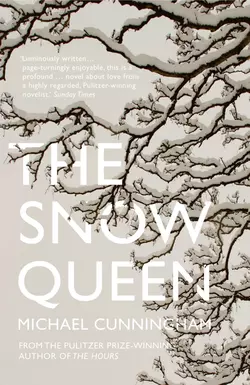

The Snow Queen

Michael Cunningham

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 650.01 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ‘Luminously written … page-turningly enjoyable, this is a profound novel about love from a highly regarded, Pulitzer-winning novelist’ Sunday TimesIt’s November 2004. Barrett Meeks, having lost love yet again, is walking through Central Park when he is suddenly and inexplicably inspired to look up at the sky, where he sees a pale, translucent light that seems to regard him in a distinctly godlike way. Although Barrett doesn’t believe in visions – or in god, for that matter – he can’t deny what he’s seen.At the same time, in the not-quite-gentrified Bushwick neighborhood of Brooklyn, Beth, who’s engaged to Barrett’s older brother ,Tyler, is dying of colon cancer. Beth, Tyler, and Barrett have cobbled together a more or less happy home. Tyler, a struggling musician with a drug problem, is trying and failing to write a wedding song for his wife-to-be – something that will be not merely a sentimental ballad but an enduring expression of eternal love.Barrett, haunted by the light, turns unexpectedly to religion. Tyler grows increasingly convinced that only drugs can release his deepest creative powers. Beth tries to face mortality with as much courage and stoicism as she can summon.Cunningham follows the Meeks brothers as each turns down a decidedly different path in his search for transcendence. In subtle, lucid prose, he demonstrates a profound empathy for his conflicted characters and a singular understanding of what lies at the depth of the human soul.‘The Snow Queen’, beautiful and heartbreaking, comic and tragic, proves once again that Cunningham is one of the great novelists of this generation.