work I would be empty. I shake my head, and with it that unpleasant notion; I am not empty. I have work, I have food, I have lodging, I have Alfred. I am a happy man. There is no more contentment for which I could ask.

A coal-train heaves itself across the viaduct and we pass beneath, the vaulted arches shuddering a rain of soot on our heads, which Alfred dusts from my shoulders with many jokes about how I look even more like a gyppo when I’m blackened with smuts. The first criers are about, shouting, ‘Milk! Watercress! Hot bread!’ Carts jolt past, the iron clanging of their wheels dinning in my ears, bringing me further back into the glove of my senses. We cross over a stream of raw sewage.

‘I don’t know how you manage it. The smell,’ says Alfred, voice muffled by the kerchief he has clapped over his mouth. ‘What are you about? Make haste.’

I pause and look down at the mess. Not a whit of movement.

‘It does not trouble me,’ I say.

‘Now I know you are lying,’ he replies, uncovering his mouth when we are clear of the sewer.

But I am not. It is an aroma, that is all. I stand a while longer, but then realise that Alfred is no longer by my side. I glance down to see what my feet are about, and they are still when they should be moving. I have been looking down too long; when I look up Alfred has drawn some distance away. I command my feet to pick up their pace and keep up with him, for his legs are transporting him very swiftly, his body slipping neatly between the other men passing to and fro along the thoroughfare. I quicken my pace and after some shoving I draw level.

‘You not awake yet, Abel?’ he says. ‘Come now, buck up, or there’ll be no time to eat.’

My mouth waters at the thought of food.

‘Ha! That’s put a spring in your step! Sprightly, now.’

We bound forward. With each stride, I am bolder and the world takes on more solid form. Each step breathes fire into my legs; the flagstones thump back at my heels, prickling my skin with wakefulness; my liver and lights quiver with the blood pumping around my veins. The jostling and jarring of the passers-by returns the awareness of my arms and ribs; the screaming of this waking city brings back my ears. I smile at every assault, for each serves to remind me of my flesh, my meat, my muscle, bone and blood. I am a man again, not the phantom I was upon waking.

A boy passing to my right shrieks the news so piercingly I clench my teeth: ‘Savage Murder! Shocking Discovery!’Alfred sees my grimace.

‘You all right?’

I nod.

‘Loud, isn’t he?’

I nod again. ‘I am very hungry,’ I say.

‘Ah! A fine suggestion.’

He claps his hands together in the cold. We stop at a stall, which I know is the place we usually take our breakfast, and the man shouts his halloa, handing us fat bacon wrapped in a square of dirty bread; a pint of tea each. I shove all into my mouth, and Alfred laughs.

‘Your stomach, the great pit!’

The vendor roars at the joke. I smile through my bread, spilling some, filling them with even more merriment.

‘You will make yourself sick, you silly bastard,’ says Alfred. ‘Yes, we must hurry, but not that much.’

It occurs to me that I am never sick, but I do not say as much. It comes to me that I have tried to explain this before; but such things confuse him, and confusion takes away his cheerfulness. So I continue to play the fool, and he is happy. The grease sticks to my chin and I wipe it off, licking my fingers.

‘Good stuff?’ says Alfred through his bread.

‘Good stuff,’ I reply.

‘That’s you fixed up.’

Right away I know he is speaking the plain truth. The sticky bacon weighs me down into the earth. I pat my chest, feeling the smoke of the chimneys clogging each breath; rub my belly, testing the ballast of the half-loaf within.

‘Thank you,’ I say to him. ‘You are my friend.’

For a moment, his face changes, and I recognise the look. Suddenly I am aware that I have seen it before, over and over. How I know this I do not recall, nor who has looked at me thus: only that many have. I search for names and faces, but find none. It is most confusing. Alfred pushes the last of his bacon between his lips and is once again my gruff companion.

‘It’s only breakfast,’ he grunts. ‘Any pal would do the same.’

The day is no warmer when we hand back the tin mugs; indeed, it is still dark, but I no longer care for I am hot inside. We bow into the wind and head past the tannery and turn left. As we walk through the gate a church clock somewhere begins to strike the hour. I count five.

‘It is the best part of the day,’ Alfred says. ‘And winter too: the best time of year for men like ourselves.’

We strap on our leather aprons, and are ready. I know why I am here. I am a slaughter-man.

The first bullock of the morning is brought in. It is barely through the rectangle of the door before Alfred lifts his hammer and strikes the blow. The eyes roll and it falls forward on to its chin, grey tongue flopping between its teeth, gentle eye dim between the stiff, gummed lashes. Alfred shouts a brief huzzah at such a clean start and grins.

‘Barely twitching!’ he exclaims.

Two fellows hook the hind legs and winch the carcase upwards. Their names have not yet returned to my recollection, though I should have them before another hour has passed. I grasp the soft, warm ear and strike the knife beneath it; blood pours.

‘He never misses,’ mumbles one of the winchers, still chewing on his breakfast, a piece of bread clamped between his teeth.

His name surfaces in the mud of my mind.

‘Yes, William,’ I agree, pleased with myself.

‘There is a man at peace with his labour,’ says Alfred, and smiles. ‘I can see William snoring in long, untroubled sleep. Can’t you?’ He looks slantwise at me. A blade scrapes against bone. ‘Just like us, eh, Abel? You’re not disturbed by what you see here. Are you?’

‘Me? No.’

‘Good. Me neither. Steady hands and a steady stomach. That’s the two of us.’

The beast starts to kick, and Alfred frowns, but it is only a brief show. I raise the blade and watch it fall, guided by a precision I possess without knowing how as it strikes the exact midline of the belly and splits it open; the insides begin to cascade out in a sodden fall.

William and his companion heave out the innards, briefly sorting through the coils for any obvious signs of sickness. They are quickly satisfied, and I slice away the heart, liver and lights, giving a final grunt of exertion as my blade breaks through the cartilage between the vertebrae. The skinners set to work straight away. Three lads carry away the pluck; four others slop the black waters away continuously, bent into their work, never looking up to see whence comes the thick dark stuff they push into the grille of the drain.

I delight in the handsome geometry of the beast: the soft handshake of the intestines coiling about my arms, humid from the belly, delicate green and blue; the perfect smoothness of the liver; the pink and grey lungs, matched in wonderful symmetry and nesting the heart between. There is no time to ponder each marvel, for we have many beeves to work through.

‘This is a hungry city,’ says Alfred.

Each carcase I split open reveals the same beautiful workings, each with their particular differences: a larger pair of lungs; a surprisingly violet twist of gut. But these small variations only seem to further underline the natural majesty of them all; I cannot avoid the sensation that I am close to some revelation about myself. Why the mysterious insides of beasts should make me feel thus I do not know, but they draw me with an uncanny power that here I might solve some riddle. I push towards the answer: I am a man who knows the mystery of beasts.

I see the way they come in after hours of stamping down a hard road: their ankles gone, hooves raw; driven, beaten, thrashed and pushed towards their deaths – and any man who says a beast doesn’t know it is a fool. No fellow-beast comes back from the killing to tell them, but they guess it true enough.

They smell it on the road. Keeping their heads low: not sniffing for grass to chew, but getting a sniff of those who passed before, the excruciating spoor of that last drive, the screaming muscle, the aching bones. Most of all they smell the fear.

And if they are bad on the road in, that is nothing to how they are when they get to the yard and are left standing, listening to the sharpening of blades. They smell death before it happens; hear the thump of the stunning blow before it cracks the first skull of the day; taste the blood of their brothers misting the air from the day before, when their guts spilled out of the bag of their bellies.

The fear of beasts. It is a fire that runs between them dry as tinder. When they get it in them the worst things happen. So I strive to make it quick. Today, we are unlucky.

Alfred raises his hammer with a good will, but when it falls some agency turns it awry and it falls to one side, a feather’s width only, but enough to inflict pain without release. The bullock rears up, its skull caved in. How can a dead animal leap up? When they are hammered, that should be an end to it. But I’ve seen what I’ve seen. Slaughter-men know these things.

It pauses, hanging in the air. We are fixed also, though we must clear out of its way for the plunge that will follow: it wants to take us into that animal darkness, and Heaven help anyone in the way when it comes crashing down. I have seen a man lose an arm, torn off at the shoulder by those fiendish hooves, and heard the beast give a last moan of delight to hear its murderer scream.

It falls, staggering. Alfred tries a second blow, but it swings its head despite our attempts to hold it steady, and this blow is worse than the first, breaking the bone beneath the eyes. The screaming starts: a sound no-one would believe who had not heard it. Women have it when they push a child out of them; beasts have it when we push the life out of them, and do it badly.

It is dead enough to fall to its knees, undead enough to thrash out when the hooks dig through its tendons and the hauling starts, so it takes four men to get it up there, the four who should be mopping the floor, so now we are slipping in the bile it has spewed up. I cut its throat right across, more than is needed, to sever the windpipe as well as the vein, and air whistles out, but at least it is a hiss and not the awful keening.

Finally, we tie it off: heels up, head down, tongue licking the floor; and still struggling. The blade is in my hand. My fellows are getting angrier, and I am the only one who can do a thing about it. I lift my hand; the blade falls and I have some comfort that this stroke at least is deep and true. I lose myself in the sight of its guts, gushing out in a smooth clean tumble. I do not let myself see its juddering terror as I kill it for the last time. I will not let myself think of that at all.

The hauliers are bringing up the next beast, shouting, ‘Get a move on, you fuckers. How long does it take to kill a bullock, for Christ’s sake?’Their charge is restless: it can smell and hear and taste and see what is before it, and knows its share. Then it is in, stamping out its complaint, and we must continue. I look at Alfred: he is sweating, his hand unsteady. The haulers hate him, the winch-men hate him, the sweepers hate him, the animals hate him. His day is already bad, and the only direction it can go is to the worse.

‘Alfred,’ I say.

I hold out my hand and he places the hammer into my grasp. The bullock looks at me with wet brown eyes, and I look back; I lay my hand on its flank until it grows still. Then it happens: it stumbles forwards, as though kneeling in prayer. I am to be its killer, but I am kind, each blow struck by me being on the mark. It knows it will be fully dead when it is split open. I am the only one it can be certain of. Other men try but I succeed, every time. It closes its eyes, knowing I will be quick and sure. It is my nature.

I do not disappoint: neither the beast nor my companions. They see my kindness, and each of them pauses, even the most brutish of the hauliers, and breathe out their relief.

‘You’re a good man,’ says Alfred, and rubs my shoulder, swabbing it with blood.

His voice snaps in the middle, dry and thin. I return the hammer to him.

The day swims past, and I drift upon its languorous current. My arm continues to rise and fall and I am drawn into a drowse by the movement, by the length and silkiness of black hair flowing in a stream from wrist to elbow, the veins standing out along the length.

With each fall of the blade the muscles of my hand and thumb stiffen and relax, and I find myself thinking how simple a thing it would be to make a vertical incision upwards from the wrist; how soft the curtains of skin as I part them, warm as the inside of a mouth, revealing the workings of the body within.

I see myself slip a flat-bladed knife beneath the musculus coracobrachialis and biceps brachii – for these notations are suddenly known to me – and raise them slightly from their accustomed bed against the bone of my upper arm. I do not want to fix my gaze anywhere but on this work, which terrifies me yet is familiar, and comforting in its familiarity.

I am opened up, and am possessed of a knowledge that sparkles through me. My heart soars: I know this. For what are men but hills, swamps, sinkholes, deep abysses, flat plains? I understand now. This is no gazetteer of any country; it is the terrain of man’s interior geography, and I am a geographer of that body for I know the mountains and rivers, the highways and cities. I gaze at my flesh, opened up so beautifully. It prickles, quickens. I behold the mappa mundi. All I need to know is here.

I feel wetness on my cheeks, hear a cough and the softness flies away, as though I have been roughly shaken from sleep. My heart beats fast, and I am filled with a fear that I shall find everyone looking at me, somehow knowing my strange imaginings, but the sound is one of the sweepers. I examine my arm: it is untouched. My body is quiet again.

I shake my head and empty it of what I have just witnessed. I do not know whence it came. I have been affected by the terrified beast earlier, that is all. I am a plain man and do not know such long words, nor such an overwhelming philosophy. It is nothing. I press my knowledge into a deep well.

At mid-morning my companions lay down their tools and go out for a mug of tea and piece of bread.

‘I shall stay,’ I say, for I desire a peaceful spot in which to gather up my ragged thoughts.

‘Come now, Abel. You’ve earned a breather.’ Alfred grins.

‘You more than any of us bastards,’ adds William, and they laugh.

‘One-Blow Abel, that’s you!’

I make my mouth smile also.

‘There is but one carcase needs finishing off,’ I say, lightening my voice to make it careless.

Alfred dawdles.

‘I shall stay also. We shall follow presently.’

He grins at me as they depart.

‘Just the two of us, eh? Best company a man could have.’

I set myself back to work, striking the carcase before me; but my hand trembles and I only split it halfway. I try again and strike untrue, jarring the bone so hard my shoulder numbs, and I drop the axe. The steel rings against stone, and Alfred calls out.

‘Abel?’

‘Yes,’ I reply.

‘What is it?’

‘I have dropped my blade.’

‘Dropped it?’ His voice sounds with shock, and he pushes through the curtain of cadavers to my side. ‘What ails you, Abel?’

His eyes search mine.

I shrug. ‘It is nothing.’

‘Well, then,’ he says. ‘Very well.’

He coughs, busying himself in picking up my blade and placing it into my hand.

‘See,’ I say. ‘I am steady again.’

I make another stroke to prove my words, but it is a poor effort, shearing away and striking my forearm, and I am sliced to the bone. For an instant, all is peaceful as we stare at my arm, the dark crimson of muscle within. He speaks first.

‘Christ, your arm.’

‘Yes,’ I say.

It is true. It is my arm. He, like me, can see the sick whiteness showing at the heart of the slit. I should be afraid, but I am not; I feel no panic as I watch the wound fill with sluggish blood. I wait for it to commence pumping, in the way that kine do when I cut their throats, but it does not. The liquid rises partway to the brim and then pauses, small bubbles winking on the surface. As I watch, I am aware of another sensation: my soul begins to beat sluggish wings, unfolding them after a long sleep. My body tingles, stirs.

‘Christ,’ says Alfred. ‘Dear, sweet Christ.’

He sits upon the floor, not caring about the stickiness and filth.

‘Sit down, man,’ he croaks.

‘Yes,’ I say, lowering myself to sit next to him.

He is trembling.

‘You are dying. You will die. What am I to do?’ he stutters. ‘You will bleed to death. You are slain. What can we do?’ His hands patter all over his apron, wringing the corners. ‘I must get help,’ he says, but does not move.

‘Yes,’ I agree, and do not move either, for my eyes will not leave the sight of my inner workings revealed in this impossible fashion.

I am surprised, but not in that way of a new thing, a never-before-seen thing. It is the stillness of curiosity. I ache to dip my thumb into the dish of the wound to see if I am warm or cool; indeed, I lift my hand to do so, and only hesitate because Alfred is shaking violently, small sobs coming from deep within his chest.

‘I must go. I must go and find a doctor,’ he says, over and over, not stirring. ‘I should not have spoken to you. I distracted you. This is my fault.’

I want to say, It is not, but I am lost in contemplation of this phenomenon.

‘I am not bleeding,’ I muse, and find I have spoken aloud.

Alfred is sitting quite still. ‘Dear Christ,’ he breathes. ‘You are not.’

It is the truth. The injury is full of blood, but is not spilling over.

‘I wonder why,’ I say, for it holds me in a fascination.

I am a slaughter-man: I know well the fountaining of heart’s-blood when an artery is severed.

‘Sweet Jesus,’ repeats Alfred. ‘Look.’

I look. The blood is sinking, and as it subsides the edges of the wound begin to close together very slowly, but fast enough that it is possible to observe the motion. I am held in the grip of a terrific stillness, so entrancing is the sight of my body re-sealing itself. After minutes I forget to count all that can be seen is a red seam along my forearm. I flex my fingers, and they move: I can bend easily at the elbow. Nothing is damaged. Alfred gets to his feet, staggering backwards.

‘You …’ he says, his eyes wild. ‘When a man is cut, he should stay open. You close up. It is not right. You should be dead.’

His gaze darts up and down and from side to side; everywhere but at me.

‘I am not,’ I say simply.

His breathing is rough. ‘I do not—’ he begins, and stops. ‘I do not know you.’

He walks away. I inspect my miraculous arm, twisting it about and watching the line where I cut myself grow smooth and pink. After a while I pick up my axe and continue with my labours. I am determined to concentrate, for I do not wish to slip into another bout of this dangerous half-sleep. The others come back in; Alfred also, but he says nothing, and will not look at me.

I set my teeth and apply myself to my labour. I am a slaughter-man, I say to myself. I cut open the bodies of beasts. They stay open. I was cut, and I closed up. I did not bleed. I shake the troubling thoughts away. I must have been mistaken: I cannot have cut myself so deeply. These things are not possible.

The remainder of the day is simpler. Each beast waits patiently in line, and the greatest noise we hear is the sigh of each giving up its spirit gladly. At the end of the day, I walk out of the gate to find Alfred waiting.

‘Let’s be walking home, then,’ he says grudgingly.

He keeps half a pace ahead of me, and looks back every now and then, as though expecting something, eyes sliding to my forearm. I wince with the knowledge of my body and how it healed; and how he witnessed it happening.

‘Alfred?’

‘What?’ he growls.

‘You are my friend,’ I mumble.

‘Yes, yes,’ he mutters. ‘So you keep saying. Give it a rest.’

He thrusts his eyes ahead, walking faster so that I have to quicken my step to keep up with him. I chew the inside of my mouth until I taste iron. I hold out the package I have been given as my day’s perk: I bear the prize of an entire head, brains and all, for the way I turned things round, the gaffer said.

‘I like brains,’ I say. ‘Brains are tasty.’

He breathes out, slowing down so that I do not have to rush so.

‘They are,’ he agrees, and we fall back into step.

The evening is chilly: he is wrapped up in his coat like a boatman, breath standing before him, humming some tune I do not recognise. I try not to interrupt him. It is difficult. At last I speak.

‘About today—’ I start.

‘It is of no consequence,’ he snaps, picking up the pace again.

‘But it was—’

‘It was nothing!’ he cries. ‘It was a difficult day. That bullock! God, how it wouldn’t die! Enough to make any man see things.’

‘But, Alfred, at the slaughter-house—’

‘I do not want to talk about it. In fact, I remember nothing.’

‘Alfred—’

‘I said, I do not want to talk about it. Get a move on,’ he grunts. ‘It is time to get some food inside us.’

‘Oh.’

My mouth fills with water.

‘That’s the job. Think of that. Nothing else.’

‘Yes. You are right.’

He breathes out heavily, clouding the air around his head.

‘Of course I am. No more rambling. I’m freezing. Let’s get back and get this lot cooked. Of a sudden I have a powerful hunger upon me. Think how good it’ll taste. Any meat you’ve had a hand in is a clean and cheerful dish.’

He slaps my shoulder. I know that the events of today have brought me close to grasping something, but it is already beginning to slip away. If he would talk to me, maybe I could fix my understanding. But he will not.

We walk in silence to our lodging house, a narrow squeeze of a building caught between the muscular shoulders of the tenements to each side. Ours is little different, except the bricks are perhaps grimier, the steps to our cellar a little more slippery with spilt beer and bacon fat, the straw in our palliasses a little older. But there are just as many folk squeezed into the upper floors – three families to a room as I hear it. Their babies squall as lustily; their men and women argue just as cantankerously. It is our crowded ark, one of an armada of vessels crammed thick with humanity. I have no desire to move from my cellar, where everything is cosy and peaceful by comparison.

A woman from one of the upstairs rooms cooks the meat, and there is plenty to share. All the cellar-men fill up the kitchen, joining in the feast of my good fortune. One man brings beer, another, bread; for this is our way of a night. We eat until Alfred’s bad humour is quite taken away, and we are friendly once again. When we have finished, we return to the cellar and Alfred finds our pallets as sure as a seagull finds its nest from the hundreds on a cliff. I stretch out, cradled in the comfort of my companions patting their stomachs, smacking their lips and wiping gravy off their chins.

Alfred lolls on his elbow, picking at his buckled teeth with a straw. His rough sandy hair stands up in surprised tufts. He shifts his thin hips, cracks out a fart and laughs at the sound. His mouth is soft, for all his endeavours to hide it beneath a broad moustache.

‘You know what, Abel?’ he muses. ‘When we strike it rich, we’ll be out of here. Get a nicer room.’

‘Why would we want that? There are so many friends here.’

He scowls. ‘So I’m just one of many, am I?’

‘Not at all, Alfred. You are my dearest friend.’

‘Ah, get away with you.’

He is pleased, and I do not know why he demurs. It is true: I would not find my way through each day without his guidance. The thought is alarming, so I push it away. He clears his throat.

‘Time to reckon up, Abel.’ He rubs his palms together in pleasure. ‘Our little ritual.’

And I remember: every night before we turn in, I count out our wages.

‘This is for lodging,’ I say. ‘This for breakfast. And midday food. This for drink. And this left over.’

‘More drink?’ says Alfred.

‘Hmm. No. I need better boots.’

‘That will not buy you boots.’

‘Then I shall save each day until I have enough.’ I hand the money to him. ‘Will you keep it safe for me? I lose things, you know. I will forget where I have put it.’

Alfred laughs. ‘You’d forget your head!’

‘Yes, you’re a wooden-head, and no mistake!’ calls a man further down the row of sacks.

‘Old dozy!’ another man takes up the cry.

‘It is true,’ I say, for so it is.

‘Come on, lads,’ mutters Alfred.

‘Oh, we like him, Alfred; even if he is tuppence missing.’

‘You know there’s no harm in it.’

One of them punches my upper arm. ‘You’re our lucky charm.’

‘Not one of us has got hurt since you joined us.’

‘So we’re not going to chase you off, eh?’

‘Not our Abel.’

‘You’re a bit of a miracle, as I hear it.’

‘Fished you out of the mud, they did.’

‘You were mostly mud yourself.’

‘You should of been a goner. By all accounts.’

‘No-one as goes in the river comes out. Save you.’

‘Got a bit of luck you’d like to rub off on me?’

‘Come on, Abel, how about a good rub-down!’

They roar with laughter and I decide it is best to join in. I ache for them to say more. To paint in the blank picture of my forgetting.

‘You were in the papers and everything. Come on, Alf, show us.’

Alfred unbuttons the neck of his shirt to a scatter of playful whistles and draws out a much-folded sheet of newspaper. He lays it across his knee, smoothing out the folds carefully.

‘There you are,’ says one, leaning over Alfred’s shoulder and jabbing at the page.

‘Watch it, Pete. You’ll tear a bloody hole in it.’

‘Look, Abel. That’s you, that is.’

I squint at the small engraving: a man’s head; nose prominent, eyes dark and deep-set, a shadow of hair on the chin. Below, a cluster of uniformed men around a prone figure. They look very pleased with themselves. Mysterious Gentleman Rescued, reads the headline. Startling Discovery, of Particular Interest.

‘You can read it?’

I realise I have been speaking out loud.

‘Didn’t know you were educated.’

‘Neither did I,’ I say.

They laugh, and are easy with me again.

‘You can see why they thought you were that Italian.’

‘Go on, say something wop. You know you can.’

I do not have to think: the words fly easily to my tongue. ‘Piacere di conoscerla.’

‘He’s a living marvel!’

‘Yes, but not that posh one, as went missing.’

‘They found him with his throat cut.’

‘And his trousers down!’

‘So you’re common as muck, like the rest of us.’

‘Better off with us lot, eh, Abel?’

‘I am,’ I agree, and it pleases them greatly.

‘Why did you jump?’ says one, more thoughtfully.

‘I do not remember,’ I say. ‘Maybe I fell in.’

‘Lot of drunks fall in. No offence.’

‘I am not offended.’

‘You don’t seem like a drunk.’

‘Well, you weren’t in the pudding club. That’s why the ladies tend to take a late swim.’

They chuckle again, and after a while Alfred shoos them away.

‘Don’t chase them off.’

‘Only trying to help out a pal.’ He sulks. ‘Give you a bit of peace.’

‘I know. But I like to hear them talk. Truly, I don’t remember.’

‘Remember what?’

‘Any of it. Falling in the river. Being pulled out. Anything before this cellar.’

‘Now you’re pulling my leg.’

‘Alfred, I am not.’

‘Abel, I know you’re a wooden-head at the best of times …’ He stops. ‘You mean it?’

‘I want to remember. I can’t. I look into myself and find nothing. Each morning I wake up …’

He looks worried. I decide to stop. The look changes to thoughtful, and then he smiles.

‘It’ll come back,’ he declares, with a certainty I do not share. ‘Big shock, that’s what it is. Thing like that’d scare any man out of his wits. Make him imagine all kinds of nonsense.’

‘You are sure?’

‘Course I am. Wouldn’t lie to you, would I?’

‘No. You are my friend.’

‘You keep me straight, Abel, you do.’ He smiles, and grasps my shoulder.

‘Right, listen up!’ bawls one of the cellar-men. All heads turn. ‘I am chief bully for the evening, and I have a treat for us all.’

He flourishes his hand towards a woman at his elbow. There are a few whistles and rumbles of approval.

‘Some of you know her, some of you don’t. Not a tooth in her head. Eh, May?’

The woman grins, demonstrating the truth of his statement.

‘So, steady up, lads, finish your idle chatter,’ he says. ‘A gobble for sixpence; a helping hand for three.’

They gather into a knot and lay out their coins. She seems unconcerned by the number of acts they are negotiating, eyes brightening only when the take is firmly stowed in her bodice. She leads the first into the corner. The rest turn their backs and share a pipe, acting as though they cannot hear his shallowing gasps.

‘You’ve got a bit left over, haven’t you, Abel?’ says Alfred casually.

‘I have,’ I say.

He waves towards the female, who is already taking her next customer in hand. I consider her fingers working at my body in a similar fashion.

‘It’s there for the taking.’

‘No,’ I decide.

He smiles. ‘Me neither.’

Although I do not wish to participate, I find it difficult to take my attention from the hunched bodies in the darkness. One of the men, satisfied now and lounging on his mattress, notices the direction of my gaze.

‘Come on, cold-fish,’ he shouts. ‘You can have one on me if you like.’ He tosses a few coins in the air. ‘It’ll make a man of you.’

He laughs, not unpleasantly, and those men who are not distracted by the woman turn to regard me.

‘You have got one, haven’t you?’

‘Maybe it’s a tiddler,’ chaffs one, waggling his little finger.

‘She doesn’t mind small fry, do you, May?’

The woman hoots, washing down her most recent bout with a mouthful of beer and scratching at her skirts.

‘Maybe it’s as lifeless as he is. That soaking in the river has made it as much good as a herring.’

‘The river’ll do that to a man. Turn his every part to mud.’

‘Don’t plague him so,’ says Alfred, and their eyes turn from me to him. He is examining the laces of his boots as though they are fascinating objects worthy of deep study.

‘Only our bit of fun, Alf.’

‘He doesn’t mind, do you, mate?’

‘No,’ I say truthfully.

One of them thumps me on the back.

‘See? We’re only jesting.’

‘You’re all right, Abel, even if you can’t get it up. Anytime you change your mind, though, first one’s on us. Right, lads?’

They murmur assent, raising their smokes and cups in a toast. Then, finished with their companionable teasing, they settle to the more stimulating activities of the evening. After some time, the woman completes her labours and departs.

It occurs to me that I have heard taunts like theirs before, and I scrabble in my head for when it might have been. Last night? Last year? The harder I search, the more elusive the answer. I close my eyes, and it comes to me: I stand encircled, hands bound. My mind stirs unpleasantly and I shake my head. Perhaps I do not want to remember, after all. But now I have called them up, they will not leave me.

Dead fish.

Dead man.

Corpse-kisser.

I have heard every name before and they do not sting. My mouth fills with bile. I blink, and am back in the cellar. Alfred is peering at me closely.

‘You all right, Abel? You look like you’ve seen a ghost.’

‘I am well,’ I lie.

‘They don’t mean anything by it,’ he says, and pats my knee.

‘I know.’

‘Don’t pay them any mind.’

‘I shall not.’

‘Some men are so,’ he reassures me.

‘Yes.’

He is sitting so close his thigh is pressed against mine.

‘Alfred,’ I say quietly.

‘Yes, Abel?’ he breathes.

‘Please let me speak to you.’

‘Is it about today?’ he grumbles.

‘Yes.’

‘I am tired, Abel. I do not wish to talk any longer.’

‘Please?’

‘Go to sleep, Abel.’

He turns, curving his back away from me. The cellar quietens into sleep.

I am left alone, now that there are no distractions. I roll up my sleeve, uncovering my left arm. It is the same shape and colour as it was this morning, the hair as dark, and sprouting a thick trail from elbow to wrist in the same fashion. It matches the right arm perfectly, except for the scar: now a pale silver trail.

I struggle to believe that it is a part of my body; yet when I cut into it, it was as familiar as looking into a dish of potatoes. I try to make sense of this, and tell myself it is because I spend my days and nights cutting open beasts, and am used to the sight of muscle, bone, yellow fat, grey slippery organs. I am not convinced. It is not the same. My flesh is quick; the beasts are dead.

How could my body accomplish such a feat of healing? I puzzle over this riddle but find no answer. Only a creeping fear: no true, honest man heals like this. Therefore, I am a monster.

My mind strains to escape from this terrible conclusion, for how can I live with such knowledge, with myself? I desire an answer, and for that answer to be that I am mistaken. My most sincere wish is to be man and not miracle. There is of course only one way to prove that I am a simple fellow who bleeds and heals in the slow, painful way of ordinary folk. I must cut myself again, and prove it wrong.

With a stolen candle stub in my pocket, I take myself to the yard privy. Alfred does not wake to ask me what I am about. I get out my pocket-knife. My fist closes about the handle, the blade hovers; I press the point into my forearm, where the last trace of the scar remains. I will cut myself in the same spot, and it will bleed, and I will have to bind it up. Yes. I will prove it was nothing more than a freakish mistake.

I draw the blade along my arm in a straight line, and my skin separates as it should. I close my eyes in relief, but when I open them once more I see the gash beginning to draw shut. It is most curious. I run the blade along the new join and tease it open. My body obeys, and parts its lips, only to begin closing once again the moment I lift the knife away.

A shallow cut proves nothing. I dig a little deeper. There is pain now, but one that rouses me to a strange wakefulness. As a man swimming underwater breaks the surface and feels breath fly back into his body, so do I fly into myself. My body sparks into liveliness, including that masculine part of me, which also raises its sleepy head. I grind my teeth: how can I possibly feel arousal with the cutting open of my arm? It is shameful. I would rather be the piece of dead meat that everyone calls me than this degraded creature.

I examine the wound, excitement mixing with horror. It gapes, and I can see through to the dark red within. I have seen enough meat cut open to know there should be blood, and now. Tentatively, I push the knife back in, draw it out once more. This time I should leak, but I do not. I turn my arm around in the small light, wondering at this mystery. The candle shows me what I do not wish to be real: other than a moist smearing on the metal itself, all is dry.

I stare at my disobedient arm, and once more the ragged edges of skin begin their drawing together. I push my finger into the hole to stop my body re-forming itself, but the flesh closes, pushing me out with a firm pressure, like the tongue of a cow. It takes a little while longer, but there is no halting the knitting-up of the slit.

I shake my head and tell myself that this is not a proper test. Perhaps only my left arm is possessed of these strange qualities. I should cut a different part of my body – but not my other arm, for that is too similar. I roll up the leg of my trousers to the knee, select a spot on the calf and push in the point of the blade.

A drop of blood trickles down, catching in the mat of hair. My heart leaps with joy; I am bleeding. But no more follows and already the cut is barely to be seen. I jab at a different spot and feel a fresh surge of hope when a fat red bead falls as far as my ankle. A second drop spills from the wound, followed by a third. Breath gathers tightly in my throat. I am a normal man: I bleed.

Then the flow thickens, and stops. The wound blinks its eye, and closes. This is not possible. I must be normal; I have to be. There must be some place on my body that does not heal. But where? I drag my trouser-leg up as far as it will go and poke the blade into the pale ochre skin of my thigh. There is barely a smear of scarlet for my trouble. I try again; healing occurs straight away.

Maybe I need to go faster, to beat my body at its game of healing. But however quickly I jab the point of the knife, each cut starts to close up before I have time to make the next; the quicker I stab myself the quicker the doors of my flesh slam shut, matching my frenzy for hurt with a frenzy for healing. My breath scales a ladder of panting gasps as I climb closer and closer to myself. I am – I am – I am not Abel. Rather, I am not merely Abel. I am broad as the desert, tall as the sky, deep as the ocean. I know the answer to all my questions. It is all so clear, so simple. I am—

So close. I soar towards the sun of understanding. As my body heals, heat sears my wings and I plummet into familiar darkness. There is no attainment to be found: my hand wearies, and I cease my battle. The knife is barely marked with moisture; the skin of my legs and arms flecked with creamy marks that fade as I watch. A few moments more and they are gone. My ribs heave up and down, and I realise I am weeping. The candle gutters and goes out.

I do not understand what manner of man can skewer himself with a knife and shed not one drop of blood, and have his body remake itself. I look like a man. I eat, drink, shit, sleep, lift and carry, the same as every one of my fellows. But I am unlike them. I do not know who I am, or what I am.