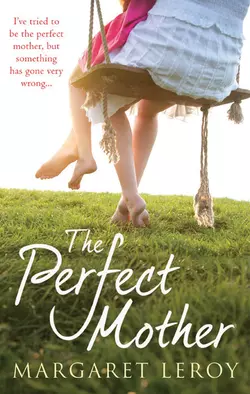

The Perfect Mother

Margaret Leroy

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 458.46 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: What really goes on behind closed doors?Catriona has the life she’s always dreamed of: a loving husband, a delightful step-daughter and her own precious little girl, Daisy. When Daisy begins to feel poorly, Catriona seeks help and, in doing so, is forced to look to the past and her own dark and fractured childhood.When Cat is accused of an unspeakable crime, she begins to realise that the life she has now is more fragile than she could ever have imagined.“Margaret Leroy writes like a dream” Tony Parsons “I was eager to find out what happened next. I dreaded the worst and I hoped for the best – and I won’t tell you which happens” New York Times