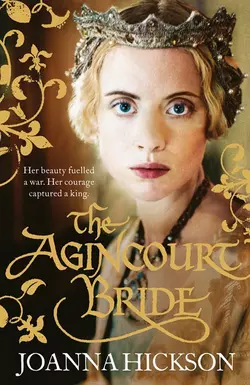

The Agincourt Bride

Joanna Hickson

Shortlisted for the Romantic Novelists’ Association Historical Fiction award, The Agincourt Bride tells the thrilling story of the French princess who became an English queen.When her own first child is tragically still-born, the young Mette is pressed into service as a wet-nurse at the court of the mad king, Charles VI of France. Her young charge is the princess, Catherine de Valois, caught up in the turbulence and chaos of life at court.Mette and the child forge a bond, one that transcends Mette’s lowly position. But as Catherine approaches womanhood, her unique position seals her fate as a pawn between two powerful dynasties. Her brother, The Dauphin and the dark and sinister, Duke of Burgundy will both use Catherine to further the cause of France.Catherine is powerless to stop them, but with the French defeat at the Battle of Agincourt, the tables turn and suddenly her currency has never been higher. But can Mette protect Catherine from forces at court who seek to harm her or will her loyalty to Catherine place her in even greater danger?

JOANNA HICKSON

The Agincourt Bride

Copyright (#ulink_76fb2770-c718-59fb-aaec-b7aa96b5aed8)

This novel is entirely a work of fiction.

The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Copyright © Joanna Hickson 2013

Joanna Hickson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007446971

Ebook Edition © JANUARY 2013 ISBN: 9780007446988

Version: 2017-10-18

Dedication (#ulink_dd4455e5-ec8a-5c4b-ade6-01baa1f744d3)

For Ian and Barley – the two who share my life, thank goodness.

The House of Valois (#ulink_903fe2ff-d59d-5193-934c-3a94d8c27049)

Epigraph (#ulink_b1ffb852-8e52-5b8d-9e5a-aa97daf96710)

“It is written in the stars that I and my heirs shall rule France and yours shall rule England.

Our nations shall never live in peace. You and Henry have done this.”

Charles, Dauphin of France

Table of Contents

Cover (#u80e19e63-6336-5ca8-a48f-78025a9faecb)

Title Page (#uc1024330-8c28-594f-9306-60763089b349)

Copyright (#u67598198-b52d-5943-ba1c-f5f8add56f0a)

Dedication (#u53118d36-5e9f-5206-9681-b0360ff8cf8d)

The House of Valois (#udf1b9c65-351c-573d-908d-5a8ff3e08cee)

Epigraph (#udf4a769e-0dfb-5c8d-997c-7a6a584df2bf)

Narrator’s Note (#u14d1f8fd-d090-507b-bb4b-f2929d0072ed)

Part One (#ued13bfe1-25cc-58e9-a309-0420dfad073e)

Chapter 1 (#u232b3258-fd0b-5b0a-a949-1f04a80fb92d)

Chapter 2 (#u7b2b1647-d01f-5105-9221-6f65a891c779)

Chapter 3 (#u490ac892-94cb-5c7d-850b-6c021570dd08)

Chapter 4 (#u76053581-94ab-5773-a6a9-d1bb0bceca9e)

Chapter 5 (#u28d142c4-6e08-557e-8e58-83155df35f0e)

Part Two (#ua0c8e135-99b5-532e-bbd5-6ed9328a9b6e)

Chapter 6 (#uf5f91961-e497-5652-bcb4-024b6eb8f306)

Chapter 7 (#u8bc58c18-9a88-5817-bb84-e87614b82854)

Chapter 8 (#u32d5f341-13ca-526f-8dc9-a6428e921ebe)

Chapter 9 (#uc2976291-ca32-513e-9804-f702bdcd426f)

Chapter 10 (#u036e219c-7368-5a5f-970f-b789cc34591b)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Extract from The Tudor Bride (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

NARRATOR’S NOTE (#ulink_d8aafa79-fca4-522a-a692-d97b9d7541f9)

January 1439

Respected reader,

Before we embark on this story together, I think I should explain that I am not a historian or a chronicler or indeed any kind of scholar. I did not even read Latin until my dear and present husband undertook to teach me on dark winter nights by the fire in our London house, when a more dutiful goodwife would have been doing her embroidery. Luckily my days of being dutiful are behind me. I am now fifty-two years of age and I have had quite enough of stitching and scrubbing and answering becks and calls. I have been a servant and I have been a courtier and now I am neither so I have become a scribe, for one good reason; to tell the story of a brave and beautiful princess who wanted the impossible – to be happy. Of course, here at the start of the tale, I am not going to tell you whether she succeeded but I can tell you that some momentous events, scurrilous intrigues and monstrously evil acts conspired to prevent it.

Two things encouraged me to write this story. The first was those Latin lessons, for they enabled me to read the second, which was a cache of letters found when I used a key entrusted to me for safekeeping by my beloved mistress, the aforementioned princess, to open a secret compartment in the gift she bequeathed to me on her untimely death. These were confidential letters, written at turbulent times in her life, and she was never able to send them to their intended recipients. But they filled gaps in my knowledge and shed light on her character and the reasons she chose the paths she followed.

Sadly, for the most part, she was powerless to shape the direction of her own life, however hard she tried. But there were one or two occasions when she, and I too by extraordinary circumstance, managed to steer the course of events in a direction favourable to us both, although this was never recorded in the chronicles of history.

I do not have much time for chroniclers anyway. They invariably have a hidden agenda, observing events from one side only, and even then you cannot trust them to get a story right. Some are no better than the ink-slingers who nail their pamphlets to St Paul’s Cross. One of them got my name wrong when he recorded the list of my mistress’ companions back in the days of Good King Harry. ‘Guillemot’ he called me, if you can believe it! Who but a short-sighted, misogynistic monk would saddle a woman with the same name as an ugly black auk-bird? But there it is, in indelible ink, and it will probably endure into history. I beg you, respected reader, do not fall into the trap of believing all you read in chronicles, for my name is not Guillemot. What it is you will discover in the story I am about to tell …

PART ONE (#ulink_e4bfb792-a581-582a-8e39-95ebfd177204)

Hôtel de St Pol, Paris

The Court of the Mad King

1401–5

1 (#ulink_480104ef-e953-5066-a725-fb2f0dc8a55c)

It was a magnificent birth.

A magnificent, gilded, cushioned-in-swansdown birth which was the talk of the town; for the life and style of Queen Isabeau were discussed and dissected in every Paris marketplace – her fabulous gowns, her glittering jewels, her grand entertainments and above all the fact that she rarely paid what she owed for any of them. The fountain gossips deplored her notorious self-indulgence and knew that, like the arrival of all her other babies, the birth of her tenth child would be a glittering, gem-studded occasion illuminated by blazing chandeliers and that they would effectively be funding it. Paris was a city of merchants and craftsmen who relied on the royals and nobles to spend their money on beautiful clothes and artefacts and when they did not pay their bills, people starved and ferment festered. Not that the queen spared a moment’s thought for any of that, probably.

For my own part, when I heard the details of her lying-in, I thought the whole process sounded horrible. It’s one thing to give birth on a gilded bed but at such a time who would want a bunch of bearded, fur-trimmed worthies peering down and making whispered comments on every gasp and groan? With the notable exception of the king, it seemed that half the court was present; the Grand Master of the Royal Household, the Chancellor of the Treasury and a posse of barons and bishops. All the queen’s ladies attended and, for some arcane reason, the Presidents of the Court of Justice, the Privy Council and the University. I do not know how the queen felt about it, but from the poor infant’s point of view it must have been like starting life on a busy stall in a crowded market place.

Being born in a feather bed was the last the poor babe knew of luxury though, or of a mother’s touch. I can vouch for that. In the fourteen years of her marriage to King Charles the Sixth of France, Queen Isabeau had already popped out four boys and five girls like seeds from a pod, which was about the level of her maternal interest in them. It was questionable whether she even knew how many of them still lived.

Once all the worthies had verified that the new arrival was genuinely fresh-sprung from the royal loins and noted that it was regrettably another girl, the poor little scrap was whisked away to the nursery to be trussed up in those tight linen bands the English call swaddling. So when I first clapped eyes on her she looked like an angry parcel, screaming fit to burst.

I did not take to her at first and who could blame me? It was hard being presented with all that squalling evidence of life, when only a few hours ago my own newborn babe had died before I was even able to hold him.

‘You must be brave, little one,’ my mother said, her voice hoarse with grief as she wrapped the tiny blue corpse of my firstborn son in her best linen napkin. ‘Save your tears for the living and your love for the good God.’

Kindly meant words that were impossible to heed, for my world had turned dark and formless and all I could do was weep, great hiccoughing sobs that threatened to snatch the breath from my body. In truth I wasn’t weeping for my dead son, I was weeping for myself, swamped with guilt and self-loathing and convinced that my existence was pointless if I could not produce a living child. In my grief, God forgive me, I had forgotten that it was He who gives life and He who takes it away. I only knew that my arms ached for my belly’s burden and desolation flowed from me like the Seine in spate. So too, in due course, did my milk – sad, useless gouts of it, oozing from my nipples and soaking my chemise, making the cloth cling to my pathetic swollen breasts. Ma brought linen strips and tried to bind them to make it stop but it hurt like devil’s fire and I pushed her away. And so it was that my whole life changed.

But I am getting ahead of myself.

I have to confess that my baby was a mistake. We all make them, don’t we? I’m not wicked through and through or anything. I just fell for a handsome, laughing boy and let him under my skirt. He did not force me – far from it. He was a groom in the palace stables and I enjoyed our romps in the hayloft as much as he did. Priests go on about carnal sin and eternal damnation, but they do not understand about being young and living for the day.

I am not pretending I was ever beautiful but at fourteen I was not bad looking – brown haired, rosy-cheeked and merry-eyed. A bit plump maybe – or well-covered as my father used to say, God bless him – but that is what a lot of men like, especially if they are strong and muscular, like my Jean-Michel. When we tumbled together in the hay he did not want to think that I might break beneath him. As for me, I did not think much at all. I was intoxicated by his deep voice, dark, twinkling eyes and hot, thrilling kisses.

I used to go and meet him at dusk, while my parents were busy in the bake-house, pulling pies out of the oven. When all the fuss about ‘sinful fornication’ had died down, Jean-Michel joked that while they were pulling them out he was putting one in!

I should explain that I am a baker’s daughter. My name is Guillaumette Dupain. Yes, it does mean ‘of bread’. I am bred of bread – so what? Actually, my father was not only a baker of bread but a patissier. He made pastries and wafers and beautiful gilded marchpanes and our bake-house was in the centre of Paris at the end of a cobbled lane that ran down beside the Grand Pont. Luckily for us, the smell of baking bread tended to disguise the stench from the nearby tanning factories and the decomposing bodies of executed criminals, which were often hung from the timbers of the bridge above to discourage the rest of us from breaking the law. In line with guild fire-regulations, our brick ovens were built close to the river, well away from our wooden house and those of our neighbours. All bakers fear fire and my father often talked about the ‘great conflagration’ before I was born, which almost set the whole city ablaze.

He worked hard and drove his apprentices hard also. He had two – stupid lads I thought them because they could not write or reckon. I could do both, because my mother could and she had taught me – it was good for business. All day the men prepared loaves, pies and pastries at the back of the house while we sold them from the front, took orders and kept tallies. When the baking was finished, for half a sou my father would let the local goodwives put their own pies in the ovens while some heat still remained. Many bakers refused to do this, saying they were too busy mixing the next day’s dough, but my father was a kind soul and would not even take the halfpenny if he knew a family was on hard times. ‘Soft-hearted fool!’ my mother chided, hiding a fond smile.

He was not soft-hearted when she told him I was pregnant though. He called me a whore and a sinner and locked me in the flour store, only letting me out after he had visited Jean-Michel’s parents and arranged for him to marry me.

It was not very difficult. No one held my lover at knife-point or anything and afterwards Jean-Michel said he was quite pleased, especially as it meant he could share my bed in the attic above the shop. He had never slept in a real bed because until he went to work at the king’s stables, where he dossed down in the straw with the rest of the boy-grooms, he had slept on the floor of his father’s workshop with his three brothers. The Lanières were harness-makers and operated from a busy street near Les Halles, where the butchers and tanners plied their odorous trades, making leather readily available. With three sons already in the business, there was no room for a fourth and so, when he was old enough, Jean-Michel was articled to the king’s master of horse. It was a good position for he was strong and nimble, but also kind and gentle-voiced. Horses responded to him and did his bidding.

The royal stables were busy day and night and inevitably the apprentices got all the worst shifts, so after we married we only shared my bed when he could wangle a night off. Otherwise it was a tumble in the hayloft or nothing – mostly nothing as I grew larger. When my father sent a message that my birth-pains had started, Jean-Michel rushed from the palace, hoping to hear the baby’s first cry but instead he wept with me in the mournful silence.

Men don’t feel these things the same as women though, do they? After an hour or so, he dried his eyes, blew his nose and went back to the stables. There was no funeral. I wanted to call the child Henri after my father, but when the priest came it was too late for a baptism and Maître Thomas took the tiny body away to the public burial ground for the unshriven. I know it is foolish but all these years later I sometimes shed tears for my lost son. The Church teaches that the unbaptised cannot enter heaven but I do not believe it.

It must be obvious already that I was an only child. Despite ardent prayers to Saint Monica and a fortune spent on charms and potions, my mother’s womb never quickened again. Perhaps because of this, when my baby died she thought I might have lost my only chance of motherhood so, when she could no longer bear the sound of my sobbing, she walked along to the church and asked the priest if there was any call for a wet-nurse.

It so happened that Maître Thomas had a brother in the queen’s household, and later that day the appearance in our lane of a royal messenger brought all the neighbours out to gawp at his polished ebony staff and bright-blue livery with its giddy pattern of gold fleur-de-lis. When my mother answered his impatient rap, he wasted no time on a greeting, merely demanding imperiously, ‘Does your girl still have milk?’ as if he had called at a dairy rather than a bakery.

The first I knew of anything was when my mother’s moon-face rose through the attic hatchway, glowing in the beam of her horn lantern. ‘Come, Mette,’ she said, scrambling off the ladder. ‘Quick, get yourself dressed. We’re going to the palace.’

Still befuddled with grief, I stood like a docile sheep while she squeezed my poor flabby belly and leaking breasts into my Sunday clothes and pushed me out into the daylight.

The route to the king’s palace was familiar from my frequent love-trysts with Jean-Michel. We walked east along the river where the air was fresh and the sky was a bright, uncluttered arc. In the past I had often lingered to watch the traffic on the water; small fishing wherries with fat-bellied brown sails, flat-bottomed barges laden with cargo and occasionally, weaving between them, a gilded galley bedecked with livery, its crimson blades dripping diamond droplets as it ferried some grandee to a riverside mansion.

It was in these leafy suburbs close to the new city wall that many imposing town-houses had been built by the nobility. The highest tower in Paris was to be found there, rising brand-new and clean-stoned above the Duke of Burgundy’s Hôtel d’Artois. In the shadow of the ancient abbey of the Céléstins lay the impressive Hôtel de St Antoine where lived the king’s brother, the Duke of Orleans. Neighbouring this, however, and overlooking the lush meadows of the Île de St Louis, was the king’s magnificent Hôtel de St Pol, the largest and most sumptuous residence of them all. It sprawled for half a league along the north bank of the Seine, the spires and rooftops of a dozen grand buildings visible behind a high curtain wall of pale stone which was fortified with towers and gatehouses constantly a-flutter with flags and banners.

Old men in the market-place told how the present king’s father, King Charles V, distraught at losing eight consecutive offspring in their infancy, had eyed his nobles’ airy new mansions with envy and went about ‘acquiring’ a whole parish of them for himself around the church of Saint Pol. Then he had them linked with cloisters, embellished with Italian marble, surrounded with orchards and gardens and enclosed within one great wall, thus establishing his own substantial palace in a prime location and leaving his disgruntled vassals to rebuild elsewhere. This regal racketeering was justified on the grounds that the king’s next two sons survived, born and raised in much healthier surroundings than the cramped and fetid quarters of the old Palais Royal.

For my trysts with Jean-Michel I used to slip into the palace by a sally gate in the Porte des Chevaux, where the guards came to know me, but the queen’s messenger led my mother and me to the lofty Grande Porte with its battlemented barbican and ranks of armed sentries, his royal staff acting like a magic wand to whisk us unchallenged through the lines of pikes into a vast courtyard. Men, carts and oxen mingled there in noisy confusion. I was kept so busy dodging rolling wheels and piles of steaming dung that I failed to notice which archways and passages we took to reach a quiet paved square where a fountain played before a fine stone mansion. This was the Maison de la Reine where the queen lived and held lavish court and where, presumably, since she’d produced so many children, she received regular visits from the king, although rumour had it that he had not fathered her entire brood.

The grand arched entrance with its sweeping stone staircase was not for the likes of us, of course. We were led to a ground-level door alongside a separate stone building from which belched forth rich cooking smells. The heat of a busy kitchen blasted us as we were brought to a halt by a procession of porters ferrying huge, loaded dishes up a spiral tower-stair to the main floor of the mansion. The queen’s household was dining in the great hall and it was several minutes before we were beckoned to follow the final steaming pudding up the worn steps to a servery, where carvers were swiftly and skilfully dissecting roasted meats into portions. The aroma was mouth-watering even to my grief-dulled senses and my mother’s long, appreciative sniffs were audible above the noise made by the hungry gathering on the other side of the screen that hid us and the carvers from them.

We were ushered through a door beyond the servery and down a narrow passage into a small, cold chamber lit only by a narrow shaft of daylight from a high unglazed window. Here our escort brusquely informed us that we should wait and then departed, closing the door behind him.

‘What are we doing here?’ I hissed to my mother, stirred at last into showing some interest in our circumstances.

‘Not being fed, obviously,’ she complained. ‘You would have thought they could spare a bit of pudding!’ Huffily she sank onto a solitary bench under the window and arranged her grey woollen skirt neatly around her. ‘Come and sit down, Mette, and compose yourself. You want to make a good impression.’

Gingerly I lowered myself onto the bench beside her. It was not many hours since I’d given birth and to sit down was painful. ‘Impression?’ I echoed. ‘Who should I make an impression on?’ My breasts throbbed and I was becoming distinctly nervous.

‘On Madame la Bonne, who runs the royal nursery.’ Now that she had got me here, my mother risked divulging more information. ‘She needs a wet-nurse for the new princess.’

‘A wet-nurse!’ I echoed, wincing as I recoiled along the hard bench. ‘You mean … no, Ma! I cannot give suck to a royal baby.’

My mother drew herself up, both chins jutting indignantly from the tight frame of her goodwife’s wimple. ‘And why not, may I ask? Your milk is as good as anyone’s. Better than most probably, for you are young and well-nourished. Think yourself lucky. If they take you, you will have drawn the top prize. It might have been a butcher’s baby or a tax collector’s brat.’

I opened my mouth to protest that a baker’s daughter could hardly despise a butcher’s baby but swallowed my words as the door opened to admit a thin, erect woman of middle age and height, dressed in a dark wine-coloured gown with sweeping fur-lined sleeves. The eaves of her black gable-headdress shadowed a pinched, rat-like face and she looked so unlike anyone’s idea of a children’s nurse that my mother and I were both struck dumb. We stood up.

‘Is this the girl?’ the woman asked bluntly. Her lip curled. ‘Ah yes, I can see it is.’

Following her disdainful gaze, I glanced down and saw that damp milk-stains were beginning to spread over the front of my bodice. Shame and grief sent fresh tears coursing down my cheeks.

‘What is your name?’ demanded the fur-sleeved lady but any reply I might have made was forestalled as she grabbed me by the arm, pulled me under the beam of light from the window and wrenched my mouth open, peering into it.

My mother spoke for me. ‘Guillaumette. My daughter’s name is Guillaumette.’ She frowned at the crude treatment I was receiving but was too over-awed to object.

Madame la Bonne grunted and released my jaw. ‘Teeth seem good,’ she observed, aiming her rodent nose at my damp bodice and taking a long investigative sniff. ‘And she smells clean. How old is she?’

‘Fifteen,’ replied my mother, trying to edge her ample frame between me and my tormentor. ‘It was her first child.’

‘And it is dead, I hope? We do not want any common nursling bringing disease into the royal nursery.’ My instantly renewed sobs appeared to convince her of this for she nodded with satisfaction. ‘Good. We will take her on trial. Five sous a week and her bed and board. Any sign of ague or milk fever and she is out.’ Before my mother could question these terms, the dragon-lady turned to address me directly. ‘You should stop snivelling, girl, or your milk will dry up and you will be no use to anyone. The queen was delivered at the hour of sext and the princess needs suck at once. I will send someone to collect you.’

Not waiting to hear whether or not her offer was accepted, Madame la Bonne swept out of the room. My mother stared after her, shaking her head, but the mention of five sous a week had struck a chord. Although my eyes were blurred with tears, I caught the commercial glint in hers as she calculated how much this would add to the family coffers.

‘We had best say goodbye then,’ she said gruffly, kissing my wet cheeks. ‘It is a good opportunity, Mette. Blow your nose and make the most of it. Remember Jean-Michel is not far away. You will be able to visit him between feeds.’ Gently, she wiped away my tears with the edge of her veil. ‘It will be hard at first but who knows where it could lead? You will get used to it and the baby needs you. You heard the lady.’

I nodded, barely comprehending. When another liveried servant arrived to take me away I followed him without a backward glance. My head was spinning and my breasts felt as if they would burst. Relief from that piercing ache would be welcome, no matter what followed.

They put the baby in my arms and unlaced my bodice. I had no idea what to do but the midwife was there, an ancient crone who must have witnessed a thousand births, and she showed me how to hold the tiny bundle so that my oozing nipple was available to the seeking mouth. At first the infant could not clamp the slippery teat between her hard gums and she yelled with frustration while fresh tears poured down my face.

‘I cannot do it!’ I cried. ‘She does not like me.’

The midwife wheezed with amusement. ‘What does she know about liking?’ she said, bringing the baby’s head and my breast together like a pair of ripe peaches. ‘All she wants is to suck. She is a little poppet this one, healthy as a milkmaid and strong as a cobweb. Just you sit quiet now and wait for her to latch on. She will. Oh yes she will!’

She did. Very soon she was fastened to my nipple like a pink leech and I could feel the painful pressure dropping. I stared down at the swaddled crown of her head and noticed a tiny wisp of pale gold hair had slipped between the linen bands. Otherwise, she seemed anonymous, almost inhuman, like one of the gargoyles on the roof of our church. I shivered at the sudden notion that she might be a creature of the devil. Supposing I had been foist with a succubus?

I closed my inflamed eyes and took a deep breath. Of course she was not a demon, I told myself firmly. She was a baby, a gift of God, a morsel of human life that was strangely and avidly attached to my body.

Gradually, I began to feel a steady and reassuring rhythm in the mysterious process of giving suck, a regular swishing sound like the soft hiss made by the surge of the tide on the Seine mudflats. I sensed that the child and I were sharing a universal pulse, joined together in the ebb and flow of life. And as my milk flowed, my tears dried. I did not stop grieving for my lost son but I no longer wept.

2 (#ulink_a4a1ab3e-f441-5758-aebc-c7503694b6a9)

How can we ever know what life has in store for us? My new situation nearly ended as abruptly as it had begun, because the next morning some of my breast milk oozed onto the white silk chemise that had been pulled over the baby’s swaddling in preparation for her baptism. I trembled, awaiting the full power of the rat-woman’s wrath, but luckily the stain was quickly hidden under the folds of an embroidered satin christening robe and then, crowned with a tiny coif of lace and seed-pearls, the baby was carried off to the queen’s chapel. Later we were told she had been baptised Catherine after the virgin martyr of Alexandria, whose staunch Christian faith had not even been broken by torture on the wheel.

In the beginning I did not really have much to do with Catherine, except to let her suck whenever she cried for the breast. Madame la Bonne insisted on attending to the swaddling herself. She changed it every morning, convinced that only she knew the secret of how to make the royal limbs grow straight. Two dim-witted girls were in charge of washing and dressing and rocking the cradle, which they did with scant care or attention, it seemed to me. After a few days the governess must have decided I could stay, for my straw mattress and Catherine’s crib were carried into a small turret room, separated by a thick oak door from the main nursery. I was told that this arrangement was in order to prevent the baby’s cries waking the other children but I was far from happy. Terrified of the responsibility of looking after a royal baby alone throughout the night, I became jaded from lack of sleep, home-sick and heart-sick for my own lost son. Yet none of this seemed to affect my milk, which flowed profuse and steady, like the Seine beneath the turret window.

My experience of royal nurseries was nil but even so this one struck me as distinctly odd. Here we were in the palace of reputedly the most profligate queen in Christendom and yet, apart from the pearl-encrusted christening robe which had been swiftly borne away for safekeeping, I could find no evidence of luxury or wealth. There were no fur-lined cribs or silver rattles or chests full of toys, and the rooms, located in a separate tower to the rear of the queen’s house, were cold and bare. Although my turret had a small grate and a chimney, there were no fires even to warm the newborn child, no hangings to keep out the autumn draughts and only smoky tapers and oil lamps to light the lengthening nights. Food came up from the queen’s kitchen, but it was nothing like the fare I had seen on the day of my arrival. No succulent roasts or glistening puddings for us; we ate potage and bread messes, washed down with green wine or buttermilk. Occasionally there was some cheese or a chunk of bacon but rarely any fresh meat or fish. We might have been living in a monastery rather than a palace.

The reason was not hard to find, for in contrast with her name, there was very little that was good about Madame la Bonne. I quickly understood that her first concern was not the welfare of the royal children but the wealth of the royal governess. I was to learn that any savings she could make on the nursery budget went straight into her own pocket, which was why she had employed me. A courtier’s wife would have been more appropriate as wet-nurse for a princess, but a lady of rank would not only command higher pay, she would also have powerful friends, and Madame la Bonne’s plans and schemes depended on no one with any connection to power or authority ever coming near the place; none ever visited, not the master of the household or the queen’s secretary or chancellor, or even one of their clerks and certainly not the queen herself.

As well as Catherine, there were three other royal children in residence. The oldest was Princess Michele, a solemn, rather plain-looking girl of six who was always trying to keep the peace between her two younger brothers, the Princes Louis and Jean. Louis was the dauphin, the unlikely heir to the throne, a skinny, tow-headed four-year-old with a pale complexion and a chronic cough whose clothes were grubby and too small. However, I observed that he had a quick brain and an active imagination, which often led him into mischief. His brother Jean was a bull-headed terror, a ruffian even at three, darker and sturdier than his brother and more headstrong. You could be sure that if Louis started some mischief, Jean would continue it beyond a joke. After I caught him dropping a spider into Catherine’s crib, I decided to keep a very close eye on Monsieur Jean! I knew that if any harm came to the baby, the blame would instantly be laid on me, not on her infant brother.

Being an only child, I had never had much to do with other children and yet, to my surprise, having been thrown into close contact with these as-good-as-motherless youngsters, I found I knew instinctively how to handle them. Oddly, I felt no similar instinct when it came to Catherine. I could not help nursing a certain resentment that she was alive while my own baby was dead and I could not see past those horrible swaddling bands, which seemed to squash all the character out of her. Sometimes it felt as if I was suckling a sausage. Besides, I grew restless just sitting around waiting to open my bodice, so in between Catherine’s feeds I started playing with the older children.

I could see that the boys’ naughtiness sprang from boredom rather than wickedness. They were bright and spirited but the two giggling nursemaids were too busy gossiping or sneaking out to meet their lovers to have much time for their charges. They would plonk food on the table but they rarely brought water to wash the children and never talked or played with them. Madame la Bonne had pared their wages to the minimum and, like my mother always said, ‘If you pay turnips you get donkeys’.

To start with, the children were wary of me but soon Michele opened up, being touchingly grateful for some attention. A slight, mousy little girl, she had fine, dirty blonde hair that was always in a tangle because Louis had thrown the only hairbrush out of the window in a tantrum and Madame la Bonne had chosen not to replace it. Although outwardly placid, she was terribly insecure, shying at raised voices, assuming slights where there were none and fearful that at any moment she might be whisked away to marry some prince in a foreign land. When I tried to reassure her that she was too young for that, she blinked her solemn sea-green eyes and shook her head.

‘No, Mette.’ My full name, Guillaumette, was too much for young tongues to master. ‘My sister Isabelle was only eight when she went away to England.’

I remembered that departure. I had watched Princess Isabelle being paraded through the streets of Paris at the time of her proxy marriage to King Richard of England, a tiny doll-like figure propped up in a litter, weighed down with furs and jewels, and it had never occurred to me or to any of us in that noisy crowd of citizens how frightened she must have been, being carted off to a strange country to live with a man old enough to be her grandfather. And what had become of that little bride? An English lord named Bolingbroke had stolen King Richard’s throne and his abandoned child-queen was still languishing somewhere across the Sleeve, her future uncertain. I realised that Michele was right to be frightened.

The boys took longer to respond to my overtures. Prince Louis’ insecurities sprang from a different source but were equally deep-seated. He was haunted by a ghost. At the start of the year his older brother Charles had died of a sudden fever and the whole of France had plunged into mourning. Unlike his younger siblings, the nine-year-old dauphin had been doted on by Queen Isabeau, kept beside her at court, given his own household and showered with gifts and praise. He was shown off to every high-ranking visitor and proclaimed ‘the glorious future of France’! Even my down-to-earth mother had joined the crowds cheering him in the streets, raining blessings on his bright golden head.

It was the sweating sickness that carried him off. One day he was riding his pony through the city and the next he was dead, consumed by a raging fever. Queen Isabeau collapsed and the king succumbed to one of his devilish fits. I suppose during the months that followed, the new dauphin might have expected to be whisked off to the life of luxury and privilege that his brother had enjoyed, but this did not happen and so, every time he was reprimanded or denied something, Louis would throw a tantrum, hurling himself to the ground shrieking ‘I am the dauphin! I am the dauphin!’ This was always a source of great entertainment for Jean, who would squat down nearby and watch with undisguised glee as Louis drummed his heels and screeched. I never saw him try to comfort his brother. Even in infancy Jean was an odd, isolated boy.

Madame la Bonne had devised her particular way of ensuring that the sound of Louis’ tantrums did not carry outside the nursery. The first time I heard his blood-curdling yells, I rushed in panic to the big day-room and was horrified to see the governess lift up the screaming little boy, bundle him into a large empty coffer, close the lid and sit on it.

‘Madame, really you cannot …!’ I protested.

‘Presumptuous girl!’ she snapped. ‘Be silent. You are here to give suck, nothing more. I advise you to keep your mouth shut and your bodice open or another wet-nurse will be found.’

Beneath her skinny rump Louis’ muffled cries dwindled into whimpers and I was forced to retreat to my turret. It was not until much later, when I was convinced he must be dead, that the governess let the little boy out. Peeping cautiously around the door I saw him emerge trembling and gasping and run to a far corner to press his tear-stained face against the cold stone wall. In his terror he had wet himself but no one offered him dry hose. No wonder he always stank. The governess caught me peeking and gave me another warning glare, so I fled.

A month or so after her birth, Catherine started sleeping for longer periods and I was able to risk my first visit to the stables. Always a man of action rather than words, Jean-Michel greeted me shyly and immediately led me up the ladder to the hay-loft and began shifting bundles of fodder to create a private corner for us, away from the prying eyes of his fellow-grooms. The rows of horses in the stalls below radiated warmth and although at first we talked awkwardly and strangely, it wasn’t long before we were exchanging eager kisses. The result was predictable. I am sure I don’t need to go into detail. I was fifteen and he was eighteen and after all we were married … it wasn’t natural for us to remain sad and celibate.

Afterwards we talked some more, carefully avoiding the subject of our dead baby. I told Jean-Michel how Madame la Bonne’s greed made life so cold and comfortless in the royal nursery. By now it was early December and the nights were freezing in the turret chamber. Being a kind-hearted lad, he exclaimed indignantly about this and the next time I came he presented me with some bundles of firewood. ‘Smuggle them in under your shawl. No one will see the smoke if you burn it after dark,’ he suggested.

So when Catherine next woke in the small hours, making restless hungry sounds, I lit a taper with my flint, pulled straw from my mattress for kindling, piled some sticks on top and set the taper to them. As I did so I noticed that her swaddling had come loose and a strip of damp linen was dangling down. On an impulse I pulled it and all at once I could feel her legs begin to kick. In the light of the fire I could see pleasure blaze in her deep-blue eyes and I made an instant decision.

I pulled my bed in front of the hearth, spread the blanket over it and laid Catherine down, eagerly removing the rest of the offensive linen bands. I prayed that no one would take notice of her squalls of protest as I used the icy water from my night-jug to clean her soiled body, and soon the warmth of the flames silenced her cries and she began to stretch and kick, luxuriating in the dancing firelight. Her little arms waved and I bent to smile and coo at her, blowing on her neck and belly to tickle her soft, peachy skin so that she squirmed and burbled with delight.

The previous summer, walking among the wildflowers on the riverbank, I had watched entranced as a butterfly emerged into the sunshine, the full glory of its multicoloured wings gradually unfurling before my eyes. In those first moments by the fire Catherine reminded me of that butterfly. For the first time her big blue eyes became sparkling pools, glowing with life, and her soft mop of flaxen hair, for so long flattened and confined, began to spring and curl. Then, as I bent low and whispered soft endearments into her ear, I was rewarded with a wide, gummy smile.

All the love I had been unable to lavish on my own baby seemed to burst like a dam inside me. I wanted to shout with joy but instead, mindful of the ‘donkeys’ sleeping in the next room, I swept Catherine up and pressed her little body tightly against mine, whirling her round in a happy, silent dance. I could feel her heart fluttering under my hands and, tiny and helpless though she appeared, she put a powerful spell on me. From that moment I was no longer my own mistress. In the leaping firelight I gazed at that petal-soft, bewitching cherub and became her slave.

When I again wrapped her warmly and began to feed her, giving suck was an entirely new experience. At my breast I no longer saw a pink leech but a rosy angel with a halo of pale hair and skin like doves’ down. Now that her limbs were free, she pushed one little hand against my breast and kneaded it gently, as if caressing and blessing me at the same time and under the power of this benison the milk that flowed from me seemed to contain my very heart and soul.

3 (#ulink_ec88a3e7-4a98-5791-886e-59fb1cb959a5)

‘The king’s in the oubliette again,’ announced Jean-Michel one afternoon when we were alone together. The ‘oubliette’ was servants’ slang for the special apartment set aside to contain the monarch during his ‘absences’.

‘They carted him off there yesterday afternoon. Apparently he drew his dagger in the council and started slashing about with it wildly, so they had to disarm him and tie him up.’

‘God save us! Was anyone hurt?’ I asked with alarm.

‘Not this time.’

‘Have people been injured in the past then?’

‘Well, they try to hush it up but one or two chamberlains have mysteriously disappeared from circulation.’

‘You mean they have been killed?’ I squeaked, incredulous.

‘No one has ever admitted it, but …’ Jean-Michel spread his hands. ‘Mad or not, he is the king. Who is going to accuse him of murder?’

I shivered. The closer I got to it, the more I was bewildered by the power of monarchy. Since I had been at the palace I had never laid eyes on the king – at least not as far as I knew. It had been drummed into me by Madame la Bonne that if I should happen to encounter anyone of rank, unless they spoke to me directly, I must avert my eyes and remove myself from their presence as fast as possible. Servants were issued with drab clothing; in my case a mud-coloured kirtle and apron and a plain white linen coif, and like all other palace menials I had perfected the art of scuttling out of sight at the merest flash of sparkling gems and bright-coloured raiment. So, even if I had glimpsed the king I would have been obliged to ‘disappear’ before I could distinguish him from any other peacock-clad courtier. Of course everyone knew of his recurring malady. One day he would be quite normal, eating and talking and ruling his kingdom, and the next he was reduced to a quavering, raving, deluded wreck, a state which might persist for any length of time, from a week to several months.

‘What happens now?’ I enquired.

‘The queen will pack up and go to the Hôtel de St Antoine,’ Jean-Michel said with a sly grin. ‘When her husband is out of the way, she jumps into bed with her brother-in-law.’

‘The Duke of Orleans!’ I exclaimed. ‘No! She cannot. It is a sin.’

‘Listen to Madame Innocente!’ teased Jean-Michel. ‘It is treason too, as it happens, but no one says “cannot” to Queen Isabeau. Who is going to arrest her? When the king is ill, she becomes regent.’

Now I was even more shocked. Did God not punish adultery? Did not the fiery pit yawn for the wife who bedded her husband’s brother?

‘What about hellfire?’ I protested. ‘Surely even queens and dukes go in fear of that.’

Jean-Michel shrugged. ‘I thought you would have realised by now that royalty does not live by the same rules as the rest of us. They can buy a thousand pardons and get absolution for absolutely everything.’ His brown-velvet eyes suddenly acquired a familiar gleam. ‘You look outraged, my little nursemaid. I like it when you get hot and bothered.’ He reached over to pull off my coif for he loved it when my dark hair tumbled down my back and it usually led to other items of clothing becoming disarranged.

I pushed his hand away, softening the rejection with a rueful smile. ‘No, Jean-Michel. I must go. Catherine might be crying for me.’

‘Catherine, Catherine!’ he mimicked, frowning. ‘All I hear about is Catherine.’ His tone was indignant but a note of indulgence lurked beneath. To look at him you would not think there was anything soft about Jean-Michel but I think he understood that I had come to love my little nursling the way I would have loved our own baby.

I scrambled up, brushing stalks off my skirt. ‘I will come again tomorrow,’ I promised, giving him a genuinely regretful look, for he was not alone in wanting to linger in our hayloft hideaway.

‘One day you must tell Mademoiselle Catherine what sacrifices we made for her!’ he caroled after me down the ladder.

As he had predicted, the queen did indeed de-camp to the Duke of Orleans’ mansion and their Christmas celebrations set the city abuzz. Night after night bursts of minstrel music drifted up to the nursery windows from lantern-decked galleys ferrying fancy-dressed lords and ladies to a series of entertainments at the Hôtel de St Antoine. Craning our necks through the narrow casement, we could just see the crackle and flash of fireworks and hear the roar of exotic animals, brought from the king’s menagerie to thrill the assembled guests. Jean-Michel reported that the taverns were full of minstrels and jongleurs who had converged on Paris in droves, drawn by the promise of lavish purses for those who impressed the queen.

It was a mystery to me why she did not include her children in all this fun. She did not even send them presents. The joy of Christmas barely touched the royal nursery. On the feast-day itself, Madame la Bonne pulled their best clothes out of a locked chest and took the children to mass in the queen’s chapel and I was allowed to sit at the back with the donkeys. Otherwise we might not even have known it was Christmas.

Our dinner was even worse than usual, consisting of grease-laden slops and stale bread, which the children understandably refused to eat. Only the Christmas pies I fetched from my parents’ bake house gave the poor mites a taste of good cheer.

By Epiphany the palace had ground to a halt. Madame la Bonne had gone to a twelfth-night feast at the house of one of her noble relatives, leaving the ‘donkeys’ in charge, and they had taken advantage of her absence to make themselves scarce as well. ‘You’ll be all right on your own, won’t you, Guillaumette?’ they said airily. ‘Just ask the guards if you need anything.’

The next morning the varlets who brought our supplies of food and water failed to turn up. I was alone with four royal children, no food, no warmth and no one to turn to. I was terrified. Only the sentries remained at their posts, guarding the entrance to the nursery as usual.

‘Nobody has been paid,’ one of them revealed bluntly, when I plucked up courage to ask where everyone was. ‘The master of the household has gone with the queen and taken all the clerks and coffers with him.’

‘Then why are you still here?’ I enquired.

The soldier’s sly grin revealed a row of blackened stumps. ‘The royal guard is paid by the Constable of France, God be praised – and he is an honourable man.’

‘Unlike the royal governess,’ I muttered. ‘I have not been paid for weeks.’

‘Best leave then, my little bonbon, like the rest of them,’ he wheezed in a foul-smelling chuckle. ‘Fools earn no favour.’

But how could I leave? How could I abandon four friendless and motherless children? I persuaded the guard to fetch us some bread and milk for the children’s breakfast and after the donkeys finally returned looking smug and dishevelled, I fed Catherine and left her sleeping while I sped home to the bakery and begged a basketful of pies and pastries from my mother. I told her the king’s children were starving in their palace tower.

It was no real crisis because Madame la Bonne returned from her social engagement and the meal deliveries, mean though they were, began once more. But there was still no sign of any laundry and I was sent to the wash-house to investigate. Overwhelmed by the acrid stench of huge bleaching vats overflowing with urine and the smelly heaps of dirty linen turning blue with mildew, I filched an armful of linen napkins when I spotted them and ran. I could wash the napkins daily and keep her clean. Without a supply of clean swaddling, Madame la Bonne could no longer truss the baby up every morning, so Catherine’s limbs were allowed to kick free and strong. Meanwhile her blonde curls rioted under the little caps I sewed for her. Ironically, during those dreadful weeks of winter she grew as bonny and plump as a bear cub.

But I felt sorry for the older children. They were cold and hungry and the only thing in plentiful supply was punishment. Whenever mischief flared, which it often did, especially between the boys, some new and vindictive retribution was devised by their governess. On several occasions I saw Jean struggling against tight bonds tying him to his chair, or Louis sitting down gingerly, his buttocks clearly smarting from a beating. I often saw his eyes glinting with resentful anger but he was only four, powerless to retaliate, and if he could have voiced a complaint, who would he have voiced it to? Perhaps the worst thing however, was the fact that their father’s oubliette was too close to the nursery tower and the inhuman noises which frequently erupted from that grim place were enough to freak young minds.

The general belief was that the king’s madness was caused by agents of the devil. Perhaps living close to the king, Madame la Bonne had been taken over by them as well. Sometimes I was sure I could hear their wings fluttering against the door and I scarcely dared to inhale for fear of contagion.

Jean-Michel told me that in the city taverns, out-of-work palace menials made easy ale-money telling lurid tales of black masses where sorcerers called up flocks of winged demons and sent them flying to infest the subterranean vault where the mad monarch was housed. I often heard the donkeys frightening each other with sightings of these imps. No wonder all the children had bad dreams and Jean wet his bed. As punishment, Madame la Bonne made him sleep on a straw mattress on the floor. At least she ordered the donkeys to wash his bedclothes and not me, but not until they reeked abominably.

The winter was stormy and snow-laden and the children hardly left the nursery for weeks but somehow, with the aid of my father’s pies, my stock of family fairy-tales and Jean-Michel’s pilfered firewood, we struggled through those cold, dark days. Then, at last, the season turned, the sun began to climb in the sky and the ice melted on the Seine. When the guilds of Paris began their spring parades and the blossom frothed in the palace orchards, the king suddenly regained his senses and the queen came back to the Hôtel de St Pol.

‘If she wants to be regent when he is ill, she has to live with the king when he is not,’ Jean-Michel observed sagely when I remarked on the speed of her return. ‘And believe me, she loves being regent.’

Of course she still came nowhere near the nursery, but at least she brought back her coffers and courtiers and Madame la Bonne was forced to start paying servants to bring us food and supplies instead of relying on free hand-outs from my father’s bakery. It had not escaped my notice that the rat-woman must have amassed a great deal in unpaid wages over the winter so I summoned my courage and demanded the sum I was owed.

Madame la Bonne simply laughed in my face. ‘Four marks! Whatever made a chit like you think she could reckon?’ she mocked. ‘Five sous a day do not come to four marks. You are not owed a quarter of that sum.’

Despite my best endeavours, I only managed to prise one mark out of her. When I showed it to my mother I think her anger was more due to the governess’ slighting of my education than her act of blatant cheating. ‘I suppose we should be grateful to get that much,’ she said with resignation. ‘They are all at it. Every shopkeeper and craftsman in the city complains about the “noble” art of short-changing.’

As it grew warmer, the palace became like a fairground. The gardens filled with gaily dressed damsels and strutting young squires, laughing and playing sports. Music could be heard drifting over walls and through open windows, and court receptions were held out of doors, under brightly painted canopies. It made life difficult for us menials, as we constantly had to change direction to get out of the way of groups of courtiers making their way to these receptions or to the pleasure gardens and tilting grounds. Often it took me twice as long to get to the stables in order to meet Jean-Michel because I would have to wait with my face to the wall while processions of chattering ladies and gentlemen ambled past me in the cloisters. At least I was able to take the children out to play every day, although Madame la Bonne made it a strict rule that we were only to go to the old queen’s abandoned rose garden because we could get there from the nursery without encountering anyone of consequence. She did not want a nosy official querying the state of the royal children’s clothing, did she? Nor – heaven forefend – did she want some inadvertent meeting between the queen and her own offspring!

As for the queen herself, as the summer progressed and the August heat became stifling in the city, she set off in a long procession of barges for the royal castle at Melun, further up the Seine. Soon after her departure, word spread that she was pregnant and, in view of the timing, rumour again flared that the child was not the king’s but had been fathered by the Duke of Orleans during the last royal absence. I did my own calculations and came to the conclusion that she could just about be given the benefit of the doubt. Perhaps the king did the same because there was no sign of any rift between himself and his brother or his queen.

At about the same time, I began to notice certain changes in my own body. It was popular belief that nursing a child prevented the next one coming along, but this did not hold true for me. My mother put it all down to Saint Monica of course and Jean-Michel boasted to his stable-mates that it took more than a royal nursling to stop him becoming a father!

Madame la Bonne said nothing until it became obvious that I was breeding, when she sniffed and said, ‘It’s time Catherine was weaned anyway. You can leave at Christmas.’

Remembering the miseries of the previous Christmas, I hastily assured her that since my baby was not due until spring, I could stay well into the New Year. I could not bear to think of Catherine having only the donkeys and Madame la Bonne to look after her, but I knew I had to steel myself for the inevitable parting. Perhaps, had it not been for my own babe, I might have timed Catherine’s weaning so that I could have remained as wet nurse for the queen’s new child, but I knew that no lowborn baby would be allowed to stay in the royal nursery or share the royal milk supply. Our time together was drawing inexorably to a close. Soon after her first birthday, Catherine began to take wobbling steps and I started feeding her bread and milk pap, and by February, when the queen’s new son was born, I had prepared her as best I could for the arrival of her new sibling.

Far from questioning the paternity of his latest offspring, the king was so delighted to have another son that he insisted he should be called Charles, apparently unconcerned by the fact that both previous princes of that name had died young. Like all his siblings before him, this new Charles popped obligingly from the queens womb, was baptised in silk and pearls and then brought to the nursery, well away from his parents’ attention. His wet-nurse was another nobody, like myself, who could be exploited by Madame la Bonne but, I like to think unlike myself, she was a timid individual who took no interest in the older children and confined herself to suckling the baby and gossiping with the donkeys. She was a deep disappointment to me, because I had hoped she might be the motherly type who would give Catherine the cuddles she would need after I was gone.

My little princess now toddled about on dimpled legs, a delightful bundle of energy who giggled and chattered around my skirts all day. I could not imagine life without her, but there was no alternative. It was a beautiful spring day when, forcing a bright laugh and planting a last kiss on her soft baby cheek, I left Catherine playing with her favourite toy – one of my own childhood dolls. Once clear of the nursery, I became so blinded by tears that Jean-Michel had to lead me home.

I had the consolation a month later of giving birth to my own healthy baby girl who, the Virgin be praised, breathed and sucked and wailed with gusto. We named her Alys after Jean-Michel’s mother, who adored her, having raised only boys herself. I loved her too of course but, although I suckled her and tended her every bit as scrupulously as I had Catherine, I admit that I probably never quite let her into the innermost core of my heart, where my royal cuckoo-chick had taken residence.

To many I must seem an unnatural mother, but I looked at it like this: Alys had a father who thought the sun and moon rose in her eyes and two doting grandmothers. She didn’t need me the way Catherine did. As the summer passed and the days began to shorten once more, I thought constantly of my nursling. While dressing baby Alys and tucking her into her crib, I wondered who was doing this for Catherine. Was anyone cuddling her and singing her lullabies? Would they comb her hair and tell her stories? I saw her face in my dreams, heard her giggle in the breeze and her unsteady footsteps seemed to follow me about.

No one understood how I felt except my mother, bless her, who said nothing but bought a cow and tethered it on the river bank behind the bakery ovens. When Alys was six months old, I weaned her onto cow’s milk and went back to the royal nursery. I know, I know – I am unchristian and unfeeling – but both the grandmothers were delighted to have a little girl to care for and I could no longer ignore my forebodings about Catherine.

Dry-mouthed with apprehension, I approached the guards at the nursery tower. Suppose they did not recognise me, or were too honest to resist the bribes of pies and coin I had brought? Things had not changed in that respect however, and I was soon quietly entering the familiar upper chamber. But how she had changed, my little Catherine! Instead of the sturdy, merry-eyed toddler I had left, I found a moping moppet, thin, dull-eyed and melancholy with lank, tangled curls and a sad, pinched face. When she saw me she jumped straight down from the window-seat where she had been glumly fiddling with the old doll I had left her and ran towards me shouting, ‘Mette! Mette! My Mette!’ in a sweet, piping voice.

My heart did somersaults as she flung herself into my arms and clung to my neck. I was astounded. How did she know my name? She had been too young to speak it when I left the nursery and surely no one else would have taught it to her. Yet there it was, spilling joyfully off her tongue. Tears streaming down my cheeks, I sank onto a bench and hugged her, murmuring endearments into her shamefully grubby little ear.

I was brought down from the euphoria of reunion by a familiar voice observing with undisguised sarcasm, ‘Well this is a touching sight.’ Madame la Bonne had been sitting at a lectern under the window with Michele – I had, it seemed, interrupted her reading aloud in Latin – but now the governess moved across the room to stand over me wearing her usual disapproving expression. ‘Does this mean you have lost another baby, Guillaumette? Rather careless is it not?’

I stood up and deposited Catherine gently on the floor, where she clung tightly to my skirt. I smiled at Michele. It was difficult to swallow my anger at this heartless enquiry, but I knew I must if I wanted to stay. ‘No, Madame. My daughter thrives with her grandmothers. Her name is Alys.’ To Michele I said, ‘I’m glad to see you are still here, Mademoiselle.’

I exchanged meaningful looks with the solemn princess, who had grown significantly since I had last seen her. No one else appeared to have noticed this fact however, for her bodice was straining its stitches and her ankles protruded from the hem of her skirt.

‘We are all still here, Mette. Louis and Jean have a tutor now though.’

‘And your lesson should not be further interrupted,’ complained Madame le Bonne, glaring down her nose at me. ‘If you can keep Catherine quiet, you may take her over there for a while, Guillaumette.’ She pointed to the other window recess, where I had played so many games with the children in the past. ‘Princesse, let us continue your reading.’

Michele dutifully returned her attention to the heavy leather-bound book on the lectern and I took Catherine’s hand and retreated gratefully to the other side of the room. There were two windows in this upper chamber and the depth of their recesses meant that one was almost out of sight of the other.

Almost, but not quite; I could just see the governess sitting poker-faced throughout the next hour, doubtless pondering the implications of my arrival while she lent half an ear to Michele’s hesitant recital. Unbeknown to me, one of the ‘donkeys’ had run off with her varlet lover and my arrival had handed the governess a heaven-sent opportunity.

At the end of the lesson she left Michele and approached us. To my dismay I felt Catherine instinctively shrink from her presence.

‘The younger children need a nursemaid, Guillaumette. You can start straight away. Of course you will not be paid as much as you were as a wet-nurse. Three sous a week, take it or leave it.’

I knew that the chances of being paid anything like that sum were slim but I did not care. ‘Thank you, Madame,’ I said, rising and bowing my head. ‘I will take it.’ Hidden by the folds of my skirt, I squeezed Catherine’s little hand in triumph.

Within a week she was the sunny, laughing infant she had been before I left. Even Louis and Jean seemed pleased to see me. They lived separately from their sisters now, on the ground floor of the tower and were subject to a strict regime of study and exercise supervised by one Maître le Clerc, a supercilious scholar who wore the black robes of a cleric and one of those linen coifs with side flaps, which left his hairy ears exposed. I was intrigued to learn that Louis was already managing to construct simple sentences in Greek and Latin but unsurprised to hear that Jean was constantly being punished for his academic shortcomings. Supervising his bedtime one evening I glimpsed red weals on his legs and buttocks and despised the high-nosed tutor even more. However, at least he had introduced books to the nursery. Most girls of seven might have preferred stories or poetry but quiet, studious Michele was quite content with the worthy, religious tracts that he selected for her from the famous royal library in the Louvre.

I suspected that the governess and tutor might be related. They were certainly cast in the same mould for I soon learned that Maître le Clerc was as adept as Madame la Bonne at filling his own coffers. I confess I closed my eyes to their thieving ways. I had promised Catherine I would never leave her again. The children needed someone who was on their side; someone who would look out for them, encourage the boys not to fight, tell them jokes, bring them honeyed treats from the bakery. So we all rubbed along, playing what effectively amounted to blind man’s buff for nearly two years. Then, with the suddenness of a whirlwind, our lives were dismantled.

4 (#ulink_4d4d7f04-7d6e-58f4-bf8e-48f4454d84db)

In late August of 1405, a searing heat wave had caused trees to wilt and stone walls to shimmer. In the hope of catching an afternoon breeze off the river, I had taken the children to the old pleasure garden which ran down to a river gate. Planted on the orders of the king’s mother, Queen Jeanne, and sadly neglected since her death, it was smothered with overgrown roses which clambered about tumbledown arbours, making perfect haunts for Catherine’s imagined fairies and elves. As always when she played, little Charles shadowed her like a small lisping goblin, tottering determinedly on skinny legs in wrinkled, hand-me-down hose. Catherine loved him, though no one else seemed to, always comforting him when he cried.

In her usual quiet way Michele perched sedately on a bench under a tree and immersed herself in Voraigne’s Legendes d’Or and I am ashamed to say that as I sat with my back against a sun-baked wall, lulled by the murmuring of bees, I drifted off to sleep. I did not doze for long however, because Louis, little menace that he was, took advantage of my lapse to creep up and drop something wriggly and bristling down the front of my chemise. Roused by a stinging sensation between my breasts, I squealed and sprang behind some bushes, tearing open the laces in order to delve into my bodice while the boys screamed with delight. Shuddering, I removed a hairy black caterpillar and tossed it away. An itchy rash had already appeared on the tender damp flesh and, mortified, as I re-tied the laces of my bodice I was already rehearsing the rollicking I was going to deliver to the young princes when their giggling ceased abruptly. Emerging red-faced from my refuge, I stared open-mouthed at the sight that met my eyes.

It was as if a flutter of giant butterflies had alighted in the garden. The guards had rushed to open the old gate that led to a little-used dock on the riverbank and through it was advancing a procession of ladies and gentlemen clad in the height of fashion and chattering and laughing together. The gilded galley from which they had disembarked could be seen bumping gently against the landing stage, while a trio of escorting barges drifted in mid-river, each carrying a score or more of arbalesters and men-at-arms. Rooted to the spot, the children stood gawping like street urchins.

The half dozen ladies of the party wore full-skirted gowns in rainbow hues with high waists and trailing sleeves and they walked with a studied, laid-back gait, carefully balancing an array of architectural headdresses – steeples, arches and gables – glittering with jewels and fluttering with gauzy veils. The men were no less flamboyant, sporting richly brocaded doublets with high, fluted collars and exotically draped hats and teetering on jewel-encrusted shoes with high red heels and spring-curled toes.

In the van of the procession strolled the most magnificent pair of all, locked in animated conversation. I had never seen her at close quarters, but I knew instantly that this must be the queen, linked arm in arm with her brother-in-law the Duke of Orleans.

Queen Isabeau was not slender any more – eleven children and all those succulent roasts had seen to that – but on this stifling afternoon when everything was melting, she glittered like ice. Her gown was of lustrous pale-blue silk so liberally woven through with gold thread that it shimmered as she moved and around her shoulders hung thick chains of pearls and sapphires. On her head an enormous wheel of pale, iridescent feathers was pinned with a diamond the size of a duck’s egg.

Her escort was no less resplendent. Louis of Orleans was tall and handsome with a jutting jaw, a long, imperial nose and twinkling speckled grey eyes. To my astonishment there were porcupines embroidered in gold thread and jet beads all over his gown and his extravagantly dagged hat was trimmed with striped porcupine quills, which rattled as he walked. It was only later that I learned that the porcupine was the duke’s personal emblem. Louis of Orleans liked everyone to know who he was.

I was so mesmerised by these visions of fashionable extravagance that I had forgotten to scamper out of sight and now I could only sink to my knees, for Catherine and Charles had taken shelter behind me and were clinging to my skirt. As it turned out I need not have worried, for I do not think Queen Isabeau even noticed us. She only tore her gaze from the duke in order to fix it on Michele, who was now standing nervously, clutching her book like a shield.

‘Princesse Michele?’ The queen beckoned to the trembling girl and I detected a distinctly peevish note in the deep, Germanic voice. ‘It is Michele, is it not?’

Well may she ask! I heard my own voice exclaim inside my head. To my knowledge she had not laid eyes on this daughter of hers more than once or twice in the nine years since her birth.

‘Come. Come closer, child!’ She made an impatient gesture.

The grubby hem of Michele’s skirt moved into the scope of my vision and I saw her bend her knee before her mother. For one so young her composure was remarkable.

‘Yes, you must be Michele. You have my eyes. And these are your brothers, are they not?’ She gestured towards Louis and Jean and nodded at Michele’s whispered, ‘Yes, Madame.’

‘Of course they are! What other children would be playing in Queen Jeanne’s garden? But how wretched you look!’ exclaimed the queen. ‘Have you no comb – no veil? And your gown … it is dirty and so tight! Where is your governess? How dare she allow you to be seen like this?’

Michele coloured violently, her expression a mixture of fear and shame. I waited to hear her denounce Madame la Bonne but she merely swallowed hard and shook her head. Perhaps she knew that her all-powerful mother would never believe the truth; that the nursery comb had few remaining teeth, there were no clean clothes and the governess was closeted in her tower chamber counting the coins she had managed not to spend on her royal charges.

‘Have you forgotten your manners?’ the queen demanded. For a tense moment it looked as if she might explode into anger but then she shrugged and turned to the duke. ‘Well, never mind. Young girls are better quiet. What do you think, my lord? Will she polish up for your son? He is only a boy after all. They are cygnets who can grow into swans together!’

Louis of Orleans bent and placed one gloved finger under Michele’s chin. The little girl’s eyes grew round with apprehension, giving her the appeal of a frightened kitten. The duke smiled, releasing her. ‘As she is your daughter, Madame, how could she be anything but perfect? I love her already and so will my son.’

The queen laughed. ‘You flatter us, my lord!’ Orleans’ charm made her forget Michele’s shortcomings and the absent governess. She waved the large painted fan she carried. ‘Michele, Louis, Jean, follow me. I am glad to have found you in the garden. It has saved us sending men to search the palace. The time has come for you to leave here. It is no longer safe for you. The new Duke of Burgundy thinks he can use you to rule France himself but I am your mother and the queen and I have other plans. You need bring nothing. We are leaving now.’

Her words fell like a thunderbolt in the scented garden. The three named children exchanged astonished glances; Michele with alarm, Louis with excitement and Jean with bemusement. None of them dared to speak.

‘We are going somewhere where Burgundy cannot force you into undesirable alliances. We will foil his schemes and you will have new playmates in your uncle of Orleans’ children. Ladies!’

The queen snapped her fan at her attendants, two of whom hastened forward to manoeuvre the long train and voluminous skirt around her feet so that she could turn around. While they busied themselves, she cast another doubtful glance at her children, then leaned closer to Orleans, murmuring, ‘Are they worth saving from Burgundy’s machinations? They look a sorry bunch to me.’

Orleans made a reassuring gesture. ‘Have no fear, Madame, they are of the blood royal. They will polish up.’ He turned to address Michele, who still clutched her book fiercely, as the only solid object in a violently shifting world. ‘The Duke of Burgundy wants to marry you to his son, Mademoiselle, but how would you like to marry my son instead?’

He clearly expected no reply, for the procession was already moving off, back towards the river-gate, and he immediately returned his attention to the queen, missing Michele’s eloquent glance in my direction. ‘I told you so,’ it said, ‘I am to be married to heaven-knows-whom and taken to heaven-knows-where!’ I crossed myself and whispered a prayer for her. Poor little princess, her worst fears were realised.

‘But the dauphin is our first priority,’ the queen insisted more forcefully, still within earshot. I saw little Louis flush at hearing himself referred to by the title he had so long desired. ‘If he can marry Louis to his daughter, Burgundy will try to rule through him.’

‘You are right, as always, Madame,’ acknowledged the duke. ‘The dauphin, most of all, must be kept away from Cousin Jean. He who calls himself Fearless! What is fearless about stealing children? Jean the Fearless – hah!’ The porcupine quills rattled their scorn as the Duke of Orleans tossed his head and cried, ‘But you need have no fear, my children! He shall not steal you from your mother. Forward! We are heading for Chartres, with all speed.’

These were the last words I heard because the two remaining infants began to jump and wail beside me as their siblings walked away without a backward glance. Who could blame them? They were confused and frightened. A band of total strangers had invaded their world and within minutes their sister and brothers were disappearing. The river-gate clanged shut. A band of musicians on the galley struck up a merry tune as if nothing untoward had occurred. Sailing off in her cushioned galley, Queen Isabeau was totally unaware of the misery she left behind.

Nor were the day’s dramas over. I had taken Catherine and Charles to the seat in the overgrown arbour for a reassuring cuddle, so I did not see a group of men arrive at the palace end of the garden and begin to play some sort of game in the bushes, but the unusual sound of excited whoops and male laughter soon reached us and I popped my head around the sheltering foliage in alarm. We had always had the garden to ourselves and I had no wish to encounter any fun-seeking courtiers or playful lovers who might have strayed there. I wondered if we could escape to the nursery tower without being seen.

Alas, we could not. The strange and disturbing figure of a man was already approaching our hiding-place and had seen me poke my head out. He stopped dead with a smile of childish glee frozen for an instant on his thin, pale face before it turned to a ghoulish grimace of dismay. Strangely, in this palace of smooth-cheeked, neatly-trimmed courtiers, his chin had a growth of straggly brown beard and his lank hair trailed down in a messy tangle to his shoulders. His clothing was rumpled and filthy, but had once been fine and fashionable, the shabby blue doublet edged with matted fur and patterned with a tarnished gold design that might once have been fleur-de-lis. With a fearful flash of intuition I realised that I was now, incredibly, face to face with the ailing king, as if having just encountered the queen were not enough for one day, not to mention having lost three of my charges.

We stood speechless with shock at the sight of each other, but Catherine, whose curiosity never dimmed, stepped past me into the king’s path. As she did so, two sturdy men in leather jackets appeared at the far end of the garden – the king’s minders. I reached to pull Catherine back, but she wriggled out of my grasp and walked boldly up to the stranger, staring at him enquiringly. ‘Good day, Monsieur. Are you playing a game?’ she asked sweetly. ‘May I play too?’

She did not know, of course, that this might be her father. She had never met him, any more than she had met her mother, and a three year old who is not shy will always be ready to play with someone new, oblivious of circumstances.