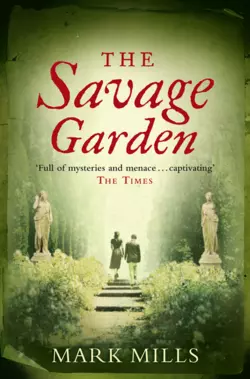

The Savage Garden

Mark Mills

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 766.24 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The No.1 bestselling novel and Richard & Judy Summer Read: a haunting tale of murder, love and lost innocence for fans of Carlos Ruiz Zafon and Jed RubenfeldBehind a villa in the heart of Tuscany lies a Renaissance garden of enchanting beauty. Its grottoes, pagan statues and classical inscriptions seem to have a secret life of their own – and a secret message, too, for those with eyes to read it.Young scholar Adam Strickland is just such a person. Arriving in 1958, he finds the Docci family, their house and the unique garden as seductive as each other. But post-War Italy is still a strange, even dangerous place, and the Doccis have some dark skeletons hidden away which Adam finds himself compelled to investigate.Before this mysterious and beautiful summer ends, Adam will uncover two stories of love, revenge and murder, separated by 400 years… but is another tragedy about to be added to the villa′s cursed past?