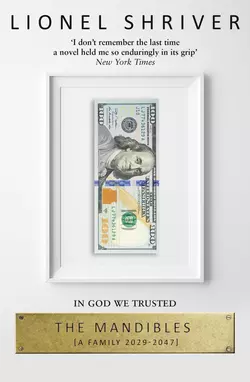

The Mandibles: A Family, 2029–2047

Lionel Shriver

‘Shriver’s intelligence, mordant humour and vicious leaps of imagination all combine to make this a novel that is as unsettling as it is entertaining’ FINANCIAL TIMESThe brilliant new novel from the Orange Prize-winning author of We Need to Talk about Kevin.It is 2029.The Mandibles have been counting on a sizable fortune filtering down when their 97-year-old patriarch dies. Yet America’s soaring national debt has grown so enormous that it can never be repaid. Under siege from an upstart international currency, the dollar is in meltdown. A bloodless world war will wipe out the savings of millions of American families.Their inheritance turned to ash, each family member must contend with disappointment, but also — as the effects of the downturn start to hit — the challenge of sheer survival.Recently affluent Avery is petulant that she can’t buy olive oil, while her sister Florence is forced to absorb strays into her increasingly cramped household. As their father Carter fumes at having to care for his demented stepmother now that a nursing home is too expensive, his sister Nollie, an expat author, returns from abroad at 73 to a country that’s unrecognizable.Perhaps only Florence’s oddball teenage son Willing, an economics autodidact, can save this formerly august American family from the streets.This is not science fiction. This is a frightening, fascinating, scabrously funny glimpse into the decline that may await the United States all too soon, from the pen of perhaps the most consistently perceptive and topical author of our times.

Copyright (#ulink_b42705bf-6ca0-502b-81ca-d276866f0b0e)

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Copyright © Lionel Shriver 2016

Cover design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Cover photographs © Nick Fielding/Alamy (banknote, front); Shutterstock.com (all other images) (http://shutterstock.com)

Lionel Shriver asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007560776

Ebook Edition © 2017 ISBN: 9780007560769

Version: 2017-02-15

Praise for The Mandibles: A Family, 2029–2047 (#ulink_bbfd17ee-a5c4-57fe-9fbe-96d5f1d019c4)

‘The Mandibles is so dazzlingly good that it might even mean Lionel Shriver won’t be described as “best-known for We Need To Talk About Kevin” for the rest of her career’

Reader’s Digest

‘As ever, Shriver cuts close to the bone! … Distinctly chilling’

Independent

‘A tale that fizzes with ideas and jokes … the comedy is pitch black’

The Times

‘All too chillingly plausible … a profoundly frightening portrait of how quickly the agreed rules of society can fall apart without money to grease the wheels’

Observer

‘Shriver is fast becoming the go-to novelist for some of the big issues of the day … breezy, mordantly comic … if the test of a futuristic novel is its eerie proximity to the present, this passes with flying colours’

Daily Mail

‘A powerful work investigating the fragility of the financial world. Prescient, imaginative and funny, it also asks deep questions’

Economist

‘Impressively sweeping … Shriver’s intelligence, mordant humour and vicious leaps of imagination all combine to make this a novel that is as unsettling as it is entertaining in its portrait of the cataclysmic unravelling of the American dream’

Financial Times

‘A sharp social eye and a blistering comic streak … her focus on nailing down the economic nitty-gritty of her plot is only one piece of the great, disconcerting fun she has in sending the world as we know it so vividly to hell’

New Yorker

‘Hilarious and brilliant … scary in the best possible way’

Elle

‘A provocative and very funny page-turner’

Wall Street Journal

‘Shriver really makes you think about the nature of money … By the end, The Mandibles had got under my skin’

Evening Standard

‘The stuff of nightmares … Shriver cleverly balances tragedy with black comedy’

Sunday Express

‘It’s scaring the hell out of me’

TRACY CHEVALIER

‘Shriver is as brilliant, funny and incisive as ever’

Woman and Home

‘A scary, depressing and convincing horror story, akin to reading about teetering on the edge of a precipice while actually teetering on the edge of a precipice’

Spectator

‘Insightful and darkly funny’

Good Housekeeping

‘Her verve and ambition are impressive … Few writers since William Gaddis in his brilliant JR have had the chutzpah to take on America’s particular money madness’

Mail on Sunday

‘A gripping family saga’

Daily Telegraph

‘By turns blackly funny and deeply unsettling’

Independent

‘Shriver writes with brio and intellectual zest. She is fiercely intelligent, but she has the qualities and virtues of the classical novelist. The ideas are fascinating, and the characters are thoroughly imagined and convincing … her gloomy vision is so brilliantly depicted that her novel is wonderfully enjoyable. If we are going to hell in a handcart, she makes the journey great fun’

Scotsman

‘Imaginative’

Sunday Times

‘Dystopian fable punctuated by comedy so dark it practically disappears into the shadows … brilliantly unforgiving’

The Times

‘A gleeful nightmare, it made me snort with laughter even as I was shuddering’

SARAH WATERS, Guardian

‘Brilliant satire … frankly terrifying’

SARAH CHURCHWELL, Guardian

‘Searing … establishes her firmly as the Cassandra of American letters … I don’t remember the last time a novel held me so enduringly in its grip’

New York Times

‘The energy of Shriver’s style counteracts the remorselessness of her vision’

JANE SMILEY, Guardian

Dedication (#ulink_32304f10-eb1c-58f2-8e8a-5fa815bd0ac8)

TO BRADFORD HALL WILLIAMS.

Although you had little time for fiction,

you’d have liked this book.

Who would have imagined that a cantankerous

misanthrope would be so fiercely missed?

Epigraph (#ulink_41442915-3e66-5066-aae3-12d32742a328)

Collapse is a sudden, involuntary and chaotic form of simplification.

—James Rickards, Currency Wars

Contents

Cover (#u3cb93340-c8fe-52d3-abdd-22d191cdced1)

Title Page (#uaf3477e7-6bdc-5de3-968c-8c5b45fb5f63)

Copyright (#uef9c94a9-d01d-5168-9081-d287ff73d40c)

Praise for The Mandibles: A Family, 2029–2047 (#u3d42ce8a-e638-5b42-b27c-281f7f77ede0)

Dedication (#u28d4b230-0609-5713-8ccb-8959c700af8e)

Epigraph (#u2de10088-2491-5b61-8f25-6940b6ea7b14)

2029 (#u56804b5d-2de0-56f5-909f-3a057f16933e)

Chapter One: Gray Water (#u67951002-1c89-55c8-ada3-9b69c9054257)

Chapter Two: Karmic Clumping (#ud42bd519-0c84-5852-a881-9c4b604e2821)

Chapter Three: Waiting for the Dough (#udad593b2-b189-55fc-9782-fb8e3909e368)

Chapter Four: Good Evening, Fellow Americans (#u31501e9b-ad6b-5ba7-a00e-12c777598dc5)

Chapter Five: The Chattering Classes (#ud6595abc-8cae-5dfe-a3f5-3830084e4f14)

Chapter Six: Search and Seizure (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven: The Warrior Queen Arrives in Carroll Gardens (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight: The Joys of Being Indispensable (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine: Foul Matters (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten: Setbacks Never Bring Out the Best in People (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven: Badder Bitter Gutter (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve: Agency, Reward, and Sacrifice (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen: Karmic Clumping II (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen: A Complex System Enters Disequilibrium (#litres_trial_promo)

2047 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One: Getting with the Program (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Two: So Tonight We’re Gonna Party Like It’s 2047 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Three: Return of the Somethingness: Shooting Somebody, Going Somewhere Else, or Both (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Four: Singin’ This’ll Be the Day That I Die (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Five: Who Wants to Live in a Utopia Anyway (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Lionel Shriver (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

2029 (#ulink_e2ea4220-e975-5a0d-90ec-c4bf2b0f9a6c)

chapter one (#ulink_af12cc53-237f-5322-9f7b-4b1e379f34d6)

Gray Water (#ulink_af12cc53-237f-5322-9f7b-4b1e379f34d6)

Don’t use clean water to wash your hands!”

Intended as a gentle reminder, the admonishment came out shrill. Florence didn’t want to seem like what her son would call a boomerpoop, but still—the rules of the household were simple. Esteban consistently flouted them. There were ways of establishing that you weren’t under any (somewhat) older woman’s thumb without wasting water. He was such a cripplingly handsome man that she’d let him get away with almost anything else.

“Forgive me, Father, for I have sinned,” Esteban muttered, dipping his hands into the plastic tub in the sink that caught runoff. Shreds of cabbage floated around the rim.

“That doesn’t make sense, does it?” Florence said. “When you’ve already used the clean, to use the gray?”

“Only doing what I’m told,” her partner said.

“That’s a first.”

“What’s put you in such a good mood?” Esteban wiped his now-greasy hands on an even greasier dishtowel (another rule: a roll of paper towels lasts six weeks). “Something go wrong at Adelphi?”

“Things go nothing but wrong at Adelphi,” she grumbled. “Drugs, fights, theft. Screaming babies with eczema. That’s what homeless shelters are like. Honestly, I’m bewildered by why it’s so hard to get the residents to flush the toilet. Which is the height of luxury, in this house.”

“I wish you’d find something else.”

“I do, too. But don’t tell anybody. It would ruin my sainted reputation.” Florence returned to slicing cabbage—an economical option even at twenty bucks. She wasn’t sure how much more of the vegetable her son could stand.

Others were always agog at the virtuousness of her having taken on such a demanding, thankless job for four long years. But assumptions about her angelic nature were off base. After she’d scraped from one poorly paid, often part-time position to another, whatever wide-eyed altruism had motivated her moronic double major in American Studies and Environmental Policy at Barnard had been beaten out of her almost entirely. Half her jobs had been eliminated because an innovation became abruptly obsolete; she’d worked for a company that sold electric long underwear to save on heating bills, and then suddenly consumers only wanted heated underwear backed by electrified graphene. Other positions were eliminated by what in her twenties were called bots, but which displaced American workers now called robs, for obvious reasons. Her most promising position was at a start-up that made tasty protein bars out of cricket powder. Yet once Hershey’s mass-produced a similar but notoriously oily product, the market for insect-based snacks tanked. So when she came across a post in a city shelter in Fort Greene, she’d applied from a combination of desperation and canniness: the one thing New York City was bound never to run out of was homeless people.

“Mom?” Willing asked quietly in the doorway. “Isn’t it my turn for a shower?”

Her thirteen-year-old had last bathed only five days ago, and knew full well they were all allotted one shower per week (they went through cases of comb-in dry shampoo). Willing complained, too, that standing under their ultra-conservation showerhead was like “going for a walk in the fog.” True, the fine spray made it tricky to get conditioner out, but then the answer wasn’t to use more water. It was to stop using conditioner.

“Maybe not quite yet … but go ahead,” she relented. “Don’t forget to turn off the water while you’re soaping up.”

“I get cold.” His delivery was flat. It wasn’t a complaint. It was a fact.

“I’ve read that shivering is good for your metabolism,” Florence said.

“Then my metabolism must be awesome,” Willing said dryly, turning heel. The mockery of her dated vernacular wasn’t fair. She’d learned ages ago to say malicious.

“If you’re right, and this water thing will only get worse?” Esteban said, taking down plates for dinner. “Might as well open the taps full-on while we can.”

“I do sometimes fantasize about long, hot showers,” Florence confessed.

“Oh, yeah?” He encircled her waist from behind as she cored another cabbage wedge. “Deep inside this tight, bossy choirgirl is a hedonist trying to get out.”

“God, I used to bask under a torrent, with the water hot as I could bear. When I was a teenager, the condensation got so bad once that I ruined the bathroom’s paint job.”

“That’s the sexiest thing you’ve ever told me,” he whispered in her ear.

“Well, that’s depressing.”

He laughed. His work entailed lifting often-stout elderly bodies in and out of mobility scooters—mobes, if you were remotely hip—and it kept him in shape. She could feel his pecs and abdominal muscles tense against her back. Tired, certainly, and she might be all of forty-four, but that made her a spring chicken these days, and the sensation was stirring. They had good sex. Either it was a Mexican thing or he was simply a man apart, but unlike all the other guys she’d known, Esteban hadn’t been raised on a steady diet of porn since he was five. He had a taste for real women.

Not that Florence thought of herself as a great catch. Her younger sister had bagged the looks. Avery was dark and delicately curved, with that trace of fragility men found so fetching. Sinewy and strong simply from keeping busy, narrow-hipped and twitchy, with a long face and a mane of scraggly auburn hair eternally escaping the bandana she wore pirate-style to keep the unruly tendrils out of the way, Florence had often been characterized as “horsey.” She’d interpreted the adjective as pejorative, until Esteban latched on to the descriptor with affection, slapping the haunches of his high-strung filly. Maybe you could do worse than to look like a horse.

“See, I got a whole different philosophy,” Esteban mumbled into her neck. “Ain’t gonna be no more fish? Stuff your face with Chilean sea bass like there’s no tomorrow.”

“The danger of there being no tomorrow is the point.” The school-marmish tut-tut was tempered with self-parody; she knew her stern, upright facade got on his nerves. “And if everyone’s reaction to water scarcity is to take half-hour showers ‘while they can,’ we’ll run out of water even sooner. But if that’s not good enough for you? Water is expensive. Immense expensive, as the kids say.”

He let go of her waist. “Mi querida, you’re such a drear. If the Stonage taught us anything, it’s that the world can go to hell in a snap. In the little gaps between disasters, might as well try to have fun.”

He had a point. She’d intended to eke out this pound of ground pork through two meals; it was their first red meat for a month. After Esteban’s urging to seize the day, she decided rashly on one-time portions of five ounces apiece, dizzy with profligacy and abandon until she caught herself: we are supposed to be middle class.

At Barnard, having written her honors thesis on “Class, 1945–Present” had seemed daring, because Americans flattered themselves as beyond class. But that was before the fabled economic downturn that fatally coincided with her college graduation. After which, Americans talked about nothing but class.

Florence embraced a brusque, practical persona, and self-pity didn’t become her. Thanks to her grandfather’s college fund, her debts from a pointless education were less onerous than many of her friends’. She may have envied her sister’s looks, but not Avery’s vocation; privately, she considered that fringy therapeutic practice, “PhysHead,” parasitical humbug. Florence’s purchase of a house in East Flatbush had been savvy, for the once-scruffy neighborhood had gone upscale. Indians were rioting in Mumbai because they couldn’t afford vegetables; at least she could still spring for onions. Technically Florence may have been a “single mother,” but single mothers in this country outnumbered married ones, and the very expression had fallen out of use.

Yet her parents never seemed to get it. Although they fell all over themselves proclaiming how “proud” they were, the implication that into her forties their eldest required you-go-girl cheerleading was an insult. Now their fawning over this shelter position was unendurable. She hadn’t taken the job because it was laudable; she’d taken it because it was a job. The shelter provided a vital public service, but in a perfect world that service would have been provided by someone else.

True, her parents had suffered their own travails. Her father Carter had long felt like an underachiever in print journalism, being stuck for ages at Long Island’s Newsday, and never snagging the influential, better remunerated positions for which he felt he’d paid his dues. (Besides, Dad always seemed to have an edge on him in relation to his sister Nollie, who hadn’t, in his view, paid any dues, and whose books, he’d insinuated more than once, were overrated.) Yet toward the end of his career he did get a job at his beloved New York Times (God rest its soul). The post was only in the Automobiles section, and later in Real Estate, but having made it into the paper he most revered was a lifelong tribute. Her mother Jayne lurched from one apocalyptic project to the next, but she ran that much-adored bookstore Shelf Life before it went bust; she ran that artisanal deli on Smith Street before it was looted during the Stone Age and she was too traumatized to set foot in it again. And they owned their house, didn’t they—free and clear! They’d always owned a car. They’d had the usual trouble juggling family and career, but they did have careers, not plain old jobs. When Jayne got pregnant late in the day with Jarred, they worried about the age gap between a new baby and their two girls, but neither of them anguished, as Florence had when pregnant with Willing, over whether they could afford to keep the kid at all.

So how could they grasp the plight of their elder daughter? For six long years after graduation Florence had to live with her parents in Carroll Gardens, and that big blot of nothingness still blighted her résumé. At least her little brother Jarred was in high school and could keep her company, but it was humiliating, having toiled on that dopey BA only to trial novel recipes for peanut-butter brownies with mint-flavored chocolate chips. During the so-called “recovery” she moved out at last, sharing cramped, grungy digs with contemporaries who also had Ivy League degrees, in history, or political science, and who also brewed coffee, bussed tables, and sold those old smart phones that shattered and you had to charge all the time at Apple stores. Not one lame-ass position she’d copped since bore the faintest relation to her formal qualifications.

True, the US bounced back from the Stone Age more quickly than predicted. New York restaurants were jammed again, and the stock market was booming. But she hadn’t followed whether the Dow had reached 30,000 or 40,000, because none of this frenzied uptick brought Willing, Esteban, and Florence along with. So maybe she wasn’t middle class. Maybe the label was merely the residue of hailing from a learned, literary family, what you clung to in order to separate yourself from people who weren’t much worse off than you. There weren’t many dishes you could prepare from only onions.

Mom!” Willing cried from the living room. “What’s a reserve currency?”

Wiping her hands on the dishtowel—the cold gray water hadn’t cut the grease from the pork patties—Florence found her son freshly washed with his dark, wet hair tousled. Though having grown a couple of inches this year, the boy was slight and still a bit short considering he’d be fourteen in three months. He’d been so rambunctious when he was small. Yet ever since that fateful March five years ago, he’d been, not fearful exactly—he wasn’t babyish—but watchful. He was too serious for his age, and too quiet. She sometimes felt uncomfortably observed, as if living under the unblinking eye of a security camera. Florence wasn’t sure what she’d want to hide from her own son. Yet what best protected privacy wasn’t concealment but apathy—the fact that other people simply weren’t interested.

Also somber for a cocker spaniel—though the forehead’s perpetual rumple of apprehension may have indicated a drop of bloodhound—Milo was flopped beside his master, chin glumly on the floor. His chocolate coat was glossy enough, but the brown eyes looked worried. What a team.

Typically for this time of evening, Willing wasn’t propped before video-game aliens and warlords, but the TV news. Funny, for years they’d predicted the demise of the television. Channels were streamed, but the format had survived—providing the open fire, the communal hearth, that a personal device could never quite replace. With newspapers almost universally defunct, print journalism had given way to a rabble of amateurs hawking unverified stories and always to an ideological purpose. Television news was about the only source of information she faintly trusted. The dollar now having dropped below 40 percent of the world’s … a newscaster was yammering.

“I’ve no idea what a reserve currency is,” she admitted. “I don’t follow all that economics drear. When I graduated from college, it was all people talked about: derivatives, interest rates, something called LIBOR. I got sick of it, and I wasn’t interested to begin with.”

“Isn’t it important?”

“My being interested isn’t important. I swear, I read newspapers front to back for years. My knowing any of that stuff, most of which I’ve forgotten, hasn’t made the slightest difference. I wish I had the time back, frankly. I thought I’d miss newspapers, and I don’t.”

“Don’t tell Carter that,” Willing said. “You’d hurt his feelings.”

Florence still winced at that “Carter.” Her parents had urged all their grandchildren to address them by first names. “Only” fifty and fifty-two when Avery had her first child, they’d resisted “Grandma and Granddad” as connoting a geriatric status with which they couldn’t identify. They obviously imagined that being “Jayne and Carter” to the next generation would induce a cozy, egalitarian palliness, as if they weren’t elders but buddies. Supposedly, too, the rejection of convention made them bold and cutting-edge. But to Florence, it was awkward: her son referenced her parents with more familiarity than she did. Their refusal to accept the nomenclatural signature of what they actually were—Willing’s grandparents, like it or not—suggested self-deceit, and so was purely a gesture of weakness, one that embarrassed her for them if they didn’t have the wit to be embarrassed on their own accounts. The forced chumminess encouraged not intimacy but disrespect. Rather than remotely nonconformist, the “Jayne and Carter” routine was tiresomely typical for baby boomers. Nevertheless, she shouldn’t take her exasperation out on Willing, who was only doing what he was told.

“Don’t worry, I’d never bad-mouth newspapers to your grandfather,” Florence said. “But even during the Stone Age—everyone thought it was so awful, and some aspects of it were awful. But, gosh, for me liberation from all that noise was dead cool”—she raised her hands—“sorry! It was careless. Everything seemed light and serene and open. I’d never realized that a day was so long.”

“You read books again.” Mention of the Stone Age made Willing pensive.

“Well, the books didn’t last! But you’re right, I did go back to books. The old kind, with pages. Aunt Avery said it was ‘quaint.’” She patted his shoulder and left him to the Most Boring Newscast Ever. Christ, she must have the only thirteen-year-old in Brooklyn riveted by the business report.

Checking the rice, she tried to remember what her weirdo son had claimed about the recrudescence of malnutrition in Africa and on the subcontinent, after both regions had made such strides. It was an outrage that the poor simply couldn’t afford to eat, she’d bemoaned to the boy, when the planet had plenty of food. He’d responded obtusely, “No, it doesn’t.” He proceeded to recapitulate his great-grandfather’s tortured explanation—something like, “It only seems like there’s plenty of food. If you gave the poor more money, then the price would rise even higher, and then they still couldn’t afford it.” Which didn’t make the slightest sense. Around Willing, she should monitor her grandfather’s propaganda more closely. The old man was liberal by creed, but she’d never met anyone with money who didn’t have conservative instincts. One such instinct was to make the morally obvious (if fiscally inconvenient) seem terribly complicated. Like, rice is too costly, then give people the money to buy it. Duh.

Willing seemed so subdued and unassuming at school, but behind closed doors that kid could get a bit full of himself.

“By the way, I’ve arranged to talk to my sister after dinner,” she told Esteban as he reached for a cold beer. “So I hope you don’t mind doing the dishes.”

“Let me use real water, I’ll do the dishes every night.”

“The gray is real enough, just not especially clear.” She didn’t want to have this battle every evening, and was relieved that he changed the subject as the pork sizzled.

“Met this afternoon with the new group we’re taking up Mount Washington,” Esteban said. “Already identified the trouble-maker. It’s never the weak, pathetic clients who give us grief, but these geriatric superheroes. Usually guys, though sometimes it’s some tough, I-still-think-I’m-thirty-five old bag held together with Scotch tape and several hundred grand in plastic surgery.”

He knew she didn’t like him to talk about his charges with such contempt, but presumably he had to get the frustration out of his system beyond their earshot. “So who’s the headache? Jesus, this meat’s so full of water, these patties will be boiled.”

“Must be the other side of eighty. Has that look, with these stringy biceps—spends hours in the gym and hasn’t noticed that he’s now doing curls with barbells made of balsa wood. Wouldn’t listen to my safety drill. His only question was how we dealt with the fact that people ‘keep to different paces,’ and some climbers prefer to ‘push themselves.’ He’s a type. They’re runners, or used to be, though that was before their double hip replacements and five keyhole heart surgeries. You can bet they have money, and back before the dawn of time they did something with stroke. So nobody’s dared to tell them they’re fucking old. Usually their doctor or their spouse has laid down the law that they can’t troop into the woods anymore without someone to scoop them up when they stumble down a gully and break their legs. But they never like the whole idea of trekking with a group, and they always look around at the other arthritic losers and think, What am I doing with these boomerpoops?—when actually they fit right in. They don’t follow directions and they don’t wait up. They’re the ones who have accidents and give Over the Hill a bad rep. On a canoe trip, they’re the ones who splash off solo and take the wrong tributary, and then we have to abandon the whole expedition to find them. Because they don’t like following a guide. Especially a Lat guide. They’re enraged that Lats are running the show now, since somebody has to—”

“Enough.” Florence threw the cabbage into what was starting to look like pork soup. “You forget. I’m on your side.”

“I know you get sick of it, but you’ve no idea the waves of resentment I get from these crusties every day. They want their domination back, even if they think of themselves as progressives. They still want credit for being tolerant, without taking the rap for the fact that you only ‘tolerate’ what you can’t stand. Besides, we gotta tolerate honks same as they gotta put up with us. It’s our country every bit as much as these has-been gringos’. It’d be even more our country if these tottering white cretins would hurry up and die already.”

“Mi amado, that’s too far,” she chided pro forma. “Please don’t talk that way around Willing.”

As ever, Florence didn’t have to ask her partner to set the table, fill the water glasses, and replenish the saltshaker. Esteban had been raised in a crowded household, and pitched in as a matter of course. He was the first boyfriend to convince her that just because she didn’t need companionship, and she didn’t need help raising her son, didn’t mean she couldn’t still like a man in her bed, and like for Willing to enjoy some semblance of a father—one who could take credit for the boy having become fluently bilingual. At once, Esteban was second generation, and spoke English with no trace of an accent; occasional insertions of Spanish were mostly tongue in cheek, a droll playing to stereotype that his elderly clients lapped up. He may not have gone to college, but that was a smart financial move, in her view.

As for the ethnic issue, it was not true, as her sister clearly believed, that she had latched on to a Lat to be hip (whoops! careless), to join what she could not beat, or to disavow her heritage out of a hackneyed liberal shame. Esteban was a forceful, responsible, vital man regardless of his bloodlines, and they had plenty in common, not least that their favorite emotion was disgust. All the same, the choice of a Mexican lover felt on the right side of history—open and melding and forward-looking—and she had to admit his background was a plus. Whether she’d still be so drawn to the man if he were a regular white guy was a question that didn’t bear asking. People were package deals. You couldn’t separate out who they were and what they were, and the bottom line was that she found Esteban’s nut-colored complexion, silken black tail braid, and wide, high cheekbones irresistibly sexy. In his otherness, he enlarged her world, and granted her access to a rich, complex American parallel universe that for battened-down rightwing paranoids like her sister Avery solely constituted an impenetrable, monolithic threat.

“Hey, remember the guy who moved in across the street last year?” Florence mentioned when Esteban returned to sweep up the bits of cabbage from the kitchen floor. “Brendan Somebody. I told you at the time it was a sign I’d never be able to buy a house in this neighborhood now. He works on Wall Street.”

“Yeah, dimly. Investment banker, you said.”

“I ran into him on the way to the bus stop this morning, and we had a pretty strange conversation. I think he was trying to be helpful. I get the feeling he likes me.”

“Whoa, don’t like the sound of that!”

“Oh, I’m sure it’s more of that disgusting reputation for goodness and mercy that follows me around like a wet stray. So he told me that we should move ‘our investments’ out of the country—right away, today. We should transfer any cash into a foreign currency—like, what cash? I wish it weren’t so funny—and get out of any, quote, ‘dollar-denominated assets.’ God, he was theatrical about it. Maybe that sort doesn’t get much drama coming their way. He touched my shoulder, and looked me straight in the eye, like this is totally fucking serious and I’m not joking. It was hysterical. I have no idea what makes him think people like us have ‘investments.’”

“We might if only your rich abuelo would keel over.”

“Our seeing a dime of that inheritance would also entail my parents keeling over, so don’t tempt fate.”

Although Esteban was no gold digger, any reference to the Mandible fortune—of what size no one seemed to know—made Florence uncomfortable. A wealthy paternal grandfather hadn’t appreciably affected her modest upbringing. Over time, she had devoted a great deal of effort to persuading a Lat boyfriend that she was not yet another lazy, cosseted, entitled gringo who didn’t deserve her good luck, and whenever the money came up, that spoiled caricature reared its head again. It was touchy enough that she held the deed to 335 East Fifty-Fifth Street, and had resisted Esteban’s offers to contribute to the mortgage payments. They’d been together for five years, but allowing him to build a claim to the equity would have meant trusting the relationship an increment further than felt fitting, given that a string of his predecessors had proved such spectacular disappointments.

“What do you think is going on that made the guy say that,” Esteban asked, “out of the blue?”

“I don’t know. I overheard on the news that some bank in Britain went bust a couple of days ago, but big deal. That has nothing to do with us. And yesterday, what, a something-something didn’t ‘roll over’ something …? You know I don’t follow this stuff. And that was somewhere in Europe, too. After years of that ‘orderly unwinding of the euro,’ I’m immense burned out on their everlasting financial problems. Anyway, the news Willing was watching definitely said something about bonds. But I bet Brendan was just trying to impress me.

“Oh, and talk about super weird,” she recalled, plating up, “Brendan asked if we were homeowners. When I said yes, though a tenant helped cover the mortgage, he said, ‘Ownership might prove auspicious. The tenant you may regret.’”

With those where-were-you-then junctures—for people like his great-aunt Nollie, the Kennedy assassination; for his mother’s generation, 9/11—it was all too easy to pretend-remember, to look back and impose the solid facts of what you learned afterward on the tremulous, watery past. So Willing resolved that later he would remember this night, truly remember-remember—right down to the sandy-textured pork patties, a long video powwow between his mother and her sister after dinner, and the dryout (by then, the protocol was routine). He would keep humbly in place the fact that he did not, at this time, understand the notion of a reserve currency. Nor did he comprehend what a bond auction was, although there’d doubtless been whole decades if not centuries during which both concepts were roundly regarded as boring and beside the point by just about everybody. Still, in the future he would make sure to give himself this much credit: during the 7 p.m. newscast, even if he didn’t get it—this “US Treasury bond auction” with its “spike in interest rates”—he did pick up on the tone.

Since the Stonage, he’d had an ear for it. Everyone else thought that the worst was behind them; order had been gloriously and permanently restored. But for Willing, during his own seminal where-were-you-then occasion at the grand old age of eight, The Day Nothing Went On had been a revelation, and revelations did not un-reveal themselves; they did not fit back into the cupboard. As a consequence of this irreversible epiphany, he had learned to upend expectations. There was nothing astonishing about things not working, about things falling apart. Failure and decay were the world’s natural state. What was astonishing was anything that worked as intended, for any duration whatsoever. Thus he’d spent his latter childhood in a state of grateful amazement—at the television aglow with supersaturated color (it turned on! again!), at his mother returned from work on a bus that ran on time or at all, at clean water flowing from the tap, even if he was rarely allowed to touch it.

As for the tone, he identified it while his mother was still chattering over cabbage in the kitchen. Neither his mother nor Esteban detected the timbre. Only Willing paid attention. Willing and Milo, that is; eyes alert, posture wary, ears lifted, the spaniel discerned a curious pitch as well. For the newscasters spoke with a strain of nervous excitement that was distinctive. People who delivered the news loved it when something happened. You could hardly blame them, since saying what happened was their job, and they liked having something to do. When events were bad, as they almost always were since good news was mostly about sameness, they’d get embarrassed by how happy they were. The worst of the anchors covered the happiness with big overdone fake sadness that didn’t fool anyone and that Willing wished they would ditch.

At least tonight nobody had died, and whatever inscrutable occurrences were being reported had to do with numbers and clunky expressions that he bet most of the rest of the audience didn’t understand either. So at least the newsreaders and their guests didn’t pull their cheeks down and drop their voices into an artificially sorrowful minor key. To the contrary, everyone on the newscast seemed pleased, thrilled even. Yet the edgy gaiety was etched with a keen awareness that to the best of their abilities they should mask an exhilaration they would come to regret. The tone came down to: this is fun now, and it won’t be later.

chapter two (#ulink_15efed93-bf1b-53f6-9e4f-5b9dfb9c0bcc)

Karmic Clumping (#ulink_15efed93-bf1b-53f6-9e4f-5b9dfb9c0bcc)

Avery Stackhouse was well aware that her sister was impatient with fleXface, since Florence liked to clean the kitchen while she talked. But in that event, the dishes always seemed to command the better part of her attention, and the distraction would squander a rare solitude: Lowell was teaching an evening class; Savannah was out with one of the boyfriends shuttling through her senior year so quickly that her mother had given up learning their names; Goog was prepping with his team for the big interschool debate on the proposition “Shortages and price spikes are caused by destructive national ‘food security’ policies, not by real agricultural shortfalls”—Goog had opted for the affirmative; Bing was practicing with his quartet.

Curling into a sumptuous armchair, she gave the living room a satisfied glance. In her young adulthood, fashionable décor had featured hard surfaces, sharp angles, and refraction, while color schemes were dominated by unforgiving whites. Deliciously, now softness, light absorption, and curves were de rigueur; even their walls were covered in dusty synthetic suede. This room was all umbers and toast, the furniture pre-worn leather and low-nap fur, so that lazing here with a glass of wine was like snuggling against a stuffed bear. The tacky blare of chrome had been replaced with the mute of pewter. Mercifully, affluent homes in DC no longer sported those dreadful sectionals, but had restored the dignified couch.

The Stackhouses had also banished the busy clunk of books that cluttered all three stories of her parents’ jumbled brick house in Carroll Gardens. Nothing betrayed you as a fuddy-duddy like parallels of shabby spines junking up the walls. Once you’d read a book, why retain it in three dimensions, save as a form of boasting? Now that you could balance the Library of Congress on your fingertip, dragging countless cartons of these spent objects from home to home was like moving with your eggshells.

She unfolded and stiffened the fleXcreen to perch it on the hide-covered coffee table. The device was so thin that, before the distinctive bright colors of its second generation, some folks had thrown theirs away, mistaking the wads in their pockets for tissues. Since the diaphanous material would assume a screen size anywhere from a two-inch square to a fifteen-by-twenty rectangle, and you could fold a lower section onto a surface to become a keyboard, the fleX had replaced the smart watch, smartspeX, smart phone, tablet, laptop, and desktop at a stroke. Best of all, the fleXcreen didn’t break—a plus its manufacturers were beginning to rue.

“Listen, are you settled?” Avery plunged in. “Because I’m dying to talk to you about this farm Jarred’s bought.”

“Yeah, Dad said something about it,” said Florence. “But how can Jarred swing buying a farm?”

High resolution brought out incipient bags under her sister’s eyes that wouldn’t have been noticeable in person. Avery wasn’t inclined to feel superior; flaws in her sister’s visage were harbingers of her own in two years’ time. Besides, a host of blotches, sprouting black hairs, and ghastly discolorations glared on her face as well. The device’s forensic images so exceeded the benevolently blurred apprehension of the human face in ordinary life that video resembled a medical scan, which wouldn’t tell you whether your sister was happy or sad but whether she had skin cancer. At least she and Florence had agreed to never go 3-D again, which was even worse: you looked not only malignant, but fat.

“Because Jarred never tapped the college fund for nearly as much as you and I did,” Avery explained, “he convinced Grand Man that getting a down payment instead would be fair.” A formidable man of formidable vanities, Grandfather Mandible had always seemed to savor the shorthand Grand Man—even more so once her children embellished it to Great Grand Man.

“Leave it to Jarred to cash in on dropping out of college,” Florence said. “Twice. Still, I’m baffled. Jarred’s never even expressed interest in gardening.”

“He’d never expressed interest in seawater before he went on that desalination jag. He’d never fried an egg before he took that Moroccan cooking course. Jarred’s whole life is a ‘What doesn’t belong in this picture?’ puzzle where nothing belongs in the picture. An agrarian idyll doesn’t fit, so it does fit. It’s logical in its illogic.”

“Is this how you bend over backwards getting your clients to make sense of their lives? I’m impressed. That was athletic.”

“The truth is, Mom and Dad have been immense encouraging. They think the farm is great. Anything to get him to move out.”

“Gosh, leaving home at the tender age of thirty-five—isn’t that brave!” They shared a collusive laugh. They were the adults, and whatever their failings at least neither sister was the family’s shiftless, self-indulgent fuck-up. “So where is this place?”

“Gloversville, New York, if you can believe it,” Avery said. “Where they used to make gloves or whatever.”

“Don’t mock. Every town in this country used to make something. What does this place grow?”

“It’s got some apple and cherry trees. Carrots, corn. I think he even inherited a few cows. One of those family farms, where the owners got too old and the kids wanted nothing to do with it.”

“Those concerns always run at a loss,” Florence said. “And he’s in for a shock. Small-scale farming is backbreaking work. Nuts—I haven’t talked to him in months.”

“He’s taken a survivalist turn. He’s calling the property Citadel, as if it’s a fortress. The last few times we’ve talked he’s been pretty dark. All this End of Days stuff. It’s so weird: I walk around the District, the bars are packed, property prices are skyrocketing again, and everyone’s easing in the back of those driverless electric cars that cost two hundred grand. The Dow has the investment equivalent of high blood pressure. And meantime our little brother is holed up with these doomsaying downloads: Repent, the end is nigh! The center cannot hold, we’re all about to die! The text he devours is secular, but the emotional appeal is evangelical Iowa. No wonder he’s ended up on a farm.”

“Well, a lot of people had that reaction to the Stone Age—”

“You crack me up. Nobody says that anymore.”

“Call me a pedant, but blurred into ‘the Stonage’ it loses any of its as-in-bombed-back-into meaning—”

“You are a pedant. Just like Dad. Language is alive, and you can’t put it in the freezer. But never mind. I don’t think Jarred is having a delayed reaction to the-Stone-Age.” Avery spaced the expression elaborately, as she might condescend to a moron who had to have it spelled out that “AC” was air con-di-tion-ing. “This idea of his—and it’s hardly unique to Jarred, right? The conviction that we’re teetering on a precipice, about to pitch into freefall? It’s all projection. It has nothing to do with ‘the world’ or the terrible course this country has taken for which we’re all going to pay. It has everything to do with Jarred’s sense of personal precariousness. It’s a pessimism about his future. But worrying about the collapse of civilization instead of the collapse of his hopes to become a desalination expert because the qualifications were too much trouble, well—the global prophecy makes him feel more important.”

“Ever share this theory with Jarred?” Florence said. “He might not care to have his political opinions dismissed as being only about his relationship to himself. The stuff he gets fired up about—species extinctions, desertification, deforestation, ocean acidification, the fact that not one major economy has kept to its carbon-reduction commitments—it’s not only in his mirror.”

“But I see the same thing in my elderly clients all the time. They have different obsessions, of course: we’re about to run out of water, or run out of food, or run out of energy. The economy’s on the brink of disaster and their 401(k)s will turn into pumpkins. But in truth they’re afraid of dying. And because when you die, the world dies, too, at least for you, they assume the world will die for everybody. It’s a failure of imagination, in a way—an inability to conceive of the universe without you in it. That’s why old people get apocalyptic: they’re facing apocalypse, and that part, the private apocalypse, is real. So the closer their personal oblivion gets, the more certain geriatrics project impending doom on their surroundings. Also, there’s almost a spitefulness, sometimes. I swear, for some of these bilious Chicken Littles, imminent Armageddon isn’t a fear but a fantasy. Like they want the entire planet to implode into a giant black hole. Because if they can’t have their martinis on the porch anymore then nobody else should get to sip one, either. They want to take everything with them—down to the olives and the toothpicks. But actually, everything’s fine. Life, and civilization, and the United States, are all going to go on and on, and that’s really what they can’t stand.”

Florence chuckled. “That was a set piece. You’ve said it before.”

“Mm,” Avery allowed. “Maybe once or twice. But my point about Jarred stands. He’s busy deepening his well and stockpiling cans of beef stew because he’s experiencing a crisis of psychic survival. Once he gets through it, he’ll look around at his multiple first-aid kits and whole cases of extra-long safety matches and feel pretty silly.”

“Uh-huh. But Jarred may not be the only one projecting. Your life’s going swell, so everywhere you look is sunny.”

That swell was dismissive, and Avery didn’t appreciate having the tools of her own analysis turned against her. “Making a halfway decent living doesn’t turn you into a dimwit,” she objected. “And the comfortably off have problems, too.”

“Uh-huh,” Florence said again. “Name one.” She didn’t even wait for an answer. “As for Jarred, the trouble with his latest boondoggle is practical, not psychic. This ‘Citadel’ debacle sounds like a financial sinkhole. He’s already in hock up to his eyeballs on credit cards—even with Mom and Dad putting him up. All those dead-end projects have been expensive. Grand Man better have deep pockets.”

“Grand Man’s pockets are flapping somewhere around his shoes.”

Avery resolved to steer the conversation elsewhere. Whatever funds would trickle down from the Mandible estate was a prickly subject. Naturally Florence had never said so outright, but with the disparity in their incomes Avery wondered if when the time came she was expected to step aside and either sacrifice a substantial share to her siblings or decline her inheritance altogether. On the face of it, Avery didn’t need the money. In other words, because she’d made intelligent decisions and prospered as a consequence, she deserved to be punished? That was the lesson the quote-unquote progressive American tax system should have taught her long ago. Oh, and Florence-as-in-Nightingale surely deserved the money more, since in her most recent incarnation she was so good and kind and charitable.

But they’d both been dealt hands from the same deck. Avery had decided to marry a somewhat older intellectual heavyweight who was now a tenured professor in Georgetown University’s Economics Department; to co-purchase a handsome DC townhouse that had already appreciated in value; to establish a lucrative private practice; and to raise three bright, gifted children whom they were able to send to top-flight private schools. Meanwhile, Florence had decided to cohabit with an undereducated Mexican tour guide; to buy a tiny, ramshackle, but larcenously overpriced house in a Brooklyn neighborhood notorious when they were growing up for murderous turf wars between crack dealers; to raise a single kid born of a one-night stand who got sent to a public school where all his classes were taught in Spanish and who by the by was turning out a little strange; and professionally to plump pillows for schizophrenics. Avery wished desperately that her smart, savvy, ferociously hard-working sister—who was the real survivor of the family, not Jarred—would find a calling that put her talents to better use, and at least Esteban seemed a stand-up guy. But Florence’s dismal situation—particularly awkward for the eldest—still wasn’t Avery’s fault. Surely circumstances Avery had gone to great efforts to arrange for herself shouldn’t oblige her to feel so guilty every time they talked.

Yet the diversionary topic she raised next proved anything but neutral. “Hey, did you hear about the country-code kerfuffle?”

“Yeah, all the staff at the shelter thought it was hilarious that anybody cares. Though I’m sure this could keep Fox News foaming at the mouth for the rest of the year.”

“Well, the country code for the States has been one ever since there were country codes, right?” Avery said. “For some people, it’s symbolic.”

“Symbolic of what? We’re number one? If it means anything at all, the very fact we’ve been one forever is reason to give the dopey code to someone else for a while.”

“You sound pretty exercised, given this is an issue that you supposedly don’t care about. And it must mean something to the Chinese, or they wouldn’t have put up such a stink about swapping codes.”

“Sometimes the best thing to do when one party flies into a snit,” Florence said, “is to give them what they want. Especially if it doesn’t cost you anything but banging a few digits into a computer. This is the kind of concession you can make for free and down the road trade for something that matters.”

“Or it’s the kind of concession that sets a precedent for a whole bunch of other concessions down the road, in which case it does matter. One patient today said she felt ‘humiliated.’”

“Most Americans live in America,” Florence said. “They hardly ever enter their own country code. So unless she fleXts home from abroad all the time, your patient is never going to be actively ‘humiliated’ in the course of an ordinary day. It’s just like that hoo-ha about press two for English. Is it any harder to press two than one?”

“Let’s not get into that again. You know I thought reversing that convention was outrageous.”

“It was a generous gesture that once again cost nothing. For Lats, that two represented second-class. It was a small change that made immigrants and their descendants feel included.”

“What it made them feel is triumphant—”

“Watch it,” Florence said. “There are red lines.”

Florence’s living with a Real Live Mexican had given her airs. She was now an honorary member of a minority so enormous that it would soon lose claim to the label. A watershed to which Avery was greatly looking forward. In her practice, she urged all her patients to embrace a sensation of specialness—but that very strong sense of identity, of belonging, of proud laying claim to one’s own remarkable, particular heritage, was specifically denied the majority in this country, with a conspicuous host of achievements to be proud of. So maybe when white folks were a minority, too, they’d get their own university White Studies departments, which could unashamedly tout Herman Melville. Her children would get cut extra slack in college admissions regardless of their test scores. They could all suddenly assert that being called “white” was insulting, so that now you had to say “Western-European American,” the whole mouthful. While to each other they’d cry, “What’s up, cracker?” with a pally, insider collusion, any nonwhites who employed such a bigoted term would get raked over the coals on CNN. Becoming a minority would open the door to getting roundly, festively offended at every opportunity, and the protocol for automated phone calls would get switched back.

Esteban exclaimed off-screen, “What did I tell you? Should have opened the flood gates while we had the chance!”

Florence shouted over her shoulder, “Willing! Go to Green Acre and grab all the bottled water you can! Esteban will be right behind you—and bring the cart!”

“Okay, okay,” the boy said behind her. “I know the drill. But you know I’ll be too late. Everybody with a car is faster.”

“Then run.”

“Not another one,” Avery said.

Florence turned back to the screen with a sigh. “The worst thing about a dryout is never knowing how long it will last. The water could be back on in an hour, or it could be off for a week. At least we’ve installed some rain barrels out back. The water’s not potable, but it helps with the toilet. I’ve got some used bottles filled with tap, but it gets awfully stale. So I hope Willing and Esteban score. It’s always such a free-for-all in the water aisle. We’re lucky it’s on the late side. Some people won’t have noticed yet. Fuck, I hate to say it, but Esteban was right. I haven’t had a shower in eight days. Should have grabbed one when I got home.”

“Is it any clearer what the problem is? Not bloggy speculation. Real information.”

“Real information, what’s that?” Florence snorted. “Though even the bonkers-osphere doesn’t contest that out west the problem is drained aquifers and drought. Here, it’s more up for grabs. There may be supply problems upstate. Obviously, the Caliphate’s sabotage of Tunnel Three hasn’t helped. Lots of people claim it’s decrepit infrastructure, massive leaks. And you know what I think it is.”

“Yes, I know what you think it is.” Being on camera, Avery suppressed an eye roll. It was fashionable to observe that in an age absent rigorous investigative reporting people believed whatever suited them. Their father made this clichéd point incessantly. Yet as far as Avery could tell, people had always conceived an opinion first and assembled supporting evidence at their leisure, as they might purchase an outfit and later acquire accessories to match. So naturally Florence blamed fracking. It suited her.

The front door slammed. “Hey,” Lowell said.

“Hey! I’m talking to Florence.”

“Well, wrap it up, would you?”

He was routinely self-important, but the irritability was odd. “When I’m good and ready!”

“That’s okay,” said Florence. “I’ve got to haul rainwater to the toilet. Bye, puppet.”

Alas, at forty-eight her husband’s quarter-inch stubble no longer looked hip but seedy, and his longish graying hair cut in once-trendy uneven lengths now made him appear disheveled. Avery should think of a way of telling him so, if not in so many words. For an economist, he’d always been flashy and downtown—a snappy, daring dresser with a loose-limbed swagger that attracted acolytes at Georgetown. That sleek dove-gray suit was cutting-edge—cuffless and collarless, with high-waisted slacks and a long tunic reaching just above the knee. His shoes this evening were bright pink. But it was risky to style your image around being young. Lowell looked like someone who thought he was young, and wasn’t.

“Mojo, yo, turn on the TV!” Lowell commanded. The voice-activated household management system had recently developed a glitch, and was forever informing Avery they were out of milk. Before she disabled the function, the program had kept ordering milk from the supermarket until they were drowning in it. Now the system was getting flakier still: after Lowell’s instruction, she heard the dishwasher come on in the kitchen.

“Notice how everything goes wrong at once?” Lowell despaired. “It’s what I was just explaining to that pea-brain Mark Vandermire. Same thing happens in economics. Little crap imploding all over the place at the same time makes it seem as if the failures are connected. But they aren’t necessarily. It’s just some sort of karmic … clumping.”

“You may have another paper there. Karmic Clumping is catchy.” She handed him the dusty television remote. “Fortunately we can override. Ellen’s Mojo down the street won’t switch to manual, and when it goes freaky they can’t even boil water.”

Lowell plopped despondently onto the sofa. Rather than turn on the news, he tapped the means for doing so against his knee.

“Want anything to eat?”

“Glass of that wine you’re drinking. But I’m afraid if I ask Mojo for a BLT, it’ll turn on the sprinklers. Or set the house on fire.”

When she handed him the glass, he asked, “So—you up on the latest?”

“In that I don’t know what you’re referring to, probably not.”

“The bond auction this afternoon.”

“This is France again?”

“No, US Treasury. Look, I don’t think it’s a big deal. But the bid-to-cover ratio was weirdly poor. Roachbar, in fact: 1.1. And the yield on a ten-year note went to 8.2 percent.”

“That sounds high.”

“High? It doubled. Still, all I see is an accidental confluence of arbitrary forces.”

“Karmic clumping.”

“Yeah. You’ve got France unable to completely roll over a tranche of maturing debt—but Germany and the ECB swept in right away, so it’s not as if they’re about to close the Eiffel Tower for lack of funds. Messed with some heads, that’s all. As for Barclay’s in the UK, the official word is that Ed Balls’s government can’t bail them out this time, but that’s a strategic pose. I bet they find enough ten-P pieces tucked into the crevices of Downing Street sofas to keep the bank from going to the wall. Then yesterday a couple of skittish hedge funds in Zurich and Brussels reduced their dollar positions to basically zero and moved into gold. Let them. They’ll be using shiny rocks for paperweights when gold drops right back down.”

“It’s up?”

“For now! You know gold. It’s always ping-ponging all over the place. Unless you’re really canny about playing the highs and lows, it’s a ludicrous investment.”

“Why do I get the nagging impression that you’re not having this conversation with me? You keep arguing, one hand clapping. I’m not arguing back.”

“Sorry. I did get into an argument, with that boomerpoop Vandermire. Because, okay, the bond auction today, it’s—unfortunate. At the moment, foreign demand for US debt is low—but there are completely unrelated reasons for backing off US debt instruments in a variety of different countries that just happen to be coinciding. Here, the market is hopping; investors can find higher yields in the Dow than in dumpy Treasury securities. Interest rates aren’t likely to stay anywhere near 8.2 percent and this is probably a one-time spike. Jesus, in the 1980s, Treasury bond interest careened to over 15 percent. Bonds paid over 8 percent as recently as 1991—”

“That’s not very recent.”

“My point is, there’s no reason to get hysterical!”

“Then don’t say that hysterically.”

“It’s the panic over the interest-rate spike that’s the problem. Imbeciles like Vandermire—oh, and guess where he was headed when I ran into him in the department? MSNBC. He’d lined up back-to-back interviews on all the main stations—Fox, Asia Central, RT, LatAmerica …”

“You jealous?”

“Hell, no. Those shows are a pain in the butt. With hyper-res, they slather on the makeup an inch thick. They can’t wipe it off completely, and it stains our pillowcases. Besides, you never know whether under pressure you’ll misremember a statistic and never live it down.”

“But you’re great at it.”

His posture straightened on the sofa: compliment received. “The fear Vandermire will have peddled all night—it becomes self-fulfilling. Though he hardly sounds afraid. He’s having the time of his life. It’s like what you always say, right? This apocalyptic set—”

“I don’t ‘always’ say anything. We had that one conversation—”

“Don’t get your back up when I’m trying to agree with you. It’s just, these people forecasting the end of the world, they never seem upset by the prospect, do they? Invoking ruin, heartache, and devastation, they can barely disguise their delight. What do they think actual collapse is like, a kid’s birthday party where everyone dances in a circle singing, ‘Ashes! Ashes! We all fall down’? And they seem to assume that they themselves will be immune, sunning by the pool while cities burn on the horizon. They’re would-be voyeurs. They regard the fate of millions if not billions of real people as entertainment.”

Lowell had that look on his face of wanting to write that down.

“Florence and I are worried that Jarred’s going down a similar route. I think he’s more into eco-horror, but same idea. Although to be fair I’d hardly characterize Jarred as delighted. He’s been pretty morose.”

“Well, Vandermire is ecstatic. He loves the attention, and he’s on a high of having been supposedly right all along. ‘Unsustainable! The national debt is unsustainable!’ If I heard him say the word unsustainable one more time this afternoon I’d have punched him in the nose. The functional definition of unsustainable is that-which-is-not-sustained. If you can’t keep something up, you don’t. After all that noise twenty years ago about the deficit, the melodramatic shutdowns of government over raising the debt ceiling, and what’s happened? Nothing. At 180 percent of GDP—which Japan proved was entirely doable—the debt has been sustained. It is therefore, ipso facto, sustainable.”

“Don’t let Vandermire get to you, then. If he’s off the beam, he’ll soon look as dumb as you think he is.”

“His sort of loose, inflammatory talk is dangerous. It undermines confidence.”

“Confidence, shmonfidence. What’s it matter if a few rich investors get edgy?”

“Money is emotional,” Lowell pronounced. “Because all value is subjective, money is worth what people feel it’s worth. They accept it in exchange for goods and services because they have faith in it. Economics is closer to religion than science. Without millions of individual citizens believing in a currency, money is colored paper. Likewise, creditors have to believe that if they extend a loan to the US government they’ll get their money back or they don’t make the loan in the first place. So confidence isn’t a side issue. It’s the only issue.”

The trouble with being a professor is that when you pontificate for a living it’s hard to cut the crap once you get back home. Avery was used to it, though she didn’t find Lowell’s rants quite as enchanting as when they first got married.

“You know, most of the other doom mongers like Vandermire are also gold bugs,” Lowell resumed. “Honestly, hanging on to a decorative metal as the answer to all our prayers, it’s medieval—”

“Don’t start.”

“I’m not starting. But I don’t know why Georgetown hired that jackass. He’s meant to be a token of the faculty’s ideological ‘breadth,’ but that’s like claiming, ‘We have academic breadth because some of our professors are smart and the others are nitwits.’ The gold standard was put to rest sixty years ago, and nobody’s missed it. It was clunky, it constrained the tools available to central banks to fine-tune the economy, and it artificially limited the monetary base. It’s antiquated, superstitious, and sentimental. What the gold bugs never concede? Now that the metal has almost no real utility in and of itself, it’s therefore just as artificial a store of value as fiat currencies, or cowrie shells.”

Avery studied her husband. Maybe he’d refrained from turning on the news because he was afraid of encountering his bête noire Mark Vandermire. Or maybe he was afraid of the news itself. “You seem worried.”

“All right—a little.”

“But I know you. So here’s the question: are you worried about what’s actually happening? Because I think you’re more worried about being wrong.”

Kicking himself for that third glass of wine with Avery, Lowell got an early start the next morning with a muddy head. Skipping his usual compulsive glance at the one news website he marginally trusted, he decided to grab coffee at the department—even if it was mostly a sassafras-pit substitute; in Lowell’s private view, the biggest agricultural catastrophe in recent years wasn’t soaring commodity prices for corn and soy but the widespread dieback of the Arabica bean crop, making a proper latte the price of a stiff Remy. Driven more than ever to advocate for educated, creative, modern economics now that the likes of Vandermire would have everyone trading wampum with an abacus, he wanted to make progress on his paper on monetary policy before his 10 a.m. course, History of Inflation and Deflation. The class had hit Industrial Revolution Britain, nearly a century of persistent deflation during which the blasted country did nothing but prosper, which always put Lowell in a bad mood.

On his walk to the Metro, the sidewalks of Cleveland Park were busy for such an early hour. Though the sky at sunrise was clear, pedestrians had the huddled, scurrying quality that crowds assume in the rain. One woman quietly crying didn’t surprise him, but two did, and the next weeper was male. While Lowell didn’t by policy wear his fleX while strolling a handsome city whose sights he preferred to take in, his fellow Washingtonians routinely wrapped theirs on a wrist or hooked one on a hat brim. Yet it was very odd for so many pedestrians to be conducting audio phone calls. True, since the Stonage a handful of purist kooks had boycotted the internet altogether, and that atavistic bunch jabbered ceaselessly because talking was the only way those throwbacks could communicate. For everyone else with a life, the phone call was by consensus so prohibitively invasive that a ringtone was frightening: clearly, someone had died.

As he descended the long gray steps of his local station, the faces of scuttling commuters displayed an unnervingly uniform expression: wrenched, concentrated, stricken. He squeezed into the train as the doors were closing, barely wedging into the crowd. For pity’s sake, it was only 6:30 a.m.

Here, too, everyone was talking. Not to each other, of course. To fleXes. How low is it now? … Well, in London it’s only … Hitting margin calls … Buy Australian, Swiss francs, I don’t care! No, not Canadian, it’ll get dragged … Bet POTUS has already been roused from his … Stop-loss … Crossed stop-loss two hours ago … Stop-loss …

Even by Washington standards, Lowell Stackhouse was exceptionally averse to getting news everyone else was in on already, and after thirty seconds of this murmurous churn he’d heard enough. He whipped the fleX from his pocket, stiffened it to palm-size, and went directly to kind-of-trustworthy Bloomberg.com: DOLLAR CRASHES IN EUROPE.

chapter three (#ulink_4675fe6b-6065-54be-a534-8dde4d45e4c7)

Waiting for the Dough (#ulink_4675fe6b-6065-54be-a534-8dde4d45e4c7)

In the most ordinary of times, Carter Mandible would drive up to New Milford debating to what degree he felt guilty about dreading a visit with his own father. Why, most people his age would strain to extend themselves to the rarefied realm of ninety-seven, even if Douglas Mandible didn’t subject his son to the additional trials of feeblemindedness. Rather, Carter sometimes wished that his father showed more signs of mental fatigue, which might excite his sympathy, and lay grudges to rest. One of those grudges being first and foremost that the old man was still alive.

Oh, Carter never actively wished that his father would die. He was entirely sure—he was fairly sure—that when the time came he would be felled by the customary measure of filial grief. Friends had warned that the loss always hits you harder than you expect. But that was a discovery for which he’d been more than ready for fifteen years.

It was also standard on the two-hour trip from Brooklyn—this leafy section through Connecticut was pleasant—for Carter to question his motivations for these visits. With an eye to the long view, you naturally dote on an elderly parent as a subtly selfish prophylactic: to be able to assure yourself, on receipt of that fatal phone call, that you’d been devoted. Sometimes being a shade more attentive than you’re quite in the mood for can prevent self-excoriation down the line. After all, old people have a horrible habit of kicking it right after you ducked seeing them at the last minute with an excuse that sounded fishy, or on the heels of a regrettable encounter in which you let slip an acrid aside. To be dutiful without fail is like taking out emotional insurance.

Yet in Carter’s case, the self-interest was crassly pecuniary. Did he keep in his father’s good graces with monthly runs to the Wellcome Arms only to safeguard his inheritance from, say, a rash or spiteful late-life impulse to endow a chair at Yale? He’d never know. Worse, his father would never know, and might not ever feel confidently cherished for himself. A family fortune introduced an element of corruption. While Carter might sentimentalize the ideal world in which he spent as much time as possible with Douglas E. Mandible because he loved his father, and enjoyed his father’s company, and was resolved to make the most of his father’s blessedly extended lifespan while he still could, the money was an inescapable contaminant, and it wasn’t going to go away.

Or in theory it wouldn’t go away.

For this was not the most ordinary of times.

While it was certainly usual for Carter to chafe that by the time he came into the legacy he’d be too old to spend it, this afternoon that exasperation rose to a frenzy. He and Jayne still lived in the same modest, increasingly disheveled Carroll Gardens row house—brick, not brownstone. It was finally paid off, but for years the mortgage was a stretch. He and Jayne did get to Tuscany in 2003—a first proper vacation, in their early forties! But they’d always planned on Japan. Now that Jayne was so fearful that she’d rarely leave the house, adventures farther afield than Sahadi’s on Atlantic Avenue were out of the question. On one charge, newer cars would make it to Canada; this ten-year-old BeEtle couldn’t get past Danbury. Once he got that post at the Times he was already sixty, by which time America’s shrinking “paper of record,” having already stooped to selling creative writing courses and colonial knickknacks, was snarfing up desperate aging journalists for pocket change. His pension was farcical. If they might free up some equity by downsizing in the brief window during which their youngest had pretended to leave home, that meant finding someplace smaller and meaner and more depressing. Great.

Yet a breezy, no-cares existence had been in the pipeline all his life. The money was stuck further up the system, like a wad of the disposable diapers you’re told never to flush. Meanwhile, awaiting his birthright had suspended him in an extended adolescence. This state of decades-long deferral presaged when his real life would begin. He was sixty-nine. Real life would be short.

What Carter craved was not so much furniture and electronics, cruises and wine-tasting tours—whatever he might buy—but a feeling. A sensation of ease and liberation, of generosity and savor, of possibility and openness, of whimsy and humor and joy. Granted, he expected too much from mere money, but he’d be happy to find that out, too. Relieved of this endless waiting, he would embrace even a reputably adult disillusionment. Because he still felt like a kid. And now that theoretical Valhalla in which he and Jayne could leave the heating jacked up to sixty-eight the whole night through, or make an airy fresh start on a wide-skied ranch in Montana where Jayne might get over the terror she associated with Carroll Gardens, well—in the last few days, that future had, very probably, gone to hell.

For this last week was the most historically savage of his experience, and that was counting 9/11 and the Stone Age. As for the latter, sure, the power went out, and there was looting of course, including of Jayne’s chichi delicatessen on Smith Street, from whose gratuitous destruction she had yet to recuperate. Traffic lights going black resulted in a host of dreadful pile-ups. He could skip rehearsing all those airline disasters again, the train wrecks, the poignant human-interest packages about cardiac patients whose pacemakers began beating double-time, like an invigorating change-up in a Miles Davis recording. Parts of the country had no water, though that was good practice for the dryouts to come. Telecommunications and national defense systems ceased to function, even if in Carter’s view America’s vaunted “defense” had long put the country in the way of more munitions than it deflected. Understandably, then, for Florence, Avery, and Jarred, 2024 constituted the direst of calamities. But Carter hailed from a different generation—one raised locating phone numbers in scrawled paper diaries and tracking down zip codes in fat directories from the post office, painstakingly diluting encrusted Liquid Paper with plastic pipettes from tiny overpriced bottles of thinner and later upgrading with outsize gratitude to the self-correcting ribbons of IBM Selectrics, flicking through yellowed rectangles in the long wooden drawers of card catalogs and looking up articles in the Readers’ Guide to Periodical Literature in the library. There was only so gravely he was likely to rate going without the internet for three weeks.

Albeit eerily invisible, eerily silent, this last week’s turmoil was of another order. The Stone Age produced immediate, palpable consequences: the lights wouldn’t go on, food rotted in the fridge, and none of the few stores remaining open carried milk. Throughout this latest mayhem nothing changed. A conventional number of cars on I-84 were doing the usual five miles per hour over the speed limit. The sky was mockingly clear. Exiting for a recharge, Carter didn’t have to swerve around bodies littering the ramp, or duck to avoid gunfire. Its lot half-full, Friendly’s was continuing to sell maple-walnut cones and SuperMelts. Strolling between chargers and convenience stores, none of Carter’s fellow motorists appeared hurried or flustered. This whole placid commercial stretch testified to the fact that the folks most affected by the week’s historical bad weather weren’t temperamentally inclined to pitch rocks through plate glass. One such under-violent character was bound to be his father.

If you believed its literature, the Wellcome Arms was the most luxuriously equipped assisted-living facility in the United States. The high-tech gym was really a come-on for prospective tenants, promising retirement as renewal, as the unfettered free time to step into the trim, fit incarnation you’d always been too busy to manifest—until the shine wore off and residents were confronted with the odious exertion of using the machines. The joint actually kept horses, though Carter had never seen anyone ride one. Replete with water therapists and massage jets, the pool saw more traffic, since a proportion of the residents could still float. It went without saying that the home provided the medical facilities of a top-flight private hospital; given Wellcome’s astronomical charges, it was worth the institution’s while to keep its clients, however nominally, in this world.

Although Douglas Mandible would not commonly be parted from his fleX before the 4 p.m. close of the New York Stock Exchange, pulling into Visitor Parking, Carter spotted his father on the nearest tennis court. Douglas was once a hard-hitting, cutthroat singles player, who would risk stroke or seizure to retrieve a skittering down-the-line—in the same fashion that as an equally cutthroat literary agent he had pulled out all the stops to score celebrated novelists. Yet in advanced age he’d refined a very different game, whereby he ran this much-younger opponent (late seventies, Carter guessed) from corner to corner. Barely returning the shot, the other guy would blob his own right to Douglas’s feet, and Pop could keep the ball in play without moving more than five inches in any direction. It was the same hyper-efficient, energy-conserving manipulation that Douglas could employ to effortlessly control his family without leaving his chair.

With a wicked crosscourt sharding out of the service box, Douglas dispatched the point in the spirit of simply having had enough. Carter didn’t flatter himself that his father had cut the point short because he’d spied his son in the parking lot. Having given notice of this visit, Carter was right on time. Had Pop given a damn about not keeping his son waiting, he wouldn’t have been playing tennis in the first place.

Douglas made a show of mopping his face and waved at Visitor Parking with the towel. His figure was closer to scrawny than sleek, but his bearing remained debonair. The mane of blazing white hair was more spectacular than the younger auburn version. In October, he sported a leathery tan. While spinal compression had shaved a good two inches off his height, that still left the patriarch a touch taller than his only son. Age had scored his long face with an expression of drollery once fleeting and now ceaseless. He would look dryly amused in his sleep.