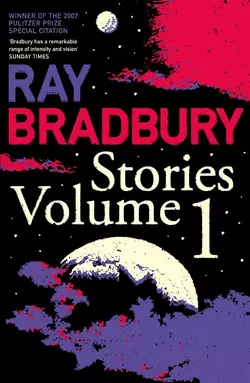

Ray Bradbury Stories Volume 1

Рэй Дуглас Брэдбери

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1396.59 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: One hundred classic stories from the celebrated author of Fahrenheit 451.In this, the first volume of Ray Bradbury′s short stories, some of the author′s finest works are published together, among them ‘Homecoming’, ‘Veldt’, ‘A Sound of Thunder’ and ‘The Long Rain’.Join an ill-fated crew of astronauts pushed to the brink of insanity by the incessant and highly corrosive rain on Venus, a high-tech virtual reality playroom that comes to life with terrible consequences, and a safari company offering tours for the wealthy back in time to the prehistoric era to stalk and kill dinosaurs, resulting in the present they return to being irrevocably altered.This collection is a rare treasure trove of wonder; as apprehensive about technology and the fate of humanity as it is elegiaic of its irrepressible progress. Each story presents an enlightening and poetic facet of Bradbury’s writing, every one as relevant now as when it was first written.