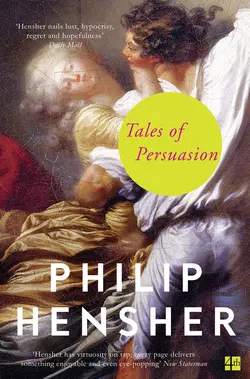

Tales of Persuasion

Philip Hensher

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 612.81 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Ten daring stories from ‘a writer who seems capable of anything’ (Guardian), the Booker Prize-shortlisted Philip HensherBackdrops vary in this collection of stories from the author of The Northern Clemency – from turmoil in Sudan following the death of a politician in a plane crash, to southern India where a Soho hedonist starts to envisage the crump and soar of munitions. Each story, regardless of location, reveals a great writer at the peak of his powers.