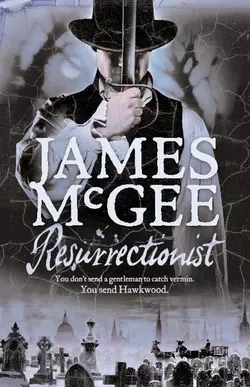

Resurrectionist

James McGee

Hawkwood, the Regency James Bond, returns in this gripping, action packed sequel to the bestselling ‘Ratcatcher’.Matthew Hawkwood. Soldier, spy, lover – a man as dangerous as the criminals he hunts.The tough Bow Street Runner is back where he's not wanted, in the most forbidding places London has to offer: its graveyards and the rank, sinister halls of Bedlam, the country’s most notorious lunatic asylum.There are missing bodies all around – dead and alive. 'Resurrection men' serve the demands of the city's surgeons by stealing corpses – and creating a few of their own along the way.Far more worrying is the escape from Bedlam of a very unusual inmate: one Colonel Titus Xavier Hyde, an obsessive, gifted surgeon whose insanity is only matched by his dark intelligence. And this twisted genius has a point to prove. Which will mean plenty more work for the gravediggers…

JAMES McGEE

Resurrectionist

CONTENTS

Cover (#u4775e87f-636d-5072-bee2-bcd5eed87152)

Title Page (#u59d50f74-4cbf-5a3b-aa31-a4442ddf9a87)

Prologue (#u18fd368c-dea6-592f-88e2-121c37c4c8a8)

1 (#u89be1729-e7fd-5d1f-b106-f2bead6e2d96)

2 (#u9ca7aff5-928b-59a0-825e-9016b256ebf4)

3 (#u4ec5c12d-687d-574b-80bc-b2f1ff27c909)

4 (#u8bd8ac68-c6a2-5763-9830-51e44a5c01c4)

5 (#ub133e03b-0034-5fc6-abce-79cdebf30edc)

6 (#u3203171d-c495-5578-b2bc-48fbf5d6e1dd)

7 (#litres_trial_promo)

8 (#litres_trial_promo)

9 (#litres_trial_promo)

10 (#litres_trial_promo)

11 (#litres_trial_promo)

12 (#litres_trial_promo)

13 (#litres_trial_promo)

14 (#litres_trial_promo)

15 (#litres_trial_promo)

16 (#litres_trial_promo)

17 (#litres_trial_promo)

18 (#litres_trial_promo)

19 (#litres_trial_promo)

20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Historical Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE (#ulink_219f8086-8770-5dc1-9993-2cf3e00d89cc)

When he heard the sobbing, Attendant Mordecai Leech’s first thought was that it was probably the wind trying to burrow its way under the eaves. On a night such as this, with rain lashing the windows like grapeshot, it was not an unusual occurrence; the vast building was old and draughty and had been condemned years ago. Only as Leech turned the corner at the foot of the broad stairway leading to the first floor, candle held aloft, did he realize that the weeping was not emanating from outside the building but from one of the galleries on the landing above him.

The galleries were long with high, arched ceilings and sound had a tendency to travel, so it was hard to tell the exact source of the distress, or even whether the sufferer was male or female.

Probably the bloody American, Norris, Leech thought, as another low moan drifted down the stairwell. It was followed by a long-drawn-out howl, like that made by a small dog. Judging from the intensity of the ululation, it sounded as if the poor bastard was in mortal torment, in the throes of another of his regular nightmares. But then, Leech reflected in a rare moment of compassion, if I were chained to the bloody wall by my neck and ankles, I’d probably be suffering bad dreams too.

The howl gave way to a keening wail and Leech cursed under his breath. The ruckus was liable to disturb the wing’s other inhabitants, and once they’d picked up the din and joined in it would sound like feeding time at the Tower menagerie, which was a guarantee that no one would get a wink of sleep. God rot the mad bastard!

Reluctantly, Leech prepared to mount the stairs, only to be startled by the harsh jangle of a bell. Suddenly he remembered that was why he’d come downstairs in the first place – in answer to a summons from someone outside, requesting admittance. Leech reached into his jacket pocket and consulted his watch. It was a little after ten o’clock. He didn’t need to look through the inspection hatch to see who it was.

As he was reaching for the bolts on the inside of the door, Leech noticed that the wailing had stopped. It was as if the sound of the bell had triggered the silence. He breathed a sigh of relief. Maybe it would be a quiet night after all.

The door swung inwards to reveal a slender figure dressed in a black, rain-sodden cloak and wide-brimmed hat, dripping with water. A woollen scarf, wrapped round the visitor’s neck and lower face as a protection against the inclement weather, hid his features.

Leech stood aside to let the man enter. “Ev’ning, Reverend,” he whispered. “I was wondering if the bloody rain would keep you away. Beggin’ your pardon,” Leech added hurriedly. His voice remained low, as if he was afraid he might be overheard. Members of the clergy were not welcome here. That was the rule, by order of the governors.

The clergyman untied his scarf, revealing his clerical collar, and lifted his head. “I was detained; a burial service for one of my parishioners and a host of other duties, I’m afraid.”

In raising his head and thus elevating the brim of his hat, the clergyman’s countenance was revealed. It was neither a young nor an old face. But there was wisdom there, in the eyes and the crow’s feet and the deep furrows etched into the cheeks and forehead. There were several scars, too, along the jawline: small and round, hinting at a brush with some variation of the pox. High along the priest’s right cheekbone what looked suspiciously like a wound from a blade had created a shallow runnel.

Leech had often wondered about the scar and the priest’s background, but he had been too wary to ask the man directly and no one he had mentioned it to knew the circumstances of the disfigurement; or, if they did know, they chose not to impart information on the subject. So Leech remained ignorant and more than a mite curious.

The priest removed his hat and cloak and shook them to expel the rain. “How is he?”

Leech shrugged. “Wouldn’t know, Reverend. I don’t have a lot to do with ’im. You probably see more of ’im than I do. I make sure ’is door’s bolted and that he gets ’is victuals, an’ that’s as much as I ’as to do with it. An’ that suits me just fine. Anything else, you’d be better askin’ the apothecary. How long’s it been since you’ve seen ’im?”

“We played our last game a week ago. I was soundly beaten, I’m afraid. His command of strategy is quite formidable and, alas, I was rather a poor adversary. However, he was exceedingly magnanimous in victory.” The priest patted Leech’s arm. “Let us hope this evening’s contest proves more rewarding.”

Another low moan drifted down from on high and the keeper tensed. “Buggeration. Er … sorry, Reverend.”

The slam of a metal door from deeper inside the building echoed through the darkened wing. It was followed by the sound of heavy footsteps and an angry warning. “God damn it, Norris! If you don’t keep it down, I’ll be in there tightening the bloody screws!”

As if at a given signal, the threat was answered by an uneven chorus of raised voices in varying degrees of excitement. This was followed, in quick succession, by a cacophony of high-pitched screams, a peal of hysterical laughter and, somewhat incongruously, what sounded like the opening chant of some religious exultation.

“Hell’s bleedin’ bells!” Leech spat. “That’s gone and done it.”

The priest shook his head. “Poor demented souls.”

Poor souls, my arse, Leech muttered under his breath. Aloud, he said, “Come on, Reverend, I’ll take you to him. Quickly now, stay close to me. And I’d be obliged if you’d put your ’at back on and keep your scarf high. Don’t want any pryin’ eyes spottin’ your collar. Wouldn’t want either of us to get into trouble.” The attendant jerked a thumb skywards. “Then I can go and help deal with that lot upstairs.”

Casting a wary eye around him, Leech turned and led the way along the dimly lit corridor. The priest hurried in his wake. Gradually, the noise from the first floor began to recede as they left the stairs behind them.

Not for the first time, the priest was struck by the speed at which decay was spreading through the building. There were wide cracks along the edges of the ceiling. Rainwater was running down the walls in streams. Many of the window frames were so far out of alignment it was clear that some sections of the roof were too heavy for the bowed walls to support. The entire edifice was crumbling into the ground.

Leech turned the corner. Ahead of them a long corridor led off into stygian darkness. A blast of rain splattered loudly against a nearby window. The sound was accompanied by a groan like that of an animal in pain.

Leech grinned at the priest’s startled expression. “Don’t worry, Reverend, it’s only the rafters. Used to be in the navy,” the attendant added, “I knows a bit about ship building. Got to give the ribs room to breathe. Same with this place. Mind you, the stupid buggers only went and built her on top of the city ditch, didn’t they? Know what we’re standing on? About six inches o’ rubble. Below that there’s naught but bleedin’ soil. We ain’t just leakin’, we’re bloody sinkin’ as well!” Leech looked up. “Anyways, we’re here.”

They were standing in front of a solid wooden door. Set into the door at eye level was a small, six-inch-square grille, similar to the screen in a confessional. At the base of the door there was a gap, just wide enough to admit a food tray. Both the grille and the gap were silhouetted by the pale yellow glow of candlelight emanating from inside the room.

Leech reached for the key ring at his waist.

“You know what to do, Reverend. Pull on the bell as usual. It’ll ring in the keepers’ room. I’ll be off at midnight, unless the buggers upstairs are still awake, but old Grubb’ll be on duty. He’ll be waitin’ to unlock the door and see you out.”

The priest nodded.

Leech gave the door a wary eye. “You’ll be all right?”

The priest smiled. “I’ll be perfectly safe, Mr Leech, but thank you for your concern.”

Leech rapped the key ring on the door and placed his mouth against the metal grille. “Visitor for you. The Reverend’s here.”

Leech waited.

“You may enter.” The voice was male. The soft-spoken words were measured and precise. There was something vaguely seductive in the tone of the invitation that caused the short hairs on the back of Mordecai Leech’s neck to prickle uncomfortably. Slightly unnerved by the sensation, though he wasn’t sure why, the keeper unlocked the door, pushed it open, and stepped back.

In the corner of the room, a shadowy figure rose and moved slowly towards the light.

The priest stepped over the threshold. Leech closed and locked the door, then waited, head cocked, listening.

“Good evening, Colonel.” The priest’s voice. “How are you this evening?”

The reply, when it came, was low and indistinct. Leech tipped his ear closer to the door but the conversation was already fading as the occupants moved away into the room.

Leech stood listening for several seconds then, realizing that it was pointless, he turned on his heel and made his way back down the corridor. As he approached the stairwell his ears picked up the sounds of discordant singing and he groaned. Sounded as if they were still at it. It was going to be a long night.

Half an hour after midnight, the bell rang in the keepers’ room. Amos Grubb sighed, wrapped the blanket around his bony shoulders, and reached for the candle-holder. Attendant Leech had warned him to expect the summons. Even so, Grubb felt a stab of resentment that he should have to vacate his lumpy mattress in order to answer the call. The wing was quieter now, after the recent disturbance. It was quite astonishing the effect a bit of laudanum could have on even the most obstinate individual. One small drop in a beaker of milk and Norris was sleeping like a baby. Most of the others, nerves soothed by the resulting calm, had swiftly followed suit. A few were still awake, snuffling and whispering either among or to themselves, but it was relatively peaceful, all things considered. Even the rain had eased, though the wind was still whistling through the gaps around the window frames.

It was bitterly cold. Grubb shivered. He’d been hoping to get his head down for a few hours before making his early-morning rounds. Still, once the visitor was on his way, Grubb thought wistfully, he could look forward to his forty winks with a clear conscience.

The elderly attendant swore softly as he squelched his way along the passage.

He halted outside the locked door and rattled the keys against the grille.

There was the sound of a chair sliding back and the murmur of voices from within.

Grubb unlocked the door and stepped away, holding his candle aloft. “Ready when you are, Reverend.”

Grubb saw that the priest was already wearing his cloak. He’d donned his hat and scarf, too. The clergyman turned on the threshold. “Goodbye, Colonel, my thanks for a most convivial evening. And very well played, though I promise I’ll give you a good run next time,” he said, wagging an admonishing finger.

Stepping through the door, the priest drew himself tightly into his cloak and waited as Grubb secured the door behind him.

Together, they set off down the passage. Grubb led the way, candle held at waist height, on the hunt for puddles. He was conscious of the priest padding along at his side and glanced over his shoulder, trying to steal a look at the clergyman’s face. Leech had asked him about the scars a month or two back. Grubb had confessed his ignorance and was as curious as his colleague to learn their origin. He couldn’t see much in the gloom. The priest’s head was still bowed as he concentrated on watching his footing, his face partially obscured beneath the lowered hat brim, but Grubb could just make out the scars along the edge of the jaw. The attendant’s eyes searched for the jagged weal across the priest’s right cheek. There it was. It looked different somehow, more inflamed than usual, as though suddenly suffused with blood.

As if aware that he was being studied, the priest glanced sideways and Grubb felt the breath catch in his throat. The priest’s eyes were staring directly into his. The obsidian stare made Grubb blanch and lower his gaze. The old attendant sensed the priest raise the scarf higher across his face, as if to repel further examination.

Wordlessly, Grubb led him to the front hall and waited as the clergyman adjusted his hat. Then he unlocked the door.

Across the courtyard, almost obscured beyond the veil of drizzle, Grubb could just make out the entrance columns and the high main gates.

“Can you see your way, Reverend, or would you like me to fetch a lantern?”

The priest stepped out into the night then paused, his head half turned. When he spoke, his voice was muffled. “Thank you, no. I’m sure I can find my way. No need for both of us to catch our death. Good night to you, Mr Grubb.” He set off across the courtyard, head bent.

Grubb stared after him. The priest looked like a man in a hurry, as if he couldn’t wait to leave. Not that Grubb blamed him. The place had that sort of effect on visitors, particularly those who chose to come at night.

The priest vanished into the murk and Grubb secured the door. He cocked his head and listened.

Silence.

Amos Grubb drew his blanket close and mounted the stairs in search of warmth and slumber.

It was the pot-boy, Adkins, who discovered that the food tray had not been touched. An hour had passed since it had been placed in the gap at the bottom of the door, and the two thin slices of buttered bread and the bowl of watery gruel were still there. Adkins reported the oddity to Attendant Grubb, who, shrugging himself into his blue uniform jacket, went to investigate, keys in hand.

Adkins wasn’t wrong, Grubb saw. It was unusual for food to be ignored, given the long gap between meal times.

Grubb banged his fist on the door. “Breakfast time, Colonel! And young Adkins is here to take your slops. Let’s be having you. Lively now!”

Grubb tried to recall what time the colonel’s visitor had left the previous evening. Then he remembered it hadn’t been last night, it had been early this morning. Perhaps the colonel was in his cot, exhausted from his victory at the chessboard, although that would have been unusual. The colonel was by habit an early riser.

Grubb tried again but, as before, his knocking drew no response.

Sighing, the keeper selected a key from the ring and unlocked the door.

The room was dark. The only illumination came courtesy of the thin, desultory slivers of light filtering through the gaps in the window shutters.

Grubb’s eyes moved to the low wooden-framed cot set against the far wall.

His suspicions, he saw, had been proved correct. The huddled shape under the blanket told its own story. The colonel was still abed.

All right for some, Grubb thought. He shuffled across to the window and opened the shutters. The hinges had not been oiled in a while and the rasp of the corroding brackets sounded like nails being drawn across a roof slate. The dull morning light began to permeate the room. Grubb looked out through the barred window. The sky was grey and the menacing tint indicated there would be little warmth in the day ahead.

Grubb sighed dispiritedly and turned. To his surprise the figure under the blanket, head turned to face the wall, did not appear to have stirred.

“Should I take the slop pail, Mr Grubb?” The boy had entered the room behind him.

Grubb nodded absently and slouched over to the cot. Then he remembered the food tray and nodded towards it. “Best put that on the stool over there. He’ll still be wanting his breakfast, like as not.”

Adkins picked up the tray and moved to obey the attendant’s instructions.

Grubb leaned over the bed. He sniffed, suddenly aware that the room harboured a strange odour that he hadn’t noticed before. The smell seemed oddly familiar, yet he couldn’t place it. No matter, the damned place was full of odd smells. One more wouldn’t make that much difference. He reached down, lifted the edge of the blanket and drew it back. As the blanket fell away, the figure on the bed moved.

And Grubb sprang back, surprisingly agile for a man of his age.

The boy yelped as Grubb’s boot heel landed on his toe. The food tray went flying, sending plate, bowl, bread and gruel across the floor.

Amos Grubb, ashen faced, stared down at the cot. At first his brain failed to register what he was seeing, then it hit him and his eyes widened in horror. He was suddenly aware of a shadow at his shoulder. Adkins, ignoring the mess on the floor, his curiosity having got the better of him, had moved in to gawk.

“NO!” Grubb managed to gasp. He tried to hold out a restraining hand, but found his arm would not respond. His limb was as heavy as lead. Then the pain took him. It was as if someone had reached inside his body, wrapped a cold fist around his heart and squeezed it with all their might.

The old man’s attempt to shield Adkins’ eyes from the image before him proved a dismal failure. As Attendant Grubb fell to the floor, clutching his scrawny chest, the scream of terror was already rising in the pot-boy’s throat.

1 (#ulink_bc4ed948-3034-51dc-a5ea-664882295b95)

There were times, Matthew Hawkwood reflected wryly, when Chief Magistrate Read displayed a sense of humour that was positively perverse. Staring up at the oak tree and its grisly adornment, he had the distinct feeling this was probably one of them.

He had received the summons to Bow Street an hour earlier.

“There’s a body …” the Chief Magistrate had said, without a trace of irony in his tone. “… in Cripplegate Churchyard.”

The Chief Magistrate was seated at the desk in his office. Head bowed, he was signing papers being passed to him by his bespectacled, round-shouldered clerk, Ezra Twigg. The magistrate’s aquiline face, from what Hawkwood could see of it, remained a picture of neutrality. Which was more than could be said for Ezra Twigg, who looked as if he might be biting his lip in an attempt to stifle laughter.

A fire, recently lit, was crackling merrily in the hearth and the previous night’s chill was at last beginning to retreat from the room.

Papers signed, the Chief Magistrate looked up. “Yes, all right, Hawkwood. I know what you’re thinking. Your expression speaks volumes.” Read glanced sideways at his clerk. “Thank you, Mr Twigg. That will be all.”

The little clerk shuffled the papers into a bundle, the lenses of his spectacles twinkling in the reflected glow of the firelight. That he managed to make it as far as the door without catching Hawkwood’s eye had to be regarded as some kind of miracle.

As his clerk departed, James Read pushed his chair back, lifted the rear flaps of his coat, and stood with his back to the fire. He waited several moments in comfortable silence for the warmth to penetrate before continuing.

“It was discovered this morning by a brace of gravediggers. They alerted the verger, who summoned a constable, who …” The Chief Magistrate waved a hand. “Well, so on and so forth. I’d be obliged if you’d go and take a look. The verger’s name is …” the Chief Magistrate leaned forward and peered at a sheet of paper on his desk: “Lucius Symes. You’ll be dealing with him, as the vicar is indisposed. According to the verger, the poor man’s been suffering from the ague and has been confined to his sickbed for the past few days.”

“Do we know who the dead person is?” Hawkwood asked.

Read shook his head. “Not yet. That is for you to find out.”

Hawkwood frowned. “You think it may be connected to our current investigation?”

The Chief Magistrate pursed his lips. “The circumstances would indicate that might indeed be a possibility.”

A noncommittal answer if ever there was one, Hawkwood thought.

“No preconceptions, Hawkwood. I’ll leave it to you to evaluate the scene.” The magistrate paused. “Though there is one factor of note.”

“What’s that?”

“The cadaver,” James Read said, “would appear to be fresh.”

The oak tree occupied a scrubby corner of the burial ground, a narrow, rectangular patch of land at the southern end of the churchyard, adjacent to Well Street. Autumn had reduced the tree’s foliage to a few resilient rust-brown specks yet, with its broad trunk and thick gnarled branches outlined against the dull, rain-threatening sky like the knotted forearms of some ancient warrior, it was still an imposing presence, standing sentinel over the gravestones that rested crookedly in its shadow. Most of the markers looked to be as old as the tree itself. Few of them remained upright. They looked like rune stones tossed haphazardly across the earth. Centuries of weathering had taken their toll on the carved inscriptions. The majority were faded and pitted with age and barely legible.

At one time, this corner of the cemetery would probably have accommodated the more wealthy members of the parish, but that had changed. Only the poor were buried here now and single plots were in the minority. The graveyard had become a testament to neglect.

And a place of execution.

The corpse had been hoisted into position by a rope around its neck and secured to the trunk of the tree by nails driven through its wrists. It hung in a crude parody of the crucifixion, head twisted to one side, arms raised in abject surrender.

Small wonder, Hawkwood thought, as his eyes took in the macabre tableau, that the gravediggers had taken to their heels.

Their names, he had discovered, were Joseph Hicks and John Burke and they were standing alongside him now, along with the verger of St Giles, a middle-aged man with anxious eyes, which Hawkwood thought, given the circumstances, was hardly surprising.

Hawkwood turned to the two gravediggers. “Has he been touched?”

They stared at him as if he was mad.

Presumably not, Hawkwood thought.

A raucous screech interrupted the stillness of the moment. Hawkwood looked up. A colony of rooks had taken up residence in the graveyard and the birds, angry at the invasion of their territory, were making their objections felt. A dozen or so straggly nests were perched precariously among the upper forks of the tree and their owners were taking a beady-eyed interest in the proceedings below. The evidence suggested that the birds had already begun to exact their revenge. They’d gone for the tastiest morsels first. The corpse’s ragged eye sockets told their own grisly story. A few of the birds, showing less reserve than their companions, had begun to edge back down the branches towards the hanged man’s body in search of fresh pickings. Their sharp beaks could peck and tear flesh with the precision of a rapier.

Hawkwood picked up a dead branch and hurled it at the nearest bird. His aim was off but it was close enough to send the flock into the air in a clamour of indignation.

Hawkwood approached the tree. His first thought was that it would have taken a degree of effort to haul the dead man into place, which indicated there had been more than one person involved in the killing. Either that, or an individual possessed of considerable strength. Hawkwood stepped closer and studied the ground around the base of the trunk, careful where he placed his own feet. The previous night’s rain had turned the ground to mud. But earth was not made paste solely by the passage of rainwater. Other factors, Hawkwood knew, should be taken into consideration.

There were faint marks; indentations too uniform to have been caused by nature. He looked closer. The depression took shape: the outline of a heel. He circled the base of the oak, eyes probing. There were more signs: leaves and twigs, broken and pressed into the soil by a weight from above. They told him there had definitely been more than one man. He paused suddenly and squatted down, mindful to avoid treading on the hem of his riding coat.

It was a complete impression, toe and heel, another indication that at least one of Hawkwood’s suspicions had been proved correct. Hawkwood was an inch under six feet in height. He placed the base of his own boot next to the spoor and saw with some satisfaction that his own foot was smaller. The depth of the indentation was also impressive.

Hawkwood glanced up. He found that he was standing on the opposite side of the tree to the body. The first thing that caught his attention was the rope. It was dangling from the fork in the trunk, its end grazing the fallen leaves below. The noose was still secured around the neck of the deceased.

In his mind’s eye, Hawkwood re-enacted the scene and looked at the ground again, casting his eyes back and to the side. There was another footprint, he saw, slightly off-centre from the first. It had been made by someone planting his feet firmly, digging in his heel, taking the strain and pulling on the rope. The indication was that he was a big man, a strong man. There were no other prints in the immediate vicinity. The hangman’s companions would have been on the other side of the tree, hammering in the nails.

Hawkwood stood and retraced his steps.

He looked up at the victim then turned to the gravediggers.

“All right, get him down.”

They looked at him, then at the verger, who, following a quick glance in Hawkwood’s direction, gave a brief nod.

“Do it,” Hawkwood snapped. “Now.”

It took a while and it was not pleasant to watch. The gravediggers had not come prepared and thus had to improvise with the tools they had to hand. This involved hammering the nails from side to side with the edge of their shovels in order to loosen them enough so that they could be pulled out of the oak’s trunk. The victim’s wrists did not emerge entirely unscathed from the ordeal. Not that the poor bastard was in any condition to protest, Hawkwood reflected grimly, as the body was lowered to the ground.

Hawkwood stole a look at Lucius Symes. The verger’s face was pale and the gravediggers didn’t look any better. More than likely, their first destination upon leaving the graveyard would be the nearest gin shop.

Hawkwood examined the corpse. The clothes were still damp, presumably from last night’s rain, so it had been up there a while. It was male, although that had been obvious from the outset. Not an old man but not a boy either; probably in his early twenties, a working man. Hawkwood could tell that by the hands, despite the recent mauling they had received from the shovels. He could tell from the calluses around the tips of the fingers and from the scar tissue across the knuckles; someone who’d been in the fight game, perhaps. It was a thought.

“Anyone recognize him?” Hawkwood asked.

No answer. Hawkwood looked up, saw their expressions. There were no nods, no shakes of the head either. He looked from one to the other. No reaction from the verger, just a numbness in his gaze, but he saw what might have been a shadow move in gravedigger Hicks’ eye. A flicker, barely perceptible; a trick of the light, perhaps?

Hawkwood considered the significance of that, placed it in a corner of his mind, and resumed his study.

At least the manner of death was beyond doubt: a broken neck.

Hawkwood loosened the noose and removed the rope from around the dead man’s throat. He stared at the necklace of bruises that mottled the cold flesh of the victim’s neck before turning his attention to the rope knot. Very neat, a professional job. Whoever had strung the poor bastard up had shown a working knowledge of the hangman’s tool. In a movement unseen by the verger and the gravediggers, Hawkwood lifted a hand to his own throat. The dark ring of bruising below his jawline lay concealed beneath his collar. He felt the familiar, momentary flash of dark memory, swiftly subdued. Odd, he thought, how things come to pass.

Placing the rope to one side and knowing it was a futile gesture, Hawkwood searched the cadaver’s pockets. As he had expected, they were empty. He took a closer look at the stains on the dead man’s jacket. The corpse’s clothing bore the evidence of both the previous night’s storm as well as the brutal manner of death. The back of the jacket and breeches had borne the brunt of the damage, caused, Hawkwood surmised, by contact with the tree trunk as the victim was hoisted aloft. He had already seen the slice marks in the bark made by the dead man’s boot heels as he had kicked and fought for air.

There were other stains, too, he noticed, on the front of the jacket and the shirt beneath. He traced the marks with his fingertip and rubbed the residue across the ball of his thumb.

Hawkwood examined the face. There was congealed blood around the lips. Had the rooks feasted there, too?

Hawkwood reached a hand into the top of his right boot and took out his knife. Behind him, the verger drew breath. One of the gravediggers swore as Hawkwood inserted the blade of the knife between the corpse’s lips. Gripping the dead man’s chin with his left hand, Hawkwood used the knife to prise open the jaws. He knelt close and peered into the victim’s mouth.

The teeth and tongue had been removed.

The extraction had been performed with a great deal of force. The ravaged, blood-encrusted gums told their own story. Hawkwood could see that a section of the lower jawbone, long enough to contain perhaps half a dozen teeth, was also missing. A bradawl had been used for the single teeth, Hawkwood suspected, and probably a hammer and small chisel for the rest. Hard to tell what might have been used to sever the tongue; a razor, perhaps.

The verger’s hand flew to his lips, as if seeking reassurance that his own tongue was still in situ. He stared at Hawkwood aghast. “What does it mean? Why would they do such a thing?”

Hawkwood wiped the blade on his sleeve and returned it to his boot. He looked down at the corpse. “I would have thought that was obvious.”

The three men stared back at him.

Hawkwood stood up and addressed the verger. “Your most recent burial – where was it?”

Verger Symes looked momentarily confused at the sudden change of tack. His face lost even more colour. “Burial? Why, that would be … Mary Walker. Died of consumption. We buried her yesterday.” The verger glanced at the two gravediggers, as if seeking confirmation.

It was the older man, Hicks, who nodded. “Four o’clock, it were, just afore the rain came.”

“Where?” Hawkwood demanded.

Hicks jerked a thumb. “Over yonder. Top o’ the pile, she was.”

A sinking feeling began to stir in Hawkwood’s belly.

“Show me.”

The gravedigger led the way across the burial ground towards a large patch of shadow close to the boundary of the churchyard, and pointed to a dark rectangle of freshly turned soil.

“How deep was she?” Hawkwood asked.

The two gravediggers exchanged meaningful glances.

Not deep enough, Hawkwood thought.

“All right, let’s take a look.”

The verger stared at Hawkwood in disbelief and horror.

“I’d step away, if I were you, Verger Symes,” Hawkwood said. “You wouldn’t want to get your shoes dirty.”

Blood drained from the verger’s face. “You cannot do this! I forbid it!”

“Protest duly noted, Verger.” Hawkwood nodded at Hicks. “Start digging.”

Hicks looked at his partner, who looked back at him and shrugged.

The shovels bit into the soil in unison.

At that moment Hawkwood knew what they would find. He could tell from the expressions on the faces of the gravediggers that they knew too. He had the feeling even Verger Symes, despite his protestation, wasn’t going to be surprised either.

In the event it took less than six inches of topsoil and a dozen shovel loads to confirm it.

There was a dull thud as a shovel struck wood. They used the edges of the shovels to scrape the soil away from the top of the coffin. What was immediately apparent was the jagged split in the wood halfway down the thin coffin lid.

“Good God, have you no pity?” The verger made as if to place himself between Hawkwood and the open grave.

“If I’m wrong, Verger Symes,” Hawkwood said, “I’ll buy your church a new roof. Now, stand aside.” He nodded to Hicks. “Open it up.”

Hicks glanced at his partner, who looked equally uncomfortable.

“Give me the bloody shovel,” Hawkwood held out his hand.

Hicks hesitated, then passed it over.

The three men watched as Hawkwood inserted the blade of the shovel under the widest end of the lid and pressed down hard. His effort met with little resistance. Other hands had already rendered the damage. The cheap lid splintered along the existing split with a drawn-out creak. Hawkwood handed the shovel back to its owner, gripped the edges of the shattered lid and lifted.

The verger swallowed nervously.

Hawkwood knelt, reached inside the coffin and lifted out the crumpled fold of cloth.

The burial shroud.

Burial plots were at a premium in London and mass graves were common in many parishes. It was often impossible to dig a fresh grave without disturbing previously buried corpses. The pit at St Giles in the Fields was a prime example where, for years, rows of cheap coffins had been piled one upon the other, all exposed to sight and smell, awaiting more coffins which would then be stacked on top of them. The depths of the pits could vary and coffins weren’t always used. A year or two back, in St Botolph’s, two gravediggers had died as a result of noxious gases emanating from decomposing corpses. Graves were often kept open for weeks until charged almost to the surface with dead bodies. In many instances the top layer of earth was only a few inches deep so that body extremities could sometimes poke through the soil.

Which made it easy for the body stealers.

Hawkwood left the gravediggers to fill in the hole and retraced his steps back to the murder scene. He looked down at the corpse and then at the grubby shroud in his hand.

Strictly speaking, bodies were not considered property. Burial clothing, however, was a different matter. Steal a corpse and you couldn’t be done. Steal clothing or a shroud or a wedding ring and that was a different matter. That carried the punishment of transportation. Whoever had ransacked this grave had been careful.

Which begged the obvious question.

Why leave the dead man’s corpse behind? Why wasn’t this one bound for the anatomist’s table as well? The dead man was relatively young and, other than the obvious fact that he was lifeless, he appeared to be in good physical shape. He should have been a prime candidate for any surgeon’s anatomy class. The corpses of well-built men were always in demand, for, with the skin stripped away, they could be used to display muscles to their best advantage. To any self-respecting body stealer, this wasn’t just a cadaver, this was serious cash-in-hand.

There was the soft pad of footsteps from behind. It was the verger.

“How many?” Hawkwood asked.

The verger bit his lip. “Four in the last two weeks, including the Walker woman. The other three were all male.”

Hawkwood said nothing and reflected on the speed of the corpse’s transformation from Mary Walker to the Walker woman. “What about a night watchman?”

Verger Symes shrugged. “It’s true we have employed them in the past, and it makes a difference for a time. The snatchers go elsewhere: St Luke’s or St Helen’s. But then the watchman becomes complacent and relaxes his vigilance, usually with the aid of a bottle, and the stealings begin again. We are not a wealthy parish, Officer Hawkwood.”

It was not an uncommon story.

The number of graveyards in the capital that had escaped the attention of the sack-’em-up men could be counted on the fingers of one hand. Deterrents had been tried – night watchmen, lamps, dogs, even concealed spring guns – but to little avail.

The wealthy could inter their dead in deeper graves, in family mausoleums and private chapels or beneath heavy, immovable headstones, encasing the remains in substantial coffins, either lead-lined or made entirely of metal. The poor could not afford such luxuries. They did their best, mixing sticks and straw with the grave soil for example, in the vain hope that the resulting fibres would choke the stealers’ wooden shovels. Paupers’ graves were easy targets.

“Can I ask you a question, Officer Hawkwood?” The verger looked pensive. “When I enquired earlier why anyone would do such a terrible thing – murder a man, then cut out his tongue – you said it was obvious. I don’t understand.”

Hawkwood nodded. “Same reason they didn’t take this body away with the other one. It was left here for a purpose.”

“Purpose?”

Hawkwood returned the verger’s gaze.

“It’s meant as a warning.”

“You think that’s why they left the body? As a warning?”

James Read asked the question with his back to the room. He was gazing out of the window, looking down into Bow Street. It was early. The Public Office on the ground floor was not due to open for over an hour. Outside, however, the roads were already busy with morning traffic. The click-clack of hooves and the rattle of carriage wheels could be heard, along with the cries of street vendors as they made their way to and from Covent Garden, barely a stone’s throw away round the corner at the end of Russell Street.

The fire, still crackling in the grate, had raised the room’s temperature considerably since Hawkwood’s last visit. James Read did not like the cold so he was studying the oppressive late November sky with no small degree of despair. He suspected that the weather was about to take a turn for the worse. There was a sullen quality in the air that hinted of yet more precipitation, possibly sleet, and that probably meant the early arrival of winter snow. He sighed, shivered in resigned acceptance, and turned towards the fire’s warming embrace.

“That was my first thought,” Hawkwood said.

Knowing James Read’s propensity for an open fire, Hawkwood had wisely left his coat in the ante-room under the eye of Ezra Twigg. He was glad he had done so. He would be roasting otherwise.

“You base that on the manner of death and the removal of the dead man’s tongue, I presume?”

Hawkwood nodded. “The gravediggers and the verger got a good look. It’ll be all round the parish by midday. If it isn’t already.”

“I would have thought the crucifixion would have sufficed,” James Read said. “The tongue seems rather excessive. Not to mention the teeth. You have thoughts on the teeth?”

“Waste not, want not,” Hawkwood said dispassionately. “The body and the tongue were left as a warning. The teeth were taken for profit.”

A fine profit, too, if one had the stomach for it. Most body stealers had. It was a lucrative sideline. Many resurrection men removed the teeth from corpses before delivering their merchandise to the anatomists. A good set could fetch five guineas if you knew your market.

“As I said: excessive.”

“Not if you really want to put the fear of God into your rivals,” Hawkwood said.

The Chief Magistrate frowned. “Which would indicate a serious escalation in violence.”

“They’re making their mark,” Hawkwood said. “Staking their territory. The Borough Boys will be looking to their laurels.”

The Borough Boys had long been the capital’s most notorious team of resurrectionists. They plied their trade mostly around Bermondsey but supplemented their incomes by regular forays north of the river. Up until now they had ruled the roost, but a rivalry had begun to develop. There were rumours of a new gang based along the Ratcliffe Highway, whose members had a mind to deter all the other body stealers from entering their domain by whatever means necessary. Fear and intimidation were their watchwords. Unbeknownst to the majority of respectable citizens, deep in the city’s shadows and the gutters a vicious war was being waged.

“What about the deceased?” Read asked. “Do we know his identity?”

“There’s a possibility his name is Edward Doyle.”

The Chief Magistrate raised an eyebrow.

“Hicks, one of the gravediggers told me. He denied knowledge at first, but then had a change of heart after he’d taken a closer look at the face second time around, so he said.”

James Read kept his eyebrow raised.

“I wasn’t satisfied with his first answer. I pressed him on it.”

“I’ve always admired your powers of persuasion, Hawkwood,” Read said drily. “So, you think he was involved?”

Hawkwood shook his head. “In the murder? No, his shock was genuine. In planning the removal of the woman’s body? Maybe. Proving it might be difficult.”

“So your thought is that he tipped off Doyle there was a newly buried body. Doyle turned up to collect it and ran into a rival gang who stole the body, killed Doyle and left his body on display?”

“I’d say so,” Hawkwood agreed.

That James Read expressed no concern at the gravedigger’s alleged involvement came as no surprise to Hawkwood. It was common knowledge that most resurrection men plied their business with the connivance of those connected to the burial trade, be they undertakers or gravediggers. It wasn’t unheard of for those who dug the graves to be personally involved in exhumations. After all, they knew where the bodies were buried, literally. A common ruse was for gravediggers to let slip to interested parties that certain cadavers, by prior arrangement, were not in the coffins that had been recently buried but left instead on top of the casket, hidden under a thin layer of loose earth just below the surface, ready for retrieval.

“What else do we know about Doyle?” Read asked.

“Hicks thinks he may have been a porter, one of the Smithfield lot.”

“And?”

“And nothing. That was all he knew.”

Read sucked in his cheeks. “What does that leave us?”

“Not much,” Hawkwood admitted. “But it’s all I’ve got. If he does work out of Smithfield, the odds are he’ll have had a regular watering hole close by, maybe one of those drinking dens up on Cow Street. And if he was a resurrectionist on the side, it’s even more likely. From what I’ve heard, most of the bastards spend their takings on rotgut.”

The Chief Magistrate bit his lip. “I take it you intend paying the area a visit?”

“I thought I might,” Hawkwood said. “Ask around. See what I can dig up.” Hawkwood kept his face straight.

“Thank you, Hawkwood. Most amusing.” The Chief Magistrate returned to his desk and took his seat. “But, before you do, I’ve another pressing matter that requires immediate attention. I’m afraid to say this is turning out to be a most memorable morning. While you were investigating the incident in Cripplegate, I received word of another murder, a most curious occurrence, not to mention a most intriguing coincidence, given your recent encounter with death and divinity.”

Hawkwood wasn’t sure if this was another example of the Chief Magistrate’s mordant wit, or how he was expected to respond, if at all. He decided to wait and see.

“The conveyor of the information was in a severe state of agitation, understandably. As a result the details are somewhat incomplete. We do know the victim is a Colonel Titus Hyde.”

“Army?” Hawkwood frowned.

The Chief Magistrate nodded. “Indeed, which is why I felt it appropriate that an officer with your background should initiate the investigation. Bizarrely, we were also provided with the murderer’s identity, and his address. The perpetrator would appear to be a man of the cloth; a Reverend Tombs.”

“A parson?” Hawkwood couldn’t mask his surprise.

“I’ve dispatched constables to the parson’s house. It’s doubtful he’ll be there, of course. Most likely he’s gone to ground somewhere, but it’s the logical place to start looking for him. I’d like you to visit the scene of the crime.”

The expression on the Chief Magistrate’s face told Hawkwood there was more to come. “Which was where?”

The Chief Magistrate pursed his lips. “Ah, again, that is another perplexing factor. The killing took place last night, or rather in the early hours of this morning, in Moor Fields. The exact location …” the Chief Magistrate paused “… was Bethlem Hospital.”

And there it was. Hawkwood stared at the Chief Magistrate. Save for the ticking of the clock in the corner and the crackle of burning wood in the grate, the room had gone uncannily silent.

Because not many people called it that.

In the same way the Public Office was known, at least to the personnel who worked there, by a nickname, the Shop, so too was Bethlem Hospital; and not just by its staff, but by the entire city, if not the entire nation. Bethlem had been its founding name, but it had another: a single word synonymous with incarceration, misery and madness.

Bedlam.

2 (#ulink_dc232259-e101-53f0-a186-e02564dae259)

Hawkwood stared stonily through the railings at the state of the building he was about to enter. Despite having dominated the area for centuries and become ingrained in the public consciousness, the place still held a morbid fascination, even if it was collapsing into ruin.

The original façade had been some five hundred feet in length, modelled, so it was said, on the Tuileries Palace in Paris. In its prime, the building must have been a magnificent sight.

Not any longer. The place had been falling apart for years, subsidence and rot having taken its toll. The east wing had already been demolished, following a damning surveyor’s report. Only half of the original building remained and that was little more than a shell. It was no longer a palace but a slum, as shoddy and as run down as the houses and second-hand furniture shops that occupied the narrow streets around it.

Hawkwood had never visited the hospital, though he’d lost count of the times he’d walked past the place, and he couldn’t recall a single occasion when he hadn’t experienced a dark sense of foreboding. Bethlem had that effect.

He glanced up. Above him, surmounting the posts either side of the entrance gates, were two reclining stone statues. Both were male, naked and badly eroded, victims of more than a century’s exposure to wind and rain and the capital’s filthy air. The wrists of the right-hand figure were linked by a thick chain and heavy manacles. The statue’s head was tilted, the carved mouth was open in a silent scream of despair, as if warning passers-by of the cruel reality concealed behind the gates.

He heard laughter, the happy sound at once at odds with the cheerless surroundings. He looked over his right shoulder. There’d been a time when Moor Fields had been counted among the capital’s greatest visitor attractions, its landscaped lawns and wide walkways framed by neat railings and tall, elegant elm trees inspiring tributes from artists and poets.

Most of that had long since disappeared. What had once been a smooth, green, manicured meadow was now a meagre desert of bare earth and weeds. What remained of the railings were bent and broken. The trees that lined the pathways looked listless and unkempt in the dull morning light. Parts of the encompassing lawn had suffered from chronic subsidence, creating, after stormy nights, rainwater-filled depressions. It was from the edge of one of these shallow ponds that the laughter had originated. Two small boys were playing with a toy galleon, re-enacting some naval engagement, totally immersed in their imaginary battle, oblivious to the incongruity of the moment.

Hawkwood turned away. Climbing the steps, he entered the courtyard and made his way across to the hospital’s main entrance. There were niches either side of the door. In each one there stood a painted wooden alms box. One was in the shape of a male youth. The other was a bare-breasted female figure. Above them was an inscription encouraging the visitor to make a contribution to the hospital funds. Ignoring the carved inducement, Hawkwood pulled on the bell, and waited.

A small hatchway was set in the door. The hatch cover slid back and a pair of hooded eyes appeared in the opening.

“Officer Hawkwood. Bow Street. Here to see Apothecary Locke.”

The face disappeared from view and the hatch slammed shut. There was the sound of a bolt being released and the door swung open.

Inside, the building was pungent with the smell of piss and shit and damp straw. Hawkwood had skirted Smithfield on his way to the hospital and the reek from the piles of horse, cattle and sheep dung left behind from the previous day’s market hung in the air, strong enough to make the eyes water. For a moment he thought he might have tracked something in on the sole of his boot and he lifted his foot to check. Nothing; the fetid odour must be part of the building’s fabric.

The door closed heavily behind him.

A cleaning operation was in full spate. Mops and pails were in liberal use in a bid to restore some semblance of order after the night’s storm. Judging by the amount of dark seepage still trickling down the walls and across the uneven floor, it looked like a losing battle. Despite the activity, the atmosphere appeared subdued. Most of the workers were toiling in silence. Present among the cleaning gang were several unsmiling men in blue coats. Hospital staff, Hawkwood supposed.

The porter who had let him in, a thin man with a long nose and lugubrious expression, stepped away from the door. “Apothecary’s in ’is office. I’ll have someone take you up.” The porter caught the eye of one of the blue-coated men and beckoned. “Mr Leech? Officer Hawkwood. He’s from Bow Street.”

The blue-coated attendant nodded. “Been expectin’ you. Follow me.”

Hawkwood fell in behind his guide as he climbed the stairway to the first-floor landing. Conditions here didn’t look to be any better than those at ground level.

The upstairs gallery ran the full length of the building, divided at intervals by floor-to-ceiling openwork grilles. The left-hand side of the gallery was occupied by cells, so the grey morning light could only enter by the windows along the opposite north wall. It barely supplemented the inadequate candle glow.

The smell was worse than down below and when he passed one of the open cell doors and saw what lay in the cramped room beyond, Hawkwood understood why.

There was a low wooden cot with a straw-filled mattress. Seated upon the mattress was a man, or at least what appeared to be a man. He was desperately thin. His face was as pale and as pointed as a shrew’s. A soiled woollen blanket covered the lower half of his body except for his feet, which protruded from beneath the filthy material like two pale white slugs. It was clear that beneath the covering the patient was naked from the waist down. He was wearing a grey shirt and yellow handkerchief around his neck but it was his headwear that caught Hawkwood’s attention: a red skullcap, beneath which was wrapped a loose, once-white bandage. Hawkwood found himself transfixed, not just by the man’s expression, which was one of abject misery, but by the iron harness fastened around his chest and upper arms and the iron ring around his throat. The ring was attached by a chain to a wooden pole that ran vertically from the corner of the cot to a bracket in the ceiling. As the blanket slipped off one scabby leg Hawkwood saw that there was another strap around the man’s ankle, attached by a second chain secured to the edge of the cot. It was clear from the state of him that the man was sitting in his own waste.

The attendant spotted the revulsion on Hawkwood’s face and followed the Runner’s gaze. A sneer creased his lip. “What you lookin’ at, Norris?”

Hawkwood watched as a single tear trickled slowly down the shackled man’s emaciated cheek.

The attendant seemed not to notice but turned abruptly and continued along the gallery. Hawkwood tore his eyes away from the open door and followed his guide.

Most of the cells they passed were occupied, with the majority housing more than one patient. It was clear that Norris wasn’t the only one who was chained up. Even in the darkened interiors Hawkwood could see that a number of patients, both male and female, were similarly restrained. Several more blue-coated keepers were in attendance, some supervising patients or else engaged in cleaning duties.

The attendant led Hawkwood along the wing, finally stopping outside a door with a brass plate upon which was etched Apothecary. Leech knocked on the door and awaited the summons from within. When it came, he opened the door, spoke briefly to the occupant then indicated for Hawkwood to enter.

It was an austere room, darkly furnished and, like the rest of the building, it carried an overwhelming air of dampness and decay. There were a great number of books. On the wall immediately behind the desk were tier upon tier of shelves, filled with rolled documents. Patients’ records, Hawkwood assumed.

Apothecary Robert Locke was not the authoritative figure Hawkwood had been expecting. He had envisioned someone middle-aged, with an academic air. Locke, on the other hand, looked to be in his mid thirties, stocky, with a studious countenance and a slight paunch. His youthful face, framed by a pair of small, round spectacles, looked pale and drawn. He turned from the window where he had been standing in thoughtful pose and greeted Hawkwood with a formal, yet hesitant nod.

“Your servant, Officer Hawkwood. Thank you for coming. I’ve asked Mr Leech to remain, by the way, as it was he who admitted the Reverend Tombs into the hospital last night.”

Hawkwood said nothing. He looked from the keeper to the apothecary. Both eyed him expectantly.

“Forgive me,” Hawkwood said. “I was wondering why I was instructed to ask for the apothecary. Why am I not seeing the physician in charge, Dr Monro?”

A look passed between the two men. Apothecary Locke pursed his lips. “I’m afraid Dr Monro is unavailable. His responsibilities cover a rather broad – how shall I put it? – canvas. He has other duties that also demand his attention.”

What might have been a smirk flickered across Attendant Leech’s face.

“And yet he’s in charge of the hospital, and therefore of the patients’ welfare, is he not?”

Locke nodded. “That is so. However, he is by title only the visiting physician and thus is not required to attend the premises on a daily basis. He oversees prescriptions to patients two days a week and attends the governors’ sub-committee meeting on Saturday mornings.”

“And the rest of the time?”

There was just the slightest hesitation, barely noticeable, but it was there nevertheless.

“I understand the majority of his time is spent at his academy, commissioning and, er … setting up his exhibits.”

“His what?” Hawkwood wondered if he’d heard correctly.

“His paintings, Officer Hawkwood. Dr Monro is a respected patron of the arts. I understand Mr Turner used to be one of his many protégés.”

“Turner?”

“The artist. He has received many plaudits for his works. His forte is landscapes, I believe.”

“I know who Turner is,” Hawkwood snapped.

The apothecary stiffened and blinked. The look that flickered across the bespectacled face suggested that Locke’s expectation of a Bow Street emissary had probably run to a ponderous, black-capped, blue-waistcoated conductor of the watch with an ingratiating manner and a pot-belly. Patently what the apothecary had not made provision for was an arrogant, long-haired, scar-faced, well-dressed ruffian with a passing knowledge of the arts.

For his part, Hawkwood recalled Locke’s initial response to his question. The apothecary’s turn of phrase had seemed a little odd at the time, as had the emphasis on the word “canvas”. All was now becoming clear. He hadn’t imagined Attendant Leech’s smirk. The unmistakable whiff of resentment hung in the air. There might be more to this timid-faced apothecary than he had first thought. And that was certainly an avenue worth exploring.

“Forgive me, Doctor, it just seemed curious to me that the hospital’s chief physician would appear to spend rather more time with his paintings than his patients. However, there’s another doctor on the staff, I believe: Surgeon Crowther? Or have his duties taken him elsewhere, too?”

Hawkwood allowed just the right amount of sarcasm to creep into his voice. His tactic was rewarded. This time, the apothecary’s reaction was less restrained. He flushed and coughed nervously.

Over his shoulder, Hawkwood heard Attendant Leech shift his feet.

Locke’s eyes flickered towards the sound. “I’d be obliged, Mr Leech, if you would be so good as to wait outside.”

The attendant hesitated then nodded. Locke waited until the door had closed. He turned back to Hawkwood. Removing his spectacles, he extracted a handkerchief from his pocket and began to polish each lens. “I regret that Surgeon Crowther is …” the apothecary pursed his lips “… indisposed.”

“Really? How so?”

Locke placed his spectacles back on his nose and tucked away his handkerchief.

“The man’s a drunkard. I haven’t seen him for three days. I suspect he’s either at home soaking up the grape or lying in a stupor in some Gin Lane grog shop.”

This time there was no mistaking the edge in the apothecary’s voice. It was sharp enough to cut glass. “Which is why you are talking to the apothecary, Officer Hawkwood. Does that answer your question? Now, perhaps you would care to see the body?”

Attendant Leech led the way.

As they were going down the stairs, the apothecary paused as if to collect his thoughts. Allowing Leech to get a few steps ahead of them, he took a deep breath. “My apologies, Officer Hawkwood. You must think me indiscreet. I fear I rather let my tongue run away with me, but it has been somewhat difficult of late, what with the surveyors’ final report and the notice and so forth.”

“Notice?” Hawkwood said.

“The building’s been condemned. Hadn’t you heard?” The apothecary made a face. “Some would say not before time. You saw that the east wing’s already gone? That used to house the male patients. Since its destruction we’ve had to move the men into the same gallery as the women; not the most suitable arrangement, as you may imagine. It’s fortunate we’re not operating at full capacity. When I started there were double the number of patients there are now. Hopefully we’ll have more room when we move to our new quarters, though goodness knows when that will be.”

They descended a few more steps, then Locke said, “A site has been procured, at St George’s Field. Plans have been agreed, though there’s been some doubt about the funding. You may have seen the subscription campaign for donations in The Times? Ah, well, no matter. Unfortunately, attention has been diverted to the New Bethlem very much at the expense of the old one. We have been abandoned, Officer Hawkwood. Some might even say betrayed. Which accounts for the deplorable state of repairs you see before you.”

They reached the bottom of the stairs. A few of the keepers nodded as the apothecary passed. Most of them ignored him and continued to swab the floor.

“I’ve a hundred and twenty patients in my care, male and female, and less than thirty unskilled staff to tend them. That includes attendants, maidservants, cooks, washerwomen and gardeners – though God knows there’s scant need for their services. I’m required to sleep on the premises and to make rounds every morning, dispense advice and medicines and direct the keepers in the management of the patients. Note that I said ‘direct’, Officer Hawkwood. I have no authority over them, save in the supervision of their daily schedule. I’m not permitted to dismiss or even discipline the keepers, despite the fact that many of them are frequently the worse for drink. My complaints continue to fall on deaf ears. Wait, did I say ‘deaf’? Absent would be a better word.”

They had left the rattle of mops and pails behind them. The damp smell, however, seemed to follow them along the corridor.

The apothecary’s nose twitched. “Is this your first visit, Officer Hawkwood?”

Admitting that it was, Hawkwood wondered where the question was leading.

“And what was the first thing that struck you when you walked through the door? I beg you to be truthful.” As he spoke, the apothecary sidestepped nimbly around a puddle.

“The smell,” Hawkwood said, without hesitation.

The apothecary stopped and turned to face him. “Indeed, Officer Hawkwood, the smell. The place reeks. It reeks of four centuries of human excreta. Bethlem is a midden; it’s where London discharges its waste matter. This is the city’s dung heap and it has become my onerous duty to ensure that the reek is contained.”

Hawkwood knew it was going to be bad. He’d seen it in the pallor on Locke’s face, in the expression of dread in the young apothecary’s eyes, in the quickening of his breath and the faint yet distinct tremor in Leech’s hand as the keeper had unlocked the door.

The window shutters were open but, as the morning sky was overcast, the room was suffused in a spectral half-light. When he entered, Hawkwood felt as if all the warmth had been sucked from his body. He wondered whether that was due to the temperature or his growing feeling of unease. He’d seen death many times. He’d witnessed it taking place and had visited it upon his enemies, both on the battlefield and elsewhere, and yet, as soon as his eyes took in his surroundings, he knew this was going to be different to anything he had experienced.

He heard the apothecary murmur instructions to Attendant Leech, who began to move around the room lighting candle stubs. Gradually, the shadows started to retreat and the cell’s layout began to take form, as did its contents.

It was not one room, Hawkwood saw, but two, separated by a low archway, as if two adjoining cells had been turned into one by removing a section of the intervening wall. Even so, with its cold stone floor and dark, dripping walls, the cell resembled a castle dungeon more than a hospital room. Hawkwood recalled a recent investigation into a forgery case which had taken him to Newgate to interview an inmate. The gaol was a black-hearted, festering sore. The cells there had been dank hellholes. The design of this place, he realized, looked very similar, even down to the bars on the windows.

In the immediate area, there were a few sticks of rudimentary furniture: a table, two chairs, a stool, a slop pail in the corner, close to what looked to be the end of a sluice pipe, and a narrow wooden cot pushed against the wall. On top of the cot could be seen the vague shape of a human form covered by a threadbare woollen blanket.

The apothecary approached the cot. He straightened, as if to gather himself. “Bring the candle closer, Mr Leech, if you please.” He turned to Hawkwood. “I must warn you to prepare yourself.”

Hawkwood had already done so. The pervasive scent of death had transmitted its own warning. At the same time he wondered if the dampness in the cell was a permanent phenomenon or solely a consequence of the previous night’s deluge. He could hear a faint tapping sound coming from somewhere close by and concluded it was probably rainwater dripping through a hole in the ceiling.

Locke lifted the corner of the blanket and pulled it away. Even with Leech holding the candle above the cot, in the dim light it took a second or two for the ghastly vision to sink in.

Hawkwood had seen the injuries suffered by soldiers. He’d seen arms and legs slashed and sliced by sword and bayonet. He’d seen limbs shattered by musket balls and he’d seen men turned to gruel by canister. But nothing he had seen could be compared to this.

The corpse, dressed only in undergarments, lay on its back. The body appeared to be unmarked, except for one incontrovertible fact.

It had no face.

Hawkwood held out his hand. “Give me the light.”

Leech passed over the candle. Hawkwood crouched down. From what he could see, every square inch of the corpse’s facial skin from brow to chin had been removed. All that remained was an uneven oval of raw, suppurating flesh. The eyelids were still in place, as were the lips, though they were thin and bloodless and reminded Hawkwood of the body he’d examined first thing that morning. Unlike that corpse, however, this body still possessed its tongue and teeth.

Beside him, the apothecary was staring at the corpse as though mesmerized by the epic brutality of the scene. Reaching for his handkerchief, Locke polished his spectacles vigorously and perched them back on his nose. “From what I can tell, the first incision was probably made close to the ear. The blade was then drawn around the circumference of the face, with just sufficient pressure to break through the layers of the epidermis. The blade was then inserted under the skin to pare it away, separating it from the underlying muscle in stages.” The apothecary grimaced. “It would be rather similar to filleting a fish. Eventually, this would enable him to peel and lift the entire facial features off the skull, probably in one piece, like a mask …” Locke paused. “It was skilfully done, as you can see.”

“Where the devil would a parson pick up that sort of knowledge?” Hawkwood said.

The apothecary looked puzzled. “Parson?”

“Priest, then. Reverend Tombs – isn’t that his name?”

The apothecary stiffened. He turned and threw a glance at the keeper, his eyebrows raised in enquiry. The keeper reddened and shook his head. The apothecary’s jaw tightened. He turned back. “I fear there has been a misunderstanding.”

Hawkwood looked at him.

Locke hesitated, clearly uncomfortable.

“Doctor?” Hawkwood said.

The apothecary took a deep breath, then said, “It wasn’t the priest who perpetrated this barbaric act.”

Hawkwood looked back at him.

“Reverend Tombs was not the murderer, Officer Hawkwood. He was not the one who wielded the knife. He couldn’t have done.” Locke nodded towards the body on the cot. “Reverend Tombs was the victim.”

3 (#ulink_09453a43-f7e9-55ef-9295-eaef1627ce6a)

The apothecary looked down at the corpse and gave a brief shake of his head, as if to deny the bloody reality that lay before him.

“I confess, we took it to be the colonel’s body at first. It seemed the obvious conclusion in the light of Mr Grubb’s assurance that he’d escorted Reverend Tombs out of the building, or at least the person he assumed to be the reverend. It was only when I made a closer examination that I became aware of the deception. Unfortunately, we’d already sent word to Bow Street by then. I had thought, wrongly, that Mr Leech had informed you of the error upon your arrival.”

Locke lifted the corpse’s arm by the wrist and traced a path across the unmarked knuckles. “The colonel had a scar across the back of his right hand, just here. He told me it was the result of an accident during his army service. It was quite distinct and yet, as you can see, there is no scar.” The apothecary let the arm drop back on to the cot. “This is not Colonel Hyde.”

“But it is the Reverend Tombs? You’re sure of that?”

Locke nodded solemnly. “Quite sure.”

“Did he have scars too?”

Hawkwood couldn’t help injecting a note of sarcasm into his enquiry. To his surprise, Locke showed no adverse reaction to the retort but stated simply, “As a matter of fact, he did.” The apothecary met Hawkwood’s unspoken question by pointing to his own cheeks and jaw, the areas of the corpse’s face that had been excised. “The worst of them were on his face. Here and here. The minor ones are still visible there behind his left ear, if you look closely.”

Hawkwood turned to Leech. “You escorted Reverend Tombs to the room? What time was this?”

“It’d be about ten o’clock,” Leech said. “It were still rainin’ cats and dogs.”

“After you left him, what did you do?”

Leech shrugged. “Finished me rounds, went back upstairs.”

“And the key?”

“Left it on the ’ook in the keepers’ room with the rest of ’em.”

“And this … Grubb, he’d have taken the key to let the priest out?”

Leech nodded. “That’s right.” The attendant pointed to a bell cord hanging in the corner of the room. “Soon as he ’eard the bell ring, he’d have been on ’is way.”

“And Grubb noticed nothing untoward?”

Leech shook his head. “’E never said. I saw ’im when I came on again this morning, before Adkins told ’im about the colonel’s tray not bein’ touched. Asked him how things had gone and ’e said there’d been no problems. The parson rang the bell. Grubb collected him and escorted him out.”

“I’ll need to speak with Attendant Grubb,” Hawkwood said.

Locke nodded. “Of course, though he is still convalescing.”

“Convalescing?”

“He suffered a seizure when he discovered the body. Fortunately it was not as serious as we first feared. He is feeling rather frail, however, and has not yet returned to his duties. I can take you to him.”

Hawkwood nodded and looked around the room. “Has anything been moved, Doctor?”

“Moved?” Locke frowned.

“Put back in its place. Is this how it was when Grubb found the body?”

“I believe so, yes.”

Hawkwood stared at the iron rings set into the wall above the bed. He had a sudden vision of Norris, the patient chained to the wall by his neck and ankles. He walked towards the table. In the centre of it lay a chessboard. From the position of the pieces, the game was unfinished. Hawkwood picked up one of the figures – a white knight. It was made of bone. Hawkwood had seen similar sets before, carved by French prisoners of war imprisoned on the hulks. It wasn’t uncommon for such items to appear in private homes. There were agents, philanthropists who acted on behalf of some of the more skilful artists, offering to sell their carvings on the open market for a modest, or in some cases not so modest, commission. He wondered about the provenance of this particular set as he took in the rest of the items on the table: two mugs and an empty cordial bottle. He picked up the bottle. “Curious there’s no sign of a struggle.”

Locke blinked.

“Look around, Doctor. Not a chair overturned, not so much as a bishop upended or a pawn knocked out of its square. Doesn’t that strike you as odd? You think the man just stretched out and allowed himself to be butchered? He was already dead before that was done to him. He had to be.”

Locke looked pensive. “I found no obvious signs of injury to the body – other than the trauma … damage … to the face, of course – which suggests the cause of death could have been suffocation. A sharp, swift blow to the stomach, perhaps, to incapacitate, followed by a pillow over the face. Death would occur in a matter of minutes; less, probably, if the victim was already gasping for air.”

“So he smothered him, then mutilated him? Well, that’s certainly a possibility, Doctor. So tell me: where did he get the blade?”

The question seemed to hang in the air. Locke went pale.

“I’m assuming there are rules about patients owning sharp objects, knives and such?” Hawkwood said.

Locke shifted uncomfortably. “That is correct.”

“Not even for cutting up food?”

“That is done by the keepers.”

“And razors? What about shaving?”

“The difficult patients are secured. Those of a more … placid … disposition are looked after, again by the keepers, usually with a pot-boy in attendance.”

Hawkwood saw that the apothecary was clenching and unclenching his hands.

“What is it, Doctor?”

Locke, clearly agitated, swallowed nervously. “It’s possible that I may have … ah, inadvertently, provided Colonel Hyde with the opportunity to procure the … ah, murder weapon.”

“Oh, and how is that?”

Cowed by the look in Hawkwood’s eyes, the apothecary started to knead the palm of his left hand with his right thumb. It looked as if he was trying to rub a bloodstain out of his skin. “There were occasions when I was called upon to attend the colonel in my … ah, medical capacity.”

“Really?”

“Nothing too serious, you understand: a purgative now and again, and there was the lancing of an abscess a month or so ago.” The apothecary’s voice faltered as he realized the significance of the confession.

“So you’d have had your bag with you?”

“Yes.”

“Which would have contained what, exactly?”

“The usual items: salves, pills, emetics and suchlike.”

“And your instruments?”

There was a moment’s pause before the apothecary answered. When he did so, his voice was close to a whisper. “Yes.”

“Your surgical knives, with their sharp blades? Because you’d need a knife with a sharp blade to lance an abscess, wouldn’t you, Doctor?” Hawkwood said.

The apothecary glanced towards Leech, but there was no sympathy on the attendant’s face, merely relief that someone else was in the firing line.

Hawkwood pressed home his attack. “That’s what happened, isn’t it? At some time during one of your visits to remove a boil from the colonel’s arse, he managed to steal one of your damned scalpels.”

Locke’s face crumpled.

“And you’re telling me you didn’t even notice the loss?”

Locke’s expression was one of abject misery.

Hawkwood shook his head in disbelief. “I’ve half a mind to arrest you, Doctor, though, frankly, I wouldn’t know what to charge you with – complicity or incompetence. I’m beginning to wonder what sort of place you’re running here. Good Christ, who’s in charge of your damned hospital, the staff or the lunatics?”

Locke’s cheeks coloured. His eyes, magnified by the round spectacle lenses, looked as big as saucers.

Hawkwood was aware that Attendant Leech was staring at him. Word of the apothecary’s dressing down would be all over the hospital the moment Leech left the room. He nodded towards the body and the ruin that had once been a man’s face. “How long would it have taken to do that?”

Locke took a deep breath; his lips formed a tight line. “Not long, if the murderer knew his trade.”

There was a pause.

“Well, go on, tell me,” Hawkwood said, wondering what else was to come.

“Colonel Hyde was an army surgeon. He operated in field hospitals in the Peninsula. His treatment of the wounded was, I understand …” Locke bit his lip “… highly regarded.”

“Was it indeed?” Hawkwood digested the information. Then, taking a candle from the table, he stepped through the archway into the other half of the cell.

There was another table upon which stood a jug and a washbowl. Against one wall sat a mahogany desk, a folding chair and a large wooden chest bound with brass. Looking at them, Hawkwood felt an instant stab of recognition. As a soldier he’d seen desks and chests like these more times than he cared to remember. Enter any officer’s quarters, be it in a barracks, or even a battlefield bivouac, and it would be furnished with identical items; they were standard campaign equipment. He even had a chest of his own, strikingly similar to the one here, back at his lodgings in the Blackbird tavern. It had been acquired during his time in the Peninsula, at an auction following the death of the chest’s former owner on the retreat to Corunna.

The room and its contents were at complete odds with the bare functionality of the sleeping quarters and a world apart from the conditions in which the other patients, or at least the ones he’d seen, were being kept. Those had bordered on the inhumane. By contrast this accommodation was verging on the palatial. Why should that be? Hawkwood wondered.

By far the greatest contrast lay in the collection of books and the drawings that covered the walls; several score, by Hawkwood’s rough estimate. So many, they would not have disgraced a small library. Hawkwood held the candle close and ran his eye over the serried ranks of leather-bound volumes. None of the authors’ names meant anything: Harvey, Cheselden, Hunter. Others were evidently foreign. Vesalius and Casserio appeared to be Italian, while some, like Ibn Sina and Massa, sounded vaguely Oriental. The ones in English were all similar in tone: Anatomy of the Human Body, The Motion of the Heart, The Natural History of the Human Teeth. There were others with titles in Latin. Hawkwood assumed they were medical texts, too.