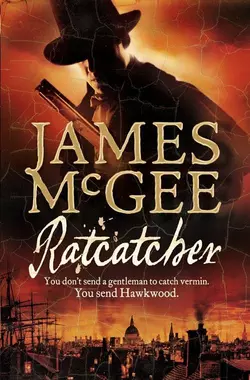

Ratcatcher

James McGee

Regency London is vividly brought to life in this extraordinary page-turner, the first in a series of historical thrillers featuring Bow Street Runner Matthew Hawkwood – a dangerous, sexy and fascinating hero.Hunting down highwaymen was not the usual preserve of a Bow Street Runner. As the most resourceful of this elite band of investigators, Matthew Hawkwood was surprised to be assigned the case – even if it did involve the murder and mutilation of a naval courier.From the squalor of St Giles Rookery, London's notorious den of theives and cutthroats, to the palatial homes of the aristocracy where knights of the realm conduct themselves in a manner unbecoming to their rank, Hawkwood relentlessly pursues his quarry.And as the case unfolds, and another body is discovered, the true agenda behind the robbery begins to emerge: the stolen naval dispatch pouch held details of a French plot that, if successful, will send the Royal Navy's entire fleet scurrying to port in terror, leaving Napoleon to rule the waves. With no way of knowing who can be trusted, Hawkwood must engage in a desperate race against time to prevent the successful execution of the Emperor's plot.

JAMES McGEE

Ratcatcher

CONTENTS

Cover (#u837f870c-ea42-50c5-aa71-9b3b9cd15da7)

Title Page (#uac0c3fbc-f08f-5570-8423-8ca7c59ffffa)

Prologue (#ud4b733a7-dd8b-50ea-b3dd-c30984f8cb34)

1 (#u39224d86-927b-5a56-9b87-7faf5f59b86a)

2 (#u95d024ff-893b-550a-9516-8eacefb73b2a)

3 (#ud14d7c40-af3b-5d8d-9931-30ef81a46588)

4 (#ud45d6cd1-929b-5797-bde8-6f97a0796bf4)

5 (#uf7f129fa-77c3-5232-87a6-b9ddf9129808)

6 (#litres_trial_promo)

7 (#litres_trial_promo)

8 (#litres_trial_promo)

9 (#litres_trial_promo)

10 (#litres_trial_promo)

11 (#litres_trial_promo)

12 (#litres_trial_promo)

13 (#litres_trial_promo)

14 (#litres_trial_promo)

15 (#litres_trial_promo)

16 (#litres_trial_promo)

17 (#litres_trial_promo)

18 (#litres_trial_promo)

19 (#litres_trial_promo)

20 (#litres_trial_promo)

21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Historical Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE (#ulink_73098197-647e-541d-84ec-9b10c3a2c883)

The prey was running late.

The horseman checked his pistol and returned the weapon to the leather holster concealed beneath his riding cloak. Bending low over the mare’s neck, he stroked the smooth, glistening flesh. At the touch, the animal whickered softly and stomped a forefoot into the soggy, waterlogged ground.

A large drop of rain fell from the branch above the rider’s head and splattered on to his sleeve. He cursed savagely. The rain had stopped thirty minutes before, but remnants of the storm still lingered. In the distance, a jagged flash of lightning sprang across the night sky and thunder rumbled ominously. Beneath him, the horse trembled.

The rain had turned the ground into a quagmire but the air smelled clean and fresh. Pale shafts of moonlight filtered through the spreading branches of the oak tree, illuminating the faces of the highwayman and his accomplice waiting in the shadows beneath.

The horses heard it first. Nervously, they began to paw the ground.

Then the highwayman picked up the sound. “Here she comes,” he whispered.

He pulled his scarf up over his nose and tugged down the brim of his hat until only his eyes were visible. His companion did the same.

The coachman was pushing the horses hard. Progress had been slow due to the foul weather and he was anxious to make up for lost time. The storm had made the track almost impassable in places, necessitating a number of unavoidable detours. They should have left the heath by ten o’clock. It was now close to midnight. The coachman and his mate, huddled beside him in a sodden black riding cape, were wet, tired, and irritable, and looking forward to a hot rum and a warm bed.

The coach had reached the bottom of the hill. Mud clung heavily to the wheel rims and axles and the horses, suffering from the extra weight, had slowed considerably. The driver swore and raised his whip once more.

By the time the coach crested the brow of the hill, the horses were moving at close to walking pace. Which was fortunate because it gave the driver time to spot the tree lying across the road. Hauling back on the reins, the driver drew the coach to a creaking standstill. Applying the brake, he climbed down to the ground and walked forward to investigate. A lightning bolt, he presumed, had been the cause of the obstruction. Another time-consuming detour looked a distinct possibility. The driver growled an obscenity.

It was the driver’s mate, perched atop the coach, who shouted the warning. Hearing the sudden cry, the driver turned, and started in horror as the two riders, their features shrouded, erupted from the trees. In the darkness, the horses looked monstrous.

“Stand where you are!” The rider’s voice bellowed out of the night. Moonlight reflected off the twin barrels of the pistol he pointed at the driver’s head. The driver remained stock-still, mouth ajar, terror etched on to his thin face.

The driver’s mate was not so obedient. With a muffled oath, he reached down for the blunderbuss that lay between his feet and swung the weapon up. His heavy rain-slicked cape, however, hampered his movements.

The highwayman’s accomplice reacted with remarkable speed. The night was split with the flash of powder and the crack of a pistol. The driver’s mate threw up his arms as the ball took him in the chest. The blunderbuss slipped from his weakened grasp and dropped over the side of the coach, glancing off a wheel before it struck the ground. The guard’s body fell back across the driving seat.

The first highwayman pointed his pistol at the terrified coachman. “You move, you die.” To his accomplice, he said, “Watch him while I take care of the rest.”

As his companion guarded the driver, the highwayman trotted his horse towards the coach. As he did so a large, pale face appeared at the window.

“Coachman! What’s happening?” The voice was male and, judging by the tone, belonged to someone used to wielding authority. “What’s going on out there?”

The passenger’s features materialized into those of a middle-aged man of lumpish countenance. His jaw went slack as his eyes took in the anonymous, threatening figure towering above him and the weapon aimed at the bridge of his nose.

The highwayman leaned out of his saddle. “All right, everybody out.” He motioned with the pistol, whereupon the gargoyle head withdrew sharply and the door of the coach opened.

The highwayman caught the cowering driver’s eye and jerked his head. “An’ you can join ‘em, culley. Move yourself!”

The driver, herded by the highwayman’s accomplice, backed timidly towards the coach, hands held high.

The passengers began to emerge. There were four of them.

A stout man in a dark tail coat, now identifiable as the individual who had stuck his head out of the window, was the first to descend, tiptoeing gingerly to avoid fouling his fine buckled shoes. Next was a woman, her face obscured by the hood of her cloak. She held out a hand and the stout man helped her down. She reached up and withdrew the hood, revealing a haughty, heavily powdered face. The highwayman clicked his tongue as the man pulled her to him and placed his arm protectively around her thin shoulders. Husband and wife, the highwayman guessed. She was too old and too damned plain to be his mistress.

The third person to step down from the coach was a slightly built man dressed in the uniform of a naval officer; dark blue cloak over matching jacket and white breeches. The face beneath the pointed brim of his fore and aft cocked hat showed him to be younger than his fellow passengers, though he appeared to alight from the coach with some difficulty, like an old man suffering from ague. He winced as his boot landed in the mud. His brow furrowed as he took in the two riders. Glancing up towards the driver’s seat, his expression hardened when he saw the still, lifeless body of the guard.

The last occupant to step down caused the highwayman to smirk behind his scarf. The man was elderly and cadaverous in appearance. He was clad entirely in black, the wispy white hair that poked from beneath his hat an almost perfect match for the white splayed collar that encircled his scrawny neck.

“All right, you know what to do.” As he spoke, the highwayman lifted a leather satchel from the pommel of his saddle and tossed it to the driver. “Hold on to that. The rest of you drop your stuff in the bag. Quickly now. We ain’t got all bleedin’ night!” The pistol barrels moved menacingly from passenger to passenger. “And that includes the bauble around your neck, Vicar.”

Instinctively, the parson’s hand moved to the cross that hung from his neck on a silver chain. “You’d dare steal from a man of the cloth?”

The highwayman gave a dry laugh. “I’d take Gabriel’s horn if I could get a good price for it. Now, ‘and the bloody thing over!”

Obediently, the parson lifted the chain over his head and lowered it carefully into the satchel. The driver’s hands shook as he received the offering.

“By God! This is an outrage!”

The protestation came from the passenger in the tail coat, who, with some difficulty, was attempting to remove a watch chain from his waistcoat pocket. Beside him, the woman shivered, wide-eyed, as she fingered the gold wedding band on her left hand.

“Come on, you old goat!” the highwayman snapped. “The ring! Sharply now, else I’ll climb down and take it off myself. Maybe grab a quick kiss, too. Though I dare say you’d like that, wouldn’t you?”

Horrified, the woman shrank back, twisted the ring off her finger and dropped it into the bag. A flicker of anger moved across the naval officer’s face as he lifted a small bag of coin from an inner pocket and tossed it into the satchel. Drawing his cloak around him, he stepped away.

“Whoa! Not so fast, pretty boy. Ain’t we forgetting something?”

The air seemed suddenly still as the highwayman gestured with his chin. “What’s that you’ve got hidden under your cloak? Hoping I wouldn’t notice, maybe?”

The officer’s jaw tightened. “It’s nothing you’d be interested in.”

“Maybe it is, maybe it ain’t.” The highwayman lifted his pistol. “Let’s take a look, though, shall we?” Wordlessly, after a moment’s hesitation, the passenger lifted the edge of his cloak to reveal his right hand, holding what appeared to be a leather dispatch pouch, but unlike any the highwayman had seen before. What made it different were the flat bands of metal encircling the pouch and the fact that the bag was secured to the passenger’s wrist by a bracelet and chain.

The highwayman threw his accomplice a brief glance. His eyes glinted. “Well, now,” he murmured, “and what’ve we got here?”

“Papers,” the man in the cloak said, “that’s all.”

The highwayman’s eyes narrowed. “In that case, you won’t mind me takin’ a look, will you?” The highwayman handed the reins of his horse to his companion, and dismounted.

Walking forward, the highwayman waggled his pistol to indicate that the young man should move apart from the other passengers. With his free hand, he snapped his fingers impatiently. “Key!”

The officer shook his head. “I don’t have a key. Besides, I told you, it holds nothing of value.”

“I won’t ask you again,” the highwayman said. He raised the pistol and pointed the twin muzzles at the officer’s forehead.

“Are you deaf, man? I don’t have a damned key!”

The highwayman snorted derisively. “You expect me to believe that? Of course you’ve got a bloody key!”

The officer shook his head again and sighed in exasperation. “Listen, you witless oaf, only two people possess a key: the person who placed the papers in the pouch and locked it, and the person I’m delivering them to. You can search me if you like.” The young man’s eyes glittered with anger. “But you’d have to kill me first,” he added. The challenge was unmistakable. Kill a naval officer and suffer the consequences.

It was a lie, of course. The key to the bracelet and pouch was concealed in a cavity in his boot heel.

The highwayman stared at the passenger for several seconds before he shrugged in apparent resignation. “All right, Lieutenant. If you insist.”

The pistol roared. The look of utter astonishment remained etched on the young man’s face as the ball took him in the right eye. The woman screamed and collapsed into her husband’s arms in a dead swoon as the officer, brain shattered by the impact, toppled backwards into the mud. He was dead before his corpse hit the ground.

Holstering the still smoking pistol, the highwayman sprang forward and began to rifle the dead man’s pockets. Several articles were brought to light: a handkerchief, a silver cheroot case, a pocket watch, a clasp-knife and, to the highwayman’s obvious amusement, a slim-barrelled pistol. The highwayman stuffed the cheroot case, knife and watch inside his coat. The pistol, he shoved into his belt.

“By Christ, I’ll see you both hanged for this!” The outburst came from the tail-coated passenger, who was still cradling his stricken wife. Beside him, the parson, grey-faced, had dropped to his knees in the mire. Whether at the shock of hearing the Lord’s name being taken in vain or in order to be sick, it was not immediately apparent.

The threat was ignored by the highwayman, who continued to ransack the corpse, his actions becoming more frantic as each pocket was inspected and pronounced empty. Finally, he threw his silent accomplice a wide-eyed look. “He was right, God rot him! There ain’t no bleedin’ key!”

In desperation, he turned his attention to the dispatch pouch. His hands traced the metal straps and the padlock that secured them.

Finding access to the pouch beyond his means, the highwayman examined the chain and bracelet. They were as solid and as unyielding as a convict’s manacle. He rattled the links violently. The dead man’s arm rose and flopped with each frenzied tug.

“Christ on a cross!” The highwayman threw the chain aside and rose to his feet. In a brutal display of anger, he lifted his foot and scythed a kick at the dead man’s head. The sound of boot crunching against bone was sickeningly loud. “Bastard!”

He stepped away, breathing heavily, and regarded the body for several seconds.

It was then that he felt the vibrations through the soles of his boots.

Hoofbeats. Horsemen, approaching at the gallop.

“Jesus!” The highwayman spun, panic in his voice. “It’s the Redbreasts! It’s a bloody patrol!” He stared at his companion. An unspoken message passed between them. The highwayman turned back and stood over the sprawled body. He reached inside his riding coat.

In a move that was surprisingly swift, he drew the sword from the scabbard at his waist. Raising it above his head, he slashed downwards. It was a heavy sword, short and straight-bladed. The blade bit into the pale wrist with the force of an axe cleaving into a sapling. He tugged the weapon free and swung it again, severing the hand from the forearm. Sheathing the sword, the highwayman bent down and drew the bracelet over the bloody stump. He turned and held the dispatch pouch aloft, the glow of triumph in his eyes.

As if it were an omen, the sky was suddenly lit by a streak of lightning and an ear-splitting crack of thunder shattered the night. The storm had turned. It was moving back towards them.

Meanwhile, from the direction of the lower road, beyond the trees, the sound of riders could be heard, approaching fast.

The highwayman tossed the dispatch pouch to his accomplice, who caught it deftly. Then, stuffing his pistol into its holster and snatching the satchel containing the night’s takings from the startled coachman, he sprinted for his horse. Such was his haste that his foot slipped in the stirrup and he almost fell. With a snarl of vexation, the highwayman hauled himself awkwardly into the saddle and his accomplice passed him the reins.

Rain began to patter down, striking leaves and puddles with increasing force as the highwayman and his still mute companion turned their horses around. The sound of hooves was clearly audible now, heralding the imminent arrival of the patrol; perhaps a dozen horsemen or more.

The two riders needed no further urging. Wheeling their horses about, digging spurred heels into muscled flanks, they were gone. Within seconds, or so it seemed to the bewildered occupants of the coach, swallowed up by the night, the sound of their hoofbeats fading into the darkness beyond the moving curtain of rain.

1 (#ulink_8b5fab94-d416-5fdd-962c-174a9b59388b)

It had quickly become clear to the crowd gathered in the stable yard behind the Blind Fiddler tavern that the Cornishman, Reuben Benbow, the younger of the two fighters, was far more accomplished than his opponent. The local man, Jack Figg, was heavier built and by that reckoning, a good deal stronger, but there was little doubt among those watching that Figg did not have anything to match his opponent’s agility.

The Cornishman was tall, six feet of honed muscle, with features still relatively unscathed. Having served his apprenticeship in fairground booths the length and breadth of his home county, he had been taken under the protective wing of Jethro Ward, the West Country’s finest pugilist. Under Ward’s diligent tutelage, Benbow was fast gaining a reputation as a doughty, if not ruthless, fighter.

Jack Figg, on the other hand, was square built with a face that betrayed the legacy of half a lifetime in the bare-knuckle game. A stockman by trade, it was said that in his youth Figg could stun a bullock senseless with one blow of his mighty fist, and that he had once sparred with the great Tom Cribb. But now Figg was past his prime. His body bore the scars of more than seventy bouts.

The opening seconds of the new round were an indication that Figg was continuing with the close-quarter approach; a technique to be expected. Only too aware that he was slower and less nimble than his opponent, he was attempting to exploit his size and strength by grappling his man into submission. The rules of the fight game were simple and few: no hitting an adversary below the waist. Any other tactics that might be employed were considered perfectly acceptable, even if it meant breaking your opponent’s back across your knee.

Benbow, however, had been well coached and was wise to the older man’s game. He knew if he could keep out of Figg’s reach he would eventually tire out his opponent. There was no knowing how long a fight could last – forty, fifty, perhaps as many as sixty rounds – which meant the fitter man would inevitably prevail. The majority of bouts were decided not by knockout but by the loser’s exhaustion. Besides, full blows often led to shattered knuckles and dislocated forearms and as the hands became swollen so they began to lose their cutting power. Much better to wear away your opponent’s defences with short jabs. In any case, a quick finish would certainly displease the crowd.

The afternoon bout had attracted several hundred spectators. Workers from the timber yards rubbed shoulders with Smithfield porters, while Shoe Lane apprentices jostled for space with ostlers from the nearby public houses. The latter formed the rowdiest contingent, heckling the Cornishman mercilessly, protesting vigorously whenever Figg received what was perceived to be a foul blow, and cheering wildly on the occasions their hero managed to retaliate.

There were other, more respectably dressed onlookers: square-riggers, toffs and dandies who’d forsaken their own haunts among the fashionable clubs of Pall Mall and St James’s in order to savour the delights offered by the less salubrious parts of the capital. Enticed by the flash houses with their cheap whores who were only too eager to accept a coin in exchange for a quick fumble in a dark alleyway or in some rat-infested lodging house, a prizefight and the lure of a wager were added attractions. Dotted around were several men in uniform, a smattering of army officers and a raucous group of blue-jackets on shore leave from the Pool.

Hawkers and pedlars moved among the crowd, while at the edge of the throng, beneath the cloisters, mothers suckled infants, and snot-nosed children crawled on hands and knees between the legs of the adults, oblivious to the filth that coated the cobblestones. A tribe of limbless beggars masquerading as wounded veterans appealed for alms, while beside them drunks sprawled comatose in the gutter. In one corner of the yard a mullet-faced individual with the staring gaze of the fanatic teetered on a wooden box and railed vexedly against the sins of the flesh and the evils of gambling.

Prizefighting was unlawful. So around the perimeter of the yard lookouts patrolled the entrances and alleyways, ready to warn the fighters and spectators of the arrival of the constables. Were a warning to be given, the ring would be dismantled within minutes, leaving the fighters and their promoters to melt into the crowd.

There were other parties in attendance, too, interested in neither prizefight nor preacher. These were creatures of a different kind, opportunists drawn by the whiff of rich pickings, thieves of the street.

The pickpocket was nine years old. Stick thin, small for his age, known to his associates as Tooler on account of his skill at winkling his way into a crowd to relieve a mark of wallet and watch in less time than it took to draw breath. A graduate of the Refuge and Bridewell, and a thief since the age of four, by now he was an old hand at the game.

Tooler had had his eye on the mark for a while. The crowd was dense and there were plenty of distractions on hand to mask the approach and snatch. Tooler scanned the boundary of the mob, checking his escape route. Jem Whistler, Tooler’s stickman and his senior by a year and two months, wiped a crumb of stolen mutton pie from his lips and nodded slyly. The two barefooted urchins threaded their way towards their intended victim.

To the crowd’s delight Figg had begun to stage a comeback. A number of his blows were landing, admittedly more by luck than judgement, but the Cornishman’s upper body was at last beginning to show signs of wear and tear.

Spurred on by his supporters, Figg aimed a roundhouse blow at his opponent and the crowd roared. If the punch had connected, the fight would have been over there and then, but Benbow parried the uppercut with his shoulder and scythed a counterstrike towards Figg’s heart. Figg, wrong-footed with fatigue, shuddered under the impact. Pain lanced across his bruised and battered face. Blood dribbled from his nostrils. His shaven scalp was streaked with sweat.

Tooler’s mark was a red-haired, florid-faced individual dressed in the scarlet jacket and white breeches of an army major. He was standing with his companion, also in uniform, beneath one of the stable arches. Head down, with Jem dogging his heels, Tooler made his approach from the major’s right side.

In the ring, Figg launched a massive blow to the Cornishman’s ribcage and the crowd sucked in its collective breath as Benbow took the punch over his kidneys. The mob clamoured for more.

Amid the excitement, Tooler seized his opportunity. His light fingers brushed the major’s sash, unhooking the watch chain in one swift movement. In the blink of an eye, the watch was passed underarm to Jem Whistler’s outstretched hand. Turning immediately, Tooler and his stickman separated and within seconds the two boys had dissolved into the crowd, with neither the major nor his companion aware that the theft had taken place.

Behind them, Benbow was responding hard. Figg wilted under the Cornishman’s two-fisted attack. Blood and mucus flowed from his split nose as the mob shouted itself hoarse. There was no finesse in the way the two fighters traded blows. The bout had degenerated into a ferocious brawl. So fierce was the battle that the spectators closest to the ringside were splattered with gore.

Ignoring the growing excitement, the two pick-pockets weaved their way through the mass of bodies. At the rear of the yard lay the entrance to a narrow alley. The boys ducked into it, unheeded by the lookouts, who were more interested in the outcome of the fight and scanning the area for uniformed law officers than the passing of two grubby children. In no time Tooler and his stick-man had left the babble of the stable yard and entered the maze of lanes that lay behind the inn.

As they picked their way through dark, damp passages lined by walls the colour of peat, the boys paid little attention to their surroundings. They were on familiar ground in this netherworld of densely packed tenements and grim lodging houses; buildings so old and decrepit it hardly seemed possible they were still standing. An open cess trench ran down the middle of each alley. Rats skittered in the shadows. The waterlogged carcass of what could have been either animal or human floated in the effluent. Vague, sinister shapes haunted dark doorways or hovered in silhouette behind candlelit windows. Only the occasional voice raised in anger indicated that the slum was inhabited by humankind. With the late afternoon sun sinking slowly below the cluttered rooftops, the boys hurried deeper into the warren.

Mother Gant’s lodging house was nestled into the side of a small courtyard at the end of a hip-wide passage. With its overhanging eaves, narrow doorway and dirt-encrusted windows, it was typical of the many doss houses that infested the area. A tumbledown sty occupied one corner of the yard. Two raw-boned pigs rooted greedily in an empty trough. They looked up, snouts thrusting, grunting with curiosity as the boys ran past.

The hovel was low roofed, dim lit and smoky. The soot-blackened walls were of bare brick, the floor unboarded. A hearth ran along one wall. An oaken table took up the middle of the room. Seated around it were a dozen children of both sexes. Pale, unwashed, dressed in threadbare clothing, they ranged in age from six to sixteen. An old woman, garbed in black with a tattered shawl around her shoulders, stood at the hearth, ladling the contents of a large cooking pot. She looked up as the boys entered. In the flickering glow from the coals, her rheumy eyes glittered.

No one knew Mother Gant’s age, only that she had run the lodging house for as long as anyone in the neighbourhood could remember. It was well known that she had outlived three husbands; two had succumbed to disease, the third had disappeared one dark night never to be seen again. Rumour had it that the latter had been dropped into the river, his throat slit from ear to ear, after a tavern brawl. A drunkard and a wastrel, he had not been missed, certainly not by the Widow Gant.

The children seated around the table were not Mother Gant’s blood kin. The old lady had been named not for the size of her own brood but due to her habit of taking in waifs and strays. This display of generosity was not born of a sense of charity. It was greed that made Mother Gant open her doors to the orphans of the borough. She expected her young tenants to pay for the roof over their heads and the food in their bellies. And the rent she exacted was not coin of the realm – though that would not have been refused – it was contraband.

Mother Gant was a receiver of stolen property. She took in her orphans, she fed them and she housed them. Then she trained them and sent them out into the streets to steal for their supper. And woe betide anyone who returned empty-handed.

Fortunately for Tooler and Jem, their afternoon’s activity had yielded a good haul: three watches, two breast pins, a silver snuffbox, and no less than four pocketbooks. As the proceeds were deposited on the table, Mother Gant left the cooking pot and cooed softly to herself as she sifted through the valuables.

“You’ve done well, boys,” she simpered. “Mother’s very pleased.”

The old woman picked up the silver snuffbox and turned it over in her hands. Lifting the lid, she placed a pinch of snuff delicately on to the back of her hand, lowered her head and snorted the powder up each nostril in turn. Snapping shut the lid, she wiped her nose on her sleeve, grinned ferally, and slipped the box into her pocket.

“Extra helpings tonight, my lovelies,” she whispered, hobbling back towards the hearth. “Them as works the ‘ardest deserves their reward. Ain’t that right?”

At which point a long shadow fell across the open doorway.

“Hello, Mother – got room for one more?”

Mother Gant’s eyes blazed with alarm as the visitor stepped into the room.

The man was tall and dressed in a midnight-blue, calf-length riding coat, unbuttoned to reveal a sharp-cut black waistcoat, grey breeches and black knee-length boots. He was bareheaded. The face was saturnine, the hair black, streaked with grey above the temple. What was unusual, given the fashion of the time, was his hair, which was worn long and tied at the nape of the neck with a length of black ribbon. Below the man’s left eye, a small ragged scar was visible along the upper curve of his cheekbone.

If Matthew Hawkwood had expected an extreme reaction to his entrance, he was not disappointed. Even as his gaze fell upon the pile of stolen artefacts, the room erupted.

Stools and benches were overturned as the children scattered like rabbits before a stoat. In a move that was remarkably sprightly, the old woman twisted and hurled the soup ladle towards the new arrival, at the same time letting loose a high-pitched screech. Whereupon the massive figure seated in the corner of the room who had, up until that moment, remained still and silent, rose to its feet.

All told, Mother Gant had given birth to three sons and one daughter. Her first-born son had been smitten by the pox, the manner by which her first and second husbands had met their demise. Her second son had also been taken from her, but not by illness. Press-ganged at the age of sixteen, consigned to a watery grave at the age of eighteen, his innards turned to gruel by a ball fired from a French frigate during an engagement off the coast of Morocco. As for the daughter, no one knew her exact whereabouts. Last heard of, she was earning a precarious living as a whore, working the streets and arcades of Covent Garden and the Haymarket. Which left Mother Gant’s youngest son, Eli, as the only child not to have flown the coop. Though, if the truth were told, it was doubtful if the youth could have survived the separation.

At the age of twenty, Eli had the neck and shoulders of a wrestler, forearms the size of oak saplings, and the hands of a blacksmith. But though he possessed the body of a man, he had the brain of an infant. Unable to fend for himself or perform anything beyond the most menial tasks, he had become little more than a chattel to his widowed mother, who used him as she might have done a dray horse: as a beast of burden. On the occasions that she conducted the more nefarious of her enterprises, however, she used his size and strength for intimidation and protection. Eli’s sole purpose in life was to serve his mother, a duty he carried out unconditionally.

As Tooler and Jem and the other children ran for the door, the lumbering, moon-faced figure of Eli Gant emerged from the gloom. Hearing Mother’s cry, Eli was reacting solely on instinct. The shrill note in the old woman’s voice told him that there was trouble and that she needed his help. That was all he needed to know. When he rose to his feet, the cudgel that had been propped against the arm of the chair was in his hand.

Hawkwood avoided the thrown soup ladle with ease. As the utensil clattered against the wall a flicker of amusement passed over his face. Then he caught sight of the apparition looming towards him and his expression changed. He turned to confront the new threat.

“Stop him, Eli! He’s here to hurt Mother!” The old woman’s voice pierced the room.

The attack, when it came, was sudden. For a man of his huge bulk, Eli Gant moved with surprising speed.

But Hawkwood was quicker. Even as the cudgel was raised, he swung his foot and kicked Gant hard between the legs. Eli’s jaw went slack. Dropping the club, he doubled over. A baton appeared in Hawkwood’s hand. Without losing momentum, he sidestepped and drove the short club viciously against the side of Gant’s head. The ground shook as Gant’s body hit the earthen floor. Staring down at the wheezing, prostrate form, Hawkwood shook his head wearily. He’d seen it all before.

When he looked up, Mother Gant had disappeared.

Hawkwood cursed and turned. “Rafferty!”

A bulky figure materialized behind him. Red-faced and coarse-featured, wearing the uniform of a conductor of the watch: black felt hat, double-breasted blue jacket and matching waistcoat. His eyebrows rose as he took in the man on the ground.

His eyes widened further as Hawkwood leapt over the stricken Gant, crossed the room and ripped away the ragged curtain that hung on a rail on the opposite wall. Concealed behind the curtain was an open doorway. Pausing on the threshold, Hawkwood peered into the darkness that lay beyond. A cold draught caressed his face and a vague shuffling noise sounded from somewhere ahead, then his eyes caught the feeble glow of a lantern and a hunched, dark-clothed figure scurrying away. Mother Gant, having abandoned her idiot son to guard her back, was on the run.

Hawkwood knew he had to act quickly. There was no telling how far the tunnel stretched or where it emerged. Given the nature of the area, it was likely the shaft led into a honeycomb of passages, trap doors, hidden stairwells and twisting alleyways running above and below ground level. And the old woman, of course, would know the place like the back of her crabby hand.

There was no time to find a lantern of his own. He’d have to rely on the faint light ahead of him as a guide. He turned and nodded past the constable’s legs to where the hapless Eli Gant was still curled foetally on the floor. “Watch him.” Clasping the baton firmly, he plunged into the hole.

The smell was dreadful. It was the stench of damp and decay, pungent enough to clog the nostrils and make the eyes water. The floor of the tunnel was firm underfoot, but here and there the ground squelched alarmingly, sucking at his heels. More than once, his ears picked up the faint squeak of rodents and he felt the soft touch of their tiny paws as they ran across the toe of his boot.

It was hard to tell what the walls were made of. Sometimes his fingers brushed brick, sometimes wood, often so rotten it flaked off in his hand. Similarly, it was impossible to determine if it was sky over his head or stone. As his eyes grew accustomed to the dimness, he began to make out openings in the tunnel walls: junctions leading to even more escape routes. Occasionally, through a chink in a wall, he caught a glimmer of light, the flicker of a candle flame, a sign that somewhere within this strange subterranean world there existed vermin of a higher intellect than rats and mice. And always the fluttering lantern carried by the Widow Gant drew him further into the maze.

Abruptly, the glow ahead of him died. He paused, listening. He moved forward cautiously, senses alert for the slightest movement. He wondered how far he had come. It seemed like a mile, but in the darkness, distance was deceptive. It was probably no more than a hundred paces, if that.

He could just make out a pale crescent of light ahead. It appeared to be low down, perhaps an indication that there was a dip in the tunnel or a stairway. And then he saw there was a bend in the passage. He continued slowly, the baton held tightly in his fist.

He turned the corner and saw that the lantern had been placed on the ground next to what looked to be the old woman’s shawl. He bent to examine it.

It was then that the wizened, bat-like creature detached itself from the wall to his right, accompanied by a scream of such intensity it was almost impossible to imagine the source could be human.

Even as he turned, dropping the shawl, the glow from the lantern caught the glint of the knife blade as it curved towards his throat. Hawkwood hurled his body aside. The sliver of steel whipped past his face and he heard the grunt as the old woman realized she had missed her target. Christ, but she was fast! Faster than he would have thought possible, and hate had given her added impetus. Already she was turning again, driving the weapon towards his heart.

He felt the cloth tear on his upper arm as the razor-sharp blade sliced through his coat sleeve, the material parting like grape skin. Transferring the baton to his left palm, he struck upwards to turn the strike away, at the same time reaching for her wrist with his other hand. Her arm was no thicker than a child’s, but the power in the reed-thin body was astonishing. His fingers encircled her wrist, deflecting the blade’s cutting edge. At the same time, he struck down with the baton and heard the brittle snap of breaking bone. The knife dropped to the floor and her squeal of pain reverberated off the walls.

But, incredibly, she wasn’t finished. In the next second, her left hand was reaching towards his face as she launched herself at him, spitting and swearing as if possessed by devils, clawing for his eyes with nails as sharp as talons. So ferocious was the force of her attack, he was slammed against the wall of the tunnel. Air exploded from his lungs.

One-handed, she clung to him, kicking and gouging. Flecks of spittle landed on his face. He felt, too, her hot breath on his cheek, as rancid as a midden, and knew that somehow he had to finish it. He hooked the end of the baton into her stomach, felt the grip on his collar loosen, used his full body weight to drive his fist under her ribcage and punch her away.

There was a flat thud as the back of her head hit the wall, the screech dying on her lips as her frail body slid to the ground. She landed awkwardly, winded, legs akimbo, dress around her knees, thin breasts rising and falling as she gasped for air.

Hawkwood straightened and wiped the smear of phlegm from his jaw.

“Bitch.”

The crumpled figure at his feet let out a low moan.

Slipping the ebony baton inside his coat, he bent to retrieve the discarded shawl. He used the shawl to bind her wrists, making no allowances for the broken arm. In the vapid glow from the lantern, he could see that her eyes were glazed with pain. Her resistance was clearly spent.

When he had finished trussing her arms, he picked up the lantern. Holding it aloft, he lifted the old woman by the collar of her dress and began to retrace his steps down the tunnel, dragging her limp, unprotesting body behind him.

2 (#ulink_0ba0fa65-9042-56d0-aa0c-22fe3f499169)

In the kitchen of the house, Constable Edmund Rafferty scratched his ample belly and gazed at the display of valuables on the table. He cast a wary eye on the figure of Eli Gant who, having recovered from the baton blow, was seated on the floor, his back to the wall, rocking slowly from side to side, while staring mournfully down at the handcuffs that had been fastened around his wrists. In his present predicament, he looked as harmless as a puppy.

Rafferty stole another surreptitious glance at the table and started as a voice behind him said, “We caught four of the little beggars, Irish. What should we do with ‘em?”

The speaker was a thin, ferret-featured individual dressed similarly to Rafferty, save for the colour of his waistcoat, which was scarlet instead of blue. His right hand was clamped around the collar of a small boy. He was holding the boy in such a way that the tips of the child’s toes only just touched the cobbles. The child was trying to pull away. His attempt to escape, however, was instantly curtailed when his captor cuffed him violently round the back of the head.

Rafferty eyed the figure at the door with scorn. “You hold on to ‘em, Constable Warbeck, until I tells you otherwise. Now, take him outside, there’s a good lad.”

The constable touched his cap and moved away, and Rafferty breathed a sigh of relief. It was Rafferty’s considered opinion that Constable Warbeck hadn’t the brains he’d been born with, and his habit of addressing Rafferty as “Irish” was also beginning to irk considerably. Unfortunately, Warbeck was married to Rafferty’s younger sister, Alice, who had persuaded her brother to sponsor Warbeck’s entry into the police force; an act of charity about which he was beginning to have severe misgivings. Not least, regarding the said constable’s apparent inability to look the other way at opportune moments. Clearly, the man had much to learn. Still, Rafferty concluded, it was early days.

Moving to the table, Rafferty eyed the small array of pocketbooks and jewellery with increasing interest. Looking over his shoulder to ensure he was not being observed, he investigated the contents of the pocketbooks. Several of them, to his delight, held banknotes. He extracted one crisp note from each and replaced the pocketbooks on the table. Then his eyes alighted on the watch.

It was a very fine watch; gold-cased, with matching chain. Undoubtedly the property of a gentleman. Rafferty held the timepiece up to his ear. The ticking was like a tiny heartbeat. He inserted the end of a blunt fingernail under the clasp and was about to flick open the cover when his ears detected footsteps and a curious scraping sound. Quickly, Rafferty dropped the watch into the deep pocket of his coat. Just in time. He grinned expansively as Hawkwood emerged from behind the curtain, dragging the body of Mother Gant into the room.

“Well now, Captain, there I was wondering where you’d got to. Thought we might have to send out a search party, so I did.” Rafferty’s glance dropped to the body of the Widow Gant, who had regained consciousness and was staring up at Hawkwood with a degree of malevolence that was chilling in its intensity.

“See you caught the old crone, then?” Rafferty studied the rent in Hawkwood’s sleeve and frowned. “Gave you a bit of trouble, did she?”

Hawkwood hauled the old woman across the floor and dropped her next to her son. When he looked up his eyes were as dark as the grave.

“How many?”

Rafferty sighed. “Four. The rest scarpered. My lads’ve got ‘em outside.” Rafferty found himself wavering under the other man’s gaze. There was something in that hard stare that made Constable Rafferty’s blood run cold. To his relief, Hawkwood merely nodded in acceptance.

“Probably as many as we deserved. All right, you know what to do. Take them away.”

Rafferty nodded. “Right you are.” The constable aimed a kick at Eli Gant’s shin. “On your feet! You, too, Mother, else you’ll get my boot up your skinny arse!”

Hawkwood turned away as Rafferty bundled his charges out of the house.

“Wait!”

The command cut through the air. Rafferty paused on the doorstep. A cold wind touched his spine. When he turned around he found that Hawkwood was looking at him, and his breath caught in his throat.

The bastard knew!

Hawkwood held out his hand. “I’ll take the watch, Rafferty.”

“Eh?” Instinctively, in voicing that one word of feigned innocence, Rafferty knew he’d betrayed his guilt. Conceit and fear, however, dictated that he make at least a half-hearted attempt to extricate himself from the mire.

“Watch? And what watch would that be, then? Sure, and I don’t know what you mean.”

Hawkwood’s expression was as hard as stone. “I’ll ask you once more, Constable. You’ve already made one mistake. Don’t compound the error. Hand it over.”

Even as he blustered, Rafferty knew the game had been played to its conclusion. His only recourse was to try and retire with as much bravado as he could muster. He frowned, as if searching his memory, and then allowed a broad smile to steal across his face.

“Och, sweet Mary! Why, of course! What was I thinking? Sure and didn’t I just slip it into my pocket for safekeeping and then forget all about it? Memory’ll be the death of me, so it will. Here it is, now! I’m glad you reminded me, for it’s likely I’d have walked off with it, so I would.”

And with a grin that would have charmed Medusa, Constable Rafferty reached into the pocket of his coat and brought forth the watch with the dexterity of an illusionist producing a rabbit from a hat.

“There you go, Captain.” Rafferty handed the watch over. “And a very fine timepiece it is, too, even if I does say so myself. Cost a pretty penny, I shouldn’t wonder.” A mischievous wink caused the right side of the constable’s face to droop alarmingly. “Take a bit of a liking to it yourself, did you? And who’d blame you, is what I’d say. Why, I –”

Hawkwood turned the watch over in his hands and looked up. His expression was enough to erase the grin from the constable’s face.

“You can dispense with the bejesus and the blarney, Rafferty. It might fool the ladies and the scum you drink with, but it doesn’t impress me.”

Rafferty’s skin reddened even further and he shifted uncomfortably, but Hawkwood hadn’t finished.

“A warning, Rafferty. You ever work with me again, you’d best keep your thieving hands to yourself. Otherwise, I’ll cut them off. Is that clear?”

The constable opened his mouth as if to protest, but the words failed him. He nodded miserably.

“Good, then we understand each other. The watch stays with me. Take the rest of the loot to Bow Street. It can be stored there as evidence. And mark this, Rafferty. I’m holding you responsible for its safe arrival. You never know, the owners may actually turn up to claim it. Now, get the hell out of my sight.”

Hawkwood waited until Rafferty and his constables had left with their prisoners, before flicking open the watch cover and reading the inscription etched into the casing. Then, closing the watch, he dropped it into his pocket and let himself out of the house.

In the stable yard behind the Blind Fiddler, the fight was nearing the end. It was the forty-seventh round. By the standards of the day, and by common consent, it had been an enjoyable contest.

Both fighters had taken severe punishment. Benbow, his face a mask of blood and nursing two broken ribs, waited for his opponent to come within range.

Figg, rendered almost deaf and blind by the injuries he had received, his wrists and hands swollen to twice normal size, wits scrambled by a barrage of punches to the face and leaking sweat from every pore, spat out a gobbet of blood, and circled unsteadily.

Both men could barely stand.

The end, when it came, proved to be something of an anti-climax. Benbow, swaying precariously, hooked a punch towards his opponent’s belly. The blow landed hard. Figg collapsed. Blood gushed from his mouth, and the crowd groaned. It was a certain indication that Figg’s lungs had been damaged. The sight was sufficient cause for the referee, in a rare display of compassion, to end the contest and award the bout to the Cornishman.

So suddenly was the decision announced that a hush fell over the spectators. But then, like ripples spreading across a pond, an excited chatter began to spread through the assembled gathering. Benbow sat down on a low stool, probed his mouth with a finger, spat out a tooth, took a swig from a proffered brandy bottle, and looked on without pity as the defeated Figg was helped away by his seconds.

Beneath the stable arch, the red-haired major clapped his companion on the back and shook his head in admiration. “By God, Fitz, that was as fine a contest as I’ve witnessed, and I’m ten guineas better off than I was before the bout, thanks to the Cornishman. Damn me, if winning hasn’t given me a raging thirst. What say we wet our whistles before we meet the ladies? I do believe we’ve an hour or two to kill before we’re expected.”

The major reached into his sash and his face froze with concern. “Hell’s teeth, Fitz! My watch and chain! Gone! I’ve been robbed!”

The two men looked about them. A futile gesture, as both were fully aware. Whoever the thief was, he or she was long gone, swallowed up by the rapidly dispersing crowd.

“Damn and blast the thieving buggers!” The major swore vehemently and gritted his teeth in anger and frustration.

It was the sense of someone at their shoulder that caused them both to turn. The red-haired officer’s first impression was that the stranger was a man of the cloth. The dark apparel hinted as much, but as the major took in the expression in the smoke-grey eyes he knew that the man was certainly no priest. It was then the major saw the object held in the stranger’s open hand.

“I’ll be damned, Fitz! Will you look at this! The fellow has my watch! May I enquire how the devil you came by it, sir?”

Hawkwood held the watch out. “Sorry to disappoint you, Major, but sorcery had nothing to do with it. I spotted the boy making the snatch. As for the rest, let’s just say that I persuaded him to see the error of his ways.”

Reunited with his property, the major could not disguise his joy. Clasping the watch in his fist, he smiled gratefully. “Well, I’m obliged to you, sir, I truly am. It’s fortunate for me you’ve good eyesight. But here, I’m forgetting my manners. Permit me to introduce myself. The name’s Lawrence, 1st Battalion, 40th Light Infantry. My companion, Lieutenant Duncan Fitzhugh.”

The younger officer gave a ready smile and touched the peak of his shako. “Honoured, sir.”

Hawkwood did not reciprocate. Instead, to the surprise of the two officers, he merely gave a curt nod of acknowledgement and turned away.

The major was first to protest. “Why, no! Stand fast, sir! You’ll allow me the opportunity to express my gratitude. The watch means a great deal to me. The lieutenant and I were about to partake of a small libation. You’ll join us, of course?”

“Thank you, no.” Hawkwood’s reply was abrupt.

“But, sir!” the major remonstrated. “I insist –”

Skilfully interpreting the expression on Hawkwood’s face, the lieutenant took his companion’s arm. “You’d best let him go, sir. You’re embarrassing the poor fellow.”

The major made as if to argue, but then changed his mind and shrugged in acceptance. “Oh, very well, but it don’t alter the fact that I’m indebted to you. If I can repay the favour in any way …” The major’s voice trailed off. Putting his head on one side, he frowned. “Forgive me, sir, this may seem an odd question, but have we met before?”

Hawkwood shook his head. “Not to my knowledge, Major.”

“You’re certain? Your face seems familiar.” The major narrowed his eyes.

“Quite certain.” Hawkwood inclined his head. “Good day, Major … Lieutenant.” Then he turned on his heel and strode away without a backward glance.

“Damned odd,” the major murmured. He paused, looked around quickly, caught the eye of a hovering street vendor and crooked a finger. The hawker, scenting custom, touched his cap. The wooden tray suspended from a cord around his neck offered a variety of sweetmeats. Several bloated flies arose lazily from the tray. Fitzhugh wrinkled his nose in disgust.

The hawker grinned, showing blackened teeth. “Yes, your honour, what’s your pleasure?”

The major dismissed the proffered titbits with an impatient wave of his hand. Instead, he nodded across the yard. “The severely dressed fellow with the long dark hair, disappearing yonder. Do you know him?”

The man peered in the direction the major indicated. To the officers’ surprise, the hawker’s face appeared to lose colour. He eyed them suspiciously. “What’s it to you?”

Lawrence smiled easily and retrieved a coin from his pocket. “Curiosity, my friend, nothing more. His face looked familiar to me, that’s all.”

The hawker eyed the coin furtively, but only for a second before his thin fingers closed around it. Biting into the coin, he muttered darkly, “If I was you, your honour, where that one’s concerned, you’d best turn and walk the other way.”

Lawrence and Fitzhugh exchanged startled glances. “How so?”

“Because he’s the law, that’s why.”

Lawrence’s eyebrows rose. “The law?”

“Works out of Bow Street, don’t he? One of them special constables. Runners, we calls ‘em. Mean bastards every one.”

The two officers stared across the yard. The hawker spat on to the cobbles. “You take heed, friend. You ever find yourself in trouble, you’d best pray they don’t put him on your trail.”

“Well, I’m damned,” Lawrence said, adding, “but his name, man! Do you know his name?”

The pieman’s expression hardened. “Name? Oh, yes, I know his name, right enough. It’s Hawkwood, may God rot him. Now …” the hawker lifted his tray pointedly “… if you gentlemen ‘ave no intention of buyin’ …”

But the major wasn’t listening. He was staring off in the direction the dark-haired man had taken. He looked like a man in shock. It was Fitzhugh who finally dismissed the waiting pieman. Muttering under his breath, the vendor limped away.

Fitzhugh regarded his companion with concern. “Are you all right, sir? You look as though you’ve seen a ghost.”

Lawrence remained motionless and said softly, “Maybe I have.” He turned and favoured the lieutenant with a rueful smile. “By God, Fitz, memory’s a fickle mistress!”

“You do know him, then? You’ve met before?”

“We have indeed,” Lawrence said softly, adding almost abstractedly, “and both of us a damned long way from home.”

Fitzhugh waited for the major to elaborate, but on this occasion Lawrence did not oblige. Instead, the major nodded towards the door of the tavern. “I think I’m in need of a stiff brandy, young Fitz. What say you and I adjourn to yon hostelry and I’ll treat you to a wee dram out of my winnings?” Lawrence clapped his companion on the shoulder. “Who knows? I may even have an interesting tale to tell along with it.”

From the shadow of an archway, Hawkwood watched the major and his companion enter the inn. It had been a strange sensation seeing Lawrence again. In Hawkwood’s case, recognition had been immediate, confirmed by the engraving on the watch casing:

Lieutenant D.C. Lawrence, 40th Regiment.A gallant officer.

With grateful thanks, Auchmuty.February 1807

An inscription which could not be ignored. The watch was not merely an instrument for keeping time but a reward for services rendered; an act of outstanding bravery. The words alone indicated, to the recipient at least, that it was worth far more than gold. Hawkwood had seen the anguish on the major’s face when he’d discovered the loss.

It would have been an even greater crime had the watch remained in Constable Rafferty’s thieving clutches. Despite his warning to Rafferty, Hawkwood wondered just how many of the other stolen items would find their way back to their rightful owners. Precious few, he suspected. Sadly, men like Rafferty, guardians of the public trust with a tendency to pilfer on the side, were only too common.

Hawkwood’s thoughts returned to the major. His intention to return the watch had been instinctive. Call it duty, a debt of honour to a former comrade in arms, albeit one whose companionship had been fleeting in the extreme. There had been little hesitation on his part.

So, why deny recognition? The answer to that question was easy. Old wounds ran deep. Reopening them served no useful purpose. He shook his head at the thought of it. A chance encounter and it was as if the years had been rolled away. But sour memories were apt to leave a bitter aftertaste. What was done was done. He’d performed a service for which thanks had been given; a public servant performing a civic duty. That’s all it had been. Now it was over. Finished.

Hawkwood was about to step away when a discreet cough sounded at his elbow.

Shaken out of his reverie, he looked down and found himself confronted by a small, bow-legged, sharp-nosed man dressed in funereal black coat and breeches. An unfashionable powdered wig peeked from below the brim of an equally outmoded three-cornered black hat. Eyes blinked owlishly behind a pair of half-moon spectacles.

Hawkwood gave a wintry smile. “Well, well, Mr Twigg. And to what do we owe this unexpected pleasure?” As if he didn’t know.

The little man deflected the sarcasm with an exaggerated sigh of sufferance. “A message for you. Magistrate Read sends his compliments and requests that you attend him directly.”

Hawkwood’s eyebrows rose. “‘Requests’, Mr Twigg? I doubt that. And where am I to attend him, directly?”

“Bow Street. In his chambers.”

As he spoke, Ezra Twigg allowed his gaze to roam the stable yard. By now the crowd had all but disappeared. The God-botherer, sermon concluded, had dismantled his home-made pulpit and was steering a course for the tavern door. A handful of pedlars remained, ever hopeful of attracting late custom. Close by the ringside, a small knot of people had gathered. In their midst, Reuben Benbow, nursing cracked ribs, joked with his seconds and celebrated his hard-fought victory.

The bewigged clerk’s eyes took on a calculated glint. Removing his spectacles, he breathed on the lenses and polished them vigorously on the sleeve of his coat.

Hawkwood grinned. “You were right, Ezra. The Cornishman was the better man.”

Ezra Twigg replaced his spectacles, looked up at Hawkwood and blinked myopically. His gaze turned towards the open door of the tavern and the corner of his mouth twitched.

Hawkwood patted the little man’s shoulder. “It’s all right, Ezra. I’ll see you back at the Shop.”

Without waiting for a response, Hawkwood turned and walked away. He did not look back. Had he done so, he would have seen the bowed figure of Ezra Twigg hurrying briskly towards the tavern door, the spring in the clerk’s step matched only by the broad smile on his lips and the twinkle in his eye.

Shadows were lengthening as Hawkwood picked his way through the chain of courts and alleyways.

The few street lamps that did exist were barely adequate, and small deterrent to footpads who continued to stalk the darkened thoroughfares with impunity. Even in broad daylight, it was almost impossible to walk the streets without being propositioned or relieved of one’s belongings. For the unwary pedestrian, dusk only brought added risk. A few gas lamps had been installed in the West End but they were the exception, not the rule. For the most part, night-time London was a world of near impenetrable darkness, fraught with hidden dangers, where even police foot patrols and watchmen feared to tread.

Hawkwood, however, walked with confidence. His presence was acknowledged, but there were no attempts to impede his progress. There was something about the way he carried himself that caused other men to step aside. The scar on his face only added to the aura of menace that emanated from his purposeful stride.

Not that Hawkwood was immune to his surroundings. It was merely that he was hardened to them. He could not afford to be otherwise. London was a fertile breeding ground for every vice known to man. As a Bow Street Runner, Hawkwood had seen more of the city’s dark underbelly than he cared to recall. The shadowy, refuse-strewn byways held precious few surprises, but nevertheless he remained alert as he continued on towards his appointment.

3 (#ulink_179358ea-fb3e-5272-a96d-4467db8d4129)

“So,” Fitzhugh said, “our Samaritan – who was he?”

The two officers were seated in a candlelit alcove in the Blind Fiddler. The fight had attracted a lot of extra custom and the tavern was doing brisk business. Both men were drinking Spanish brandy.

Lawrence pursed his lips. “Well, the pedlar was right, Fitz. Our friend Hawkwood’s certainly not a man to be trifled with.”

Lawrence gazed into his drink, remembering. “Four years ago, it’d be … The Americas. We were part of Sam Auchmuty’s expedition, sent to reinforce Beresford.” Lawrence smiled grimly. “We were fighting the damned Spaniards then. Now they’re our allies. Who’d have thought it?”

It had been before Fitzhugh’s time. A misconceived and ill-fated attempt to liberate South American colonies from Spanish rule. The first wave of troops under the command of Brigadier-General William Carr Beresford had achieved some initial success by taking Buenos Aires, at which point disaster had struck.

Lawrence winced at the memory. “Turned out we weren’t reinforcing Beresford, we were rescuing the silly sod! By the time we got there, the Spanish had regrouped and recaptured the city, and Beresford along with it!”

Lawrence leaned forward, warming to his story. “Now, old Sam knew that if we were to stand any chance of getting to Beresford we’d have to take Montevideo first, as a bargaining tool. Which we did, but by God they gave us a fight! The bastards were waiting for us on the beach. We forced ‘em back, of course. Then found they’d fortified the bloody place, so we had to lay siege. Bombarded them with the ships’ twenty-four-pounders. Took us four days before we finally secured the breach.”

Lawrence’s voice trailed off. Fitzhugh realized that the major was holding the watch. The cover was open and Lawrence was fondling it abstractedly, running his thumb across the engraved surface. He looked up, recovered himself, slipped the timepiece back into his sash and continued. “Lost a lot of good men before they surrendered. Took a host of prisoners, too, including the governor, Don Pasquil. But there was one fellow, a general he was, in command of the citadel. Can’t remember his blasted name. Refused to give himself up. Auchmuty sent a flag of truce promising safe passage, but he declined the offer. So Sam ordered in the sharpshooters.”

Fitzhugh’s eyed widened. “Sharpshooters?”

“We had a detachment of the 95th with us. A brace of their riflemen were ordered to a nearby tower with orders to pick this general out and shoot him dead. I was directed to assist. Our friend was one of the riflemen. A lieutenant he was. Didn’t know his name then, though I recall thinking it strange that they should have sent an officer to do the job.”

Fitzhugh frowned. “How can you be sure it was the same fellow?”

“Because of what I witnessed that day. It’s not something I’m likely to forget. We were atop the tower, the riflemen, myself and a couple of privates, waiting for the general to put in an appearance. Sure enough, out he came, up at his ramparts, strutting around in his frills and finery, proud as a turkey cock.”

The major reached inside his jacket and extracted a short-stemmed clay pipe and a leather tobacco pouch. With what seemed to Fitzhugh like maddening deliberation, Lawrence packed the pipe and returned the pouch to his jacket. Fitzhugh watched in frustrated silence as Lawrence lit a taper from the candle on the table and held the flame to the pipe bowl. When the tobacco was glowing to his satisfaction, Lawrence extinguished the taper with his thumb and forefinger and returned it to the container by his elbow. At first Fitzhugh suspected the major was toying with him, prolonging the agony. Then he realized that Lawrence was using the opportunity to collect his thoughts.

The major sucked noisily on the pipe stem. “Never saw anything like it, Fitz. Our friend stands there, looking out over the rooftops towards the general’s position. Doesn’t say a word, just stares. Then, calm as you like, he takes up his rifle, loads it, rests it on the parapet, and takes aim.

“One shot, Fitz, that’s all it took. I was watching the general through my glass. The bullet took the bugger in the head. Blew his brains out.”

“What was the range?”

“Two hundred and twenty yards, if it was an inch.”

“Good God!” Fitzhugh’s jaw dropped.

“Best damned shooting I’ve ever seen.”

“I can believe it,” Fitzhugh said, marvelling.

“Did the trick, of course. Spaniards surrendered almost immediately.”

“And the rifleman?”

“Returned to his unit. Never saw him again. Never forgot that shooting, though. Quite outstanding.” Lawrence fell silent, lost in a quiet moment of reflection. He drew on his pipe, then lifted his mug and drained the contents.

“Another?” Fitzhugh asked.

Lawrence stared down at his mug, as if noticing for the first time that he had emptied it. “Why not?”

Fitzhugh raised his hand and beckoned to one of the serving girls. At the summons of a handsome young man in uniform, she approached the table with a ready grin. Rounded breasts strained against her low-cut bodice as she bent forward and retrieved the empty mugs. Fitzhugh gave his order and the girl pulled away, her left breast pressing heavily against his arm, reminding the lieutenant of his and Lawrence’s plans for the evening: a visit to a small and very discreet establishment off Covent Garden, in which hand-picked young ladies of beauty and charm provided entertainment of a kind not found in the Officers’ Mess.

Fitzhugh watched the girl depart, following her passage through the gauntlet of roving hands and lewd enticements. A thought occurred to him and he turned back to Lawrence.

“Why do you think he denied having met you before?”

Lawrence shrugged. “Hard to say, though he has less cause to remember me than I do him.”

Not strictly true. The major was being modest. Fitzhugh knew for a fact that Lawrence’s contribution to the taking of Montevideo had been considerable. The watch that the major prized so highly was testament to the fact. It was a part of regimental lore handed down to junior officers.

The British had laid siege to the city’s Spanish fortifications using tried and tested means, albeit medieval in conception. They had constructed batteries and breastworks, gabions and fascines to protect the guns brought up from the men-of-war that had transported them from Rio de Janeiro.

The walls of the city were six feet thick. As Lawrence had said, it had indeed taken four days for the cannon to knock down the gates. The British troops had attacked in the early morning, under cover of darkness. The forlorn hope, the forward troops charged with leading the frontal assault, had been led by a Captain Renny. When Renny had been felled by a Spanish musket ball, it had been the young Lieutenant Lawrence who had, quite literally, stepped into the breach and pressed home the attack, leading his men across the wall and on into the town.

Sir Samuel Auchmuty had presented Lawrence with the watch, his own timepiece, as a measure of his regard for his junior officer’s bravery. As further reward, Lawrence had also received his captaincy, courtesy of the late, lamented Renny.

The girl returned bearing their drinks. Another smile for Fitzhugh and she was gone, with perhaps just a slight exaggeration in the sway of her broad hips.

“Damned curious change of career,” Fitzhugh mused, taking a sip from his freshly filled mug. “Rifleman to Runner.”

“And a damned efficient one would be my guess,” Lawrence responded, adding ruminatively, “though I doubt it’s gained him too many friends.”

Before the lieutenant could query that observation, the major rose to his feet and drained his mug. Tapping his pipe bowl against the table leg, Lawrence grinned at his lieutenant’s expression. “Come now, young Fitz, drink up. It’s time you and I took a stroll. The way that serving girl’s been giving you the glad eye reminds me we’ve to keep our appointment at Mistress Flanaghan’s. Seeing the dumplings on that young wench has done wonders for my appetite!” Without waiting for a response, the major stowed his pipe, reached for his shako and started for the tavern door.

Realizing he was about to get left behind, Fitzhugh gulped down his brandy and followed suit.

As the two officers emerged on to the darkening street, Lawrence’s thoughts returned to the encounter in the tavern yard. There was certainly more he could have told Fitzhugh about the taciturn ex-rifleman; a lot more, as the lieutenant probably suspected, following their hasty departure. But there had been something in Hawkwood’s eye that had caused Lawrence to stay his hand. It had been clear, from their exchange, that there was a reluctance on Hawkwood’s part to revisit the past. Absently, the major’s hand reached for his watch chain. Reassuring himself that the timepiece was intact and in place, the major breathed an inner sigh of relief. And a man’s past was his own affair. Hawkwood could disappear back into the obscurity he obviously preferred. As for young Fitzhugh, well, the lieutenant would have to remain in blissful ignorance.

Lawrence traced the watch casing with his thumb. I owe Hawkwood at least that much, he thought.

The early evening crowds were beginning to gather as Hawkwood made his way along Bow Street. Theatre-goers mingled beneath the wide portico of Rich’s Theatre, while others wended their way towards the Lyceum and the Aldwych. The coffee shops, gin parlours, brothels and taverns that were housed within and around Covent Garden were already full to overflowing, and the bloods, pimps and molls who frequented the area were out in force. The jangle of horse-drawn carriages added to the general noise and bustle. From somewhere within the mêlée arose the grinding strains of a barrel organ.

Number 4 Bow Street was a narrow, five-storeyed town house with a plain façade. Save for the extra floor, there was little to distinguish the building from the adjoining architecture. It was the room at the rear of the ground floor, however, that gave the place its name. To those who toiled within its confines, it was referred to as “The Shop”. To the rest of the city’s inhabitants it was known as the Public Office.

Hawkwood pushed his way through the handful of loiterers camped on the front step and entered the open doorway. A narrow passage ran towards the back of the building. Hawkwood’s boots echoed hollowly on the wooden floor.

The offices were not yet closed for the day. Studious, whey-faced clerks laden with paperwork, scuttled along candlelit corridors. In the Public Office itself, a late court was in session. The room was crowded. Seated at the bench, the presiding magistrate gazed out over the proceedings with a look of resigned boredom on his puritanical face.

Hawkwood removed his riding coat and ascended the stairs to the first floor and the Chief Magistrate’s private chambers. Hawkwood laid his coat across the back of a chair, walked across to the door and knocked once.

“Come!” The order was given brusquely.

The room was square and oak panelled. Several portraits lined the walls. They showed dour, waxen-faced men in sombre dress; previous occupants of the office. A desk filled the space in front of the high, curtained windows. A large fireplace, flanked by a matching pair of high-backed, heavily upholstered chairs, stood against the wall to Hawkwood’s left. Logs were burning brightly in the grate. A long-cased clock stood guard in the corner. Its hypnotic ticking added to the air of solemnity.

The silver-haired man seated at the desk did not acknowledge Hawkwood’s entrance but continued writing, the scratch of nib on paper tortuous in the still, quiet room.

Hawkwood waited.

Eventually, the man at the desk looked up. He placed the pen in the inkstand, straightened his papers and gazed at Hawkwood for several moments. “The operation against the Gant woman went well, I trust?”

“Better than I’d expected,” Hawkwood said.

The news was received with a frown.

“I didn’t think we’d get close enough to catch her, but she hadn’t bothered to post lookouts. She must be getting careless in her old age.”

The silver-haired man pondered the significance of the statement. “She’s in custody?”

“She and her lackwit son. They’re in the cells across the road.”

Curiously, the Bow Street Public Office did not possess facilities for detaining felons. A long-standing arrangement was in force by which the landlord of the Brown Bear pub on the opposite side of the street was paid a nominal sum to provide special strong-rooms that could be used as holding cells.

The silver-haired man nodded in quiet satisfaction. “Excellent. They’ll be dealt with in the morning. They gave you no trouble?”

Hawkwood thought about the knife tear in his coat. “Nothing I couldn’t handle.”

“And the children?”

“I gave the constable instructions to send them to Bridewell.”

“From where, no doubt, they will abscond with ease.”

The silver-haired man sighed, placed his palms on the desk and pushed himself upright. His movements were unhurried and precise.

James Read had held the office of Chief Magistrate for five years. He was of late middle age, with an aquiline face, accentuated by the swept-back hair. A conservative dresser, as befitted his station, his fastidious appearance was deceptive, for there were often occasions when he displayed a quite dry, if not mordant, sense of humour. Read was the latest in a long line of dedicated men. One factor, however, set him apart from those who had gone before. Unlike his illustrious predecessors, and whether as a measure of his indifference or as a throwback to a lowly Methodist upbringing, James Read had refused the knighthood which the post of Chief Magistrate traditionally carried.

Read walked across the room, stood in front of the fire, his back to the flames, and lifted his coat-tails. “This damned house is like a barn. Nearly midsummer and I’m frozen to the bone.”

He studied Hawkwood without speaking, taking in the unfashionable long hair, and the strong, almost arrogant features. Shadows thrown by the flickering firelight moved across Hawkwood’s scarred face. A cruel face, Read thought, with those dark, brooding eyes, and yet one which women probably found compellingly attractive.

“I have another assignment for you,” Read said, his face suddenly serious. He adjusted his dress and stepped away from the fire. “Last evening there was an attack on a coach. Two people were killed: the guard and one of the passengers.”

“Where?”

“North of Camberwell. The Kent Road.”

Hawkwood knew the area. Wooded heath and meadowland, and a well-known haunt of highwaymen. Of late, attacks had been few and far between; a result of the reintroduced horse patrols, bands of heavily armed riders, mostly ex-cavalry men, who guarded the major routes in and out of the capital.

“What was the haul?”

“Money and valuables; perhaps fifty guineas’ worth. They were very thorough.”

Hawkwood looked up. “They?”

“A man and a boy, judging from the accounts of the witnesses.” Read gave a short, bitter laugh. “Master and apprentice.”

The magistrate reached into his pocket and extracted a small, oval snuffbox. With practised dexterity, he flicked open the mother-of-pearl lid and placed a pinch of snuff on the juncture between the thumb and forefinger of his left hand. He inhaled the fine powder through his left nostril. Repeating the procedure with his right, he closed the box and tucked it away.

“Any descriptions?” Hawkwood knew the answer to that question. A shake of the Chief Magistrate’s head confirmed his suspicion.

The Magistrate wrinkled his nose. As he did so, he removed a silk handkerchief from his sleeve.

“Both were masked. It was the older man who did all the talking. It’s possible the boy was a mute. They are, however, both murderers. ‘Twas the older man who killed the courier. The –”

“Courier?” Hawkwood interjected.

“An admiralty courier. He joined the coach at Dover. The guard was shot by the accomplice. This is a pair of callous rogues, Hawkwood, make no mistake.”

“Anything else?”

Hawkwood winced as the Chief Magistrate let go a loud sneeze. It took a moment for Read to recover. Pausing to wipe his nose with the handkerchief, the Chief Magistrate shook his head once more. “Nothing substantial. Though there was one rather curious observation. The surviving passengers had got the impression that the older man was not much of a horseman.”

“How’s that?”

“In the course of the robbery, they were surprised by a mounted patrol. In his haste to make an escape, the fellow very nearly took a tumble. Managed to hang on to his nag more by luck than judgement, apparently.”

“A highwayman with no horse sense,” Hawkwood mused. “There’s an interesting combination.”

“Quite so,” Read sniffed. “Though I don’t suppose it means anything. Still, it was a pity. Had Officer Lomax and his patrol arrived a few minutes earlier they might well have caught them. As it was, the villains got clean away. It was a foul night. The rain covered their tracks.”

“A man and boy,” Hawkwood reflected. “Not much to go on.”

Read stuffed the handkerchief back up his sleeve. “I agree. Which is why I’ve sent for you. We’ll leave Lomax to deal with the passengers. I suggest you concentrate on the items that were stolen. Tracing their whereabouts could be the only way to find the culprits. You have unique contacts. Put them to good use. Murder and mutilation on the king’s highway – I’ll not have it! Especially when it involves an official messenger! And I understand the coachman, poor fellow, leaves a widow and four children. By God, I want these men caught, Hawkwood. I want them apprehended and punished. I –” The Chief Magistrate caught the look on Hawkwood’s face.

“Mutilation?” Hawkwood said.

The Chief Magistrate looked down at his shoes. Hawkwood followed his gaze. James Read, he noticed, not for the first time, had very small feet; delicate, dancer’s feet.

“The courier’s arm was severed.”

A knot formed itself slowly in Hawkwood’s stomach.

“They cut off his arm?”

“He was carrying a dispatch pouch. The robbers were obviously of the opinion that it held something of value. When the courier refused to give it up, he was shot and the pouch was taken. The other passengers said he refused to hand over the key. The horse patrol was almost upon them. The robbers panicked.”

“And did the pouch contain anything of value?”

The Chief Magistrate waved his hand dismissively. “Certainly nothing that would interest a pair of common thieves. They probably tossed it away at their first halt. It was the money and jewels they were after. Easily disposable, and the means by which we may precipitate their downfall.”

“I’ll need a description of the stolen goods.”