Hilary Mantel Collection: Six of Her Best Novels

Hilary Mantel

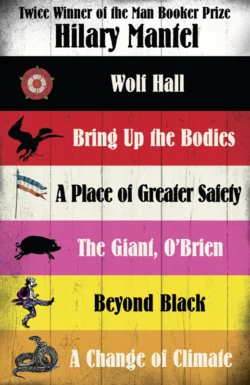

Our greatest living writer.Six of her best novels.Hilary Mantel is the first British writer to win two Man Booker Prizes. This set brings together six of her greatest novels – the first two books in her Thomas Cromwell trilogy, the record-setting Man Booker prize-winners ‘Wolf Hall’ and ‘Bring Up the Bodies’.’ A Place of Greater Safety’ is an epic of Revolutionary France. The darkly comic ‘Beyond Black’ is a lively tale of a psychic and the impish spirits she summons. ‘The Giant, O’Brien’ tells the story of the legendary Charles Byrne and the surgeon who wanted his bones. And a family seeks refuge after an unfortunate African sojourn in ‘A Change of Climate’.For fans of the best literature eager to discover one of our greatest writers, this collection is essential reading.

THE HILARY MANTEL COLLECTION

Hilary Mantel

Table of Contents

Cover (#ua8f1a767-09e1-59c8-b6c3-afde48d6ea9f)

Title Page (#u6ee92133-ce11-5998-b0ff-a5e140ad44c0)

Wolf Hall (#ue45c6146-2852-5397-9c8b-e6699d4d5ca2)

Bring Up The Bodies (#ue89883e8-89d7-5073-ba81-5dc7e99688d0)

A Place of Greater Safety (#ud8950a03-3e41-5941-8638-44380ef1a844)

The Giant, O’Brien (#u2b7a02f6-5233-502a-a08c-d01dfb4043ea)

Beyond Black (#u69c968de-00e3-5f48-8b92-e60f656973e9)

A Change of Climate (#u7bce98ce-c2f7-505c-ae6d-1ca6b9dc2146)

About the Author (#ua84b9f27-3c04-50fe-a751-62c8ccfc0589)

By the Same Author (#u1f157f70-9a86-5625-b5bb-8cc069294257)

Copyright (#ue5a914a6-b691-5ff8-b929-f6634655a812)

About the Publisher (#u0e4cb29b-45ab-5d53-82be-790930367f9e)

HILARY MANTEL

WOLF HALL

Dedication (#uca30972e-631e-51d6-b813-86d33a036c56)

To my singular friend Mary Robertson this be given.

CONTENTS

Cover (#u304df52c-68e8-5bff-b64a-9ac2bdf5af2d)

Title Page (#ue45c6146-2852-5397-9c8b-e6699d4d5ca2)

Dedication (#udf352027-271e-5682-855c-a434c4ba29e1)

Cast of Characters (#u5a112eb1-86d3-5684-a204-a28cb74b6351)

Family Trees (#ueecedf2e-d717-5042-95eb-fc982c7947d9)

Epigraph (#ub64d395f-4409-595c-984b-f6fc6f7ffc07)

Part One (#u259af688-60f5-55ed-9351-bd26a63e17f7)

Chapter I - Across the Narrow Sea. 1500 (#ud3498a9c-a9b8-501a-ad5d-d051ddb93e06)

Chapter II - Paternity. 1527 (#u7fca9032-124c-57bb-9dcd-020e2ee3d77d)

Chapter III - At Austin Friars. 1527 (#uc2c8c2ff-71df-547b-8957-2f49755b360d)

Part Two (#u71cd298b-5e7e-58bd-8f68-5ef8744b6b5e)

Chapter I - Visitation. 1529 (#ud0ac9e4e-73c5-5102-84e4-8292cb57ea21)

Chapter II - An Occult History of Britain. 1521–1529 (#u877b4eba-d374-5997-b91d-728c3bfc7738)

Chapter III - Make or Mar. All Hallows 1529 (#u5ffbd17b-30de-5031-8d33-2fadd9fab742)

Part Three (#ub254d0d5-215f-588e-8a14-76010ac99aa7)

Chapter I - Three-Card Trick. Winter 1529–Spring 1530 (#u8eb59641-9be8-5e94-9130-051db8ee1439)

Chapter II - Entirely Beloved Cromwell. Spring–December 1530 (#ua0be53ef-97d1-52a6-a1a4-5b64d720bfc8)

Chapter III - The Dead Complain of Their Burial. Christmastide 1530 (#udba96b8c-93ba-511b-839c-f61c588ca33d)

Part Four (#u2e557247-f9bd-5935-94b3-750987547232)

Chapter I - Arrange Your Face. 1531 (#ub9d26a78-bed2-519b-abac-aa6d30b6ac6a)

Chapter II - ‘Alas, What Shall I Do For Love?’ Spring 1532 (#u10122ce5-a767-548b-9212-3821a5b79691)

Chapter III - Early Mass. November 1532 (#u7932d12e-4888-5e8e-87f1-cbf7da02bf0d)

Part Five (#uaf3c0bce-c1eb-5c49-8aec-59896b75b2d7)

Chapter I - Anna Regina. 1533 (#u5bde4bec-d161-58ee-ba20-c643a14499ca)

Chapter II - Devil's Spit. Autumn and winter 1533 (#u7b9928ba-f32d-59f9-b3f2-6f7ec0c55eba)

Chapter III - A Painter's Eye. 1534 (#u44d12a47-985c-5ff9-9734-4db8dcc56bdb)

Part Six (#u7ac2d31f-52d4-5aeb-993b-16d91b1e13e4)

Chapter I - Supremacy. 1534 (#uc8ae6061-3243-52d7-ba0a-177b7b72d11d)

Chapter II - The Map of Christendom. 1534–1535 (#udeb77e36-952f-542d-a435-ba369c747b76)

Chapter III - To Wolf Hall. July 1535 (#u8c14d3ec-9996-51be-ab4e-af088ad42d86)

Author's Note (#ucd21193f-cf92-5d17-898f-83d49f9b35cb)

Acknowledgements (#ud8aa3de6-ff56-59a7-8744-cf591e888bb9)

Copyright (#u2fc638ae-85dd-5dc6-a527-e55727e889db)

CAST OF CHARACTERS (#uca30972e-631e-51d6-b813-86d33a036c56)

In Putney, 1500

Walter Cromwell, a blacksmith and brewer.

Thomas, his son.

Bet, his daughter.

Kat, his daughter.

Morgan Williams, Kat's husband.

At Austin Friars, from 1527

Thomas Cromwell, a lawyer.

Liz Wykys, his wife.

Gregory, their son.

Anne, their daughter.

Grace, their daughter.

Henry Wykys, Liz's father, a wool trader.

Mercy, his wife.

Johane Williamson, Liz's sister.

John Williamson, her husband.

Johane (Jo), their daughter.

Alice Wellyfed, Cromwell's niece, daughter of Bet Cromwell.

Richard Williams, later called Cromwell, son of Kat and Morgan.

Rafe Sadler, Cromwell's chief clerk, brought up at Austin Friars.

Thomas Avery, the household accountant.

Helen Barre, a poor woman taken in by the household.

Thurston, the cook.

Christophe, a servant.

Dick Purser, keeper of the guard dogs.

At Westminster

Thomas Wolsey, Archbishop of York, cardinal, papal legate, Lord Chancellor: Thomas Cromwell's patron.

George Cavendish, Wolsey's gentleman usher and later biographer.

Stephen Gardiner, Master of Trinity Hall, the cardinal's secretary, later Master Secretary to Henry VIII: Cromwell's most devoted enemy.

Thomas Wriothesley, Clerk of the Signet, diplomat, protégé of both Cromwell and Gardiner.

Richard Riche, lawyer, later Solicitor General.

Thomas Audley, lawyer, Speaker of the House of Commons, Lord Chancellor after Thomas More's resignation.

At Chelsea

Thomas More, lawyer and scholar, Lord Chancellor after Wolsey's fall. Alice, his wife.

Sir John More, his aged father.

Margaret Roper, his eldest daughter, married to Will Roper.

Anne Cresacre, his daughter-in-law.

Henry Pattinson, a servant.

In the city

Humphrey Monmouth, merchant, imprisoned for sheltering William Tyndale, translator of the Bible into English.

John Petyt, merchant, imprisoned on suspicion of heresy.

Lucy, his wife.

John Parnell, merchant, embroiled in long-running legal dispute with Thomas More.

Little Bilney, scholar burned for heresy.

John Frith, scholar burned for heresy.

Antonio Bonvisi, merchant, from Lucca.

Stephen Vaughan, merchant at Antwerp, friend of Cromwell.

At court

Henry VIII.

Katherine of Aragon, his first wife, later known as Dowager Princess of Wales.

Mary, their daughter.

Anne Boleyn, his second wife.

Mary, her sister, widow of William Carey and Henry's ex-mistress.

Thomas Boleyn, her father, later Earl of Wiltshire and Lord Privy Seal: likes to be known as ‘Monseigneur’.

George, her brother, later Lord Rochford.

Jane Rochford, George's wife.

Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, Anne's uncle.

Mary Howard, his daughter.

Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, old friend of Henry, married to his sister Mary.

Mark Smeaton, a musician.

Henry Wyatt, a courtier.

Thomas Wyatt, his son.

Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond, the king's illegitimate son.

Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland.

The clergy

William Warham, aged Archbishop of Canterbury.

Cardinal Campeggio, papal envoy.

John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, legal adviser to Katherine of Aragon.

Thomas Cranmer, Cambridge scholar, reforming Archbishop of Canterbury, succeeding Warham.

Hugh Latimer, reforming priest, later Bishop of Worcester.

Rowland Lee, friend of Cromwell, later Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield.

In Calais

Lord Berners, the Governor, a scholar and translator.

Lord Lisle, the incoming Governor.

Honor, his wife.

William Stafford, attached to the garrison.

At Hatfield

Lady Bryan, mother of Francis, in charge of the infant princess, Elizabeth.

Lady Anne Shelton, Anne Boleyn's aunt, in charge of the former princess, Mary.

The ambassadors

Eustache Chapuys, career diplomat from Savoy, London ambassador of Emperor Charles V.

Jean de Dinteville, an ambassador from Francis I.

The Yorkist claimants to the throne

Henry Courtenay, Marquis of Exeter, descended from a daughter of Edward IV.

Gertrude, his wife.

Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury, niece of Edward IV.

Lord Montague, her son.

Geoffrey Pole, her son.

Reginald Pole, her son.

The Seymour family at Wolf Hall

Old Sir John, who has an affair with the wife of his eldest son Edward.

Edward Seymour, his son.

Thomas Seymour, his son.

Jane, his daughter: at court.

Lizzie, his daughter, married to the Governor of Jersey.

William Butts, a physician.

Nikolaus Kratzer, an astronomer.

Hans Holbein, an artist.

Sexton, Wolsey's fool.

Elizabeth Barton, a prophetess.

Family Trees (#uca30972e-631e-51d6-b813-86d33a036c56)

The Tudors

The Yorkist Claimants

Epigraph (#uca30972e-631e-51d6-b813-86d33a036c56)

‘There are three kinds of scenes, one called the tragic, second the comic, third the satyric. Their decorations are different and unalike each other in scheme. Tragic scenes are delineated with columns, pediments, statues and other objects suited to kings; comic scenes exhibit private dwellings, with balconies and views representing rows of windows, after the manner of ordinary dwellings; satyric scenes are decorated with trees, caverns, mountains and other rustic objects delineated in landscape style.’

VITRUVIUS, De Architectura, on the theatre, c.27BC

These be the names of the players:

PART ONE (#uca30972e-631e-51d6-b813-86d33a036c56)

I Across the Narrow Sea Putney, 1500 (#uca30972e-631e-51d6-b813-86d33a036c56)

‘So now get up.’

Felled, dazed, silent, he has fallen; knocked full length on the cobbles of the yard. His head turns sideways; his eyes are turned towards the gate, as if someone might arrive to help him out. One blow, properly placed, could kill him now.

Blood from the gash on his head – which was his father's first effort – is trickling across his face. Add to this, his left eye is blinded; but if he squints sideways, with his right eye he can see that the stitching of his father's boot is unravelling. The twine has sprung clear of the leather, and a hard knot in it has caught his eyebrow and opened another cut.

‘So now get up!’ Walter is roaring down at him, working out where to kick him next. He lifts his head an inch or two, and moves forward, on his belly, trying to do it without exposing his hands, on which Walter enjoys stamping. ‘What are you, an eel?’ his parent asks. He trots backwards, gathers pace, and aims another kick.

It knocks the last breath out of him; he thinks it may be his last. His forehead returns to the ground; he lies waiting, for Walter to jump on him. The dog, Bella, is barking, shut away in an outhouse. I'll miss my dog, he thinks. The yard smells of beer and blood. Someone is shouting, down on the riverbank. Nothing hurts, or perhaps it's that everything hurts, because there is no separate pain that he can pick out. But the cold strikes him, just in one place: just through his cheekbone as it rests on the cobbles.

‘Look now, look now,’ Walter bellows. He hops on one foot, as if he's dancing. ‘Look what I've done. Burst my boot, kicking your head.’

Inch by inch. Inch by inch forward. Never mind if he calls you an eel or a worm or a snake. Head down, don't provoke him. His nose is clotted with blood and he has to open his mouth to breathe. His father's momentary distraction at the loss of his good boot allows him the leisure to vomit. ‘That's right,’ Walter yells. ‘Spew everywhere.’ Spew everywhere, on my good cobbles. ‘Come on, boy, get up. Let's see you get up. By the blood of creeping Christ, stand on your feet.’

Creeping Christ? he thinks. What does he mean? His head turns sideways, his hair rests in his own vomit, the dog barks, Walter roars, and bells peal out across the water. He feels a sensation of movement, as if the filthy ground has become the Thames. It gives and sways beneath him; he lets out his breath, one great final gasp. You've done it this time, a voice tells Walter. But he closes his ears, or God closes them for him. He is pulled downstream, on a deep black tide.

The next thing he knows, it is almost noon, and he is propped in the doorway of Pegasus the Flying Horse. His sister Kat is coming from the kitchen with a rack of hot pies in her hands. When she sees him she almost drops them. Her mouth opens in astonishment. ‘Look at you!’

‘Kat, don't shout, it hurts me.’

She bawls for her husband: ‘Morgan Williams!’ She rotates on the spot, eyes wild, face flushed from the oven's heat. ‘Take this tray, body of God, where are you all?’

He is shivering from head to foot, exactly like Bella did when she fell off the boat that time.

A girl runs in. ‘The master's gone to town.’

‘I know that, fool.’ The sight of her brother had panicked the knowledge out of her. She thrusts the tray at the girl. ‘If you leave them where the cats can get at them, I'll box your ears till you see stars.’ Her hands empty, she clasps them for a moment in violent prayer. ‘Fighting again, or was it your father?’

Yes, he says, vigorously nodding, making his nose drop gouts of blood: yes, he indicates himself, as if to say, Walter was here. Kat calls for a basin, for water, for water in a basin, for a cloth, for the devil to rise up, right now, and take away Walter his servant. ‘Sit down before you fall down.’ He tries to explain that he has just got up. Out of the yard. It could be an hour ago, it could even be a day, and for all he knows, today might be tomorrow; except that if he had lain there for a day, surely either Walter would have come and killed him, for being in the way, or his wounds would have clotted a bit, and by now he would be hurting all over and almost too stiff to move; from deep experience of Walter's fists and boots, he knows that the second day can be worse than the first. ‘Sit. Don't talk,’ Kat says.

When the basin comes, she stands over him and works away, dabbing at his closed eye, working in small circles round and round at his hairline. Her breathing is ragged and her free hand rests on his shoulder. She swears under her breath, and sometimes she cries, and rubs the back of his neck, whispering, ‘There, hush, there,’ as if it were he who were crying, though he isn't. He feels as if he is floating, and she is weighting him to earth; he would like to put his arms around her and his face in her apron, and rest there listening to her heartbeat. But he doesn't want to mess her up, get blood all down the front of her.

When Morgan Williams comes in, he is wearing his good town coat. He looks Welsh and pugnacious; it's clear he's heard the news. He stands by Kat, staring down, temporarily out of words; till he says, ‘See!’ He makes a fist, and jerks it three times in the air. ‘That!’ he says. ‘That's what he'd get. Walter. That's what he'd get. From me.’

‘Just stand back,’ Kat advises. ‘You don't want bits of Thomas on your London jacket.’

No more does he. He backs off. ‘I wouldn't care, but look at you, boy. You could cripple the brute in a fair fight.’

‘It never is a fair fight,’ Kat says. ‘He comes up behind you, right, Thomas? With something in his hand.’

‘Looks like a glass bottle, in this case,’ Morgan Williams says. ‘Was it a bottle?’

He shakes his head. His nose bleeds again.

‘Don't do that, brother,’ Kat says. It's all over her hand; she wipes the blood clots down herself. What a mess, on her apron; he might as well have put his head there after all.

‘I don't suppose you saw?’ Morgan says. ‘What he was wielding, exactly?’

‘That's the value,’ says Kat, ‘of an approach from behind – you sorry loss to the magistrates’ bench. Listen, Morgan, shall I tell you about my father? He'll pick up whatever's to hand. Which is sometimes a bottle, true. I've seen him do it to my mother. Even our little Bet, I've seen him hit her over the head. Also I've not seen him do it, which was worse, and that was because it was me about to be felled.'

‘I wonder what I've married into,’ Morgan Williams says.

But really, this is just something Morgan says; some men have a habitual sniffle, some women have a headache, and Morgan has this wonder. The boy doesn't listen to him; he thinks, if my father did that to my mother, so long dead, then maybe he killed her? No, surely he'd have been taken up for it; Putney's lawless, but you don't get away with murder. Kat's what he's got for a mother: crying for him, rubbing the back of his neck.

He shuts his eyes, to make the left eye equal with the right; he tries to open both. ‘Kat,’ he says, ‘I have got an eye under there, have I? Because it can't see anything.’ Yes, yes, yes, she says, while Morgan Williams continues his interrogation of the facts; settles on a hard, moderately heavy, sharp object, but possibly not a broken bottle, otherwise Thomas would have seen its jagged edge, prior to Walter splitting his eyebrow open and aiming to blind him. He hears Morgan forming up this theory and would like to speak about the boot, the knot, the knot in the twine, but the effort of moving his mouth seems disproportionate to the reward. By and large he agrees with Morgan's conclusion; he tries to shrug, but it hurts so much, and he feels so crushed and disjointed, that he wonders if his neck is broken.

‘Anyway,’ Kat says, ‘what were you doing, Tom, to set him off? He usually won't start up till after dark, if it's for no cause at all.’

‘Yes,’ Morgan Williams says, ‘was there a cause?’

‘Yesterday. I was fighting.’

‘You were fighting yesterday? Who in the holy name were you fighting?’

‘I don't know.’ The name, along with the reason, has dropped out of his head; but it feels as if, in exiting, it has removed a jagged splinter of bone from his skull. He touches his scalp, carefully. Bottle? Possible.

‘Oh,’ Kat says, ‘they're always fighting. Boys. Down by the river.’

‘So let me be sure I have this right,’ Morgan says. ‘He comes home yesterday with his clothes torn and his knuckles skinned, and the old man says, what's this, been fighting? He waits a day, then hits him with a bottle. Then he knocks him down in the yard, kicks him all over, beats up and down his length with a plank of wood that comes to hand …’

‘Did he do that?’

‘It's all over the parish! They were lining up on the wharf to tell me, they were shouting at me before the boat tied up. Morgan Williams, listen now, your wife's father has beaten Thomas and he's crawled dying to his sister's house, they've called the priest … Did you call the priest?’

‘Oh, you Williamses!’ Kat says. ‘You think you're such big people around here. People are lining up to tell you things. But why is that? It's because you believe anything.’

‘But it's right!’ Morgan yells. ‘As good as right! Eh? If you leave out the priest. And that he's not dead yet.’

‘You'll make that magistrates' bench for sure,’ Kat says, ‘with your close study of the difference between a corpse and my brother.’

‘When I'm a magistrate, I'll have your father in the stocks. Fine him? You can't fine him enough. What's the point of fining a person who will only go and rob or swindle monies to the same value out of some innocent who crosses his path?’

He moans: tries to do it without intruding.

‘There, there, there,’ Kat whispers.

‘I'd say the magistrates have had their bellyful,’ Morgan says. ‘If he's not watering his ale, he's running illegal beasts on the common, if he's not despoiling the common he's assaulting an officer of the peace, if he's not drunk he's dead drunk, and if he's not dead before his time there's no justice in this world.’

‘Finished?’ Kat says. She turns back to him. ‘Tom, you'd better stay with us now. Morgan Williams, what do you say? He'll be good to do the heavy work, when he's healed up. He can do the figures for you, he can add and … what's the other thing? All right, don't laugh at me, how much time do you think I had for learning figures, with a father like that? If I can write my name, it's because Tom here taught me.’

‘He won't,’ he says. ‘Like it.’ He can only manage like this: short, simple, declarative sentences.

‘Like? He should be ashamed,’ Morgan says.

Kat says, ‘Shame was left out when God made my dad.’

He says, ‘Because. Just a mile away. He can easily.’

‘Come after you? Just let him.’ Morgan demonstrates his fist again: his little nervy Welsh punch.

After Kat had finished swabbing him and Morgan Williams had ceased boasting and reconstructing the assault, he lay up for an hour or two, to recover from it. During this time, Walter came to the door, with some of his acquaintance, and there was a certain amount of shouting and kicking of doors, though it came to him in a muffled way and he thought he might have dreamed it. The question in his mind now is, what am I going to do, I can't stay in Putney. Partly this is because his memory is coming back, for the day before yesterday and the earlier fight, and he thinks there might have been a knife in it somewhere; and whoever it was stuck in, it wasn't him, so was it by him? All this is unclear in his mind. What is clear is his thought about Walter: I've had enough of this. If he gets after me again I'm going to kill him, and if I kill him they'll hang me, and if they're going to hang me I want a better reason.

Below, the rise and fall of their voices. He can't pick out every word. Morgan says he's burnt his boats. Kat is repenting of her first offer, a post as pot-boy, general factotum and chucker-out; because, Morgan's saying, ‘Walter will always be coming round here, won't he? And “Where's Tom, send him home, who paid the bloody priest to teach him to read and write, I did, and you're reaping the bloody benefit now, you leek-eating cunt.”’

He comes downstairs. Morgan says cheerily, ‘You're looking well, considering.’

The truth is about Morgan Williams – and he doesn't like him any the less for it – the truth is, this idea he has that one day he'll beat up his father-in-law, it's solely in his mind. In fact, he's frightened of Walter, like a good many people in Putney – and, for that matter, Mortlake and Wimbledon.

He says, ‘I'm on my way, then.’

Kat says, ‘You have to stay tonight. You know the second day is the worst.’

‘Who's he going to hit when I'm gone?’

‘Not our affair,’ Kat says. ‘Bet is married and got out of it, thank God.’

Morgan Williams says, ‘If Walter was my father, I tell you, I'd take to the road.’ He waits. ‘As it happens, we've gathered some ready money.’

A pause.

‘I'll pay you back.’

Morgan says, laughing, relieved, ‘And how will you do that, Tom?’

He doesn't know. Breathing is difficult, but that doesn't mean anything, it's only because of the clotting inside his nose. It doesn't seem to be broken; he touches it, speculatively, and Kat says, careful, this is a clean apron. She's smiling a pained smile, she doesn't want him to go, and yet she's not going to contradict Morgan Williams, is she? The Williamses are big people, in Putney, in Wimbledon. Morgan dotes on her; he reminds her she's got girls to do the baking and mind the brewing, why doesn't she sit upstairs sewing like a lady, and praying for his success when he goes off to London to do a few deals in his town coat? Twice a day she could sweep through the Pegasus in a good dress and set in order anything that's wrong: that's his idea. And though as far as he can see she works as hard as ever she did when she was a child, he can see how she might like it, that Morgan would exhort her to sit down and be a lady.

‘I'll pay you back,’ he says. ‘I might go and be a soldier. I could send you a fraction of my pay and I might get loot.’

Morgan says, ‘But there isn't a war.’

‘There'll be one somewhere,’ Kat says.

‘Or I could be a ship's boy. But, you know, Bella – do you think I should go back for her? She was screaming. He had her shut up.’

‘So she wouldn't nip his toes?’ Morgan says. He's satirical about Bella.

‘I'd like her to come away with me.’

‘I've heard of a ship's cat. Not of a ship's dog.’

‘She's very small.’

‘She'll not pass for a cat,’ Morgan laughs. ‘Anyway, you're too big all round for a ship's boy. They have to run up the rigging like little monkeys – have you ever seen a monkey, Tom? Soldier is more like it. Be honest, like father like son – you weren't last in line when God gave out fists.’

‘Right,’ Kat said. ‘Shall we see if we understand this? One day my brother Tom goes out fighting. As punishment, his father creeps up behind and hits him with a whatever, but heavy, and probably sharp, and then, when he falls down, almost takes out his eye, exerts himself to kick in his ribs, beats him with a plank of wood that stands ready to hand, knocks in his face so that if I were not his own sister I'd barely recognise him: and my husband says, the answer to this, Thomas, is go for a soldier, go and find somebody you don't know, take out his eye and kick in his ribs, actually kill him, I suppose, and get paid for it.’

‘May as well,’ Morgan says, ‘as go fighting by the river, without profit to anybody. Look at him – if it were up to me, I'd have a war just to employ him.’

Morgan takes out his purse. He puts down coins: chink, chink, chink, with enticing slowness.

He touches his cheekbone. It is bruised, intact: but so cold.

‘Listen,’ Kat says, ‘we grew up here, there's probably people that would help Tom out –’

Morgan gives her a look: which says, eloquently, do you mean there are a lot of people would like to be on the wrong side of Walter Cromwell? Have him breaking their doors down? And she says, as if hearing his thought out loud, ‘No. Maybe. Maybe, Tom, it would be for the best, do you think?’

He stands up. She says, ‘Morgan, look at him, he shouldn't go tonight.’

‘I should. An hour from now he'll have had a skinful and he'll be back. He'd set the place on fire if he thought I were in it.’

Morgan says, ‘Have you got what you need for the road?’

He wants to turn to Kat and say, no.

But she's turned her face away and she's crying. She's not crying for him, because nobody, he thinks, will ever cry for him, God didn't cut him out that way. She's crying for her idea of what life should be like: Sunday after church, all the sisters, sisters-in-law, wives kissing and patting, swatting at each other's children and at the same time loving them and rubbing their little round heads, women comparing and swapping babies, and all the men gathering and talking business, wool, yarn, lengths, shipping, bloody Flemings, fishing rights, brewing, annual turnover, nice timely information, favour-for-favour, little sweeteners, little retainers, my attorney says … That's what it should be like, married to Morgan Williams, with the Williamses being a big family in Putney … But somehow it's not been like that. Walter has spoiled it all.

Carefully, stiffly, he straightens up. Every part of him hurts now. Not as badly as it will hurt tomorrow; on the third day the bruises come out and you have to start answering people's questions about why you've got them. By then he will be far from here, and presumably no one will hold him to account, because no one will know him or care. They'll think it's usual for him to have his face beaten in.

He picks up the money. He says, ‘Hwyl, Morgan Williams. Diolch am yr arian.’ Thank you for the money. ‘Gofalwch am Katheryn. Gofalwch am eich busness. Wela I chi eto rhywbryd. Pobl lwc.’

Look after my sister. Look after your business. See you again sometime.

Morgan Williams stares.

He almost grins; would do, if it wouldn't split his face open. All those days he'd spent hanging around the Williamses' households: did they think he'd just come for his dinner?

‘Pobl lwc,’ Morgan says slowly. Good luck.

He says, ‘If I follow the river, is that as good as anything?’

‘Where are you trying to get?’

‘To the sea.’

For a moment, Morgan Williams looks sorry it has come to this. He says, ‘You'll be all right, Tom? I tell you, if Bella comes looking for you, I won't send her home hungry. Kat will give her a pie.’

He has to make the money last. He could work his way downriver; but he is afraid that if he is seen, Walter will catch him, through his contacts and his friends, those kind of men who will do anything for a drink. What he thinks of, first, is slipping on to one of the smugglers' ships that go out of Barking, Tilbury. But then he thinks, France is where they have wars. A few people he talks to – he talks to strangers very easily – are of the same belief. Dover then. He gets on the road.

If you help load a cart you get a ride in it, as often as not. It gives him to think, how bad people are at loading carts. Men trying to walk straight ahead through a narrow gateway with a wide wooden chest. A simple rotation of the object solves a great many problems. And then horses, he's always been around horses, frightened horses too, because when in the morning Walter wasn't sleeping off the effects of the strong brew he kept for himself and his friends, he would turn to his second trade, farrier and blacksmith; and whether it was his sour breath, or his loud voice, or his general way of going on, even horses that were good to shoe would start to shake their heads and back away from the heat. Their hooves gripped in Walter's hands, they'd tremble; it was his job to hold their heads and talk to them, rubbing the velvet space between their ears, telling them how their mothers love them and talk about them still, and how Walter will soon be over.

He doesn't eat for a day or so; it hurts too much. But by the time he reaches Dover the big gash on his scalp has closed, and the tender parts inside, he trusts, have mended themselves: kidneys, lungs and heart.

He knows by the way people look at him that his face is still bruised. Morgan Williams had done an inventory of him before he left: teeth (miraculously) still in his head, and two eyes, miraculously seeing. Two arms, two legs: what more do you want?

He walks around the docks saying to people, do you know where there's a war just now?

Each man he asks stares at his face, steps back and says, ‘You tell me!’

They are so pleased with this, they laugh at their own wit so much, that he continues asking, just to give people pleasure.

Surprisingly, he finds he will leave Dover richer than he arrived. He'd watched a man doing the three-card trick, and when he learned it he set up for himself. Because he's a boy, people stop to have a go. It's their loss.

He adds up what he's got and what he's spent. Deduct a small sum for a brief grapple with a lady of the night. Not the sort of thing you could do in Putney, Wimbledon or Mortlake. Not without the Williams family getting to know, and talking about you in Welsh.

He sees three elderly Lowlanders struggling with their bundles and moves to help them. The packages are soft and bulky, samples of woollen cloth. A port officer gives them trouble about their documents, shouting into their faces. He lounges behind the clerk, pretending to be a Lowland oaf, and tells the merchants by holding up his fingers what he thinks a fair bribe. ‘Please,’ says one of them, in effortful English to the clerk, ‘will you take care of these English coins for me? I find them surplus.’ Suddenly the clerk is all smiles. The Lowlanders are all smiles; they would have paid much more. When they board they say, ‘The boy is with us.’

As they wait to cast off, they ask him his age. He says eighteen, but they laugh and say, child, you are never. He offers them fifteen, and they confer and decide that fifteen will do; they think he's younger, but they don't want to shame him. They ask what's happened to his face. There are several things he could say but he selects the truth. He doesn't want them to think he's some failed robber. They discuss it among themselves, and the one who can translate turns to him: ‘We are saying, the English are cruel to their children. And cold-hearted. The child must stand if his father comes in the room. Always the child should say very correctly, “my father, sir”, and “madam my mother”.’

He is surprised. Are there people in the world who are not cruel to their children? For the first time, the weight in his chest shifts a little; he thinks, there could be other places, better. He talks; he tells them about Bella, and they look sorry, and they don't say anything stupid like, you can get another dog. He tells them about the Pegasus, and about his father's brewhouse and how Walter gets fined for bad beer at least twice a year. He tells them about how he gets fines for stealing wood, cutting down other people's trees, and about the too-many sheep he runs on the common. They are interested in that; they show the woollen samples and discuss among themselves the weight and the weave, turning to him from time to time to include and instruct him. They don't think much of English finished cloth generally, though these samples can make them change their mind … He loses the thread of the conversation when they try to tell him their reasons for going to Calais, and different people they know there.

He tells them about his father's blacksmith business, and the English-speaker says, interested, can you make a horseshoe? He mimes to them what it's like, hot metal and a bad-tempered father in a small space. They laugh; they like to see him telling a story. Good talker, one of them says. Before they dock, the most silent of them will stand up and make an oddly formal speech, at which one will nod, and which the other will translate. ‘We are three brothers. This is our street. If ever you visit our town, there is a bed and hearth and food for you.’

Goodbye, he will say to them. Goodbye and good luck with your lives. Hwyl, cloth men. Golfalwch eich busness. He is not stopping till he gets to a war.

The weather is cold but the sea is flat. Kat has given him a holy medal to wear. He has slung it around his neck with a cord. It makes a chill against the skin of his throat. He unloops it. He touches it with his lips, for luck. He drops it; it whispers into the water. He will remember his first sight of the open sea: a grey wrinkled vastness, like the residue of a dream.

II Paternity 1527 (#ulink_7f3cbeea-9751-5edb-91f6-7301cd87379d)

So: Stephen Gardiner. Going out, as he's coming in. It's wet, and for a night in April, unseasonably warm, but Gardiner wears furs, which look like oily and dense black feathers; he stands now, ruffling them, gathering his clothes about his tall straight person like black angel's wings.

‘Late,’ Master Stephen says unpleasantly.

He is bland. ‘Me, or your good self?’

‘You.’ He waits.

‘Drunks on the river. The boatmen say it's the eve of one of their patron saints.’

‘Did you offer a prayer to her?’

‘I'll pray to anyone, Stephen, till I'm on dry land.’

‘I'm surprised you didn't take an oar yourself. You must have done some river work, when you were a boy.’

Stephen sings always on one note. Your reprobate father. Your low birth. Stephen is supposedly some sort of semi-royal by-blow: brought up for payment, discreetly, as their own, by discreet people in a small town. They are wool-trade people, whom Master Stephen resents and wishes to forget; and since he himself knows everybody in the wool trade, he knows too much about his past for Stephen's comfort. The poor orphan boy!

Master Stephen resents everything about his own situation. He resents that he's the king's unacknowledged cousin. He resents that he was put into the church, though the church has done well by him. He resents the fact that someone else has late-night talks with the cardinal, to whom he is confidential secretary. He resents the fact that he's one of those tall men who are hollow-chested, not much weight behind him; he resents his knowledge that if they met on a dark night, Master Thos. Cromwell would be the one who walked away dusting off his hands and smiling.

‘God bless you,’ Gardiner says, passing into the night unseasonably warm.

Cromwell says, ‘Thanks.’

The cardinal, writing, says without looking up, ‘Thomas. Still raining? I expected you earlier.’

Boatman. River. Saint. He's been travelling since early morning and in the saddle for the best part of two weeks on the cardinal's business, and has now come down by stages – and not easy stages – from Yorkshire. He's been to his clerks at Gray's Inn and borrowed a change of linen. He's been east to the city, to hear what ships have come in and to check the whereabouts of an off-the-books consignment he is expecting. But he hasn't eaten, and hasn't been home yet.

The cardinal rises. He opens a door, speaks to his hovering servants. ‘Cherries! What, no cherries? April, you say? Only April? We shall have sore work to placate my guest, then.’ He sighs. ‘Bring what you have. But it will never do, you know. Why am I so ill-served?’

Then the whole room is in motion: food, wine, fire built up. A man takes his wet outer garments with a solicitous murmur. All the cardinal's household servants are like this: comfortable, soft-footed, and kept permanently apologetic and teased. And all the cardinal's visitors are treated in the same way. If you had interrupted him every night for ten years, and sat sulking and scowling at him on each occasion, you would still be his honoured guest.

The servants efface themselves, melting away towards the door. ‘What else would you like?’ the cardinal says.

‘The sun to come out?’

‘So late? You tax my powers.’

‘Dawn would do.’

The cardinal inclines his head to the servants. ‘I shall see to this request myself,’ he says gravely; and gravely they murmur, and withdraw.

The cardinal joins his hands. He makes a great, deep, smiling sigh, like a leopard settling in a warm spot. He regards his man of business; his man of business regards him. The cardinal, at fifty-five, is still as handsome as he was in his prime. Tonight he is dressed not in his everyday scarlet, but in blackish purple and fine white lace: like a humble bishop. His height impresses; his belly, which should in justice belong to a more sedentary man, is merely another princely aspect of his being, and on it, confidingly, he often rests a large, white, beringed hand. A large head – surely designed by God to support the papal tiara – is carried superbly on broad shoulders: shoulders upon which rest (though not at this moment) the great chain of Lord Chancellor of England. The head inclines; the cardinal says, in those honeyed tones, famous from here to Vienna, ‘So now, tell me how was Yorkshire.’

‘Filthy.’ He sits down. ‘Weather. People. Manners. Morals.’

‘Well, I suppose this is the place to complain. Though I am already speaking to God about the weather.’

‘Oh, and the food. Five miles inland, and no fresh fish.’

‘And scant hope of a lemon, I suppose. What do they eat?’

‘Londoners, when they can get them. You have never seen such heathens. They're so high, low foreheads. Live in caves, yet they pass for gentry in those parts.’ He ought to go and look for himself, the cardinal; he is Archbishop of York, but has never visited his see. ‘And as for Your Grace's business –’

‘I am listening,’ the cardinal says. ‘Indeed, I go further. I am captivated.’

As he listens, the cardinal's face creases into its affable, perpetually attentive folds. From time to time he notes down a figure that he is given. He sips from a glass of his very good wine and at length he says, ‘Thomas … what have you done, monstrous servant? An abbess is with child? Two, three abbesses? Or, let me see … Have you set fire to Whitby, on a whim?’

In the case of his man Cromwell, the cardinal has two jokes, which sometimes unite to form one. The first is that he walks in demanding cherries in April and lettuce in December. The other is that he goes about the countryside committing outrages, and charging them to the cardinal's accounts. And the cardinal has other jokes, from time to time: as he requires them.

It is about ten o'clock. The flames of the wax candles bow civilly to the cardinal, and stand straight again. The rain – it has been raining since last September – splashes against the glass window. ‘In Yorkshire,’ he says, ‘your project is disliked.’

The cardinal's project: having obtained the Pope's permission, he means to amalgamate some thirty small, ill-run monastic foundations with larger ones, and to divert the income of these foundations – decayed, but often very ancient – into revenue for the two colleges he is founding: Cardinal College, at Oxford, and a college in his home town of Ipswich, where he is well remembered as the scholar son of a prosperous and pious master butcher, a guild-man, a man who also kept a large and well-regulated inn, of the type used by the best travellers. The difficulty is … No, in fact, there are several difficulties. The cardinal, a Bachelor of Arts at fifteen, a Bachelor of Theology by his mid-twenties, is learned in the law but does not like its delays; he cannot quite accept that real property cannot be changed into money, with the same speed and ease with which he changes a wafer into the body of Christ. When he once, as a test, explained to the cardinal just a minor point of the land law concerning – well, never mind, it was a minor point – he saw the cardinal break into a sweat and say, Thomas, what can I give you, to persuade you never to mention this to me again? Find a way, just do it, he would say when obstacles were raised; and when he heard of some small person obstructing his grand design, he would say, Thomas, give them some money to make them go away.

He has the leisure to think about this, because the cardinal is staring down at his desk, at the letter he has half-written. He looks up. ‘Tom …’ And then, ‘No, never mind. Tell me why you are scowling in that way.’

‘The people up there say they are going to kill me.’

‘Really?’ the cardinal says. His face says, I am astonished and disappointed. ‘And will they kill you? Or what do you think?’

Behind the cardinal is a tapestry, hanging the length of the wall. King Solomon, his hands stretched into darkness, is greeting the Queen of Sheba.

‘I think, if you're going to kill a man, do it. Don't write him a letter about it. Don't bluster and threaten and put him on his guard.’

‘If you ever plan to be off your guard, let me know. It is something I should like to see. Do you know who … But I suppose they don't sign their letters. I shall not give up my project. I have personally and carefully selected these institutions, and His Holiness has approved them under seal. Those who object misunderstand my intention. No one is proposing to put old monks out on the roads.’

This is true. There can be relocation; there can be pensions, compensation. It can be negotiated, with goodwill on both sides. Bow to the inevitable, he urges. Deference to the lord cardinal. Regard his watchful and fatherly care; believe his keen eye is fixed on the ultimate good of the church. These are the phrases with which to negotiate. Poverty, chastity and obedience: these are what you stress when you tell some senile prior what to do. ‘They don't misunderstand,’ he says. ‘They just want the proceeds themselves.’

‘You will have to take an armed guard when next you go north.’

The cardinal, who thinks upon a Christian's last end, has had his tomb designed already, by a sculptor from Florence. His corpse will lie beneath the outspread wings of angels, in a sarcophagus of porphyry. The veined stone will be his monument, when his own veins are drained by the embalmer; when his limbs are set like marble, an inscription of his virtues will be picked out in gold. But the colleges are to be his breathing monument, working and living long after he is gone: poor boys, poor scholars, carrying into the world the cardinal's wit, his sense of wonder and of beauty, his instinct for decorum and pleasure, his finesse. No wonder he shakes his head. You don't generally have to give an armed guard to a lawyer. The cardinal hates any show of force. He thinks it unsubtle. Sometimes one of his people – Stephen Gardiner, let's say – will come to him denouncing some nest of heretics in the city. He will say earnestly, poor benighted souls. You pray for them, Stephen, and I'll pray for them, and we'll see if between us we can't bring them to a better state of mind. And tell them, mend their manners, or Thomas More will get hold of them and shut them in his cellar. And all we will hear is the sound of screaming.

‘Now, Thomas.’ He looks up. ‘Do you have any Spanish?’

‘A little. Military, you know. Rough.’

‘You took service in the Spanish armies, I thought.’

‘French.’

‘Ah. Indeed. And no fraternising?’

‘Not past a point. I can insult people in Castilian.’

‘I shall bear that in mind,’ the cardinal says. ‘Your time may come. For now … I was thinking that it would be good to have more friends in the queen's household.’

Spies, he means. To see how she will take the news. To see what Queen Catalina will say, in private and unleashed, when she has slipped the noose of the diplomatic Latin in which it will be broken to her that the king – after they have spent some twenty years together – would like to marry another lady. Any lady. Any well-connected princess whom he thinks might give him a son.

The cardinal's chin rests on his hand; with finger and thumb, he rubs his eyes. ‘The king called me this morning,’ he says, ‘exceptionally early.’

‘What did he want?’

‘Pity. And at such an hour. I heard a dawn Mass with him, and he talked all through it. I love the king. God knows how I love him. But sometimes my faculty of commiseration is strained.’ He raises his glass, looks over the rim. ‘Picture to yourself, Tom. Imagine this. You are a man of some thirty-five years of age. You are in good health and of a hearty appetite, you have your bowels opened every day, your joints are supple, your bones support you, and in addition you are King of England. But.’ He shakes his head. ‘But! If only he wanted something simple. The Philosopher's Stone. The elixir of youth. One of those chests that occur in stories, full of gold pieces.’

‘And when you take some out, it just fills up again?’

‘Exactly. Now the chest of gold I have hopes of, and the elixir, all the rest. But where shall I begin looking for a son to rule his country after him?’

Behind the cardinal, moving a little in the draught, King Solomon bows, his face obscured. The Queen of Sheba – smiling, light-footed – reminds him of the young widow he lodged with when he lived in Antwerp. Since they had shared a bed, should he have married her? In honour, yes. But if he had married Anselma he couldn't have married Liz; and his children would be different children from the ones he has now.

‘If you cannot find him a son,’ he says, ‘you must find him a piece of scripture. To ease his mind.’

The cardinal appears to be looking for it, on his desk. ‘Well, Deuteronomy. Which positively recommends that a man should marry his deceased brother's wife. As he did.’ The cardinal sighs. ‘But he doesn't like Deuteronomy.’

Useless to say, why not? Useless to suggest that, if Deuteronomy orders you to marry your brother's relict, and Leviticus says don't, or you will not breed, you should try to live with the contradiction, and accept that the question of which takes priority was thrashed out in Rome, for a fat fee, by leading prelates, twenty years ago when the dispensations were issued, and delivered under papal seal.

‘I don't see why he takes Leviticus to heart. He has a daughter living.’

‘But I think it is generally understood, in the Scriptures, that “children” means “sons”.’

The cardinal justifies the text, referring to the Hebrew; his voice is mild, lulling. He loves to instruct, where there is the will to be instructed. They have known each other some years now, and though the cardinal is very grand, formality has faded between them. ‘I have a son,’ he says. ‘You know that, of course. God forgive me. A weakness of the flesh.’

The cardinal's son – Thomas Winter, they call him – seems inclined to scholarship and a quiet life; though his father may have other ideas. The cardinal has a daughter too, a young girl whom no one has seen. Rather pointedly, he has called her Dorothea, the gift of God; she is already placed in a convent, where she will pray for her parents.

‘And you have a son,’ the cardinal says. ‘Or should I say, you have one son you give your name to. But I suspect there are some you don't know, running around on the banks of the Thames?’

‘I hope not. I wasn't fifteen when I ran away.’

It amuses Wolsey, that he doesn't know his age. The cardinal peers down through the layers of society, to a stratum well below his own, as the butcher's beef-fed son; to a place where his servant is born, on a day unknown, in deep obscurity. His father was no doubt drunk at his birth; his mother, understandably, was preoccupied. Kat has assigned him a date; he is grateful for it.

‘Well, fifteen …’ the cardinal says. ‘But at fifteen I suppose you could do it? I know I could. Now I have a son, your boatman on the river has a son, your beggar on the street has a son, your would-be murderers in Yorkshire no doubt have sons who will be sworn to pursue you in the next generation, and you yourself, as we have agreed, have spawned a whole tribe of riverine brawlers – but the king, alone, has no son. Whose fault is that?’

‘God's?’

‘Nearer than God?’

‘The queen?’

‘More responsible for everything than the queen?’

He can't help a broad smile. ‘Yourself, Your Grace.’

‘Myself, My Grace. What am I going to do about it? I tell you what I might do. I might send Master Stephen to Rome to sound out the Curia. But then I need him here …’

Wolsey looks at his expression, and laughs. Squabbling underlings! He knows quite well that, dissatisfied with their original parentage, they are fighting to be his favourite son. ‘Whatever you think of Master Stephen, he is well grounded in canon law, and a very persuasive fellow, except when he tries to persuade you. I will tell you –’ He breaks off; he leans forward, he puts his great lion's head in his hands, the head that would indeed have worn the papal tiara, if at the last election the right money had been paid out to the right people. ‘I have begged him,’ the cardinal says. ‘Thomas, I sank to my knees and from that humble posture I tried to dissuade him. Majesty, I said, be guided by me. Nothing will ensue, if you wish to be rid of your wife, but a great deal of trouble and expense.’

‘And he said …?’

‘He held up a finger. In warning. “Never,” he said, “call that dear lady my wife, until you can show me why she is, and how it can be so. Till then, call her my sister, my dear sister. Since she was quite certainly my brother's wife, before going through a form of marriage with me.”’

You will never draw from Wolsey a word that is disloyal to the king. ‘What it is,’ he says, ‘it's …’ he hesitates over the word, ‘it's, in my opinion … preposterous. Though my opinion, of course, does not go out of this room. Oh, don't doubt it, there were those at the time who raised their eyebrows over the dispensation. And year by year there were persons who would murmur in the king's ear; he didn't listen, though now I must believe that he heard. But you know the king was the most uxorious of men. Any doubts were quashed.’ He places a hand, softly and firmly, down on his desk. ‘They were quashed and quashed.’

But there is no doubt of what Henry wants now. An annulment. A declaration that his marriage never existed. ‘For eighteen years,’ the cardinal says, ‘he has been under a mistake. He has told his confessor that he has eighteen years' worth of sin to expiate.’

He waits, for some gratifying small reaction. His servant simply looks back at him: taking it for granted that the seal of the confessional is broken at the cardinal's convenience.

‘So if you send Master Stephen to Rome,’ he says, ‘it will give the king's whim, if I may –’

The cardinal nods: you may so term it.

‘– an international airing?’

‘Master Stephen may go discreetly. As it were, for a private papal blessing.’

‘You don't understand Rome.’

Wolsey can't contradict him. He has never felt the chill at the nape of the neck that makes you look over your shoulder when, passing from the Tiber's golden light, you move into some great bloc of shadow. By some fallen column, by some chaste ruin, the thieves of integrity wait, some bishop's whore, some nephew-of-a-nephew, some monied seducer with furred breath; he feels, sometimes, fortunate to have escaped that city with his soul intact.

‘Put simply,’ he says, ‘the Pope's spies will guess what Stephen's about while he is still packing his vestments, and the cardinals and the secretaries will have time to fix their prices. If you must send him, give him a great deal of ready money. Those cardinals don't take promises; what they really like is a bag of gold to placate their bankers, because they're mostly run out of credit.’ He shrugs. ‘I know this.’

‘I should send you,’ the cardinal says, jolly. ‘You could offer Pope Clement a loan.’

Why not? He knows the money markets; it could probably be arranged. If he were Clement, he would borrow heavily this year to hire in troops to ring his territories. It's probably too late; for the summer season's fighting, you need to be recruiting by Candlemas. He says, ‘Will you not start the king's suit within your own jurisdiction? Make him take the first steps, then he will see if he really wants what he says he wants.’

‘That is my intention. What I mean to do is to convene a small court here in London. We will approach him in a shocked fashion: King Harry, you appear to have lived all these years in an unlawful manner, with a woman not your wife. He hates – saving His Majesty – to appear in the wrong: which is where we must put him, very firmly. Possibly he will forget that the original scruples were his. Possibly he will shout at us, and hasten in a fit of indignation back to the queen. If not, then I must have the dispensation revoked, here or in Rome, and if I succeed in parting him from Katherine I shall marry him, smartly, to a French princess.’

No need to ask if the cardinal has any particular princess in mind. He has not one but two or three. He never lives in a single reality, but in a shifting, shadow-mesh of diplomatic possibilities. While he is doing his best to keep the king married to Queen Katherine and her Spanish-Imperial family, by begging Henry to forget his scruples, he will also plan for an alternative world, in which the king's scruples must be heeded, and the marriage to Katherine is void. Once that nullity is recognised – and the last eighteen years of sin and suffering wiped from the page – he will readjust the balance of Europe, allying England with France, forming a power bloc to oppose the young Emperor Charles, Katherine's nephew. And all outcomes are likely, all outcomes can be managed, even massaged into desirability: prayer and pressure, pressure and prayer, everything that comes to pass will pass by God's design, a design re-envisaged and redrawn, with helpful emendations, by the cardinal. He used to say, ‘The king will do such-and-such.’ Then he began to say, ‘We will do such-and-such.’ Now he says, ‘This is what I will do.’

‘But what will happen to the queen?’ he asks. ‘If he casts her off, where will she go?’

‘Convents can be comfortable.’

‘Perhaps she will go home to Spain.’

‘No, I think not. It is another country now. It is – what? – twenty-seven years since she landed in England.’ The cardinal sighs. ‘I remember her, at her coming-in. Her ships, as you know, had been delayed by the weather, and she had been day upon day tossed in the Channel. The old king rode down the country, determined to meet her. She was then at Dogmersfield, at the Bishop of Bath's palace, and making slow progress towards London; it was November and, yes, it was raining. At his arriving, her household stood upon their Spanish manners: the princess must remained veiled, until her husband sees her on her wedding day. But you know the old king!’

He did not, of course; he was born on or about the date the old king, a renegade and a refugee all his life, fought his way to an unlikely throne. Wolsey talks as if he himself had witnessed everything, eye-witnessed it, and in a sense he has, for the recent past arranges itself only in the patterns acknowledged by his superior mind, and agreeable to his eye. He smiles. ‘The old king, in his later years, the least thing could arouse his suspicion. He made some show of reining back to confer with his escort, and then he leapt – he was still a lean man – from the saddle, and told the Spanish to their faces, he would see her or else. My land and my laws, he said; we'll have no veils here. Why may I not see her, have I been cheated, is she deformed, is it that you are proposing to marry my son Arthur to a monster?’

Thomas thinks, he was being unnecessarily Welsh.

‘Meanwhile her women had put the little creature into bed; or said they had, for they thought that in bed she would be safe against him. Not a bit. King Henry strode through the rooms, looking as if he had in mind to tear back the bedclothes. The women bundled her into some decency. He burst into the chamber. At the sight of her, he forgot his Latin. He stammered and backed out like a tongue-tied boy.’ The cardinal chuckled. ‘And then when she first danced at court – our poor prince Arthur sat smiling on the dais, but the little girl could hardly sit still in her chair – no one knew the Spanish dances, so she took to the floor with one of her ladies. I will never forget that turn of her head, that moment when her beautiful red hair slid over one shoulder … There was no man who saw it who didn't imagine – though the dance was in fact very sedate … Ah dear. She was sixteen.’

The cardinal looks into space and Thomas says, ‘God forgive you?’

‘God forgive us all. The old king was constantly taking his lust to confession. Prince Arthur died, then soon after the queen died, and when the old king found himself a widower he thought he might marry Katherine himself. But then …’ He lifts his princely shoulders. ‘They couldn't agree over the dowry, you know. The old fox, Ferdinand, her father. He would fox you out of any payment due. But our present Majesty was a boy of ten when he danced at his brother's wedding, and, in my belief, it was there and then that he set his heart on the bride.’

They sit and think for a bit. It's sad, they both know it's sad. The old king freezing her out, keeping her in the kingdom and keeping her poor, unwilling to miss the part of the dowry he said was still owing, and equally unwilling to pay her widow's portion and let her go. But then it's interesting too, the extensive diplomatic contacts the little girl picked up during those years, the expertise in playing off one interest against another. When Henry married her he was eighteen, guileless. His father was no sooner dead than he claimed Katherine for his own. She was older than he was, and years of anxiety had sobered her and taken something from her looks. But the real woman was less vivid than the vision in his mind; he was greedy for what his older brother had owned. He felt again the little tremor of her hand, as she had rested it on his arm when he was a boy of ten. It was as if she had trusted him, as if – he told his intimates – she had recognised that she was never meant to be Arthur's wife, except in name; her body was reserved for him, the second son, upon whom she turned her beautiful blue-grey eyes, her compliant smile. She always loved me, the king would say. Seven years or so of diplomacy, if you can call it that, kept me from her side. But now I need fear no one. Rome has dispensed. The papers are in order. The alliances are set in place. I have married a virgin, since my poor brother did not touch her; I have married an alliance, her Spanish relatives; but, above all, I have married for love.

And now? Gone. Or as good as gone: half a lifetime waiting to be expunged, eased from the record.

‘Ah, well,’ the cardinal says. ‘What will be the outcome? The king expects his own way, but she, she will be hard to move.’

There is another story about Katherine, a different story. Henry went to France to have a little war; he left Katherine as regent. Down came the Scots; they were well beaten, and at Flodden the head of their king cut off. It was Katherine, that pink-and-white angel, who proposed to send the head in a bag by the first crossing, to cheer up her husband in his camp. They dissuaded her; told her it was, as a gesture, un-English. She sent, instead, a letter. And with it, the surcoat in which the Scottish king had died, which was stiffened, black and crackling with his pumped-out blood.

The fire dies, an ashy log subsiding; the cardinal, wrapped in his dreams, rises from his chair and personally kicks it. He stands looking down, twisting the rings on his fingers, lost in thought. He shakes himself and says, ‘Long day. Go home. Don't dream of Yorkshiremen.’

Thomas Cromwell is now a little over forty years old. He is a man of strong build, not tall. Various expressions are available to his face, and one is readable: an expression of stifled amusement. His hair is dark, heavy and waving, and his small eyes, which are of very strong sight, light up in conversation: so the Spanish ambassador will tell us, quite soon. It is said he knows by heart the entire New Testament in Latin, and so as a servant of the cardinal is apt – ready with a text if abbots flounder. His speech is low and rapid, his manner assured; he is at home in courtroom or waterfront, bishop's palace or inn yard. He can draft a contract, train a falcon, draw a map, stop a street fight, furnish a house and fix a jury. He will quote you a nice point in the old authors, from Plato to Plautus and back again. He knows new poetry, and can say it in Italian. He works all hours, first up and last to bed. He makes money and he spends it. He will take a bet on anything.

He rises to leave, says, ‘If you did have a word with God and the sun came out, then the king could ride out with his gentlemen, and if he were not so fretted and confined then his spirits would rise, and he might not be thinking about Leviticus, and your life would be easier.’

‘You only partly understand him. He enjoys theology, almost as much as he enjoys riding out.’

He is at the door. Wolsey says, ‘By the way, the talk at court … His Grace the Duke of Norfolk is complaining that I have raised an evil spirit, and directed it to follow him about. If anyone mentions it to you … just deny it.’

He stands in the doorway, smiling slowly. The cardinal smiles too, as if to say, I have saved the good wine till last. Don't I know how to make you happy? Then the cardinal drops his head over his papers. He is a man who, in England's service, scarcely needs to sleep; four hours will refresh him, and he will be up when Westminster's bells have rung in another wet, smoky, lightless April day. ‘Good night,’ he says. ‘God bless you, Tom.’

Outside his people are waiting with lights to take him home. He has a house in Stepney but tonight he is going to his town house. A hand on his arm: Rafe Sadler, a slight young man with pale eyes. ‘How was Yorkshire?’

Rafe's smile flickers, the wind pulls the torch flame into a rainy blur.

‘I haven't to speak of it; the cardinal fears it will give us bad dreams.’

Rafe frowns. In all his twenty-one years he has never had bad dreams; sleeping securely under the Cromwell roof since he was seven, first at Fenchurch Street and now at the Austin Friars, he has grown up with a tidy mind, and his night-time worries are all rational ones: thieves, loose dogs, sudden holes in the road.

‘The Duke of Norfolk …’ he says, then, ‘no, never mind. Who's been asking for me while I've been away?’

The damp streets are deserted; the mist is creeping from the river. The stars are stifled in damp and cloud. Over the city lies the sweet, rotting odour of yesterday's unrecollected sins. Norfolk kneels, teeth chattering, beside his bed; the cardinal's late-night pen scratches, scratches, like a rat beneath his mattress. While Rafe, by his side, gives him a digest of the office news, he formulates his denial, for whom it may concern: ‘His Grace the cardinal wholly rejects any imputation that he has sent an evil spirit to wait upon the Duke of Norfolk. He deprecates the suggestion in the strongest possible terms. No headless calf, no fallen angel in the shape of loll-tongued dog, no crawling pre-used winding sheet, no Lazarus nor animated cadaver has been sent by His Grace to pursue His Grace: nor is any such pursuit pending.’

Someone is screaming, down by the quays. The boatmen are singing. There is a faint, faraway splashing; perhaps they are drowning someone. ‘My lord cardinal makes this statement without prejudice to his right to harass and distress my lord of Norfolk by means of any fantasma which he may in his wisdom elect: at any future date, and without notice given: subject only to the lord cardinal's views in the matter.’

This weather makes old scars ache. But he walks into his house as if it were midday: smiling, and imagining the trembling duke. It is one o'clock. Norfolk, in his mind, is still kneeling. A black-faced imp with a trident is pricking his calloused heels.

III At Austin Friars 1527 (#ulink_5abf15dc-82a1-5eca-8e63-2b61709e48a7)

Lizzie is still up. When she hears the servants let him in, she comes out with his little dog under her arm, fighting and squealing.

‘Forget where you lived?’

He sighs.

‘How was Yorkshire?’

He shrugs.

‘The cardinal?’

He nods.

‘Eaten?’

‘Yes.’

‘Tired?’

‘Not really.’

‘Drink?’

‘Yes.’

‘Rhenish?’

‘Why not.’

The panelling has been painted. He walks into the subdued green and golden glow. ‘Gregory –’

‘Letter?’

‘Of sorts.’

She gives him the letter and the dog, while she fetches the wine. She sits down, taking a cup herself.

‘He greets us. As if there were only one of us. Bad Latin.’

‘Ah, well,’ she says.

‘So, listen. He hopes you are well. Hopes I am well. Hopes his lovely sisters Anne and little Grace are well. He himself is well. And now no more for lack of time, your dutiful son, Gregory Cromwell.’

‘Dutiful?’ she says. ‘Just that?’

‘It's what they teach them.’

The dog Bella nibbles his fingertips, her round innocent eyes shining at him like alien moons. Liz looks well, if worn by her long day; wax tapers stand tall and straight behind her. She is wearing the string of pearls and garnets that he gave her at New Year.

‘You're sweeter to look at than the cardinal,’ he says.

‘That's the smallest compliment a woman ever received.’

‘And I've been working on it all the way from Yorkshire.’ He shakes his head. ‘Ah well!’ He holds Bella up in the air; she kicks her legs in glee. ‘How's business?’

Liz does a bit of silk-work. Tags for the seals on documents; fine net cauls for ladies at court. She has two girl apprentices in the house, and an eye on fashion; but she complains, as always, about the middlemen, and the price of thread. ‘We should go to Genoa,’ he says. ‘I'll teach you to look the suppliers in the eye.’

‘I'd like that. But you'll never get away from the cardinal.’

‘He tried to persuade me tonight that I should get to know people in the queen's household. The Spanish-speakers.’

‘Oh?’

‘I told him my Spanish wasn't so good.’

‘Not good?’ She laughs. ‘You weasel.’

‘He doesn't have to know everything I know.’

‘I've been visiting in Cheapside,’ she says. She names one of her old friends, a master jeweller's wife. ‘Would you like the news? A big emerald was ordered and a setting commissioned, for a ring, a woman's ring.’ She shows him the emerald, big as her thumbnail.

‘Which arrived, after a few anxious weeks, and they were cutting it in Antwerp.’ Her fingers flick outwards. ‘Shattered!’

‘So who bears the loss?’

‘The cutter says he was swindled and it was a hidden flaw in the base. The importer says, if it was so hidden, how could I be expected to know? The cutter says, so collect damages from your supplier …’

‘They'll be at law for years. Can they get another?’

‘They're trying. It must be the king, so we think. Nobody else in London would be in the market for a stone of that size. So who's it for? It isn't for the queen.’

The tiny Bella now lies back along his arm, her eyes blinking, her tail gently stirring. He thinks, I shall be curious to see if and when an emerald ring appears. The cardinal will tell me. The cardinal says, it's all very well, this business of holding the king off and angling after presents, but he will have her in his bed this summer, for sure, and by the autumn he'll be tired of her, and pension her off; if he doesn't, I will. If Wolsey's going to import a fertile French princess, he doesn't want her first weeks spoiled by scenes of spite with superseded concubines. The king, Wolsey thinks, ought to be more ruthless about his women.

Liz waits for a moment, till she knows she isn't going to get a hint. ‘Now, about Gregory,’ she says. ‘Summer coming. Here, or away?’

Gregory is coming up thirteen. He's at Cambridge, with his tutor. He's sent his nephews, his sister Bet's sons, to school with him; it's something he is glad to do for the family. The summer is for their recreation; what would they do in the city? Gregory has little interest in his books so far, though he likes to be told stories, dragon stories, stories of green people who live in the woods; you can drag him squealing through a passage of Latin if you persuade him that over the page there's a sea serpent or a ghost. He likes to be in the woods and fields and he likes to hunt. He has plenty of growing to do, and we hope he will grow tall.

The king's maternal grandfather, as all old men will tell you, stood six foot four. (His father, however, was more the size of Morgan Williams.) The king stands six foot two, and the cardinal can look him in the eye. Henry likes to have about him men like his brother-in-law Charles Brandon, of a similar impressive height and breadth of padded shoulder. Height is not the fashion in the back alleys; and, obviously, not in Yorkshire.

He smiles. What he says about Gregory is, at least he isn't like I was, when I was his age; and when people say, what were you like? he says, oh, I used to stick knives in people. Gregory would never do that; so he doesn't mind – or minds less than people think – if he doesn't really get to grips with declensions and conjugations. When people tell him what Gregory has failed to do, he says, ‘He's busy growing.’ He understands his need to sleep; he never got much sleep himself, with Walter stamping around, and after he ran away he was always on the ship or on the road, and then he found himself in an army. The thing people don't understand about an army is its great, unpunctuated wastes of inaction: you have to scavenge for food, you are camped out somewhere with a rising water level because your mad capitaine says so, you are shifted abruptly in the middle of the night into some indefensible position, so you never really sleep, your equipment is defective, the gunners keep causing small unwanted explosions, the crossbow-men are either drunk or praying, the arrows are ordered up but not here yet, and your whole mind is occupied by a seething anxiety that things are going to go badly because il principe, or whatever little worshipfulness is in charge today, is not very good at the basic business of thinking. It didn't take him many winters to get out of fighting and into supply. In Italy, you could always fight in the summer, if you felt like it. If you wanted to go out.

‘Asleep?’ Liz says.

‘No. But dreaming.’

‘The Castile soap came. And your book from Germany. It was packaged as something else. I almost sent the boy away.’

In Yorkshire, which smelled of unwashed men, wearing sheepskins and sweating with anger, he had dreams about the Castile soap.

Later she says, ‘So who is the lady?’

His hand, resting on her familiar but lovely left breast, removes itself in bewilderment. ‘What?’ Does she think he has taken up with some woman in Yorkshire? He falls on to his back and wonders how to persuade her this is not so; if necessary he'll take her there, and then she'll see.

‘The emerald lady?’ she says. ‘I only ask because people say the king is wanting to do something very strange, and I can't really believe it. But that is the word in the city.’

Really? Rumour has advanced, in the fortnight while he has been north among the slope-heads.

‘If he tries this,’ she says, ‘then half the people in the world will be against it.’

He had only thought, and Wolsey had only thought, that the Emperor and Spain would be against it. Only the Emperor. He smiles in the dark, hands behind his head. He doesn't say, which people, but waits for Liz to tell him. ‘All women,’ she says. ‘All women everywhere in England. All women who have a daughter but no son. All women who have lost a child. All women who have lost any hope of having a child. All women who are forty.’

She puts her head on his shoulder. Too tired to speak, they lie side by side, in sheets of fine linen, under a quilt of yellow turkey satin. Their bodies breathe out the faint borrowed scent of sun and herbs. In Castilian, he remembers, he can insult people.

‘Are you asleep now?’

‘No. Thinking.’

‘Thomas,’ she says, sounding shocked, ‘it's three o'clock.’

And then it is six. He dreams that all the women of England are in bed, jostling and pushing him out of it. So he gets up, to read his German book, before Liz can do anything about it.

It's not that she says anything; or only, when provoked, she says, ‘My prayer book is good reading for me.’ And indeed she does read her prayer book, taking it in her hand absently in the middle of the day – but only half stopping what she's doing – interspersing her murmured litany with household instructions; it was a wedding present, a book of hours, from her first husband, and he wrote her new married name in it, Elizabeth Williams. Sometimes, feeling jealous, he would like to write other things, contrarian sentiments: he knew Liz's first husband, but that doesn't mean he liked him. He has said, Liz, there's Tyndale's book, his New Testament, in the locked chest there, read it, here's the key; she says, you read it to me if you're so keen, and he says, it's in English, read it for yourself: that's the point, Lizzie. You read it, you'll be surprised what's not in it.

He'd thought this hint would draw her: seemingly not. He can't imagine himself reading to his household; he's not, like Thomas More, some sort of failed priest, a frustrated preacher. He never sees More – a star in another firmament, who acknowledges him with a grim nod – without wanting to ask him, what's wrong with you? Or what's wrong with me? Why does everything you know, and everything you've learned, confirm you in what you believed before? Whereas in my case, what I grew up with, and what I thought I believed, is chipped away a little and a little, a fragment then a piece and then a piece more. With every month that passes, the corners are knocked off the certainties of this world: and the next world too. Show me where it says, in the Bible, ‘Purgatory’. Show me where it says relics, monks, nuns. Show me where it says ‘Pope’.

He turns back to his German book. The king, with help from Thomas More, has written a book against Luther, for which the Pope has granted him the title of Defender of the Faith. It's not that he loves Brother Martin himself; he and the cardinal agree it would be better if Luther had never been born, or better if he had been born more subtle. Still, he keeps up with what's written, with what's smuggled through the Channel ports, and the little East Anglian inlets, the tidal creeks where a small boat with dubious cargo can be beached and pushed out again, by moonlight, to sea. He keeps the cardinal informed, so that when More and his clerical friends storm in, breathing hellfire about the newest heresy, the cardinal can make calming gestures, and say, ‘Gentlemen, I am already informed.’ Wolsey will burn books, but not men. He did so, only last October, at St Paul's Cross: a holocaust of the English language, and so much rag-rich paper consumed, and so much black printers' ink.

The Testament he keeps in the chest is the pirated edition from Antwerp, which is easier to get hold of than the proper German printing. He knows William Tyndale; before London got too hot for him, he lodged six months with Humphrey Monmouth, the master draper, in the city. He is a principled man, a hard man, and Thomas More calls him The Beast; he looks as if he has never laughed in his life, but then, what's there to laugh about, when you're driven from your native shore? His Testament is in octavo, nasty cheap paper: on the title page, where the printer's colophon and address should be, the words ‘PRINTED IN UTOPIA’. He hopes Thomas More has seen one of these. He is tempted to show him, just to see his face.

He closes the new book. It's time to get on with the day. He knows he has not time to put the text into Latin himself, so it can be discreetly circulated; he should ask somebody to do it for him, for love or money. It is surprising how much love there is, these days, between those who read German.

By seven, he is shaved, breakfasted and wrapped beautifully in fresh unborrowed linen and dark fine wool. Sometimes, at this hour, he misses Liz's father; that good old man, who would always be up early, ready to drop a flat hand on his head and say, enjoy your day, Thomas, on my behalf.