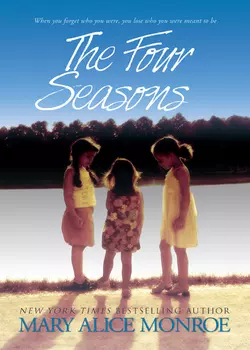

The Four Seasons

Mary Alice Monroe

They are the Season sisters, bound by blood, driven apart by a tragedy.Now they are about to embark on a bittersweet journey into the unknown-an odyssey of promise and forgiveness, of loss and rediscovery. Jillian, Beatrice and Rose have gathered for the funeral of their younger sister, Meredith. Her death, and the legacy she leaves them, will trigger a cross-country journey in search of a stranger with the power to mend their shattered lives.As the emotions of the past reverberate into the present, Jillian, Beatrice and Rose search for the girls they once were, in hopes of finding what they really lost: the women they were meant to be.

Praise for the novels of

Mary Alice Monroe

“Mary Alice Monroe writes from her heart to the hearts of her readers. It is a quality of emotional honesty together with lyrical, descriptive passages that draws her audience to books like The Four Seasons.”

—Charleston Post & Courier

“With novels like this one and The Book Club, Mary Alice Monroe continues to be one of the leaders of complex female relationship dramas that hit home to the audience.”

—Midwest Book Review on The Four Seasons

“Monroe writes with a crisp precision and narrative energy that will keep them turning the pages. Her talent for infusing her characters with warmth and vitality and her ability to spin a tale with emotional depth will earn her a broad spectrum of readers, particularly fans of Barbara Delinsky and Nora Roberts.”

—Publishers Weekly on The Four Seasons

“An inspirational tale of redemption.”

—Publishers Weekly on Swimming Lessons

“Monroe makes her characters so believable, the reader can almost hear them breathing…. Readers who enjoy such fine southern voices as Pat Conroy will add the talented Monroe to their list of favorites.”

—Booklist on Sweetgrass

“[A] spinning poignant and ultimately hopeful tale of forgiveness, family secrets and finding your way back home.”

—Bookreporter on Sweetgrass

“Skyward is a soaring, passionate story of loneliness and pain and the simple ability of love to heal and transcend both. Mary Alice Monroe’s voice is as strong and true as the great birds of prey of whom she writes.”

—New York Times bestselling author Anne Rivers Siddons

“Monroe’s novel is a fascinating, emotion-filled narrative that’s not to be missed.”

—Booklist on Skyward (starred review)

“With its evocative, often beautiful prose and keen insights into family relationships, Monroe’s latest is an exceptional and heartwarming work of fiction.”

—Publishers Weekly on The Beach House (starred review)

“With each new book, Mary Alice Monroe continues to cement her growing reputation as an author of power and depth. The Beach House is filled with the agony of past mistakes, present pain and hope for a brighter future.”

—Romantic Times BOOKreviews

“The Book Club skillfully weaves the individual story threads into a warm, unified whole that will appeal to readers who enjoy multifaceted relationship novels with strong women protagonists.”

—Library Journal

“Reflects the shadows and shapes of a woman’s painful and illuminating journey of self-discovery, of choices, of loves.”

—New York Times bestselling author Nora Roberts

on Girl in the Mirror

“Monroe draws you into an absorbing tale of hard-won success, devastating choices and the triumphant power of love.”

—Diane Chamberlain on Girl in the Mirror

The Four Seasons

Mary Alice Monroe

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

For my beloved sisters,

Marguerite, Ruth, Maureen and Nuola

All things have their season,

And a season for every purpose under heaven.

—Ecclesiastes 3:1

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Epilogue

Questions for Discussion

1

ROSE SEASON STOOD AT THE threshold of her sister’s bedroom and silently watched the shadows of an oncoming storm stretch like plum-colored talons across the empty bed. A great gust of icy wind from Lake Michigan howled at the windows.

“Merry,” she whispered with longing. Rose resisted the urge to open the window and call out to her in the vast darkness. Merry’s presence was palpable tonight. Rose had read somewhere that the spirit lingered for three days after death. Merry had been dead for four. Did she tarry to be sure her last request was honored?

Her last request. Why had she agreed to it? Rose asked herself, wringing her hands. The request was crazy, intrusive, maybe even hurtful. No one would ever go along with it. What would her sisters do when they read Merry’s letter? Especially Jilly. She’d never spoken of that time, not once in over twenty-five years. It was as though it had never happened. She’ll be furious, Rose worried. But secrets in families always had a way of coming out in the end, didn’t they?

The hall clock chimed the hour. Rose tilted her head, thinking to herself that she should be calling Merry for dinner now, telling her to wash up. A pang of loneliness howled through her like the wind outside. She wandered into Merry’s lavender room, idly running her fingers along the girlish white dresser, the dainty vanity table and the silver-plated brush, comb and mirror set. Strawberry-blond hairs still clung to the bristles. Across the room, she bent to pick up the ratty red-haired baby doll lying in the center of the pristine four-poster bed. How Merry had loved the baby doll. Spring, she’d called it, and never once in twenty-six years slept without it. Rose brought the doll to her cheek, catching Merry’s scent still lingering in the fabric. Then, with a loving pat, she placed the doll back on the bed, careful to prop it against the pillow. Rose’s hands felt uncomfortably idle. She smoothed the wrinkles from the comforter with agitated strokes, then moved to the bedside stand to straighten the lace doily, adjust the pleated lampshade and line up the many small bottles of prescription drugs that she was so familiar with. She couldn’t part with anything of Merry’s yet, not even these medicines.

Without Merry to take care of, she felt so useless and detached in the old house, like the shell of a cicada clinging worthlessly to the bark. She needed work to keep her going, some focus to draw her attention from her mourning. With a discipline that was the backbone of her nature, Rose walked swiftly from the gloomy bedroom to the wide, curving staircase of the old Victorian that had been her home since she was born.

The walls along the stairs were covered with dozens of photographs of the Season sisters at various moments of glory and achievement in their lives. For comfort, she glanced at the familiar photographs, treasuring the faces captured in them: Jilly, Birdie, Rose and Merry. The Four Seasons, their father had called them. The largest numbers of photographs were of Jilly and Birdie, the eldest two. There were fewer pictures of Rose, and hardly any of Merry, the baby. She longed for her sisters; it had been nearly ten years since they had all been together. How sad that it took a funeral to bring them together again.

Who would arrive home first? she wondered. Birdie was extremely busy with her medical practice in Wisconsin, but Jilly had the farthest to come—all the way from France.

Rose paused at a framed 1978 Paris Vogue magazine cover that showcased a young Jillian at twenty-one years of age, looking sex-kittenish in a fabulous pink gown that clashed in a chic way with her vibrant red hair. It was her first cover. Rose studied her eldest sister’s full red lips pursed in an innocent pout, her deep-set eyes of emerald-green and the come-hither pose exposing one long, shimmering leg that seemed to go on forever. She couldn’t imagine herself ever standing in front of so many people, in the glare of the lights, while men snapped her photograph. For that matter, Rose couldn’t imagine ever looking so seductive or desirable.

Jilly was born at 12:01 a.m. on November 1, 1955. All Souls’ Day. Mother always told of how she’d squeezed herself shut because she didn’t want a child of hers born on Halloween. Who knew what nickname father would have chosen then? Their father, William, claimed it was a family tradition to play with their unusual last name. After all, he was nicknamed Bill Season. But their mother, Ann, a petite beauty with a will of iron, swore no child of hers was going to be tagged for life with a name people laughed at. As a compromise, Ann Season gave her daughters strong, sensible names, allowing their father full rein with the nicknames. Thus for his first daughter, Jillian, born in a Chicago autumn, he thought himself clever to name her “Jilly Season.”

Moving down the stairs, Rose perused the large collection of photographs of Beatrice. Jilly liked to be first, but in most things Birdie came through for the prize. “The early bird catches the worm,” their father used to say with a wink of pride at his second daughter. Birdie was his favorite, everyone knew that. Jilly would tease her and say Birdie was the son he never had. She was a tall, broad-shouldered girl with a powerful intellect and an even more powerful, competitive spirit. Even the name “Birdie” seemed to mock her tomboyish body.

Bill Season had chosen the nickname because she was born in early summer and was insatiable, howling for more food like a hungry bird in the nest. And she’d certainly caught the worms, Rose thought as her gaze wandered over the photographs. The first was Birdie at sixteen, beaming into the camera, dripping wet and clutching an enormous silver trophy for the state championship swimming team. She’d been the captain, of course. And there were more photographs, of Birdie as class valedictorian, of Birdie winning trophies for swimming, lacrosse and the science fair. Birdie receiving a diploma from medical school. Birdie dazzling in white lace and tulle smiling at her handsome groom, Dennis, the biggest trophy of all.

There were fewer pictures of herself, the third child. This section of wall seemed almost barren when compared to Birdie’s. Rose felt the usual flush of embarrassment that the scarcity of photographs was an accurate—if pitiful—statement about her life. It was all very well that Jilly was a famous model, on magazine covers all over Europe, and that Birdie was a successful doctor, wife and mother. But what about her own life? There was neither a photograph of her graduating from college, nor a picture of a radiant Rose on her wedding day. Her mile-marker was a high school graduation photograph that showed a thin, shy girl looking much like she did today.

Rose’s hair was a paler, washed-out version of the Season red that her father playfully called “pumpkin” and her mother optimistically called “strawberry blond.” She still wore it in the same long, straight style of high school and her body was every bit as lean and shapeless as it been then. “Sticks,” the other children had called her. In all the pictures, her eyes were the dominant feature. Enormous hazel eyes with brows and lashes so pale they were seemingly not there. They peered out from her pale face, large and wary, like a cat’s when poised to leap away.

Rose was born in the dog days of August when her mother’s roses were blooming. Thus she was called Rose, the only one of the four Season girls without a nickname. Rose was a fine, plain name, her father had always said. And it suited her, she thought with a sigh of resignation.

As with most families, the baby had the fewest photographs. Which was too bad, she thought, since Merry was arguably the most beautiful of all the Season girls. Their parents had been older when they married and had had children late. Thus, their father liked to say that Merry was his last hurrah. The fourth Season. Meredith was born in December, a season ripe with nickname potential, but Bill had settled on “Merry” because she was such a cheerful baby. Rose traced a finger across a picture of a precocious, impish Merry at two years of age. The pictures stopped then.

Rose turned her head away from the photographs, closing her mind from the memory, and wandered from room to room, feeling that edginess that comes when one is aimlessly looking for something to do. Each of the twelve rooms of the Victorian was immaculate, a savory dinner was waiting in the oven and flowers were beautifully arranged in the bedrooms. She turned on the television, then as quickly flicked it off again. She picked up a book and settled into a comfortable chair, but no sooner had she read a paragraph than her mind wandered again. She closed the book in defeat and laid her head back against the chair. With a heavy sigh, she reached into her apron pocket and pulled out a pale blue envelope.

Merry’s letter.

She’d carried this letter in her pocket all day wondering whether to burn it or send it to the family lawyer. The moment of decision had come; the funeral was tomorrow. Rose closed her eyes and recalled how Merry’s pink tongue had worked her lip as she’d struggled with the letter, wanting it to be her best. Merry couldn’t have comprehended how those brief sentences, written in her childlike script, would send thundering repercussions in her sisters’ minds and hearts—as it had hers when she read them.

She looked down at the envelope in her hand and was moved to tears by the sight of the address painstakingly written in Merry’s handwriting, encircled by a big heart: To Jilly, Birdie and Rose.

She would give the letter to the lawyer, Rose decided. It was the right thing to do. Merry needed her—trusted her—to deliver it. This time she would not fail her.

Beatrice Season Connor looked up into the April sky and cursed.

“Look, it’s snowing!” Hannah called, stepping out from the car. Her fifteen-year-old daughter’s face turned upward, and with a delighted grin, she darted her tongue out to catch the soft, moist flakes as they tumbled gracefully from the sky.

“That’s just what we need. A snowstorm on top of everything else.”

“It’s just a few flakes.” Hannah’s voice was full of reproach.

“From the looks of it, we’re going to get a dump. Damn snow,” Birdie muttered, grabbing the bags full of last-minute shopping items from the car and hoisting them into her strong arms. “I’m sick of snow. Hasn’t Milwaukee had enough for one year? It’s April, for crying out loud. Well, that’s it,” she said with the quick decision typical of her. Slamming the door, she headed toward the house. “We’re going to have to hustle and leave for Evanston earlier than we’d planned if we expect to get everything done by the funeral.” She stopped at the door and turned to face her daughter. “I’m counting on you, Hannah. I’m going to need your help.”

“I don’t see why we have to do everything.” Hannah crossed her arms over her chest.

“We do if we want it done right.” Birdie privately groaned at the prospect. The notion of pushing forward her departure when her schedule was already jammed full thrummed in her temples. She was squeaking out of town as it was. Sometimes she felt like a circus performer twirling countless plates: she had had to arrange coverage for her medical practice, calm her patients, take the dog to the kennel, cancel the housecleaning service, pack…The list went on and on. On top of all that, the funeral was tomorrow and it was up to her to make certain everything ran smoothly.

“When you need something done, ask a busy woman,” she murmured with a heavy sigh, though secretly she felt a superior conceit. To her mind, all it took to succeed was discipline, setting goals and lots of hard work. And she worked harder than most. She could list her achievements readily: she was a pediatrician with a thriving practice, a wife for nineteen years, the mother of a healthy daughter and the mistress of a large, well-managed home. If there was such a thing as a supermom, Birdie thought with pride, then she was it.

But today was a test of her abilities. She lifted her wrist to check her watch and her lips tightened with annoyance. God, look at the time. Where was Dennis? And Hannah? Peering outside, she saw Hannah still leaning against the rear fender, gazing at the twirling flakes of snow. Frustration brought the pounding in her head to a painful pace.

“Didn’t you hear me say we were leaving early?” she called from the back door.

Hannah’s smile fell but she remained motionless, resolutely staring out.

“Don’t pull that passive-aggressive act on me, young lady,” she called, raising her voice as she walked nearer the car. She could feel her anger growing with each step. “I’ve asked you to get your packing done for twenty-four hours and so far you haven’t done a thing. I’m not going to do it for you.”

“Who’s asking you to?” Hannah swung her head around. “You’d just pack the wrong things, anyway.”

“This isn’t a prom we’re talking about. It’s my sister’s funeral. My baby sister! It’s hard enough for me to deal with the fact that she’s gone without having to argue about meaningless things like your dress.”

“At least you have a sister.”

Birdie felt the weight of that reply start to drag her under. How many years had she had this thrown in her face like a broken promise? “Hannah, please. We don’t have time to argue. Just go upstairs and pack a black dress,” she ground out with finality.

“You never ask me to do something, you order me. Yes, you do! I hate you!” she shouted when Birdie opened her mouth to object. Hannah fled into the house, slamming the door behind her.

Birdie knew that those words were spoken in the white-hot fire of teenage anger and flung at her to burn—and burn they did. A mother never hears the words “I hate you” without cringing and feeling like a hopeless failure.

She followed Hannah back into the house with a heavy tread. Closed doors were a way of life between them now. Why did push always come to shove between them? And when had she started to feel the need to win these senseless battles? Not so long ago, she’d let trivial arguments slide by because all the parenting articles she’d read had a unified rallying cry: choose your battles! With teenagers, however, everything was a battle.

She walked to the small desk in the kitchen and worked away her frustration by cleaning up the day’s disorder. When all was spotless and organized, she reached for a stack of patient messages awaiting her. Clearing her mind of personal problems, she picked up the first one and dialed.

An hour later, she was just finishing up her last call when her husband walked in from the garage. She turned her head to see Dennis shake off a covering of powdery snow from his lambskin jacket. He was five foot ten, just an inch taller than she was, but his build was slight in line and breadth of bone. With his long, thoughtful face, his dark brown eyes behind round, tortoiseshell glasses, his blond hair worn shaggy to the collar and his rumpled corduroy trousers worn with a sweater rather than a jacket, he looked every inch the university professor that he was.

He kicked the snow from his shoes. When he looked up, she noted that his face was pale and pinched from fatigue. He used to smile and call out a cheery “I’m home!” Lately, however, he entered the house in silence. Birdie frowned with concern, then turned her focus back to the patient on the phone.

“No, Mrs. Sandler, Tommy doesn’t need an antibiotic. Yes, I’m sure. He doesn’t have a bacterial infection. It’s a virus, though a nasty one. No, an antibiotic won’t help. In fact, it would weaken his natural resistance.” Birdie caught Dennis’s eye and held up her finger for him to wait a minute. Dennis nodded, flung his coat over the edge of the kitchen chair, then reached into the fridge for a beer.

“Keep a close eye on him, and if he takes a turn for the worse or spikes another fever, then call my office. Dr. Martin is covering for me. What? Ninety-eight point six is normal.” She rolled her eyes and reached out for Dennis’s beer. “Yes, very good. Bye now.”

Birdie sighed with relief, placed the receiver back on the hook, then tossed back her head and took a long swig of the beer. “Diagnosis—worried parent,” she muttered.

“Tough day?”

“The worst. It started off with the dog being sick. He’s so damn neurotic every time he has to go to the kennel. Hannah’s been her usual petulant self. Then the patients started in.” She lifted the thick stack of yellow messages.

“I thought you arranged coverage.”

“I did, but you know there are always those patients who panic when I leave town. It’s just easier for everyone if I call them.”

“You don’t have to go that extra mile. No one else’s patients expect such service. I don’t know why you have to push yourself so hard. You’re already better than most docs out there.”

“I’m better because I’m compulsive about such things. It’s who I am. Anyway, the point’s moot because I’m all done. That was the last of the calls, thank God.” She tossed the yellow slips into the trash.

“So, you’re free.”

She smirked. “Free to go home and run a funeral.” Dennis set his beer down on the counter and lifted his hands to her shoulders, a familiar gesture that Birdie welcomed. She sighed and leaned into him, slumping in relief the moment his hands began massaging. He had wonderful hands, long-fingered and strong; he could knead knots out of her shoulders like no one else. They’d started dating in college when she was a champion swimmer for the team. He used to massage her shoulders after her swim meets. She still teased him that she married him for his hands.

“God, that feels good,” she groaned.

“You’re all knotted up. You need to relax.” He leaned closer and said in a seductive tone by her ear, “I know what will loosen you up. When do we have to leave?”

Birdie cringed and moved out from under his hands. The last thing she was interested in right then was sex and she was irked that Dennis would even think she would be. “For God’s sake, Dennis, we have to leave in forty minutes.”

Dennis held his hands in the air for a moment, then let them drop to his sides with resignation. When he spoke, his voice was lackluster. “I thought we weren’t leaving till four.”

“Did you forget we’re supposed to pick up Jilly from O’Hare?” Her exasperation rang in her voice. He could remember the dates of every foreign war the United States was ever in, but he never seemed capable of remembering one family date on the calendar. “If this front becomes the storm the weathermen predict, traffic will be snarled up all along the interstate and Jilly’s flight will be delayed, if not canceled. Who knows what time she’ll get in? It’s crazy for us to pick her up. We could sit there for hours.”

“So why doesn’t Rose pick her up?”

Birdie snorted and shook her head. “I’m not even sure Rose knows how to get to the airport. She never leaves Evanston, and as far as I can tell she rarely leaves the house! She doesn’t much care for talking on the phone, either. She screens calls on the answering machine before picking up. Who does she think is going to call her, anyway? She doesn’t have any friends. Rose is a dear heart but I swear she’s becoming more and more isolated every year.”

Birdie rubbed the stiffness in her neck. After the funeral was over and the family house was sold, she’d have to have a serious talk with her sister about her future. Rose had to face up to leaving the house, and she’d have to get a full-time job, one that would support her. At least she had her computer skills. But Rose was such a stay-at-home she’d have a hard time making new friends and a new life. It wasn’t good that she had locked herself away as caretaker for Merry all those years.

“Tell Jilly to take a cab.”

“What? Oh yeah…well, I suggested that to her on the phone but she complained and reminded me how long it’d been since she’d been home and told me how much luggage she had and so on and so on. Get this. She wanted to be picked up by a family member—at the gate!”

His shook his head. “And you relented….”

“Who doesn’t with Jilly?”

“Well, even you can’t order a blizzard around.”

Birdie chuckled then pursed her lips, considering her options. Her first priority was to get to Evanston and make certain the funeral arrangements she’d spent hours—days—on the phone making were going smoothly. She rested her hands on the counter and leaned against them. “God, this is going to be a nightmare. Who knows what to expect from her? Do you remember the scene Jillian made at Mother’s funeral?”

He shrugged. “Jillian lives to make a scene. I don’t see what the commotion is about. She’ll arrive in a state, stay long enough to make another scene, then leave and we won’t see her for another ten years. God willing.”

“I don’t see why you dislike her so. She’s never done anything to you.”

“She doesn’t have to. It’s what she does to you that makes me dislike her.”

“What do you mean?” Birdie replied, genuinely surprised. Dennis never made any pretense over the fact that he didn’t like her more glamorous sister.

“She puts you on edge,” he replied, looking Birdie directly in the eye. “She makes you feel somehow less.” He lowered his gaze. “You’re not the same whenever she’s around.”

Birdie wanted to tell him that was because he was never the same when she was around. Dennis had dated Jilly for a brief period in high school, something Birdie never felt comfortable about. Neither of them ever mentioned it, but sometimes, when he didn’t think anyone was looking, she caught him gazing at Jilly with an odd expression on his face. She’d wondered if the gaze was merely speculative, or, and she shuddered to think this, if it was lust she saw under his heavy, hooded eyes.

“If she makes me feel less,” she replied, loading ice blocks into the cooler, “it’s only in the arena of beauty. Let’s face it. Jilly is gorgeous.”

“So are you.”

“No, I’m not.” She wasn’t being coy. Birdie knew that age and the additional twenty pounds that crept on over the past decade had not improved her already large frame. In the looks department, nothing she had could compare to Jilly. Birdie’s eyes were pale blue, not a vivid green like Jilly’s. All she had of the famous red Season hair were a few red highlights in the dull brown. Worst of all, she had her father’s nose. He told her to be proud of the aristocratic though slightly askew family inheritance, and in fact, she was. But it did nothing to enhance her beauty.

“You are to me.”

When he said things like that Birdie’s heart did a quick flip and she felt a sudden gush of love for him. She turned and busied her hands rinsing a few cups in the sink, flustered. “That’s sweet. But really, Dennis, I’m over forty years old and a success in my own right. I don’t need to pretend I’m beautiful for my self-esteem.”

Dennis just shook his head sadly.

She turned off the water and made a snap decision. “We’ll skip the airport. I’ll call Rose and see what else can be arranged. But we’ll still have to leave early in this storm. Where were you, anyway?” she asked, turning to face Dennis. “You said you’d be home by twelve.”

“What time is it now?”

“It’s almost three.”

He shrugged and raised his brows in a gesture of innocence. “I had a lot to do to leave town for several days. Midterm grades need to be averaged before spring break. Then there was an emergency meeting with the chairman.”

He loosened his tie and tugged it off with a frustrated yank. “I got out as quickly as I could.”

“Didn’t it occur to you that I’ve got a lot to do, too? While you were arranging your schedule, I was doing the same plus shopping for the trip, packing up and taking the dog to the kennel.”

He turned his back to her and grabbed the beer bottle from the counter along with the stack of mail. “Well, we can’t all be as efficient as you.”

She felt the sting of his words as she watched him lean casually against the counter and sift through the mail as though he had all the time in the world. He could be oblivious to everyone’s needs but his own, she thought. Hannah may not have inherited his lean physique, but she had certainly inherited his temperament.

“Where’s Hannah?” he asked, as though reading her mind.

“She’d better be upstairs packing. Would you go up and check on her? I’ve asked her to pack for two days and she hasn’t done it. Now we’ve run out of time and if she’s not done I guess I’ll have to do it.”

“No you don’t,” he replied, looking up from his mail. “If she leaves something out, then she’ll have to live with it.”

“Oh, Dennis, don’t be ridiculous. If I don’t get after her who knows what she’ll wear?”

“Then she’ll be embarrassed. You’re the one who’s always preaching about natural consequences.”

Birdie fumed. She knew he was right, but she just couldn’t bring herself to allow her daughter to be poorly turned out for her sister’s funeral. “Whenever someone sees a poorly dressed child, or walks into a messy house, they never blame the father. It’s always the mother who’s thought of as a slacker.”

“Who cares what anyone thinks?”

“I care!”

“You might as well relax and let her be. She’s fifteen. She’s not going to listen to anything you say, anyway.”

She put her hands up in an arresting position, cutting him off. “We’re not going to get into this right now. I’ve simply too much to do. Could you please just go upstairs and finish your own packing without this big discussion? I already packed your dark blue suit for the funeral. Just pick out some casual clothes. That’s all you have to do.”

“You never like what I pick out, anyway, so why not finish it yourself?” he muttered, but he shuffled up the stairs, anyway.

She bit back a retort and turned on her heel to head for the phone. If she didn’t get some space between them quickly the fuse they’d lit would explode. Lately, anytime they were in a room together it was like putting a match near a powder keg. The tension had really started heating up again in the past few days. Ever since Merry’s death.

Birdie paused to think, Was it only four days ago that Merry had died?

It was a night much like any other night. There had been no premonition of trouble to come. Birdie had always thought she would somehow sense when a loved one was dying, especially someone as close as a sister. She was a physician, after all. She expected that she’d develop some intuition as to when death was imminent. Apparently not, she thought, chagrined. She hadn’t suspected a thing as she crept under the sheets, yawned and murmured good-night to her husband before falling into a deep, undisturbed sleep.

The call from Rose woke her just after 11:00 p.m. Merry’s lungs had filled again with the current bout of flu and she was having trouble breathing. Complications weren’t unusual for Merry. Her lungs had been damaged as a child, making her a high-risk patient. Her doctor had upped her medication and was on his way but Rose wanted to call Birdie for help.

Birdie had risen promptly, dressed, made a pot of coffee and placed a call to her colleague to cover her morning appointments in case she was late getting back. It didn’t take long, not more than forty minutes, to get on the road. When she knocked on the door of the Season family home not even four hours later, Birdie had known instantly that she was too late. Rose met her with grief etched across her drawn face and red-rimmed eyes. Even in her shock, Birdie noticed the calm, even serene cadence to Rose’s voice.

Birdie, our Merry is gone. I know, I know…It was all very sudden and there was nothing that could be done. It caught all of us by surprise. It was her time and she was ready. There, there…It was peaceful, really it was. You know our Merry…. She died with a smile on her face.

Birdie reached a shaky hand up to wipe the tears from her cheek. That was four days ago and she still couldn’t believe her sister was dead. In her opinion, she was allowed to slip away. Rose should have called her to Evanston the minute Merry’s flu worsened. The doctor should have admitted her to the hospital at the first sign of fluid in the lungs. Fury, guilt and sorrow twisted in Birdie’s heart as she wrestled with the issue that kept her awake at night and shortened her temper during the day.

If only she had been faster—perhaps skipped making the phone call or that pot of coffee, if she’d pushed the speed limit on the way down—she might have been able to save her.

Jillian DuPres Cavatelli Rothschild Season reached above her head with a shaky hand and buzzed for the steward. Most of the other passengers were slowly becoming alert, having eaten and napped. But the plane was a mess. The stewards had done their best, but eight hours of togetherness was getting very old and the interior of the enormous plane looked as tired as the 178 passengers felt.

She buzzed for the steward once again. A handsome blond young man in a horrid navy-and-burgundy striped shirt sauntered down the narrow aisle to her seat and mustered a tired smile. He had long, curly lashes that any model would kill for, but from the looks of the circles under his eyes and his bored expression, he was more eager for this plane to land than she was.

“I’d like a Scotch, please,” she said, handing him money. “And some water and ice.”

He paused, furrowing his brows, seemingly trying to gather his last vestige of polite intervention. “We’ll be landing soon, ma’am. Perhaps some coffee?”

Jilly straightened in her seat and delivered one of her famous megawatt smiles. “If I wanted coffee,” she said in a honeyed voice, “I’d have asked for it. What I want is one of those cute, itty-bitty bottles of Scotch and a glass of ice with just a smidgen of water. Please.”

The steward looked severely uncomfortable now, glancing furtively at the old woman in the next seat who was hanging on every word. He stretched across the backs of the row ahead and said in a low, conspiratorial whisper, “You’ve had three already and you didn’t touch your dinner.”

Jilly leaned forward and replied in a stage whisper, “I know. I never eat anything I can’t identify.”

“Are you sure you wouldn’t want some coffee, or perhaps some tea?”

It was embarrassing enough to have to ride in coach again. In first class they wouldn’t have questioned her request. More Scotch? Right away!

Jilly dropped all pretense of friendliness. “What I’d like, young man, is a cigarette. But since you fucking well won’t let me have that, I’ll settle for a Scotch.” She turned to the elderly woman. “Excuse my French.”

She could tell from the way the steward’s lashes fluttered that the slim young man wanted to tell her what she could do with her fucking cigarette and Scotch. Jilly steeled herself, ready for a fight when the little bell went off and the pilot’s voice informed them that he was sorry but that there was heavy snowfall in Chicago and that there would be long delays. This was met with a chorus of groans from the passengers. The steward closed his eyes for a moment and took a breath. When he opened them again, he proffered a perfect steward’s polite smile that said, Forget it, it’s just not worth the aggravation.

“Right away, ma’am.”

Jilly watched him retreat down the aisle as a dozen more lights lit up and hands flagged him as he passed. She hated to be called ma’am, madam, frau or any other sobriquet that implied she was old. Still, she felt a twinge of regret for making such a fuss, but not so much that she didn’t want her drink.

A short while later the little bottle of Scotch was delivered, along with her five-dollar bill. Apparently the flight was in a holding pattern and drinks were on the house. Grumbles were still audible throughout the cabin but the gesture of goodwill went a long way to settle the passengers. “Thank you,” she said sweetly as she tucked the five-dollar bill into her purse. These days, every dollar counted.

“It’s been a long trip, hasn’t it,” the old woman beside her said in a sympathetic voice. She’d introduced herself as Netta. She was doll-like and positively ancient with waxy skin rouged in small circles over her cheekbones. Her eyes, however, were an animated blue that rivaled the sky Jilly had left in Paris.

Jilly could only nod, thinking how it would take longer than the endless eight-hour flight to explain to this woman the journey she’d traveled since she’d received the telephone call from Rose. Hell, just since her last smoke. Until the last boarding call she’d stood in the bar, puffing like a locomotive, storing up nicotine in her cells for the long trip like a camel would water. She’d been in agony anticipating her return to the old Victorian loaded with memories as ancient and musty as the velvet curtains and bric-a-brac. You can’t go home again, the old adage said. She wished it were true. For twenty-six years, she’d tried not to. But here she was, on a Boeing 747, doing just that. Everything she owned was squeezed into two large Louis Vuitton bags and stored in the belly of this plane. She’d had to borrow the money from a friend to purchase the ticket to Chicago—one-way coach.

“Are you all right?” the old woman asked kindly.

Jillian turned her head. She saw genuine concern in the bright blue eyes, not curiosity or annoyance at her fidgety behavior.

“I’m just tired,” she replied, taking her glass of Scotch in hand. “Thanks.”

“Is it your job? I read about stress on working women all the time.”

A short laugh escaped as Jilly shook her head. “No, not the job. Unfortunately.”

“What do you do, if you don’t mind my asking?”

“I’m a model.” She shrugged lightly. “And I was in a few foreign films.”

The woman’s eyes crinkled with pleasure. “I thought so. You’re very beautiful.”

The compliment washed warmly over Jilly and she smiled for the first time that day. “Not so ‘very’ anymore. I’m…retired.”

Her smile fell as she heard again the comments of the agencies. You are still a beautiful woman, but…You’re over forty. You know how it is…. Look at them, they are nineteen! So young!

She couldn’t blame them. Age was an occupational hazard of the beauty business.

“I’m too old,” Jillian said, finding it easy to confess to a stranger.

The elderly woman laughed lightly and shook her head. “How amusing. I was just thinking how I wished I was as young as you!” She reached out to pat Jilly’s hand. “You see how Einstein was right, my dear. Everything is relative.”

“By that you mean the grass is always greener, I suppose.” She didn’t want to add that she didn’t find that the least bit comforting.

“No,” the woman replied. “Actually I was referring literally to the theory of relativity. How different observers can describe the same event differently. From my position in the universe, my dear, you are young. And vibrant and beautiful. From your position, let’s see…” She raised a crooked finger with a tiny, yellowed nail and pointed.

“I suppose you see that child over there as young and beautiful, am I right?”

Across the aisle sat a twenty-some-year-old woman in jeans and a clinging shirt, devoid of makeup, with dewy skin and the firm muscle tone Jilly had lost long ago. Mouth pulling in a wry smile, Jilly nodded.

“You see? It’s all relative. Why do you think older women like to stick together? Because we see one another as beautiful and vibrant. I guess you could say we’re traveling at the same speed.” She laughed softly again, then added wistfully, “I wish someone had explained Einstein’s theory of relativity to me when I was young. It would have taught me to be more accepting, and probably more compassionate, to others’ points of view. That would have prevented a few troubles in the past, I can assure you. Take my word and remember this—how you see the world may not agree with how others see it. But you have to accept that their observations are valid. So,” she said with a light tap of her nimble fingers on Jilly’s hand, “you are young and beautiful, my dear, and nothing you say will convince me otherwise.”

Jilly smiled, conceding the point. “For me, relative means my sisters. And let me tell you, do we ever see the world from different positions.”

“Ah, you’re going to see your sisters?”

Jilly nodded. “Yes. Well, two of them. My third sister just passed away. It’s her funeral that brings me home.”

“Your older sister?”

“The youngest. She was the baby, just thirty-two when she died. She had bad lungs and they gave out.”

“Oh, that is sad. Death is always so, but an early death is more tragic. You have my sympathy. Funerals can be very emotional, you know. Use this time to gather your strength.” With another gentle pat, the older woman turned her attention back to her book.

Jilly shifted in her seat. As she watched the amber-colored fluid swirl around little chunks of ice, her mind stumbled over thoughts of Merry. Dear little Merry, gone. She swallowed the Scotch and relished the smooth burn. It was strange to think of her thirty-two-year-old sister as little, but that’s how she always thought of Merry. Poor, poor Merry…Whenever Jilly looked into those sparkling, childlike eyes, she felt a stab of guilt in her abdomen so painful it drove her an ocean away.

Yet here she was, crossing that same ocean again. It was poetic justice that she was stuck in a holding pattern over O’Hare, she thought, twirling the ice, since her mind was going round and round the same old stories, the same old issues. Thirty years of circling…

Her thoughts were interrupted by the voice of the captain.

“Ladies and gentlemen, good news. The runway at O’Hare has been cleared and we’ve been given permission to land. Thank you for your patience. Please return to your seats and fasten your seat belts. Stewards, prepare for landing.”

The sigh of relief was audible in the plane. Taking a deep breath, Jilly pulled her large Prada bag from under the seat and reached for her makeup. Polishing her face was second nature to her. It was an armor against an unfriendly world. In her compact mirror she saw the familiar green eyes staring back at her. They were once described as bedroom eyes, but now they were simply tired and hardened by experience. She dabbed at the mascara smudges under her eyes and smoothed blush onto her cheeks. Though still creamy and smooth, her skin was far from dewy. She stared at her face a moment longer, hating it.

Her move to Europe may have lessened the emotional intensity with distance, but it was never the cure. Each mile closer, each moment nearer to landing, she could feel the turbulence of her emotions rise closer to the surface.

After thirty years, Jillian Season was coming home to stay.

2

A HELLO BURST FROM ROSE’S LIPS as she swung the door wide to see Birdie, her nose red and her head tucked into her coat collar like a turtle.

“Come in! Come in, at last!” Rose cried out, feeling a heady joy and hugging Birdie tightly, relishing the feel of her sister’s arms around her, padded as they were by her thick coat. Birdie dwarfed Rose as she engulfed her in a long, firm embrace. Instantly they were ageless, bound by a shared childhood and years of history.

“Mother, I’m freezing!” cried Hannah.

The sisters laughed and stepped aside as the wind gusted, sending a spray of icy crystals in their faces. Rose shivered but held the door for Hannah, then waited for Dennis as he huffed and puffed up the stairs with the suitcases. Rose thought their faces were travel-weary as they filed past and she sensed a tension between them, as though they’d been arguing. She notched up her cheeriness, closing the heavy oak door behind them against the cold. They stomped the snow from their boots and slipped out of their coats and gloves, all the while delivering bullets of reports on the journey. Boy-oh-boy what a trip…back-to-back traffic…one accident after another…slippery…damn tollbooth backed up for miles.

Rose led them into the living room, where soft halos of yellow light from the lamps created a welcoming warmth and the scent of her roast beef and garlic permeated the wintry air. Vivaldi’s Four Seasons played softly in the background—a family favorite.

On the table cheese, crackers and crudités, looking a bit tired after the long wait, awaited on silver trays. She was proud of her efforts to make the house comfortable, pleased to see the tension ease from their faces and color suffuse their cheeks.

“So many flowers!” Birdie exclaimed, eyes wide as she walked from table to table admiring the arrangements and pausing to read the cards.

“More come every day. Merry’s doctors, the neighbors, old friends of Mom and Dad’s, they all sent something. I didn’t know so many people cared about her. She didn’t see people much, but she obviously made an impression. I only wish she were here to enjoy them,” Rose added wistfully.

“Aunt Merry loved flowers,” Hannah ventured solemnly.

Rose nodded, noting the sullen expression on her niece’s face.

Birdie’s face was passive as she walked around the large living room, taking in the familiar twelve-foot ceilings, turrets, molding, quaint panes of glass and gorgeous woodwork. It was a shame, she thought, how far from grace this room had fallen. Growing up, the room had been a showcase of the craftsmanship of an age past. Now it was a gloomy house, muted, shuttered, even shabby. It was far too big a house—too expensive—for Rose and Merry to have lived in alone. It all but bled Merry’s trust fund dry. Several times she’d suggested that they sell it and move into a small, more manageable house. But that was unthinkable to Rose. She’d claimed Merry would be too upset to move and argued, rightfully, that private hospitals or homes would be as expensive, if not more. In truth, she knew the prospect of leaving the family home filled Rose with as much horror as it did Merry.

And Rose deserved every consideration. She certainly took her duty as caretaker to heart. The house, though falling down around their ears, was spotlessly clean. The brass fixtures gleamed, the wood was polished and smelled of soap, and all the beveled glass on the cabinets and the grand crystal chandelier sparkled. Yet with her mind on putting the house on the market, Birdie was looking at it with a cold and practical eye. They’d certainly have a lot of work to do before selling it.

“Would you like a glass of wine?” Rose asked, eager to make them comfortable. “Water? You all must be parched. Hannah, how about a Coke? Dennis?”

“A beer would be great if you’ve got it,” he replied, rubbing his hands.

“Nothing for me. I’m going upstairs,” Hannah called out, retreating as usual. “Where am I sleeping, Aunt Rose?”

“I put your parents in the guest room, so you can either sleep on the sofa bed in the library or in Merry’s room.”

“I’ll take the sofa bed.”

“I thought you might. You’ll find linen and blankets all ready for you.”

“You put me in the guest room?” Birdie asked, her brows raised in obvious pique.

Rose’s toes curled, but she nodded firmly and looked Birdie in the eyes. “Yes. I put Jilly in her old room.” Then to Dennis, “I’ll get your beer.”

Birdie’s lips pursed in annoyance, but she didn’t reply. She tucked her hands in her slacks’ pockets and followed Rose into the kitchen. It was an immense room, old-fashioned, with the same white cabinets and appliances that were there when their mother cooked in the room. Only in the pantry did a large new refrigerator hum. Rose headed straight for it.

“Have you heard from Jilly yet?” Birdie asked.

“No. It’s a good thing you didn’t go to the airport,” Rose replied, pulling ice from the freezer. “You were right, as usual. The news reported delays galore and they might even shut down the airport.”

“I hadn’t heard that. But I’m not surprised. It’s really getting nasty out there.”

“I know and I’m worried. I’ve called the airline a million times but they can’t tell me anything other than that her flight is in a holding pattern. They think it will be allowed to land, which is a relief.” She yanked the cork from the bottle of cabernet she’d chosen while Birdie hunted in the cabinet for a few glasses. “We’re lucky. I gather other flights are being redirected. That would’ve been a disaster. She’d be late for the funeral.”

“Jilly does love to make an exciting entrance….”

Rose filled a glass with wine while her lips curved in a teasing smile. “That’s not fair.”

“I know, I know. I didn’t mean it.” Birdie took a long swallow of her wine. Over the glass her eyes glistened with humor. “Much. Can’t you just imagine her in that plane? She must be beside herself. You know how she hates being trapped. Remember how she was on a Chicago bus in rush hour?”

Rose shared her first laugh in days, remembering. Jilly would leap to her feet, yank the buzzer and demand to be let off the bus. Then she’d march off in a huff, her flame-red hair like ribbons of fire fluttering behind. Birdie and Rose would track her through the bus window till a break came in traffic, then they’d point and laugh at her as they sped past her. But she never looked their way. She kept her glance stubbornly straight ahead.

“Pity the poor stewardess,” Birdie said, rolling her eyes. “But I have to admit, circling up there in a confined space for hours is hell. She’ll be exhausted and cranky when she gets here. I shouldn’t be talking. It was a real push getting out of town by car and I was a total bitch, I admit it. I thought I’d kill my daughter before we arrived here.” She swirled the wine in her glass. “Be forewarned. Hannah is in one of her moods.”

“Poor baby,” replied Rose with sympathy. “She looks unhappy.”

“She is,” she replied, then added flippantly, “perpetually.”

“Is she okay?”

“Oh, yes, she’s fine.” Birdie cut off further inquiry. She didn’t like anyone to think there was any problem with her family.

“This is probably the first death she’s really experiencing. She was so young when Mom died.”

“That’s true. She’s seemed so remote, but I hadn’t thought of it that way.” She rubbed her temple and said in a low voice, “To be honest, I can’t accept it, either. It’s so hard. I keep going over it in my mind, how quickly she went downhill. If only I could have been here…”

“No, Birdie,” Rose said firmly. “Don’t go there. It isn’t healthy. Her doctor was here with her. Really, there was nothing you could have done.”

“You don’t know that!”

Rose grabbed her hand to still it and looked directly into her sister’s eyes. “I know what you’re thinking,” she said in her quiet voice that could be surprisingly firm. “That you could have saved her.”

Rose had nailed it. Birdie squirmed in discomfort and tried to snatch back her hand, but Rose held on tight.

“You couldn’t have done anything to save her, Birdie. Not this time.”

Birdie stared into her hazel eyes, blazing with intent, until the message slowly, reluctantly sunk in. When she indicated her understanding, if not acceptance, with a nod, Rose released her hand then smiled faintly and looked away, a little embarrassed about the intense exchange. Birdie took a long, deep breath and said in a robust manner, “So now we’re planning her funeral.”

“Yes.”

“Yes.” Birdie paused. “I’m sorry you got dumped with checking all the funeral details. I tried to get here early today but the traffic was unbelievable and…”

“Don’t be silly. I needed something to do.”

“I have to tell you, I’m concerned about the luncheon at Alfredo’s. I telephoned them before I left Milwaukee just to check on our reservation and see if there was anything else that needed taking care of. The idiot girl I spoke to said we didn’t have one! Can you believe that? I didn’t have time to talk to the manager, but I told her to look into it and I’d follow up when I got here. She probably just got something mixed up in her book but I worried the whole way down. Do you have the number handy? I’ll give them a quick call. If they’ve screwed up…”

“Birdie,” Rose said hesitatingly. She plucked at the loose threads of the oven mitt, then took a deep breath. She hadn’t meant to get into this before Birdie had a chance to relax, maybe had a second glass of wine. “They didn’t screw up. I…I never made the reservation.”

Birdie’s eyes widened with disbelief. “What?”

“Don’t worry, I’ve taken care of everything,” Rose rushed to say.

“What do you mean you didn’t make the reservation? Why? We discussed this in detail. My God, Rose, what were you thinking? Did you forget? Why didn’t you tell me? Damn, I don’t know if we can reserve a room for tomorrow on such short notice.” Her voice was high and she placed her hand to her forehead as she paced across the linoleum.

“I didn’t tell you because I knew you’d react like this. You’d drive in from Milwaukee and take over like you always do.” At the surprise on Birdie’s face she softened her tone. “I wanted to do something special for Merry. For all of us—you, Jilly and me. We hardly know one another anymore, Birdie. We need to remember Merry and the good times we had together. I didn’t think we could do that in a restaurant.”

Birdie spread out her palms in a futile gesture. “We can spend all the time we want together, just the three of us. Here at home. But we still could have had the funeral lunch at a restaurant. Oh, Rose, what have you done? It would have been so much easier.”

“For whom?” she replied sharply, nettled by the allknowing tone in Birdie’s voice. “I want to do this. And it’s really not so difficult. I’ve planned for a light lunch here in this wonderful home where we all grew up. It’s much more personal, and with all the flowers already here, it will be beautiful. It just didn’t seem right to have the funeral lunch for Merry at a restaurant that she’d never even been to.”

“Oh, come on, Rose, this has nothing to do with Merry,” Birdie fired out. “You’re the one who wants it here. It’s you who can’t stand the idea of leaving the house.”

Rose sucked in her breath, stung by the truth in the comment. She clasped her hands tightly in front of her. “That’s only partly true,” she replied, looking away. “Just because I don’t like leaving the house doesn’t mean I can’t. I truly believe Merry would want it here, too.” Rose raised her eyes and held her sister’s gaze. “And I know—better than you or anyone else—what Merry would want.”

Birdie had the grace to concede. “No one could ever dispute that.”

The tension eased a bit between them and Rose spoke from the heart. “Merry and I used to dream all the time about having parties. But we never did. It’s kind of sad when I think of that. The last time this house saw a party was your wedding and that was…what? Twenty years ago? Mom has so many pretty things crammed into boxes that no one ever uses. Platters and urns, punch bowls and coffee urns, china and silver. You wouldn’t believe half of what’s stored in these chests and cabinets.” She stepped closer, eager to assure Birdie that all would be well. “What are we saving it for? Let’s use it, all of it! I only wish I’d done something special for Merry while she was alive.”

Birdie frowned, but it was more with worry. “It’s a lot of work.”

“It’s all under control. I’ve ordered sandwich meat and all sorts of things from the deli and two cakes from Mueller’s bakery. Custard cream and angel food, Merry’s favorites. And cookies, too, chocolate chip and four-pounds-of-butter ones. We’ll have hot coffee and tea with fresh cream. Really, Birdie, it will be lovely.”

“You could have told me.”

Rose took heart at the tone of resignation. “I know, I know. I’m sorry.”

Hannah burst into the kitchen, coming to a halt as her eyes shifted back and forth between her mother and her aunt. “Is everything okay in here? Should I leave?”

“Yes, everything is okay and no, of course you shouldn’t leave,” Rose replied easily. She looked at Birdie and smiled. “We’re just having a disagreement about the plans for tomorrow.”

“Watch out, Aunt Rose. Mom is in one of her moods.”

Rose’s lips twitched at the echo to Birdie’s earlier comment about Hannah. She was pleased to see Birdie’s lips curve into a smile as well.

“Like mother like daughter,” Birdie said, surprising Hannah by wrapping an arm around her shoulder and giving her a squeeze. Hannah wriggled out of the embrace and reached for a cracker to nibble. Birdie grabbed a cracker, too, and after a bite she said in an offhand manner, “The church service is still on, at least? I had to duke it out with Hannah to wear her black dress. I’d like to think the bruises were worth it.” She winked at Hannah.

“Very funny.” Hannah rolled her eyes.

“Father Frank is saying mass and Kathleen Murdoch is all set to sing,” Rose said. “She has such a lovely voice.” She poured the crackers onto a plate. “Merry loved to listen to her on Sundays.”

“Good. And everything is as I arranged it at the funeral parlor?”

Rose hesitated, seemingly busy arranging the crackers. Birdie leaned forward so her face was close to hers. “Please, Rose, tell me. What did you do now?”

“Nothing major. It’s all taken care of.”

“What?”

Rose raised her head, flinching at the pair of eyes trained on her. There was nothing left for her to do now but jump right in. “I ordered a different casket, okay? I saved a great deal of money by shopping on the Internet.”

Hannah’s hand stopped midair en route to delivering a cracker to her mouth. “You shopped on the Internet…for a casket?”

Birdie looked stunned. “You’ve got to be kidding.” When Rose didn’t respond Birdie’s eyes widened further. “You’re killing me, Rose. I spent hours on this! I had everything ordered at Krause’s Funeral Home. Why did you have to change it?”

“Birdie, I don’t know why you’re so upset just because everything is not exactly the way you ordered it.” Rose’s voice was clipped. “You never once asked me what I wanted to do for the funeral. You just called up and told me what to do. I went along with it, as I usually do. But for heaven’s sake, this isn’t a change as much as, well, a better deal.”

Birdie put her face in her palms. “Please tell me there’s a casket for my sister tomorrow.”

“Of course there is. You ordered an oak casket, and though it was lovely, it cost two thousand dollars. I found one almost identical for nine hundred dollars.” Her pride couldn’t be disguised.

“Mom,” Hannah said in that teenage know-it-all voice, “you can buy anything on the Internet these days.”

Rose shrugged. “I’m on the computer a lot for my word processing job. When I need a break I surf the Net. It’s fun, relaxing. In fact, it’s how I keep in touch with the world out there. I find it absolutely fascinating. When I’m on the Net, I feel so connected.”

Hannah waggled her brows. “Are you doing those chat rooms?”

Rose didn’t answer, but she could feel the blood rushing to her cheeks.

“Oh, no,” Birdie groaned. “You are, aren’t you.”

“What if I am?” Rose laughed lightly but her color heightened.

“You do know there are a lot of creeps out there that prey on lonely women like yourself.”

“They’re not all creeps. There are some very nice people looking for someone to talk to.”

Birdie released a short, sarcastic laugh.

“Lots of people are in chat rooms,” Hannah said in Rose’s defense.

“Not you, too, I hope,” Birdie replied with narrowed eyes.

“Sure I am.”

Birdie leaned back against the counter. “Good God, is there anything else I don’t know? My sister and my child are hanging out in chat rooms, we’ve got some casket coming in the mail and, as far as I’m concerned, we’re having a damn picnic in the house tomorrow.”

Dennis stuck his head around the corner. “Hey, in case you’re interested, there’s a chauffeur at the door.”

3

BIRDIE AND ROSE LOOKED AT each other for a brief instant, then in a flash, Rose darted from the table and tore off to open the front door as eager as a nine-year-old girl. A tall, blond man with a bodybuilder’s physique squeezed into a black suit smiled uncertainly.

“Excuse me, ma’am, but is this the Season residence?”

Rose looked beyond the man’s massive shoulders into the darkness but didn’t see her sister. Only the sleek red lights that trimmed the limo were visible along the curb. A shiver of worry shot through her as she nodded.

The chauffeur pinched back a smile and said, “My passenger told me to tell you to meet her in the side yard.”

Rose wasn’t sure she’d heard right. Behind her, Birdie stepped forward to ask in her imperious voice, “Where is Miss Season?”

The chauffeur cleared his throat and leaned forward in a confidential manner. “In the side yard. She should really come inside. She’s…well, she’s had a bit too much to drink.”

Rose heard Birdie mutter an oath. Dennis stepped forward and shook the chauffeur’s hand in a man-to-man manner. “Why don’t you bring her luggage right inside.” He looked over his shoulder, jerking his head at Birdie.

“Come on, Rose, let’s go get her,” Birdie said. They hurried into their coats and out the door into the night. Hannah was right behind them.

The snow had finally stopped and the full moon was as white as a large plate in the inky black sky. The light illuminated the clean, virginal snow in breathtaking beauty. Rose had always felt a particular thrill stepping into a stretch of new snow, akin to being an explorer discovering uncharted territory. Ahead, the path of her sisters’ deep footprints in the nearly foot-deep snow were the only marks scarring the frosty white. She followed them, trying to step in their prints, with a curious excitement in her chest. Around the wide front porch she could hear high-pitched laughing and shrieking.

Turning the corner, she saw in the moonlight a flash of vivid red hair and lush black mink against a sea of white. Blinking in the cold air, she moved closer. Birdie was standing a few feet away from the blur of motion, her hands on her hips. Rose saw Jillian lying in the snow, laughing with delight, as her mink-clad arms and her long, slender legs in dainty spiked heels moved back and forth, carving out a snow angel.

“Jilly!” Rose cried out with joy.

Jilly stopped laughing, cocked her head up and waved her arm, beckoning Rose closer.

“Rosie!” she shouted. “Look at all this snow! Isn’t it beautiful? I haven’t seen snow like this since we were kids. It’s so damn wonderful. Come on, Rosie! Birdie! Remember how we used to make snow angels? Look, I’ve made two already!”

Sure enough, Rose spied two snow angel outlines looking somewhat ethereal and magical in the moonlight. Rose ran to Jilly’s side, bubbling with anticipation. Except, she couldn’t remember how to make the angel. Suddenly Hannah appeared beside her, grinning with delight.

“So cool,” she exclaimed joyously. Spreading her arms out, she simply fell back into the soft snow, then began to thrash her arms up and down in an arc.

“Hannah, get out of there!” Birdie called, exasperated. “Oh, no, Rose, don’t you dare. Rose!”

With a squeal, Rose shut her eyes, spread out her arms and fell back. It was deliriously delicious, like free-falling, then finding herself deeply enveloped in the snow, face up to the moonlight.

“Aw, come on, Birdie, you ol’ stick in the mud,” Jilly called out. “Nobody’s looking.”

Birdie stood a few feet away, feeling every inch of the distance.

“Jilly, you’ll catch your death of cold,” she scolded. “You all will. No boots, no gloves, no hats. You’re all behaving like children. Jilly, come on, give me your hand.”

Jilly lifted her hand as gracefully as a queen’s. When Birdie stepped forward to take it, Jilly whipped up her other hand, clasped Birdie’s tightly and pulled her down with a laugh. Birdie shouted in surprise and tumbled face first into the snow beside her sister.

The snow was icy on her cheeks but nothing was hurt, except maybe her pride. The sound of hilarious laughter filled her ears. Birdie sputtered and felt ready to throttle her older sister, who was obviously drunk. She could smell the Scotch mixed with perfume. She struggled to raise herself to her knees and wipe the snow off her cheeks, scowling, ready to light into her sister.

But then she saw Jilly’s face, inches from her own, lit up with laughter. Birdie could only stare into that beautiful face, beautiful not for the reasons fashion magazines had clamored for her picture, but because it was the face she remembered from their childhood. Jilly’s eyes were bright with a childlike joy and that incomparable pleasure of just being alive that she hadn’t seen in her since they were kids. Birdie wasn’t sure if Jilly was happy, or merely drunk.

“Missed you, sis,” Jilly said soberly, still looking into her eyes with a wistfulness that was endearing. She reached up to swipe away a chunk of snow from Birdie’s collar. “You always made the best snow angels, remember? The snow was just like this, too. Soft, like powder. Remember?” Then with a cocky smirk she added, “But I always had to drag you out here, even then.”

Though the words were slurred, Birdie smiled and nodded, remembering it all.

Hannah sat up and howled with laughter at seeing her mother dumped in the snow. There was a look of awe on her face; she couldn’t believe anyone would really dare to do that to her mother. Beside her, Rose, the traitor, was laughing so hard tears were icing on her lashes and she clapped her hands in the same spontaneous manner she used to when she was little.

Something deep within Birdie pinged; she could hear the sound in her mind as clearly as she heard the laughing of the three women she loved most in the world. It was a rare moment of intense beauty and joy. Their world, their senses, felt heightened. She breathed in the cool air, slowly and deeply, feeling the moisture slide down her throat and enter her lungs. The snow made her cheeks burn with cold. She imagined they were cherry red, like Hannah’s, and the sting made her feel alive.

What small miracle had transpired that allowed her to be kneeling in the new-fallen snow in the moonlight with her sisters, laughing like children. Playing, rather than fussing over details of the funeral?

She knew the answer, of course. Jilly. It had always been Jilly who started the games.

Ah, but it was cold, and late, her mind rushed to warn her. They couldn’t stay out here forever. Reality interfered. Suddenly, she was no longer a child but a grown-up, with an adult’s sensibilities. She knew that a drunk could get hypothermia and not even know it. She knew that there were countless details to be sorted out before the funeral tomorrow. The dinner had to be served. Jilly probably needed to get some food in her. And unlike her sisters, Birdie was a mother. A wife. A doctor. She had responsibilities.

In a flash, she felt herself projected out from the scene, becoming an outsider, looking in. She couldn’t play. She pushed a hand through her hair and looked again at Jilly, then at Rose, and finally her own daughter, Hannah, still making snow angels. Birdie felt very cold. Her fingertips were flaming red and her toes were numb. “Okay, everybody, time to go in.”

“Okay, Mom,” Rose called back, giggling at her own joke.

Birdie wanted to shout back that she wasn’t her mother. She didn’t want to be the mother. Slowly, she dragged herself to her feet, feeling every one of her forty-one years.

“I said, everybody up. Time to go in.”

Ever the cooperative one, Rose climbed to her feet and offered her hand to Jilly. This time, Jilly went along, allowing Rose to take one hand and Hannah the other as they hauled her to her feet. She rose like a beautifully plumed bird, graceful, arms outstretched. A phoenix, Birdie thought with a wry smile.

“I think I’m going to be sick,” Jilly moaned once she was on her feet, weaving.

“Too much booze,” Birdie said matter-of-factly as she stepped forward to grab hold of Jilly’s arm. “Can you walk?”

“I’m a model, chérie. I’ve strolled down runways in a lot worse condition than this.”

“Spare me the details. Okay then, one foot after another.”

Like a trooper, Jilly straightened her shoulders, fixed her direction. Then, releasing her sister’s hand, she paced through the snow with remarkable grace.

“You didn’t tell me your sister was so cool,” Hannah said, coming to her side.

Birdie saw the admiration in Hannah’s eyes and felt a sting of jealousy. She couldn’t remember the last time she had seen anything but scorn in her daughter’s eyes.

A squeal caught her attention. She looked up in time to see Jilly wobble on some ice in the ridiculous spiked heels, then fall flat back into a snowdrift. Birdie hated herself for it, but a part of her was glad to see Jilly knocked off the pedestal a notch. She stifled her smile and hurried to help Jilly to her feet with Rose catching the slack. Jilly seemed to have used the last of her steam to make the distance to the porch; she was like a rag doll now.

In the light of the front porch, Birdie studied her sister with a physician’s eye. It had been ten years since she’d last seen her. Jilly still possessed a sultry sexiness that even women turned their heads to admire. Her hair was the color of flame and as thick and wild as ever. She wore much less makeup now so her face appeared more pleasing and natural. But Birdie didn’t like its pallor and gauntness, nor the puffy eyelids and the blueness of her lips. And Jilly was thinner. The bones of her face and even her hands appeared sharp under blue-veined skin. Intuition bred from years of training and experience recognized excessive fatigue and possible illness.

“Help me get her up, Rose,” she murmured.

Rose and Hannah both responded to the serious tone in Birdie’s request. The sisters each shouldered part of Jilly’s weight while Hannah opened the front door.

“I’m okay….” Jilly muttered.

“Sure you are. Now, take another step. Up, up, up,” and so on as they made their way up the front steps.

“Welcome home, Jilly,” Rose murmured as they ushered her into the warmth of their old family house.

Hours later, the dishes were washed and put away, the lights turned off and everyone settled into their respective rooms. The whole house seemed to sigh in peace. Rose sat before her computer, wide-awake. Coffee had been served when they all came in from the cold. Though she didn’t usually drink caffeine at night, that wasn’t what stirred her blood. There had been too much emotion and tomorrow promised more.

These dark hours were her favorite, when no one needed her or called her name. They were hers alone. Merry had always fallen asleep quickly and early and slept untroubled through the night. Occasionally illness would rouse her, but usually her breath purred and she dreamed of happy things. Rose knew this because she’d sit by her bed and watch her, envious of the gentle smile that curved Merry’s lips.

Her bedroom had once been their parents’ room. Rose had offered this largest bedroom to Merry after their mother died but Merry had rejected it, preferring the familiarity of her own lavender-and-lace-filled room. So Rose had moved in, using her old room as an office for her part-time job as a word processor. There were twelve rooms in the house, but her office was hers alone, filled with things that she had chosen for herself rather than inherited. Her desk was designed for her new computer. The bookshelves were installed to house her personal library. Everything here was here only because she wished it to be. She could come into this room, close the door and be free to explore her own interests, either through books or, more recently, the Internet.

She turned on the computer and, as she waited for it to boot, thought that Birdie was wrong to say chat rooms were only for lonely shut-ins. She knew this wasn’t true because her Internet friend, DannyBoy, traveled all across the country as a trucker. They didn’t go into personal details, didn’t exchange pictures or such, but she gleaned from what he wrote that being on the road so much was the reason he couldn’t meet nice young ladies. He wasn’t some pervert. He was kind and caring. A real gentleman who never was vulgar, or stupid, or chauvinistic. In fact, he was the nicest man she’d ever met, if only in cyberspace. They’d met months ago in a chat room for stamp collectors, and their conversations had soon drifted from stamps to whatever was on their minds. They’d liked what each other had to say and she wasn’t surprised when he e-mailed her privately.

As she clicked to her mail, she felt the familiar thrill to see his e-mail waiting for her. DannyBoy had been her greatest ally when she’d decided to buck Birdie’s directives and have her luncheon. He’d been the one to write words of condolences, sincere and heartfelt. Though she’d never seen his face, Rose could honestly believe DannyBoy was her best friend. She clicked open the e-mail.

Dear Rosebud,

All day I kept thinking and wondering if your sisters had come yet. I know how excited you are and how sad that the occasion for this get-together is your youngest sister’s funeral. I heard on the weather report about all that snow you folks in Chicago got. What bad luck. Hope it all goes okay. Let me know.

I’m in Texas now. The weather is pretty good, but the clouds are collecting and in these parts, we all keep our eyes on the sky and our ears tuned to the radio. Moving on soon, though, to the Midwest.

DannyBoy

She smiled, wondering as she always did what he looked like, how old he was, and if he was tall or short, fat or thin, balding or wore his hair in a ponytail. Not that it mattered, of course, though she couldn’t help but be curious. She put her fingers to the keyboard.

Dear DannyBoy,

Yes, they’re here! We had a terrible snowstorm but we’re lucky. Birdie and her family made it down and Jilly’s plane got in, though late. It’s so very wonderful! I really should go to sleep. Tomorrow is a busy day. I’ve a million things to do. I’ll have to get up early and polish the silver, set the tables, make the sandwiches. Oh Lord, the list never ends. But I can’t sleep. My blood feels like it’s racing yet my eyelids are so heavy. I haven’t slept well lately. I hate the darkness. I lie in bed staring at the ceiling until I see red spots before my eyes. I don’t know what I’m waiting for, but I have this sense something is going to happen. Maybe Merry is hovering nearby. Who knows? I hope I don’t sound crazy. I probably just need some sleep. But my sisters are here!

Take care,

Rosebud

She sent the letter. While she was scanning the Net, she was surprised to see another letter come in. Clicking over, she saw it was from DannyBoy. He must be online, she thought, feeling a sudden, almost intimate connection with him.

Dear Rosebud,

Go to sleep!

DannyBoy

4

JILLY AWOKE TO A PERSISTENT STRIPE of bright light seeping in from behind the curtains. It spread across the room playing with the shadows. She lay flat on her back, disoriented, drymouthed, in that limbo space between wakefulness and deep sleep. She was aware only of being very cold, and not knowing where she was. Blinking, she thought the bed was different. The walls…the smells.

Then suddenly in a rush, she knew.

She was in her old room, the one she’d shared with Birdie so many years before. She blinked again, then wiped her face with her palms. Her brain was awake now, absolutely, but her body wasn’t. Perhaps it was the jet lag, perhaps just the excitement of being home again after all these years, but she knew there would be no closing her eyes and falling back asleep. And for that, there’d be hell to pay. She’d had too much to drink last night. Her head was already pounding with a hangover and lack of sufficient sleep. A bad combination, and one all too familiar.

She licked her dry lips and dragged herself up to her elbows to take stock. She was wearing only a bra and undies. Rose and Birdie must have helped her out of her clothes. If she were in her own apartment in Paris she’d get up, boost the heat a bit, slip thick socks on her feet, then search around the kitchen for something to eat and perhaps something hot to drink. Maybe even listen to some music. But she didn’t want to wake anyone up, especially not Merry.

Jilly rubbed her eyes, waking further. No, she thought with a pang, she couldn’t wake Merry.

She dragged herself to a sitting position and took stock of the room. Nothing had changed. Her square white dresser was still covered with her collection of miniature boxes, each undoubtedly filled with the same costume earrings, buttons, pins and rings she’d carelessly tossed in eons ago. Birdie’s was topped with swimming trophies and medals attached to blue ribbons. There were two twin beds with matching swirling white wrought-iron headboards. On Birdie’s bed lay her favorite teddy bear, a big white one that was now as dirty and gray as the morning light. She looked down by her feet then cracked a smile, feeling more delight than she thought she would on finding her own teddy bear still there. It was a ratty, old-fashioned brown bear with stuffing sticking out from the roughly repaired seams.

“Hello, Mr. President,” she said, reaching out to pull the bear close, oddly comforted by it.

It was so eerie to see everything as she’d left it years ago. She hadn’t expected it to be the same. Rather, she’d thought all traces of the big bad sister would have been weeded out. It felt nice to see some trace of the young Jillian Season still remained. Rose was a sweetheart for putting her back in her old room. Oh, the dreams she’d had sleeping in this bed!

And the nightmares.

The last time she’d slept in here was in her senior year of high school, before she left for Marian House. When she’d returned, her mother had moved her to the guest room. It was all part of her mother’s infinite plan. Marian House was never to be discussed. Not even with—especially not with—her sisters. Her mother had arranged for Jilly to leave for a year’s study at the Sorbonne immediately after graduation. After all, she had painstakingly explained to Jilly, by going so far away, she wouldn’t have to deal with all those prying questions about where she’d been the previous months.