King of the Badgers

Philip Hensher

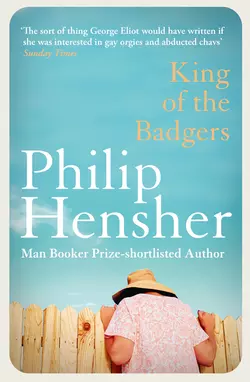

After the success of The Northern Clemency, shortlisted for the 2008 Man Booker Prize, Philip Hensher brings us another slice of contemporary life, this time the peaceful civility and spiralling paranoia of a small English town.After the success of The Mulberry Empire and The Northern Clemency, which was short-listed for the 2008 Man Booker Prize, Philip Hensher brings us the peaceful civility and spiralling paranoia of the small English town of Handsmouth.Usually a quiet and undisturbed place situated on an estuary, Handsmouth becomes the centre of national attention when an eight-year-old girl vanishes. The town fills with journalists and television crews, who latch onto the public's fearful suspicions that the missing girl, the daughter of one of the town's working-class families, was abducted.This tragic event serves to expose the range of segregated existences in the town, as spectrums of class, wealth and lifestyle are blurred in the investigation. Behind Handsmouth's closed doors and pastoral façade the extraordinary individual lives of the community are exposed. The undisclosed passions of a quiet international aid worker are set against his wife, a woman whose astonishing aptitude for intellectual pursuits, such as piano-playing and elaborate cooking, makes her seem a paragon of virtue to the outside world. A recently-widowed old woman tells a story that details her late discovery of sexual gratification. And the Bears - middle-aged, fat, hairy gay men, given to promiscuity and some drug abuse - have a party.As the search for the missing girl elevates, the case enables a self-appointed authority figure to present the case for increased surveillance, and, as old notions of privacy begin to crack, private lives seep into the public well of knowledge.Handsmouth is a powerful study of the vital importance of individuality, the increasingly intrusive hand of political powers and the unyielding strength of Nature against the worst excesses of human behaviour.

KING

OF THE

BADGERS

PHILIP

HENSHER

To

The

Gang:

Bertie

and J.B.

and Sam

and Rita

and Ralf

and Julia

and Yusef

and Jimmy

and Marino

and Renaud

and Richard

and Alan again

and Lapin again

and Professor A

and Dickie Heat-Hot

and not forgetting Nix (Hi Nicola!)

and Mrs Blaikie (with love from Rufus)

and Herbert who said it’s all quite laconic once

but especially and always and once more for my husband

and really just to say to all of them and probably some others too

What

Fun

It’s

All

Been.

CONTENTS

COVER (#u85bb396e-3b48-58bc-ba71-2553c69d33e6)

TITLE PAGE (#u0a3ebd73-d55c-5859-bd1e-001b84d9541a)

DEDICATION (#u47d6ac8d-b365-592e-813b-342b17bbbabe)

BOOK ONE (#ulink_57da363d-188d-5032-9c92-849e8d5f0cae)

NOTHING TO HIDE (#ulink_abaa5545-ad53-5207-bf7f-7f14895c4f21)

CHAPTER 1 (#ulink_aeb0e193-37f5-5fd4-bd8d-b5fa3d57e9b4)

CHAPTER 2 (#ulink_58d6351f-5dba-5c83-aed4-36794bd92023)

CHAPTER 3 (#ulink_34aa65cb-73a3-5700-a8a9-2a501d736b9a)

CHAPTER 4 (#ulink_2fd877b7-2c92-5859-b950-bc91fe8bc85d)

CHAPTER 5 (#ulink_01a8cd89-619a-5538-a216-2a5589c15e3f)

CHAPTER 6 (#ulink_a06a3258-17f3-5939-ab70-4aa6d4505d8d)

CHAPTER 7 (#ulink_532eb68a-c9fb-549c-a33c-73f3d673d5b2)

CHAPTER 8 (#ulink_158ddf71-9572-5419-bee0-35b5d2da9434)

CHAPTER 9 (#ulink_7b3fed08-2490-5512-83a6-07ec88df4c86)

CHAPTER 10 (#ulink_9d1fa114-77a5-557b-8a03-4a5d9ce1f983)

CHAPTER 11 (#ulink_8f8f0751-8c18-58b0-ad38-2aae34a66933)

CHAPTER 12 (#ulink_2630ebc3-e631-5e8b-aa1b-62d57cd99658)

CHAPTER 13 (#ulink_a1b37fc3-ac7a-5f62-9f73-5841a6e98109)

CHAPTER 14 (#ulink_841dc3ff-f03e-592e-a4cf-ca990eb608e3)

CHAPTER 15 (#ulink_c96f628a-ebff-5260-b390-8bc01a57056f)

CHAPTER 16 (#ulink_8a52ebbc-d915-535c-a80d-35bb6cab9e7b)

CHAPTER 17 (#ulink_2978ee44-173d-571c-bb9e-ab9807a23e4b)

CHAPTER 18 (#ulink_5e3bc602-c01b-52bd-b8c8-6a414a881831)

CHAPTER 19 (#ulink_ab0cfc9a-fa73-56ca-aff8-406f22ef033c)

CHAPTER 20 (#ulink_7e09c228-5aa7-53c3-9ec0-51208abc2123)

CHAPTER 21 (#ulink_fff5c1c7-c1a1-54fc-8598-dd61371ce377)

CHAPTER 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

FIRST IMPROMPTU (#litres_trial_promo)

THE OMNISCIENT NARRATOR SPEAKS

BOOK TWO (#litres_trial_promo)

THE KING OF THE BADGERS (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 1 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 2 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 3 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 4 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 5 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

SECOND IMPROMPTU (#litres_trial_promo)

TWO HUNDRED DAYS

BOOK THREE (#litres_trial_promo)

NOTHING TO FEAR (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 1 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 2 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 3 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 4 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 5 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (#litres_trial_promo)

PRAISE (#litres_trial_promo)

OTHER WORKS (#litres_trial_promo)

CREDITS (#litres_trial_promo)

COPYRIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER (#litres_trial_promo)

BOOK ONE (#ulink_1a4b8d59-636b-5c9a-82aa-ac3fb7be412e)

NOTHING TO HIDE (#ulink_30ddaeeb-17a4-5c03-a5f0-ab592f3f8eff)

That bowler-hatted major, his face is twitching,

He’s been in captivity too long.

He needs a new war and a tank in the desert.

The fat legs of the typists are getting ready

For the boys and the babies. At the back of my mind

An ant stands up and defies a steam-roller.

GAVIN EWART, ‘Serious Matters’

1. (#ulink_5dc7708f-c9b9-5a49-8ff9-e14389b5dc97)

Last year, at the hot end of spring, in the small town of Hanmouth on the Hain estuary, a rowing boat floated in the middle of the muddy stream. Its stern pointed inland, where the guilty huddle in cities, its prow towards the ocean, five miles down the steady current. There, all our sins, at the end of all the days and weeks, will be washed away. The boatman dipped his oars deep. There was something thoughtful in the repeated movement. The current was running quickly, and his instructions were to keep the boat where it lay, in the centre of the slow flood, the colour of beer and milk.

‘Most of my customers,’ he said to his single passenger, ‘want to go to the same place. They want to be rowed across the estuary to the pub.’

‘What pub would that be, then?’ his passenger said, with a touch of irritation. He was a man fat in rolls about the middle, the top of his bald head wet and beaded. His gingery-white hair shocked out to either side, weeks away from a respectable haircut. A life of taxis, expense-account drink, and hot greasy lunches had marked him. Bachelor; or divorced more like; let themselves go in the circumstances.

‘It’s the Loose Cannon,’ the boatman said. ‘It’s over there, behind you. You can see the lights. On the spit of land where the river Loose meets the Hain estuary. It’s a joke, a sort of joke, the name of it.’

The man did not turn round to look. Never been in a boat before. Thinks he can drown in two yards deep. His right hand gripped the boat; the left was on the camera about his neck. At his feet, a black case, halfway between a briefcase and a suitcase in size, was laid carefully flat.

‘Easier to get there this way,’ the boatman went on, between his strokes. ‘At the end of the spit. Between the estuary and the Loose. Car park’s near a mile off. Easier to get me to row them across from Hanmouth jetty.’

‘Nice pub, is it?’ his passenger said. Taking an interest at last.

‘Old pub,’ the boatman said. ‘Very. Just that and the lock-keeper’s house over there. Not called the Loose Cannon properly. Someone’s joke. On the licence, it’s the Cannons of Devonshire. Been called the Loose Cannon as long as anyone knows. As long as I’ve been here. Because of the river, there, the one joining the estuary.’

On the ramshackle jetty, ten feet long, the girl with the cropped hair stood where they had left her. Two more heavy cases were at her feet. In the mid-evening light, her features were indistinct. She was an outlined shape, a black silhouette in the deepening blue, a watching upright shadow.

‘You want to go there?’ the boatman asked.

‘?’

‘To the pub. To the Loose Cannon. Most of my customers—I go back and forth like a shuttle in a loom, most of the summer.’

‘No.’

‘There’s nowhere else to go, if you’re crossing the estuary.’

The passenger gave the boatman a brief, city, impatient look. ‘Just what I asked for,’ he said. ‘I want you to row out into the middle of the estuary and keep the boat as steady as you can for twenty minutes while I take some photographs. That’s all.’

‘You’d get some nice snaps from the Loose Cannon lawn,’ the boatman said.

‘Wrong angle. Too high.’

‘That’s a lot of trouble to go to just to get a nice holiday snap or two,’ the boatman said.

The passenger said nothing. The boatman paused, and let the boat float a little downstream, swinging as it went. This was the time of day he most admired. A daylight wash at one end of the sky, behind the far hills, and at the other, the beginning of a warm blue night. The moon was like a fingernail paring, hung above the church, flat on its back. In the half-light, the blossom of the fruit trees in the gardens shone out; the stiff little white flowers on the horse-chestnuts in the churchyard were like bright candles; over a wall, a white-flowering clematis poured and mounted like whipped cream. The disorganized up and down of the town’s gables, house-ends, extensions and rooftops started to be punctuated by the lighting of windows. Here and there curtains were being drawn. The lights of a town like Hanmouth shone out across water for miles at night.

‘Busy this time of year anyway,’ the boatman said. ‘Always busy. People like to come out for the day. For an afternoon. For an evening. Very historic town. Third most picturesque town in Devon, it won, four years back. Don’t know who decides these things. Thomas Hardy came here for a holiday as a boy. You know who Thomas Hardy was?’

‘Yes,’ the passenger said. ‘We did him for O level. I got a B. You’re not from round here.’

‘No,’ the boatman said. ‘You never lose a Yorkshire accent. I’ve been here twenty years. Won’t start saying “my lover” to strangers now. And before that on holiday, every year, since I was a boy, almost.’

‘Like Thomas Hardy.’

‘Like Thomas Hardy. I worked for a steel firm in the north, thirty years. Got laid off. Firm went under. Got a good pay-off first, though. I was a manager. Good job. They said they’d see me all right. Madam says, “Let’s move somewhere we want to live. Hanmouth, that’s the place we want to be.” She was the one who loved it, really loved it. “You can do anything,” she said, “turn your hand to anything. Lot of old people in Hanmouth, very glad to have someone change a light bulb for a couple of pound.” She died five years later. Cancer. Very sudden. Never get over something like that. She wanted to be buried in the churchyard, but they don’t bury anyone there any more. She’s in the city cemetery, like everyone else who’s dead. Still go to pay my respects, every Saturday. Is that so strange?’

‘Just here,’ the passenger said. He opened the camera case hanging from his neck. It was a bulky black object, with a black hole where the lens should have been; not like the pocket-sized silver digital jobs people had these days. The boatman pressed against the seaward current and, fifty feet out in the estuary, they were as steady as a rooted waterweed.

The photographer bent down cautiously, and opened the case at his feet. The boatman could smell his perspiration. In the case, there were three lenses, each resting in a carved-out hollow, and there were other devices the boatman could not have named, each in its specific and bespoke place in the charcoal-coloured foam. The photographer lifted the middle-sized lens out, shutting the case with the same care, not making any sudden moves. It was as if there were some unappeased and hungry beast in the boat with them.

‘I’m seventy now,’ the boatman said. ‘You wouldn’t think it, people tell me. This keeps me fit.’ It was true: his wiry arms had lost flesh, but still pulled firmly; his heart, he considered, beat slowly in his narrow chest. He had kept his hair close-shaven in a way that chimed with the way some young people kept it, though it was white now. ‘There was a boatman before me, there was always a boatman. Running them as wanted from Hanmouth pier to the Loose Cannon. The old one, he’d taken it over from his father, forty years back. Had sons, they weren’t interested. One’s a lawyer in Bristol. Not a full-time job any more, ferryman. Hadn’t been for years. I took it on. Keeps me active.’

‘You must know everyone in town,’ the photographer said.

‘Strange lot of people in Hanmouth this week. Don’t know them, never seen a one of them before. Never seen it so crowded. That little girl. I don’t know what they think they’ll see, though. Won’t see her. She’s missing.’

‘Human curiosity,’ the passenger said. ‘There’s no decent limit to it.’ He raised his camera, and quickly, with a series of heavy crunches, fired off some photographs.

‘Five pounds over, eight there and back,’ the boatman said. ‘Could have put up the fare this week, I dare say.’

‘I thought we agreed a price,’ the passenger said. ‘You said thirty.’

‘There and back in ten minutes is eight pounds,’ the boatman said. ‘To the middle and stay there as long as I say is thirty. Have you got permission from Mr Calvin to be taking photographs?’

‘We agreed a price,’ the passenger said.

‘Oh, yes,’ the boatman said. ‘We agreed a price. I can’t do you a receipt, though.’

‘That’s all right,’ the passenger said. ‘I can write my own receipt. There’s no law that says people need permission to take a photograph of a town. Whatever your Mr Calvin says.’

The boatman lifted his oars and kept them in the air; in a second the boat drifted ten feet seawards.

‘Keep the boat where it was, please,’ the passenger said.

‘Mr Calvin, he’s keeping a register of all the press photographers. A lot of them. A hell of a lot. Keeps it nice and tidy, Mr Calvin says. Shame about that little girl.’

‘Did you know her?’

‘No,’ the boatman said. ‘I don’t know as I even recognized her when I saw her face in the papers. There’s twenty thousand live in Hanmouth and surroundings. You don’t know everyone.’

He pulled hard at the oars, keeping the boat steady and parallel to the shore. They’d been out twenty minutes, he saw. Over half an hour and he’d start charging an extra pound a minute; it wasn’t this bugger’s money he’d be paying with. He kept an eye on his watch, worn on the inside of his wrist in good maritime fashion.

‘Of course,’ he said. ‘There’s those who won’t pay the five pounds. If they run off, I don’t chase after them. I phone Mike at the Loose Cannon and he takes the fare out of their change. Not much they can say to that. One lad says to me, last summer, “Five pounds? It’s only over there. I can walk that.” Thinking about low tide, he was. The estuary at low tide, I can’t row across, but they can’t wade across, neither. “No thanks, it’s not deep, we’ll walk across, doesn’t look like much.” I said, “Fair enough.” Fifteen yards out, he were up to his thighs in mud, couldn’t go forward, couldn’t go back. The estuary, it’s got its own mind. It shrinks and it quivers. The ducks walk on it; they’ve got webbed feet. He was in his trainers. I was in the window of the Flask, watching him. Come out and chucked him a ladder in the end. Went out making a hell of a din. Come back quiet as church mice. They only do that once. This town needs me.’

In the rich riverine gloom, the photographer held the machine to his face, and fired off more shots, taking no account of the boatman’s story. From here, there was a low and extensive view of the Hanmouth estuary front, the lights in the windows shut off against the night. At the jetty, the crop-haired girl had sat down, her knees raised. Her thin body in its tight boyish denim made a geometrical figure. A half-illuminated line of smoke rose from a concealed cigarette beneath the raised knees.

The boatman pulled against the current, and the boat held quite straight. On the jetty, another figure had joined the photographer’s assistant. He was talking softly to her. The low voice travelled across the water, and from the sound of it and the narrow-shouldered shape of the man, the boatman recognized Mr Calvin. He’d have something to say to a press photographer who hadn’t made himself known.

‘This for a newspaper, then?’ the boatman said.

‘Something like that,’ the passenger said, continuing to photograph.

‘It’s been five days,’ the boatman said. ‘We’ve been under siege, it’s been like. Everyone being asked, all the time, have you seen the little girl, do you know her mum, what do you know about her dad. Just to go to the butcher’s or the bank. I said to one, “If I knew anything, I’d go to the police, I wouldn’t be telling you.” And you can get photographs of Hanmouth anywhere, on the Internet, lovely sunny day. You won’t get much in this light, I wouldn’t have thought.’

On the jetty, the small figure of indeterminate sex waved largely, as if she had a full-sized flag at a jamboree. Calvin, if that was who it had been, had gone. The swans and geese, misled by the wave, checked their paths and swam towards her. They were spoilt by feeders here, and took movement for the promise of generosity.

‘That’s enough,’ the passenger said. ‘Take me back.’

‘I can take you over to the Loose Cannon,’ the boatman said. ‘There’s no more to pay.’

‘We’ll be fine,’ the passenger said, and though they seemed to be facing in the correct direction, the boat swung round in the stream, pulled by one oar, in a full circle, facing in turn the city and the roar of the motorway over the estuary, the remote blue hills where the sun was setting, and then seawards, where everything goes in the end. And on the jetty, the small figure knelt, opening up a black-backed computer, the blue light of the screen illuminating what, after all, was the cropped hair and small face of a pretty girl, intent on her digital task.

2. (#ulink_d89169ac-666a-587a-8b85-060bbe150bb2)

Hanmouth, that well-known town on the Hain estuary on the north coast of Devon, formed a stratified appearance whichever way you looked at it. The four streets of the place ran between and parallel to the railway line to the coast and the estuary itself. Less stately thoroughfares—alleyways, gennels, cut-throughs, setback squares of white-painted nineteenth-century almshouses and 1930s suburban ‘closes’ with front gardens made out of a bare foot or two of leftover land—squiggled more liberally across the four vertical and distinguished avenues. The first of those verticals ran seamlessly from Ferry Road in the north to the Strand in the south, knotting around the quay and rising to three historic pubs, a plaque commemorating the birthplace of a centuries-dead attorney general and, at its most expensive, unfettered views of the estuary and the hills beyond, crested with a remote and ducal folly-tower. On this first street lived newsreaders, property magnates, people who had made their money in computers and telecommunications. The first house in Hanmouth to sell for a million pounds was here, and pointed out by the innocent locals; but that had been seven years ago, and the figure was losing its lustre, and had long lost its uniqueness. The pinnacle of envy for miles around, for half a county, the Strand in the south was a series of Dutch-gabled houses, pink, cream, terracotta-red-fronted, and everyone, it was said, lived there, meaning that everyone, of course, did not.

Only an odd few lived in the second avenue, the shopping street; the Brigadier and his wife in a wide, flat, shallow eighteenth-century one-house terrace of brick, facing the wrong direction as if it had turned its back on the commerce. The Fore street was holding up well; the community centre, built in municipal interbellum brick, was celebrating its eightieth birthday next year with a Hanmouth Players production of The Royal Hunt of the Sun, among other things. Outside the community centre was a bronze statue of a boy fishing on his haunches, with an elbow on either knee and an expression of great concentration. The statue had been commissioned for the hall’s fiftieth anniversary, which had coincided with the Queen’s silver jubilee in 1977. It had been unveiled at the height of a street party, trestle tables snaking down the whole length of the Fore street, and was instantly and universally known, even in the hand-printed guide to Hanmouth the second-hand bookshop sold, as the Crapping Juvenile. As for the rest of the Fore street: the new Tesco out of town had had no effect on the excellent butcher, the fair-to-middling greengrocer. Had no power, either, over the knick-knack shops, the amateur jewellers making a go of it, or the Oriental emporium run by the two retired sisters, stocked by bi-annual trips to the markets of south India; they returned from Madurai with triumphant rolls of bright silk, hand-made soap, and encrusted, elaborate, tarnished silver trinket boxes to be sold at twelve times the purchase price.

On the other side of the Fore street, as the railway line grew more apparent, the bohemians, the aspiring many who had escaped only so far from Barnstaple, lived in polite and tidy houses, designed for eighteenth-century churchwardens or pre-war shopkeepers. Here, their view was of their neighbours’ windows, principally. In the town, there was one school, supposed to be very good, one fortnightly French-style market, twelve antiques shops and a junk market, a fishmonger with an almost daily van and seven churches, ranging from those that turned to the east during the Creed with hats on, to one that frankly and openly prostrated itself before spiritual emanations, this last in a converted bike shed with a corrugated-iron roof. Miranda Kenyon, who taught at the university and lived in a Dutch house on the Strand, often announced that she had promised herself she would go into that last, mad church one of these Sundays.

That was the part of Hanmouth people thought of when they aspired to live there. It was the part that pronounced their town Hammuth. The bright upward side of leisurely high-fronted Dutch houses, their glass-punctured façades big and shining with the sun setting over the westward hills, its inhabitants pouring a first drink of the evening behind leaded, curving windows, occupying themselves by counting the long-legged wading birds in the shining estuary. They thought of the square Protestant whitewashed houses in the streets behind, or at worst the Edwardian villas further back, towards the railway line. The railway, bearing only the trundling little train to the coastal stretch around Heycombe, was charming in final effect, rather than a noisy interruption of Hanmouth’s postcard qualities. The flowerbeds at the station were well kept, with ‘HANMOUTH’ in topiary, and a level crossing at which widows with woven wicker shopping baskets lined in gingham always seemed to be waiting patiently. A couple of hundred yards down from the station, a white wicket gate and a footpath across the track showed that this was a rare surviving branch line of the sort that was supposed to have been eradicated decades ago. It was quite charming, and harmless.

The people of Hanmouth were conscious of their pleasant, attractive, functioning little town, and they protected it. A police station with a square blue lamp and a miniature fire station added to the miniaturized, clockwork impression. Its one nuisance was represented by the twelve pubs of the town; there was a sport among the students of the university to embark on the Hanmouth Twelve, a mammoth holiday pub-crawl, which sometimes ended with drunken manly widdling off the jetty, as gay Sam put it, late-night vomit on the station platform to greet you with your early-morning train, and once, a smashed window in the florist’s shop at the quay end of the Fore street. These small-town irritations, the responsibility of outsiders, were talked over in the newsagent’s and in the streets. Mr Calvin, to everyone’s approval, took the sort of initiative only newcomers were likely to take, and formed a Neighbourhood Watch. There was some nervous joshing that you’d have to join in a prayer circle before the meetings got going, but in the end they’d been a great success, as everyone agreed. In the last couple of years, security cameras had been put up over the station in both directions, and at the quay where people waited for buses into Barnstaple. Then a little more lobbying secured six more, and as John Calvin said he had explained to Neighbourhood Watch, and Neighbourhood Watch would explain in turn to everyone they knew, now you could walk from one end of the Fore street to the other at any time of the day or night without fear, watched by CCTV. Even quite old ladies knew to say ‘CCTV’ now. ‘You’ve got nothing to fear if you’ve done nothing wrong,’ John Calvin said. ‘Nothing to hide: nothing to fear,’ he added, quoting a government slogan of the day, and in the open-faced and street-fronting houses of Hanmouth, often wanting to boast about the elegant opulence of their private lives, the rich of Hanmouth tended to agree.

The security and handsomeness of the estuary town drew outsiders. It also, less admirably, persuaded those outside its historic boundaries to appropriate its name. Some way up the A-road towards more urban settlements, there were lines of yellow-brick suburban houses, a golf club, a vast pub on a roundabout offering Carvery Meals to the passing traffic on a board outside. In its car park feral children romped, and, fuelled on brought-out Cokes and glowing orangeades, ran up and over the pedestrian bridge across the A-road. They had been known to shy a half-brick at lorries passing below. There was an extensive and spreading council estate on either side of the traffic artery, surrounding the Hanmouth Rugby Club grounds; it provided a flushed and awkward audience to the field’s gentlemanly battles, over a leather egg, mounted for an afternoon, a drama bounded between two dementedly outsized aspirates.

All these things, encouraged in the first instance by estate agents, had taken to calling themselves Hanmouth too. They, however, called it Han-mouth, to Hanmouth’s formal scorn and comedy. It was one of Miranda Kenyon’s conversational set-pieces, the speculating about where the boundaries of Hanmouth would end. On the whole, Hanmouth thought little of the despoiling and misspeaking suburbs that surrounded it and had taken on its name. Though they poured right up to the gates of Hanmouth, they were obviously the city’s, Barnstaple’s, suburbs, not Hanmouth’s. Hanmouth could never have suburbs.

In these suburbs and estates, men washed their cars on a Sunday morning; kitchens faced the front, the better for wives doing the washing-up to watch the events in the street; children kicked footballs against the side of parked cars until bawled out; support for local or national football teams was made evident in displayed scarves, emblems stuck in windows, flags flown from the back of cars; and, at seven thirty or eight o’clock on weekdays, a ghostly unanimous chorus of the theme tune to a London soap opera floated through the open windows of the entire suburb. There was no reason to go there, and Hanmouth knew nothing much of these hundred streets. It was in the early summer of 2008 that an event in these suburbs, whatever settlement they could be said to belong to, rose up and attached itself to Hanmouth, and could not be detached.

3. (#ulink_b6c879ce-f24d-5e4e-ab37-533c8bb73bdf)

No one in Hanmouth proper had ever heard of Heidi O’Connor. Unless she cut their hair, and then they still wouldn’t know her surname. She did her shopping where no one hailed each other or equably compared purchases, in the Tesco’s on the ring-road. She was not one for going to the pub for social reasons or any other, even to the roadhouse on the Hanmouth roundabout. She would have said she found it ‘common’, a word most of Hanmouth would have been astonished to discover a Heidi O’Connor knew or attached any particular meaning to. She had four children, Hannah, China, Harvey and Archie, from nine down to eighteen months. She lived with Michael Thomas, a moon-faced reprobate seven years younger than her. The four children, two with a version of Heidi’s white-blonde hair, two with a dark, thick, doglike scrub on top, were said to get on with their ‘stepfather’, as Micky Thomas generously termed himself when events made a definition necessary. He was the third such ‘stepfather’ the children had known and the eldest two could remember. Only Hannah could remember, or said she could, her proper father and China’s.

With four children at twenty-seven, Heidi’s existence had its circumscribed aspects. She rarely went into Barnstaple—the opening of a new shopping centre represented an unusual outing. She and Micky and the four kids, walking up and down the glass-covered streets of the mall where municipal jugglers and publicly funded elastic-rope artists played with the air for one afternoon only. Here and there, Heidi and Micky said to each other that it was nothing special, really, letting the kids run in and out of the shops. Barnstaple, in general, was Micky’s territory. He went in every Friday and Saturday night; he stayed out till three or four, returning huge-eyed and off his face, as he would say the next day. Saturday afternoons he spent in Hanmouth’s pubs, often drinking until it was time to pick up Heidi from the salon. He waited outside on the pavement for her; he’d had to be spoken to sharply about coming in and wandering about before half five, picking up bottles of conditioner and tongs and putting them down again. He was a familiar figure in Old Hanmouth, as he called it; he was a well-known figure at the edges of the dance floors of the little nightclubs of Barnstaple, his moon face expressionless under a CCTV-defying baseball cap. He would often sell you a little bit of this, a little bit of that.

Heidi thought herself too old for that sort of thing. She spent most of her time indoors when she wasn’t working at the hair salon in Hanmouth, where most of the customers were over seventy, but all right, really. She’d always said at school she wanted to be a hairdresser, and though Hannah and China coming unexpectedly had interrupted the HND, she’d made an effort, bettered herself, finished her course when she was twenty-two, and got a job here, where she worked now. Her dream was to open up a salon of her own, she said; maybe even in Hanmouth. It could do with some competition, something a bit more up-to-date. A bit less blue-rinse, she would say, though she hadn’t done a blue rinse in her life, only heard of them on comedy sketches. ‘I don’t know how she stands them,’ Micky would say to his mates and his associates when Heidi was in the kitchen, talking about the widows and retired woman civil servants of Hanmouth. ‘Them old punters. Smelling of wee and asking for your blue-rinse perm.’ Heidi herself didn’t mind them, or Hanmouth. She didn’t think too much about it. The pay could have been better, but the tips were generous, and it got her out of the house. Micky made money in his own ways. Those own ways came and went, but were a useful backup at any rate. And every Wednesday and Saturday they played the lottery. If you asked them what their ambitions were, they would both have said that they aimed at a future where an exponentially large sum of money landed on them, unearned and undeserved, and proved inexhaustible, however long the pair of them lived. It was sweet that they didn’t seem to think, for the moment, of a future where undeserved and enormous money would rid them one of the other.

Her childhood sweetheart she’d never married, though he’d given her Hannah and China, and he might be in London by now. Harvey’s dad was the one she’d married, and never again. At the end, in the middle of one of those staircase-shaking rows, he’d said he was going to emigrate, to Australia or Canada, and had gone on saying it, with varying degrees of calmness or rage, until one day he’d just disappeared, never to be seen again. (Heidi supposed she was still married to him, all things being considered.) His name was Marcus. She remembered what he looked like, but what had really remained with her from that marriage was Harvey, of course, and Marcus’s half-sister Ruth—they’d had the same father, but Marcus’s mother had been from Bristol, Ruth’s from Barnstaple. The father was where they’d got the black half from. There were fifteen years between Marcus and Heidi, thirteen between Marcus and Ruth. Ruth had always been the same stern-looking girl with cropped hair touched with grey, though she was only two years older than Heidi. At the wedding, with Hannah only just old enough to be a little bridesmaid in peach, China still a baby in Heidi’s mother’s arms with a terrible rash across her face, Ruth’s constant frown hardly cracked. Some old uncle of Heidi’s with a red carnation in the buttonhole of his grey suit and the red-veined nose all Irish drinkers got in the end had leant over to Heidi’s mother and said he was a handsome lad, but he, he was old-fashioned, he supposed, and thought it a shame, his lovely niece who could have had her pick marrying a half-caste like that. And Ruth had abruptly turned round—people said, ‘So she turned round and said,’ but Ruth really had turned round, as swift as a whip in flight—and said, ‘That’s my fucking brother you’re talking about, you stupid old cunt. His name’s Marcus.’ There was no answer to that. The old uncle, who had only been invited because Heidi’s mother was soft-hearted, mumbled something about no offence being meant, nothing personal, because he was an old man and set in his ways and could see she was half-caste too and nothing wrong with that. Mixed race; Heidi knew you didn’t say ‘half-caste’ any more, thanks to Ruth.

Because after the wedding, the three honeymoonless months which ended when Ruth told her that Marcus was screwing the sister of some garage workmate of his, Marcus walked out. Whether he went to Canada or Australia or, Ruth thought, probably only back to his mother’s house in Bristol, Heidi was left not just with a bump, which turned out to be Harvey, but also with Ruth. Ruth always knew what to do. A year ago, she had told Heidi that she ought to ask the salon for a rise in her wages; Heidi had asked, and she’d got it. Ruth knew about child benefit and housing benefit. She knew where it was best to say Micky lived. Once, in Tesco’s car park, a posh woman had left the boot of her car open with all her shopping in it while she went to return the trolley. Ruth, without saying anything at all, had just calmly removed three of her bags from her boot to Heidi’s, had rearranged what was left, and passed the time of day with the silly cow before getting in and driving off. A chicken, two big tubs of ice cream, loads of other stuff. Ruth always knew what to do. Heidi hadn’t been left with much after Marcus did a bunk, apart from a pregnancy she hadn’t wanted or recognized and which might have precipitated his departure— ‘You want to take a look at yourself,’ had been one of his parting shots, pointing at her fattening belly. In retrospect, spending five thousand pounds on a wedding which hadn’t been made of good solid stuff that would last wasn’t the most sensible thing. But she’d been left with Ruth, who was a good thing to be left with. She was worth it.

That Monday afternoon was Heidi’s day off from the salon, and she’d gone round to her sister-in-law Ruth’s house. Ruth’s mother Karen was there too, visiting from Barnstaple. Sometimes she asked Heidi to do something with her hair, and Heidi reverted from her professional discretion to her schoolgirl hairdressing fantasy, mucking about with Karen’s hair, giving it odd colours and streaks, piling it up asymmetrically for the fun of it, and Ruth joined in too, giving her mother’s hair the odd poke. That Monday, though, it was too hot to do anything much, and they’d started off in the back garden, until Karen had said it was too hot for her—it was the sort of day you liked when you thought about it afterwards—and they’d gone inside. They had put the telly on, and watched one thing after another, Property Deals, Money in the Cupboard, Do or Dare, Cash Cow, for a good four hours. At some point, Ruth brought out a little spliff, and they had quite a nice time, just passing it round. Then, at the end of Cash Cow, Ruth had brought out another one, and they’d smoked that. This had happened before; it was a sort of Monday-afternoon tradition, sometimes going with the mucking-up of Karen’s hair, sometimes just with the telly. Sometimes it was just between Ruth and Heidi, sometimes including Karen as well—she wasn’t some old granny type. Because of Heidi having Mondays off, it seemed like the end of the weekend, which could begin on a Thursday night, too, if it seemed like a good idea. Because of the spliff, and because of the sun shining into Ruth’s front room and onto the screen, they’d drawn the curtains. They’d stayed drawn against the street outside.

Micky wasn’t around that afternoon. He’d gone into Barnstaple to the main library. He wanted to become a member to take out books and DVDs, and he’d made an appointment. They’d told him it wasn’t necessary, but Micky liked to know people were going to be there when he was, and he told them he’d not been interested that much at school, but now he wanted to develop his reading skills. The library had fallen over themselves to make an appointment for him to show him round and talk through, they said, his needs. Later, Heidi said she supposed people weren’t as ready as they used to be to join a library—she knew old folk liked their Shakespeare and that. They’d treat you like royalty if you showed any interest.

Little Archie was asleep upstairs on Ruth’s spare bed. The other kids had come home from school—Hannah and China collected Harvey from his infant’s school, next door to theirs, and Hannah could let herself in and make them something to eat. It was quite normal; it happened like that every day, because Heidi was either working at the salon, or at Ruth’s. Micky was either there or he wasn’t.

Around five thirty they looked up from The Adam Riley Show—he was talking to Jude Vakilzadeh off I Want To Live For Ever. She was showing her new collection of pillowcases, duvet covers and sheets, Heidi later recalled with some exactness. One of the kids was there. At first she’d thought, muzzily, that it was China, but it wasn’t. It was Hannah. She had come in through the back, which was hardly ever locked, and stood in the doorway, holding her own hands, one in each.

‘I won’t be long,’ Heidi said. ‘Put something in the oven. I’ll be back home at six.’ The children were supposed to know they weren’t to bother her on her afternoons off, but any old worry, any crisis no matter how small—a missing cowboy hat of Harvey’s, there weren’t any chocolate biscuits, China had hit Hannah—would bring one of them over the road, usually in tears.

Hannah wasn’t in tears. ‘China hasn’t come back from the shops,’ she said. ‘I don’t know where she’s gone.’ Glum and slow with skunk though Heidi, Ruth and Karen were, they all agreed that was what Hannah had said. Karen thought she’d said, ‘And I’m scared,’ as well. That was probably just her picturesque addition to what Hannah had said, a fat little figure standing in the sun-strewn fog, making clutching gestures. In the corner of Ruth’s front room in the sugary smoke, standing up against the purple-paisley dado strip, Hannah made an unconventional harbinger of catastrophe.

‘She’ll be back home before long,’ Heidi said. ‘I’ll be over soon.’

But Hannah had insisted. China had been away for an hour and a half. Hannah and Harvey had gone out looking for her, and had walked the two hundred yards between home and the shop in the arcade, back and forward, four times. ‘I expect she’s gone to visit a friend of hers,’ Ruth said, irritated. Hannah had insisted. Harvey had wanted a PB and J, and had started bawling. China had gone to the shops—she knew he was sitting bawling, she’d have come straight back.

‘In any case,’ Heidi said to the police later, quite calmly, ‘I knew China hadn’t gone to visit her friends for one straight and simple reason. She doesn’t have any friends. She’s not been a popular girl, ever. They bully her, I expect, because they say she’s fat and she smells. I don’t think she smells, but at that age, it’s always some reason they’ve got to pick on her, isn’t it? I knew she hadn’t gone to visit a friend. To tell the truth, I thought at first, China, she’s playing some trick on her brother and sister. I’ll tan her hide, I thought at first.’

When Micky came back, it was seven thirty. After his appointment at the library, he’d arranged to meet an associate in a pub by the station, and they’d sunk a fair few before Micky had said it was time for him to be getting back. (A junior librarian, the associate and a bored barmaid had confirmed all of this. The barmaid said she’d never have served him the last few if she’d thought for one moment that he’d be getting in a car and driving anywhere.) By the time he got back home, a small crowd of neighbours had gathered at Heidi’s front gate. Micky got out of the car, his blue and yellow hooped T-shirt outlining ample belly and breasts. The neighbours let out a moan of satisfied excitement and interest.

‘What’s going on?’ said Micky. The door to Heidi’s house was hanging open. Ruth came out and looked at him with one of her grimmest faces. By eight, the police had arrived.

4. (#ulink_2a3f2e6c-de15-51a7-9357-b198f8f61113)

There is, of course, no need to worry. There is a process. It is a police process, evolved and tested by a thousand cases that never come to court. That never last more than five hours, most of them. The process searches for a child in a succession of ways, each larger, each more serviced, each more public than the one before. There might be a metaphor here: a series of sieves, each one finer than the previous one. At first the obvious, the nearby is tested, a very few people. But more and more people fall into the sieve, and after a while, everyone is being tested. It escalates, the process, and it escalates quickly. Another metaphor: an escalator, rising like a cliff, speeding—a better metaphor—like a glass lift, rocketing upwards. A case is either solved unobtrusively and swiftly, or it arrives on the front pages of the national newspapers. Almost always it is solved swiftly, and nothing more is heard of it; nobody not related by blood to the child ever hears of it. But there is a process, and it is followed.

The police arrived around eight o’clock. There were two of them at first. They took notes. A male policeman and a policewoman. They sat in Heidi’s apricot lounge, each at the edge of the sofa, smiling wanly. They balanced their notebooks on their knees. ‘Don’t worry,’ one said. ‘Children disappear, and most of them turn up quickly.’ And this was true. They asked about birthday parties China had gone to. They asked about her best friends, and where they lived; about everyone China had ever known on the estate. The children came in, and could add another ten names, tumbling over each other in their urge to be helpful.

‘She’s not with any of them,’ Heidi’s friend—sister-in-law, in fact—Ruth said, walking in and walking out again contemptuously. ‘You’re wasting time.’

The police explained to Heidi—because Ruth had not stayed for an answer—that this was always the first line of enquiry. And then, within half an hour, they left with the names of everyone China knew, as far as Heidi and the children were aware.

The police multiplied. They went to thirty addresses, most of them similar yellow-brick houses on the estate. It was quite late in the evening by now. They knocked on the doors, and a parent came, wondering who it was. A child was summoned from bed or television. But, no, China had not been seen by any of them, not since that afternoon. She’d gone, everyone knew that, she’d disappeared, some of them said; she was there in the street one moment and she was gone the next, the best-informed of them said. By midnight, the last of the names had been canvassed. By midnight in these cases, the process says, most children who have been reported missing in the day will have come home of their own accord. But China had not come home.

Kitty liked to get up early; make a brisk start to the day. When Dennis was still alive, after they had retired, he preferred to stay in bed if he could, sometimes until ten or ten thirty. Kitty’s hours between seven and Dennis’s rising were her own; she could read, or do a touch of quiet gardening in the tubs in the courtyard, or get on with any quiet little task. Or she could simply close the wicket gate behind her and go out for a walk through Hanmouth in the early-morning light, enjoying the wind, or the sun, and the weather, and the shifting moods of the estuary.

Now she was on her own, but she still liked to make a brisk start. Some people did; most people didn’t. There was a small conspiratorial club of early risers, out and about by seven. That was how she had met half the people she knew in Hanmouth, after greeting them as they sailed out in search of their morning paper. Now, turning the corner into the Fore street from the little snicket that led nowhere but to her own back gate, she found herself facing Harry, another of these early risers, with the Guardian in his hand.

‘Hell of a lot of police about this morning,’ Harry said, when they had exchanged the usual greetings. ‘You don’t know what it’s about?’

‘I hadn’t seen,’ Kitty said. ‘I’ve only just come out.’

‘A hell of a lot,’ Harry said. ‘Down the Wolf Walk, poking round the car park at the doctor’s surgery, and there’s even a chap putting on scuba gear with his legs dangling over the quay. Dozens of them.’

‘Gosh,’ Kitty said. ‘How exciting. The Queen’s not coming, is she?’

‘Not that I’ve heard,’ Harry said. ‘I can’t think what it could be.’ He waved briefly with his umbrella, and let Kitty go on her way.

The next stage of the police process had begun overnight. It had not been announced. At first light, mud-brown and frail, twenty police were scattered over the wild places of the parish; wherever was overgrown and abandoned, wherever was wild, the police were. At the edges of Hanmouth, the clouded dawn showed police eyeing empty lands: the bird sanctuaries, the abandoned huts and sheds and workshops, which can be found everywhere in England. In the warm night, the police had arrived in vans, and in the fields about the city, in the woodlands, in long waders in the muddy estuary, the police walked with a strange, crane-like gait, their faces downwards, no more than a body’s length between them. They went slowly and gracefully through the waste ground, the unfarmed lands, the woods and clearings, and even along the undredged river. As Harry had seen, there was a scuba diver sitting at the edge of the quay, and soon, when the shifts ordained by the police authority changed, there were four more, at the quay, at the jetty, along the Wolf Walk. They plunged into the high water, again and again, surfacing, plunging, surfacing in further and further places. On the quay, a senior policeman stood; he did not take his own notes, but had a subordinate to do that. From time to time, he was informed of progress. Last night he had not been told about the girl’s disappearance. This morning he had been told, and he was inspecting the wild places, the hiding places, the places where a child could disappear and find no way out. The mood was calm and systematic. They were working through their process. By eleven, the tide was low, and the wet, brackish mud hissed as the water drained from it, like geese or rain. The scuba divers stood in it, thigh-deep. There was nowhere to go but further towards the ocean, where the estuary still ran deep and secret.

‘Apparently,’ Doreen Harrington said in the coffee shop at eleven, ‘they’re looking for a small girl. Gone missing.’ She popped a gobbet of cheese scone into her mouth, swilled it with coffee, and went on talking, her manners not being all they should be.

‘I saw some police divers at work in the estuary as I was coming out,’ her friend Barbara said. ‘Has she fallen in, do they think?’

‘They don’t know,’ Doreen said. ‘I was speaking to a nice young constable—I saw him going into the old workshop at the back of me, the abandoned one, and I didn’t see his uniform at first. I thought it might be kiddies going in to make mischief, so I went over to chase him out, but he explained everything. It’s a little girl from the estate; she disappeared yesterday afternoon and hasn’t been seen since. They don’t know what’s happened to her. The divers, it’s just a precautionary measure.’

Mary and Kevin, who ran the coffee shop, had heard Doreen’s informed knowledge. They now came over, he from the kitchen in a striped and flour-dusted blue butcher’s apron, she in a waitress’s frilly one, a pencil in hand. ‘I do hope she hasn’t been—that there’s no talk of anyone taking her—that—’ Mary said.

‘Paedophiles, you mean?’ Doreen said, in a frank, open tone. ‘They simply don’t know.’

‘But they wouldn’t be fishing in the estuary, would they,’ Barbara said, ‘if they thought it was paedophiles?’

‘They have to exclude every possibility, systematically,’ Doreen said, whose nephew was a constable in the Hampshire constabulary. ‘They’re doing all the right things, I’m sure.’

In the possession of the police was another list of names. Unlike the list of China’s friends and acquaintances, gathered by talking to her mother, to Micky, to her aunt and her siblings and her other friends, this was kept securely on a computer, and not printed out lightly, not shown to anyone outside the police service. On it were the names of those in Devon and Cornwall who had been convicted or accused of some sexual crime against children. Some of them had fucked eight-year-old nieces thirty years ago, and had recently been released from decades of drinking prison tea, pissed in by generations of kitchen-serving muggers. Others had been found with images of carefree naked toddlers on their computers, each one fairly unobjectionable, but amounting to a collection of tens of thousands. One unfortunate had, in 1987, had sex with a bricklayer who turned out to be twenty years old and thus below the age of consent; he, too, found himself on the police’s list of slavering lunatics beside the others with horrible designs on toddlers. There seemed no means of removing him from the police list, and he, like all the others, received a visit from the police in the little pink-fronted terraced house in Drewsteignton with a rainbow sticker in the window where he lived with the same bricklayer, now in his forties.

‘Someone’s taken her, I know it,’ Heidi was saying. ‘They’ve taken her, they’ve definitely taken her.’

Her apricot sitting room was crowded now: five police officers, Micky, Ruth, and a man from the local press as well as Heidi. The police didn’t know how he had got there and who had asked him, but he was taking notes silently, as if in competition with the woman police officer on the arm of the sofa doing the same thing. And there was someone else no one knew what he had to do with anything; a man called Calvin, well-dressed and elegant. One of the officers knew him, apparently, and had said, ‘Hello, Mr Calvin,’ when he had come in, so nobody had challenged him. Heidi wanted him to be there, it seemed; she turned to him from time to time instead of answering a question. He was an improbable friend for Micky or Heidi, but he nodded and smiled, or shook his head and frowned when appealed to. He had some role, possibly self-assigned. Outside on the stairs, the children sat, Ruth’s mother guarding them in watchful silence.

‘She hasn’t fallen into the estuary,’ Ruth said. ‘I said she hasn’t. We knew she hadn’t gone playing hide and seek, or gone off to visit one of her friends without telling anyone. We told you that yesterday. I told you she’d been taken by someone.’

‘We have to explore every possibility,’ one of the police officers said. ‘We’re dedicating a very large number of officers to this case. This morning, they have started paying home visits to every individual in the area known to us with some sort of record. You needn’t have any concerns about that.’

‘Oh, my God,’ Ruth’s mother said, coming into the room. ‘You’re telling us that there are people who have done this, living here, living round here sort of thing?’

‘Those are our first port of call,’ the police officer said.

‘Living here, on the estate?’ Micky said. ‘Who are they?’

‘Not necessarily here on the estate.’

‘Are they supposed to be living in Hanmouth?’ Ruth said. ‘Or Old Hanmouth?’

‘I’m very sorry,’ the police officer said, ‘but I can’t give you that information.’

‘I heard,’ Billa said to Sam over the telephone—he was only in his shop, not thirty yards away across the street, but it seemed altogether best to telephone, or Tom would be asking where she was going, ‘that there’s a little girl gone missing… Yes, I know. Just yesterday. A policeman came round to ask if we had a shed, or something. As if she were a lost cat… No, not at all. I don’t think she’s from Hanmouth properly speaking—I think Kitty said she went missing from up the road, on that post-war estate you drive past… That’s right. But Tom was speaking to another police officer, I think a more senior one, and he was saying that they now think the girl’s actually been taken by someone. Isn’t that frightful?… No, nobody saw anything. Apparently she was there one moment and gone the next. No car or anything. That’s why they thought at first she had run away, I suppose, but now they do think that she must have been abducted. You simply don’t think of that sort of thing happening in Hanmouth. How are you getting on with that Japanese novel? I can’t think why we agreed to it, I can’t get on with it, not one bit… Yes, do drop in, six-ish or whenever you close up—bang on Kitty’s door on your way over, we’ll make a little party of it.’

‘Have you just invited some ghastly reprobates to drink us out of house and home?’ the Brigadier called from his study, just next door.

‘Yes, I rather think I have,’ Billa said. ‘Don’t be such an old curmudgeon. You really are a wretch. It’s only Sam, in any case.’

‘Well, I warn you,’ the Brigadier said. ‘There’s not a drop of Campari in the house. He finished it the last time he was here.’

Billa had a couple of small purchases to make as well as the Campari, so she went out to the Co-op on the Fore street. Outside her door, there were clusters of people, twos and threes, outside the bookshop, the travel agent, the jeweller’s, all talking in urgent, restrained style. She might have thought they were talking about her, from the way they hushed and broke off as she approached. And there, as advertised, were two police officers, making their way from door to door. She wondered that they hadn’t made it to their house yet.

In the Co-op, she picked up what she needed—a pack of Lurpak, some emergency washing powder, some savoury biscuits and some loo roll as well as the Campari. It was extraordinary how these things ran out between trips to the supermarket. When she got to the till, on the counter there was the local newspaper. It came out in the evening, and on the cover was a photograph of a fat-faced child, grinning and gummy, evidently an unflattering school photograph. Next to her was a photograph of rather an attractive, though staring, blonde, holding that same photograph on a yellowish leather sofa; around her a thick-looking youth had his arm draped. The headline read, ‘WHERE IS CHINA?’

The girl on the till could have been quite pretty, with her straight red hair and her lucid freckled skin, Billa believed, if she had only had her gravestone teeth fixed. ‘Terrible, this,’ the girl said, gesturing at the newspaper. ‘Terrible.’

‘You never think it will happen in the place you live,’ Billa said. ‘The poor mother,’ and then, hardly meaning to, she picked up a copy of the deliriously untalented local newspaper, something she never bought or read. So when Sam came through the door an hour later, saying, ‘Isn’t it appalling?’ Billa and, more surprisingly, Tom, who joined them for once, had found out a good deal about the case and the poor family. Tom thought he recognized the mother. Nobody recognized the little girl. It was shocking that such things could happen, virtually on their doorstep. In the end, Kitty and Sam stayed for dinner, and Billa insisted that Sam phone up Harry and ask him over, as well.

China was officially missing. Two police officers were assigned to sit with Heidi. Ruth was sitting in the kitchen, incessantly smoking Marlboro Lights, waiting to be called in by her friend. Karen was despatched to a hotel and told that she would be needed in the morning. The children, wide-eyed, excited and frightened, were put to bed while the adults were interviewed. Out in the streets, search parties were setting off, door-to-door, like weary electioneers. On the third day, long before nine, the house towered over a makeshift refugee camp of silver reflective canopies, car batteries, tents, aluminium stools and ladders, men and women all facing in the same direction away from the house and talking, all of them ignoring each other in their steady monologues. Behind them, a curtain moved, a small face could be seen. By the afternoon, the crowds had doubled, and the first strangers arrived on the main street of Hanmouth.

5. (#ulink_c996569a-005c-5f53-a74a-2de766535a20)

At some point in the next few days, somebody in Hanmouth, behind closed doors—some cynical millionaire on the Strand, talking to some other cynical millionaire—after an hour or two of pious public conversation, paused, and judged their interlocutor, and let their interlocutor judge them. Who was it who said it first? It hardly matters, because soon everyone would be saying it. They said, ‘Do you think—I mean, do you think it’s remotely possible—I know it sounds simply extraordinary, but I can’t help wondering—’

And by the end of the week, that was what Hanmouth was saying, and, quietly, the press and, even more quietly, the police when they were alone with each other. ‘You don’t think, do you, that Heidi could possibly…’

But they both looked at each other, whoever they were, and clapped a hand to their mouths, their eyes wide, then lowered their hands and, rather quietly, began to talk.

6. (#ulink_c8368689-d95f-5a04-be01-f54a2ab87c59)

In an upper room in a house in the Strand, looking out onto the estuary through leaded windows, a girl sat with her twenty-nine companions. This morning there had been twenty-eight; as before, she had gone out, obeying her mother’s frequent instruction, ‘Why don’t you go out instead of staying in all day long? Go out and make some friends.’ She’d gone out, mooched around the post office, where she’d bought a biro. She’d stood outside the town hall and the Crapping Juvenile. One of the grockles might photograph her and ask her if she knew about that girl that got kidnapped. Or even better, the kidnapper might turn up and try and kidnap her, and she’d scream and get the hatpin out of her pocket and stab him in the back of the hand until he bled and he was screaming for mercy down Hettie’s white shirt. That would be good in front of all of the grockles. Hettie sat on the wall outside the community centre until one of her mother’s friends, passing with a stupid shopping trolley with big pink flowers on it had recognized her and said hello. It was that old woman Billa who lived in the flat sideways house that always gave you the creeps because it looked so witchy. ‘Tell your mother I’m looking forward to tonight,’ the old woman said.

‘I will!’ Hettie said, smiling as stupidly as she could, and the old woman, Billa, she didn’t even realize Hettie was being sarcastic, so Hettie waved, though Billa was only two feet away, and even then she didn’t realize: she made a laughing noise and waved back, as though it was Hettie being stupid.

So then there was no point in sitting there because Hettie had been there for a million hours and no one had come to take her photograph and kidnap her. She might as well go. Hettie, like a prize-winning gymnast taking her bow in front of thousands as she came to the end of her routine, sprang off the wall and made a perfect finish with her feet together in the nine o’clock position. But no one saw, which was typical. On the way back home, she went first into the second-hand bookshop and said hello to Maggie who worked there. She didn’t buy any books. Maggie would tell her mother she had come in, which was the same thing. Then she had got to the place she’d been going to go to all the time. She’d been delaying it, looking forward to it. She had gone inside the antiques centre on the quay, ignoring the old man, in a brown cardigan the weather was too hot for, at the front desk where you paid. She had made a pretence of looking at the stalls downstairs, with mismatching teacups and the sets of glasses and cutlery no one would want because they’d come directly from dead people. (Glasses raised to mouths that were rotting, the skull beneath the face showing as the old flesh fell away; cutlery fixed in fists in rigor mortis—she’d died over her individual cottage pie on the Friday and nobody had found her until the Monday; she’d had to be buried with a fork and a knife in each hand, and the rest of the cutlery canteen sent to the Hanmouth antiques centre.) Then she had gone upstairs. She was too impatient by now, and went to the stall she had had in mind without any delay. It was the stall that had sold her the hatpin, last year; the one Hettie had in her pocket and took everywhere for good luck. They had what she was looking for.

‘Hello, there, young lady,’ the one who took the money had said. ‘Are you sure? Lots of other lovely dollies in the far corner.’

‘Yes, I’m sure,’ Hettie had said, holding out her two-pound coin.

‘It’s just that this one…’ the old one said. ‘It doesn’t have a right arm, you see. Don’t you want a dolly with all her parts?’

‘I didn’t know they made dollies,’ Hettie said, emphasizing the word sarcastically, ‘with all their parts. I don’t know that I’d want one. That sounds awful.’

The old one had taken the money; she hadn’t missed Hettie being sarcastic; and Hettie had taken the one-armed doll-child home to meet its fate.

There were twenty-eight participants in the upper room, and Hettie to arrange everything. Twenty-seven of them had been there for ever, and had their names in everyday life: there was Sad Child, Harriet, Lucinda, Weeping Real Tears, My Little Pony One and Two, Wedding Dress My Little Pony, Kafka, Horseradish, Little Hattie, the Lady Mayoress of Reckham, Cappuccino, Bloodstained Victim, Dead In Childbirth, Mother, Big Hattie, Death, Widow, Child Pornography, Slightly Jewish, Shitface, Pretty Girl, One Eye Doesn’t Work, Dressed As A Man, Rebecca Holden, Lipstick and Hole. Rebecca Holden in real life was a girl in her class with lovely hair, straight down, and thin, who had never spoken to Hettie, though Hettie always got better marks than her. Today they were lined up, twelve of them, including the ponies, in two rows; they were the jury. Two barristers and two juniors and a Clerk of the Court. Then there were members of the public and the victim’s family and the press, and Child Pornography was the judge because of her white curly hair a bit like a wig. The new doll with only one arm didn’t have a name. Hettie wasn’t going to waste one on her. She was just The Accused.

‘Do you have anything further to say,’ Child Pornography said, in a gruff, legal voice, ‘before sentence is passed upon you?’

‘I have something to say,’ called Slightly Jewish from the relatives’ box. She lisped for some reason. ‘She was my little girl and you took her away from me.’

‘Murderer! Beast! Paedophile!’ Two members of the public had called out, Little Hattie and the Lady Mayoress of Reckham, jumping up and down excitedly in either hand. Then one of the ponies, the one with the wedding dress, forgot that she was in the jury and started shouting, ‘You fucking bastard.’

‘Silence in court,’ Child Pornography said, in the special low voice she had when she was the judge. ‘I have heard the jury’s verdict and all the evidence and it is clear that you are guilty of all the charges and that you kidnapped and paedophiled this innocent victim, who was as beautiful as the day is long. I sentence you to twenty years of being done with the hatpin.’

The Accused hadn’t spoken so far, but now he leapt into Hettie’s left hand and started pleading for anything at all but the hatpin, waving his one arm about. Too late! The hatpin and Hole the executioner were already in Hettie’s left hand, and now began to stab the Accused, once, twice, three times. There were little screams and grunts as the punishment proceeded. In a moment or two it got too hard to hold Hole and the hatpin in one hand and to stab the new doll at the same time. Hettie dropped Hole, and went on stabbing with the hatpin into the doll’s head, body, legs, now silently. In fifteen minutes, the doll was torn, small scraps of rubber bearing the imprint of half a mouth on the carpet; the pathetic little eye, scraps of hair torn from the fascinatingly meshed scalp; and all around, the twenty-eight dolls lined up and looked with satisfaction on what happened to people who did bad things, and on the hatpin. ‘There,’ Child Pornography said, but it was in Hettie’s voice now, and she only moved her up and down for the sake of it. ‘Let that be a lesson to you not to kidnap and torture in future.’

‘You know it’s my book group this evening,’ her mother called from downstairs.

‘Yes, I know,’ Hettie said. She could hear how her voice sounded excited and stifled.

‘What are you doing up there?’ the voice called, with a definite inquisitorial edge.

‘Nothing. Just mucking about.’

‘Well, you know you’re welcome to come and sit in on the book group,’ the voice said.

‘I’ll sit up here and watch telly,’ Hettie said. There was a sigh, meant to be heard up a staircase and through a solid bedroom door.

‘Really,’ Kafka said, in an unusually sophisticated and mature voice, ‘Miranda should, to be perfectly honest, have overcome her disappointments by now. It’s not as if she doesn’t know perfectly well that—’

‘That’s right,’ Hettie said, cutting Kafka off. You never knew what Kafka might or might not say when she was in a certain mood.

7. (#ulink_f896409f-7d48-5cc0-b7f2-09b3fdc3b077)

Kenyon was running for his train across the broad and half-aimless crowd at Paddington station. The gormless, slow and humourless west began with the prevailing manners of Paddington station, and across it, Kenyon ran like a Londoner with somewhere to go. Knees up, his jacket and briefcase-cum-weekend-bag in the other, he had only two minutes, perhaps not that, to catch his train. (The ticket, bought parsimoniously six weeks before, had cost thirty pounds, but was for this exact train. If he missed this one, and caught the next, his ticket would be invalid and he would have to pay sixty-three pounds for a new one; so he ran.) Kenyon led an orderly life, organized weeks in advance, planned in accordance with the convenience of the First Great Western train company. But there had been a last-minute query from the Department about the reported Ugandan infection rates in a paper he’d written for them; the Underground had groaned inexplicably to a halt shortly after Euston Square; pushing aside massively laden Spaniards who did not know which side to stand on, he had run up the black and greasy steps and iron escalators of the Underground, diagonal, hung and groaningly floating over great unspecified voids, like public transport envisaged in a nightmare by Piranesi. Now he ran across the ‘piazza’, as it was now festively renamed. The holidaymakers heading for the west, with their surfboards, rucksacks the size of a sheep, square brown suitcases dug out of wardrobes, sat in his path like deliberate obstacles, like a miniature village. He jinked and swerved among the slow-witted and the heavy-laden like a man divided between his consciousness of an almost certainly lost something, and his fierce intention towards that train, there, that particular one, behind the barrier.

He had read somewhere that the identity of the 16.05 train to Anytown resided in its distinction, its differences, and that presumably a train that ran only the once could have no identity at all. It remained the same from day to day, still the same 16.05, despite being constituted out of different engines, different carriages, staffed by different individuals and carrying entirely different complements of passengers. Philosophically true that might be, but the identity of this one, beyond the barrier, did not seem remotely mutable, at all capable of replacement with different units as he fumbled with his ticket and limbs and thrust-out bags in the general direction of the ticket-checking machine at the barrier and ran towards the first carriage. A guard already stood by the door of the first-class carriage, arm raised. This train, he felt, was unique, and he hardly noticed the youth on this side of the ticket barrier who seemed in no hurry to get on the train, kneeling by an open black case on the platform between waiting trains. It was as if he had nowhere very much to go. But at the time Kenyon barely gave him a thought.

‘Only just made it,’ said the guard, in tones of quite pointless admonition. Kenyon clambered on, and into the first-class carriage, where the other passengers gave him half a glance before raising their newspapers against him, lowered their faces to their books, or just turned their heads away. Kenyon, dripping, purple-faced, crumpled, stumbled up the aisle panting with his detritus-like luggage. He fell into his reserved seat. It faced the wrong way, with, as a man of Kenyon’s age and class still put it, its back to the engine. This was either due to Kenyon’s vagueness when booking or the railway company’s incompetence. Around him, everyone was tactfully engaged in things that meant they didn’t have to look at Kenyon just for the moment.

Out of the window, the guard blew a whistle and raised an arm. Some sort of electronic signal within signified the locking of the doors. Almost at the same moment on the platform, the young man in the nondescript camel-coloured duffel coat, completely wrong for the temperature and the time of year, raised himself in a leisurely way from his crouching position over the black case. Somewhere further away there was a cry, then a number of shouts. The noise was muffled in the compartment. The train began to move away. The man raised his right arm, his left hand gripping his right wrist. There was a popping sound, as if of a balloon, then another. The train continued to move. Kenyon’s last impression was of a vague and retreating mass of people, running and throwing themselves to the marble floor, or perhaps being shot and falling to the floor. The small resolute figure stayed where it was, its arms outstretched with a firing weapon at the end of them. The train slid out from the station canopy around the concealing curve, into the sunlit railway path, lined with sunlit towers, of west London.

‘Did you see that?’ Kenyon said. He asked nobody in particular, and nobody answered. Perhaps nobody had seen it. The pages of the newspapers between his fellow passengers and Kenyon stayed where they were. Something in the angle of the sheets made it clear that they were not being read. They were thinking of Kenyon’s sweating dishevelment, and would lower them when he might have cooled down and stopped panting like a dog. So it was left to Kenyon to read the story on the front page of all of them. It was concerned with the small town he lived in and where he was travelling to. Tomorrow, those same front pages would be filled with what he had just half seen, a teenager shooting at random at strangers at Paddington station on a sunny afternoon. None of them would mention what seemed most noteworthy to Kenyon, that a train had managed its departure at the exact same moment, as if the shooting were no more than a trivial and irrelevant part of the station’s normal work. He concluded, as the train went on with a smooth lack of feeling or shocked response, that he was being swept away from one catastrophe towards another. The world was experiencing an ugly abundance of news, and its experience in the face of that abundance was neglected and unshared. Nobody knew what it was like to travel from the site of a mass shooting towards the site of a child’s kidnapping, and sit in a first-class compartment, the only announcements to listen to those coming from the buffet, about hot and cold drinks, snacks and light refreshments.

It could have been a delirious dream. But at the first stop, Reading, the platforms were milling with disgorged passengers beyond the extinguished trains. They had the patient and forest-like appearance of English people asked to stand and await news about an inconvenient but remote crisis. The crisis, remote as it was, had not been enough to erase the difference between travelling strangers, and for the moment they stood separately without coming together to share observations. ‘Due to an incident,’ an announcement from the platform began. The doors shut, the train moved on. Like a forlorn responding bird call, the Tannoy said, ‘For the benefit of customers joining us at Reading, the buffet is now open for the sale of light refreshments, snacks, tea and coffee, soft drinks and alcoholic drinks. Please have the correct change if at all possible.’ There was nothing in the westward direction to detain them, after all.

8. (#ulink_af828f18-716a-5873-be48-fa3ea24afc67)

On an early summer evening in a medium-sized city in the west of England, a more than customary crowd stood on a railway platform and noisily waited. Between the tracks, someone had once placed heavy concrete troughs and had planted them. Nobody, however, had tended them for years. A tattered linear meadow had spread. Scraggy meadowsweet and Michaelmas daisies had seeded themselves in the gravel between the lines and even along the tracks. They grew leggily, their flowers patchy and periodic as a disease of the skin.

The holiday atmosphere had spread up the line from Hanmouth. Caroline inspected the other passengers coldly, fingering the Moroccan beads at her neck. On this line, you got the squaddies from the camp at Reckham. They were bony, pimpled youths with identically applied and variously successful haircuts. With them was the miscellaneous and motley humanity, and its sourly unpromising children, that had washed up finally at the grim and dole-funded settlements where the train ground to a halt. They all came into Barnstaple to shop, to have an afternoon’s spree, to be subjected to a modicum of education. Today, too, there were others: prim middle-aged couples in neat gear, as if for Sunday-morning drinks, and professionals, too, with a notebook or a complex camera about their necks. One such professional had insinuated himself into a seaside group of teenagers: a fat, womanly Goth in an unseasonable floor-length black leather coat and purple eyeshadow, his dead-black hair plastered to his scalp with sweat, and with him, three blonde girls, non-matching and clean, in floral sprigs or mini-skirts, pastel in overall effect. The professional—the journalist—was polo-shirted and knowledgeable rather than knowing in appearance. He was committing their comments to a list-sized notebook, flicking the short pages over as he scribbled. The children talked one over the other, craning over his shoulder to wonder at his shorthand.