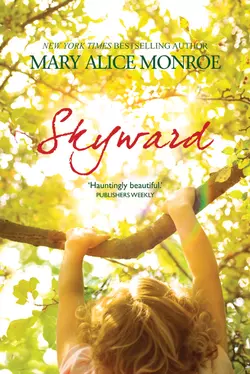

Skyward

Мэри Элис Монро

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 458.46 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Mary Alice Monroe returns to the captivating and mystical South Carolina Lowcountry, a place of wild beauty and untamed hearts, to tell the moving story of healing, hope and new beginnings…. E.R. nurse Ella Majors has seen all the misery that she can handle. Burned-out and unsure of her next step, she accepts the temporary position as caregiver to Marion Henderson, a frightened five-year-old who suffers from juvenile diabetes.But Ella soon realizes there is more sorrow in the isolated home than the little girl’s illness. Harris Henderson, a single father, seems better able to deal with the wild birds he rehabilitates in his birds-of-prey sanctuary than with his own daughter.Then something magical begins to happen: the timeless beauty of the South Carolina coast and the majestic grace of the wild birds weave a healing spell on the injured hearts at the sanctuary. But a troubled mother′s unexpected return will test the fragile bonds of trust and new love, and reveal the inherent risks and exhilarating beauty of flying free."A fascinating, emotion-filled narrative that′s not to be missed." –Booklist starred review «Monroe is in her element when describing the wonders of nature and the ways people relate to it…. Hauntingly beautiful.»–Publishers Weekly