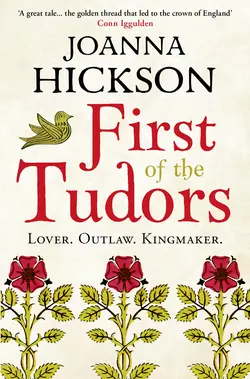

First of the Tudors

Joanna Hickson

‘A great tale… the golden thread that led to the crown of England’ Conn IgguldenJasper Tudor, son of Queen Catherine and her second husband, Owen Tudor, has grown up far from the intrigue of the royal court. But after he and his brother Edmund are summoned to London, their half-brother, King Henry VI, takes a keen interest in their future.Bestowing Earldoms on them both, Henry also gives them the wardship of the young heiress Margaret Beaufort. Although she is still a child, Jasper becomes devoted to her and is devastated when Henry arranges her betrothal to Edmund.He seeks solace in his estates and in the arms of Jane Hywel, a young Welsh woman who offers him something more meaningful than a dynastic marriage. But passion turns to jeopardy for them both as the Wars of the Roses wreak havoc on the realm. Loyal brother to a fragile king and his domineering queen, Marguerite of Anjou, Jasper must draw on all his guile and courage to preserve their throne − and the Tudor destiny…

Copyright (#ulink_3ec9f37c-d86d-50ea-a1e9-f14d18ffc748)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Copyright © Joanna Hickson 2016

Cover design: Holly Macdonald © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016

Cover illustration © Chris Cooper-Smith / Alamy

Joanna Hickson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008139704

Ebook Edition © December 2016 ISBN: 9780008139711

Version: 2018-09-24

Dedication (#ulink_3ab8f320-1fcc-5177-a3aa-1664c7fa7395)

For my gorgeous granddaughter Lyra Joanna Second of the Ashtons Conceived, gestated and delivered Along the same timeline as First of the Tudors

Contents

Cover (#u24e18a4e-c6a5-5302-a9d0-bdd2f4609bce)

Title Page (#uf5737ffb-4bc4-5ab9-9e6f-5f0888a30667)

Copyright (#ufb9cdf40-bd2d-5ae0-9029-7961851d9372)

Dedication (#u7e65c359-437d-5f16-baf8-5540f1337c17)

Family Tree (#u13c10199-d00e-5bbe-8eb7-3a641d524db6)

Maps (#u781206c9-eee7-50e0-8484-0bcf22ed5826)

Part One: Brothers to the King (#u0a85ebac-c446-55b6-974a-0eeb26c5443f)

Chapter 1: Jasper (#u861fb4e2-2119-59cf-bb0a-3b28ca4f0c9e)

Chapter 2: Jane (#uc8ef8cd0-a11d-5ff9-b789-b4ffbac92fa9)

Chapter 3: Jasper (#u6dcee4d0-071f-5efe-81f6-7423ddebc958)

Chapter 4: Jasper (#ud5bede73-ab16-5cfe-9632-437ee6015ced)

Chapter 5: Jasper (#u6233ec04-21a6-5a88-aef1-d4e3ee94e22b)

Part Two : The Tudor Earls (#ud3958911-8752-5626-bc5b-9a6e926e2eb3)

Chapter 6: Jane (#u8a603858-bcc5-5368-982c-1abe9bf82164)

Chapter 7: Jasper (#ufcfab011-03be-5514-9659-543a682a640c)

Chapter 8: Jasper (#u0bbb8aa4-b8ae-5177-858b-9c945d5a54d5)

Chapter 9: Jasper (#u4572a4e8-7291-5813-b371-e7953e2e5681)

Chapter 10: Jasper (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11: Jasper (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12: Jane (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13: Jane (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14: Jane (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15: Jasper (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16: Jane (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17: Jane (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18: Jasper (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19: Jane (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20: Jasper (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21: Jane (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22: Jane (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three: Hostilities (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23: Jasper (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24: Jasper (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25: Jasper (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26: Jane (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27: Jasper (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28: Jane (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29: Jasper (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Four: Two Crowned Kings (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30: Jane (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31: Jane (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32: Jasper (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33: Jasper (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34: Jane (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35: Jane (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36: Jane (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37: Jasper (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38: Jasper (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39: Jasper (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Five: The Return (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40: Jane (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41: Jasper (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42: Jasper (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43: Jasper (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 44: Jane (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 45: Jasper (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 46: Jane (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 47: Jasper (#litres_trial_promo)

Glossary (#litres_trial_promo)

Welsh Words and Names (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading Tudor Trilogy (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Joanna Hickson (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Family Tree (#ulink_6374fa14-e7ef-5353-adb2-1932709e9998)

Maps (#ulink_5f9a0ac9-461b-5b11-8a09-ce04d15fc11e)

PART ONE (#ulink_6a14db13-957d-547c-a420-ff3fd35fd072)

Brothers to the King (#ulink_6a14db13-957d-547c-a420-ff3fd35fd072)

1451–1453

1 (#ulink_0aead324-b225-55d1-8f7d-689895ada881)

Jasper (#ulink_0aead324-b225-55d1-8f7d-689895ada881)

Westminster Palace & London

FLASHES OF IRIDESCENCE GLEAMED like fireflies in the gloom of the small tower chamber. I stared at the river of fabric as it settled in graceful waves across the bed. It was the intense blue of a noon sky, yet it glittered with the gold of midnight stars. ‘Do you think she will like it?’ Edmund asked.

I took a deep breath, hesitating to prick my brother’s bubble. ‘Yes – and no,’ I said.

‘What do you mean?’ Indignation raised the timbre of his voice. ‘Jesu Jas, a gown fashioned of such fabric would make any female feel like a queen!’

My hackles rose. I hated Edmund calling me Jas and had told him so on numerous occasions, yet still he persisted. It was a boyhood nickname and we were no longer boys but squires in the service of the king, soon to become knights. My name was Jasper. I had stopped calling him Ed on the day we came to court.

‘But she is not a queen and there are sumptuary laws. Our sister could be royally fined for wearing a gown made from such fabric. You know its use is restricted to royalty, archbishops and the effigies of saints.’

I touched the cloth, admiring its shimmer as the slight movement stirred it into life; it was soft and sinuous under my fingers. I imagined the deft fingers that had wound the fine gold wire around the warp fibres with infinite skill and patience. Edmund was right; wearing it would make anyone feel illustrious. Cloth of gold! Just how had Edmund come up with the huge price it commanded?

Edmund drew himself up to his six-foot height. ‘The daughter of a queen may wear what she likes. They would not dare to fine her.’

Exasperated, I flicked the fabric so that it rippled, like a sudden flurry on a calm lake. ‘Your head is in the clouds, brother. Come back to earth. Our sister lives in Tun Lane, London. Nobody knows what we know. In her world she is not Margaret, just Meg, and she is about to marry the man of her choice who is not a prince but a lawyer. She will be a wife and, God willing, a mother. She is happy, with a warm home and enough money for her needs. Whatever you dream for your own future, do not wish it on her.’

Irritably Edmund twitched the length of fabric into his arms, gathering it in like a shield against reality. ‘I know what she is – what she has chosen to remain – but she is still the daughter of a queen, the granddaughter of a king, and I will give her the honour of royal raiment, even if she never wears it.’

I shrugged. ‘So be it but you have wasted your money. And do not dare to reveal her true birth by so much as a whisper at the wedding or you will win Mette’s enduring wrath – and mine too for that matter.’

My brother paused in his careful folding of the cloth-of-gold. ‘Mette – is she still alive then?’

Unlike me, Edmund no longer went to The House of the Vine in Tun Lane where our sister had lived since the death of our royal mother fourteen years ago. In recent years he had acquired what I considered an exaggerated sense of rank and the refuse-strewn back streets of London offended him.

‘Of course she is alive. You know she is. She always asks after you, as does our sister.’ Mette was Meg’s foster mother, the faithful servant into whose care our own mother had entrusted her little daughter on her deathbed, hoping she might enjoy the happy childhood she herself had not known. Our mother was one of many children of the sixth King Charles of France and the ravages of the king’s madness had had consequences for them all in the fierce struggle for power that resulted. Now Meg was to marry her foster brother William, who had recently qualified as a lawyer at the Middle Temple. A spring wedding at St Mildred’s church.

‘And what do you tell them?’ Edmund asked as he laid the cloth on top of his chest, which stood next to mine against the wall in our chamber in one of the many towers of Westminster Palace.

‘I tell them you are well. That is all.’

Edmund’s chest was filled with apparel of every kind. I had wondered before how he managed to afford such finery since he received the same royal pension as I did. I presumed he must be winning at dice or frequenting the moneylenders of Lombard Street, like many of our fellow squires. I hated debt and could do without fashionable clothes, preferring to buy harness and armour if I had any spare funds but I did quite envy the dashing figure Edmund cut about the court.

‘You are coming to the wedding, are you not?’ I added. My query contained a note of anxiety for Edmund could be unreliable.

‘Of course I am coming. I would not miss a feast.’ A smile revealing perfect teeth lit his dark features – another advantage he enjoyed, my own smile being marred by a chipped front tooth, the result of an unhappy collision in a joust. ‘What are you giving her?’

I felt the blood rush to my cheeks. A tendency to blush was one of the drawbacks of having red hair and a fresh complexion. There was no reason to feel ashamed of my gift, yet I knew Edmund would think it niggardly. ‘A hogshead of ale.’

‘Ale?’ He was incredulous. ‘You are giving them ale?’

‘Yes, the traditional Bride Ale, strongly brewed and flavoured with herbs and honey, for all the guests to drink their health.’

Edmund grimaced and flicked back his glossy hair. ‘Oh well, I daresay there will be wine as well. After all, their name is Vintner. There are plenty of wine merchants in the family.’

* * *

Meg and William Vintner were married at St Mildred’s church in the London ward known as the Vintry, the same church that had witnessed the nuptials of his parents more than twenty years before. As the bride and groom stood in the porch making their vows, I studied the face of the woman who had brought them both up. Mistress Guillaumette Vintner, known to close friends and family as Mette, was now a matron of sixty-three years, stout and wrinkled in her wimple and veil to which, on formal occasions such as this, she added a widow’s barbe to mark her lone status since the death of her husband Geoffrey several years before. They had enjoyed seventeen happy years of marriage before he had succumbed to congestion of the lungs and once or twice I saw her gaze wander wistfully off towards the churchyard where he lay buried. The bridegroom, their only son William, had been what she called their ‘autumn leaf’, the last fruit of their fertility before the sap began its winter retreat, and no one could have been more delighted than Mette when the relationship between William and Meg changed from the affection of siblings to the attraction of adults. Probably Geoffrey had foreseen their future together too before he died. Somehow it seemed inevitable. Meg had been Queen Catherine’s secret bequest to the woman who had been her wet nurse as a babe and whom she had come to regard as a true mother.

Owen Tudor stood beside Mette. Father to Edmund, Meg and me and still handsome, with his silver hair and ruddy complexion, he had travelled from the Welsh March for the occasion. I knew he still practised regularly with sword and bow, which kept his physique that of a man ten years younger than the fifty he had lived and I admired him for it. Nor did he appear to have lost any of his ability to charm the ladies; more than once he caused Mette to blush and smile at his whispered comments as the short ceremony progressed. He also aimed a sly wink at Edmund and me, which I returned but which made Edmund hiss through his teeth. I think my brother would rather it had been our mother, Queen Catherine, who survived to attend the wedding, instead of the Welsh squire she had married in secret and to whom she had borne four children. Edmund was the eldest. Our younger brother Owen, the child born shortly before our mother passed away, was now a monk at Westminster Abbey and had taken another name.

Edmund’s wedding gift was wrapped in plain linen and draped over his shoulder. He was clad in a bright green damask doublet lined with scarlet, the sleeves dagged and his hose parti-coloured, one leg white and one yellow. The sight had attracted startled glances as we walked from the inn to the church.

‘Why do they stare like that?’ he had grumbled. ‘Have they never seen dagged sleeves?’

‘It might be your legs rather than your arms,’ I responded. ‘A short doublet and hosen like that are rarely seen in London streets.’

‘And no wonder,’ he declared, stepping gingerly over small piles of animal droppings and rotting vegetables. ‘I thank Saint Crispin that I thought to wear bottins rather than shoes.’

After the wedding Mass we walked in procession to Tun Lane, behind a group of beribboned minstrels who rivalled Edmund for colourful apparel and played merry tunes to set the mood. A spectacular array of wafers and pastries was laid out in the panelled hall at the House of the Vine and we were promised a feast of roasted meats when the banquet began. As I kissed the bride and groom and wished them well I noticed that my hogshead of Bride Ale stood in pride of place below the salt, ready for folk to fill their jugs at will. Meg thanked me warmly for it and while other guests gathered around the barrel Mette took me off to sit with her by the hearth. People were taking their places at the cloth-draped boards decked with spring garlands and their flowery scent vied with the smell of yeast and herbs as the ale flowed. Casting a scathing glance at the hogshead, Edmund wandered off to find some wine to drink.

‘That was a very thoughtful gift, Jasper,’ Mette said, ‘just what every wedding needs to get the conversation flowing. It is so good to see you – and Edmund too of course, although I barely recognized him. I must say his taste in clothes has taken an exotic turn!’

I laughed at that. ‘Still not mincing your words then, Mette? Of course at court Edmund’s style is hardly remarkable. It is mine which stands out as being rather bland.’

The old lady perused my best blue doublet with its grey coney trimming. ‘You both look as you choose,’ she commented tactfully. ‘And I hear the king favours sober dress. Are you still happy at court? Not swamped by the ceremony or daunted by the protocol?’

‘No, we have our duties and the company is fair. Plenty of other squires to spar with and the food is good.’ I grinned at her. ‘Better than at the abbey!’

After our mother’s death, our parents’ marriage became known and our father had been imprisoned for contravening the Marriage Act. Edmund and I had found refuge with the nuns at Barking Abbey on the Thames outside London, living among a group of young royal wards being educated there. Only when our half-brother, King Henry, reached his majority was our father released and we were brought into Henry’s own household, where tutors and instructors were engaged to prepare us for knighthood, a process which was now approaching its conclusion. It had been a change of lifestyle much appreciated by both of us.

Mette’s rheumy eyes crinkled. ‘Ha! I can imagine. And damsels? Does the queen keep a charm of goldfinches in her solar to delight the young men at court?’

‘She does, but none outshines her. It must be owned that Queen Marguerite is dramatically beautiful. They say that her dark eyes and skin are inherited from her Spanish grandmother.’

Mette sniffed and leaned forward to speak in a confidential whisper. ‘And that does not endear her to the English, especially as she has not yet produced an heir to the throne. As your mother knew only too well, in a queen beauty is no substitute for fertility. Besides Queen Marguerite is actually French, whom the English dislike even more than the Spanish, or the Welsh for that matter.’

‘Which is the very reason I am careful to avoid revealing my doubly unpopular origins.’ I shot her a wry look. ‘You are French, Mette. Have you found the English much prejudiced against you?’

Her smile was reassuring and rather nostalgic. ‘No, but I live very quietly now. Your lady mother did though – very much so; but then if she had not she would never have married Owen Tudor and retired into obscurity – and you would not have been born.’

‘Did I hear my name? Are you gossiping about me, Madame Mette?’ My father had approached the hearth and with his usual gallantry removed his rakishly feathered hat, bowed over Mette’s hand and kissed it.

She responded with a broad smile and a raised eyebrow. ‘From what I hear you do not need me to spread gossip about you, Master Tudor.’

My father looked affronted. ‘Now what are they saying in the city? None of it will be true of course.’

I pricked up my ears. Unless invited to attend the king, our father wisely avoided the royal palace these days, but when he was in London I often met him in one of the taverns clustered around Westminster Hall, where the courts of justice sat. Any rumour Mette had picked up would have come through her lawyer son William.

She gave Owen a stern look. ‘They say you are making the most of your new appointment as King’s Forester in North Wales; working your way through the poor widows of Denbighshire.’

Owen gave a loud hoot of laughter and his deep brown eyes, so like my brother Edmund’s, danced with delight. ‘I told you there would be little truth in what you heard. Is it likely that I would take up with any poor widow, Mette? I may have dallied with one or two rich ones – nothing more I assure you.’ With a polite display of reluctance he released her hand. ‘But you have no refreshment I see. At the risk of heaping more fuel on the flames of rumour, let me play your cupbearer and bring you a draught of the Bride Ale.’

Mette accepted his offer with alacrity and watched him cross the floor on his quest. Turning back to me she murmured confidentially, ‘After all, why should he not seek consolation where he can find it, Jasper? He is still a handsome man – but there is no woman alive that could ever fill the space in his heart left by your beautiful mother, so sadly taken from us, we all know that.’ As she spoke I spied a nostalgic tear escape her eye. She went on, ‘I see her face every time I look at Meg. I cannot think why the world does not recognize the truth of her birth. And yet I thank God it does not.’

I cast a glance at the bride and groom standing in the centre of the room, pledging their love in a shared cup. At twenty-one William Vintner was an affable and good-looking young man. Only a few weeks younger than Edmund, he was quick of wit and slow of ire, neither tall nor short with a sturdy build, curly brown hair and rosy, clean-shaven cheeks. He bore a strong resemblance to his genial father, a man I had greatly admired, but his beard did not yet sprout thick enough to warrant letting it grow as Geoffrey Vintner had. I was less than a year younger than William and in our infancy at Hadham Manor he, Edmund and I had been close playmates, but my brother seemed to have forgotten that. Out of the corner of my eye I saw Edmund leaning elegantly against the hangings, alone, sipping from a horn cup, his gaze sweeping the other guests with an unfathomable expression. He had yet to congratulate the young couple, or give them his gift.

Our sister was slim and fair with delicate features, deep blue eyes and a countenance of doll-like sweetness, which I knew concealed a strong will and a generous nature. If it were true that she closely resembled our mother then I cursed the weakness of my memory, which retained no clear image of Queen Catherine to compare her with. I had been six when she rode away from Hadham Manor, never to return. Only six years old when our lives turned upside down, and while I could remember every detail of the island in the River Ash where we three little boys had played at knights and outlaws, to my deep regret I had no recollection of the lovely face of our mother – the fifth King Henry’s widowed queen and Owen Tudor’s late and much lamented wife. I knew that somewhere in Windsor Castle there was a portrait of Catherine de Valois, painted when she was a princess of sixteen and sent to the conquering King Henry as a marriage-bait, but as yet I had not found it.

Mette was enjoying her ale, raising her cup to the bridal pair, when Edmund moved out from behind a knot of guests, ushering a servant who carried a joint-stool and spread it open to place it before the bride and groom in the centre of the hall. On it, with a ceremonial bow, my brother laid his wedding gift, still wrapped in its protective linen shroud. The room hushed expectantly as he stepped forward to kiss his sister, then, taking a proud stance beside the stool, he cleared his throat to speak. Although my stomach lurched with dread of what he might say, I thought what an impressive figure Edmund made despite the garish nature of his clothing, darkly handsome, with all the grace and sinew of a noble horseman.

‘Like all here, I have come to wish the bride and groom health, wealth and happiness in their life together. This gift is for the beautiful bride, so that she may array herself like a queen and show the world her true worth.’

With a deft movement he pulled off the linen wrapping and flung the exposed cloth-of-gold across his raised arm in a dramatic flourish. Beams of light falling through the open hall shutters reflected off its folds and illuminated the faces of the surrounding guests, who stood open-mouthed at the spectacle. Edmund’s expression was one of triumph as he anticipated Meg’s response.

She cast a troubled glance at her new husband, whose brow creased in concern at the threat of revelation contained both in the shimmering fabric and in Edmund’s words. Apart from the Vintner family, Owen, Edmund and I, no other guests in the room had any notion of Meg’s true birth and it was the family’s intention that it should remain that way. Edmund’s gift and his style of presentation had rendered the secret more fragile than ever.

After a pause Meg stepped forward and gathered the material off her brother’s arm, laying it carefully over the stool, from which it hung in liquid folds, pooling on the floor like molten metal. Her gauze veil, secured by a coronet of spring flowers over her fair, profusely curling mane of hair, frothed around her smiling face as she dropped Edmund a graceful curtsy.

‘Thank you, Edmund,’ she said, and stretched up to kiss his cheek. ‘It is a fabric of spectacular beauty – a vision of heaven in fact – and, with your permission, I shall donate it to the Queen of Heaven herself, to fashion a gown for the statue of the Virgin in St Mildred’s church, in gratitude for her blessing on our marriage today.’

Beside me I heard Mette release a long sigh, as if she had been holding her breath. Then her familiar chuckle cut through the tension, which had begun to pervade the room. ‘Saint Nicholas be praised! We have a bride with brains and beauty and will have a shrine to the Virgin to rival any royal benefice. For such a gift the Holy Mother will surely grant this marriage happiness and fertility.’ Applause rippled from the crowd as she turned away, rolling her eyes at me and adding under her breath, ‘That piece of cloth would have bought a new bed and all the hangings – but luckily I have given them that.’

Edmund strolled over to us, bending to place cool lips on Mette’s cheek. ‘Meg does you proud, Madame Mette. Your William is a very lucky man.’

‘They are a happy pair, Edmund,’ she responded emphatically. ‘Long may they remain so!’

2 (#ulink_c892a5a9-b356-554f-8c91-e7e667422add)

Jane (#ulink_c892a5a9-b356-554f-8c91-e7e667422add)

Tŷ Cerrig, Gwynedd, North Wales

THE SOUND OF THE watch-bell always caused a bustle in the house. It meant either trouble or visitors, sometimes both. The cheese-making would have to wait. I took off my apron and sent Mair the dairymaid to discover what all the clanging was about, while I sped out to the brewery to draw a jug of ale. Whoever was arriving, refreshment was bound to be required. By the time I had taken the ale to the hall and set out some cups Mair returned to tell me that three strangers on horseback were trotting up the road from the shore. Strangers were a rarity at Tŷ Cerrig.

‘What is it, Sian? What is happening?’ Face crumpled from sleep, my stepmother appeared through the heavy woollen curtain that divided the solar from the hall, although the word ‘mother’ seemed hardly appropriate for a girl who had seen only three more summers than me; that is to say, seventeen.

‘Strangers arriving,’ I said. ‘I was just going out to see.’

Her face fell. ‘Oh. Must I go and greet them?’

She was pregnant; very pregnant, her belly taut and round, only days from delivery and suffering from swollen ankles and shortness of breath. It would not be good for her to stand in the yard while men and horses milled about and dust flew.

‘No Bethan, you stay in here. Sit down and wait. Whoever it is will come inside eventually. Father will be there by now and I will go out. You can pour the ale.’

Visibly relieved, she waddled to the large wooden armchair that stood by the hearth. ‘Yes. I will do that. I will wait.’

Bethan was sweet but she was a simple soul. Her marriage to my father had taken us all by surprise the previous year, being only eight months after the sudden death of my mother, to whom he had been wed for nearly twenty years and who he had unquestionably loved and respected. But Bethan was an heiress, the only child of a neighbouring landholder. The match had been made and a contract drawn up with a view to securing both her future and ours. It was a sensible arrangement for she had known my father from childhood and trusted him and we all knew her well and understood her disability, brought about by a slow and difficult birth, which both she and her mother had only just survived.

I glanced around the hall to check that it was ready to receive guests. A peat fire smoked lazily in the hearth, beside it an iron cauldron seethed steadily, containing the evening pottage. With regret I calculated that I would have to wring the necks of a couple of chickens if guests were staying, unless they came bearing gifts.

Outside, I had to shade my eyes against the sun which still stood high in the May sky. The warning bell had brought my father Hywel and two of my brothers, Maredudd and Dai, from the sheep pens where they had been checking the month-old lambs before their spring release with the ewes onto the high moorland grazing behind the house. Sheep dogs were yapping at their heels but on curt orders from their masters they dropped to the ground, crouched and silent, as four horses clip-clopped under the farmyard gate-arch. Three of them were mounted, the fourth was a laden sumpter led by the foremost rider.

My father gave a shout of welcome and stepped forward to grab his boot. ‘Ah, glory be to Saint Dewi, it is you Owen Tudor! You are very well come to Tŷ Cerrig.’

The long-legged man who swung down from his horse immediately drew my father into a bear hug and slapped his back heartily. ‘It has been too long, Hywel, but at last I have brought my sons to meet their Welsh kin.’ He turned to the two young men who still sat their horses and switched to English. ‘Edmund, Jasper – get down and greet your cousin Hywel Fychan. You probably do not remember him but I expect he remembers you, eh Hywel?’

He was a good-looking man, this Owen, whose Welsh was fluent but tinged with a foreign lilt. However, the sons who obeyed his command to dismount were of a great deal more interest to me. At first sight they seemed of similar age but judging by the way the darker one took the lead as if by right, the redheaded son was the younger. Both tugged off their felt hats and made respectful bows and while the elder was receiving another of my father’s generous hugs, the gaze of the younger wandered in my direction. I felt an unexpected rush of pleasure as his face creased in a chip-toothed smile. I shyly returned the smile.

‘I remember two small boys who were often up to mischief,’ said my father when the greetings were done. ‘But now I see two young men who may create more.’

Owen laughed heartily. ‘You can say what you like, Hywel, because they will not understand you. I am ashamed to say they have no Welsh. I thought if I brought them here they might learn a few words and something about farming. Only one generation from the land and yet they know nothing!’

‘My boys will see to that,’ declared Hywel, beckoning them forward and switching to English so that Owen’s sons might understand. ‘This dark Welsh ram is Dai and the one with the light hair is Maredudd, my eldest son. He looks like his mother, do you not agree? Sadly she went to the angels at the start of last year.’

‘Agnes is dead?’ echoed Owen, making the sign of the cross. Clearly he had known my mother well for his expression became shadowed with regret. ‘May she rest in peace. I am very sorry to hear that.’

My father frowned fiercely. ‘Yes, it was a great loss. She gave me two daughters and three sons and then died from a fever; who knows why? I have a new wife who is about to give birth so we are praying all will be well with her. Come inside now and meet her. Her name is Bethan. Mind your head.’ He caught sight of me as he ushered his cousin towards the low door of the house. ‘Oh, this is my younger daughter Sian. The elder one is married and lives away now.’

I bobbed a curtsy as they passed me and Owen paused to smile and bow, repeating my name in his mellow voice before ducking under the lintel. The two younger men stopped and greeted me politely. The first followed immediately in his father’s footsteps but the one with the bright hair and the chip-toothed smile lingered before me. ‘Sorry, I did not catch your name. Mine is Jasper.’

Why did I have to blush? Having three brothers I was used to boys and these cousins were surely no different to them? ‘It is Sian,’ I said.

‘Shawn?’ he repeated, inaccurately. ‘Is that a Welsh name?’

‘Yes, I suppose it is. My mother was French and called me Jeanne but everyone here calls me Sian.’

He still looked a little puzzled. ‘Oh I see. So that might be Jane in English? Will you forgive me if I call you Jane?’

I found myself telling him I would; yet even as I said it I knew it was not true. My name sounded harsh and plain in English – but then he endeared himself to me once more by saying, ‘My mother was French too.’

‘Yes, mine was your mother’s companion at one time. I am sure my father will explain it all.’

He nodded and paused to gaze around him. ‘It is very beautiful here. Believe it or not it is my first close-up sight of the sea and I find it quite breathtaking, so wild and empty!’ His grin was apologetic but he turned his face to the land and went on, ‘And I like the way the stone walls make patterns on the hillsides. We rode through the mountains yesterday and they were truly awe-inspiring. I have seen nothing like them in England.’

His enthusiasm for my homeland made me garrulous in return. ‘I am so glad you think that. I do not know how long you will stay but very soon we will be moving the sheep up into the hills. We walk them to the high pastures and sleep out under the stars. Perhaps you might join us?’

Jasper shrugged. ‘My father seems to take it for granted that we will stay for a while but tell me honestly, do you have room for us?’ His gaze swept the facade of the house and he looked doubtful.

Whatever kind of accommodation this Jasper was accustomed to, his question indicated that it was much grander than the sturdy stone farmhouse before us. My grandfather Tudur Fychan had built Tŷ Cerrig in the reign of the fourth King Henry, after English soldiers had run him off his lands during Glyn Dŵr’s rebellion, when half of Wales had risen against the English occupation. On that dreadful occasion they had put his family’s timber-framed house in Ynys Môn to the torch and in due course, when my grandfather Tudur at last managed to establish a new home on land in the foothills of Yr Wyddfa, he proudly called it Tŷ Cerrig – House of Stone – to show that he had built a place that would defy the flames. But it was just two floors: the lower one was a byre and a dairy and the upper floor was where we all lived. All the outbuildings, barns, stables, brewery, kennel and latrine, were made of timber. My father Hywel came back from England with his French wife to take over the family farm when Tudur Fychan died before I was born.

I quickly dismissed Jasper’s doubts. ‘Oh yes, there is plenty of room at this time of year. Now that the cows are out in the fields and the byre is scrubbed clean, the boys sleep downstairs. Fresh straw makes a good pallet.’

He laughed. ‘It is probably considerably cleaner and more comfortable than some places we have lodged in during our journey.’

I gestured through the door, towards the steep ladder-stair that led to the family quarters. ‘Shall we go up? There is refreshment ready.’

He glanced back at the horses. Maredudd and Dai were walking them towards the stable.

I understood his concern for his mount. ‘You do not have to worry. The boys will see to them and bring in your saddlebags.’

He nodded. ‘I am sure they will. I was just remembering that there is a brace of hares in one of the bags. My father did some hunting while we were crossing the high moors yesterday. He is a crack shot with his bow. In this warm weather they will be ready for eating.’

I smiled happily, for this meant the chickens were reprieved and our egg supply preserved. ‘We will roast them this evening,’ I said. ‘I will see to it. You go on in and meet your hostess.’

‘I feel as if I have already met her,’ he said, gazing at me earnestly and making me blush again, ‘and I look forward to the rest of my stay, however long or short it may be.’

I went off to search for the hares with a spring in my step.

* * *

We ate outside in the soft evening light, eleven of us around the long board used for harvest feasting. Even Bethan managed to clamber down the stair and sit with us, smiling happily and saying little but looking bonny in her best blue gown, laced at its loosest. My youngest brother Evan, a cheeky dark imp of eight, had been sent to the neighbouring farm across the valley to bring Bethan’s parents, Emrys and Gwyladus, to meet the three Tudors and we all squeezed onto benches and stools, with the big wooden armchair brought down from the hall and packed with cushions for Bethan. Beyond the farmyard wall the ground sloped towards the west, giving us a fine view over the vast sweep of Tremadog Bay and, in the far distance, the dark humps of the Lleyn Peninsula, Gwynedd’s westernmost arm. As the sun dipped below the hills the sky turned from pink to ochre, gold and red, reflecting off the sea and turning the bay to a fiery crucible. Such long, stunning sunsets were infrequent here and we made the most of it, the men draining a cask of father’s treasured malmsey and talking on well after the last of the pottage had been scraped from the cauldron and the bones of the hares tossed to the dogs.

‘It is a pity that Gwyneth is no longer here with us,’ Hywel said to Owen as I brought baskets of dried fruit and bowls of cream to dip it in – a rare treat, because most of our cream was made into cheese for winter. ‘Perhaps you remember her as an infant, Owen? She was our firstborn and lived with us at Hadham when Queen Catherine was still alive. She married two years ago to a man from Ynys Môn – or do you call it Anglesey now that you are an English gentleman?’

Owen smiled, his teeth showing impressively few gaps. ‘It depends who I am with, Hywel. Did she marry a relative, another descendant of the great Ednyfed Fychan, Steward to the Prince of all Wales?’

My father’s teeth did not make such a fair showing. ‘It would be hard not to in that part of Wales, would it not? She is living in the Tudur family heartland now, taking us back where we would be still, had our fathers not supported Glyn Dŵr.’

‘Oh you are not going to start telling tales about the good old days before the great rebellion are you, my father?’ cried Maredudd, well lubricated by the wine. We were all speaking English, although some were more fluent than others in the language of our conquerors. ‘And give our guests a chance to crow about the Lancastrian victory at Shrewsbury!’

I cringed inwardly. Maredudd was the salt of the earth and as solid as a doorpost but tact was not his strong point. Fifty years ago there had been a battle at Shrewsbury in the Welsh March when the present king’s father had slain the famous knight Hotspur and put an end to a rebellion led by my father’s ancestor Owain Glyn Dŵr, who had subsequently fled to the wilderness of Yr Wyddfa.

Owen’s brow creased alarmingly. ‘Why would my sons crow about a disaster that befell their father’s godfather?’ he cried, flushed and perhaps also a little excited by the rich malmsey. ‘Glyn Dŵr was a great man and a learned one. Not a man to be denigrated in my hearing.’

Edmund selected a dried plum, unperturbed. ‘I fear I know nothing of all that,’ he told Maredudd, dipping the fruit in cream as he spoke. ‘Our tutors taught us only ancient history.’

‘And poetry,’ added Jasper in an apologetic tone. ‘Now if you were to ask us to recite some Virgil one of us might oblige.’ He looked pointedly at Edmund but his brother ignored him, chewing contentedly on his plum, perceiving no need for a tactful change of subject. Jasper clearly did and turned to me to provide it. ‘What were you telling me, cousin Jane, about walking the sheep to the high pasture?’

Before I could answer Maredudd spoke up from the fire, on which he was heaping more windfall branches gathered from the nearby woods. ‘We were hoping to start out tomorrow but perhaps you have changed your mind now, Father?’

Hywel glanced across at him and frowned. ‘No, I have not. We need to start tomorrow to be back in time for Bethan’s baby. We cannot leave any later.’

‘Surely Bethan is not going with you!’ exclaimed Edmund, clearly alarmed at the thought.

I hid a smile behind my hand and my father roared with laughter, while Edmund reddened with chagrin. ‘No, no!’ Hywel exclaimed. ‘Of course not! Do you think we are Irish gypsies to birth our cubs in the bracken? Gwyladus and Emrys will stay here with Bethan and we will not be away more than two or three days. The babe is not due for a sennight yet.’

I glanced at Bethan then, realized she was drooping in her chair and decided I should take her in before she fell asleep. When I stood up I was surprised to see Jasper follow suit.

‘I will light your way, Jane,’ he said, reaching for a lantern.

In the end we had to half carry Bethan between us, so sleepy had she become, and I decided it would be best to move one of the pallets from the byre and lay her down on the floor of the dairy, thinking that if she needed to relieve herself in the night, as she often did in her present condition, she could simply wander outside to the latrine. When I had finished making her comfortable and she had fallen into a deep sleep I found Jasper waiting for me on one of the stone benches built against the front wall of the house, the lantern at his feet casting his honest, open face into mysterious shade. The moon had risen, spreading its pale light across the open expanse of the yard and turning the shadows inky black.

He patted the bench beside him. ‘Please sit with me a while, Jane. Our fathers talk too much of times gone by. I would like to learn about your life here and now. I think Bethan cannot be much help in the house. She seems a little – simple, or am I being unkind?’

I bit my lip. We did not like to discuss Bethan’s condition with strangers but although he had no Welsh and clearly knew nothing of our ways, I discerned a warm heart in Jasper, which gave me confidence in his discretion. After all, however many times removed, we were cousins – family.

I sat down, careful to leave a respectable distance between us. In the moonlight he looked younger, more like one of my brothers than an esquire of the king’s household, which I now knew him to be. ‘No, you are not unkind, sir; you are perceptive. Bethan is simple but she loves my father and shares his bed willingly. It is not her fault that she has no great domestic skills. She cannot cook or make bread or cheese, although she can churn butter if you stop her at the right moment. She cannot recognize one herb from another or remember their properties and she cannot tell a mark from a groat. But when she is not great with child she can weed the vegetable garden, milk the cows and goats, feed the poultry and collect the eggs; she loves to tend the orphaned lambs and calves and if I set it up for her she can turn a spindle for hours.’ I gave him a cheerful smile. ‘So you see she is far from helpless, and there is also Mair who is our dairymaid, who lives in the village by the shore and fetches and carries and makes the pottage.’

The sound of the stream that ran fast-flowing through the wooded vale beside the house filled the silence between us agreeably. The vale and the stone-walled fields surrounding the policies were all bathed in milky moonlight. ‘Our grandfather chose well when he built here,’ I told him. ‘The stream gives us milling-power and clean water, we have wool for weaving, grain to make bread and ale, and fat for lamps and soap. The sheep give us fleeces to sell to the monks, we have fish in the sea, meat on the hoof and crops in the fields. Between us we make most things we need and I keep the accounts and the recipes. Our household works quite well. You will see if you stay a while.’

‘I suspect that it works because you toil from dawn to dusk, Jane. And where and when did you get an education, which you clearly have?’

‘That was due to my mother. She spent her girlhood in a convent and taught us all to read and write and reckon. I am trying to ensure that Evan learns now but it is not easy, especially at this time of year when he is needed on the land. In winter it is easier to keep him at his letters. Our mother intended him for the priesthood but I cannot imagine that happening now. He is bright but not at all bookish.’ I knew I was talking too much but the words just seemed to spill out of me.

Jasper screwed up his face and shook his head in exasperation. ‘I feel I should remember your mother. Her name was Agnes was it not? But tragically I cannot even picture my own. Edmund says he can but if so he does not describe her very well. He makes her sound like a royal doll, which I am sure she was not.’

I felt a stab of pity for him. My memories of my mother were so vivid that sometimes when I was quietly sewing I felt she was sitting at my shoulder. ‘My mother always spoke of yours as an angel. There is no doubt that she was beautiful, whereas mine was like me – I think homely is the word.’

Jasper gave a derisive snort. ‘In my vocabulary homely is a polite word for ugly – and that you are not, Jane! I would say that comely is the proper word – or pretty – certainly attractive! With sweeping eyelashes like yours how could you be anything else?’

I dropped my head, hoping the white glare of moonlight would disguise the sudden colour that rushed to my cheeks. Compliments did not flow freely in our family and my reaction to Jasper’s was involuntary and regrettably rather gauche. ‘Not beautiful anyway,’ I muttered, clenching my hands together in my lap.

He made another dismissive noise. ‘Huh! I do not think beauty always begets beauty, Jane. Look at Edmund and me for instance. He has our father’s bronze good looks, whereas I am blessed with ginger hair and ruddy cheeks. My mother called me Jasper after the dark-red bloodstone in her ring and I imagine she thought the name, like the gemstone, would bring me luck. A younger son always needs luck, does he not?’

With his fresh, freckled complexion and brilliant blue eyes, which even the moon’s glare could not bleach, I wanted to say that he appeared more than comely to me but shyness prevented it. Instead I said, ‘You remember that much about her anyway.’

‘No, I do not remember that; Mette told me.’

‘Who is Mette?’

‘A very bright and forthright lady who knew both our mothers well. She is an old lady now but in some ways you remind me of her.’

Regrettably I have a mercurial temperament and abruptly my mood changed from shyness to indignation. ‘I remind you of a blunt old lady? Well, thank you indeed, sir!’ I stood up and made him a sudden curtsy. ‘Please excuse me, it is time I chased Evan to bed.’

I knew I was being rude to a guest but I could not help myself and left him frowning. Moments later I heard footsteps behind me; his voice in my ear sounded contrite. ‘I said bright, not blunt, Jane! And Mette is probably the woman I admire most in the world.’

It was not until later, curled up sleepless on my pallet by the hearth, that I appreciated the compliment hidden in Jasper’s words.

3 (#ulink_ec05ea3e-e393-5069-bed9-1925c1b6e2a1)

Jasper (#ulink_ec05ea3e-e393-5069-bed9-1925c1b6e2a1)

The Royal Progress; Westminster & Greenwich

SWEET JANE’S BONNY FEATURES were to become a recurring image in my mind throughout the year that followed, particularly those long, sweeping eyelashes shading her deep brown-velvet eyes. Certain memories made particularly vivid returns. In blessedly balmy weather we had shared the rustic delights of shepherding Hywel’s flock of sheep up to the high pastures and the picture of Jane, in a straw hat and long boots, with her skirts tucked up and a shepherd’s crook in her hand, made frequent visitations in my quieter moments. Later, on our return to Tŷ Cerrig, I had witnessed her handling the birth of Bethan’s baby, when she chased all the men out of the house and set about supervising the midwife, cheering the mother and reassuring the grandmother, all with seemingly unruffled efficiency. And meanwhile I managed to pick up a few words of Welsh, at least enough to identify a mab from a merch, which is to say a boy from a girl. I had little experience of females of any age but the sight of this smiling fourteen-year-old merch emerging from the front door of the farmhouse to present her father with his newborn daughter remained with me for months, inspiring comparison with church images of the Madonna and Child.

Walking our horses to the field one day Edmund had been scornful of my friendship with Jane, pointing out to me that a relationship with a Welsh farm-girl, especially one whose grandfather had been outlawed for rebelling against the crown, would not be one to mention at court. ‘Enjoy her company while we are here, Jas, bed her if you will, not that beds seem to abound in this part of the world, but for pity’s sake keep silent on the subject of Jane when we return to Westminster.’

I worried about Edmund’s attitude towards females. He did not seem to have absorbed any of the rules of chivalry drummed into us during the lessons on Arthurian legend, which the king had insisted should be part of our preparation for knighthood and which laid particular stress on respect for women. Edmund was always careful to impress our tutors with his grasp of Latin verse and philosophical texts but his moral code was that of the alehouse.

I angrily rejected his implication that I had lecherous designs on Jane. ‘The only bedding I have done here is strawing down the horses, brother – and for pity’s sake will you please stop calling me Jas!’

‘Temper, temper!’ he cried. ‘What does plain Jane call you then? Rust-head?’

‘No, but I will tell you what she calls you. Pretty boy! You frightened the sheep in your bright red doublet and yellow hose – you should have left them in London.’

‘And you should leave those mud-coloured rags of yours in Wales,’ he retaliated. ‘Along with your Welsh words and your bumpkin shepherdess – Jas!’ He had to dodge under his horse’s neck to avoid my bunched fist.

When we did return to court, however, it was not our clothes or my language which sparked a bout of teasing from our fellow squires but the tanned faces we had acquired after three months in field and saddle, weeks which we had both greatly enjoyed, no matter how much Edmund protested that he had stagnated in the ‘rural backwaters’ as he called West Wales.

But there was no prospect of a return to Wales. Memories of Jane were all I was ever likely to have, for now that Edmund and I had both reached our majority our brother the king often summoned us into his company, significantly more than the other household squires. I suspected that this was due to prompting by Queen Marguerite, who seemed to relish the notion that we were first cousins; her father’s sister, Marie of Anjou, was also our aunt by marriage, being queen to our late mother’s brother, King Charles VII of France.

‘But we cannot make anything of this in the court,’ she warned privately, in what I considered her rather charmingly broken English, ‘because King Henry is still le Roi de France, however successful are the armies of our Uncle Charles in Normandy and Maine.’

It was a moot point. According to the peace treaty that had married our mother to Henry’s father, he was officially king of France as well as England. But his commanders were gradually and ingloriously losing the vast swathes of French territory conquered by the fifth Henry and the peace of the realm was seriously threatened by hordes of displaced soldiers who, having settled in Normandy and Maine with their families, were now forced to flee the invading armies of King Charles and return to England, where many of them roamed the shires, homeless, penniless and desperate, stirring up trouble. This series of military setbacks had also drained the royal coffers and caused a dangerous split in the ranks of the English nobility. Earlier in the year the king’s distant cousin, Richard, Duke of York, who publicly lamented these failures, had been banished from court for bringing an army to London, demanding to be given command of the French wars and named as Henry’s heir.

It was Queen Marguerite who told us that she and the king were going on a Royal Progress and Henry desired that Edmund and I accompany them, not as his household squires but as his brothers. ‘Henry will dispense justice to all the poor people who have been robbed and attacked by these renegades from France,’ she explained.

This was undoubtedly an honour, intended to give us an intimate knowledge of our brother’s duties and beliefs. We were to lodge near the royal apartments and share the private solar.

I learned a great deal during that Progress about the way the king’s justice was dispensed, and discovered the enormous discrepancy between those nobles who were actively involved and compassionate overlords and those who dealt with their tenants at third and fourth hand, often using unscrupulous methods of extracting their rents and revenues.

I also found out a great deal about the king and queen themselves. They treated each other with unfailing courtesy but little apparent affection; the private time we spent with them significantly lacked laughter or casual exchange of the kind I expected between two people who had been joined in matrimony for more than six years. In fact, I felt there was a constant, underlying tension, which puzzled me. Of course love was no prerequisite in a dynastic marriage such as theirs but Henry scarcely seemed to notice that Queen Marguerite was undeniably lovely, with an exotic beauty and a graceful figure that elicited furtive but appreciative glances from most of the young men about court. He refrained from any comment on her dress or appearance unless he thought it too elaborate or excessively extravagant. He himself dressed more like a cleric than monarch despite Marguerite urging him to adopt the bright fabrics and brilliant jewels she considered appropriate to the royal state.

She sought our support in this endeavour. ‘The people expect splendour of their king, do you not think? Edmund – you must agree for you are always á la mode. Perhaps you might advise his grace on what the nobility are wearing? I notice that the hems of the young courtiers’ gowns are getting shorter, their hose is more colourful and their jewellery more lavish but I cannot persuade Henry to adopt this style. He dresses as if every day were Vendredi Saint.’

Nevertheless Henry continued to avoid splendour, even when attending the opulent feasts provided by our hosts during the Progress, all of them anxious to please their sovereign, hopeful of obtaining some reward. These occasions provided opportunities for dancing and masking, when many young male courtiers chose to display their physiques, stretching their hose tightly over their thighs and exposing more leg than would be wise in cold weather. King Henry certainly enjoyed a mask, especially if it was based on a biblical theme but his habit was to retire to his private chamber before the evening entertainment became too boisterous.

Usually and much to Edmund’s vexation, he asked the two of us to retire with him. Henry then chose to drink small ale and talk over the events of the day, such as the judicial cases he had heard at the local assizes or a visit he had made to a religious shrine. As strains of dance music drifted through open windows, Edmund’s feet would start tapping out the rhythm, while he strove to preserve an expression of rapt interest in the king’s discourse. I confess that I was often guilty of this myself and reminded of the countless times our greybeard tutors had droned on about the Rule of St Benedict or the writings of St Gregory while beams of sunshine beckoned us outdoors to the joust or the hunting field.

Henry’s cousin and chief counsellor Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, joined the Progress for its final days during a stay at Reading Abbey. We shared our brother’s evening ale as usual and on this occasion so did the duke, a man well known to us. We had good cause to pay him full attention. As a young man, with less status and influence than he commanded now, Edmund Beaufort had proposed marriage to our mother, the dowager Queen Catherine, but the royal council had vetoed the match. Subsequently he had discovered her clandestine marriage to Owen Tudor but agreed to keep it secret and stand godfather to their first son who was named Edmund in his honour. Ever since then he had proved a staunch friend to us and so his presence that evening was highly significant.

The abbot had surrendered his Great Chamber to royal occupation; a huge vaulted and panelled room in which even King Henry’s substantial travelling bedstead looked like a campaign cot. All the doors and windows were closed and the heat of the summer day lingered stiflingly beyond the dusk so that I longed to loosen my collar and open the front of my doublet, under which my shirt clung to me, damp with sweat. The duke and the king sat in carved oak armchairs in front of the empty hearth, two cushioned stools placed before them.

After we had been invited to sit in the king’s presence it was the duke who spoke first. ‘His grace is grateful for the company you have both afforded him during this Royal Progress. He is much comforted by the unflinching loyalty of his two brothers, to him and to his queen, and he has decided that the time has come to show you his favour.’

At this point King Henry lifted his hand to indicate that he wished to speak and Somerset fell silent. Edmund and I exchanged glances and I spied a gleam in my brother’s eye, which resonated with the increased beat of my heart.

‘My lord of Somerset is right,’ the king began. ‘Lately we have felt the grave responsibilities of monarchy weighing heavily on our shoulders and although we can share some of this with our queen and our loyal officials and councillors, it has occurred to us that you, our beloved brothers, who share our royal blood and show us so clearly the love and loyalty which naturally bind us, should be brought within our close circle and raised to a rank which reflects your true status. Therefore it is our desire and intent to create you, Edmund, Earl of Richmond and you, Jasper, Earl of Pembroke. It is our hope that the necessary arrangements can be made for these honours to be conferred by Christmas so you may be ceremonially installed on the Feast of the Epiphany, when gifts are presented in celebration of those brought by the Magi to the newborn Christ. This will be my gift to you.’

At the end of his speech Henry held out his hands, psalter-width apart and smiled expectantly at us, whereupon both Edmund and I sank to our knees before him. Exerting his seniority as usual, Edmund placed his hands between those of the king and spoke the time-honoured oath of fealty, which every nobleman learned by heart.

‘Sire, I am your liegeman in life and limb and truth and earthly honours, cleaving to you above all men, so help me God and the Holy Dame.’

King Henry leaned forward to accept Edmund’s kiss on his cheek and then turned to me, his hands once more outstretched. I felt them encompass mine, his palms surprisingly dry on my sweat-slicked fingers. The same oath left my lips in a voice that shook with emotion. As I moved to give my brother the kiss of fealty I caught the unmistakable odour of incense clinging to his clothes, pungent evidence of the hours he spent daily, praying in church or shrine.

He rose, obliging us to follow suit and his broad smile was unfamiliar but warm. ‘I feel God’s benison descending to salute our brotherly union,’ he said. ‘I will let his grace of Somerset explain the details of your advancement but I hope you will not neglect to give thanks to our Lord and His Holy Mother for their bountiful blessing; and now I will retire to the abbot’s chapel to seek God’s guidance on tomorrow’s assizes. I am told there may be hanging matters involved. I wish you both good night.’

In the absence of a chamberlain, I strode to the door to open it for him, making the guards on the other side jump in surprise and bring their halberds hastily to vertical in salute. As Henry walked out he already looked lost in his own thoughts, his head bowed over clasped hands, like a monk making his way to the midnight Office. As I closed the door Edmund came up behind me and flung his arm around my shoulders.

‘How is it with you, my lord of Pembroke?’ he cried with undisguised glee. ‘Now we are truly brothers to the king!’

I returned his embrace with equal enthusiasm but a stern Somerset stepped forward, urging caution. ‘Not yet, not yet, young sirs!’ He waved an admonitory finger, his grey beard jutting forcefully. ‘His grace bid me warn you to keep this news to yourselves until the formal announcement is made at court. There are legal documents to prepare and land grants to be drawn up. These will take time but meanwhile you can give thought to your crests and coats of arms. The heralds will be made aware of your impending ennoblement and you can also begin to order your robes and livery from the royal tailor. All are used to keeping such secrets. The king plans to make the announcement at Christmas and belt on your swords at the Tower of London on the Feast of Epiphany, as he told you. Meanwhile I offer you both my hearty good wishes and look forward to welcoming you to the ranks of England’s mighty earls.’

* * *

On our return to Westminster Palace we found we had been allocated quarters close to the king’s private apartments, a move that fuelled a spate of court gossip, whether Henry and Somerset liked it or not. Our new chambers were light and airy, boasting elaborate furnishings and casement windows overlooking the Thames, diamond-glazed instead of merely shuttered. Each had a separate guardrobe with a latrine draining into a moat washed clean by each high tide, a welcome privilege, indicative of very high status. Between these chambers lay an anteroom where attendants and visitors might await admittance. The apartments were on the same floor as those of the king, but the sweeping stone staircase was reserved for his use and we accessed our rooms by a narrower and steeper spiral stair. Queen Marguerite and her ladies were housed in a separate wing of the palace, linked to the king’s apartments by a private gallery, where handpicked and trusted members of the royal guard kept discreet watch, despite little sign that it was a path well trodden.

Behind the closed doors of our new chambers Edmund and I were fitted for our coronets and mantles of state. We had been granted funds to extend our wardrobes and for once I was grateful for Edmund’s familiarity with fabrics and fashions, being woefully ignorant on such matters myself. However, King Henry planned a joust in our honour following our installation, and then the boot – or more accurately in this case the sabaton – would be on the other foot, for it was I and not Edmund who knew the best agents from whom to commission new armour, having made a study of the latest developments in military design. Until this time, as yeoman squires of the king’s household, we had been provided with standard ready-made body-defences and so for me it was a proud day when I stood in a hot, noisy workshop off Cheapside to be measured for my first custom-fitted attire.

Edmund was less enthusiastic. ‘What can it matter whether I have the latest hinges on my helmet’s visor,’ he demanded, ‘as long as I can readily open and close it? My chief concern is the shape of the sabatons. The style of a noble knight is judged by how much of his foot extends through the stirrups when he leans back to aim the lance. I definitely want sabatons with the longest possible points.’

The kneeling armourer paused in the act of measuring Edmund’s calves for greaves. ‘As an earl you are permitted to wear them twice the length of your foot but I must warn you, my lord, that if the points are too long, the foot will not readily be released in the event of a fall from the saddle,’ he cautioned. ‘It is a dangerous fashion.’

‘So fashion can prove deadly if you are dragged by a galloping charger, Edmund,’ I remarked scathingly, adding more seriously, ‘You should heed the man’s advice.’

My brother eyed me scornfully. ‘A knight who expects to fall can expect to lose. Nothing demonstrates cowardice more than stunted sabatons.’

In my opinion, foolish risk-taking in jousting and fighting demonstrated nothing but idiocy, but I recalled it was I, not Edmund, who had been lucky to receive only a chipped tooth as a result of a jousting accident and so in the interests of maintaining good brotherly relations I shrugged and, leaving the armourer to pursue the argument, wandered off to examine my surroundings.

Like most noble English knights we would have the individual pieces of our armour made to our measurements in Germany where they had perfected the steel-rolling process. They would then be fitted and altered as necessary in London workshops like this one. I watched perspiring apprentices scurrying between three forges where the master armourers worked. There was barely a moment of silence as they hammered expertly at the many separate items that formed a knight’s ‘attire’: breastplates and backplates, greaves and gauntlets, cuirasses and vambraces and all manner of joints and swivels, buckles and bracers. The mingling of heat, sweat and noise formed a miasma, which I found exhilarating, stirring images of jousts and tournaments and the heady prospect of action on the battlefield. There were shutters at either end of the premises, which even in this late autumn season stood wide open, allowing what breeze was to be found in the narrow streets of the city to carry away the poisonous fumes from the red-hot forges. I leaned against one of the supporting pillars and admired the skill of the finishers working at benches along the walls as they engraved and stamped distinguishing designs into the metal before polishing it. As a squire I was thoroughly familiar with the order and attachment of one gleaming element to another when I fitted them to a knight’s body and felt a thrill at the thought that soon I would be able to appoint my own squires to perform this onerous task for me.

Christmas that year was held at the Palace of Placentia at Greenwich, whither the court moved en masse two days beforehand, travelling downriver on a convenient morning turn of the high tide. Still officially serving as the king’s Squires of the Body, Edmund and I accompanied King Henry and Queen Marguerite on the royal barge from Westminster, enjoying the thrill of the slide under one of the narrow arches of London Bridge as the water churned through to escape into the wider reaches of the Thames beyond.

King Henry had inherited the palace and park at Greenwich from his uncle, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester five years previously and it was a particular favourite of his, due to the celebrated library his cultured uncle had amassed there. It was Queen Marguerite who had renamed it Placentia for its green and rural setting – though it lay only a few miles downstream. The contrast with Westminster’s tightly packed streets and buildings was magical; an oasis, and like the outgoing tidal waters of the Thames, the queen yearned to escape from the confines of urban life upriver. Besides, hunting was one of the few pastimes Henry and Marguerite had in common and there were great chases to be had in the vast enclosure of Greenwich Park. As the oarsmen made swift work of the long meander around the north bank mudflats, I sniffed the salty tang in the air and prayed that the crisp, calm weather would persist and give us some magnificent Christmas sport.

It was King Henry’s decree that on the Eve of Christ’s birth his court should be unsullied by too much eating, drinking and merrymaking, such as had been common during previous reigns and still persisted in many noble houses. So after a long celebration Mass during the morning, there was a decent meal of three courses accompanied by a limited quantity of wine and small ale, consumed while choristers sang beautiful but plangent psalms, and prayers and Gospel readings were heard. Afterwards a troupe of mummers performed a Nativity play dressed in gorgeous traditional costumes kept in the royal Wardrobe for use on this one night of the year. It took place in candlelight as darkness fell outside and was an unexpectedly moving experience. When the shepherds fell to their knees in awe at the choir of angels, enthralled by their soaring voices and twinkling jewelled wings I felt a surge of nostalgia, recalling nights spent under the stars with Jane Hywel and her brothers while embers from the camp fire rose into the dark sky and my father played his harp and sang stories of ancient Welsh legend.

It was at the conclusion of this play, as the applause died down and a hum of conversation started, that King Henry chose to have his big announcement made to the court. He did not do it himself but, appropriately enough, through the services of his Richmond Herald, who began by sounding his trumpet for silence.

‘My lords, ladies and gentlemen of the king’s court and household, hear your gracious sovereign’s will. In so far as his grace’s uterine brothers, Edmund and Jasper, have gained their majority, it is his royal highness’s desire to recognize their legitimate descent from his beloved and much lamented mother, the right royal Queen Catherine, consort to his glorious and right royal father King Henry the Fifth of England. Therefore the honour of knighthood shall be bestowed on them and in addition the king’s beloved brother Edmund shall be created Earl of Richmond, a royal honour and title held in abeyance since the death of his grace’s uncle John, Duke of Bedford, and the king’s beloved brother Jasper shall be created Earl of Pembroke, a royal honour and title held in abeyance since the death of his grace’s uncle Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester. As blood brothers of the king, they shall be granted precedence over all other nobles of the court save the royal dukes. This is the king’s solemn intent and shall be accomplished with full ceremonial at the Tower of London on the Feast of the Epiphany. Hear ye the will of your sovereign lord Henry the Sixth, King of England, France and Ireland!’

The trumpet sounded again and there followed a pause while people digested the content of the herald’s announcement, and then suddenly our fellow squires surrounded us, clapping us on the back and uttering cries of surprise and congratulation. This tumult was brought to a halt by two royal pages calling for precedence and pushing our friends aside to clear the way for Queen Marguerite, who appeared before us, beautiful in her glittering Christmas array, and favoured us with a smile that almost outshone her jewels.

‘May I add my felicitations to those of your companions? Our court will be much enhanced by the ennoblement of two such worthy gentlemen and his grace the king will greatly appreciate your good counsel and company. But, mes presque-seigneurs, I wish to be first to retain your services as my partners for the first two dances at tomorrow night’s Christmas Ball. I trust there are no ladies of the court to whom you have already pledged yourselves.’

Brilliant though her smile was, it offered no indication that she would give way to any prior pledge we might have made. Queen Marguerite did not bestow the honour of a dance lightly and certainly did not expect it to be refused. Edmund made a swift bow and left her in no doubt. ‘I would be honoured and enchanted to be my queen’s partner,’ he said gallantly. ‘In fact I would walk barefoot over broken glass to take your hand, Madame.’

The queen’s brows rose in surprise. ‘But then you would be in no fit state to dance, sir,’ she said. ‘And the first tune is always a lively one.’

I made my own bow of acquiescence. ‘Then I hope the second may be long and slow, your grace,’ I murmured.

She gave me a quizzical glance. ‘Do you indeed, Master Jasper? Then you had better have a word with the musicians. I look forward to tomorrow, Messires. Again, my congratulations.’

Her damasked cloth-of-gold train swept the floor as she turned away.

4 (#ulink_fed8242f-3790-525f-b819-c12b0a4e4271)

Jasper (#ulink_fed8242f-3790-525f-b819-c12b0a4e4271)

The Palace of Placentia, Greenwich

IGNORING THE SUMPTUARY LAWS – again – Edmund chose to wear a purple doublet for the Christmas Ball although he called it violet.

‘We are royalty,’ he retorted when I questioned this. ‘The king confirmed it last night. We are “in the purple”.’

‘We have not yet been knighted or belted,’ I persisted. ‘You will be considered presumptuous.’

‘Bah! I do not care what people think. The colour suits me and I will wear it. I guarantee the queen will compliment me on my choice.’

To ensure that his appearance attracted even more attention he wore the same yellow hosen that had frightened the sheep in Wales. The belt slung around his hips was set with amethysts and the doublet was trimmed with something that looked suspiciously like sable, which was in the same sartorial category as purple, but Edmund claimed it was marten.

My own appearance was probably unremarkable beside my brother’s but I was pleased with the belt I had found, studded with stones of polished green agate to match my emerald green doublet with cream-panelled sleeves and with my parti-coloured hose of dark red and blue. The barber had trimmed my hair and shaved my cheeks smooth and I had bathed in lavender-scented water for the occasion.

Mellow with food and wine from the feast, I stood aside to observe Edmund lead the queen onto the floor and tried to steady my nerves at the prospect of doing the same in my turn. Judging by her dimpled smiles, Queen Marguerite was delighted with the nimble-footed Edmund, and I feared my ability on the dance floor would not match his, despite much effort on the part of a French dancing master.

However, I forgot these qualms as my attention was drawn to the charming sight of a tiny girl with long dark chestnut hair, which swung as she danced and was held off her perfect little face by a slim gold circlet. I recognized the man she danced with as one of the king’s household knights who rejoiced in the name of Sir John St John but it was the girl who caught my interest. Her pink gown was trimmed with pearls and figured with gold daisies, and the bodice was cut straight across her chest in the fashion ladies adopted to show off the swell of their breasts. But this girl was too young for breasts. She could have been no more than ten years old and I wondered what she was doing at court at such a tender age; then I forgot my curiosity, absorbed in the gracefulness of her dancing. Erect and straight-backed, her small feet seeming barely to touch the floor, she danced the estampie, a lively French dance involving intricate stamping steps as the name implied, that built to a crescendo of energetic jumps and whirls. The girl’s slender body began to sway and leap with supple strength, keeping perfect time as the pace increased, completely at one with the music, smiling all the while, a sweet, secret smile as if delighted with the place it took her to. The girl’s demure presence seemed dominant in the dance; she was always in the right position, yet she seemed unaware of who took her hand or with whom she turned but danced as if she alone were on the floor. Even the queen’s glittering and glamorous figure was outshone. I could not take my eyes off her.

‘Congratulations on your impending ennoblement, Master Jasper; I see you are enjoying my daughter’s dancing.’

I turned in surprise. At first glance the woman who stood beside me appeared to be an adult version of the same girl, except her hair was hidden under a black turban headdress studded with jewels and her gown was a darker pink with old-fashioned trailing sleeves. She stood as slight and straight as her daughter but her face was wrinkled and faintly mottled.

I made her a bow. ‘You have the advantage of me, my lady, in that you know my name.’

‘I am Lady Welles but my daughter’s name is Beaufort, Lady Margaret Beaufort. Her father was the first Duke of Somerset, the present duke’s late brother.’

The music raced to a climax, accompanying my moment of enlightenment. ‘Ah – the Somerset heiress,’ I found myself saying and then wished I had not.

Lady Welles frowned. ‘Indeed. Most men measure her worth by her estates but I thought you had discerned something more. You did not appear to be counting her fortune as you watched her.’

‘She is very young,’ I said, feeling the accursed blush creep up my neck. ‘But even so, yes, there is certainly something remarkable about her.’ The music crashed onto its final chord. It was over, and the dancers made their acknowledgements. I bowed politely again to Lady Welles. ‘Forgive me, my lady, but I am obliged to the queen for the next dance. I hope we meet again.’

Walking away, I cast a last glance at Margaret Beaufort as her partner escorted her from the dance floor. She was not in the least out of breath. Suddenly I wished it was her rather than the queen that I was pledged to dance with, naively believing that so young a girl would not judge me or compare me with my brother. She appeared to be a creature of the air rather than the earth, reminding me of one of the hovering angels illuminating my psalter.

As I had anticipated, the next dance was a slow one. Edmund had performed all the leaps and kicks demanded by the estampie and now I was able to relax into a bass, performed to a largo given by a piper and a solo singer. It began with alternate men and women holding hands and circling in a series of short and long steps first one way then the other, interspersed with graceful individual spins and regular changes of position through the centre, couples forming the spokes of a wheel and turning back and forth. The moves were intricate but the pace was slow, the intention being for the dancers to show off their balance and posture rather than their stamina. Happily there was little opportunity for conversation as we weaved across, around and between each other, passing with smiles and nods, until the dance ended and we found ourselves once more with our partner for a final bow.