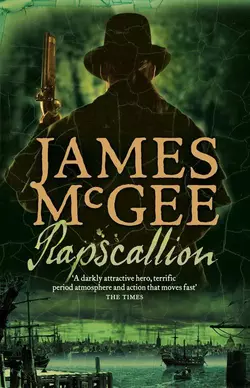

Rapscallion

James McGee

Matthew Hawkwood, ex-soldier turned Bow Street Runner, goes undercover to hunt down smugglers and traitors at the height of the Napoleonic Wars in this thrilling follow-up to Ratcatcher.For a French prisoner of war, there is only one fate worse than the gallows: the hulks. Former man-o'-wars, now converted to prison ships, their fearsome reputation guarantees a sentence served in the most dreadful conditions.Few survive. Escape, it's said, is impossible.Yet reports persist of a sinister smuggling operation within this brutal world – and the Royal Navy is worried enough to send two of its officers to investigate.But when they disappear without trace, the Navy turns in desperation to Bow Street for help. It's time to send in a man as dangerous as the prey. It's time to send in Hawkwood…

JAMES McGEE

Rapscallion

CONTENTS

Cover (#u23ed43bb-54c3-58b9-b786-36c3647c714b)

Title Page (#u01265c0f-26bf-5823-8571-ac8b4cdc7c70)

Prologue (#ud1dc87ad-012b-583b-81f1-56abfcbf7f47)

1 (#ub0c8627d-93ec-5f03-a25d-1f7269586c0f)

2 (#uf14ba2da-fec2-5f67-bb73-4eca79a160b1)

3 (#ubf87712f-0889-5518-9168-610b1553d594)

4 (#u2636eefe-a3a7-58ea-9686-e06c280db094)

5 (#u4eb2a8a8-cffe-5fcf-af51-67eb8301e994)

6 (#u967829cc-24ce-5d51-ac45-230b92535b47)

7 (#uc1e42dce-4353-5daf-bf54-dd487b7561f8)

8 (#litres_trial_promo)

9 (#litres_trial_promo)

10 (#litres_trial_promo)

11 (#litres_trial_promo)

12 (#litres_trial_promo)

13 (#litres_trial_promo)

14 (#litres_trial_promo)

15 (#litres_trial_promo)

16 (#litres_trial_promo)

17 (#litres_trial_promo)

18 (#litres_trial_promo)

19 (#litres_trial_promo)

20 (#litres_trial_promo)

21 (#litres_trial_promo)

22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Historical Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE (#ulink_19c562a8-f9f6-5995-81de-6e2205c67ce8)

Sark stopped, sank to his knees and listened, but the only sounds he could hear were the pounding of his own heartbeat and the rasping wheeze at the back of his throat as he fought desperately to draw air into his burning lungs. He tried to delay his inhalations in an attempt to slow down his breathing, but the effect was marginal. Moisture from the soggy ground had begun to soak into his breeches, adding to his discomfort. He raised himself into a squat and took stock of his surroundings, eyes probing the darkness for a familiar landmark, but to his untutored eye one stretch of featureless marshland looked much like any other.

A hooting cry came from behind and he stiffened. Owls hunted across the levels at night. Sometimes you could hear the beat of their wings if you were quiet enough. Sark remained where he was, crouched low. It had probably been an owl, but there were other creatures abroad, Sark knew, and they were hunting too.

There was movement to his left, accompanied by a soft grunt. The short hairs rose across the back of Sark’s neck and along his forearms. He turned slowly, not daring to exhale, and found himself under close scrutiny from a large sheep. For several seconds, man and beast regarded each other in eerie silence. The animal was not alone. Sark could make out at least a dozen more, huddled behind.

The ewe was the first to break eye contact. Backing off, it ambled away and began to herd its companions towards a clump of bushes. Sark breathed a sigh of relief.

Then he heard the distant baying and the bile rose into his mouth.

They were using dogs.

Sark glanced out of the corner of his eye and saw the sheep pause in their tracks as their ears picked up the unearthly ululation. Then, as if with one mind, the animals broke into a brisk trot. Within seconds they had vanished into the deepening gloom.

Sark turned and tried to locate the direction of the sound, but the darkness, allied to the dips and folds in the ground, made it difficult to pinpoint the exact bearing.

Ahead of him, the land had begun to rise. Sark inched forward, hoping the slope would provide the advantage of height and enable him to see further than his current position. Reaching the top of the bank, he elevated himself cautiously and stared back the way he had come. The first thing he saw was the bright flickering glow of a torch flame, then another, and another beyond that. From his vantage point he could see that the torchbearers were still some way off and that they were proceeding haphazardly. He suspected they were following the creek lines, but there was no doubt they were moving towards him, drawing inexorably closer with each passing second.

There were more lights in the far distance. They were no more than pinpricks, and stationary, and he guessed these were the masthead lanterns of ships moored in the estuary. He wondered briefly if he shouldn’t have been heading towards rather than away from them, but he knew that hadn’t been an option. His pursuers were sure to have cut off that line of escape.

He looked around and found he was at the edge of a dyke. The ditch stretched away from him, merging into the moonlit wetlands like a snake into the undergrowth. The smell from the bottom of the dyke was foul; a pungent, nostril-pinching mix of peat and stagnant water. There was another strong odour, too. He could see a heaped shape lying close to the water’s edge; the remains of a dead sheep. Presumably the animal had placed its foot in a rabbit-hole or some similar burrow, stumbled down the bank and become stuck in the bog, unable to extricate itself.

Sark wondered how long it had taken the beast to die. He tried to ignore the mosquitoes whining about his ears, knowing even though he could not feel their bite that they had already begun to feast upon his blood.

Another drawn-out howl came looping out of the night. Sark felt the cold hand of fear clutch his heart and he cursed his inactivity. He shouldn’t have remained so long in one place. He got to his feet and began to run.

He had a rough idea of where he was and the direction in which he was travelling. He had the vague notion that the King’s Ferry House wasn’t much more than half a mile away. If his navigation was correct and he could reach the landing and find a boat, there was a possibility that he’d be able to cross the river and hide out on the opposite shore and thus give his pursuers the slip.

Keeping low, he continued to follow the dyke’s path, ignoring the stitch in his side, which was beginning to stab at him with all the tenacity of a red-hot rapier.

Another cry sounded; human this time, not more than a few hundred yards off. Sark was uncomfortably aware that the men on his trail knew the ground far better than he did. Despite the unevenness of the terrain and the latticework of waterways that crisscrossed the island, they were catching up fast.

His foot slipped and he swore as he started to slide down the side of the gulley. The desire to enter and wade through the murky water in a bid to confuse the hounds was tempting, but he knew it would hamper his progress. All they had to do was steer the dogs along each bank and they’d soon discover where he had left the stream, and they’d pick up his trail again in no time. It was best to keep moving and try to reach the ferry landing; as dry as possible, preferably. He slithered to his feet and scrambled back up the slope.

He could hear his pursuers calling to each other now, driven by the excitement of the chase. In his mind’s eye he saw the hounds, eyes bright, tongues slavering, straining at their leashes as they followed his scent. Sark quickened his pace.

The dyke began to widen. Sark hoped it was a sign he was close to its joining with the main channel. Pressing down on the edges of his boot heels to give himself purchase, he pushed his weary, mud-splattered body towards what he hoped was his route to salvation.

There was a shout. Glancing over his shoulder, Sark’s stomach lurched when he saw how quickly the gap had shortened. The torches were a lot closer. Beneath the fiery brands, he could make out the dark figures of men running, perhaps half a dozen in all, and the sleeker, four-legged, shapes moving swiftly across the uneven ground before them.

Another urgent cry went up and Sark knew that they had probably seen his fleeing form outlined against the sky. He ducked down, knowing it was far too late to do any good. He drew the pistol from his belt.

Then the ground gave way and he was falling.

As his feet shot from beneath him, he managed to twist his body and discovered that he had almost reached his destination. It was the edge of the river bank that had collapsed beneath his weight. He barely had time to raise the pistol above his head to avoid mud clogging the barrel, before he landed on his back in the ooze.

He struggled to his knees and pushed himself upright, and then saw the light. It was less than one hundred and fifty yards away, at the edge of the reeds. He strained his eyes. A small building began to take shape and he realized it was the ferry keeper’s cottage. His gaze shifted to the landing stage jutting out into the water; in its lee, a small rowboat resting on the mud and held fast to a thin wooden post. His spirits lifted. There was still a chance he could make it.

With the mud sucking greedily at his boots, Sark struck out for the landing stage. He had gone but a few paces when the consistency of the mud changed. It was less firm now and his boots were sinking deeper with each step. It was like wading through molasses. He looked out at the river. This was one of the narrower stretches, hence the ferry crossing, but the tide was out and there was a wide expanse of foreshore separating the jetty from the water. He would have to drag the boat a good few yards before he could float it. But he could make out the horizontal black shadow that was the opposite shore and that spurred him on. He pushed himself forward.

Behind him, the noises had diminished. There were no more cries, no howling from the dogs. The night was strangely quiet, save for the squelching of Sark’s laborious passage through the mud. Curious, Sark looked around and his blood froze.

They were ranged along the edge of the bank and they were watching him; a line of men, the shadows cast by the torches playing across their unsmiling faces. At their feet, secured by leashes, the hounds stood silently to heel.

The dogs were huge mastiffs, with broad heads and muscular bodies; each one the size of a small calf. As still as statues, they regarded the solitary figure below them with rapt attention. Their only movement was an occasional backward glance at the faces of the men who controlled them.

It was the moment that Sark knew he had nowhere to run.

But it didn’t stop him trying.

Sark estimated he still had about fifty paces to go before he reached the boat. His legs felt as heavy as lead, while the pain behind his ribs suggested his heart was about to burst from his chest. Gamely, he tried to pick up speed but while the spirit was willing, his body was telling him it had reached the point of exhaustion.

Sark did not hear the command to release the dogs, but a sixth sense told him it had been given. He turned. A close observer might have witnessed the look of weary resignation that stole across his face.

The handlers had not followed the hounds down on to the foreshore, but were holding to firmer ground, following the line of the river bank, the flames from their torches flaring like comet trails behind them. They ran in silence.

For the second time that night, Sark dropped to his knees.

The dogs were loping rather than sprinting towards him. With their agility, and their weight distributed between four legs instead of two, making them less susceptible to sinking into the mud, it was as if they knew they had all the time in the world.

All thoughts of escape stifled, Sark gripped the pistol firmly and watched the dogs approach.

He glanced to his side. He saw that the men were now parallel to him, torches raised. They were close enough for him to make out their expressions by the light from the flames. Four of them had faces as hard as rock. The other two were grinning.

Sark’s chest rose and fell. He looked back towards the dogs and raised his pistol. He aimed the barrel at the leading beast and tracked it with the gun’s muzzle.

He heard one of the men on the bank curse and saw that they had all drawn weapons of their own.

Sark could hear the dogs’ paws scampering across the mud. They were coming in very fast; close enough for him to see the light of anticipation in their eyes.

The lead hound was less than a dozen paces away when Sark thrust the barrel of the pistol under his own chin and pulled the trigger.

The back of Sark’s head blew apart. The powder smoke barely had time to dissipate before the still kneeling body was engulfed in a frenzy of snapping jaws and thrashing limbs. As the men on the bank ran towards the mêlée, the snarling of the hounds rose into the night and carried, like the devil’s chorus, down the muddy, bloodstained foreshore.

1 (#ulink_eb78ce96-c992-5f27-9fc2-948e5522b68d)

Outlined against the gunmetal sky, the ship’s blackened hull towered above the men in the longboat like some enormous Hebridean cliff face.

The men were silent, wrapped in their thoughts and awed by the grim sight confronting them. Only occasionally was the silence broken, by the dull clink of manacles, the splash and creak of oars and the wash of the waves against the side of the boat as it was pulled through the cold grey water.

Someone was sobbing. At the sound, several men crossed themselves. Others bowed their heads and, in whispers, began to pray.

There were fifteen men in the boat, excluding the oarsmen and the two marine guards. With few exceptions their clothes were ragged, their faces pale, unshaven and etched with fear; fear caused not only by the ship’s forbidding appearance, but also by the smell coming off her.

It had been with them even before they had embarked, carried across the river by the light easterly breeze. At first, the men had paid little mind, assuming the odour was rising from their own unwashed bodies, but then understanding had dawned. As the longboat had pushed away from the harbour wall they had become transfixed by the grim nature of the fate that was about to befall them. As if to emphasize their passengers’ rising sense of horror, the marine guards traded knowing looks and raised their neck scarves over their lower faces.

The longboat approached the rear of the ship. High above, embedded beneath the stern windows, a nameplate that once had been embossed in gold but which was now tarnished beyond repair proclaimed the vessel to be the Rapacious.

Close to, the ship looked even more intimidating. The dark-hulled vessel had all the appearance of a massive smoke-stained sarcophagus rather than a former ship of the line. There was no mizzen mast and the main mast and the foremast had been cut down to a third of their original size. Only the lower yards remained. Between them, festooned from a web of washing lines running fore and aft, was an array of what, from a distance, might have been taken for signal flags but which, on closer inspection, turned out to be a selection of tattered stockings, shirts and breeches. Age, wear and constant washing had turned every visible scrap of clothing a universal shade of grey, with the majority of the garments exhibiting more holes than material.

These were not the only refurbishments that had been inflicted upon the once proud ship. Her bowsprit had been removed, and where the poop deck had been, there now stood a clinker-built, soot-engrained shack, complete with sloping roof and chimney stack, from which grey smoke was billowing. A similar construction adorned the ship’s forecastle. It was obvious from her appearance that a great many years had passed since Rapacious last experienced the roar and thunder of battle in her search for prey. This was further confirmed by the lack of heavy ordnance; her open gun ports revealed that cannon muzzles had been replaced by immovable cast-iron grilles.

The truncation of her masts and the lack of armament had lightened the ship’s weight considerably. As a result, she was riding much higher out of the water than was normal for a vessel her size. A walkway formed from metal gratings followed the line of the orlop deck. From it a series of wooden stairs rose towards a small platform, similar to a church pulpit, affixed adjacent to the boarding gap in the ship’s handrail.

Huge chains at bow and stern secured Rapacious to the riverbed. Beyond the ship, four more vessels in a similar state of disrepair sat moored in mid-stream, line astern and a cable’s length apart, their blunted bows facing downriver.

All around, a bewildering variety of other vessels lay at anchor, from brigs to cutters and from frigates to flush-decked sloops, their yellow and black hulls gleaming, masts rising tall and straight, while pennants, not grubby pantaloons, fluttered gaily from their yardarms. They were Britain’s pride and they were ready for war.

By comparison, isolated from the rest of the fleet, Rapacious and her four sister ships looked as if they had been discarded and left to rot; victims of a terrible and terminal disease.

Seated in the waist of the longboat, one man ignored the lamentations of his companions and gazed at the ship with what could have been interpreted as interest rather than dread. Two scars were visible on the left side of his face. The first followed the curve of his cheekbone, an inch below his left eye. The second scar, less livid, ran an inch below the first. His long hair was dark save for a few streaks of grey above the temple. His jacket and breeches were severely worn and faded, though in a better state of repair than the clothes of many of the men huddled around him, some of whom were clad in little more than rags. And while the bulk of his companions were either barefooted or else wearing poorly fitting shoes, his feet were shod in what appeared to be a pair of stout but well-scuffed military boots.

“A sou for your thoughts, my friend.”

The words were spoken in French. They came from an aristocratic-looking individual dressed in a dark grey jacket and grubby white breeches, seated on the dark-haired man’s right.

Matthew Hawkwood remained silent but continued staring over the water towards the black-hulled ship.

“Heard she fought at Copenhagen,” the speaker continued in a quiet voice. “She was a seventy-four. They took the idea from us. Extended their seventies. They use them as standard now. Can’t blame the bastards. Good sailing, strong gun-power, what is there not to like?”

The speaker, whose name was Lasseur, grinned suddenly, the expression in marked contrast to the unsmiling faces about him. The neat goatee beard he wore, when added to the grin, lent his features a raffish slant.

The grin disappeared in an instant as a series of plaintive cries sounded from beyond the longboat’s prow.

Ahead, another longboat was tied up against the boarding raft in the shadow of the ship’s grime-encrusted hull. A cluster of men had already disembarked. Huddled on the walkway, under the watchful eyes of armed guards, they were preparing to ascend the stairs. Several of the men had difficulty walking. Two were crawling along the grating on their hands and knees. Their progress was painfully slow. Seeing their plight, their companions lifted them to their feet and with arms about their shoulders shepherded them along.

There were still men left on the first boat. From their posture, it was clear that none of them had the strength to make the transfer on their own. Their cries of distress floated over the water. The two marine guards on the boat were looking up towards the ship’s rail as if waiting for orders, breaking off to jab the barrels and butts of their muskets against the supine bodies around them.

Lasseur bared his teeth in a snarl.

His reaction was echoed by dark mutterings from the men seated about him.

“Silence there!” The order came from one of the marines, who stared at his charges accusingly and brandished his musket, bayonet affixed. “Or so help me, I’ll run you through!” Adding, with ill-disguised contempt, “Frog bastards!”

A face had appeared at the ship’s rail. An arm waved and an inaudible command was given. One of the marines in the boat below responded with a half-hearted salute before turning to his companion and shaking his head. At this the rowers raised their oars and they and the two guards climbed out on to the boarding raft. Turning, one of the rowers used his oar to push the boat away, while one of his fellow boatmen unfastened and began to pay out the line connecting the longboat to the ship. Caught by the current, the longboat moved slowly away from the ship’s hull. When the boat was some thirty or so yards out, the line was retied, leaving the boat’s pitiful passengers to drift at the mercy of the tide.

Angry shouts came from the line of men on the grating. Their protestations were met with a severe clubbing from the guards. Retreating, the quietened men began their slow and laboured ascent of the stairway.

Hawkwood watched grim-faced as the men made their way up the side of the ship. Lasseur followed his gaze and murmured softly, “We’d have been better off with the damned Spanish.”

“Bastards,” a voice interjected bitterly from behind them. “I’ve seen this before.”

Hawkwood and Lasseur turned. The speaker was a thin man, with sunken cheeks and watery eyes. Grey stubble covered his jaw.

“I was in Portsmouth last winter, on the Vengeance. They had a delivery of prisoners transferred from Cadiz. About thirty, all told. As thin as rakes they were; ghost white, not an ounce of flesh on their bones and not so much as a set of breeches between them. Only ten of them made it on to the Vengeance on their own. The rest were too ill to leave the longboat. The Vengeance’s surgeon refused to take them. Ordered them to be delivered to the hospital ship. Only the commander of the Pegasus refused to have them on board, not unless they were washed first. So the Vengeance’s surgeon ordered them thrown into the sea to clean them and left the Pegasus to pick up the bodies. Most of them were dead by the time the Pegasus’s boat got to them.” The man nodded towards the drifting longboat. “Looks to me, that’s what’s happening here.”

“My God,” Lasseur said and fell into a reflective silence as their own longboat, its way now clear, began to manoeuvre towards the ship’s side.

Hawkwood regarded the manacles around his ankles. If the men on the drifting boat, who presumably had also been wearing shackles, had been thrown overboard they would have been beyond help, sinking to the bottom of the river like stones.

He took a look at his fellow passengers. No one returned his gaze. They were too preoccupied, staring up at the ship, craning their necks to take in the vast wooden rampart looming above them. The sense of unease that had enveloped the boat was palpable, as if a black storm cloud had descended. Behind their masks, even the guards looked momentarily subdued.

He could still hear weeping. It was coming from the stern. Hawkwood followed the sound. The boy couldn’t have been much older than ten or eleven. Tears glistened on his cheeks. He looked up, dried his eyes with the heels of his hands and turned away, his small shoulders shaking. His clothes hung in rags about him. He’d been one of a consignment of prisoners, Hawkwood and Lasseur among them, picked up earlier that day from Maidstone Gaol. A midshipman or powder monkey, Hawkwood supposed, or whatever the French equivalent might be, and without doubt the youngest of the longboat’s passengers. It seemed unlikely that the boy had been taken alone, but there didn’t appear to be anyone with him, no shipmates to give him comfort. Hawkwood wondered where the boy had been captured and in what circumstances he might have been separated from the rest of his crew.

The order came to boat oars. A dozen heartbeats later, the longboat was secured to the raft and the transfer began.

The odour from the open gun ports was almost overwhelming. The river was bounded by marshland. On warm days with the wind sifting across the levels, the smell was beyond fœtid, but the malodorous stench issuing from the interior of Rapacious eclipsed even the smell from the shore. It was worse than a convoy of night-soil barges.

Hawkwood shouldered his knapsack. He was one of the few carrying possessions. Most had only the clothes they stood up in.

The marines set about prodding the prisoners with their musket butts. “Goddamn it, move your arses! I won’t tell you again! No wonder you’re losing the bleedin’ war! Useless buggers!”

Legs clanking, the men started to climb from the longboat on to the raft.

“Shift yourselves!” The guards continued to use their weapons to herd the men along the walkway. Movement was difficult due to the shackles, but the guards made no allowance for the restraints. “Lively now! Christ, you buggers stink!”

The insults rained down thick and fast, and while it was doubtful many of the men shuffling along the grating could understand the harsh words, the tone of voice and the poking and prodding made it clear what was required of them.

Slowly, in single file, the men clinked their way up the ship’s side.

“Keep moving, damn your eyes!”

Hawkwood stepped from the stairs on to the pulpit, Lasseur at his shoulder. A jam had formed in the enclosed space. Both men stared down into the belly of the ship. Lasseur recoiled. Then the Frenchman leaned forward so that his mouth was close to Hawkwood’s ear. His face was set in a grimace.

“Welcome to Hell,” he said.

2 (#ulink_2a06dae6-1faf-5b3f-8ed3-945951cdb417)

I should have bloody known, Hawkwood thought.

Ezra Twigg’s face should have given the game away. Hawkwood wondered why he hadn’t picked up the signals. The little clerk’s head had been cast down when Hawkwood entered the ante-room in reply to the Chief Magistrate’s summons. Normally, Twigg would have looked up from his scribbling and passed some pithy comment about the marks on the floor left by Hawkwood’s boot heels, but this time Twigg had barely acknowledged the Runner’s arrival. All he’d done was look up quickly, murmur, “They’re waiting for you,” and return to his paperwork. The omens hadn’t been good. Hawkwood chided himself for not being more observant. Though he had absorbed the warning that the Chief Magistrate had company.

As Hawkwood entered the office, James Read stepped away from the tall window. It was mid-morning and sunlight pierced the room. Hawkwood wondered why the Chief Magistrate, a man who made no secret of his dislike for cold weather, looked so pensive. Given his usual disconsolate manner when confronted with inclement skies, he should, by rights, have been dancing across the carpet.

The second man looked around. He was heavy-set, with short, sandy hair, a broad face and a web of red veins radiating across his cheeks. He was dressed in the uniform of a naval officer and clearly suffered from the habitual stoop, characteristic of so many seamen, which, Hawkwood had come to realize, was more a testimony to the lack of headroom in a man-of-war than any lingering defect of birth.

The officer looked Hawkwood up and down, taking in the scarred face, the unfashionably long hair tied at the nape of the neck and the dark, well-cut attire. The Chief Magistrate walked to his desk. His movements, as ever, were measured and precise. He sat down. “Officer Hawkwood, this gentleman is Captain Elias Ludd. As his uniform implies, Captain Ludd is from the Admiralty.”

Hawkwood and the captain exchanged cautious nods.

“The Transport Board, to be exact,” James Read said.

Hawkwood said nothing. The Transport Board had been created initially to provide ships, troops and supplies during the American War of Independence. But the wars against Bonaparte had seen the Board expand its range of activities far beyond the original borders of the Atlantic. Now, due to Britain’s vast military and naval commitments, the Board was responsible for the movement of supply ships to the four corners of the globe.

“The Admiralty requires our assistance.” Read nodded towards his visitor. “Captain, you have the floor.”

“Thank you, sir.” Ludd looked down at the carpet and then raised his head. “I’ve an officer who’s gone missing; name of Sark. Lieutenant Andrew Sark.”

There was a short silence.

Hawkwood looked towards the Chief Magistrate for guidance, then back to the officer. “And what, you want us to find him? Isn’t that the navy’s job?”

Ludd looked taken aback by Hawkwood’s less than sympathetic response. James Read said, “There are other factors to consider. As you know, the Transport Board’s jurisdiction extends beyond what might be viewed as its traditional bailiwick.”

What the hell did that mean? Hawkwood wondered.

“The Board also administers foreign prisoners of war,” James Read said. “You recall it took over the duty from the Sick and Hurt Board.”

Hawkwood wondered if the Chief Magistrate was expecting a vocal acknowledgement. He decided it was probably best to remain silent. Better to keep your mouth shut and be thought an idiot than to speak and remove all doubt. He decided a noncommittal nod would probably suffice.

“My apologies, Captain,” Read said. “Please continue.”

Ludd cleared his throat. “Over the past several weeks, there’s been a sudden increase in the number of prisoners who’ve escaped from detention. We sent Lieutenant Sark to investigate whether these were random events or part of some orchestrated effort.”

“And he’s failed to report back?” Hawkwood said.

Ludd nodded, his face solemn.

“When did you last hear from him?”

Ludd stuck out his chin. “That’s just it – we haven’t heard from him at all. It’s been six days.”

“Not long,” Hawkwood said.

“In the general scheme of things, I’d not disagree with you.” Ludd gnawed the inside of his lip.

“Captain?” Hawkwood prompted.

Ludd ceased chewing. “He was not the first,” he said heavily.

Hawkwood sensed James Read shift in his seat. Ludd continued to look uncomfortable. “The first officer we sent, a Lieutenant Masterson, died.”

“Died? How?”

“Drowned, it’s presumed. His body was discovered two weeks ago on a mud bank near Fowley Island.”

“Which is where?” Hawkwood asked.

“The Swale River.”

“Kent.”

Ludd nodded. “At the time there was nothing to indicate he’d been the victim of foul play. We mourned him, we buried him, and then Lieutenant Sark was dispatched to continue the investigation.”

“But now that Sark’s failed to report back, you’re thinking that perhaps the drowning wasn’t an accident.”

“There is that possibility, yes.”

“Forgive me, Captain, but I still don’t see what this has to do with Bow Street,” Hawkwood said. “This remains a navy matter, surely?”

Before Ludd could respond, James Read interjected: “Captain Ludd is here at the behest of Magistrate Aaron Graham. Magistrate Graham is the government inspector responsible for the administration of all prisoners of war. He reports directly to the Home Secretary. It was Home Secretary Ryder’s recommendation that the Board avail itself of our services.”

Hawkwood had met Home Secretary Richard Ryder and hadn’t been overly impressed, but then Hawkwood had a low opinion of politicians, irrespective of rank. In short, he didn’t trust them. He had found Ryder to be a supercilious man, too full of his own importance. He wondered if Ryder had been in contact with James Read directly. There was nothing in the Chief Magistrate’s manner to indicate he was talking to Ludd under sufferance, but then Read was a master of the neutral expression. It didn’t mean his mind wasn’t whirring like clockwork underneath the impassive mask.

Read got to his feet. He walked to the fireplace and adopted his customary pose in front of the hearth. The fire was unlit, but Read stood as if warming himself. Hawkwood suspected that the magistrate assumed the stance as a means to help him think, whether a fire was blazing away or not. Oddly, it did seem to imbue an air of gravity to whatever pronouncement he came up with. Hawkwood wondered if that wasn’t the magistrate’s real intention.

Read pursed his lips. “It’s no secret that the Board has come in for a degree of criticism over the past twelve months. It has been the subject of two Select Committees. Their findings were that the Board has not performed as efficiently as expected. Further adverse reports would be most … unhelpful. So far, these escapes have been kept out of the public domain. There’s concern that, should word of its inability to keep captured enemy combatants in check emerge, the government’s credibility could suffer a severe blow. With all due deference to Captain Ludd, while the loss of one officer sent to investigate these escapes might be construed as unfortunate, the loss of two officers could be regarded as carelessness. It is all grist to the mill, and with the nation at war any lack of confidence in the administration could have dire consequences.”

Hawkwood stole a glance at the captain and felt an immediate sympathy. He knew what it was like to lose men in battle; he himself had lost more men than he cared to remember, and it was a painful burden to bear.

“What services?” Hawkwood asked.

Read frowned.

“You said the Home Secretary wants the Board to avail itself of our services. What services?”

James Read looked towards Ludd, who gave a rueful smile. “My superiors are unwilling to commit further resources to the investigation.”

“By resources, you mean men,” Hawkwood said.

Ludd flushed. “As Magistrate Read stated, two officers have apparently fallen prey to the investigation already. I am not anxious to dispatch a third man to investigate the death and disappearance of the first two.”

Everything became clear. Hawkwood stared at James Read. “You want Bow Street to take over the investigation?”

“That is the Home Secretary’s wish, yes.”

“What makes him think we can succeed where the navy has failed?”

Read placed his hands behind his back. “The Home Secretary feels that, while the Admiralty is perfectly capable of assigning officers to the field, there are certain advantages in utilizing non-naval personnel, particularly in what one might consider to be investigations of a clandestine nature.”

“Clandestine?”

“There are avenues open to this office that are not available to other – how shall I put it? – more conventional, less flexible departments of government. Would you not agree, Captain Ludd?”

“I’m sure you’d know more about that, sir,” Ludd said tactfully.

“Indeed.” The Chief Magistrate fixed Hawkwood with a speculative eye.

An itch began to develop along the back of Hawkwood’s neck. It wasn’t a pleasant sensation.

“I refer to the art of subterfuge, Hawkwood; the ability to blend into the background – most useful when dealing with the criminal classes, as you have so ably demonstrated on a number of occasions.”

Hawkwood waited for the axe to fall.

“Captain Ludd and I have discussed the matter. Based on our discussion, I believe you’re the officer best suited to the task.”

“And what task would that be, sir … exactly?”

James Read smiled grimly. “We’re sending you to the hulks.”

The Chief Magistrate’s expression was stern. “We’ve got prisoners of war spread right around the country, from Somerset to Edinburgh. Fortunately for us, the new prison in Maidstone is ideally situated for our purposes. It’s been used as a holding pen for prisoners prior to their transfer to the Medway and Thames hulks. You’ll begin your sentence there. From Maidstone you’ll be transported to the prison ship Rapacious. She’s lying off Sheerness. Better you arrive on the hulk within a consignment of prisoners rather than alone. There’s no reason to suppose anyone will question your credentials, but it should give you an opportunity to form liaisons with some of your fellow internees before embarkation.”

It was interesting, Hawkwood mused, that the Chief Magistrate had used the word sentence rather than assignment. Perhaps it had been a slip of the tongue. Then again, he thought, maybe not.

“Your mission is several fold,” Read said. “Firstly, you are to investigate how these escapes have been achieved –”

“You mean you don’t know?” Hawkwood cut in, staring at Ludd.

Ludd shifted uncomfortably. “We know Rapacious has lost four prisoners in the past six weeks. The trouble is, we don’t know the exact time the losses took place. We can assume the other prisoners concealed the escapes from the ship’s crew, possibly by manipulating the roll count. Without knowing the precise times of the escapes we haven’t been able to pin down how they were achieved, whether it was a spur-of-the-moment thing based on a lapse in our procedures or if the escapes were planned and executed over a period of time. All we know is that Rapacious is missing four men. What makes it more interesting is that there have been similar losses from some of the other Medway-based ships. We’re also missing a couple who broke their paroles.”

“How many in total?” Hawkwood asked.

“Ten unaccounted for.”

“Over how long a period?”

“Two months,” Ludd said.

“As I was saying …” James Read spoke into the pregnant silence which followed Ludd’s admission. “You are also to determine whether the escapers have received outside assistance. Captain Ludd is of the opinion that they have.”

“Based on what?” Hawkwood said.

“Based on the fact that we haven’t managed to track any of the buggers down,” Ludd said.

“Explain.”

Ludd sighed. “Escapes are nothing new. Some are spontaneous; the sudden recognition of an opportunity presenting itself: a door left unlocked, a careless guard looking the other way during a working party, that sort of thing. They generally involve a prisoner acting on his own. Nine times out of ten, he’s rounded up quickly, usually because he’s cold and wet and he can’t find food or clothing, he’s no idea where he is and he daren’t ask directions because he can’t speak the language. They don’t last long. Many end up turning themselves in voluntarily – and not just to the military. They’ve even surrendered to people in the street. But when it’s more than one, when two or three at a time have made a run for it, that suggests they’ve devised a plan, hoarded food and spare clothing, maybe bribed a guard to sell them a map so they know how far it is to the coast, and where they can steal a boat. Even so, not many make it. All it takes is one careless word; someone overhears them speaking Frog or talking English with an accent and the game’s up. But these recent escapes, they’ve been different.”

“How so?”

“As I said, we weren’t able to pick up their trail.”

“Which means what?”

“In my book, it means someone’s definitely helping them.”

“Like who?”

“That’s what we sent Masterson and Sark to find out.”

“What do you think?”

“My own theory? Free traders, most likely.”

“Smugglers?”

“My guess is that they’re passing the escapers down the line to the coast. They’ve got the routes all set up, they’ve got the men and the boats.”

“That, Hawkwood, is the third part of your assignment,” Read said. “If there is an organized escape route, I want it disrupted, preferably disbanded.”

“It might explain why your Lieutenant Masterson was found in the Swale,” Hawkwood said. “Could be he was thrown from a vessel.”

“Could be,” Ludd agreed. “I’d deem it a personal favour if, along the way, you could find out what happened to my men. If they were done away with, I’d prefer to be told.”

“If free traders are involved, it won’t be easy,” Hawkwood pointed out. “They’re a law unto themselves. Anyone going in and asking questions is sure to make their ears prick up. It’s more than likely they’ll see me coming a mile away.”

Ludd and Read exchanged glances.

“Quite so,” James Read said quietly. “But in this case they’re going to be looking in the wrong direction.”

“Hindsight’s a wonderful thing,” Ludd said. “Our mistake was sending Masterson and Sark through the front door. They were competent men, but they were naval officers first and landsmen second. In this situation they were out of their depth, no pun intended. We might just as well have dispatched a marching band to accompany them. Masterson’s brief was to try and infiltrate the smuggling organizations. We thought the best way for him to do that was to have him pose as a former seaman looking for work and to make it clear he wasn’t too bothered whether the work was legal or not. Trouble is, the smuggling fraternity’s too closely knit. My feeling is he ended up asking the wrong people the wrong questions – and that Sark made the same mistake.”

“You can take the man out of the navy but you can’t take the navy out of the man,” Hawkwood said.

“Something like that,” Ludd agreed unhappily.

“You, on the other hand, will not be quite so obvious,” James Read said. “We hope.”

“You mean I’ll be using the tradesman’s entrance,” Hawkwood said.

The corner of Read’s mouth twitched. “Providing we can manufacture a suitable history for you.” The Chief Magistrate paused. “My initial thought was that you should pass yourself off as a French officer, but I’m not sure that’s entirely practical. While I appreciate that your knowledge of the language is considerable, could you maintain the deception for any length of time? Captain Ludd and I have discussed the matter and we believe the current crisis with the United States has provided us with the perfect solution. You will pass yourself off as an American volunteer.”

“An American?”

“As you know all too well, from your recent encounter with William Lee, our American cousins are less than enamoured with us of late. Even before the recent declaration of war, a substantial number of American citizens have been drawn to Bonaparte’s flag; a legacy of American and French liaison during the Revolutionary War. With that in mind, we thought you could assume the mantle of an American officer attached to one of Bonaparte’s regiments who has been captured in the field. The fact that you are conversant in French gives us a distinct advantage.

“All that remains is your identity. Something credible that will pass scrutiny, preferably based on your own expertise and, ideally, involving an engagement of which you have personal knowledge. The only problem with that, however, would be the question of your whereabouts over the past three years. The most logical choice would therefore seem to be something more recent, from which all the facts have yet to be sifted. Captain Ludd and I have perused dispatches and determined that the victory at Ciudad Rodrigo will best fit the bill. Reports of the battle are still being disseminated. Are you familiar with any of the details?”

“Only from what I’ve read in the news sheets,” Hawkwood said.

The Times had carried general reports of the battle, as had the Chronicle and the Gazette. Ciudad Rodrigo was a picturesque Spanish town overlooking the Agueda River. Only a few miles from the border, it guarded the main northern route between Spain and Portugal. Wellington had laid siege to the town at the beginning of January. The attack had been a ferocious affair. Casualties had been heavy, but Wellington had emerged victorious. Many prisoners had been taken.

Read nodded. “Very good; a volunteer captain attached to the 34th Régiment d’Infanterie Légère will be the most fitting for our purposes, I venture. The regiment was created last year, drawing men from other units, so there is every possibility they could have utilized foreign experts in the field. I’ll leave you to manufacture an appropriate biography for yourself.”

The Chief Magistrate reached across his desk and picked up a small canvas pouch. “These are some of the reports pertaining to the siege. Make use of them. They contain details that are not public knowledge; for obvious reasons, as you’ll discover. Our own soldiers may well have emerged victorious, but they did not cover themselves in glory. Such knowledge could assist in fending off awkward questions. Use it to your advantage if you find yourself pressed. Attack is the best form of defence. Denigrating your former comrades in arms will help deflect attention from your alias. Read the dispatches. You’ll see what I mean.”

Read handed over the pouch. “As an officer, you’ll be permitted to carry a few personal belongings. Mr Twigg will provide you with funds. French and British currency is used on the hulks. I would urge you to be circumspect in your expenditure, however. The coffers of the Public Office are not a bottomless pit.

“The wounds you received in the Hyde case will stand you in good stead. They’re recent enough to have been sustained around the supposed date of your defeat and capture. They will add to your credibility.”

The scars from his encounter with the escaped Bedlamite, Titus Hyde, had healed well. But that wasn’t to say he didn’t sometimes wake in the small hours wondering what might have become of him had the blade of Hyde’s sword been an inch longer. The razor-thin weal along the rim of his left cheek was a visible reminder that the line between life and death can be measured by the breadth of a single hair or the span of a heartbeat.

“Who else will know I’m a peace officer?”

Read hesitated before replying. “No one. Aside from myself, Captain Ludd and Mr Twigg, no one else will be privy to your true identity.”

“Not the hulk’s commanding officer?”

“No one,” Read repeated.

“So, how do I send word if I discover something?”

“That’s why you’ll be listed as an officer in the ship’s register. It entitles you to apply for parole. Captain Ludd recommends we make it appear as though your application is pending authorization. You will thus be required to appear before a board of assessment. Your first interview will be scheduled to take place one week after your arrival. Captain Ludd will be the officer in charge. You will provide him with details of any progress you may have made.”

Hawkwood stared at the dispatch pouch and then looked up. “In that case, I hope you all remain in good health. I’d hate to find I’m stranded on the bloody ship because you’ve all been struck dead in your beds.”

3 (#ulink_47f7f00a-ae1e-5142-b1ee-a1c8900729d1)

“Name?”

The question was emitted in a thin, reedy voice by a narrow-shouldered, sour-faced man seated behind a large trestle table that had been set up in the forward section of the weather-deck. The clerk did not look up but waited, lips compressed, pen poised, for Hawkwood to reply. A large ledger lay open in front of him. The seated man to his right, a supercilious-looking individual with reddish-blond hair, slim sideburns and nails bitten down to the quick, wore a lieutenant’s uniform. The one standing by his left shoulder was younger, slightly built, dark haired, and dressed in a yellow canvas jacket and matching trousers. Stamped on the sleeves of the jacket and upon each trouser leg were a broad black arrow and the letters T.O., the initials of the Transport Office. His eyes roved back and forth along the line of waiting men.

Hawkwood gazed down at the clerk and said nothing. He was still feeling the chill from the dousing he had received.

The guards had removed the shackles and made all the new arrivals strip naked on deck before handing them a block of brown soap and ordering them into large water-filled barrels. The water was freezing and by the time each man had rubbed himself raw, clambered out, passed the soap on to the next man and dried himself with the rag towel, the water surface in every tub was covered by a thin oily residue.

Orange jackets, trousers and shirts had then been distributed. There seemed to be only one size, small, which left the recipients struggling woefully to fasten the jacket buttons. With most, the trousers reached only as far as mid calf. The only person to emerge from the handout with any modicum of dignity was the boy from the longboat. The jacket was too long at both hem and sleeve, but the trousers were close to being a good fit, albeit only after they had been secured around the boy’s thin waist by a length of twine.

Not everyone received a uniform. A number of men, Hawkwood and Lasseur among them, were allowed to keep their own clothes, supposedly because they were officers, though Hawkwood suspected it had more to do with a scarcity of jackets and trousers rather than an acknowledgement of their rank. Certainly, it appeared that prison uniform had been passed, in the main, to those whose own apparel was beyond salvage. All soiled articles were tossed on to a growing pile on the deck. To be taken off the ship, Hawkwood assumed, and burned.

Next, canvas slippers were distributed. Neither Hawkwood nor Lasseur were deemed impoverished enough to warrant the gift of the shoes. Hawkwood noticed that both his and Lasseur’s footwear were attracting surreptitious attention from some of the less fortunate prisoners and he made a silent vow not to let his boots out of his sight.

A look of irritation moved across the registration clerk’s pinched face at Hawkwood’s lack of response. The lieutenant maintained his impression of boredom. The clerk flicked his finger imperiously and the man standing at his shoulder in the yellow uniform repeated the question in French.

“Hooper,” Hawkwood said. “Matthew.”

As Hawkwood gave his name, the clerk stiffened and frowned, while next to him the lieutenant’s head snapped round. His eyes darkened.

The clerk recovered his composure and turned his eyes to the grainy sheet of paper at his elbow. He ran the nib of his pen down the page and gave a small click of his tongue as he found the entry he was looking for. Hawkwood assumed it was the list of prisoners transferred from Maidstone and that the clerk was confirming his name.

The lieutenant peered over the clerk’s shoulder.

The clerk sneered. “Our first American. Not so independent now, are you?” He sniggered at his own wit.

The lieutenant viewed Hawkwood with undisguised hostility as the clerk began to transfer the details into the ledger, repeating the information under his breath as he did so. “Rank: captain; date of capture: 20th January; action in which taken: Ciudad Rodrigo; date of arrival: 27th May; application for parole under consideration; physical description …” The clerk raised his eyes again and murmured, “Height: approximately six feet; scarring on left side of face … surly-looking brute. Assigned to the gun deck. Next!”

After listening silently to the description and the comment, the lieutenant favoured Hawkwood with a final grimace of distaste before he turned away.

“Damned renegade,” Hawkwood heard him mutter under his breath.

The interpreter jerked his head for Hawkwood to move along. Behind him, he heard Lasseur give his name and the clerk’s litany began again.

At the next table the prisoners were presented with a rolled hammock, a threadbare blanket and a thin, wool-stuffed mattress.

Hawkwood studied the armed guards ringing the deck. Their escort had been composed of marines, seconded to the shore establishment, but neither the army nor the navy liked to assign regulars to the prison ships. True fighting men were needed abroad. This lot would be members of a local militia, specially recruited, Ludd had told him. He’d seen two of the guards exchange knowing grins as they stared at the boy’s milk-white buttocks during the enforced bathing. One of them had nudged the other and sniggered. “Wait till His Majesty gets a look at that!”

Hawkwood wondered what that meant.

The processing stretched over two hours. There were not that many new arrivals – three boatloads in all, perhaps forty men in total – but the ill-tempered admissions clerk seemed intent on proving how pedantic he could be. Slowly, however, the line of men began to shorten. Hawkwood was intrigued as to why they’d been herded into one half of the quarterdeck rather than escorted below. His question was answered as the last prisoner was handed his bedding.

A figure appeared at the rail of the deck above them. He was tall and raw-boned. His face was gaunt and pale. The white piping on his lapels proclaimed him to be another lieutenant, though he looked old to be holding the rank. Hands clasped behind his back, he gazed dispassionately at the crowd of men gathered beneath him. His eyes were very dark. Gradually, as the prisoners became aware that they were being observed, an uneasy silence descended upon the deck. Beneath his hat, the lieutenant’s eyes moved unblinkingly over the upturned faces. The clerk and the lieutenant at the table rose to their feet.

The gaunt lieutenant remained by the rail, his body incredibly still, as he continued to stare down. Not a word was uttered. Only the sound of the gulls wheeling high above the ship broke the stillness. Then, abruptly, after what seemed like minutes but could only have been twenty or thirty seconds, the lieutenant stepped back from the rail, turned abruptly, and, still not having spoken, returned from whence he came.

“Our brave commander,” Lasseur whispered. “Rumour has it he once captained a frigate, had a run-in with one of our eighties off Finisterre, and surrendered his ship. After they exchanged him, he was court-martialled.” Lasseur sucked in his cheeks. “Took to drink, I’m told.”

Hawkwood wondered where Lasseur had got his information. Some people had an uncanny knack of picking up all kinds of rumours. Though, in fact, Lasseur was only half right. The commander of the hulk, if that’s who the lieutenant had been, was named Hellard and he had indeed been demoted from captain. But it had been Funchal not Finisterre where the lieutenant’s fate had been sealed, and he had taken refuge in the bottle before the engagement, not following it. Hawkwood had been told the correct version by Ludd during his briefing; though it didn’t alter the fact that Hellard had been assigned to Rapacious as punishment. Furthermore Ludd had told Hawkwood that Hellard’s background was modest, which meant he’d been unable to call on a patron to rescue him from exile and set him back on the promotion ladder. Commanding this floating tomb was as high as Lieutenant Mortimer Hellard was ever going to get. And he knew it. It accounted for the stony countenance, Hawkwood thought. This was a man resigned to his fate, resenting it, and suffering because of it.

“Take them below, Sergeant Hook.” The order came from the lieutenant with the bitten fingernails. “And do something about those. They’re making the place look untidy.”

The lieutenant scowled at a pair of prisoners whose legs had given way. Hawkwood assumed they were the two who had been helped up the stairs by their fellow detainees. He wondered what had become of the men who’d been left in the longboat, and whether anyone had bothered to retrieve them. No one in authority on Rapacious seemed interested in taking a look. It was more than likely the boat was still drifting at the end of the line.

“Aye, sir.” The sergeant of the guard saluted lazily and turned to the prisoners. He nodded towards the stairway. “Right, you buggers, let’s be having you. Simmons, use your bayonet! Give that one at the back there a poke. Get the bastards moving! We ain’t got all bleedin’ day! Allez!”

Lasseur caught Hawkwood’s eye. The Frenchman’s smile had slipped from his face. It was as if the reality of the situation had finally sunk in. Hawkwood shouldered his bedding, remembering Lasseur’s earlier whispered comment. As he descended the stairs to the well deck it didn’t take him long to see that Lasseur had been mistaken. Hell would have been an improvement.

Hawkwood was no stranger to deprivation. It was all around him on London’s cramped and filthy streets. In the rookeries, like those of St Giles and Field Lane, poverty was a way of life. It could be seen in the way people dressed, in the looks on their faces and by the way they carried themselves. Hawkwood had also seen it in the eyes of soldiers, most notably in the aftermath of a defeat, and he was seeing the same despair and desperation now, carved into the faces of the men gathered on the deck of the prison hulk. It was the grey, lifeless expression of men who had lost all hope.

They ranged in age from calloused veterans to callow-eyed adolescents and they looked, with few exceptions Hawkwood thought, like the ranks of the walking dead. Most wore the yellow uniform, or what was left of it, for in many cases the prison garb looked to be as ragged as the clothing that had been stripped from the backs of the new arrivals. Many of the older men had the weathered look of seamen, though without the ruddy complexion. Instead, their faces were pallid, almost drained of colour.

Some prisoners huddled in small groups, others stood alone, if such a feat was possible given the number of wasted bodies that seemed to cover every available inch of space. Some of the men were stretched out on the deck, but whether they were sleeping or suffering from some malady, it was impossible to tell. The ones that remained upright gazed dully at the new arrivals being directed towards the hatch and the stairs leading into the bowels of the ship. Some of the men looked as though they hadn’t eaten for days.

“My God,” Lasseur gagged. “The smell.”

“Wait till you get below.”

The voice came from behind them. Hawkwood looked back over his shoulder and found himself eye to eye with the dark-haired interpreter from the weather-deck.

“Don’t worry; in a couple of days, you won’t notice. In a week, you’ll start to smell the same. The name’s Murat, by the way. And we call this area the Park. It’s our little joke.” The interpreter nodded towards the open hatch and the top of the ladder leading down. “You’d best get a move on. Squeeze through, find yourselves a space.”

“Murat?” Lasseur looked intrigued. “Any relation?”

The interpreter shrugged and gave a self-deprecatory grin. “A distant cousin on my mother’s side. I regret our closest association is in having once enjoyed the services of the same tailor. I –”

“How much do you want for your boots?”

Hawkwood felt a tug at his sleeve. One of the yellow-uniformed prisoners had taken hold of his arm. Hawkwood recoiled from the man’s rancid odour. “They’re not for sale.”

There were ragged holes in the elbows of the prisoner’s jacket and the knees of his trousers shone as if they had been newly waxed. His feet were stuffed into a pair of canvas slippers, though they were obviously too small for him as his heels overlapped the soles by at least an inch. Several boils had erupted across the back of his neck. His shirt collar was the colour of dried mud.

“Ten francs.” The grip on Hawkwood’s arm tightened.

Hawkwood looked down at the man’s fingers. “Let go or you’ll lose the arm.”

“Twenty.”

“Leave him be, Chavasse! He told you they’re not for sale.” Murat raised his hand. “In any case, they’re worth ten times that. Go and pester someone else.”

Hawkwood pulled his arm free. The prisoner backed away.

The interpreter turned to Hawkwood. “Keep hold of your belongings until you know your way around, otherwise you might not see them again. Come on, I’ll show you where to go.”

Murat pushed his way ahead of them and started down the almost vertical stairway. Hawkwood and Lasseur followed him. It was like descending into a poorly lit mineshaft. Three-quarters of the way down Hawkwood found he had to lean backwards to avoid cracking his skull on the overhead beam. He felt his spine groan as he did so. He heard Lasseur chuckle. The sound seemed ludicrously out of place.

“You’ll get used to that, too,” Murat said drily.

Hawkwood couldn’t see a thing. The sudden shift from daylight to near Stygian darkness was abrupt and alarming. If Murat hadn’t been wearing his yellow jacket, it would have been almost impossible to follow him in the dark. It was as if the sun had been snuffed out. Hawkwood paused and waited for his eyes to adjust.

“Keep moving!” The order came from behind.

“That way,” Murat said, and pointed. “And watch your head.”

The warning was unnecessary. Hawkwood’s neck was already cricked. The height from the deck to the underside of the main beams couldn’t have been much more than five and a half feet.

Murat said, “It’s easy to tell you’re a soldier not a seaman, Captain. You don’t have the gait, but, like I said, you’ll get used to it.”

Ahead of him, Hawkwood could see vague, hump-backed shapes moving. They looked more troglodyte than human. And the smell was far worse down below; a mixture of sweat and piss. Hawkwood tried breathing through his mouth but discovered it didn’t make a great deal of difference. He moved forward cautiously. Gradually, the ill-defined creatures began to take on form. He could pick out squares of light on either side, too, and recognized it as daylight filtering in through the grilles in the open ports.

“This is it,” Murat said. “The gun deck.”

God in heaven, Hawkwood thought.

He could tell by the grey, watery light the deck was about forty feet in width. As to the length, he could only hazard a guess, for he could barely make out the ends. Both fore and aft, they simply disappeared into the blackness. It was more like being in a cellar than a ship’s hull. The area in which they were standing was too far from the grilles for the sunlight to penetrate fully but he could just see that benches ran down the middle as well as along the sides. All of them looked to be occupied. Most of the floor was taken up by bodies as well. Despite the lack of illumination, several of the men were engaged in labour. Some were knitting, others were fashioning hats out of what looked like lengths of straw. A number were carving shanks of bone into small figurines that Hawkwood guessed were probably chess pieces. He wondered how anyone could see what they were doing. The sense of claustrophobia was almost overpowering.

He saw there were lanterns strung on hooks along the bulkhead, but they were unlit.

“We try and conserve the candles,” Murat explained. “Besides, they don’t burn too well down here; too many bodies, not enough air.”

For a moment, Hawkwood thought the interpreter was joking, but then he saw that Murat was serious.

There was just sufficient light for Hawkwood to locate the hooks and cleats in the beams from which to hang the hammocks. Many of the hooks had objects suspended from them; not hammocks but sacks, and items of clothing. They looked like huge seedpods hanging down.

Murat followed his gaze. “The long-termers get used to a particular spot. They mark their territory. You can take any hook that’s free. Hammocks are slung above and below, so there’ll be room for both of you. Best thing is for you to put yours up now. The rest are on the foredeck; they’re taken up there every morning and stowed. When they’re brought back down you won’t be able to move. You’ve got about six feet each. Come night time there are more than four hundred of us crammed in here. You’re new so you don’t get to pick. When you’ve been here a while you might get a permanent place by the grilles.”

“How long have you been here?” Hawkwood asked.

“Two years.”

“And how close are you to the grilles?”

Murat smiled.

“What if we want a place by the grilles now?” Lasseur said. His meaning was clear.

Four hundred? Hawkwood thought.

“It’ll cost you,” Murat said, without a pause. He read Hawkwood’s mind. “Think yourself lucky. You could have been assigned the orlop. There are four hundred and fifty of them down there, and it isn’t half as roomy as this.”

“How much?” Lasseur asked.

“For two louis, I can get you space by the gun ports. For ten, I can get you a bunk in the commander’s cabin.”

“Just the gun port,” Lasseur said. “Maybe I’ll talk to the commander later.”

Murat squinted at Hawkwood. “What about you?”

“How much in English money?”

“Cost you two pounds.” The interpreter eyed them both. “Cash, not credit.”

Hawkwood nodded.

“Wait here,” Murat said, and he was gone.

Lasseur stared around him. “I boarded a slaver once, off Mauritius. It turned my stomach. This might be worse.”

Hawkwood was quite prepared to believe him.

Lasseur was the captain of a privateer. The French had used privateers for centuries. Financed by private enterprise, they’d been one of the few ways Bonaparte had been able to counteract the restrictions placed upon him by the British blockade. But their numbers had declined considerably over the past few years due to Britain’s increased dominance of the waves in the aftermath of Trafalgar.

Getting close to Lasseur had been Ludd’s idea, though the initial strategy had been Hawkwood’s.

“I need an edge,” he’d told James Read and Ludd. “I go in there asking awkward questions from the start and I’m going to end up like your man Masterson. The way to avoid that is to hide in someone else’s shadow. I need to make an alliance with a genuine prisoner, someone who’ll do the running for me so that I can slip in on his coat-tails. You said you’re sending me to Maidstone. Find me someone there I can use.”

Ludd had met with Hawkwood the day prior to his arrival at the gaol.

“I think I have your man,” Ludd told him. “Name of Lasseur. He was taken following a skirmish with a British patrol off the Cap Gris-Nez. The impudent bugger tried to jump ship twice following his capture; even had the temerity to make a dash for freedom during his transfer from Ramsgate. If anyone’s going to be looking for an escape route, it’ll be Lasseur; you can count on it. He’s made a boast that no English prison will be able to hold him. Get close to him and my guess is you’re halfway home already.”

The introduction had been manufactured in the prison yard.

Lasseur had been by himself, back against the wall, enjoying the morning sun, an unlit cheroot clamped between his teeth, when the two guards made their move. The plan would never have been awarded marks for subtlety. One guard snatched the cheroot from between Lasseur’s lips. When the Frenchman protested, the second guard slammed his baton into Lasseur’s belly and a knee into his groin. As Lasseur dropped to the ground, covering his head, the guards waded in with their boots.

A cry of anger went up from the other prisoners, but it was Hawkwood who got there first. He pulled the first guard off Lasseur by his belt and the scruff of his neck. As his companion was hauled back, the second guard turned, baton raised, and Hawkwood slammed the heel of his boot against the guard’s exposed knee. He pulled his kick at the moment of contact, but the strike was still hard enough to make the guard reel away with a howl of pain.

By this time, the first guard had recovered his balance. With a snarl, he swung his baton towards Hawkwood’s head. But the guard had forgotten Lasseur. The privateer was back on his feet. As the baton looped through the air, Lasseur caught the guard’s wrist, twisted the baton out of his grip, and slammed an elbow into the guard’s belly.

Shouts rang out as other guards, wrongfooted by the swiftness of Hawkwood’s intervention, came running. It had taken four of them to subdue Hawkwood and Lasseur and march them off into a cell.

The clang of the door and the rasp of the key turning in the lock had seemed as final as a coffin lid closing.

Lasseur’s first action as soon as the door shut was to take another cheroot from his jacket, put it between his lips and ask Hawkwood if he had a means by which to light it. Hawkwood had been unable to assist. Whereupon Lasseur had shrugged philosophically, placed the cheroot back in his jacket, extended his hand and said, “Captain Paul Lasseur, at your service.” Then he’d grinned and touched his ribs tentatively. “I suppose it was one way of getting a cell to ourselves.”

Hawkwood hadn’t thought it would be that easy.

Lasseur had managed to maintain the devil-may-care façade up to the moment he’d seen the men in the longboat being cast adrift from the hulk’s side.

Around them, the other fresh arrivals assigned to the gun deck were also looking for places to bed down. The invasion of their living quarters had caused most of the established prisoners to pause in their tasks to take stock of the new blood. The mood, however, seemed strangely subdued. Hawkwood wondered if the original prisoners resented this further reduction of what was already a barely adequate living space.

Among the new batch was the boy. He was standing alone, weighed down by his hammock, mattress and blanket, utterly bewildered by the activity going on around him; though he was one of the lucky ones in as much as he did not have to amend his posture in order to move about inside the hull. He looked like a small boat tossed by waves as he was turned this way and that by the men brushing past him, mindless of his size.

The boy turned. One of the other prisoners, a slight, weak-chinned, effete-looking man with a widow’s peak of thinning hair – a long-standing resident of the hulk if the decrepit state of his yellow uniform was any indication – was crouched down with his right hand on the boy’s shoulder.

Hawkwood watched as a look of doubt crept over the boy’s face. The boy shook his head. The man spoke again, his expression solicitous. The boy tried to squirm away from the man’s touch, but the latter took hold of his jacket sleeve. The hand on the boy’s shoulder slid down and began to make gentle circular movements in the small of the boy’s back. The boy looked petrified. Hawkwood took a step forward.

“No,” Lasseur said softly, “I’ll deal with it.”

Hawkwood watched as Lasseur ducked beneath the beams and the hanging sacks. He saw the privateer place his hand on the man’s shoulder, lean in close and speak softly into his ear. The man said something back. Lasseur spoke again and the man’s smile slipped. Then he was holding his hands up and backing away. Lasseur did not touch the boy but squatted down and spoke to him.

A voice in Hawkwood’s ear said, “Right, it’s all arranged; a room with a view for both of you.” Murat looked around. “Where’s your friend?”

“Here,” Lasseur said. He was standing behind them. The boy stood at his side, clutching his bedding. “This is Lucien. Lucien, say hello to Captain Hooper and our interpreter, Lieutenant … my apologies, I didn’t catch your given name.”

“Auguste,” Murat said.

“Lieutenant Auguste Murat,” Lasseur finished. He fixed Murat with an uncompromising eye. “I want space for the boy as well.”

Murat’s eyebrows rose. He shook his head. “I regret that’s not possible.”

“Make it possible,” Lasseur said.

“There’s no room, Captain,” Murat protested.

“There’s always room,” Lasseur said.

Murat looked momentarily taken aback by Lasseur’s abrasive tone. He stared down at the boy, took in the small, pale features and then threw Lasseur a calculating look. “It could be expensive.”

“You do surprise me,” Lasseur said.

Murat’s brow wrinkled, unsure how to respond to Lasseur’s barb, before it occurred to him it was probably best to tell them to wait once more and that he would return.

Hawkwood and Lasseur watched him go.

“I have a son,” Lasseur said. He did not elaborate but looked down. “How old are you, boy?”

The boy gripped his bedding. In a wavering voice, he said, “Ten, sir.”

“Are you now? Well, stick with us and you might just make it to eleven.”

Murat reappeared and, unsmiling, crooked a finger. “Come with me.”

Stepping around and over bodies, heads bent, the two men and the boy followed the interpreter towards the starboard side of the deck.

“You’re in luck –” Murat spoke over his shoulder “– another place has become vacant. The former owner doesn’t need it any more.”

“That’s fortunate,” Lasseur said. He caught Hawkwood’s eye and winked. “And why’s that?”

“He died.”

Lasseur halted in his tracks.

Murat held up his hands. “Natural causes, Captain, on my mother’s life.”

Lasseur looked sceptical.

“From the fever. They say it’s due to the air coming off the marshes.” Murat jabbed a thumb towards the open grilles. “It’s the same both sides of the river. It’s what most men die of, that and consumption. That’s the way it happens on the hulks. You rot from the inside out.”

Hawkwood noticed that the prisoners near the gun ports were making use of the light to read or write, using the bench along the side of the hull as a makeshift table. Some were conversing with their companions while they wrote. As he passed, Hawkwood realized they were conducting classes. He looked over a hunched shoulder and guessed by the illustrations and indecipherable script that the subject was probably mathematics.

“It’s best to try and keep busy,” Murat said, interrupting Hawkwood’s observations. “You’ll lose your mind, otherwise. Many men have.” The lieutenant pointed. “Here you are, gentlemen. Welcome to your new home.”

Compared to where they’d just come from, it was the height of luxury. Hawkwood wondered how Murat had persuaded the previous incumbents to relinquish such a valuable location. It didn’t seem possible that anyone would want to do so voluntarily. Maybe they were dead, too.

They weren’t, Murat assured them. “It’s just that they prefer food to a view. You’d feel that way, too, if you hadn’t had a square meal for a week,” Murat added, pocketing his fee. “You’ll learn that soon enough. If I were you, I’d guard my purse. Don’t indulge in fripperies. The price you’ve just paid for your sleeping spot will buy three weeks’ rations. Not that they give us anything worth eating, mind you. There are some who’d say death from the fever would be a merciful release. If you want to make a bit of money, by the way, you can rent out your part of the bench.”

“I knew I could count on you,” Lasseur said. “I had this feeling in my bones.”

The interpreter permitted himself a small smile. His teeth were surprisingly even, though in the gloom they were the colour of damp parchment. “Thank you, Captain. And might I say it’s been a pleasure doing business with you.”

Murat turned. “And the same goes for you, Captain Hooper. It’s a pleasure to meet an American. I’ve long been an admirer of your country. Now, if there’s anything else you require, don’t hesitate to ask. You’ll find I’m the man to do business with. You want to buy, come to Murat. You have something to sell, come to Murat. My terms are very favourable, as you’ll see.”

“You’re a credit to free enterprise, Lieutenant,” Lasseur said.

Murat volunteered a full-blown conspiratorial grin. “You’re going to fit right in here, Captain.” The interpreter gave a mock salute. “Now, if you’ll excuse me, gentlemen.” And with that, he turned on his heel, and walked off. To hand the money on, Hawkwood assumed, minus his commission, of course.

“I do believe we’ve just been robbed,” Lasseur said cheerfully, and then shrugged. “But it was neatly done. I can see we’re going to have to keep our eyes on Lieutenant Murat. Did you ever have any dealings with his cousin?”

Hawkwood shook his head and said wryly, “Can’t say I’m likely to, either, considering I’m an American and he’s the King of Naples.”

“I keep forgetting: your French is very good. Murat’s cousin served in Spain, though.”

“I know,” Hawkwood said. “And your army has been trying to clean up his damned mess ever since.”

Lasseur looked taken aback by Hawkwood’s rejoinder. Then he nodded in understanding. “Ah, yes, the uprising.”

It had been back in ’08. In response to Bonaparte’s kidnapping of the Spanish royal family in an attempt to make Spain a French satellite, the Spanish had attacked the French garrison in Madrid. Retaliation, by troops under the command of the flamboyant Joachim Murat, had been swift and brutal and had led to a nationwide insurrection against the invaders, which had continued, with the assistance of the British, ever since.

Lasseur gave a sigh. “Kings and generals have much to answer for.”

“Presidents and emperors, too,” Hawkwood said.

Lasseur chuckled.

The boy moved to the port and stared through the grille.

Hawkwood did the same. Over the boy’s shoulder he could see ships floating at anchor and beyond them the flat, featureless shoreline and, further off, some anonymous buildings with blue-grey rooftops. He heard the steady tread of boot heel on metal. He’d forgotten the walkway. It was just outside the scuttles. He waited until the guard’s shadow had passed then gripped the grille and tried to shake it. There was no movement. The crossbars were two inches thick and rock solid.

“Well, I doubt we’ll be able to cut our way out,” Lasseur said, running an exploratory hand over the metal.

“Planning on making a run for it?” Hawkwood asked.

“Why do you think I would never ask for parole?” Lasseur said. “You wouldn’t want me to break my word, would you?” The Frenchman grinned and, for a moment, there was a flash of the man who had arrived in the gaol cell at Maidstone looking for a means to light his cheroot. He regarded Hawkwood speculatively.

“I’m still considering my options,” Hawkwood said.

Lasseur smiled.

The irony was that Lasseur wouldn’t have been entitled to parole anyway, even if he hadn’t already proved he was a potential escape risk by virtue of his earlier breaks for freedom.

There were stringent rules governing the granting of parole, which entitled an officer to live outside the prison to which he’d been assigned. It meant securing accommodation in a designated parole town, sometimes taking a room with a local family or, if possessed of sufficient funds, within a lodging house or inn. In return, the officer gave his word he would not break his curfew but would remain within the town limits and make no attempt to escape. The penalty for transgressing, if apprehended, was a swift return to a prison cell.