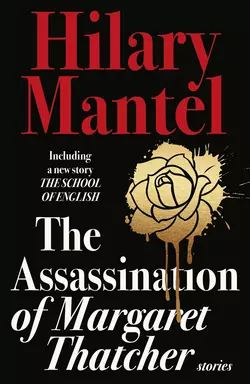

The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher

Hilary Mantel

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 853.37 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Nothing is as it seems. Childhood cruelty is played out behind bushes. Both the living and the dead commute to Waterloo station. Staying in for the plumber turns into a potentially fatal waiting game. And in ‘The School of English’, panic grips a household behind the stucco facade of a Notting Hill mansion. All that is clear and constant in these bracingly subversive stories is Hilary Mantel’s distinctive style and wit.