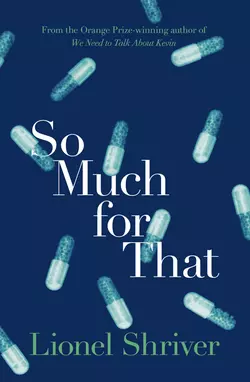

So Much for That

Lionel Shriver

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 152.86 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: An extraordinary novel from the Orange Prize winning author of ‘We Need to Talk About Kevin’.What do you pack for the rest of your life?Shepherd Knacker is bored with his humdrum existence. He′s sold his successful handy-man business for a million dollars and is now ready to embark on his ′Afterlife′ – a one way ticket to a small island off the coast of Africa. He tries to convince his wife Glynis to come with him, but she laughs off the idea as preposterous.There′s no way she′ll let Shepherd uproot the family to some far-flung African island.When Glynis is diagnosed with an extremely rare and aggressive form of cancer, Shepherd′s dreams of an exotic adventure are firmly put on hold. He devotes himself to caring for his sick wife, watching her fade before his eyes.Shepherd′s best friend Jackson knows all too well about illness. His sixteen year old daughter has spent her life dosed up on every treatment going while he and his wife Carol feed their youngest daughter sugar pills so she won′t feel left out. But then Jackson undergoes a medical procedure of his own which has devastating consequences …So Much For That is a deeply affecting novel, told with Lionel Shriver′s trademark originality, intelligence and acute perception of the human condition.