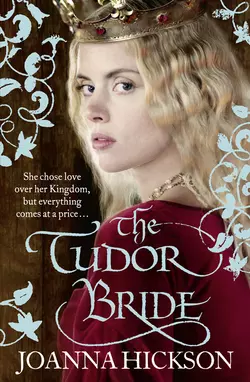

The Tudor Bride

Joanna Hickson

The thrilling story of the French princess who became an English queen, from the best-selling author of The Agincourt Bride. Perfect for fans of The White Queen.Even the greatest of queens have rules – to break them would cost her dearly…King Henry V’s new French Queen, Catherine, dazzles the crowds in England but life at court is full of intrigue and her loyal companion, Mette, suspects that the beautiful Eleanor Cobham, protégée of the Duke of Gloucester, is spying for him.Catherine believes herself invincible as she gives birth to an heir, then tragically King Henry is struck down by fever. Unable to outwit those who seek to remove the new king from her care, Catherine retires from court, comforted by the King’s Harper, Owen Tudor.At the secluded manor of Hadham a smouldering ember bursts into flame and Catherine and Owen Tudor become lovers. But their love cannot remain a secret forever, and when a grab for power is made by Gloucester, Catherine – and those dearest to her – face mortal danger…

JOANNA HICKSON

The Tudor Bride

Copyright (#ulink_70ab0478-7a69-53e5-b2d1-43b6c4ba5592)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2014

Copyright © Joanna Hickson 2014

Cover photographs © Richard Jenkins (main image); Shutterstock.com (http://www.Shutterstock.com) (patterns). Cover lettering © Stephen Raw

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2013

Joanna Hickson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007446995

Ebook Edition © January 2014 ISBN: 9780007564637

Version: 2017-07-12

For Katie and young Hugo

who are my Catherine and young King Henry.

Contents

Cover (#u3c52bc03-8bd9-5545-baf3-7a8f691834a6)

Title Page (#uac69337b-fa03-5fbb-961b-8b1eb3cd3665)

Copyright (#u06939ef9-7b0b-5245-8c58-d310d0717518)

Dedication (#ued4b8759-917b-5cb1-8741-2e8f44d18608)

Family Trees (#ue5d5ffb7-3656-5627-9303-fa4d852e17c1)

Map (#u2e8d521a-0087-51a9-a3db-a44cd4a35a11)

Narrator’s Note (#ufbc6d721-ef92-5291-a1ee-c8cbd5a78876)

Part One: Queen of England (1421–1422) (#ub0173ebb-1fdb-5314-8c2c-f33476116494)

Chapter 1 (#u354d5407-185a-5119-9d7d-fe6fdd39d08a)

Chapter 2 (#u6c278bd5-39c4-5af2-8fd4-de3b9c15a9d8)

Chapter 3 (#u5014b15b-6b4d-5908-abed-69b2d7a33da8)

Chapter 4 (#u52b855da-e6b0-56c4-abce-9e949ac8f721)

Chapter 5 (#ua4c71396-0a1a-590e-be67-07573afbd7e6)

Chapter 6 (#u7434bbea-449d-580d-b3d8-0195ce64a8c5)

Chapter 7 (#u6920b810-c30b-5db7-9d6d-00d05dbc2a35)

Chapter 8 (#u61a76c00-1ad7-546a-b07e-6d841a86b1ab)

Chapter 9 (#ud27c0bfc-39b4-5503-bee4-afebc666d4ff)

Chapter 10 (#u04ba9909-1b8f-5d6f-9a68-3dc8d722d52b)

Chapter 11 (#u901f2e66-af30-540a-95f2-c6c229a2d2be)

Chapter 12 (#ud4ed06b0-a01d-5e5c-9e9a-33c76def830d)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two: The Secret Years (1427–1435) (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three: Journey into Jeopardy (1435–1437) (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 44 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 45 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 46 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 47 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 48 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 49 (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note: Fact and Fiction (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By the same author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

NARRATOR’S NOTE (#ulink_29cc7c1f-1cc3-57ad-991c-9820062e93a9)

The House of the Vine, London, Summer 1440

Respected Reader,

My name is Guillaumette, known to my friends as Mette. Some of you may already know that and yes, I am French but I write this at my house in London, where I live very quietly now. You will understand that the French are not much liked in England today, so I think it best to speak and write in English.

It is not my own story I write; this is the story of my mistress, Catherine de Valois, youngest daughter of the French king Charles the Sixth, whom I suckled as a baby, nursed as a child and tried to console through the troubled years of her girlhood, during which she was offered by various of her male relatives to the invading enemy, King Henry the Fifth of England, as his bride. This she eventually became, not entirely without her consent, in June 1420. By the end of that year, as a result of his extraordinary military success, an alliance with the Duke of Burgundy and a very favourable (to him) peace treaty, King Henry and his new bride were able to enter Paris in triumph, he as the new Regent and Heir of France and she as his queen. Afterwards they sailed for England as a golden royal couple, ready to be féted and celebrated, not least at Catherine’s coronation in London. And I sailed with them.

Since France lay devastated by years of constant warfare, you may think it was a relief for me to follow in the new queen’s train, but I left France with a heavy heart. I had always been close to my daughter Alys, who with her husband and baby girl lived in Paris, which was now under English rule. My son Luc, meanwhile, had sworn his allegiance to Catherine’s seventeen-year-old brother Charles, the former Dauphin, who had been disinherited and declared illegitimate by his sister’s marriage treaty and forced to retreat to his loyal territories south of the Loire. Charles would have to fight the combined armies of England and Burgundy if he was to win back his name and his claim to the French throne. Catherine and the Dauphin’s father, King Charles, was subject to devilish fits and often confined to a padded room, believing he was made of glass and terrified of being shattered; a living metaphor for the shattered state of his kingdom and, I fear, the splintered state of my family. Regrettably we were typical of French people at the time, the divided victims of violence and political upheaval. I did not depart with a light heart.

Nevertheless, when we embarked at Calais, part of me was glad to be leaving the chaos behind but, I realise now, twenty years later, how little notion I had of what we were sailing into. Catherine had no choice, she was by law the Queen of England, whether the English liked her or not; but for me it was different. I followed her out of loyalty and love, but there were times later, I assure you, when I wondered whether I had done the right thing in boarding that ship …

PART ONE (#ulink_dab15a23-2bb6-550a-a21d-4768d35bb356)

1 (#ulink_5befc063-8178-52d9-bd4d-3a131f290234)

The grey-green sea looked hungry as it lapped and chewed on the English shore, voracious, like the monsters mapmakers paint at the edge of the world. With her sails flapping, the Trinity Royal idled nose to the wind under the walls of Dover Castle, a vast stronghold sprawled atop high chalk cliffs which gleamed in the flat winter sunlight. Visible against this great white wall were the flags and banners of an official welcoming party and a large crowd of onlookers gathered along the beach. Unfamiliar music from an unseen band drifted past us on a dying breeze.

Having almost completed my first sea voyage, I could not say that I was an enthusiastic sailor. I felt salt-stained and wind-blown, my only consolation being that the sea-swell which had plagued my stomach all the way from France had now eased and the ship’s movement had dwindled to a gentle rocking motion. Queen Catherine, by contrast, looked radiant and unruffled after the crossing, even when faced with the prospect of being carried ashore in a chair by a bunch of braggart barons, bizarrely known as the Wardens of the Cinq Ports; bizarrely because there were seven towns involved, not five as the title suggested, and some of them were not even ports. Apparently this chair-lift was an English tradition, but personally I considered it barbaric that a king and queen should be expected to risk their lives being carried shoulder high over treacherous waters to a stony beach when they could have made a dignified arrival walking down a gangway onto the Dover dockside. Besides, as Keeper of the Queen’s Robes, I, Guillaumette Lanière, was the one who would have to restore the costly fur and fabric of the queen’s garments from the ravages of sand and salt-water.

King Henry discussed this singular English honour with his brother, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, when the duke boarded the Trinity Royal from his galley, half a league off the white cliffs. That his grace of Gloucester thought himself a fine fellow was amply evident in the swashbuckling way he climbed the rope-ladder, vaulted the ship’s rail one-handed and sprang up the stair to the aftcastle deck, where the king and Queen Catherine stood waiting. Gloucester sported thigh-high polished leather boots and his short green doublet clung tightly to his muscular physique, admirably displaying the heavy gold collar and trencher-sized medallion of office which hung around his broad shoulders. His bend of the knee was practised and perfect, accompanied by a flourish of his right hand as he grasped his brother’s with the left.

‘A hearty welcome to both your graces!’ He pressed his lips to the king’s ring, but raised his eyes not to his brother’s face but to Catherine’s. ‘England waits with bated breath to greet its beautiful French queen.’

A faint flush stained Catherine’s cheeks, but she remained straight-faced under the impact of Gloucester’s dazzling smile. If the duke’s youth had been in any way misspent, it did not show. I believe few men of thirty could boast such a fine, full set of white teeth as that smile revealed. His face was clean-shaven, smooth and unblemished, in striking contrast with the scarred and care-lined visage of the king, only five years his senior.

‘We hear you have a ceremonial welcome planned for us, brother.’ King Henry raised a quizzical eyebrow. ‘We are to be carried shoulder high through the surf.’

Gloucester appeared reluctant to drag his gaze from Catherine’s face. ‘Indeed, sire, as is customary for people of great rank and honour. You will be pleased to hear that the surf has dwindled to friendly ripples now though. You may remember that we welcomed Emperor Sigismund to these shores with the Wardens’ lift. We can do no less to honour the return of the glorious and victorious King of England and France – and the advent of his beauteous queen – than was appropriate for a visiting Holy Roman Emperor.’

King Henry frowned. ‘It is ill-judged, Humphrey, to place the crown of France on my head while the father of my queen still lives.’ He made an irritable upward movement with his hand. ‘But rise, brother, if only to explain how we are to enter these chairs of yours without getting wet. As you know, I have always avoided such mummery in the past.’

When he rose, Gloucester stood almost as tall as the king and a head taller than Catherine. ‘A simple matter, sire!’ he declared, gesturing over the side of the ship. ‘The litters are fastened ready, there on my galley. The captain will bring the ship as near to the shore as he may, the gangway will be lowered onto the galley and you and Madame, the queen, will walk regally down it. Once safely seated, you will be rowed towards the shore until the water is shallow enough for your Wardens to wade in, take the litters on their shoulders and bear them ceremoniously up the beach. The trumpets will sound, the musicians will play and the crowds will cheer. When he can make himself heard, the Lord Warden – my humble self – will make a speech of welcome, then your litters will be lifted shoulder high once more for the short journey to the castle.’

‘And do I have your solemn word that there is no question of either of us receiving a ducking?’ The king favoured his brother with a fiercely narrowed gaze.

Gloucester made an appreciative gesture in Catherine’s direction. ‘Her grace appears to be made of fairy dust, my lord. I would wager we could carry her from Dover to London without effort. As for your grace’s royal person, it can surely rely on divine protection to remain dry.’

‘Hmm.’ King Henry grunted non-committally.

Catherine suddenly favoured Gloucester with one of her most regal smiles and surprised him by speaking in charming broken English, her voice light but firm. ‘My lord of Gloucester is gracious to honour us with this ceremony, but should I not also descend from the chair and set my foot on English soil?’ She turned to the king. ‘Perhaps we could walk to the castle, my lord? It does not look far. The people will the better have a sight of us.’

King Henry shot a sharp glance at his brother, who shook his head almost imperceptibly and said hastily, ‘That might be unwise, Madame. It is a steep climb. But Madame will have the opportunity to set foot on English soil when she reaches the town gate. There, the mayor of Dover waits to present you with the freedom of the town. I can assure you that the populace is out to greet you. Walking anywhere would render your graces susceptible to the attentions of over-eager citizens in the narrow streets, and besides we go in procession to the castle. Teams of hand-picked burghers are waiting to shoulder your chairs, and I think when you witness the exuberance of our English crowds you will understand the need for being raised above the common herd. Also, I trust you will forgive the coarseness of the people’s greetings. They will doubtless shout “Fair Kate!” as you pass. It is not meant to offend, but to please. Fair is in praise of your beauty and Kate is a shortening of your name.’

‘The king has told me this. If they think me fair before they have properly seen me, such blind devotion cannot be deemed … how do you say? … an insult,’ responded Catherine with a smile. ‘And if they call me fair, how can I then not like the name they give me?’

I watched Gloucester bow deeply to Catherine and thought I saw a spark of recognition in his eyes, as if he realised that, like him, she possessed a keen appreciation of the importance of public acclaim. ‘You are a lady of great wisdom, Madame. And you are to be congratulated on your grasp of English. Is she not, brother?’

King Henry directed one of his rare smiles at Catherine. ‘You will find that my queen grasps many things quickly, Humphrey, including the strategic value of flattery. Now, let us get this adventurous journey started. I think you will need help in mounting the chair-litter, Catherine, however much my brother makes light of the matter! You should summon your attendants.’

There were only three of us to summon because all but one of Catherine’s French ladies-in-waiting had been left with their families in France. The exception was the devout and practical Agnes de Blagny, a knight’s daughter who had been orphaned and impoverished by her father’s death at the Battle of Agincourt. She had come to the French court with Catherine from their convent school, where they had been close friends. The other attendant was a young English beauty, Joan Beaufort, daughter of the Duchess of Clarence and step-daughter of King Henry’s brother Thomas, Duke of Clarence. The duchess was also accompanying Catherine to England to instruct her in the protocol of the English court. At nineteen and fourteen years old respectively, my two colleagues in attendance on the new queen were better suited, I willingly admitted, to help Catherine down the gangway and onto the gilded chair-litter that was roped tightly to the bobbing galley. Being the same age as the English king, I am not suggesting I was over the hill in any way, but I confess that my thirty-four years had broadened my beam and made me less agile than my younger companions. However, I think I can safely say that my relationship with Queen Catherine ran closer and deeper than that of any teenage court damsel, for I had suckled her as a babe, nursed her as an infant and steered her through a profoundly troubled girlhood. She had left her mother, Queen Isabeau, in Paris without a second thought, but in order to bring me with her to England she had raised me from the rank of menial servant and given me a courtier’s post as one of her closest confidantes. I had journeyed a long way from my father’s bakery on the banks of the Seine.

I bustled behind Agnes and Joan, directing proceedings as they did all the bending and tugging, easing the queen’s voluminous skirts down the narrow gangway. The king and the duke handed her into the galley and the girls helped her into the litter, tucking the folds of her costly gown around her feet to keep it clear of the water.

As the galley drew nearer to the beach, seven men wearing short doublets and thigh-high bottins started to wade out towards us, the wavelets lapping first at their leather-clad ankles and then rising up their shins. The shingle shelved very gradually and they were a good thirty yards offshore before we came alongside them, at which point the Duke of Gloucester stood up and leaped casually over the side, landing up to his thighs and causing a mighty splash. Muttering under my breath, I hastily brushed the water drops from Catherine’s fine worsted skirts as the rowers shipped their oars and those nearest to the chair-litters began to untie the ropes attaching them to the galley.

‘Have no fear, my beautiful queen,’ Gloucester said as the galley rocked turbulently, unbalanced by the rowers’ efforts to heave Catherine’s litter over the side and onto the shoulders of the bearers. ‘Archbishop Chichele was our last carry and he is twice your weight.’ He glanced over his shoulder at the other three men in his team and signalled with his free arm. ‘Forward, fellow wardens!’

As they began moving, I saw Catherine raise her chin, summon a fixed smile and lift one hand to wave to the crowd. On the other side of the galley, King Henry was already shore-bound.

The rowers returned to their oars and the galley began to swing away towards the jetty, giving me a clear view as the Duke of Gloucester suddenly sank up to his chest and the queen’s chair tilted violently.

I cried out in alarm and the cheers from the onlookers instantly turned to a collective gasp of horror as Catherine lurched forward in her seat, clinging desperately with the one hand that was still clutching the arm of the chair. The duke appeared to struggle to regain his balance, but just as it seemed Catherine must topple forward into the water, he thrust his arm upwards to return the litter to the horizontal and throw her back into the chair. There was no particular reason to think that his stumble had been deliberate, but I could not help wondering. Although he was soaked to the armpits, he did not look greatly troubled when he turned to speak to her and I had the chance to see his face.

‘A thousand pardons, my queen. A loose stone attempted to trip me, but as you see it failed. All is well and your adoring public awaits.’

The galley moved out of earshot before I could catch Catherine’s reply, but I recognised her expression. It was one of anger and suspicion, as if she too doubted Gloucester’s integrity, but it lasted only moments, then her smile returned, growing ever more confident as the cheers of the crowd redoubled. I cast a glance at King Henry to gauge his reaction to the incident, but he was looking the other way and had not seen it.

Marshalled behind stave-wielding sergeants, the people surged forward on the shingle waving evergreen branches and coloured banners and hailing their hero king and his trophy French queen.

‘God bless Queen Kate!’ Fair Kate! ‘Bonny queen!’ ‘Hail to the conquering king!’ ‘God bless good King Hal!’

From this moment of her arrival on the Kent coast, there was the same noisy tumult wherever she went. Gloucester had been right in every particular about the people being rowdy, but I was unprepared, even so, for the triumphant mood of the crowd as we passed through the steep streets of Dover in procession to the castle.

This scene was repeated on following days, time and time again, as the royal train made its slow progress towards London. At every village the populace turned out in their best clothes, precious relics and religious banners were paraded out of the churches and petitioners scrambled to catch the king’s attention or beg the queen’s blessing for their children. Even the weather showed favour, bestowing on the royal procession unseasonal warmth, bright sunshine and blue skies. Despite winter-bare trees and sparse vegetation, the countryside looked fertile and well-farmed, in sharp contrast to the abandoned and unkempt fields of Normandy, from where we had recently come.

It was during our three-week stay in Rouen, before we took ship for England, that Catherine had insisted I take riding lessons. As a baker’s daughter from the back streets of Paris, I had never learned to ride and, until I began to travel around France with the court, I had never seen the need. Even though I had been married at fifteen to a groom in the royal stables, apart from our frequent and lusty use of the hayloft above their stalls, I had never had much truck with horses until Catherine decided it was time I did. I had rapidly discovered that now she was a queen, when she made a decision something was done about it.

‘You cannot accompany me on a royal progress if you have to ride on one of the baggage carts, Mette,’ she had complained. ‘I may need you en route and will not want to wait while someone goes to search for you at the back of the procession. Besides, I assure you that it is much more comfortable to ride a horse than to be bounced around on a cart.’

One of King Henry’s grooms had been instructed to find a docile cob and teach me the rudiments of horsemanship. It did not take long, for all I needed to do was walk and trot and keep my mount safely reined in behind the horse in front. I was not intending to chase after the hunt or indulge in adventurous gallops across moor and heath. What I had not anticipated, however, were the aches and pains that resulted from sitting on a horse for long periods of time.

However, my legs and rump grew accustomed to it and by the time we reached Canterbury, I had become quite comfortable in my sideways saddle, and grown fond of the sturdy brown mare which had been procured for me at Dover, reared and broken I was told, on the wild moors of England’s south-west. She had been named Jennet, but I decided to re-christen her Genevieve after the patron saint of Paris and hoped she would look after me just as that virgin saint protected my home city.

But my poor mare had begun to limp by the time we arrived at the abbey of St Augustine in Canterbury, where the royal household was to lodge while visiting the city and the tomb of St Thomas à Becket. That evening the king and queen were dining privately with the abbot and I took the opportunity to slip away and check whether any of the grooms had tended my horse’s front foot. But when I led her from her stall, I found that she was still lame. Dusk was falling and I had no idea what to do, so I began searching about for some assistance. To my surprise, the only person I encountered was little Joan Beaufort, looking flustered and nervous and very out of place in her elaborate court dress and furred mantle.

‘Sweet Marie, Lady Joan, a young girl like you should not be wandering about the stables alone at this time. What are you doing here?’ Apart from being the epitome of English beauty – strawberry-blonde, blue-eyed and apple-blossom-cheeked – as the king’s cousin and step-niece, Joan was one of the most eligible damsels of the court.

‘Searching for you,’ she replied, obviously very relieved to have found me. ‘I have been looking everywhere.’

‘My horse is lame,’ I said. ‘I want someone to tend her foot.’

An eager look animated the court beauty’s face. ‘I know about horses. I always preferred the stables over needlework. Has the mare got a stone in her hoof?’

I shook my head. ‘I have no idea. How do you tell?’

‘Let me take a look. Is that her over there?’ She trudged off to where I had tied Genevieve back in her stall a few yards away, ignoring the horse dung and wet straw which mired her slippers and sullied the hem of her priceless brocade gown. Giving the mare a gentle pat, she bent down and expertly lifted her front hoof, peering at its underside. ‘Yes, there is a stone in this one.’ She placed the foot carefully down and turned to me. ‘I need something to prise it out with. A strong stick would do.’

I was about to go off in search of an implement when I suddenly realised that she must have been seeking me for a reason. ‘Incidentally, Lady Joan, why were you looking for me?’ I asked.

She frowned. ‘Oh, I almost forgot. The queen wants you. She is in a frenzy.’

2 (#ulink_02fa0bde-6917-504b-bb5e-e6ccaa390a58)

If Catherine had ever been in a frenzy it had abated by the time I got to her, but she was certainly angry, pacing around the grand bedchamber in the abbot’s house, which he had vacated in favour of his royal guests.

‘Where on earth have you been, Mette? I wanted you and you were not here.’ There was a strident, peevish note in her voice that was new to me. She could be cross and critical at times, but was not usually given to petulance.

‘I am sorry, Mademoiselle. I went to the stables to check on Genevieve.’ It was hardly a grovelling apology, but I soon realised that perhaps it should have been.

‘Do you mean to say that you abandoned your queen in favour of a horse?’ she almost snorted. ‘Is there something wrong with your horse?’ The sharp tone of this enquiry did not imply any sudden burst of equine benevolence on her part.

‘She had a stone in her hoof,’ I replied. ‘Lady Joan removed it for me.’

This revelation brought her anger fizzing to the surface again. ‘This is unbelievable! I have three ladies to serve me and yet when I need their assistance I find that two of them are dancing attendance on a horse!’

Wondering what it was that could have brought on this uncharacteristic fit of pique, I decided that there was nothing for it but to act the truly humble servant. ‘Forgive me, your grace,’ I said, abandoning my usual, more familiar, form of address. ‘I had no idea you were in such urgent need of me. How may I serve you?’

She turned her back and paced away across the room. ‘Oh it does not matter now. Clearly my problems are of no consequence compared to a stone in your horse’s hoof!’

Agnes de Blagny, who had borne the brunt of the queen’s initial outburst, was making faces at me behind Catherine’s back. I found her facial gymnastics hard to interpret, but gathered it had involved King Henry in some way.

‘Please, Madame – your grace – tell me what it is that has upset you. Does it concern the king? Was it something he said?’

She swung round at that, her eyes suddenly brimming with tears. ‘All day people have been calling out my name, begging for my glance, holding out their children for my touch. I am their beautiful queen, their Fair Kate, their Agincourt Bride. But my husband, the one who should have my glances and my touch and whose child I should be bearing, prefers to squander his attention on debating Christian doctrine with the abbot and inspecting the abbey’s library of dusty old books. And tomorrow, after he has prayed for an heir at the tomb of St Thomas à Becket, he says he must leave me here and hasten to Westminster to meet with his counsellors. I ask you – where in all the two thousand books the abbot is so proud to display to the king does it say that there has ever been more than one Immaculate Conception? What is the use of praying for an heir if Henry does nothing about actually getting one?’

There was the crux of the matter. She might be the darling of the crowds but, deep down, she would be an inadequate failure as a queen if she did not produce the heir that was so essential to securing the future of the crowns of England and France. Her marriage to King Henry was the very embodiment of the unification of the two kingdoms. She was the living proof of his remarkable conquest of more than half of France, but the joining of the two crowns, set in law by the Treaty of Troyes at their wedding eight months before, would be useless unless there was a male child born of the marriage; an heir to inherit the empire King Henry was creating and to carry it through to succeeding generations. On the surface Catherine was the ultra-beautiful, super-confident Queen of England and presumptive Queen of France, but inside she was a quivering mass of insecurities, all centred on the imperative conception of that child.

I hurried across the room to the abbot’s carved armchair into which she had sunk with a heavy sigh. ‘His grace will be here soon, Mademoiselle, I am sure,’ I said, lapsing back into the intimate form of address I had used ever since we had been reunited when she came to the French court at thirteen, fresh from her convent school. To me she would always be ‘Mademoiselle’, however many grand titles she acquired. ‘He rarely fails to wish you goodnight, even if he works into the small hours.’

Catherine gave me a withering look, far from mollified by my attempt at consolation. ‘A goodnight kiss is hardly going to sire the next king of England, Mette,’ she complained, fretfully tugging at the pins that secured her veil to her headdress. ‘Henry could learn something from his subjects when it comes to enthusiastic outpourings of love!’

I gazed at her ruefully. What she was trying to tell me was that King Henry had not performed his duty in the marital bed for some time and I was guiltily aware that I might be partly responsible for this lack. A month ago, just after Epiphany, Catherine had miscarried. It had not been a well-developed pregnancy, but for a few joyous weeks she and Henry had believed the essential heir had been growing in her womb. Fortunately they had not made any announcement to this effect, having followed my suggestion that it might be best to wait until a few more weeks had passed; so Catherine had not had to suffer court murmurings of dissatisfaction and doubt about her ability to bear a child. But of course it had been a bitter disappointment for the king and queen. To my surprise, the king had not been critical of Catherine or blamed any lack of care on the part of her attendants, including myself, which had emboldened me to advise him that it would be wise to allow her a few weeks to recover before making any further attempt to get her with child. The fact that I had not told her of this conversation was now coming home to haunt me. The king might be scrupulously following my advice, but the queen was misinterpreting his restraint, construing it as lack of interest.

I decided to try a fresh approach. ‘I recall the king saying he was eager that you should be crowned his true consort before any heir was born, Mademoiselle. Perhaps he has decided that it would be best even to delay conception until after your coronation, believing that God will bless your union once you are both consecrated.’

The feverish removal of hair-pins ceased suddenly. Catherine now turned to meet my gaze, which she had so far avoided, a flicker of hope dawning. ‘Do you think that could be so, Mette? Really?’

I nodded vigorously, glad to have provided at least some crumb of comfort. ‘Yes, Mademoiselle. As you know, the king lays great stress on divine approval of his actions. Truly I believe you should not doubt his regard for you or his trust in God’s holy will.’

She frowned. ‘But if he is convinced that it is God’s will anyway, why has he sworn to pray for a son at the shrine of every English saint we pass in our progress through the kingdom?’

I gave her a mischievous smile. ‘Why do you attend Mass every day, Mademoiselle, when God must know that you worship Him unreservedly anyway? Is it not to demonstrate your faith to the world?’

Catherine’s brow wrinkled as she considered this. ‘Actually, I think it is to reinforce my faith, Mette,’ she said after a moment.

‘Well then, perhaps the king is reinforcing his faith in God’s will by giving Him a little reminder now and then,’ I responded.

She gave me a reproachful look. ‘I have said it before, Mette, you are too flippant in your attitude to God and the Church.’ However she spoke more calmly having revealed what was the immediate cause of her outburst. ‘Tomorrow the king will be leaving us and going on ahead to London to supervise arrangements for my coronation,’ she informed us. ‘The date has been set for February the twenty-third. That is just over a fortnight away.’

‘And what will you do in the meanwhile, Mademoiselle?’ I asked, seeking to glean some idea of when and where we were to make our own arrangements for this momentous event.

‘We are to travel to Eltham Palace, which is apparently a royal palace close to London, where we can rest and organise ourselves for the big day.’ Catherine turned to young Joan, who had been hovering quietly nearby waiting to assist her to undress. ‘You may help me to choose my maids of honour for the ceremony, Joan. I am told that a number of young ladies are to present themselves at Eltham Palace for my consideration and I believe three of them share your name, or a version of it. It seems that in future I may call “Joan!” and four of you will answer.’

Young Joan Beaufort lifted her chin proudly. ‘But I was here first, Madame. The others will have to take different names.’

I was delighted to hear Catherine’s laugh ring out and see a twinkle return to her eye. ‘You are right, little one! You shall be the one and only Joan and we will call the others something else. Meanwhile, please come now and help me take off this headdress.’

Joan advanced to pick up the discarded veil and remove the jewelled net and fillet which had restrained Catherine’s pale gold hair for her dinner with the abbot. Agnes and I exchanged relieved glances; a crisis had erupted and now seemed to have subsided, but I did not doubt there would be many more over the next weeks and months. This had been a warning that for the foreseeable future we would have to deal with a vulnerable young queen whose growing popularity would doubtless continue to wreak its share of havoc with her mood, causing her to veer alarmingly between intense self-belief and a desperate sense of inadequacy, unless and until her confidence was bolstered by the arrival of a viable male child. King Henry would not be the only one praying for an heir at the shrines of the English saints. Very likely I would be creeping in behind him with my own fervent prayers of intercession.

3 (#ulink_33784efd-2ca9-522d-987e-f453ee63aaba)

Our first sight of Eltham Palace was a disappointment to those of us who measured English palaces against the sprawling, marbled splendour of the French king’s Hôtel de St Pol in Paris. Eltham had once been a royal hunting lodge and the densely wooded park around it was certainly extensive, but the demesne itself had been developed in a higgledy-piggledy fashion with a variety of accommodation towers and half-timbered guest houses strung out around the walled bailey, cheek-by-jowl with the kitchens, dairies and breweries, not to mention rows of lean-to wooden stables, kennels and mews, with all their attendant muck and stink. Situated above all this, on a raised mound, were the royal apartments, great hall and chapel which, although built of beautiful mellow stone and modernised with elegant oriel windows, looked surprisingly inadequate for a palace where King Henry’s father was reported to have lavishly entertained the Byzantine Emperor twenty years before. However, as we rode up to the gatehouse, I noticed a vast tourney ground laid out beyond the curtain wall and concluded that the entertainment on that grand occasion must have been chiefly al fresco.

My information about Eltham had been provided by a pleasant and unassuming young man called Walter Vintner who joined us during the later stages of our journey. To my surprise he did not seem averse to riding alongside an older, wimpled member of the queen’s entourage. As we rode out of Rochester that morning, I had smiled at him, thinking what a personable youth he was, polite, fresh-faced and soberly attired in riding hose and boots, a short dark-brown doublet and cloak and a cheerful green hat with a feather in it. A clue to his employment was an ink-horn which he wore slung from his belt alongside a leather scrip, which I quickly learned contained the quills and paper he needed as one of the clerks of the king’s household.

After we had discovered each other’s positions within the royal retinue, I took the bold step of pursuing him with flattery. ‘You are so kind to speak French with me, Master Vintner, and with such clarity that I am prompted to pick your brains rather than those of your fellow countrymen who speak with accents I am afraid I find difficult to understand.’

‘Ah, you have my father to thank for that,’ he confided. ‘He is so often in France on the king’s business that he speaks the language like a Parisian and has teased me into doing the same.’

‘Royal service is a family tradition, then,’ I remarked. ‘Is your father also in the king’s employ?’

‘Indirectly,’ he replied. ‘He is a lawyer at the Court of Common Pleas in London, but the royal council has need of his advice on diplomatic missions to Rouen and Paris. I do not ask what these missions are, nor do I think he would tell me if I did.’

My eyebrows probably disappeared under the band of my coif. ‘Is your father a spy then, Master Vintner?’

He laughed. ‘No, Madame! He deals with confidential legal negotiations between the English and French administrations. In truth I know no more than that. And please, why do you not call me Walter? I am not yet used to being addressed as “Master”.’

‘Why, how old are you … W-walter?’ I stumbled over the very English way he said his name, pronouncing the W as I remembered Catherine’s younger brother Charles had mispronounced his Rs when he was an infant in the nursery, and Catherine was his adored playmate; the same brother who now called her traitor for marrying his country’s conqueror.

‘I am nineteen. Although my father thinks I behave more like a twelve year old.’

I was struck by the sudden thought that he was the same age as my firstborn son would have been, had he lived. But he had not lived; instead I had suckled Princess Catherine and come to love her and, for that reason, now found myself here in her train on foreign soil with a lump in my throat.

I coughed, forcing out my next words. ‘Fathers can be hard to please. What does your mother think?’

His face grew solemn and he made the sign of the cross. ‘Sadly for us all, my mother died last year.’

My heart gave a little lurch to think of his grief for the mother so recently deceased. ‘God give her rest,’ I murmured. ‘But who is “us all”? Do you have brothers and sisters?’

‘Two sisters,’ he nodded, ‘younger than me. They try to run the house, but fifteen and thirteen is too young really.’

‘And who guards them while you and your father are away?’ I asked with concern. ‘They will need protection surely?’ Then I heard my own words and felt ashamed of their intrusive nature. ‘I am sorry. It is none of my business.’

He regarded me thoughtfully. ‘No, do not apologise. It is kind of you to take an interest. In truth it is an awkward situation because our aunt – my father’s sister – has recently come to live in the house. She is a widow but my sisters do not like her. Meanwhile, my father buries his grief in his work and does not notice.’ He gathered up his reins and clicked at his horse impatiently. ‘Hey, Dobbin, shall we get there today?’

I took his impatience with the horse to be an indication that he wanted an end to the subject so, after a pause while I urged my Genevieve to close the gap between us, I reverted to my original topic. ‘Have you been to Eltham before … er, Walter?’ I asked.

‘Once,’ he admitted, ‘on the way to Dover. I was only recruited into the royal household last month to serve the king on his return.’

‘It is a royal palace though, is it not? Is it much used?’

‘I believe the king has hunted there a number of times and the court came for Christmas a few years ago. I am told that his grace’s father liked it particularly, but of course the present king has been out of England a good deal.’

‘Yes indeed. He has seen more of Normandy than England lately,’ I observed. ‘What do your fellow countrymen think of that?’

Walter shot me an appraising glance. ‘Well the battle of Agincourt was a great victory, of course, so he is very popular.’

‘For us French it was a catastrophe,’ I remarked dryly.

I saw his cheeks colour. ‘Yes,’ he muttered awkwardly, ‘I suppose it was.’

‘What do the English think about having a French queen?’

His colour deepened further. ‘She is beautiful, Queen Kate!’ he exclaimed. ‘The people love her as soon as they see her, as you have witnessed.’

‘Yes, they do,’ I agreed, ‘and long may it last.’

‘Why should it not?’ Walter cried. ‘A glorious king and a beautiful queen – that is what the people want in their monarchs.’

Catherine may have thought she would miss King Henry’s company at Eltham but, in truth, there was little time for moping. Couriers brought letters daily, outlining the developing plans for her coronation and the surrounding celebrations; there were gowns to be tried and adjusted, headdresses to fit, veils and jewels selected to match each set of robes, visiting courtiers to entertain and for exercise, some hawking in the surrounding forest.

In the midst of all this, a group of court damsels rode in for her appraisal as maids of honour and over the following days I was happy to hear Catherine’s laugh ring out amidst a chime of girlish giggles as half a dozen young daughters of the nobility did their best to teach her some of the English court dances, while she attempted to teach them the French way to play bowls and they all swapped tips on the art of harmless flirtation. Catherine did not confide her thoughts to me but, as a close observer, I soon assessed which girls I hoped she would choose. Then, just before she was due to appoint them, the Duke of Gloucester threw a stone into still waters when he arrived at Eltham unannounced, bringing with him among his large retinue, a young lady. Within minutes of their arrival, a page came to Catherine’s solar to request audience with the queen for his grace of Gloucester and the Damoiselle Eleanor Cobham.

‘What does it mean this word “Damoiselle”, is it an English version of our “Mademoiselle?”’ Catherine asked her sister-in-law, the Duchess of Clarence.

We were all in the great solar, a royal presence chamber large enough to hold upwards of twenty people comfortably and had been listening to a new poem celebrating the royal marriage, penned by a poet called John Lydgate whom King Henry apparently much admired and patronised. It was written in English and, even though it was declaimed with great clarity by a professional player, Catherine had been frowning over the strange language and meter of the verse, so she looked quite grateful for the interruption.

‘Yes, more or less,’ allowed the duchess. The two royal ladies sat in canopied armchairs, while the young would-be maids of honour had grouped themselves around them on low cushioned stools and benches. ‘The title is used at court now to indicate a maiden of birth but not of noble blood. Her father is probably a knight ordinary, a lord of a manor but not a baron. She therefore does not merit the title “Lady”.’

‘I see.’ Catherine turned to Agnes with a smile, addressing her in French. ‘There you are then, Mademoiselle de Blagny. It seems that here in England you are a Damoiselle.’

Agnes and I were occupying a sill-seat in one of the solar’s long oriel windows, which protruded over the main courtyard of the palace and gave a clear view of the entrance to the royal apartments. We had witnessed the arrival of Gloucester’s entourage and exchanged intrigued glances as we watched the duke elbowing a squire away to personally help a young woman down from her horse in a way which had led me to assume she was at least a countess. Not so, it would seem. This must be the Damoiselle Cobham, although with the hood of her cloak pulled over her head against the chill weather, it had been impossible to see her face.

When she walked into the room, it was instantly obvious that Eleanor Cobham was a beauty; small in stature with glossy dark auburn hair smoothed under a little green veiled cap, a pale, unblemished complexion and huge black-lashed eyes the colour of violets. She was also very young, with all the grace of a yearling hind as she knelt before Catherine’s chair with her head bowed and her eyes modestly downcast, her robe a simple surcôte of pale-green wool, untrimmed and oddly old-fashioned, over a kirtle of cream linen with trumpet-shaped braid-edged sleeves. Compared to the bevy of stylish, blue-eyed blondes around her, with their bright-coloured houppelande gowns, rich fur trimmings and jewelled headdresses, she looked like a dainty wren among goldfinches.

The Duke of Gloucester bent his knee deferentially to Catherine. ‘God’s greetings to your grace,’ he said with one of his dentally perfect smiles and precise flourishes. ‘I beg to present Damoiselle Eleanor Cobham, the daughter of one of my ablest troop captains, Reginald Cobham, the lord of Sterborough. In return for valiant service under my banner at the siege of Cherbourg, I undertook to introduce his eldest unmarried daughter at court. Sadly her mother is too unwell to act in this capacity, but it came to my notice that you were appointing young ladies to your service as handmaids and attendants at your coronation, so I took the liberty of bringing the damoiselle here to Eltham, confident that you will find her entirely suitable for such a role in your train.’

Gloucester did not remain on one knee for long, moving to greet the Duchess of Clarence before stepping back to allow them both to inspect his protégée.

Catherine studied the crown of the little green cap with its pristine shoulder-length drop of white veiling. ‘Pray rise and lift your head, damoiselle, so that we may see your face, for I think it is a very pretty face,’ she said kindly, watching Eleanor’s graceful return to standing and the proud lift of her chiselled chin above the smooth, pale column of her throat. ‘But then all these young ladies display English beauty at its best, do they not, my lady of Clarence? Your daughter, Joan, not least among them.’

‘Indeed they do, your grace,’ agreed the duchess. ‘And you have wisely decided to choose your companions according to their sweetness of character and temperament, rather than their looks.’

‘Exactly,’ nodded Catherine. ‘So you see, my lord duke I cannot instantly grant any request to include the Damoiselle Cobham among them until I have enjoyed more of her company.’ Ignoring the duke’s frown of displeasure, she smiled at the newcomer. ‘Meanwhile, we are happy to welcome you, Eleanor, and I will ask Mademoiselle de Blagny to introduce you to the other young ladies and make sure you are comfortable, whilst I retire to learn more of the arrangements for my coronation from his grace of Gloucester.’

She rose from her chair and there was a rustle of skirts as we all rose with her but, before she departed, she cast a second glance at the damoiselle, who now appeared even smaller, measured against the others. ‘How old are you, Eleanor?’ she asked.

‘Fourteen, your grace.’ There was a slight hesitation and the girl blushed before adding, ‘That is to say, soon I shall be fourteen.’

‘Yes, I thought you were very young. Not yet fully grown, I think. Well, time will remedy that.’ Catherine addressed the duke directly. ‘Let us take refreshment in my privy chamber, my lord. I gather that as Great Chamberlain you have been making all the arrangements for the feast. Will you join us, Madame?’

This last was to the Duchess of Clarence, who expertly swept back her trailing skirt and followed the queen and the duke from the solar. As soon as the door was closed, a burst of chatter broke out among the assembled girls, several of whom clustered around the newcomer asking where she was from and whether they knew any of her family. Eleanor looked slightly startled, but obligingly answered their questions, although it soon became clear that her connections were not recognised.

Listening to this exchange, the French word parvenu sprang to my mind, and I noticed that while Eleanor’s eyes might be the colour of violets, there was nothing of the shy wildflower about her. In truth, this was a shameful thought on my part because if anyone was parvenu in the assembled company, it was me. However, Eleanor’s manner and dress were such as to make it obvious that here was a girl who was not from a vastly privileged background and who lacked the sophistication gifted by wealth and social position. I wondered if the Duke of Gloucester had done her any favours by dropping her in amongst these judgemental daughters of the English nobility and was minded to feel sorry for her. But at thirteen she already showed the composure of some young ladies of twenty and the cool self-containment of a high-bred cat; I decided that I could probably save my pity for those who needed it. If and when the Damoiselle Cobham entered the queen’s service, I suspected it would be only a matter of days before she displayed all the traits and skills of a seasoned courtier.

I had begun to wonder whether Catherine would ever seek my opinion of the candidates for her maids of honour and had more or less resigned myself to accepting whoever was foisted upon me, since it would inevitably fall to me to break them in, if that was the right term for showing these proud fillies how and in what ways they were expected to serve their queen with grace and humility. There were several among them who I thought might find the humility part of it hard to stomach.More encouragingly, there were some for whom it would be a natural extension of a careful upbringing. These latter were the girls I hoped would make the grade and I was gratified to have my opinion sought later that night when Catherine retired to bed.

‘Which of the young ladies shall I call to serve you tonight, Mademoiselle?’ I asked, pushing a poker into the embers of the fire ready to heat her bedtime posset.

She made a face. ‘None of them, Mette. They all look at me with such questing eyes, as if willing me to tell them they are chosen. I know their families are waiting and hoping they will be given a position. It is so important to them and I cannot bear to disappoint.’ She crossed to the prie-dieu and I thought she was about to kneel and pray, but instead she suddenly turned and wailed at me. ‘Help me, Mette! I do not know what to do.’

‘About the appointments?’ I spread my hands to indicate my hesitation. ‘What does the duchess say?’

‘She says I should take the ones I like best, but I believe the king would not think that the right thing to do. Some of them are of higher rank than others, some of their families deserve royal patronage more than others, and some would just make better attendants.’

‘Then I think you should take those,’ I said at once. ‘At least they should be at the top of the list. After all, there is no point in having people around you who are lazy or who resent the tasks they are required to do.’

‘Are there any who do that?’ She seemed surprised at the suggestion.

‘I have noticed one or two, Mademoiselle. Of course you would not see the faces they pull behind your back.’

‘No, of course not. You must tell me their names, Mette. And what about the Cobham girl – Eleanor? I think she is too young yet to be let loose about the court, but I am reluctant to offend the Duke of Gloucester. After all, he is the king’s brother.’ By now Catherine had sat down on a stool beside the hearth and was staring into the fire.

‘Why do you think the duke has singled her out?’

I tried not to inject my question with hidden meaning, but I must have failed because she glanced up at me, frowning. ‘He said it was as a favour to her father.’

‘Yes, but when does a royal duke ever owe a favour to a mere troop-captain?’ I pointed out. ‘It seems to me there is something not quite right about it.’

‘What are you trying to tell me, Mette? That the duke has lecherous intentions?’

‘I have no cause to think his grace of Gloucester unscrupulous,’ I said hurriedly. ‘The girl is very young, a beautiful child.’

She held up her hand sharply, cutting me off. ‘Yes, yes, I know. You need not say it. A young girl with her looks is always vulnerable, especially if she does not have powerful relatives to protect her. So you think I should send her back to her mother? And you are right. I will tell the duke that I will reconsider her in a year’s time. Let him be satisfied with that.’

I pulled the hot iron out of the fire and knocked the ashes off it before plunging it into a jug of spiced wine. A tantalizing aroma of fermented fruit rose in the sizzling steam.

‘And the other young ladies, Mademoiselle? Which of them will you have?’ I asked, reaching for a silver hanap from the nearby buffet.

She gave me a mischievous smile. ‘Unless you tell me they have been pulling faces behind my back, I think I will appoint the three Joans or Joannas or whatever they call themselves – they are all Jeanne to me. I know it will make for confusion, but we can use their surnames and they all seem pleasant and uncomplicated. Also Belknap and Troutbeck are from the north …’ Her brow furrowed in concentration as she struggled to pronounce the next words. ‘… Lanca-shire and York-shire I believe – and will be helpful keeping me abreast of matters in those far outposts of the kingdom. With Lady Joan and Agnes that will make five. What do you think?’

I answered her question with one of my own. ‘Do you not need six maids of honour to carry your train at the coronation, Mademoiselle? I hope you are not expecting me to line up with the young damsels.’

Catherine giggled. ‘And have the mother ewe plodding along beside the skipping lambs? No, no, Mette – that would never do. I will ask the beautiful Damoiselle Cobham to be the sixth train-bearer before she returns home to Sterborough – wherever that is. I hope that will appease the Duke of Gloucester as well as compensating the child a little. Now, Mette, tell me I am the queen of diplomacy.’

I made her a low curtsy. ‘You are the queen of queens, Mademoiselle,’ I assured her, offering the warmed wine. ‘I hope this is not so hot it scalds your grace’s sharp wits.’

4 (#ulink_2e342a22-17ca-5c06-8ea7-7589f4081e30)

‘What can I hear, Mette?’ asked Catherine when I drew back the bed-curtains at dawn. ‘It started a few minutes ago and I have been lying here listening, thinking it might be angels.’

‘It is a choir, Mademoiselle,’ I told her. ‘There are boys dressed all in white on the green below your window and they actually look rather like angels, only lacking wings. They are here to herald your coronation day.’

‘That is very special. They sound wonderful.’ Catherine made to sit up but hastily snuggled down again. ‘Blessed Marie it is cold! Those poor boys, how can they sing in this frost? They need something to warm them. Will you make sure they get hot drinks, Mette?’

‘I will send a page with your orders at once, Mademoiselle,’ I assured her. ‘But do not let your own drink get cold.’ I had placed a cup of warm buttermilk and honey at her bedside. I held out her chamber robe and with reluctance she shed the covers, quickly stepping down from the bed to don the fur-lined robe. ‘The fire has been burning all night so you can warm yourself at the hearth.’

At last the day of her coronation had arrived and, following a tradition begun by England’s first King Henry, Catherine had spent the night in the Tower of London.

The previous morning she and the king had left Eltham at dawn, mounted on white horses, bells jingling on their harness and tasselled trappings of scarlet and blue boldly displaying the lions of England and the fleurs-de-lys of France. They were met on Blackheath Common by the city’s mayor and aldermen who had ceremonially escorted them through the narrow shop-lined thoroughfare that crossed London Bridge and into the crowded and festooned streets of the city. I had not taken part in the parade that followed, but Catherine had excitedly described it when she returned at dusk.

‘London is magnificent, Mette. Hundreds of bolts of cloth of gold had been distributed by the Guild of London Mercers and hung from the windows of the houses where they billowed in the breeze, turning the streets into a golden pathway. It was truly magical. A holiday had been declared and the roads were free of foul-smelling rubbish and lined with young girls in white kirtles with baskets full of dried herbs and rose-petals to throw under our horse’s hooves so that we smelled only fragrant perfumes as we rode. For the duration of the parade the fountains ran with wine, although as you know King Henry has an abhorrence of drunkenness and had ordered it diluted with spring water. Even so, there were plenty of people in very high spirits. Spectators crammed every vantage point, blowing trumpets and horns, and some of the more agile citizens leaned from attic casements or perched on rooftops and even clung to church steeples to get a clear view. I was fearful that someone might fall, but no one did, as far as I know.

‘There was plenty for them to see. On raised platforms at each crossroads mummers staged biblical tableaux celebrating marriage and monarchy and outside every church on the route choirs sang psalms and anthems. Fifty knights of the king’s retinue rode before and behind us flying their brightly coloured standards and wearing full suits of armour, which glinted in the sunshine. Then, mounted on bright chestnut palfreys behind them were my six maids of honour attracting deafening cheers and whistles – and so they should have, in their blue fur-trimmed mantles and sparkling jewelled headdresses. We made a circular route through the centre of the city, stopping at St Paul’s church to hear a celebration mass, and then to a feast in the Guildhall before returning along the river, past moored barges, docks and warehouses all decked with flags and crammed with more cheering crowds of people. I have to admit that today we were more enthusiastically greeted than when we rode into Paris last Christmas.’

I had left the royal cavalcade after crossing London Bridge and ridden with the household servants and baggage straight to the royal apartments in the Tower of London, on the city’s eastern flank. The quiet of the inner ward, where I had spent the day supervising the queen’s unpacking, was suddenly broken by the fanfare of trumpets. I found a window from which to watch the returning procession as it clattered over the drawbridge that spanned the moat, past the Lion Tower where the king’s animals were housed, through the massive gatehouse, under another gatehouse and into the inner ward. Steam rose from the horses’ flanks and the riders’ cheeks were flushed bright red, their breath condensing in the icy air as daylight faded. A hot tub awaited the queen before a blazing fire, not only to warm a body stiff and chilled by the February wind, but even more importantly to begin the purification process essential before the divine rite of coronation.

The queen would make a lone vigil ahead of the solemnity of coronation. Having escorted his queen formally to her lodgings, the king immediately rode away again to Westminster, leaving the Archbishop of Canterbury with Catherine in the royal chapel of St John. The archbishop spent an hour explaining the vows she would be taking and the indelible nature of the sanctity which anointment with the holy chrism would bestow. When she emerged, she looked pale and slightly dazed and went immediately to the small oratory beside her chamber, where she dropped to her knees before the portable altar that always travelled with her with its precious triptych of the Virgin.

Each of the maids of honour had been given particular duties regarding the queen’s personal grooming – meticulous washing, trimming and brushing and the application of fragrant unguents – but I knew that if Catherine wished to pray, these treatments would have to wait. The wooden tub, draped in fresh white linen and set before the fire in the royal solar, had to be refreshed with hot water and re-draped three times before the queen felt that the preparation of her mind and soul for coronation could give way to the smoothing and soothing of her body and its ritual cleansing.

I waited with her in the little oratory, standing quietly in the deep shadows cast by the flickering wax pillar candles. When she rose from the prie-dieu and turned to leave, she noticed me there, smiled at me wistfully and moved close to whisper, ‘I do not feel worthy, Mette. I fear the filth of Burgundy will never be prayed away.’

There was no one else to hear us but, nevertheless, I replied in the same hushed whisper, ‘You have said yourself that the crown is your destiny, Mademoiselle. You did not allow that devil duke to snatch this marriage from you and now your coronation will demonstrate forever your high worth in the eyes of God.’

Although nothing had been said, I was intuitively aware of Catherine’s fervent hope that the crowning ritual would bring a spiritual rebirth that might banish once and for all the dark memories of the torrid abuse inflicted on her by Jean, Duke of Burgundy; appalling ill-treatment which had ended only with the violent death of the duke, murdered in the presence of, if not by the hand of, her brother Charles. I had prayed that her marriage to King Henry would allow her to set the past aside, but it seemed it might take more than that.

‘Perhaps the weight of the crown will finally instil a sense of right,’ I added gently; ‘that and the birth of an heir.’

She closed her eyes and crossed herself. ‘I have been begging Our Lady for both, Mette. I earnestly pray that she will intercede for me and that I will emerge from the abbey tomorrow fortified with God’s divine strength and ready to carry the heir that our countries demand.’

When her eyes opened, the expression of determination in their deep-blue depths startled me. Looking back, I had not anticipated how fundamentally the catharsis of coronation might affect her.

Over recent days two of the three Joannas (they all shared the extra syllable to their name) had formed a tight friendship, always keeping together and helping each other in the performance of their tasks. Joanna Belknap and Joanna Troutbeck were both from the north of England and seemed to possess a certain down-to-earth practicality. In order to differentiate between them, Catherine had decided to call them by their family names, a habit which made life easier for the rest of us but which did not please the third Joanna whose name was Coucy, a solitary girl not given to smiling readily or volunteering for anything. She complained out of Catherine’s hearing that she considered being addressed only by her surname to be disrespectful. When I suggested that being in the service of the queen and addressed by name at all could only be deemed an honour, she gave one of her habitual, dismissive sniffs. Through careful enquiry I discovered that the Coucy family held, among others, the estate and barony of Dudley, which included possession of a substantial castle, and that her father had served King Henry in France and was recently appointed a court official. The Coucys were what might be described as ‘top-rank’ and very conscious of the fact.

When all six young ladies came to dress Catherine on the morning of her coronation Coucy, sniffed and sneezed and complained about the penetrating chill of their allotted rooms at the top of the White Tower, but Eleanor Cobham remarked on the glorious view to be had from its windows.

‘They are calling it “coronation weather”, your grace,’ she told Catherine, kneeling to present the first of the queen’s fine white hose, embroidered with fleurs-de-lys to signify her French royal lineage. ‘From our chamber you can see across the River Thames and miles out over the countryside. I think today you might even be able to see as far as my father’s manor of Hever!’

Catherine merely smiled and raised her eyebrows, being distracted by Agnes who was polishing her long pale-blonde hair with a silken cloth to make it glossy, but Coucy gave another of her chronic sniffs and commented tartly, ‘Hever? I thought you came from some place with a borough in it, Cobham.’

‘Yes, my home is at Sterborough,’ Eleanor agreed equably, affecting not to notice the other girl’s scornful tone, or her use of the surname. Joanna Coucy had decided that, since she was to be addressed by her family name, she would call all her fellow maids of honour by theirs. ‘But my family has rents from more than one manor, as I am sure does yours. Hever is one of them.’

‘Not manors,’ responded Coucy scathingly. ‘My family has estates – and more than one of those.’

Catherine eased her foot gently into the toe of the pale hose and stretched out her leg for it to be rolled up. Without turning she said, ‘Is it not your task to raise my skirts, Coucy, to allow Eleanor to pull up the hose? And you might remember, while you boast of your estates, that they are granted to your father by the king and what is granted may also be withdrawn.’

Joanna Coucy flushed bright red, muttered an apology and carefully lifted the skirts of the queen’s chemise and chamber robe. I watched Eleanor duck her head to hide a smirk as she tied one cream satin garter and wondered how long Coucy would keep her place at the queen’s side.

Catherine wore two kirtles for her coronation – one of fine ivory Champagne linen directly over her chemise and the other of more substantial weight, for warmth when she was ceremonially stripped of her grand outer robes before her anointing. This second garment was a tunic of heavy white silk, lined with a layer of soft shaved lamb’s wool and sewn with tiny seed-pearls. It had tight sleeves with long trailing tippets of ermine. Around her neck was draped a white stole of the type worn by bishops and senior clergy, lavishly embroidered in shimmering gold thread. At the anointing, and before the crown was set on Catherine’s head, this stole would be removed to allow the sumptuous ivory velvet houppelande gown made for her in Paris to be drawn on and fastened with four fabulous diamond-studded clasps which were part of her French dower, followed by the crested, crimson, ermine-trimmed mantle of state, the train of which was twenty-feet long. Abbot Haweden of Westminster was due to officiate at the anointing, and he would keep the stole as a reward and a memento of his pivotal role in Catherine’s transformation from ordinary mortal to one of God’s divine representatives on earth.

In the Abbey Church of St Peter, I squeezed into the north transept among the officials of the royal household, where we had a clear view of the raised chancel and the high altar. There the carved and gilded throne stood on a stepped dais in the centre of a beautiful mosaic pavement, laid in squares and circles of brightly coloured stone and glass. Above it heraldic banners hung from the ceiling vault, showing the honours and devices of all the English Kings since William of Normandy. And so, as the ceremony began, I was able to raise my voice in loud approbation along with the great congregation of barons and ladies, when we were asked if we would have Catherine as our rightful queen. She looked modest and graceful in her embroidered white kirtle with her hair tumbling loose from a simple circlet of gold as she was escorted to each corner of the chancel by King Henry and the abbot and their demands for approval were swamped by loud shouts of ‘Aye, we will!’

Then she was led to the altar by the Archbishop of Canterbury, where she made her solemn vows, speaking the Latin words fluently and without mistake. A lump came to my throat as I watched her prostrate herself before the great gold crucifix while the choir sang an anthem of dedication. She lay on cushions with arms outstretched in total supplication and inside my own head I could almost hear her fervent prayers that a great and compassionate God would demonstrate her worthiness to be queen by removing her burden of guilt and granting her an heir for England’s crown.

Her maids of honour came forward to raise her up and remove the stole and circlet. While the choristers sang a plangent benediction, she stood waiting, head bowed, under a cloth of gold canopy held by the four highest-ranking noblewomen of the court. Then the archbishop advanced to anoint her with the holy chrism on her forehead, intoning solemn prayers of dedication and intercession. Another anthem was sung while the holy oil was carefully wiped from her skin with a soft cloth, which was carried to the altar and placed reverently in a jewelled pyx. Then she was robed in her coronation garb and taken in procession to be enthroned.

During this procession the train of Catherine’s heavy ceremonial mantle was carried three to each side by the maids of honour. Halfway across the chancel, without warning or apparent cause, Joanna Coucy suddenly tripped. By a supreme effort she managed to save herself from tumbling to the floor but not without jerking the mantle and pulling Catherine to a halt.

The procession resumed directly, but the gasp of dismay I had heard reminded me of when the Duke of Gloucester had tripped on the Dover shore. While all attention was on the king, who stepped forward to formally place Catherine in the throne, I kept my gaze fixed on the maid who walked last in the line of train-bearers, a pace behind Joanna Coucy. It was Eleanor Cobham and on her lips there played an enigmatic, smug little smile. I could not help suspecting that Eleanor had deliberately trodden on Joanna Coucy’s skirt and made her trip in order to pay her back for slighting her family earlier in the day. Eleanor Cobham may have been the youngest of the maids of honour but she was far from being the meekest.

A glorious fanfare of trumpets and the sound of soaring soprano voices raised in a triumphant ‘Vivat Regina!’ and ‘Long Live the Queen!’ announced the moment the crown was placed reverently on Catherine’s head by the archbishop. The crown was a precious and ancient relic of English history first used by Queen Edith, consort of the saint-king Edward the Confessor, who was buried behind the altar only yards from the coronation throne and whose shrine and sanctuary was a much-visited place of pilgrimage. We French often expressed scorn for the Saxon people who had been conquered by the armies of Normandy nearly four hundred years before, calling them uncouth and uncivilised, but if the workmanship of that crown was anything to go by such disparagement was sadly misplaced. Dozens of highly polished gems of every size and hue were set in a coronet of gold surmounted by pearl-studded cross-bars centred on a finial carrying a diamond the size of a goose’s egg. It was a crown just light enough for a lady’s head, but grand enough for an empress’s regalia and wearing it, with two gold sceptres placed in her hands, Catherine was transformed from a beautiful young girl into a regal figure of power and patronage, an icon of sovereignty. I could not tell what was going on in her head, but in mine a subtle alteration was taking place. I felt my eyes fill with unbidden tears. The image of the infant Catherine tiny and helpless at my breast seemed to be slipping from my mental grasp, to be supplanted by this awesome figure of authority, crowned with gold and precious stones and invested with the symbols of earthly and divine power.

King Henry did not attend Catherine’s coronation feast. He explained that it was because the rules of precedence dictated that if he were there she would not be the centre of attention, would not be served first and her new subjects would not do her full honour, being obliged to bow the knee to him first. Disappointed though she may have been, in his absence she was unquestionably Queen of the Feast. The highest nobles in the land acted as her carver, server, butler and cupbearer, while two earls knelt at her feet throughout the meal, holding her sceptres. The Earl of Worcester made an impressive spectacle riding up and down the centre of Westminster Hall on his richly caparisoned horse, ostensibly to keep order, and the Duke of Gloucester, in his role as Great Chamberlain of England, strode grandly about displaying his physique in a short sable-trimmed doublet of gold-embroidered red satin, brandishing his staff of office and directing the seemingly endless parade of dishes and subtleties.

In truth it was more of a pageant than a meal, a feast for the eyes rather than the stomach, as course after course was presented, each one more magnificent than the last and, because Lent had begun the previous week, all consisting of fish in one form or another. I had never seen so many different sea foods presented in so many guises. Anything that swam or crawled under water and could be hooked, trapped or netted had been turned into a culinary masterpiece; sturgeon, lamprey, crayfish, crab, eel, carp, pike, turbot, sole, prawns, roach, perch, chub – roasted, stewed, jellied, baked or fried, embellished with sauces or topped with pastry confections – culminating in a spectacular roasted porpoise riding on a sea of gilded pastry and crowned in real gold. It was all too much for me, but the great and good of the kingdom seated around me on the lower floor of the hall clearly relished it. From her royal dais, the new queen consort smiled and nodded at her subjects, admired the extraordinary skill of the cooks and, I noticed, consumed scarcely a morsel.

In the absence of her husband, seated beside the newly crowned queen was a pleasant-faced young man who also wore a crown; King James of Scotland who, although a monarch in his own right, did not outrank Catherine because he was a king without a kingdom. It was the first time they had met and his story was one which kept Catherine spellbound for much of the feast and earned her heartfelt sympathy. So much so that she regaled us with it at length the following day.

‘King James told me that there are warring factions in Scotland, just as there are in France and that his older brother, David, the heir to the throne, was starved to death in a castle dungeon by his uncle, the Duke of Albany. Fearing that James might also fall into Albany’s clutches, his father, King Robert, put him on a ship to France for safety. He was only twelve. Just think how frightened and lonely he must have been. And before he got near France, his ship was boarded by pirates off England. When they discovered his identity, they sold him to the English king, my own lord’s father, who then demanded that the Scots pay a vast ransom for him. When word of this was brought to King Robert, he fell into a seizure and died; so Albany achieved his evil ambition, took power in Scotland and the ransom has never been paid.’

At this point she gave me a meaningful look. She was thinking, as I was, of the parallels between this story and the civil wars between Burgundy and Orleans which had shaken the throne of France and led to her own marriage treaty, in which King Henry had supplanted her brother Charles as the Heir of France. However, she made no reference to it and continued her tale of the hostage king.

‘King James says the English have always been kind to him, particularly my own lord, the king’s grace, and the recent death of Albany has set the stage for the ransom to be paid. So, since under the rules of chivalry it is a queen’s prerogative to plead just causes, I mean to ask the King of England to instigate the King of Scots’ return to his kingdom.’ She clapped her hands with delight at the prospect of exerting her new powers.

‘Incidentally, little Joan,’ she turned to address Lady Joan Beaufort, who was gazing absent-mindedly out of the solar window, no doubt wishing she was galloping over wide-open spaces to the cry of the hunting horn, ‘King James made particular mention of you during the feast. He pointed you out to me, asked your name and who your parents were. I think you might have made a conquest there.’