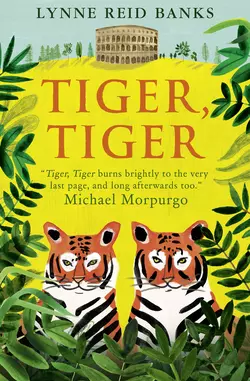

Tiger, Tiger

Lynne Banks

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Детская проза

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 697.37 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Two tigers. One city. Two very different lives.A compelling story about friendship, brotherhood and battling against the odds.In Ancient Rome Caesar is almighty and his power is played out in the gladiatorial arena, where animals and men are baited, challenged and destroyed.Two tiger cubs have been kidnapped from the jungle. One is tamed and de-clawed for pampered life as an exotic pet for Aurelia, Caesar′s daughter, but the other is cruelly caged and made even more brutal, trained to fight and kill.Princess Aurelia loves her pet tiger, Boots, and grows ever more fond of his keeper, Julius. But when a childish prank goes awry, Boots escapes. Furious Caesar sentences Julius to death in the arena… and Boots is to face the same fate.So the two tigers are reunited in the gladiatorial ring, one a cosseted pet, the other a vicious predator. In a world dominated by Caesar′s will, all must fight for freedom.