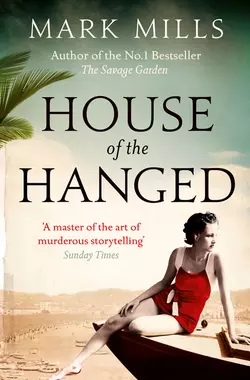

House of the Hanged

Mark Mills

From the No. 1 bestseller and author of Richard & Judy pick The Savage Garden: a riveting tale of passion and murder set on the French Riviera in the 1930s for fans of Carlos Ruiz Zafon and Jed RubenfeldFrance, 1935: At the poor man’s end of the Riviera sits Le Rayol, a haven for artists, expatriates and refugees. Here, a world away from the rumblings of a continent heading towards war, Tom Nash has rebuilt his life after a turbulent career in the Secret Intelligence Service.His past, though, is less willing to leave him behind. When a midnight intruder tries to kill him, Tom knows it is just a matter of time before another assassination attempt is made.Gathered at Le Rayol for the summer months are all those he holds most dear, including his beloved goddaughter Lucy. Reluctantly, Tom comes to believe that one of them must have betrayed him. If he is to live, Tom must draw his enemy out, but at what cost to himself and the people he loves…?

HOUSE OF

THE HANGED

MARK MILLS

For my mother

Man is neither angel nor beast; and the misfortune is that he who would act the angel acts the beast.

Blaise Pascal (1623–1662)

Contents

Cover (#uf711a2b2-58d5-53f2-8313-81786729446d)

Title Page (#u9fa493ed-12f8-5f1e-b526-3c0a905ad181)

Epigraph (#u5b5b2659-4017-5c29-bd41-fe59aba30232)

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Acknowledgements

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Mark Mills

Copyright

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One

Petrograd, Russia. January 1919

The moment the guard called her name she felt the weight of the other women’s eyes upon her.

It didn’t make sense, didn’t fit with the grim clock that regulated their lives. Too late in the day for an interrogation, the usual hour of execution was still some way off.

‘Irina Bibikov,’ snapped the guard once more, his silhouette black against the open door of the darkened cell.

She was hunched on her pallet bed, her back against the wall, her knees pulled tight to her chest for warmth, as tight as her new belly would permit. Unwinding, she rose awkwardly to her feet, her palm pressed to the damp stonework for support.

The guard stepped away from the door. She knew better than to meet his gaze as she passed by him and out into the corridor.

Blinking back the ice-white light from the bare electric bulb, she briefly heard the murmur of prayers on her behalf before the guard pulled the steel door shut behind them.

Tom fought the urge to hurry ahead. Nothing to arouse suspicion, he told himself. His papers, though false, were in good order, good enough to pass close scrutiny. He knew this because he’d been stopped by a Cheka patrol earlier that day while crossing Souvorov Square.

There had been two of them, small men in shapeless greatcoats that reached almost to their ankles, and they had enjoyed their authority over Yegor Sidorenko. The name was Ukrainian, to account for the faint but un disguisable hitch in Tom’s accent. He had called them ‘Comrade’; they had called him ‘Ukrainian dog’ before sending him on his way. More than a year had passed since the Bolshevik coup, but evidently the spirit of brotherhood so widely trumpeted by Lenin, Zinoviev and the others had yet to reach the ears of their Secret Police. So much for lofty ideals. So much for the Revolution.

Tom knew that he couldn’t bank on being quite so lucky if stopped again, but only as he drew level with No.2 Gorokhovaya did it occur to him that he might actually find himself face-to-face with the same two Chekists as they entered or left their headquarters.

There were patrols coming and going, passing beneath the high, arched gateway punched in the drab façade. Beyond lay the central courtyard, where the executions took place, where the bodies were loaded into the back of trucks, their next stop, their terminus, some nameless hole hacked out of the iron-hard ground beyond the city limits.

At least the sharp north wind sluicing the streets of the Russian capital permitted him to draw his scarf up over his nose, all but concealing his face. As he did so, he cast a furtive glance through the archway, past the sentries shivering at their posts.

What was he looking for? Signs of unusual activity, some indication that the plan had already been compromised. He saw nothing of note, just a courtyard shrouded in the gathering gloom, and the dim outlines of men and vehicles.

Trudging on past through the deep snow, Tom silently cursed the fact that Irina hadn’t been transferred by now to one of the state prisons, Shpalernaya or Deriabinskaya, where security was considerably more lax and bribery endemic. Instead, his only option had been to try and spring her from the beast’s lair.

It was a cellar room, small and all but empty. There were some mops poking from their pails in one corner and a few large tins of cleaning fluid stacked up in another, but Irina’s eye was drawn to the wooden stool standing alone in the middle of the room. On it were some clothes, neatly folded, with two pieces of paper resting on top.

One was a visitor’s pass made out to Anna Constantinov. On the second was scrawled: St Isaac’s Cathedral. The words were in English, and she recognized the handwriting.

‘Quick,’ said the guard. He was the youngest of the three who oversaw the female prisoners, not much more than a boy, his moustache a tragic overture to manhood. ‘Get changed.’

Irina stared at the slip of paper in her hand, not quite believing that it had happened, trying to picture what Tom must have put himself through, the dangers he had faced, the border crossing from Finland . . .

It was almost inconceivable.

‘Hurry,’ hissed the guard.

His ear was pressed to the door, but his eyes remained fixed on her – eager young eyes, hoping for a glimpse of female flesh.

She was happy to oblige. It might provide some scrap of comfort at the end of his short life. She wondered how much money he’d been promised. More than enough to see him safely away, out of the country. To stay would mean certain death before a firing squad. She looked down at her belly, the still unfamiliar bow, the tautness of the pale skin around her navel.

Dressed now, her soiled clothes heaped on the floor at her feet, she wrapped the shawl around her head and turned to the guard.

‘I’ll get rid of that,’ he said, taking the piece of paper from her.

Young, yet sensible. It wouldn’t be wise to have details of the rendezvous about her person if she was stopped while trying to leave.

‘Good luck,’ he said.

‘You too.’

They parted company wordlessly in the corridor outside, the guard pointing out her route before vanishing into the darkened bowels of the building.

Irina passed by the steps leading up to the interrogation rooms, silent at this hour, making for the stone staircase at the end of the corridor.

She was curious to see how far she would get.

On the floor above, she ran a short gauntlet of offices flanking a corridor before finding herself in the main lobby. There was a guard on duty at the big desk by the doors, bent over some paperwork. When she stopped to show her pass he waved her on, almost irritably, and she wondered if he too was in on it.

Outside in the gloomy courtyard, no one paid her a blind bit of notice, not the troops huddled around the brazier, not the officer berating the two mechanics poking around in the engine of a canvas-covered truck.

Was it really that simple? A mere slip of paper?

There were still the sentries at the main gate to get past, but she could see freedom looming ever larger beyond the tall archway as she approached. A quick glance over her shoulder confirmed that she wasn’t being followed.

One of the sentries unshouldered his rifle, keeping a close watch on her while the other checked her pass against a ledger in the small cubbyhole which served as their guardhouse. A bitter blast whistled through the archway, stinging her eyes. Then suddenly everything was in order. The pass disappeared into a drawer. Anna Constantinov was free to go.

How had Tom done it? No one had really expected him to try, let alone pull it off, least of all her.

She thrust her hands deep into her pockets and set off up the street, not quite sure what to think, what to do. She needed time to work it through in her head.

She had taken no more than a dozen tentative steps along the icy pavement when she felt a hand land on her shoulder and heard the teasing drawl of a familiar voice close to her ear.

‘Going somewhere, Irina?’

Tom lit another candle, an excuse to stretch his legs and warm his fingers over the bank of flickering flames.

He had spent more than an hour in the Alexander Nevsky Chapel, most of it on his knees, head bowed in a show of prayer. A pew would have been nice, a stool, anything, but seating had never figured large in the thinking of the Russian Orthodox Church. It allowed them to cram the people in. Fourteen thousand souls could fit into St Isaac’s Cathedral; at least, that’s what Irina had told him when she had first taken him there, soon after his arrival in Petrograd, his raven-haired tour guide skipping her classes at the Conservatoire to show him some of the sights.

It had been a bright June morning, the sunlight flashing off the vast gilded dome and laying bare the fussy opulence of the interior: the intricate patterning of the marble floor, the steps of polished jasper, the columns of green malachite and blue lazurite, the walls inlaid with porphyry and gemstones, and the gilded stucco and statues wherever you turned. A blaze of fragmented colour, had been Tom’s first impression, like stepping inside a child’s kaleidoscope.

He had made the right noises, but Irina had read his thoughts, sensed his reservations.

His church, the church of his youth, was a humble ivy-tangled affair in a village on the outskirts of Norwich, where the damp rose in waves around the bare plaster walls, and where Mr Higginbotham, the churchwarden, had once threatened to resign his post because the new altar frontal sported an embroidered hem. Tom’s father had seen that the offending article was returned to Wippell’s, who had promptly dispatched a suitably chaste replacement.

‘Your father is a priest?’ Irina had asked.

‘A vicar.’

‘Is there a difference?’

‘I suppose not. Only, I’ve never heard my father refer to himself as a priest.’

‘I’m surprised,’ Irina had said, tilting her head at him.

‘What, I give off an unholy glow?’

It was the first time he had seen her laugh, and he could still recall how his heart had soared at the sight of it.

How had they gone from that to this in little more than six months?

He knew the answer, of course. A few weeks after that first visit to St Isaac’s, Tsar Nicholas and the Imperial family had been murdered, slain by the Bolsheviks (in the basement of a house in Ekaterinburg, if the intelligence report which had recently passed through his hands in Helsinki was to be believed). The real turning point, though, had been the attempt on Lenin’s life at the end of August – two bullets, one to the chest, one to the neck – as the leader of the Bolsheviks was leaving a rally in Moscow. No one had expected Lenin to survive, but even before it became clear that he would, the Red Terror had been unleashed: a brutal crackdown intended to turn back the rising tide of anti-Bolshevism in the country.

Suspecting British involvement in the assassination plot, the Cheka had stormed the embassy in Petrograd. It was a Saturday, and Tom hadn’t been in the building at the time, but Yuri, the porter, had been. It was Yuri who had searched Tom out at the English Club and described to him the death of Captain Cromie, chief of the Naval Intelligence Department, dispatched with a bullet to the back of the skull after a fierce firefight on the main staircase. Tom’s boss, Bruce Lockhart, head of the special British diplomatic mission to Russia, had been taken into custody, and the Cheka had issued a warrant for Tom’s arrest.

Yuri had been accompanied by a tall and taciturn Finn assigned to spirit Tom away that same evening. In spite of Tom’s protestations, the Finn had not allowed him to see Irina before leaving. Evil was in the air. And besides, there was no time. The last train from Okhta station left at seven o’clock.

Tom’s short summer in the Russian capital had ended abruptly with that journey northwards: by rail to Grusino in a boxcar crammed with silent refugees, then a sapping foot march through the forests and bogs, dodging the patrols, tormented every weary step of the way by thoughts of the woman he had been forced to leave behind. Even when they had slipped past the border post on their bellies into Finland and freedom he had experienced no sense of elation.

The dread prospect of repeating that same perilous journey – not only in the dead of winter, but with Irina in tow – brought Tom out of his reverie.

His eyes darted to the bag of clothes he had secreted in the corner of the chapel, just beyond the glow of the candles. He couldn’t make it out in the shadows, but he sensed that it was there, just as he sensed the presence of someone standing behind him.

His head snapped round expectantly.

It wasn’t Irina; it was a young priest, not much older than Tom, and yet there was something haggard and careworn about him.

‘If He hasn’t heard you by now, then I doubt He’s listening.’

Tom returned the faint smile, but said nothing.

‘Bad times.’

‘Yes, Father.’

‘Vade in pacem,’ the priest said softly before retiring into the gloom shrouding the main body of the cathedral.

Maybe it was the young priest’s depleted air, but Tom felt a sudden shiver of unease pass through him. He now noticed that some of the icons were missing from the walls of the chapel. Stolen, or removed for their own protection? Either way, their absence pointed to an ominous shift in the natural order of things. A story blew into his mind, something Irina had once told him. She had been present when two hundred victims of the so-called ‘Bloodless Revolution’ had been laid to rest on the Champ de Mars. Apparently, no crosses had been carried in the procession, and no priests had been allowed to officiate at the burials.

Irina. Was she trying to tell him something? He would normally have dismissed such a thought as superstitious claptrap, but by now the fear had lodged itself in his chest. Why had he even chosen St Isaac’s? Because it was safe? Nowhere was safe in the new Russia. There was certainly no place for obsolete notions of religious sanctuary.

He was a fool. At the very least, he should have remained outside the cathedral, whose thick walls rising into the darkness were beginning to feel more like those of a prison than a place of worship. Even the mosaic saints set in the marble iconostasis towering before him seemed to look down on him now with a certain disapproval, reproaching him for his stupidity.

He hurried over and recovered the bag from the shadows. The park directly across from the north portal would give him a view down Admiralty Prospekt of Irina approaching. More importantly, he would be able to see if she was being followed. He refused to consider the possibility that she wouldn’t show at all. If the mission had failed, there would be no second chances.

He was ten yards shy of the north doors when he saw them enter the cathedral directly in front of him. They weren’t in uniform, they didn’t need to be. The way they were moving, the arrogant purpose in their step, marked the pair out as Chekists. Tom’s instinct was to turn and flee, but he knew they would have the south and west doors covered by now.

Extending an upturned hand, he carried on towards the two men.

‘A few roubles, comrades,’ he pleaded pathetically, ‘for a veteran of Tannenberg.’

Mention of the bloody battle didn’t curry any sympathy.

‘Papers,’ snapped the smaller of the two Chekists.

‘I haven’t eaten in days.’

Not so far from the truth, but Tom found his hand slapped aside.

‘Papers!’

‘Leave him,’ growled the other. ‘You heard what Zakharov said – he has a beard.’

Zakharov. There was no time to process this news – or to give thanks for the last-minute precaution of changing his appearance – as two more men bowled into the building through the north doors. They were wearing leather jackets crossed with cartridge belts. The taller of the two Chekists turned to them.

‘Neratov, you guard the door.’

Any suspicions that Neratov might have had of Tom were dispelled when the smaller Chekist shoved him dismissively aside. The scruffy man with the bag in his hand had evidently been checked and cleared. While the three other policemen fanned out into the cathedral Tom crept sheepishly past the glowering Neratov and out through the doors.

In his haste to put the danger behind him, he slipped on the icy steps leading down from the pillared portico. Falling hard, he felt something go in his wrist. He bit back a cry, not wishing to draw attention to himself.

He glanced up and down Admiralty Prospekt: the pavements were deserted, just an isvochik heading towards him, drawn by a shaggy white horse. It was free, and Tom waved it down, almost laughing at the absurdity of his good fortune.

The coachman, muffled in furs, was bringing the small sledge to a halt when Tom heard the shout.

‘Stop him!’

It came from the cathedral. The tall Chekist stood dwarfed between two pillars of the north portico, waving furiously.

‘Stop him!’ he bellowed again. ‘He’s an enemy of the Soviet!’

With a flick of the driver’s reins the sleigh took off. Tom stumbled after it, unable to get any meaningful purchase on the compacted snow, falling quickly behind as the horse’s trot became a canter. Realizing the futility of the pursuit, he cut left across the street and disappeared into the park on the far side.

Overhead, a half-moon hung in a cloudless sky, and even beyond the pool of light thrown by the street lamp he could still pick a route with ease. Unfortunately, this also meant that his pursuers would have no trouble following his deep tracks in the snow.

That first lone shout had now become a chorus at his back. Outnumbered, the only thing he had in his favour was that he had prepared himself for such conditions. The snow in the park was deep, thigh-deep in places, just as it had been in Finland. Before leaving Helsinki, he had trained hard in anticipation of their flight from Russia, pushing himself on occasions to almost masochistic extremes. Not only was he in better physical condition than he’d ever been, but he had also accustomed himself to the hunger and the cold until his mother would barely have recognized the lean, gaunt spectre of her own son before her. He had grown a beard, and he had learned to stoop convincingly, knocking a few inches off his height, making him one of the crowd.

‘Come on, you bastards,’ Tom muttered to himself. ‘Let’s see what you’ve got.’

What they had, it turned out, was guns. And they weren’t afraid to use them.

The first few shots ripped through the skeletal branches above his head. He assumed they were warning shots until he heard something whistle past his left ear, death missing him by a matter of inches.

Crouching, he drove his legs on, knowing that every hard yard gained now would equate to three or four when the snow-bound park gave way to Admiralty Quay. He lost a little of his advantage when he was suddenly pitched forward into the snow, as if shoved hard in the back by a phantom hand. Scrabbling to his feet, he figured the bullet must have struck the bag slung over his shoulder, embedding itself in the jumble of clothing he’d put together for Irina.

A primeval impulse to survive, to live beyond his twenty-two years, took complete possession of him now. He ploughed on like a man sprinting through a waist-high sea to save a drowning child. Pleasingly, the shouts of his pursuers had dimmed almost to silence by the time he finally broke free on to Admiralty Quay.

He knew that the frozen stillness of the river lay just beyond the low wall ahead of him. Should he risk it, skittering across the ice, out in the open? No. He bore left, away from the Admiralty building, his legs burning, but with a lot of life still left in them.

Run, he told himself. Settle your breathing and stretch out your stride. He would take the next street on the left, head south, lose himself in the back streets around the Mariinsky Theatre.

Tom glimpsed the revolver in the other man’s hand a split-second before they collided. Both had been slowing to make the turn, but the head-on impact still sent them sprawling in a tangle of limbs.

The gun. Where was it? No longer in the man’s hand, but within reach. Tom lashed out with his foot, slamming the heel of his boot into the man’s head, catching him in the temple. This bought him a precious second, enough to give him a fighting chance. The two of them scrabbled and clawed for possession of the weapon, the lancing pain in Tom’s damaged wrist numbed by the panic.

The moment he realized he’d been beaten to the prize, the Cheka man froze. Keeping the revolver trained on him, Tom scrabbled to his feet.

‘Please . . .’ said the man, raising a futile hand to stave off the bullet.

Tom glanced down Admiralty Quay: vague smudges of movement in the distance, drawing closer, but too far off yet to pose a threat.

Tom looked back at the man. He was young, Tom’s age, his lean, handsome face contorted with fear, and in those pitiful eyes Tom saw everyone who had ever been cruel to him, everyone who had ever hurt him, deceived him, betrayed him.

‘Vade in pacem,’ he said quietly.

Go in peace – the same parting words of Latin which the priest had offered to him in the chapel at St Isaac’s just minutes before. He didn’t know why they sprang from his mouth; he didn’t care.

He was gone, disappearing down the darkened street, flying now on adrenaline wings.

The apartment building was a drab five-floored affair on Liteiny Prospekt, near the junction with the Nevsky. The grey morning light didn’t do it any favours.

Tom watched and waited from across the street, one eye out for Cheka patrols, or anyone else showing undue interest in the apartment building. He had got rid of the bag, abandoning it in the coal cellar where he’d passed a sleepless night, swaddled in the clothing intended for Irina. The bullet that had knocked him flat in the park was now in his hip pocket. He had tried to think of it as his lucky charm, but how could it be? If Irina wasn’t dead by now, she would be soon. He was too much of a realist to believe otherwise.

He knew how the Cheka operated; months of tracking their working methods from the safety of Finland had introduced him to the brutal truth. In Kharkov they went in for scalping and hand flaying; in Voronezh they favoured rolling you around in a barrel hammered through with nails. Crucifixion, stoning and impalement were commonplace, and in Orel they liked to pour water over their victims, leaving them to freeze outside overnight into crystal statues.

This is what the Revolution had brought out in men: not the best, but the very worst, the stuff of bygone eras, when Genghis Kahn and his blood-thirsty hordes had run merry riot through the Steppes.

In no way could Tom be held accountable for the dark state of nature that lurked in men, but he was to blame for choosing to gamble with it, and losing. How would things have turned out for Irina if he hadn’t tried to intervene? She might have weathered the incarceration, the torture, and been released. What if he had underestimated her? Should he not have had more faith in her resilience?

These were the questions that had kept him awake in the coal cellar, and he couldn’t imagine a time when they wouldn’t plague his thoughts. If he had come here to this grim apartment building on Liteiny Prospekt, it was only with a view to dragging some small consolation from the disaster.

He had a street number and an apartment number, but no name. Markku had told him that the name was of no importance; the one he knew her by was probably false anyway.

‘It’s a woman?’ Tom had enquired.

‘It’s something close,’ had been Markku’s enigmatic reply.

The problem lay in slipping past the concierge un noticed. It was well known that the building caretakers of Petrograd were rapidly becoming the unofficial eyes and ears of the Cheka. It was even rumoured that some made false denunciations of their residents, leaving them free to pillage the apartments once the ‘counter-revolutionaries’ had been carted off.

Seeing an elderly woman rummaging for her key at the entrance door, Tom hurried across the street, arriving as the door was swinging shut behind the woman. He stopped it with his hand, waited a few moments, then slipped inside.

The cavernous entrance hall was dark and deserted. He heard the woman puffing her way up the stone staircase, and through the glazed doors directly ahead of him he could see a man shovelling snow in the courtyard.

The apartment was on the third floor, towards the back of the building. He knocked, and was about to knock again when he heard a female voice.

‘Who is it?’

‘Markku sent me,’ he replied, in Russian.

‘I don’t know anyone called Markku.’

‘He told me to say that you make the best pelmeni in all Russia . . . after his mother’s.’

Three locks were undone before the door was opened as far as the guard chain would permit. A small woman, a shade over five feet, peered up at him defiantly. Her black hair was threaded with silver strands and pulled back tightly off her lined face. Her dark eyes were clear and hard, like polished onyx. They roamed over him from head to toe, then past him, searching the corridor behind. Only then did she release the chain.

Tom followed her along a corridor into a large and extravagantly furnished living room. The rococo divans, Persian rugs and gilt-framed portraits – one of a booted general, another of some high-bosomed ancestress – had obviously been intended for a far nobler space than this; here, they looked awkward and overblown, eager to be elsewhere.

Tom turned and found himself staring into the barrel of a handgun.

‘Take off your coat,’ said the woman. ‘Take it off and throw it on that chair there.’

There was nothing strained or hysterical in her voice. She might just as well have been a doctor inviting him to remove his clothes in a consulting room.

Tom did as she requested, unquestioningly, watching while she searched the coat, knowing what she would find. Her eyes only left his momentarily, to glance down at the revolver as she pulled it from one of the pockets.

‘This is a Cheka weapon,’ she said, levelling her own gun at his head.

Tom cowered. ‘It was. Until last night.’

‘You’re not Russian.’

‘I’m English.’

She switched effortlessly to English, with just the barest hint of an accent. ‘And where were you born?’

‘Norwich.’

‘A flat and dull county, Norfolk.’

‘You obviously don’t know it well.’

‘Sit down. Hands on your knees.’

Tom deposited himself on a divan. The woman remained standing.

‘Who are you?’ she asked.

‘Tom Nash. I was part of the Foreign Office delegation sent over here last summer.’

‘A little young for that sort of thing, aren’t you?’

‘It was my first assignment after joining.’

‘You knew Bruce Lockhart?’

‘Of course, I worked for him here.’

‘Lockhart was lucky to get away with his life.’

‘So was I. It was Markku who got me out of the country after they stormed the embassy.’

‘And how is Markku?’ she demanded flatly.

Tom and the tall Finn had become fast friends since their escape from the capital. They’d had little choice in the matter; the Consulate in Helsinki had lodged them in the same room at the Grand Hotel Fennia.

‘Stuck in Helsinki,’ said Tom. ‘Frustrated. Drunk most of the time.’

‘He’s still one of the best couriers we’ve got. So why, I’m wondering, do they send us a boy from the Foreign Office?’

‘I’m with the Secret Intelligence Service now.’

‘Is that right?’ She made no effort to conceal her scepticism.

‘I was seconded when I got to Helsinki.’

This wasn’t quite true. Tom had pushed for a transfer to the SIS in Helsinki, anything that would keep him close to Petrograd, to Irina. A desk job back in London hadn’t been an option in his own mind, and he had managed to persuade others that his skills as a Russian-speaker would be best served closer to the front line.

‘Prove it,’ said the woman.

‘I can’t.’

‘I suggest you try.’

Tom hesitated before replying. ‘ST-25.’

‘That means nothing to me,’ she shrugged.

But she was lying; he had seen the faint flicker in her obsidian eyes. She knew as well as he did that ST-25 was the codename for the sole remaining SIS agent in Petrograd. The Bolsheviks had brutally broken the American spy network over the autumn, and they were close to achieving the same with the British. The elusive ST-25 remained a thorn in their side, though. The Cheka had even set up a special unit devoted to hunting him down.

‘You want his real name?’ said Tom. ‘I can give it to you if that will help.’

‘She doesn’t need to know my real name.’

The voice was low and steady, and it came from behind Tom.

He turned to see a man of middle height step into the room. It was hard to judge his age – early thirties maybe – the thick dark beard blunting his handsome features showed no signs of grey.

‘Katya, I think our friend here could do with a hot drink . . . and maybe a piece of bread, if you can spare it.’

Katya eyed Tom with all the warmth of an attack dog called to heel by its master. Handing over the two guns, she disappeared into the kitchen.

‘Paul Dukes?’ asked Tom.

Dukes nodded and settled into an armchair. It was a moment before he spoke. ‘What happened to your wrist?’

It was tightly bound with the leather belt he’d brought along for Irina. ‘I think it might be broken.’

Dukes released the barrel of the revolver and checked the cylinder. ‘She’s right,’ he said. ‘Why did Leonard send you?’

Leonard Pike was chief of SIS operations in northern Russia, calling the shots from the embassy in Stockholm. Although Tom had never met him, it was Leonard who had agreed to take him on in Helsinki.

‘He didn’t send me,’ Tom replied. ‘I’m sailing under my own colours.’

Dukes snapped the barrel shut and looked up, intrigued. ‘Go on.’

Tom told him everything: of his relationship with Irina, his forced flight from Russia, and his work for the Secret Intelligence Service in Helsinki, which had involved deciphering many of Dukes’s own intelligence reports. Helsinki was a mess, a sinkhole of desperation and duplicity, swarming with émigrés and spies. Information and disinformation were the twin orders of the day in the Finnish capital, and Tom’s other duties had entailed trawling the city’s restaurants, hotel bars and drawing rooms, keeping an ear out for anything of value.

This wasn’t how he had got wind of Irina’s arrest, though; that news had come to him via Markku, who had heard it from one of the other couriers, along with the small but devastating detail that Irina was pregnant. Tom didn’t reveal this to Dukes, if only because the notion that he’d fathered a child was still too big to grapple with on his own, let alone share with a stranger. Besides, at the time it hadn’t coloured the decision he’d arrived at with Markku’s encouragement and assistance.

Both men knew that Bayliss, the SIS station chief in Helsinki, would never have sanctioned a rescue attempt, so the plan had been hatched in secret, with Markku providing false documents, detailed instructions on a number of routes in and out of the country, as well as the names of a few reliable contacts in Petrograd. The sixty thousand roubles which Markku estimated would be required for bribes had proved much harder to come by. In the end Tom had been left with no other choice but to ‘borrow’ it from the SIS slush fund.

Dukes had been listening attentively throughout, but now broke his silence with the bleak observation, ‘That’s going to cost you your job, and probably a lot more.’

‘I don’t care. It all went wrong last night.’

He described how the band of Chekists had shown up at St Isaac’s Cathedral in place of Irina, and how he had only just managed to slip through their fingers.

Dukes got to his feet and wandered to the fireplace. He poked at a burning log with the toe of his boot. There was something ominous in his studied silence.

‘I’m going to tell you this now,’ he said eventually, turning to face Tom. ‘Because if you don’t hear it from me, you may never hear it at all.’ He paused. ‘She was executed last night.’

Tom felt a cold hand settle on his heart. His words, when they came, sounded distant, hollow.

‘How do you know?’

‘Console yourself with the fact that they would have killed her anyway. You see, I never met her myself, but I know of people she helped. We were aware of her . . . predicament.’

Her predicament? He made her sound like a debutante torn between two evening gowns in Harrods.

‘How do you know?’ demanded Tom, more forcefully this time.

‘I had it on good authority early this morning.’

‘Good authority?’

‘A very reliable source, I’m afraid.’

‘Who?’

‘I can’t say.’

‘I have a right to know.’

‘And I have a duty to protect his identity. If you’re captured by the Cheka they will make you talk. Don’t look so affronted – everyone talks. Do you want him to lose his life too?’

At that moment Katya returned bearing a tray, which she placed on a low side table. She must have been eavesdropping from the kitchen. It wasn’t just the misting of pity in her hard eyes; before pouring the tea she handed Tom two tablets and a glass of water.

‘Aspirin. For your wrist.’

The tea cups matched the antique porcelain pot, and Dukes savoured a first, warming sip before continuing.

‘Look, believe me, I’m sorry. We’ve all lost friends, good friends, and I daresay we stand to lose many more. But you shouldn’t have come here. Markku should not have given you this address. There’s nothing we can do for you.’

‘I didn’t come here for me, I came here for you – to warn you.’

He explained that Markku had put him in contact with a man named Dimitri Zakharov. It was Zakharov who had organized the escape, Zakharov who had betrayed him to the Cheka.

Dukes and Katya exchanged a brief look. ‘I doubt that very much,’ said Dukes. ‘Zakharov gave them a description of me. I overheard them say it.’

Dukes hesitated. ‘If he did, then it was tortured out of him.’

‘He didn’t look too distressed when I saw him leave his apartment an hour ago.’

Dukes was clearly taken aback by this news. ‘Maybe we’re talking about another Zakharov.’

‘How many Zakharovs does Markku know who live on Kazanskaya?’

‘Katya . . .?’

For once she looked shaken. ‘Anything is possible. We both know that.’

Dukes turned his attention back to Tom. ‘I was wrong. You were right to come here.’ He handed the revolver back. ‘I’m surprised there are still six bullets left in the cylinder.’

Tom had indeed trailed Zakharov for a good few streets, imagining the moment – the muzzle of the gun planted at the base of the traitor’s neck, or maybe a swift tap on the shoulder first with the barrel so that Tom could carry with him the flash of recognition, of terror, in the other man’s eyes as a future balm for his soul. In the end, though, he had allowed Zakharov to slip away from him.

Maybe it had been cowardice, the knowledge that retribution would surely come at the cost of his own life, or maybe the calculating pragmatist in him had prevailed over base emotion. Either way, he was alive, and the information he had just handed on might even save lives. It clearly had value; he could see its worth reflected back at him in Dukes’s eyes.

‘This changes everything,’ said Dukes. ‘We can’t stay here. Katya, you also have to leave.’

‘No.’

‘You must.’

‘Not if I don’t know where you’re going.’

‘Katya –’

‘Do I know?’ she insisted.

Dukes shook his head solemnly.

‘Then go,’ she said. ‘Both of you. What are they going to do with an old woman like me?’

Her life had been reduced quite enough already to this: this queer museum of displaced artefacts. The barbarians might be hammering at the gates of the city, but the curator had no intention of abandoning her post.

It took Dukes a few minutes to gather his belongings together, and all the while he was issuing instructions to Tom. Katya accompanied them downstairs as far as the first-floor landing. Pressing something into Dukes’s hand, she said, ‘It was my mother’s.’

Tom also received a parting gift – a jewelled gold locket on a chain.

‘You are a brave boy,’ said Katya, ‘and you deserve to live. But remember . . . keep back one bullet for yourself.’

She shooed them off down the stairs like a mother sending her two sons out to play.

Tom left the building first, turning up his collar and heading south on Liteiny Prospekt. Dukes went north. Ten nerve-racking minutes later they reconvened, as arranged, in front of a haberdashery on Nevsky Prospekt. There was no acknowledgement; it was an opportunity for each of them to determine if the other was being followed. Dukes had said he would stamp the snow from his boots if he felt they were safe to proceed. This he now did, before setting off once more at a brisk pace. Tom tailed him at a distance, his fingers closed around the revolver in his pocket, unsure of their destination.

He tried to remain alert, but his grief came at him in waves. He had walked this same route with Irina, idly strolling in the summer heat, stopping every so often to peer into a shop window, the scarlet trams rattling back and forth nearby.

He choked back a sob and felt the heat of anger rising in his belly. He didn’t fight to suppress it; he let it spread through him, into his chest, along his limbs, warming him.

It came to him quite suddenly what he would do and how he would do it.

It was a religious building of some kind, set well back from the street behind a high wall at the southern end of the Nevsky. Beyond the imposing entrance gate the trees rose tall and bare on either side of the pathway. Dukes cut left almost immediately into the trees, taking a well-trodden trail through the deep snow. It led to a cemetery deep in the wood, a bosky burial ground for the wealthy, sparsely populated with the dead. Large free-standing tombs were scattered around a frozen lake, like temples in some eighteenth-century garden.

The packed snow of the snaking pathways suggested that many others had visited in recent days, possibly paying a final tribute to their ancestors, it occurred to Tom, before fleeing the country for good. Right now, though, the two Englishmen found themselves alone. The purpose of their own pilgrimage was still no clearer to Tom, even when Dukes made for a tomb pushing four-square through a deep drift.

No larger than a garden shed, it was maybe twice as tall, its roof crowned with a Russian cross. The pale green stucco of its outer walls had crumbled in parts, revealing the bare stone blocks beneath. Its door was of solid wood and firmly locked.

Dukes was still struggling with an iron key when Tom joined him. The lock finally emitted a rasping groan and the door swung open on rusty hinges. The moment they were inside, Dukes shouldered it shut behind them.

The only illumination came from a small lunette above the door, and it was a few seconds before Tom’s eyes adjusted to the gloom, by which time Dukes was already on his knees before the altar. For a worrying moment it looked as though he was praying, but he was working away at one of the flagstones, prising it up with a pocket knife. Buried in the packed earth beneath was an old cigar box. It contained a wafer-thin package wrapped in waxed paper.

‘Here,’ said Dukes. ‘Take it with you.’

Tom had handled enough of Dukes’s coded intelligence reports in the past to know what it was.

‘Tell them I need more money – a lot more.’ Replacing the flagstone, Dukes got to his feet and stamped it down. ‘Deal directly with Leonard. I wouldn’t trust Bayliss with anything more than a cocktail shaker.’

‘You’re staying?’ asked Tom, incredulously.

‘It’s not over yet.’

‘But what about Zakharov?’

‘You think he’s the first to betray us?’

The weary fatalism of the statement grated. It suggested that the Zakharovs of the world were an unavoidable irritant to be endured, like mosquitoes, or people coughing in the theatre.

Tom removed his cap and pulled some banknotes from the lining. ‘It’s all I have left.’

Dukes riffled through the money, clearly delighted. ‘How much do you need?’ he asked.

‘I’m not sure.’

Dukes pocketed most of the cash and handed the rest back. ‘This should see you back to Helsinki.’

These weren’t the last words the two men exchanged. As they parted company outside, Tom asked, ‘How do you live like this?’

Dukes hesitated before replying. ‘I was here when the Revolution broke, when we turned the Tauride Palace into an arsenal. You see, I once believed in the New Jerusalem. Maybe I still do. But this isn’t it. This . . . this is Abaddon.’

He touched Tom lightly on the arm. ‘Tell Leonard from me that it’s not too late.’

‘For what?’

‘He’ll understand.’

As Tom watched the slight, anonymous figure shuffle off down the pathway, something told him that this would be his last ever glimpse of the man.

Abaddon, the place of punishment.

A fitting analogy, Tom reflected, his thoughts turning once more to Zakharov, the betrayer.

Chapter Two

Toulon, France. July 1935. Sixteen years later.

The porters were already in place, ranged along the platform like a guard of honour, when the train pulled into Toulon station. The heat was oppressive, and they fidgeted in their brass-buttoned tunics. A few of them crushed their cigarettes underfoot as the train shuddered to a halt and the carriage doors swung open.

Lucy was one of the last to descend. She had cut her hair short, and Tom might not even have recognized her had she not spotted him and waved.

Seeing her at a distance lent a new perspective. He realized, with a touch of sadness, that although she had lost none of her coltish grace she was no longer a girl. She had become a woman. It wasn’t just her new coiffure, or even her elegant organdie summer frock, it was the way she carried herself, the easy manner in which she proffered her hand to the guard who helped her down to the platform, the casual comment which set the fellow smiling.

Tom fought his way through the throng, arriving as her Morocco travelling bags were being loaded from the luggage car on to a trolley.

She might have changed, but she was still happy to launch herself at him and hug him tight, limpet-like, as they had always done. She smelled of roses.

‘Thank you,’ she said.

‘For what?’

She tilted her head up at him. ‘For the nice man at Victoria station who showed me to the first-class carriage, and the other nice man in Paris who showed me to my own sleeping compartment.’

‘An early birthday present. Don’t assume I’m setting a precedent.’

Releasing him, she looked around her. ‘Where’s Mr H?’

It was her name for Hector, his flat-coated retriever, his shadow for the past four years.

‘Missing.’

‘Missing?’

‘Since yesterday.’

‘Oh, Tom . . .’

‘I’m sure it’s nothing,’ he replied with as much non chalance as he could muster. ‘Maybe he needs a holiday too.’

But it wasn’t like Hector to go off for more than an hour or so, and only then to scrounge scraps from the customers at the bar in Le Rayol. Hector was a big coward at heart, although like all the best cowards he cloaked his fears in bold and boisterous behaviour.

‘It’s not the first time he’s done a disappearing act. I’m sure he’ll turn up as soon as he knows you’re here.’

Lucy looked unconvinced but was happy to play along if it spared them both the discomfort of any further discussion.

‘So, what do you think?’ she said brightly, flicking her fingers through her cropped hair and throwing in a theatrical little pout for effect.

‘I think your mother’s going to need a very stiff drink.’

‘That wasn’t the question.’

‘I think,’ Tom intoned with deliberation, ‘that you are more beautiful than ever.’

Lucy smiled. ‘Spoken like a true godfather.’

Tom’s car was parked out front in the shade of a tall palm. The porter set about loading the bags into the boot.

‘A new car,’ Lucy observed.

‘Not new, just different.’

‘It’s a lot smaller than the last.’

‘Ah, but this one doesn’t break down.’

‘Where’s the fun in that?’

She was referring to the previous summer and the day-trip with her family which had turned into a two-day-trip when the big Citroën had resolutely refused to start, stranding them as the sun was going down at a remote beach on the headland beyond Gigaro. There had been just enough food left in the picnic hamper to cobble together a simple supper and they had hunkered down for the night. Lucy’s half-brothers, George and Harry, had slept in the car, the rest of them under the stars around a driftwood fire, cocooned in Persian rugs. Leonard had embraced the setback with his usual sunny good humour, and even Venetia, who relished her creature comforts, had entered into the spirit of the occasion, leading them in a repertoire of Gilbert and Sullivan numbers, which had set Hector howling in protest. Remarkably, Leonard and Venetia had gone a whole evening without arguing, although they had bickered like a couple of old fishwives during the long and dusty march back to Gigaro the following morning.

‘Don’t worry,’ said Tom, ‘I’ve already planned another night at the same beach. It’s on the itinerary.’

‘Ahhh, the famous Thomas Nash itinerary.’

‘Would you have it any other way?’

‘Of course not,’ said Lucy, hugging him again. ‘I need someone to take command of my miserable existence.’

‘Oh dear, are the hardships of student life taking their toll on poor little Lucy?’

She pinched his arm and recoiled. ‘Well obviously you’re too old to remember, but Oxford’s not all honey and roses.’

‘Okay, what’s his name?’ asked Tom wearily.

Lucy looked convincingly aghast for all of a second before her face fell. ‘Hugo Atkinson . . . although I now have a whole bunch of other names for him.’

‘Didn’t he like your hair?’

‘This wasn’t done for him!’ she protested, a touch too vehemently.

Tom was suddenly aware of the porter regarding their little theatre with curiosity. He paid the man off handsomely and opened the passenger door for Lucy.

‘You can tell me all about the bounder over lunch, but I think I might have found just the thing to help you get over him.’

‘Oh God, please, not another Italian lawyer.’

‘Francesco, I admit, proved to be something of a disappointment.’

They both laughed at the memory of the disastrous dinner last summer. Two cocktails on the terrace at Les Roches had revealed Francesco to be a pompous and pugnacious bigot, and even before their entrées had arrived he’d been making eyes at one of the waiters.

In the ordinary course of events Tom would have driven directly from the station to the old port, where a stroll along the bustling waterfront would have been followed by lunch at the Brasserie Cronstadt. That was his customary routine when guests arrived on the late-morning sleeper from Paris. But he had others plans for Lucy, and they involved driving straight to Le Lavandou, skirting the hilltop town of Hyères before dropping down through the pine forests towards the coast.

They chatted lightly about the string of parties which had kept Lucy back in London, sparing her the long drive south through France with Leonard and her mother.

‘I can’t say I missed it. All those detours to cathedrals that Leonard insists on making, the lectures on the transition from Romanesque to Gothic architecture . . .’

‘Is that the real reason George and Harry can’t make it this year?’

‘No, Grandfather really is taking them to Portsmouth for Navy Week.’

‘And you weren’t tempted?’

‘I’d rather gnaw through my arm.’

Tom laughed. ‘Well, I’m sorry they won’t be here.’

‘I’m not. They’ve become insufferable lately.’

‘You mean big sister can’t boss them around any more?’

‘Exactly! The wilful little brutes.’

Le Lavandou, with its palm-fringed promenade and its port backed by a huddle of old buildings, still felt like a frontier town to Tom. Although he visited it often, it lay at the western limits of his ordinary beat and he rarely ventured beyond it. Whenever he did so, returning there was like returning home, even if home still lay a good few miles to the east along the twisting shoreline of the Côte des Maures.

The table was waiting for them under the awning at the Café du Centre, and Pascal appeared within moments of their arrival bearing a bottle of white Burgundy on ice. Nothing had been left to chance. The table, the wine, even the fish they would eat, all had been chosen in advance by Tom when he’d passed through earlier that morning. He wanted the build-up to the big surprise to be perfect.

Pascal was one of the few people in on the secret and he was obviously determined to play his part to perfection. Like a child sworn to silence, though, the burden proved almost too much to bear.

As soon as he had disappeared back inside, Lucy lit a cigarette and enquired, ‘What’s wrong with Pascal? He keeps looking at you in a funny way.’

‘Really?’

‘All weird and wide-eyed.’

‘Maybe it’s lack of sleep. Their new baby’s only a few weeks old.’

This seemed to satisfy her; besides, they had better things to discuss. It was almost six months since they’d last seen each other – during one of Tom’s rare visits to England – and on that occasion there’d been little opportunity to talk openly. In fact, there’d been little opportunity to talk at all, because Lucy’s great friend, Stella, had muscled in on their lunch at the Randolph Hotel. Like Lucy, Stella was a second-year Modern History undergraduate at St Hugh’s College. Unlike Lucy, she seemed to think this entitled her to hold forth at length on any subject that happened to pop into her head. And there was certainly no shortage of those: everything from the worrying rise of Fascism to the latest fashions in women’s shoes. In her defence, Stella was well informed and extremely amusing with it, but Tom could still recall the delightful silence of the long drive back to London from Oxford.

‘How’s the irrepressible Stella bearing up?’

‘Oh, dear,’ sighed Lucy. ‘Poor Stella . . .’

‘What? She’s developed lockjaw?’

‘Worse. She’s gone totally potty on an Irish labourer.’

‘You’re joking!’

Apparently not. St Hugh’s was in the process of putting up a new library, and the college had been crawling with brawny workmen for much of the year, one of whom had caught Stella’s eye.

‘Nothing’s happened,’ Lucy explained. ‘I mean, I’m not sure he even knows she exists, but she spent most of last term moping around her rooms like a sick cat. It’s all very Lady Chatterley and Mellors.’

‘What would you know about Lady Chatterley and Mellors? That’s a banned book.’

‘Which is precisely the reason there are so many copies doing the rounds at university.’

‘As the man who took an oath before God to lead you towards a life of exemplary purpose, I’m disappointed.’

‘As the man who had Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer lying around his house last summer, don’t be.’

‘Ah, it’s not banned in France.’

‘Well, it should be.’

‘Oh God, you didn’t read it, did you?’

‘Of course I did, the day you all went off to St Tropez.’

‘Ah yes . . .’ said Tom, remembering now, ‘the day you were struck down with a bad headache.’

‘A little trick I learnt from Mother.’ Lucy tapped the ash from her cigarette on to the cobbles at their feet. ‘How is she, by the way?’

‘Eager to see you.’

‘You really must learn to lie more convincingly.’

‘Well, I now know who to turn to for lessons, don’t I?’

They had been sparring partners for as long as he could remember, ever since Lucy was a small child. With the passage of time, the tickling and romping and mock fights of those early years had been replaced by a battle of wits and a war of words. Tom had always encouraged the playful cut-and-thrust of their relationship, if only because there had never been much of that sort of thing at home for Lucy. Venetia, for all her ‘modern ways’, was a mother cast in a traditional mould, somewhat cold and remote. As for Leonard, when not submerged in his work at the Foreign Office he leaned far more naturally towards his two sons than to the dead man’s daughter whom Venetia had brought with her into the marriage.

Tom no longer feared for Lucy’s emotional well-being. She had blossomed into something quite extraordinary: a beautiful, intelligent and amusing young woman who seemed genuinely oblivious of her manifest charms. And if he still sought out her company whenever he could, it was as much for his own benefit as hers, for what she somehow managed to bring out in him. As the conversation continued to coil effortlessly around them over lunch, she was, it occurred to him, one of the few true friends he had in the world.

When the coffee arrived they carried their cups with them to a wooden bench just across the cobbles from their table. Here, in the drowsy shade of the plane trees, they sat and watched in reverential silence as four old men, tanned to the colour of teak, played boules.

‘Let’s go for a wander,’ suggested Tom, the moment the match was over.

He led her across the road to the port. On one side of the central quay were moored colourful wooden fishing yawls, one of which had landed their lunch much earlier that day, while the rest of the world was still sleeping. Being a fanatical sailor, Lucy was far more interested in the array of yachts and dinghies bobbing on the gentle swell across the way. They came in all shapes and sizes – there was even an ostentatious gentle-man’s cabin launch amongst them – but her eye was drawn to one sailboat in particular.

‘Oh my goodness, look at that!’

‘What?’

‘That racing sloop.’

‘Yes, pleasing on the eye.’

‘I bet she flies.’

‘I’m not so sure,’ said Tom. ‘She looks like she’s sitting a little too low in the water.’

‘That’s to fool idiots like you. I’m telling you, she flies.’

‘Well, let’s find out, shall we?’

He leapt from the quayside on to the varnished fore-deck, turning in time to see Lucy’s look of incredulity give way to realization.

‘Don’t tell me, the royalties on your last book came through.’

Tom was on the point of revealing all – this was exactly as he had imagined it happening – but he held himself in check. ‘Something like that.’

Lucy kicked off her shoes and joined him on the foredeck, barely able to contain her excitement. ‘She’s not French. Where’s she from? Where did you find her? What’s she called?’

‘No . . . Sweden . . . Marseilles . . . Albatross.’

‘Albatross – I told you she flies! What is she, thirty feet?’

‘Twenty-eight.’

‘Her skinny lines make her look longer.’

Lucy dropped into the deep cockpit, running her hand along one of the benches before gripping the tiller and staring up at the tall mast. ‘Oh, Tom, you’re a lucky man.’

‘I thought we’d sail the rest of the way to Le Rayol.’

‘What about the car? My luggage?’

‘Pascal’s going to drive it over.’

She smiled, aware now that she’d been set up. ‘I’ll have to change my clothes first. I can hardly go to sea dressed like this.’

‘There’s a shirt and some shorts down below. No standing headroom in the cabin, I’m afraid, so you’ll have to crouch.’

The mainsail was already rigged, and while Lucy changed, Tom rigged the jib.

‘Good work,’ came a voice from behind him as he was finishing up. Lucy was barefoot and wearing an old cap tilted at a rakish angle.

‘Thanks, Skipper.’

Her face lit up. ‘Really?’

‘Take her away. There are winches for both halyards, so any half-decent sailor should be able to handle her solo, even in a blow.’

Her eyes narrowed at the challenge.

They slipped the lines and backed the sloop out between the pilings into the harbour. Tom made to paddle the stern around.

‘Stand down, bosun, if you know what’s good for you.’

Lucy raised the tall jib so that the wind brought the nose around and the boat began to make gentle headway.

‘So, tell me more about your antidote to Hugo Atkinson,’ she demanded.

‘Well, he’s American, and he’s a painter.’

‘A good one?’

‘Good enough for Yevgeny and Fanya to take him on.’

‘That sounds suspiciously like a no.’

‘He’s of the wilfully modern school. You know the sort of thing . . . a bowl of fruit can’t be allowed to actually look like a bowl of fruit, it has to look like it’s been hurled to the floor, trampled by a battalion of the Welsh Guards, scooped up with a shovel and dumped back on the table.’

Lucy laughed. ‘Well, obviously Yevgeny and Fanya see something you don’t.’

‘Large profits, I suspect.’

Yevgeny and Fanya Martynov were an eccentric couple, White Russian émigrés who ran a thriving Left Bank art gallery in Paris devoted to the avant garde. They had summered in Le Rayol for the past four years, following their purchase of a pseudo-Palladian villa up on the headland towards Le Canadel. They operated an open-house policy for artists of all kinds, and the steady stream of painters, sculptors and photographers passing through La Quercia was always a welcome source of entertainment.

‘They’ve put Walter in the cottage so that he can work in peace.’

‘Walter?’

‘He’s not as stuffy as he sounds, and he knows how to swing a tennis racquet.’

‘Have you played him?’

‘Four times now.’

‘Vital statistics?’

‘Won three, lost one.’

Lucy threw him a look.

‘Mid-twenties, although he looks older, probably because he’s on the portly side.’

‘Portly?’ said Lucy, unable to mask her disappointment.

‘Pleasingly so. Well-fed rather than fat. What else? He’s not tall, but you wouldn’t describe him as short . . . well, some might. And he still has most of his hair, which is dark and rather wiry.’

‘He sounds . . . intriguing.’

‘No he doesn’t, but he is. I’ve got to know him rather well over the past couple of weeks.’

Lucy brought the sloop about, falling in behind a forty-foot cruising ketch motoring towards the harbour mouth.

Beyond the breakwater, the wind piped up nicely, but Lucy seemed in no hurry to run up the mainsail. Her gaze was fixed on the ketch beating to windward at a fair lick, under full sail now.

‘I think that’s enough of a head start, don’t you?’

She cranked the winch, raising the mainsail.

The moment the ketch’s skipper saw them coming he began barking commands, not that it made any difference. The Albatross cut through the chop as if it didn’t exist, her big canvas sheets sucking every available ounce of energy out of the air. While the crew of the ketch scrambled about her topsides, trying to trim up properly, Lucy barely moved a muscle. When she finally did, it was only to offer a demure little salute to the skipper as she overhauled him.

‘Judging from his expression, I would say he hates you.’

‘It wasn’t me,’ grinned Lucy, her flushed face a picture of pure contentment. ‘The helm’s so balanced I could have tied off the tiller and taken a nap.’

They fell off, running dead before the wind to the eastward, making for Le Rayol. While Lucy put the sloop through its paces, getting to know its limits, Tom sat back and enjoyed the view.

There were any number of spots along the Riviera where the mountains collided with the sea, but for a short stretch east of Le Lavandou it seemed almost as if the two elements had struck some secret pact, Earth and Water conspiring together to create a place of wild, primitive beauty. The high hills backing the coast fell away sharply in a tumble of tree-shrouded spurs and valleys which were transformed on impact with the sea into a run of rocky headlands separated by looping bays. Dubbed the Côte des Maures – a reminder of a time when the Saracens had held sway over this small patch of France – the exoticism of the title seemed entirely appropriate. The beaches strung out along the shoreline, like pearls on a necklace, were of a sand so fine and white, the waters that washed them so unnaturally blue, that they might well have been transported here from some far-flung corner of the tropics.

‘Stand by to gybe!’ called Lucy.

‘Ready.’

‘Gybe ho!’

They both ducked the swinging boom as the stern moved through the wind, bringing them round on to a port tack run. Lucy steadied up the Albatross. ‘She feels like a big boat but responds like a small one. How’s that possible?’

It was a rhetorical question, and Tom smiled at her wonderment.

Only one thing was missing from the moment: Hector. He should have been there with them in the cockpit, or, as he often liked to do, standing steadfastly at the bow, snout into the wind like some canine figurehead.

Tom had spent the previous evening walking the twisting coast road either side of Le Rayol, checking the verges and ditches, sick with fear at what he might find. He pushed the memory from him, steering his thoughts towards a far more pleasing prospect: that Hector had finally found his way home, and that as they sailed into the cove below the villa he would come bounding out of the trees behind the boathouse on to the little crescent moon beach, barking delightedly.

It didn’t happen.

They tied up at the buoy where the rowboat was already tethered and waiting for them. The Scylla, Tom’s old knockabout dinghy, lay at her anchor nearby.

‘So,’ he asked, ‘what do you make of her?’

‘What do you think I make of her! She’s the closest thing to perfection I’ve ever helmed.’

‘That’s good, because she’s yours.’

Lucy stared, unsure if she’d heard him correctly.

‘Your twenty-first birthday present. A week early, I know, but I couldn’t wait.’

Lucy was speechless.

‘She comes with free transport to England . . . I might even sail her back myself. Should ruffle a few feathers down at the Lymington Yacht Club,’ he added with a smile.

Lucy didn’t smile. In fact, her face creased suddenly and tears filled her eyes.

‘Hey . . .’ Tom moved to take a seat beside her, slipping a tentative arm around her shoulders. ‘What’s the matter?’

She shook her head as if to say that she couldn’t explain. He thought perhaps he’d made a big error, wildly misjudging the appropriateness of such a gift.

‘I don’t understand,’ choked Lucy. ‘Why me?’

‘Because I love you, of course.’

This set her off again, worse than before, and it was a while before she composed herself enough to ask, ‘How can you say that so easily?’

She was wrong. He had only ever spoken those words to one other person, a long time ago.

‘Does Mother . . .?’

‘Don’t worry,’ said Tom. ‘She knows.’

‘But she doesn’t approve.’

‘She thinks I spoil you.’

Lucy wiped at the tears with the back of her hand. ‘She’s right, you do.’

‘Godfather’s prerogative. Besides, I don’t have anyone else to spoil.’

He hadn’t intended it to sound so self-pitying, and her response threw him.

‘What about your lady friend?’

‘My lady friend?’

‘The one who lives in Hyères.’ He glimpsed the familiar spark of mischief behind the watery sheen of her eyes. ‘Leonard told me about her.’

‘That’s not like him.’

‘He was defending you. Someone at dinner said he thought you were a homosexual.’

‘Oh?’

‘Leonard put him straight.’

‘So to speak.’

Lucy smiled weakly at the joke. ‘Do you buy your lady friend boats?’

‘She has other admirers for that sort of thing.’

Lucy looked at him askance. ‘You mean you share her?’

Tom hesitated. ‘That’s not how I think of it.’

‘How can you share her?’

‘Get to my age then see if you ask the same question.’

‘You’re only thirty-nine.’

‘It feels older than it sounds.’

It was a few moments before Lucy replied. ‘Well, I hope I’m still asking the same question when I’m thirty-nine.’

‘So do I,’ said Tom softly. ‘So do I.’

Lucy laid her head against his shoulder, sobbed a couple more times then said, ‘Thank you for my beautiful present.’

He kissed her on the forehead. ‘It’s my pleasure. Now pull yourself together, Captain – whatever will the crew think?’

They parted company just behind the boathouse, where the path bifurcated.

‘Are we seeing you later?’ Lucy asked. ‘Not tonight. You have house guests.’

‘Really? Who?’

‘I’m not sure you know them. They’re friends of your mother’s psychoanalyst.’

‘Oh God . . .’

‘They’re not so bad. I had them over for dinner last night. She speaks as much nonsense as the time allows her, and he perks up no end if you get him on to Phoenician pottery.’

‘Thanks for the tip,’ groaned Lucy.

‘Until tomorrow.’

Lucy set off up the steep pathway through the trees, making for the house that her parents rented every July. Standing proud on the promontory, just back from the bluff, it was so hemmed in on its three other sides by Tom’s land as to make it almost part of his property. With any luck, by the end of the summer it would officially become so. He was deep in negotiations with the owner, a retired thoracic surgeon from Avignon eager to convert his holiday home into hard currency which he planned to fritter away before he died; anything to prevent it falling into the hands of his two feckless sons.

He was a charming old boy, but he drove a hard bargain. He knew that the British pound went considerably further in France than it did back home, and he understood the notion that something could amount to more than the sum of its parts.

Tom might already own a substantial patch of the coastline directly east of Le Rayol, but the last remaining parcel at the heart of his kingdom must surely be a thorn in his proprietorial side, and therefore worth considerably more to him than the marketplace might suggest.

That was Docteur Manevy’s thinking, and Tom couldn’t fault it, or even begrudge the old fellow for it. If he’d learned anything during his five years in the country it was that no Frenchman could abide the idea of being taken for a ride. ‘Ne pas être dupe’ was the inviolable code by which they led their lives, and Tom had grown to embrace the theatre that accompanied most negotiations.

He would continue to play up his role as the impecunious author of travel books, Manevy would bleat on about the scandalously small government pension he received, and eventually they would arrive at an agreement satisfactory to both of them. That was the way of things. One had to remain patient.

As for the house itself, Venetia referred to the place affectionately as ‘the Art Nouveau eyesore’. Like the castle in Irene Iddesleigh it was ‘of a style of architecture seldom if ever attempted’: a clumpy, three-floored structure devoid of any obvious charm, and which the architect, for reasons known only to himself and his original client, had chosen to orientate facing inland, turning a dumb mask to the stunning sea-view. Tom’s own house – an imposing Art Deco villa verging on the ostentatious – dominated the other headland flanking the cove, and together they stood like two watch-towers guarding against a seaborne invasion.

A crease in the rising ground ran north from the cove, deepening as it went, bisecting Tom’s land from the water’s edge almost to the railway line. This was the route he now took after parting company with Lucy.

While most of the fifteen-acre plot was carpeted in cork oaks, pines and palms, the narrow gulley was a shady world bristling with ferns, hostas, petasites and other plants that favoured the dark and the damp. In summer, the ground was dry and firm underfoot, but for much of the year it was positively boggy with spring water. Le Rayol was known for its springs, a rare asset along this parched stretch of coast, and – miraculously, like the widow’s cruse – his well never ran dry. It stood at the centre of a deep dell near the head of the gulley, where the rocks rose sheer on three sides and the inter-locking branches of the trees overhead provided a welcome canopy against the sunlight.

‘Hector . . . Hector . . . Come on, boy . . .’

The words echoed back at him, hollow, futile.

Hector would often come here to cool off when the mercury was nudging ninety degrees, but he wasn’t here now.

The donkey engine and the water pump were housed in a wooden shed beside the well. Tom cranked the wheel, amazed, as always, when the faithful old Lister phut-phutted into life. The water in the big holding tank up top was running low. It would take a couple of hours to fill – more than enough time to complete his task.

He started in the northeast corner, right up by the railway cutting, where the ground vanished in a sheer drop of some thirty feet to the steel tracks below. From here he made his way back towards the sea, working methodically, taking each patch of land between the latticework of pathways in turn and searching it thoroughly, delving deep into the tangled underbrush.

Chapter Three

He signed for the cocktails and lay back on the sun lounger. As jobs went, he reflected, things didn’t get much better than this.

He cast his mind back over the other ones and concluded that things didn’t get any better than this. Talk about mixing business and pleasure: a summer break at a top hotel right on the beach, just one little chore to perform and then he’d be gone.

‘Why are you smiling?’

She had finished her swim and was towelling herself dry in the sunshine. She was in good condition for her age, although gravity had taken its inevitable toll on her breasts and buttocks.

‘Because I’m contented,’ he replied.

He spoke a formal French, far too formal, but it would have to do. It was the only shared language between them. He barely spoke a word of German, let alone Swiss German, and her Italian was a joke.

‘Is that for me?’ she asked in her guttural French, nodding at the drinks set on the table between their loungers.

‘Yes.’

‘You’re a bad boy.’

He was about to reply that she sounded like his mother, but checked himself just in time. She was, after all, close to his mother’s age; not so close as to repel him, but close enough for him to feel mildly squeamish at the prospect of seducing her.

‘I’m on holiday,’ he said. ‘And so are you.’

For the first time in their brief acquaintance, he used the familiar ‘tu’ instead of ‘vous’, and he could see that this didn’t go unnoticed by her.

She adjusted her bathing costume, brushed some imaginary sand from her thigh and lowered herself on to the lounger.

‘Well, if you insist . . .’ she purred coquettishly, following his lead and using the familiar pronoun.

He knew from their conversation on the terrace after dinner last night that her husband had been held back in Zurich on business, leaving her to travel on ahead alone. He could picture the husband rolling around with his secretary on some dishevelled bed, and he wondered if she suspected the same.

‘Did you contact your friend?’ she asked.

‘My friend?’

‘The painter in Cannes.’

‘Oh him . . . yes.’

He remembered now. Stuck with the cover story he’d already shared with a couple of the other hotel guests, he’d embellished it slightly for her benefit, adding a touch of glamour to impress. The painter in Cannes was a childhood friend from Rome who had recently found great success abroad, and was eager to show off his new house on the Cap d’Antibes.

‘Have you decided when you’re leaving?’

Not immediately the job was done; that was liable to arouse suspicion. No, he would brave it out for a day or two afterwards, as he usually did.

‘When is your husband arriving?’

‘Saturday.’

He glanced around him, but the only people within earshot were two sun-bronzed children, a brother and sister, playing beach quoits nearby, and they were far too absorbed in their game to be listening.

‘I was thinking Friday,’ he said.

There, it was done. He had made his intentions plain. It wasn’t the end of the world if she didn’t take the bait, but it would be much better if she did. It was always good to have an alibi up your sleeve.

She didn’t react at first; she just took a sip of her cocktail and stretched out on the lounger, closing her eyes.

‘I’ve never done this sort of thing before,’ she said quietly.

‘You haven’t done anything.’

She turned on to her side and looked at him. ‘No, but I want to.’

He saw the way the skin hung loose on her thighs and around her neck, and he wasn’t entirely lying when he said, ‘Knowing that is enough for me.’

‘Well, it’s not enough for me.’

Chapter Four

Tom was familiar with the sound. Lying in bed at night, the creak of the big old vine that coiled its way up the front of the villa would often carry through the open French windows into his room when the wind was up.

But there wasn’t any wind tonight, not a breath of it.

He rarely slept the sleep of the innocent, lost to the world, and he shrugged off his liminal state in an instant, alert now, ears straining.

Maybe he’d been mistaken. All he could hear was the beat of the waves on the rocks below the villa, the ocean’s blind purpose to make all things sea.

No. There it was again. And a faint rustle of leaves.

Someone was climbing the vine, and there was only one reason why they would be doing that: in order to reach the large terrace which served the master bedroom where he slept.

He cursed himself for his complacency. He hadn’t slept with his gun to hand for almost a year. The old Beretta 418 was locked away in a drawer in the study, a symbol of a time when his life had been ruled by fear and suspicion. He prided himself on having finally mastered that debilitating state of mind. As if in affirmation of this, a harmless explanation came to him quite suddenly, taking the edge off his building panic.

Barnaby.

Barnaby wasn’t due until tomorrow evening, but he was quite capable of changing his plans on a whim, especially if he’d landed himself in trouble while motoring down through France, which was quite probable. Trouble and Barnaby had always gone together, and Tom could picture him having to flee some tricky situation entirely of his own making. Turning up un announced in the middle of night and then pouncing on Tom while he slept was exactly the sort of infantile prank that would appeal to Barnaby’s sense of humour.

The moonlight flooding through the French windows and painting the wall beside the bed would allow Tom to see the shadow-play of anyone entering from the terrace. Well, he would turn the tables on Barnaby, waiting until the last moment before scaring the living daylights out of him.

Then again, maybe he was stretching the realms of possibility, even by the preposterous standards of his old friend. Maybe it wasn’t Barnaby, but a burglar. A small band of Spaniards, professional housebreakers from Barcelona, had passed this way two summers back. Some were still serving time in Toulon prison.

Whoever it was, the person had now cleared the stone balustrade and was creeping across the terrace. Their soft footfalls ceased, replaced by another sound. It was hard to make out, but it sounded like someone un screwing the cap of a bottle.

Tom exaggerated his breathing to convey the impression of someone deep in slumber, and moments later the visitor slipped silently into the bedroom.

He knew immediately that it wasn’t Barnaby, not unless he had shrunk by half a head since April. Everything about the shadow on the wall was wrong. Most worryingly, it moved with a professional stealth, confident, unhurried. It was definitely a man, and as he stole towards the bed it became clear that he was carrying something in his hand, not a weapon – not a gun or a knife or even a cudgel – but something else.

Face down on the mattress, his head turned to the wall, Tom knew he was at a serious disadvantage. The only thing in his favour was that the intruder seemed set on drawing closer, levelling the odds with every step, bringing himself within range.

It was the familiar, sweet-smelling odour that spurred Tom into action. He exploded from the mattress, twisting and hurling himself at the figure looming beside the bed. Caught off guard, the man was sent crashing to the floor with Tom on top of him, gripping his wrists.

Stay close in, but keep his hands where you can see them. Then finish him off.

He drove his forehead into the man’s face. Twice. He was going for a third when the man bellowed and twisted away, slipping Tom’s clutches, not big, but surprisingly strong, and with the natural agility of youth on his side. Tom was after him in an instant. He wasn’t expecting the leg to lash out, catching him in the midriff, upending him.