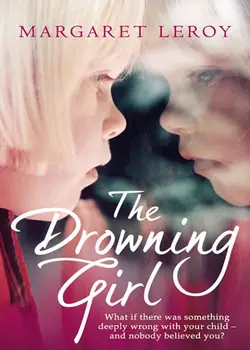

The Drowning Girl

Margaret Leroy

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 463.36 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Young single mum Grace is drowning. Her little girl Sylvie is distant, troubled and prone to violent tantrums which the child psychiatrists blame on Grace. But Grace knows there’s something more to what’s happening to Sylvie. There has to be.Travelling from the London suburbs to the west coast of Ireland, Grace and Sylvie embark on a journey of shocking discovery, forcing Grace to question everything she believes in and changing both their lives forever.‘Margaret Leroy writes with candour and intelligence, capturing the menace of suddenly finding that the world may not be at all as you’ve thought it’ Helen Dunmore ‘Margaret Leroy writes like a dream’ Tony Parsons