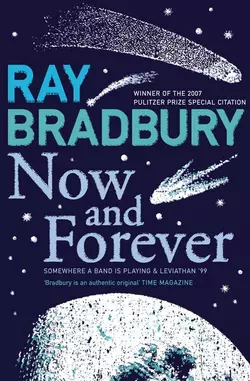

Now and Forever

Ray Douglas Bradbury

Two dazzling novellas from the celebrated author of Fahrenheit 451.Two previously unpublished novellas comprise this astonishing new volume from one of science fiction's greatest living writers. In the first, 'Somewhere a Band is Playing', newsman James Cardiff is lured through poetry and his fascination with a beautiful and enigmatic young woman to Summerton, Arizona. The small town's childless population hold an extraordinary secret which has been passed on for thousands of years unbeknownst to the rest of human civilization.In the second novella, 'Leviathan '99', the classic tale of Herman Melville's ‘Moby Dick’ is reborn as an interstellar adventure. It recounts the exploits of the mad Captain Ahab, who, blinded by his first encounter with a gigantic comet called 'Leviathan', pursues his lunatic vendetta across the universe. Born in space and seeking adventure in the skies, astronaut Ishmael Jones joins the crew aboard the Cetus 7 and quickly finds his fate in the hands of an indefatigable captain.Published together for the first time in one volume, these two stories twinkle with Bradbury's characteristically intricate metaphors and lyrical phrases. Both are a lasting testament to an older generation of writers that, much like the Leviathan itself, are on the threshold of passing on into the realm of legend.

Ray Bradbury

Now and ForeverSomewhere a Band is Playing&Leviathan ’99

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#ud3b694b6-dc36-5d98-b959-e41affb5e7c6)

Title Page (#u39cb151d-2fc1-5f9c-a5d1-2f8003a8bfef)

Somewhere a Band Is Playing (#u1367fab8-c757-5158-b447-f9dea14404ec)

Dedication (#u90b79dd4-83ee-5731-964a-8ca795f6dfd1)

‘Somewhere’: Introduction to Somewhere a Band is Playing (#uc37c263e-c7b9-52b5-93cf-a9c0c702540d)

Chapter One (#u60714c94-a3f4-5d96-8918-0bd15ed911e7)

Chapter Two (#udbe12ebb-e819-5bda-a2fe-b236a38ac3e9)

Chapter Three (#u5acf6727-a3e2-55ea-aa71-b267d13a3009)

Chapter Four (#ufd50e801-1eaf-56c8-9f83-f5ccc477eabc)

Chapter Five (#u65df56f3-71c0-54ba-a584-d7d062dfb2ae)

Chapter Six (#uca728830-236e-5002-b14a-0745a6c82686)

Chapter Seven (#u56eafd54-86cc-5452-85b4-16bd2717bfa6)

Chapter Eight (#u754d1e13-f172-596a-b0c2-184e77681424)

Chapter Nine (#u961620eb-7da9-5fe3-803f-f17e96c9c4a0)

Chapter Ten (#u830cc70f-8f5a-52fd-bfb8-17e66e2e6753)

Chapter Eleven (#uf5b1a046-244c-5a63-ab99-c958ea370efe)

Chapter Twelve (#ufe9ea65c-a69c-5d69-ad84-6d54f5a7e328)

Chapter Thirteen (#u21011aae-dea9-5955-8bdd-5ce4ab610a3f)

Chapter Fourteen (#uad150933-4ed3-5cae-b907-bb1343878f8c)

Chapter Fifteen (#udc5eafc4-f7a1-5644-822c-9e3b6c585f48)

Chapter Sixteen (#u2336a975-1cd6-5c68-9fee-88883c03396e)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Leviathan ’99 (#litres_trial_promo)

Dedication (#litres_trial_promo)

‘Radio Dream’: Introduction to Leviathan ’99 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

About The Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Other Books By (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Somewhere a Band Is Playing (#uf9970dbd-227a-5c42-a618-4422f5328221)

Somewhere a Band Is Playing …

for Anne Hardin and Katharine Hepburn, with love

‘Somewhere’ (#ulink_9c3c80a2-c951-5c41-9aed-7a28cc93d416)

Some stories – be they short stories, novellas, or novels – you may realize, are written as a result of a single, immediate, clear impulse. Others ricochet off various events over a lifetime and come together much later to make a whole.

When I was six years old my father, who had an urge to travel, took our family by train to Tucson, Arizona, for a year, where we lived in a burgeoning environment; for me, it was exhilarating. The town was very small and it was still growing. There’s nothing more exciting than to be part of the evolution of a place. I felt a sense of freedom there and I made many wonderful friends.

A year later, we moved back to Waukegan, Illinois, where I had been born and spent the first years of my life. But we returned to Tucson when I was twelve, and this time I experienced an even greater sense of exhilaration because we lived out on the edge of town and I walked to school every day, through the desert, past all the fantastic varieties of cacti, encountering lizards, spiders and, on occasion, snakes, on my way to seventh grade; that was the year I began to write.

Then, much later, when I lived in Ireland for almost a year, writing the screenplay of Moby Dick for John Huston, I encountered the works of Stephen Leacock, the Canadian humorist. Among them was a charming little book titled Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town.

I was so taken with the book that I tried to get MGM to make a motion picture of it. I typed up a few preliminary pages to show the studio how I envisioned the book as a film. When MGM’s interest failed, I was left with the beginning of a screenplay that had the feeling of a small town. But at the same time I couldn’t help but remember the Tucson I had known and loved when I was six and when I was twelve, and began to write my own screenplay and short story about a town somewhere in the desert.

During those same years I kept encountering Katharine Hepburn, either in person or on the screen, and I was terribly attracted by the fact that she remained so youthful in appearance through the years.

Sometime in 1956, when she was in her late forties, she made the film Summertime. This caused me somehow to put her at the center of a story for which I had no title yet, but Somewhere a Band Is Playing was obviously evolving.

Some thirty years ago I saw a film called The Wind and the Lion, starring Sean Connery and with a fabulous score by Jerry Goldsmith. I was so taken with the score that I sat down, played it, and wrote a long poem based on the enchanting music.

This became another element of Somewhere a Band Is Playing as I progressed through the beginnings of a story which I had not yet fully comprehended, but it seemed as if finally all the elements were coming together: the year I spent in Tucson, age six, the year I spent there when I was twelve, the various encounters with Katharine Hepburn, including her magical appearance in Summertime, and my long poem based on the score of The Wind and the Lion. All of these ran together and inspired me to begin a long prologue to the novella that ultimately followed.

Today, looking back, I realize how fortunate I am to have collected such elements, to have held them ready, and then put them together to make this final product, Somewhere a Band Is Playing. I have been fortunate to have many ‘helpers’ along the way. One of those, in the case of this story, is my dear friend Anne Hardin, who has offered me strong encouragement over the past few years to see this novella published. For that she shares in the dedication of this work.

Of course, I had hoped to finish the novella, over the years, in order to have it ready in time for Katharine Hepburn, no matter how old she got, to play the lead in a theater or film adaptation. Katie waited patiently, but the years passed, she became tired, and finally left this world. I cannot help but feel she deserves the dedication I have placed on this story.

ONE (#ulink_f8667a4c-9087-5e33-bf25-d28d3519851b)

There was a desert prairie filled with wind and sun and sagebrush and a silence that grew sweetly up in wildflowers. There was a rail track laid across this silence and now the rail track shuddered.

Soon a dark train charged out of the east with fire and steam and thundered through the station. On its way it slowed at a platform littered with confetti, the tatters of ancient tickets punched by transient conductors.

The locomotive slowed just enough for one piece of luggage to catapult out, and a young man in a summer dishrag suit to leap after and land running as the train, with a roar, charged on as if the station did not exist, nor the luggage, nor its owner who now stopped his jolting run to stare around as the dust settled around him and, in the distance, the dim outlines of small houses were revealed.

‘Damn,’ he whispered. ‘There is something here, after all.’

More dust blew away, revealing more roofs, spires, and trees.

‘Why?’ he whispered. ‘Why did I come here?’

He answered himself even more quietly, ‘Because.’

TWO (#ulink_963e75d6-4901-5c43-85d2-44b942281437)

Because.

In his half-sleep last night he had felt something writing on the insides of his eyelids.

Without opening his eyes he read the words as they scrolled:

Somewhere a band is playing,

Playing the strangest tunes,

Of sunflower seeds and sailors

Who tide with the strangest moons.

Somewhere a drummer simmers

And trembles with times forlorn,

Remembering days of summer

In futures yet unborn.

‘Hold on,’ he heard himself say.

He opened his eyes and the writing stopped.

He half-raised his head from the pillow and then, thinking better of it, lay back down.

With his eyes closed the writing began again on the inside of his lids.

Futures so far they are ancient

And filled with Egyptian dust,

That smell of the tomb and the lilac,

And seed that is spent from lust,

And peach that is hung on a tree branch

Far out in the sky from one’s reach,

There mummies as lovely as lobsters

Remember old futures and teach.

For a moment he felt his eyes tremble and shut tight, as if to change the lines or make them fade.

Then, as he watched in the darkness, they formed again in the inner twilight of his head, and the words were these:

And children sit by on the stone floor

And draw out their lives in the sands,

Remembering deaths that won’t happen

In futures unseen in far lands.

Somewhere a band is playing

Where the moon never sets in the sky

And nobody sleeps in the summer

And nobody puts down to die;

And Time then just goes on forever

And hearts then continue to beat

To the sound of the old moon-drum drumming

And the glide of Eternity’s feet;

‘Too much,’ he heard himself whisper. ‘Too much. I can’t. Is this the way poems happen? And where does it come from? Is it done?’ he wondered.

And not sure, he put his head back down and closed his eyes and there were these words:

Somewhere the old people wander

And linger themselves into noon

And sleep in the wheat fields yonder

To rise as fresh children with moon.

Somewhere the children, old, maunder

And know what it is to be dead

And turn in their weeping to ponder

Oblivious filed ’neath their bed.

And sit at the long dining table

Where Life makes a banquet of flesh,

Where dis-able makes itself able

And spoiled puts on new masks of fresh.

Somewhere a band is playing

Oh listen, oh listen, that tune!

If you learn it you’ll dance on forever

In June …

And yet June …

And more … June …

And Death will be dumb and not clever

And Death will lie silent forever

In June and June and more June.

The darkness now was complete. The twilight was quiet.

He opened his eyes fully and lay staring at the ceiling in disbelief. He turned in the bed and picked up a picture postcard lying on the nightstand, and stared at the image.

At last he said, half aloud, ‘Am I happy?’

And responded to himself, ‘I am not happy.’

Very slowly he got out of bed, dressed, went downstairs, walked to the train station, bought a ticket and took the first train heading west.

THREE (#ulink_4d73e0c1-0c69-5b19-89d5-05e5fbc9c465)

Because.

Well, now, he thought, as he peered down the tracks. This place isn’t on the map. But when the train slowed, I jumped, because …

He turned and saw a wind-battered sign over the flimsy station that seemed about to sink under tides of sand: SUMMERTON, ARIZONA.

‘Yes, sir,’ said a voice.

The traveler dropped his gaze to find a man of some middle years with fair hair and clear eyes seated on the porch of the ramshackle station, leaning back in shadow. An assortment of hats hung above him, which read: TICKET SELLER, BAGGAGE MASTER, SWITCHMAN, NIGHT WATCHMAN, TAXI. Upon his head was a cap with the word STATIONMASTER stitched on its bill in bright red thread.

‘What’ll it be,’ the middle-aged man said, looking at the stranger steadily. ‘A ticket on the next train? Or a taxi two blocks over to the Egyptian View Arms?’

‘God, I don’t know.’ The younger man wiped his brow and blinked in all directions. ‘I just got here. Jumped off. Don’t know why.’

‘Don’t argue with impulse,’ said the stationmaster. ‘With luck you miss the frying pan and hit a nice cool lake on a hot day. So, what’ll it be?’

The older man waited.

‘Taxi, two blocks, to the Egyptian View Arms,’ said the young man, quickly. ‘Yes!’

‘Fine, given the fact that there are no Egyptians to view, nor a Nile Delta. And Cairo, Illinois, is a thousand miles east. But I suppose we’ve got plenty of arms.’

The old man rose, pulled the STATIONMASTER cap from his head, and replaced it with the TAXI cap. He bent to take the small suitcase when the young man said, ‘You’re not just going to leave—?’

‘The station? It’ll mind itself. The tracks aren’t going nowhere, there’s nothing to be purloined within, and it’ll be some few days before another train takes us by surprise. Come on.’ He hoisted the bag and shuffled out of the gloom and around the corner.

Behind the station was no taxi. Instead, a rather handsome large white horse stood, patiently waiting. And behind the horse was a small upright wagon with the words KELLY’S BAKERY, FRESH BREAD, painted on its side.

The taxi driver beckoned and the young man climbed into the wagon and settled himself in the warm shadow. The stranger inhaled.

‘Ain’t that a rare fine smell?’ said the taxi driver. ‘Just delivered five dozen loaves!’

‘That,’ said the young man, ‘is the perfume of Eden on the first morn.’

The older man raised his eyebrows. ‘Well, now,’ he wondered, ‘what’s a newspaper writer with aspirations to be a novelist doing in Summerton, Arizona?’

‘Because,’ said the young man.

‘Because?’ said the older man. ‘That’s one of the finest reasons in the world. Leaves lots of room for decisions.’ He climbed up onto the driver’s seat, looked with gentle eyes at the waiting horse and made a soft clicking noise with his tongue and said, ‘Claude.’

And the horse, hearing his name, carried them away into Summerton, Arizona.

FOUR (#ulink_df952bae-c88b-5b5c-ac89-cf98d76c6be2)

The air was hot as the bakery wagon moved and then, as they reached the shadows of trees, the air began to cool.

The young man leaned forward.

‘How did you guess?’

‘What?’ said the driver.

‘That I’m a writer,’ said the young man.

The taxi driver glanced at the passing trees and nodded.

‘Your tongue improves your words on their way out. Keep talking.’

‘I’ve heard rumors about Summerton.’

‘Lots of folks hear, few arrive.’

‘I heard your town’s another time and place, vanishing maybe. Surviving, I hope.’

‘Let me see your good eye,’ said the driver.

The reporter turned and looked straight on at him.

The driver nodded again.

‘Nope, not yet jaundiced. I think you see what you look at, tell what you feel. Welcome. Name’s Culpepper. Elias.’

‘Mr Culpepper.’ The young man touched the older man’s shoulder. ‘James Cardiff.’

‘Lord,’ said Culpepper. ‘Aren’t we a pair? Culpepper and Cardiff. Could be genteel lawyers, architects, printers. Names like that don’t come in tandems. Culpepper and, now, Cardiff.’

And Claude the horse trotted a little more quickly through the shadows of trees.

The horse rambled through town, Elias Culpepper pointing right and left, chatting up a storm.

‘There’s the envelope factory. All our mail starts there. There’s the steam works, once made steam, I forget what for. And right now, passing Culpepper Summerton News. If there’s news once a month, we print it! Four pages in large, easy-to-read type. So you see, you and I are, in a way, in the same business. You don’t, of course, also rein horses and punch rail tickets.’

‘I most certainly don’t,’ said James Cardiff, and they both laughed quietly.

‘And,’ said Elias Culpepper, as Claude rounded a curve into a lane where elms and oaks and maples fused the center and wove the sky in green and blue colors, a fine thatchwork above and below, ‘this is New Sunrise Way. Best families live here. That’s the Ribtrees’, there’s the Townways’. And—’

‘My God,’ said James Cardiff. ‘Those front lawns. Look, Mr Culpepper!’

And they drove by fence after fence, where crowds of sunflowers lifted huge round clock faces to time the sun, to open with the dawn and close with the dusk, a hundred in this patch under an elm, two hundred in the next yard, and five hundred beyond.

Every curb was lined with the tall green stalks ending in vast dark faces and yellow fringes.

‘It’s like a crowd watching a parade,’ said James Cardiff.

‘Come to think,’ said Elias Culpepper.

He gave a genteel wave of his hand.

‘Now, Mr Cardiff. You’re the first reporter’s visited in years. Nothing’s happened here since 1903, the year of the Small Flood. Or 1902, if you want the Big One. Mr Cardiff, what would a reporter be wanting with a town like this where nothing happens by the hour?’

‘Something might,’ said Cardiff, uneasily.

He raised his gaze and looked at the town all around. You’re here, he thought, but maybe you won’t be. I know, but won’t tell. It’s a terrible truth that may wipe you away. My mind is open, but my mouth is shut. The future is uncertain and unsure.

Mr Culpepper pulled a stick of spearmint gum from his shirt pocket, peeled its wrapper, popped it in his mouth, and chewed.

‘You know something I don’t know, Mr Cardiff?’

‘Maybe,’ said Cardiff, ‘you know things about Summerton you haven’t told me.’

‘Then I hope we both fess up soon.’

And with that, Elias Culpepper reined Claude gently into the graveled driveway of the sunflower yard of a private home with a sign above the porch: EGYPTIAN VIEW ARMS. BOARDING.

And he had not lied.

No Nile River was in sight.

FIVE (#ulink_d58af8b4-0493-571a-abf6-ded976116ce4)

At which moment an old-fashioned ice wagon with a full dark cavern mouth of frost entered the yard, led by a horse in dire need of his Antarctic cargo. Cardiff could taste the ice, from thirty summers long gone.

‘Just in time,’ said the iceman. ‘Hot day. Go grab.’ He nodded toward the rear of his wagon.

Cardiff, on pure instinct, jumped down from the bread wagon and went straight to the back of the ice wagon, and felt his ten-year-old hand reach in and grab a sharp icicle. He stepped back and rubbed it on his brow. His other hand instinctively took a handkerchief from his pocket to wrap the ice. Sucking it, he moved away.

‘How’s it taste?’ he heard Culpepper say.

Cardiff gave the ice another lick.

‘Linen.’

Only then did he glance back at the street.

It was such a street as could not be believed. There was not a roof on any house that had not been freshly tarred and lathed or tiled. Not a porch swing that did not hang straight. Not a window that did not shine like a mirrored shield in Valhalla halls, all gold at sunrise and sunset, all clear running brookstream at noon. Not a bay window that did not display books leaning against others’ quiet wits on inner library shelves. Not a rain funnel spout without its rain barrel gathering the seasons. Not a backyard that was not, this day, filled with carpets being flailed so that time dusted on the wind and old patterns sprung forth to rococo new. Not a kitchen that did not send forth promises of hunger placated and easy evenings of contemplation on victuals contained just south-southwest of the soul.

All, all perfect, all painted, all fresh, all new, all beautiful, a perfect town in a perfect blend of silence and unseen hustle and flurry.

‘A penny for your thoughts,’ said Elias Culpepper.

Cardiff shook his head, his eyes shut, because he had seen nothing, but imagined much.

‘I can’t tell you,’ said Cardiff, in a whisper.

‘Try,’ said Elias Culpepper.

Cardiff shook his head again, nearly suffering with inexplicable happiness.

Peeling the handkerchief from around the ice, he put the last sliver in his mouth and gave it a crunch as he started up the porch steps with his back to the town, wondering what he would find next.

SIX (#ulink_1faf3c42-f841-567f-b527-3f2bf42d6f7d)

James Cardiff stood in quiet amazement.

The front porch of the Egyptian View Arms was the longest he had ever seen. It had so many white wicker rockers he stopped counting. Occupying some of the rockers was an assortment of youngish not quite middleaged gentlemen, nattily dressed, with slicked-back hair, fresh out of the shower. And interspersed among the men were late thirties-not-yet-forty women in summer dresses looking as if they had all been cut from the same rose or orchid or gardenia wallpaper. The men had haircuts each sheared by the same barber. The women wore their tresses like bright helmets designed by some Parisian, ironed and curlicued long before Cardiff had been born. And the assembly of rockers all tilted forward and then back, in unison, in a quiet surf, as if the same ocean breeze moved them all, soundless and serene.

As Cardiff put his foot on the porch landing, all the rocking stopped, all the faces lifted, and there was a blaze of smiles and every hand rose in a quiet wave of welcome. He nodded and the white summer wickers refloated themselves, and a murmur of conversation began.

Looking at the long line of handsome people, he thought: Strange, so many men home at this hour of the day. Most peculiar.

A tiny crystal bell tinkled in the dim screen doorway.

‘Soup’s on,’ a woman’s voice called.

In a matter of seconds, the wicker chairs emptied, as all the summer people filed through the screen door with a hum.

He was about to follow when he stopped, turned his head and looked back.

‘What?’ he whispered.

Elias Culpepper was at his elbow, gently placing Cardiff’s suitcase beside him.

‘That sound,’ said Cardiff. ‘Somewhere …’

Elias Culpepper laughed quietly. ‘That’s the town band rehearsing Thursday night’s performance of the shortform Tosca. When she jumps it only takes two minutes for her to land.’

‘Tosca,’ said Cardiff, and listened to the far brass music. ‘Somewhere …’

‘Step in,’ said Culpepper, who held the screen door wide for James Cardiff.

SEVEN (#ulink_b4ea5ae2-7d44-52ce-8e56-c5fee5a6c8e4)

Inside the dim hall, Cardiff felt as if he had moved into a summer-cool milk shed that smelled of large canisters of cream hidden away from the sun, and iceboxes dripping their secret liquors, and bread laid out fresh on kitchen tables, and pies cooling on windowsills.

Cardiff took another step and knew he would sleep nine hours a night here and wake like a boy at dawn, excited that he was alive, and all the world beginning, morn after morn, glad for his heart in his body, and his pulse in his wrists.

He heard someone laughing. And it was himself, overwhelmed with a joy he could not explain.

There was the merest motion from somewhere high in the house. Cardiff looked up.

Descending the stairs, and pausing now at seeing him, was the most beautiful woman in the world.

Somewhere, sometime, he had heard someone say: Fix the image before it fades. So said the first cameras that trapped light and carried that illumination to obscuras where chemicals laid out in porcelain caused the trapped ghosts to rouse. Faces caught at noon were summoned up out of sour baths to reestablish their eyes, their mouths, and then the haunting flesh of beauty or arrogance, or the impatience of a child held still. In darkness the phantoms lurked in chemicals until some gestures surfaced them out of time into a forever that could be held in the hands long after the warm flesh had vanished.

It was thus and so with this woman, this bright noon wonder who descended the stairs into the cool shadow of the hall only to reemerge in a shaft of sunlight in the dining room door. Her hand drifted to take Cardiff’s hand, and then her wrist and arm and shoulder and at last, as from that chemistry in an obscura room, the ghost of a face so lovely it burst on him like a flower when the dawn causes it to widen its beauty. Her measuring bright and summer-electric eyes shone merrily, watching him, as if he, too, had just arisen from those miraculous tides in which memory swims, as if to say: Remember me?

I do! he thought.

Yes? he thought he heard her say.

Yes! he cried, not speaking. I always hoped I might remember you.

Well, then, her eyes said, we shall be friends. Perhaps in another time, we met.

‘They’re waiting for us,’ she said aloud.

Yes, he thought, for both of us!

And now he spoke. ‘Your name?’

But you already know it, her silence replied.

And it was the name of a woman dead these four thousand years and lost in Egyptian sands, and now refreshed at noon in another desert near an empty station and silent tracks.

‘Nefertiti,’ he said. ‘A fine name. It means the Beautiful One Is Here.’

‘Ah,’ she said, ‘you know.’

‘Tutankhamen came from the tomb when I was three,’ he said. ‘I saw his golden mask and wanted my face to be his.’

‘But it is,’ she said. ‘You just never noticed.’

‘Can I believe that?’

‘Believe it and it will happen in the midst of your belief. Are you hungry?’

Starved, he thought, staring at her.

‘Before you fall,’ she laughed, ‘come.’

And she led him in to a feasting of summer gods.

EIGHT (#ulink_14eef679-3c35-504e-9fdf-cb061b689a69)

The dining room, like the porch, was the longest one he’d ever seen.

All of the summer porch people were lined up on either side of an incredible table, staring at Cardiff and Nef as they came through the door.

At the far end were two chairs waiting for them and as soon as Cardiff and Nef sat, there was a flurry of activity as utensils were raised and platters passed.

There was an incredible salad, an amazing omelet, and a soup smooth as velvet. From the kitchen drifted a scent that promised a dessert sweet as ambrosia.

In the middle of his astonishment, Cardiff said, ‘Hold on, this is too much. I must see.’

He rose and walked to a door at the end of the dining room, which opened into the kitchen.

Entering the kitchen, he stared across the room at what seemed a familiar doorway.

He knew where it led.

The pantry.

And not just any pantry, but his grandmother’s pantry, or something just like it. How could that be?

He stepped forward and pushed the door, half-expecting that he would find his grandmother within, lost in that special jungle where hung leopard bananas, where doughnuts were buried in quicksands of powdered sugar. Where apples shone in bins and peaches displayed their warm summer cheeks. Where row on row, shelf on shelf, of condiments and spices rose to an always-twilight ceiling.

He heard himself intoning the names that he read off the jar labels, the monikers of Indian princes and Arabian wanderers.

Cardimon and anise and cinnamon were there, and cayenne and curry. Added to which there were ginger and paprika and thyme and celandrine.

He could almost have sung the syllables and awakened at night to hear himself humming the sounds all over again.

He scanned and re-scanned the shelves, took a deep breath, and turned, looking back into the kitchen, sure he would find a familiar shape bent over the table, preparing the last courses for the amazing lunch.

He saw a portly woman icing a buttery yellow cake with dark chocolate, and he thought if he cried her name, his grandmother might turn and rush to hold him.

But he said nothing and watched the woman finish the job with a flourish, and hand the cake to a maid who carried it out into the dining room.

He went back to join Nef, his appetite gone, having fed himself in the pantry wilderness, which was more than enough.

Nef, he thought, gazing at her, is a woman of all women, a beauty of all beauties. That wheat field painted again and again by Monet that became the wheat field. That church façade similarly painted, again and again, until it was the most perfect façade in the history of churches. That bright apple and fabled orange by Cézanne that never fades.

‘Mr Cardiff,’ he heard her say. ‘Sit, eat. You mustn’t keep me waiting. I’ve been waiting too many years.’

He drew close, not able to take his eyes away from her.

‘Great god,’ he said. ‘How old are you?’

‘You tell me,’ she said.

‘Oh, hell,’ he cried. ‘You were born maybe twenty years ago. Thirty. Or the day before yesterday.’

‘I am all of those.’

‘How?’

‘I am your sister, your daughter, and someone you knew years ago back in school, yes? I am the girl you asked to the Senior Prom but she had promised another.’

‘That’s my life. That happened. How did you guess?’

‘I never guess,’ she replied. ‘I know. The important thing is that you’re here at last.’

‘You sound as if you expected me.’

‘Forever,’ she said.

‘But I didn’t know I was coming here until last night, in the middle of a dream. I fixed my mind only at the last moment. I decided to write a story …’

She laughed quietly. ‘How can that be? It sounds so like those unhealthy romances written by healthy housewives. What made you choose Summerton? Was it our name?’

‘I saw a postcard someone must have picked up on their way through.’

‘Oh, that would have been years ago.’

‘It looked like a nice town – a friendly spot for tourists looking for a place to relax, enjoy the desert air. But then, I looked for it on the map. And you know what? It’s not on any map I could find.’

‘Well, the train doesn’t stop here.’

‘It didn’t stop today,’ he admitted. ‘Only two things got off: me and my suitcase.’

‘You travel lightly.’

‘I’m just here overnight. When the next train runs through, not stopping, I’ll grab on.’

‘No,’ she said softly. ‘That’s not how it’s supposed to be.’

‘I’ve got to go home and finish my story,’ he insisted.

‘Ah, yes,’ she said. ‘And what will you say about this town that no one can find?’

A cloud crossed the sky and the dining room windows darkened, and a shadow fell across his face. There were two truths to tell, but he could tell only one.

‘That it’s a lovely town,’ he said, lamely. ‘The kind that doesn’t exist anymore. That people should remember and celebrate. But how did you know I was coming?’

‘I woke at dawn,’ she said. ‘I heard your train from a long way off. By noon the train was just beyond the mountains, and I heard its whistle.’

‘And did you expect someone named Cardiff?’

‘Cardiff?’ she wondered. ‘There was a giant, once—’

‘In all the newspapers. A fraud.’

‘And,’ she said. ‘Are you a fraud?’

He could not meet her gaze.

NINE (#ulink_942ea527-2ad9-5ccf-8506-af48a738185f)

When he looked up, Nef’s chair was empty. The other diners, too, had all left the table, gone back to their rocking chairs or, perhaps, to summer afternoon naps.

‘Lord,’ he murmured. ‘That woman, young, but how young? Old, but how old?’

Suddenly Elias Culpepper touched his elbow.

‘You want a real tour of our town? Claude needs to deliver some more fresh-baked bread. On your feet!’

The wagon was loaded with a redolent harvest. The warm loaves had been neatly stacked row on row within the oven-smelling wagon, thirty or forty loaves in all, with names lettered on the wax-paper wrappings. Beside these were waxed boxes of muffins and cakes, carefully tied with string.

Cardiff took three immense inhalations and almost fell with the overconsumption.

Culpepper handed him a small packet and a knife.

‘What’s this?’ said Cardiff.

‘You won’t be a block away before the bread overcomes you. This is a butter knife. This here is a full loaf. Don’t bring it back.’

‘It’ll ruin my supper.’

‘No. Enhance. Summer outside. Summer inside.’

He handed over a pad with names and addresses.

‘Just in case,’ said Culpepper.

‘You’re sending me out on my own? How do I know where to go?’

‘Don’t you worry. Claude knows the way. Never got lost yet. Right, Claude?’

Claude looked back, neither amused nor serious, just ready.

‘Just go easy on the reins. Claude’s got his own system. You just tag along. It’s the only way to see the town without any jabber from me. Giddap.’

Cardiff jumped aboard. Claude tugged, the wagon lurched forward.

‘Hell.’ He fumbled with the notebook, scanning the names and addresses. ‘What’s the first stop?’

‘Git!’

The bread wagon drifted away, warming the air with the heady scents of yeast and grain.

Claude trotted as if he could hardly wait to be right.

TEN (#ulink_eb2d361f-7198-56d1-ae17-ee915057ae1f)

Claude jogged at a goodly pace for two blocks and turned sweetly to the right.

His eyes twitched toward a front yard mailbox: Abercrombie.

Cardiff checked his list.

Abercrombie!

‘Damn!’

He jumped from the wagon, loaf in hand, when a woman’s voice called, ‘Thank you, Claude.’

A woman of some forty years stood at the gate to take the bread. ‘You, too, of course,’ she said. ‘Mister …?’

‘Cardiff, ma’m.’

‘Claude,’ she called, ‘take good care of Mr Cardiff. And Mr Cardiff, you take good care of Claude. Morning!’

And the wagon jounced along the bricks under a congress of trees that laced themselves to lattice out the sun.

‘Fillmore’s next.’ Cardiff eyed the list, ready to pull on the reins when the horse stopped at a second gate.

Cardiff popped the bread in the Fillmore mailbox and raced to catch up with Claude, who had resumed his route without waiting for his driver.

So it went. Bramble. Jones. Williams. Isaacson. Meredith. Bread. Cake. Bread. Muffins. Bread. Cake. Bread.

Claude turned a final corner.

And there was a school.

‘Hold up, Claude!’

Cardiff alighted and walked into the schoolyard to find a teeter-totter, its old blue paint flaking, next to an old swingset, its splintery wooden seats suspended from rusted iron chains.

‘Well, now,’ whispered Cardiff.

The school was two stories high. Its double doors were shut, and all eight of its windows were crusted with dust.

Cardiff rattled the front doors. Locked tight.

‘It’s only May,’ Cardiff said to himself. ‘School’s not out yet.’

Claude whinnied irritably, and perhaps out of pique, began a slow glide away from the school.

‘Claude!’ Cardiff put iron in it. ‘Stay!’

Claude stayed, drumming the bricks with both forefeet.

Cardiff turned back to the building. Carved in the lintel, above the main door were the words: SUMMERTON GRAMMAR SCHOOL, DEDICATED JANUARY 1ST, 1888.

‘Eighteen eighty-eight,’ Cardiff muttered. ‘Well, now.’

He gave one last look at the dust-caked windows and the rusted swing chains and said, ‘One last go-round, Claude.’

Claude did not move.

‘We’re all out of bread and names, is that it? You only take bakery orders, nothing else?’

Even Claude’s shadow did not move.

‘Well, we’ll just stand here until you do me a favor. Your new star boarder wants to cross-section the whole blasted town. What’s it to be? No water, no oats, without a full trot.’

Water and oats did it.

Full trot.

They sailed down Clover Avenue and up Hibiscus Way and over on to Rosewood Place and right on Juneglade and left again on Sandalwood then Ravine, which ran off the edge of a shallow ravine cut by ancient rains. He stared at lawn after lawn after lawn, all of them lush, green, perfect. No baseball bats. No baseballs. No basketball hoops. No basketballs. No tennis rackets. No croquet mallets. No hopscotch chalk marks on sidewalks. No tire swings on trees.

Claude trotted him back to the Egyptian View Arms, where Elias Culpepper was waiting.

Cardiff climbed down from the bread wagon.

‘Well?’

Cardiff looked back at the summer drift of green lawns and green hedges and golden sunflowers and said, ‘Where are the children?’

ELEVEN (#ulink_ff4e2b41-9c87-5f4a-9d22-0f29eab70bbd)

Mr Culpepper did not immediately respond.

For dead ahead there was afternoon high tea, with apricot and peach tarts and strawberry delight and coffee instead of tea and then port instead of coffee and then there was dinner, a real humdinger, that lasted until well after nine and then the inhabitants of the Egyptian View Arms headed up, one by one, to their most welcome cool summer night beds, and Cardiff sat out on the croquetless and hoopless lawn, watching Mr Culpepper on the porch, smoking several small bonfire pipes, waiting.

At last Cardiff, in full brooding pace, arrived at the bottom of the porch rail and waited.

‘You were asking about no children?’ said Elias Culpepper.

Cardiff nodded.

‘A good reporter wouldn’t allow so much time to pass after asking such an important question.’

‘More time is passing right now,’ said Cardiff, gently, climbing the porch steps.

‘So it is. Here.’

A bottle of wine and two small snifters sat on the railing.

Cardiff drained his at a jolt, and went to sit next to Elias Culpepper.

Culpepper puffed smoke. ‘We have,’ he said, seeming to consider his words with care, ‘sent all the children away to school.’

Cardiff stared. ‘The whole town? Every child?’

‘That’s the sum. It’s a hundred miles to Phoenix in one direction. Two hundred to Tucson. Nothing but sand and petrified forest in between. The children need schools with proper trees. We got proper trees here, yes, but we can’t hire teachers to teach here. We did, at one time, but they got too lonesome. They wouldn’t come, so our children had to go.’

‘If I came back in late June would I meet the kids coming home for the summer?’

Culpepper held still, much like Claude.

‘I said—’

‘I heard.’ Culpepper knocked the sparking ash from his pipe. ‘If I said yes, would you believe me?’

Cardiff shook his head.

‘You implying I’m a mile off from the truth?’

‘I’m only implying,’ Cardiff said, ‘that we are at a taffy pull. I’m waiting to see how far you pull it.’

Culpepper smiled.

‘The children aren’t coming home. They have chosen summer school in Amherst, Providence, and Sag Harbor. One is even in Mystic Seaport. Ain’t that a fine sound? Mystic. I sat there once in a thunderstorm reading every other chapter of Moby-Dick.’

‘The children are not coming home,’ said Cardiff. ‘Can I guess why?’

The older man nodded, pipe in mouth, unlit.

Cardiff took out his notepad and stared at it.

‘The children of this town,’ he said at last, ‘won’t come home. Not one. None. Never.’

He closed the notepad and continued: ‘The reason why the children are never coming home is,’ he swallowed hard, ‘there are no children. Something happened a long time ago, God knows what, but it happened. And this town is a town of no family homecomings. The last child left long ago, or the last child finally grew up. And you’re one of them.’

‘Is that a question?’

‘No,’ said Cardiff. ‘An answer.’

Culpepper leaned back in his chair and shut his eyes. ‘You,’ he said, the smoke long gone from his pipe, ‘are an A-1 Four Star Headline News Reporter.’

TWELVE (#ulink_2ab5db1e-3eec-54d9-9e42-24652f4fed65)

‘I …,’ said Cardiff.

‘Enough,’ Culpepper interrupted. ‘For tonight.’

He held out another glass of bright amber wine. Cardiff drank. When he looked up, the front screen door of the Egyptian View Arms tapped shut. Someone went upstairs. His ambiance stayed.

Cardiff refilled his glass.

‘Never coming home. Never ever,’ he whispered.

And went up to bed.

Sleep well, someone said somewhere in the house. But he could not sleep. He lay, fully dressed, doing philosophical sums on the ceiling, erasing, adding, erasing again until he sat up abruptly and looked out across the meadow town of thousands of flowers in the midst of which houses rose and sank only to rise again, ships on a summer sea.

I will arise and go now, thought Cardiff, but not to a bee-loud glade. Rather, to a place of earthen silence and the sounds of death’s-head moths on powdery wings.

He slipped down the front hall stairs barefoot and once outside, let the screen door tap shut silently and, sitting on the lawn, put on his shoes as the moon rose.

Good, he thought, I won’t need a flashlight.

In the middle of the street he looked back. Was there someone at the screen door, a shadow, watching? He walked and then began to jog.

Imagine that you are Claude, he thought, his breath coming in quick pants. Turn here, now there, now another right and—

The graveyard.

All that cold marble crushed his heart and stopped his breathing. There was no iron fence around the burial park.

He entered silently and bent to touch the first gravestone. His fingers brushed the name: BIANCA SHERMAN BATES

And the date: BORN, JULY 3, 1882

And below that: R.I.P.

But no date of death.

The clouds covered the moon. He moved on to the next stone.

WILLIAM HENRY CLAY

1885—

R.I.P.

And again, no mortal date.

He brushed a third gravestone and found:

HENRIETTA PARKS

August 13, 1881

Gone to God

But, Cardiff knew, she had not as yet gone to God.

The moon darkened and then took strength from itself. It shone upon a small Grecian tomb not fifty feet away, a lodge of exquisite architecture, a miniature Acropolis upheld by four vestal virgins, or goddesses, beautiful maidens, wondrous women. His heart pulsed. All four marble women seemed suddenly alive, as if the pale light had awakened them, and they might step forth, unclad, into the tableau of named and dateless stones.

He sucked in his breath. His heart pulsed again.

For as he watched, one of the goddesses, one of the forever-beautiful maidens, trembled with the night chill and shifted out into the moonlight.

He could not tell if he was terrified or delighted. After all, it was late at night in this yard of the dead. But she? She was naked to the weather, or almost; a mist of silk covered her breasts and plumed around her waist as she drifted away from the other pale statues.

She moved among the stones, silent as the marble she had been but now was not, until she stood before him with her dark hair tousled about her small ears and her great eyes the color of lilacs. She raised her hand tenderly and smiled.

‘You,’ he whispered. ‘What are you doing here?’

She replied quietly, ‘Where else should I be?’

She held out her hand and led him in silence out of the graveyard.

Looking back he saw the abandoned puzzle of names and enigma of dates.

Everyone born, he thought, but none has died. The stones are blank, waiting for someone to date their ghosts bound for Eternity.

‘Yes?’ someone said. But her lips had not moved.

And you followed me, he thought, to stop me from reading the gravestones and asking questions. And what about the absent children, never coming home?

And as if they glided on ice, on a vast sea of moonlight, they arrived where a crowd of sunflowers hardly stirred as they passed and their feet were soundless, moving up the path to the porch and across the porch, and up the stairs, one, two, three floors until they reached a tower room where the door stood wide to reveal a bed as bright as a glacier, its covers thrown back, all snow on a hot summer night.

Yes, she said.

He sleepwalked the rest of the way. Behind him, he saw his clothes, like the discards of a careless child, strewn on the parquetry. He stood by the snowbank bed and thought, One last question. The graveyard. Are there bodies beneath the stones? Is anyone there?

But it was too late. Even as he opened his mouth to question, he tumbled into the snow.

And he was drowning in whiteness, crying out as he inhaled the light and then out of the rushing storm, a warmness came; he was touched and held, but could not see what or who held him, and he relaxed, drowned.

When next he woke, he was not swimming but floating. Somehow he had leaped from a cliff, and someone with him, unseen, as he soared up until lightning struck, tore at him in half terror, half joy, to fall and strike the bed with his entire body and his soul.

When he awoke again, the storm over, and the flying gone, he found a small hand in his, and without opening his eyes he knew that she lay beside him, her breath keeping time with his. It was not yet dawn.

She spoke.

‘Was there something you wanted to ask?’

‘Tomorrow,’ he whispered. ‘I’ll ask you then.’

‘Yes,’ she said quietly. ‘Then.’

Then, for the first time, it seemed, her mouth touched his.

THIRTEEN (#ulink_c5654963-f2e1-5c21-ab92-fe9c35dd297d)

He awoke to the sun pouring in through the high attic window. Questions gathered behind his tongue.

Beside him, the bed was empty.

Gone.

Afraid of the truth? he wondered.

No, he thought, she will have left a note on the icebox door. Somehow he knew. Go look.

The note was there.

Mr Cardiff:

Many tourists arriving. I must welcome them.

Questions at breakfast.

Nef.

Far off, wasn’t there the merest wail of a locomotive whistle, the softest churn of some great engine?

On the front porch, Cardiff listened, and again the faint locomotive cry stirred beyond the horizon.

He glanced up at the top floor. Had she fled toward that sound? Had the boarders heard, too?

He ran down to the rail station and stood in the middle of the blazing hot iron tracks, daring the whistle to sound again. But this time, silence.

Separate trains bringing what? he wondered.

I arrived first, he thought, the one who tries to be good.

And what comes next?

He waited, but the air remained silent and the horizon line serene, so he walked back to the Egyptian View Arms.

There were boarders in every window, waiting. ‘It’s all right,’ he called. ‘It was nothing.’

Someone called down from above, quietly, ‘Are you sure?’

FOURTEEN (#ulink_54c91879-7fd1-5d9e-809e-6faaf0b72bb6)

Nef was not at breakfast, or lunch, or dinner.

He went to bed hungry.

FIFTEEN (#ulink_c3b269e2-ca6c-517d-876e-f80e6be79b63)

At midnight the wind blew softly in the window, whispering the curtains, shadowing the moonlight.

There, far across town, lay the cemetery, immense white teeth scattered on a meadow of fresh moon-silvered grass.

Four dozen stones dead, but not dead.

All lies, he thought.

And found himself halfway down the boarding house stairs, surrounded by the exhalations of sleeping-people. There was no sound save the drip of the ice pan under the icebox in the moonlit kitchen. The house brimmed with lemon and lilac illumination from the candied windows over the front entrance.

He found himself on the dusty road, alone with his shadow.

He found himself at the cemetery gate.

In the middle of the graveyard, he found a shovel in his hands.

He dug until …

There was a hollow thud under the dust.

He worked swiftly, clearing away the earth, and bent to tug at the edge of the coffin, at which moment he heard a single sound.

A footstep.

Yes! he thought wildly, happily.

She’s here again. She had to come find me, and take me home. She …

His heartbeat hammered and then slowed.

Slowly, Cardiff rose by the open grave.

Elias Culpepper stood by the iron gate, trying to figure out just what to say to Cardiff, who was digging where no one should dig.

Cardiff let the spade fall. ‘Mr Culpepper?’

Elias Culpepper responded. ‘Oh God, God, go on. Lift the lid. Do it!’ And when Cardiff hesitated, said, ‘Now!’

Cardiff bent and pulled at the coffin lid. It was neither nailed nor locked. He swung back the lid and stared down into the coffin.

Elias Culpepper came to stand beside him.

They both stared down at …

An empty coffin.

‘I suspect,’ said Elias Culpepper, ‘you are in need of a drink.’

‘Two,’ said Cardiff, ‘would be fine.’

SIXTEEN (#ulink_979e930c-972e-5b10-89b7-d1419c7503e8)

They were smoking fine cigars and drinking nameless wine in the middle of the night. Cardiff leaned back in his wicker chair, eyes tight shut.

‘You been noticing things?’ inquired Elias Culpepper.

‘A baker’s dozen. When Claude took me on the bread and muffin tour I couldn’t help but notice there are no signs – anywhere – for doctors. Not one funeral parlor that I could see.’

‘Must be somewhere,’ said Culpepper.

‘How come not in the phone book yellow pages? No doctors, no surgeons, no mortuary offices.’

‘An oversight.’

Cardiff studied his notes.

‘Lord, you don’t even have a hospital in this almost ghost town!’

‘We got one small one.’

Cardiff underlined an entry on his list. ‘An outpatient clinic thirty feet square? Is that all that ever happens, so you don’t need a big facility?’

‘That,’ said Culpepper, ‘would about describe it.’

‘All you ever have is cut fingers, bee-stings, and the occasional sprained ankle?’

‘You’ve whittled it down fine,’ said the other, ‘but that’s the sum. Continue.’

‘That,’ said Cardiff, gazing down on the town from the high verandah, ‘that tells why all the gravestones are unfinished and all the coffins empty!’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/rey-bredberi/now-and-forever/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Рэй Дуглас Брэдбери

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Фэнтези про драконов

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Two dazzling novellas from the celebrated author of Fahrenheit 451.Two previously unpublished novellas comprise this astonishing new volume from one of science fiction′s greatest living writers. In the first, ′Somewhere a Band is Playing′, newsman James Cardiff is lured through poetry and his fascination with a beautiful and enigmatic young woman to Summerton, Arizona. The small town′s childless population hold an extraordinary secret which has been passed on for thousands of years unbeknownst to the rest of human civilization.In the second novella, ′Leviathan ′99′, the classic tale of Herman Melville′s ‘Moby Dick’ is reborn as an interstellar adventure. It recounts the exploits of the mad Captain Ahab, who, blinded by his first encounter with a gigantic comet called ′Leviathan′, pursues his lunatic vendetta across the universe. Born in space and seeking adventure in the skies, astronaut Ishmael Jones joins the crew aboard the Cetus 7 and quickly finds his fate in the hands of an indefatigable captain.Published together for the first time in one volume, these two stories twinkle with Bradbury′s characteristically intricate metaphors and lyrical phrases. Both are a lasting testament to an older generation of writers that, much like the Leviathan itself, are on the threshold of passing on into the realm of legend.